-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

PLC Battery Low Warning Solution: Replacement Procedures

As a systems integrator who has lived through the Friday night red “BATT” light more times than I care to admit, I treat a PLC battery low warning as a gift. It’s an early, non‑critical alarm that buys you time to replace a consumable before it snowballs into lost programs, scrambled clocks, and weekend downtime. This article explains what the battery actually does, how to interpret the warning, how to plan and execute a safe replacement, how to verify the result, and how to set a maintenance rhythm that keeps your controls calm and predictable.

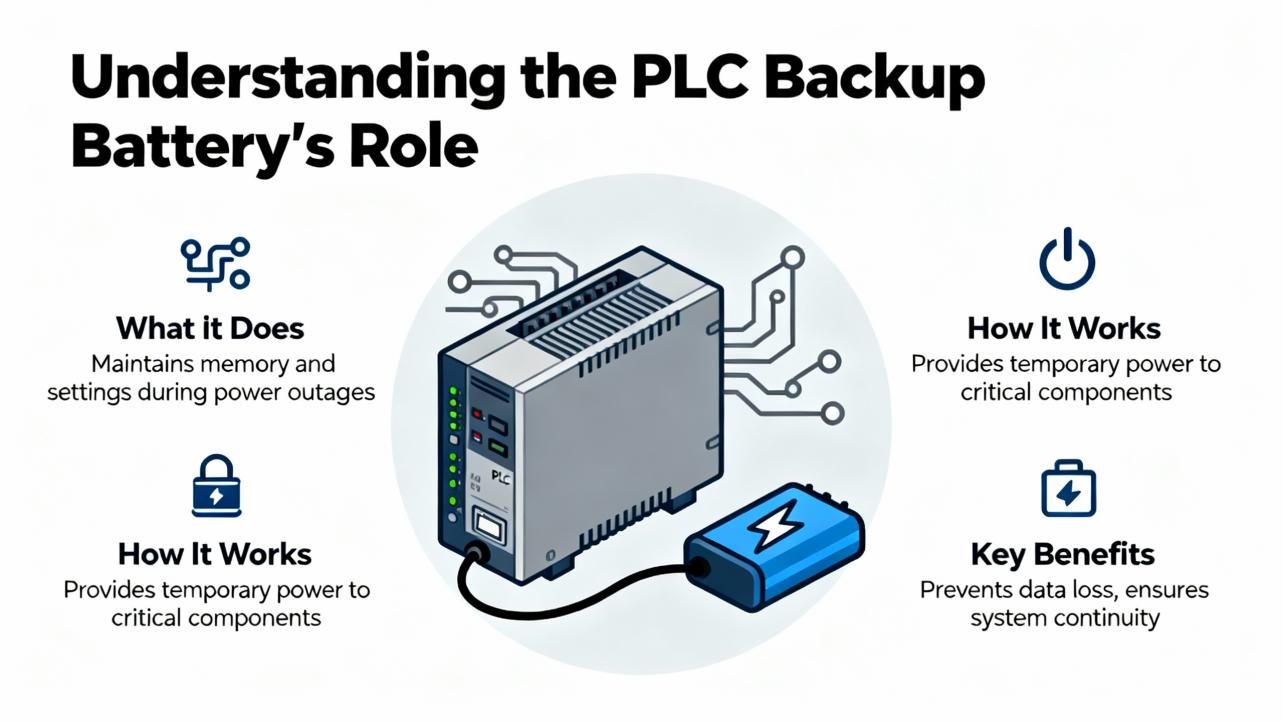

What the PLC Backup Battery Really Does

A PLC’s backup battery keeps volatile RAM alive when the main power is off so logic, configuration, setpoints, and the real‑time clock survive outages. That’s the entire mission. The moment external power is restored, the CPU stops sipping from the battery. Modern controllers often blend non‑volatile memory with RAM, but even then, RAM is still used for retentive tags and runtime data. When the battery is dead and power is lost, volatile content is at risk. Both Automation Forum and PDFSupply emphasize this point, noting that the controller can run perfectly with a dead battery while powered, but once power drops you can lose programs and data retained in RAM.

In mainstream PLCs, the battery chemistry is typically Lithium‑Thionyl Chloride, chosen for very low self‑discharge and long life in low‑current standby. Common voltages are 3.0 VDC and 3.6 VDC cells or packs. Capacitor “battery” assemblies also exist; they’re not batteries in a strict sense, but they can hold a charge long enough to ride through short power gaps.

Battery Options: Pros, Cons, and Practical Differences

Different facilities lean into different backup strategies based on outage patterns, safety rules, and maintenance culture. Distilling what I’ve seen across food, metals, and water/wastewater plants:

| Option | Typical Use | Strengths | Limitations | Service Life Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium backup battery (3.0 or 3.6 V) | Long‑term RAM retention | Long shelf life, stable under low current, simple to replace | Requires replacement cadence; primary lithium is not rechargeable | Commonly 2–5 years; replace proactively every 2–3 years (HESCO, Automation Forum, PDFSupply) |

| Capacitor memory backup | Short outages, brownout ride‑through | No battery to stock; abuse‑tolerant; fast recharge | Holds memory for hours to a few days; not for extended shutdowns | Often up to roughly 3 days of retention (Automation Forum) |

| UPS on control power | Whole‑cabinet ride‑through | Protects PLC, comms, and I/O; reduces brownouts | Batteries to maintain; adds cost and service | Cycle per UPS specs; integrate into PM program (GES Repair) |

If your plant power is stable but you perform periodic lockouts, lithium is simple and dependable. If your lines see frequent, short sags, capacitor‑based retention or a small UPS improves resilience. A blended approach is common: keep the PLC’s lithium battery healthy and use a UPS to mute nuisance drops.

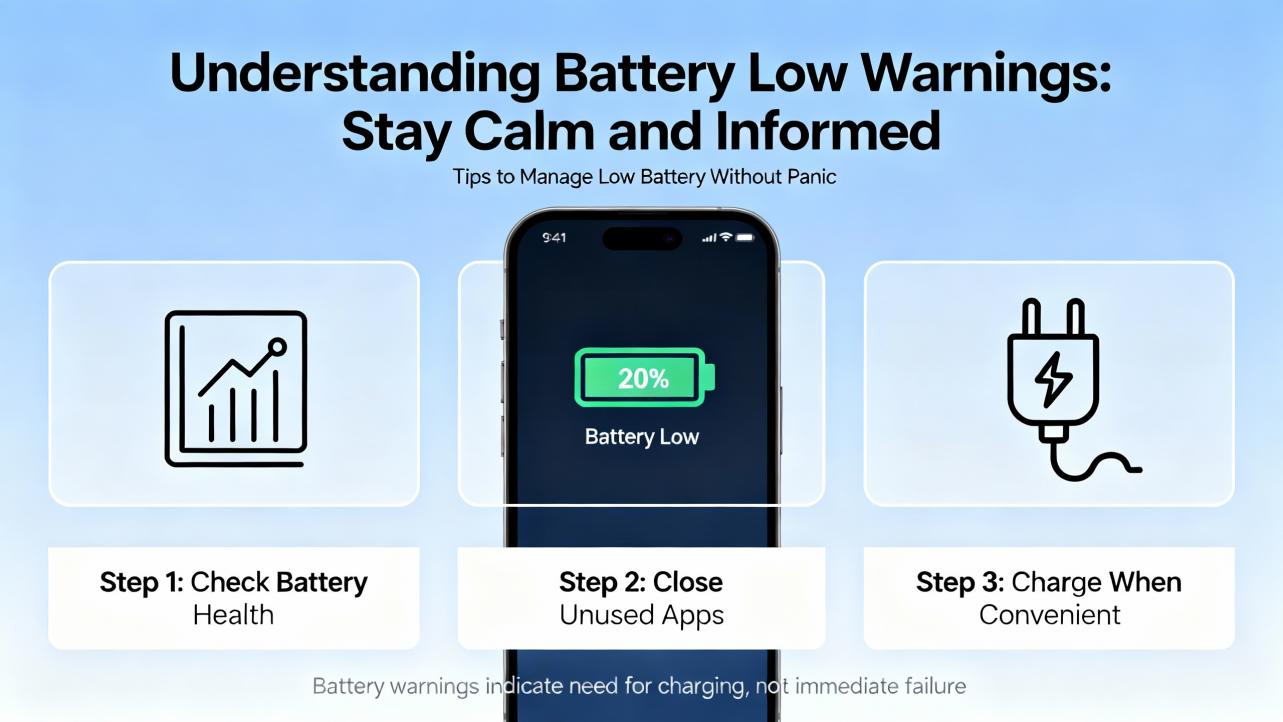

Interpreting a Battery Low Warning Without Panic

A battery low indication is usually non‑critical, flagged by the CPU’s BATT/BAT LED or a diagnostic minor fault. PDFSupply notes that a healthy battery leaves this LED off; yellow, red, or flicker means low voltage at or below the model’s threshold. Automation Forum adds that on some Allen‑Bradley PLC‑5 units with a 3.0 V cell, the trigger range is often around 2.0–2.5 VDC and may imply limited days of retention remaining. The exact threshold varies by vendor and model, but the message is consistent: plan a replacement soon.

A low battery should not, by itself, stop the process. It is designed to warn before data is at risk. If you see both a low battery and unrelated CPU error LEDs, follow a normal triage. Control.com reminds us that LED patterns convey distinct states; read the vendor’s blink codes and verify the controller mode, forces, and comms before assuming the battery is the only issue.

Typical Battery Life—and Why It Shrinks on Hard‑Used Lines

Most lithium assemblies serve for 2–5 years. HESCO and Automation Forum recommend replacing every 2–3 years as a best practice. Frequent power cycles, elevated temperatures, long power‑off periods, and aging hardware shorten life. I’ve seen older SLC 500 and PLC‑5 processors in high‑cycle plants need annual replacement because repeated outages pull the battery into service constantly. In continuous‑run systems, try not to exceed three years even if the LED looks happy; chemistry ages silently.

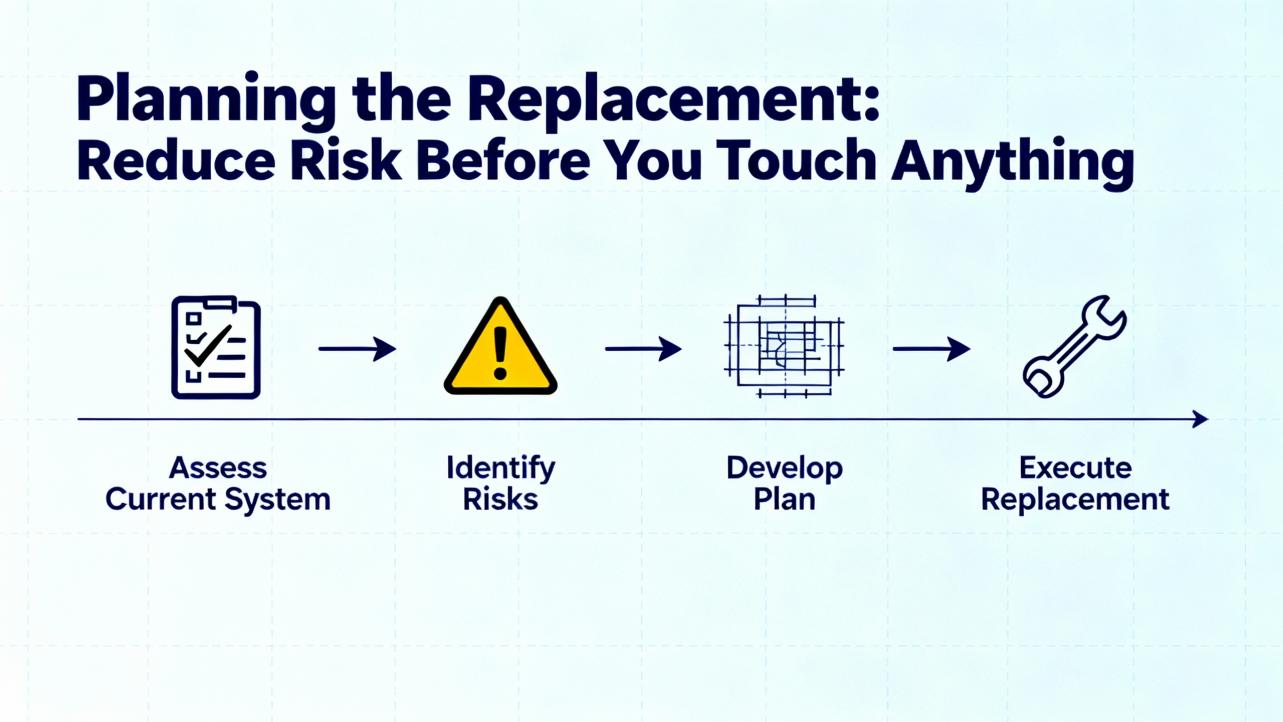

Planning the Replacement: Reduce Risk Before You Touch Anything

The single biggest mistake with PLC batteries is powering down to change them on a system with RAM‑resident logic. Don’t do that unless the manual explicitly says it’s safe. The low‑risk plan is replacing with the controller powered so the battery swap doesn’t drop RAM. Where operations require power‑off maintenance for access or safety, take extra steps: save and verify the program, confirm non‑volatile storage if applicable, and make sure your team knows how to restore the application if needed.

I structure each job the same way. First, identify the exact part: voltage (3.0 vs 3.6 V), connector style, length, and capacity. Second, make a current backup and store it in your versioned repository. HESCO recommends automated backups across many systems; Rockwell users often rely on AssetCentre for this. Third, schedule work during a planned window with the right PPE and ESD precautions. Fourth, bring two new, in‑date batteries from a reliable vendor so you can swap again if the first shows up marginal.

Step‑By‑Step: Power‑On Replacement Procedure

The safest method to preserve RAM is to keep the controller powered throughout the swap. This is the approach recommended by Automation Forum and aligns with what I do on most platforms.

Begin by confirming that the CPU is in RUN or the appropriate non‑Stop mode required by your process and that you are authorized to open the panel. Verify that the replacement battery matches the original specification. If I am unsure, I consult the platform manual or a known‑good spare list rather than “make it fit” with a look‑alike part.

Open the CPU face or swing the module if required to reveal the battery location. Many processors secure the pack with a small tab or a simple keyed connector; take note of routing. With the controller still powered, gently release the old battery from its clip or unplug the connector, taking care not to short the terminals. The CPU should continue to run on external power and should not drop memory during the seconds of disconnection.

Immediately connect the new battery, matching polarity and alignment. Tug lightly to confirm the latch is engaged and route the lead so it does not pinch when closing the door. Close the CPU cover, confirm that the battery warning LED clears within the expected delay, and then record the change in your maintenance log with the date, part number, and technician initials. If the LED does not clear, proceed to the verification section below.

Step‑By‑Step: Power‑Off Replacement With Guardrails

Some OEMs, safety rules, or enclosure layouts force a power‑off. In that case, preparation is your risk reducer. Start by uploading the active program and comparing it to the master copy. If you’re not a hundred percent confident the RAM image matches your archive, make a fresh backup. If the platform stores logic in non‑volatile memory automatically, verify that status online or in hardware configuration.

Shut down per lockout/tagout, replace the battery, and restore power. Watch the CPU indicators and the HMI on boot. If the PLC comes up with a memory fault or a default program, load the archive you just made. This is also the moment to check the real‑time clock and any retentive data that matters for your process, like running totals or quality counters.

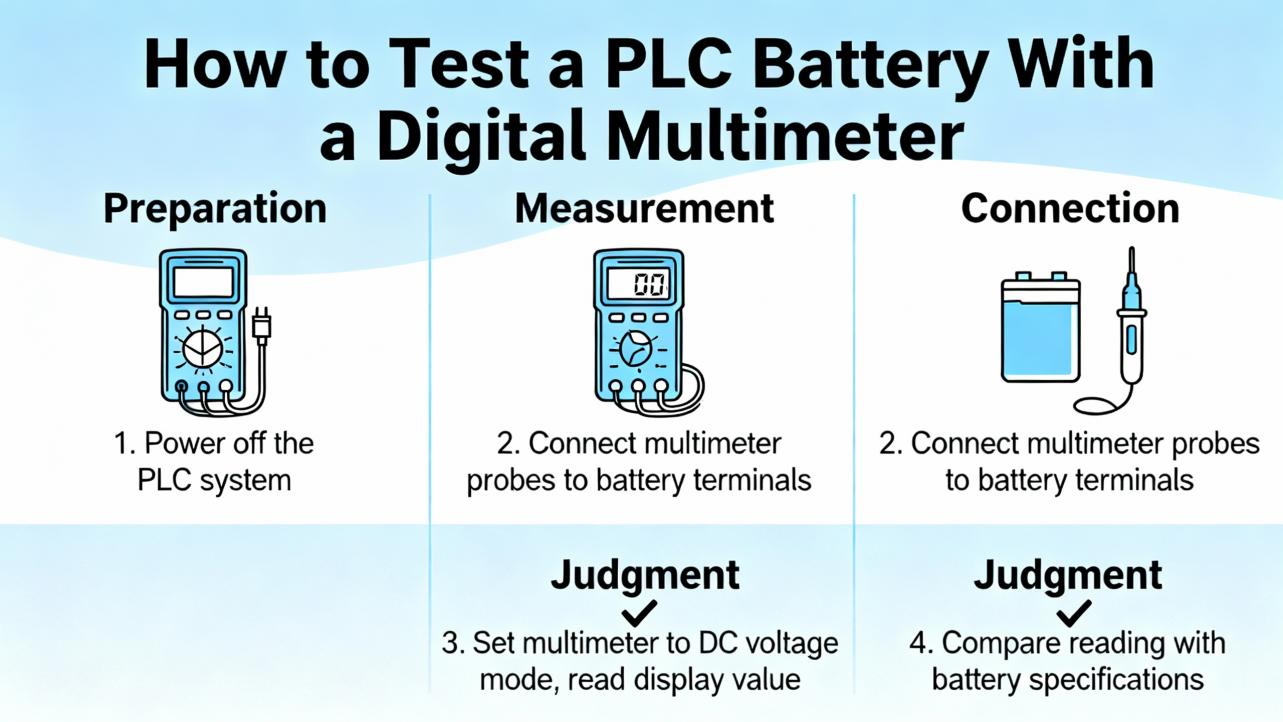

How to Test a PLC Battery With a Digital Multimeter

I don’t replace batteries blind when I can measure them, especially in distributed racks where LED state is hard to see. A simple DC voltage test answers most questions. PDFSupply outlines a straightforward setup: black lead to COM, red to the VΩmA jack, and the dial set to DCV. Choose a range above the rated voltage.

Measure across the battery terminals with correct polarity. Compare your reading to the nominal rating and the replacement thresholds.

| Nominal Voltage | Healthy Reading | Low/Replace Soon | Replace Immediately |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.0 V lithium | At or above 3.0 V | Roughly 2.0–2.5 V (low LED often active) | Below about 2.0 V |

| 3.6 V lithium | Around 3.6–3.7 V | Roughly 2.4–2.9 V (low LED often active) | Below about 2.4 V |

These bands reflect guidance compiled by Automation Forum and PDFSupply and match what I see in the field. Models vary, so confirm with your manual if you need precision beyond a go/no‑go bench test.

If you remove a battery to test it and find signs of leakage, corrosion, bulging, or damaged terminals, stop testing and dispose of it safely. Do not reinstall a compromised cell even if voltage looks passable.

Vendor‑Specific Notes That Save Time

Allen‑Bradley Logix controllers expose a minor fault bit for a battery condition, which is useful for programmatic alarms. The MrPLC community documents a GSV instruction reading the FaultLog’s MinorFaultBits into a DINT, where bit 10 indicates a battery‑related minor fault on certain models. I map that bit to a visible HMI alarm and add it to our historian so intermittent, short‑lived events are captured for maintenance planning. Always verify bit positions against current Rockwell documentation for your controller and firmware.

Siemens S7‑300 is a common example where a 3.0 V lithium pack around 950 mAh is used for memory retention; stick to the specified pack format and connector rather than improvising. FANUC and some CNC controls use multi‑battery assemblies with specific procedures; the manufacturer’s manual takes precedence there, because the order of replacement sometimes matters to prevent data loss.

After‑Replacement Verification: Close the Loop

A clean replacement ends with verification. A stubborn BATT LED often points to a connector that is not fully seated, the wrong battery type, or a depleted spare that sat too long on a shelf. Reseat the connector and confirm part numbers first. Check CPU diagnostics for explicit battery status words; many platforms expose the measured internal battery voltage. If everything looks correct but the LED stays on, measure the new battery at the connector to rule out a wiring break.

Confirm that the PLC retained the user program and retentive data across a controlled power cycle if your process allows. Set or validate the real‑time clock and restore any counters that do not persist by design. Finally, label the battery with an installation date and log the change in your CMMS or maintenance log. I also like to make the battery age visible on the HMI using a simple “months since replacement” tag if the platform supports it.

Care, Storage, and Buying Tips

A battery is a commodity until you buy the wrong one. Stick to the correct voltage, connector, and mechanical form factor for your CPU. Consider capacity where variants exist; higher mAh extends retention under long outages but cannot fix frequent power cycling. Buy from reputable suppliers to avoid old stock. Check packaging date codes and store spares in a cool, dry area away from heat sources; do not attempt to recharge primary lithium cells.

Match chemistries deliberately. If your platform specifies Lithium‑Thionyl Chloride, do not substitute a different lithium chemistry without vendor approval. For multi‑rack systems, unify part numbers to simplify kitting. Where budget allows, standardize across your installed base to reduce spares complexity.

If your lines run remote or lightly staffed, add a software alarm and consider remote alerting through your SCADA. HESCO notes that facilities benefit from a documented backup and battery policy; I’ve found a quarterly auto‑backup and a two‑year battery replacement timer to be a strong baseline.

Preventive Maintenance Rhythm That Works

The best programs are boring and predictable. I recommend logging a quick visual LED check during routine panel inspections because the BATT indicator is often hidden inside cabinets, as Automation Forum points out. Replace lithium PLC batteries every 2–3 years as a rule, sooner if your line is power‑cycled daily. For legacy platforms that are sensitive to supply sags, consider a small UPS on the PLC power rail; GES Repair highlights how brownouts and surges shorten life and corrupt memory.

Backups deserve their own cadence. Save and verify controller programs at least quarterly and after every significant change. If you manage dozens of controllers, an automated solution pays for itself the first time a CPU loses RAM.

To align expectations, this rule of thumb is reasonable across mixed fleets:

| Platform/Usage | Suggested Cadence | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Modern PLCs, stable power | Replace every 2–3 years | Verify during annual inspections |

| Legacy AB SLC 500/PLC‑5 with frequent power cycles | Replace annually | Older hardware and cycling drain faster (Automation Forum) |

| Continuous‑run systems rarely powered down | Do not exceed 3 years | Chemistry ages even if LED stays off |

Safety and Disposal That Keep You Out of Trouble

Treat small batteries with big respect. Wear appropriate PPE, avoid shorting terminals, and keep metal tools clear of battery contacts. Follow lockout/tagout whenever you de‑energize equipment for access.

Dispose of lithium cells per local rules. Automation Forum notes that leaking or damaged lithium batteries should be isolated; if you encounter a compromised cell, place it in a plastic bag, and per their guidance, double‑bagging in heat‑sealed polyethylene with a neutralizing agent such as calcium carbonate is one accepted practice for containment before disposal. Coordinate with your environmental health and safety team and your recycler, because local requirements vary.

Why This Matters to Uptime

Battery low warnings rarely cause immediate downtime. Most PLC problems trace back to I/O, wiring, and power, as both Do Supply and GES Repair observe. But ignoring a low battery converts a manageable task into a recovery event that forces you to reload programs, reset clocks, and revalidate interlocks under pressure. Replacing the battery on your terms—while the CPU is powered, backed up, and under your control—turns a blinking light into a non‑event.

Troubleshooting Stubborn Battery Alarms

Sometimes you replace the battery and the light stays on. The simplest explanation is usually correct: wrong battery, dead spare, or connector not fully seated. A less common cause is that the CPU latches the warning until a reset; check the manual. Certain CNC/NC controls differentiate between “warning” and “alarm” thresholds; for example, an NC might allow operation with a warning but block starts when the level crosses the alarm threshold. Scribd‑archived documentation describes this warn‑versus‑alarm behavior and reminds us that data integrity is not guaranteed if you shut down with an active alarm. If you are using an AB Logix controller, monitor the FaultLog minor fault bit to confirm the system’s internal view and to catch intermittent dips that clear by the time you look.

If the alarm persists across known‑good parts and reseating, measure the voltage at the CPU end of the battery lead to confirm the harness and board connection. I’ve also seen third‑party packs where the polarity inside the connector shell was reversed relative to OEM; those look fine and fail quietly. When in doubt, consult the vendor’s parts list and documentation rather than force a “compatible” solution.

A Realistic Replacement Walkthrough

Here’s what a disciplined swap looks like on a live production line. The maintenance tech acknowledges the low battery work order, verifies the exact part number, and pulls two spares from the climate‑controlled cabinet. Before opening the panel, they upload the program and confirm it matches the master archive. With the line in a safe state, they open the CPU door, note the battery routing, and unplug the connector with the controller still powered. A new pack goes in immediately, the connector clicks home, and the lead is tucked along the original path. The BATT light fades after a short delay. The tech labels the pack with today’s date, closes the panel, and updates the CMMS work order with the serial number and a note that the next replacement is due in two years. Back in the control room, the HMI alarm clears and the historian shows the change. It’s quiet, quick, and predictable.

Takeaway

A PLC battery low warning is a solvable maintenance task, not a crisis. Replace the battery with the CPU powered whenever possible, verify program backups before you start, and confirm the result afterward. Choose the correct chemistry and connector, store fresh spares, and adopt a two‑to‑three‑year replacement cadence tuned to your plant’s power habits. Use controller diagnostics—including the battery minor fault bit where available—to generate clear alarms and maintenance logs. These practices are drawn from field experience and echoed by sources such as Automation Forum, HESCO, Control.com, Do Supply, PDFSupply, and MrPLC. They turn a red light into a routine job you can schedule, execute, and forget.

FAQ

What happens if I ignore a low battery warning? Nothing may happen right away, but if external power is lost with a weak battery, the PLC can lose programs, retentive data, and the real‑time clock. You will be forced to reload and revalidate under time pressure. Sources like PDFSupply and Automation Forum stress replacing before you hit that point.

Can I replace the battery with the PLC powered? Yes, and that is the preferred method for most platforms because it preserves RAM. Keep the controller powered, remove the old pack, and install the new one quickly and carefully. Always verify the procedure in your controller’s manual.

How often should I replace PLC batteries? A practical baseline is every 2–3 years for lithium packs, adjusted for your outage pattern and environment. Some older platforms that see frequent power cycling benefit from annual replacement. Do not stretch beyond three years on continuous‑run systems even if the LED is off.

How do I know I bought the right battery? Match the voltage, connector, and mechanical format listed in the controller manual. Lithium‑Thionyl Chloride is the common chemistry. Avoid generic substitutions unless the vendor qualifies them. Check date codes and buy from reputable suppliers to avoid aged stock.

What if the battery LED stays on after replacement? Confirm the connector is fully seated, the polarity is correct, and the new battery’s voltage is healthy. Some controllers latch the warning until a reset. If in doubt, measure voltage at the CPU end, check diagnostics, and consult the manual. On AB Logix, you can also inspect the battery minor fault bit with a GSV instruction, as discussed by MrPLC.

Is there a way to alarm battery status in software? Yes. Many controllers expose battery status in diagnostics. On AB Logix, read FaultLog MinorFaultBits and map the battery bit to an HMI alarm. For other vendors, review the controller’s status registers. Logging these events makes maintenance proactive rather than reactive.

References

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357857924_Control_and_Monitoring_of_Battery_Energy_Storage_System_Using_PLC

- https://www.plctalk.net/forums/threads/plc-low-battery-alarm.127053/

- https://blog.hesconet.com/rockwell-automation-plc-troubleshooting-common-problems-and-solutions

- https://automationforum.co/step-by-step-plc-battery-replacement-and-maintenance-procedure/

- https://gesrepair.com/programmable-logic-controller-failure/

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/troubleshooting-battery-module-anomalies-case-study-bms-diagnostics-rbc3c

- https://info.panelshop.com/blog/troubleshooting-your-plc

- https://www.pesquality.com/blog/plc-5-troubleshooting-help

- https://blog.acsindustrial.com/industrial-electronic-repairs/tips-troubleshooting-troublesome-plcs/

- https://control.com/technical-articles/troubleshooting-plcs-recognizing-visual-status-indicators-and-leds/

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment