-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 21500 TDXnet Transient

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

PLC Program Memory Error: Recovery and Backup Strategies

When a controller throws a program memory error at 2:00 AM, nobody in the plant is talking about flash sectors or DM areas. They are talking about trucks waiting at the dock, a furnace that cannot cool down, or a filling line that has just gone silent. That is why, as a systems integrator, I treat PLC program memory not as an abstract technical detail but as a critical asset that has to survive power problems, noisy environments, firmware updates, and the occasional human mistake.

This article walks through how PLC program memory works, why it fails, and how to recover safely when it does. It then lays out practical backup and prevention strategies you can actually sustain on a busy plant floor. The guidance draws on field experience and on recommendations from sources such as DigiKey, major maintenance guides, and secure PLC coding initiatives backed by the ISA Global Cybersecurity Alliance.

What A PLC Program Memory Error Really Means

A PLC is a rugged industrial computer with a CPU, memory, and I/O, built to run your logic in real time. Under the hood, it typically uses two main classes of memory. Non‑volatile memory, such as NAND flash or EEPROM, holds the user program, configuration, and initial values even when power is off. Volatile RAM holds working data such as registers, holding areas, counters, timers, and real‑time process values. RAM is often kept alive during power loss by a backup battery.

A “program memory error” can mean several different things in practice. It can indicate corruption in non‑volatile memory so that the PLC can no longer load a valid program at startup. It can be a loss of volatile data because the backup battery failed or was swapped incorrectly. It can be an integrity problem where program instructions or data areas are altered by interference or an unexpected shutdown. Or it can be a simple resource problem: the compiled block is too large for the CPU’s available memory.

DigiKey notes that many PLCs can store the user program, setup parameters, data registers, comment data, and even the entire DM area in non‑volatile memory as initial values for recovery. At runtime, a battery‑backed RAM image holds the current values for holding areas, counters, and data memory. Power interruptions or low battery affect the RAM view, while flash or EEPROM issues affect the stored reference copy.

When a PLC reports a memory error, you need to quickly determine whether you have lost the program itself, lost retentive data, or simply hit a size limit.

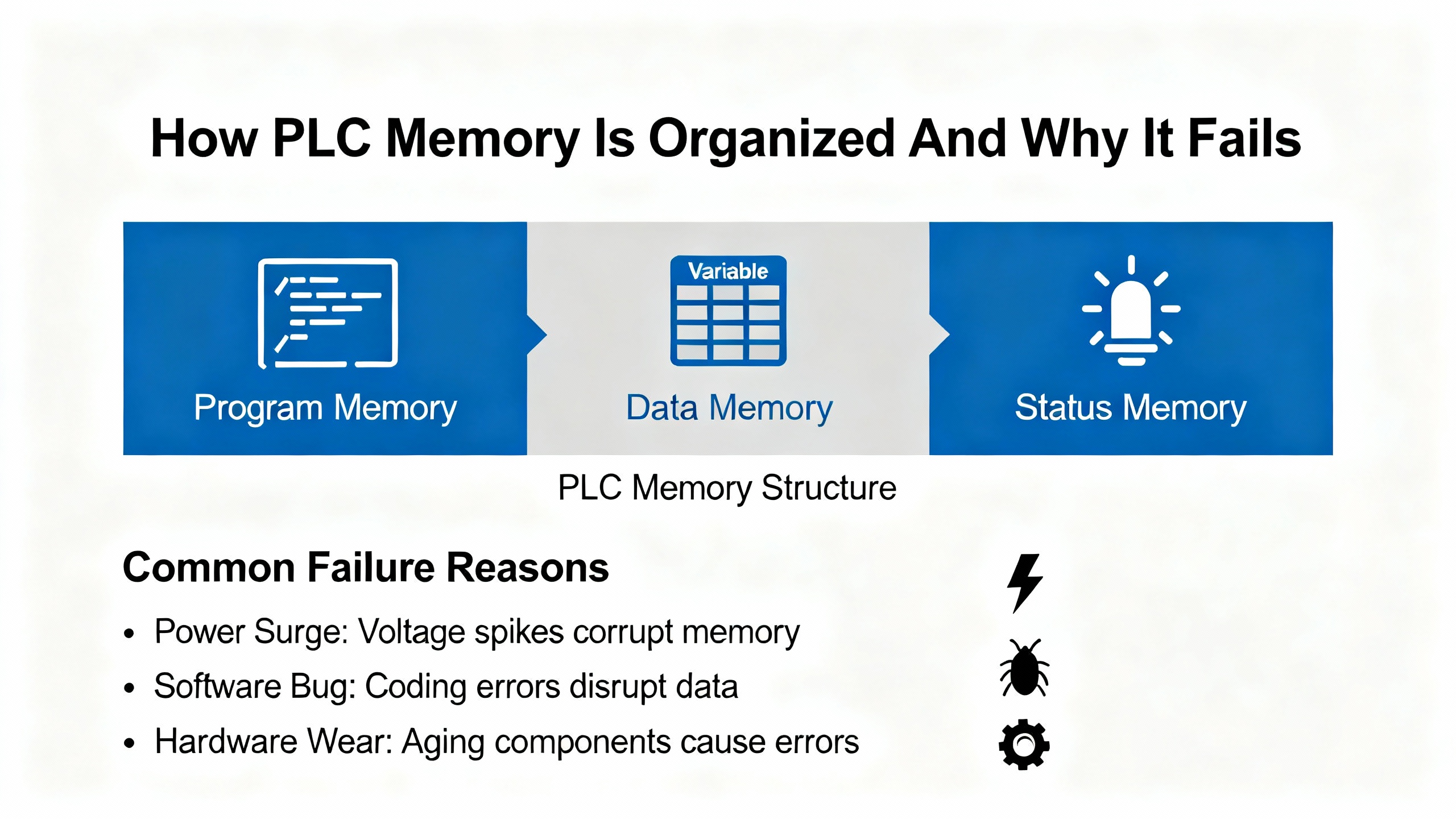

How PLC Memory Is Organized And Why It Fails

Most industrial PLCs use a layered memory architecture. The program load or user memory in flash or EEPROM stores the compiled blocks. Work memory (RAM) holds the copy being executed and the dynamic data. Separate retentive areas, often the holding area and portions of the DM area, are preserved across power cycles using battery power.

DigiKey explains that battery‑backed RAM typically maintains the holding area, DM area, and counter values, and in some architectures also keeps power to the RAM that stores the execution sequence pulled from non‑volatile memory. The same battery usually powers the real‑time clock, which is essential for timestamps and event logs.

This architecture is robust, but it has weak points.

Non‑volatile flash and EEPROM can be corrupted if power is interrupted while a read, write, or erase operation is in progress. A partial or failed write can damage not only the new data but sometimes neighboring blocks as well. Frequent write cycles, such as logging or rapid program changes, wear cells over years of use.

Battery‑backed RAM depends on that small battery and on good power discipline. If power is removed for long enough with no battery, or if the battery voltage drops too far, volatile data is lost. DigiKey notes that many PLCs provide self‑diagnostics and battery‑low indicators, but these warnings can be buried in diagnostic lists or missed on a crowded panel.

Environmental and electrical factors matter as much as firmware design. Articles from DoSupply and PLC technician training providers emphasize that EMI and RFI from large motors, welders, lightning, or handheld transmitters can inject noise that leads to memory corruption, particularly if grounding is poor. High temperatures, dust, and humidity accelerate component aging. Frequent power outages, brownouts, or noisy power supplies further stress both flash and RAM.

In other words, program memory errors rarely appear in isolation. They are usually the tip of an iceberg of power, grounding, and environmental issues that has been growing for months or years.

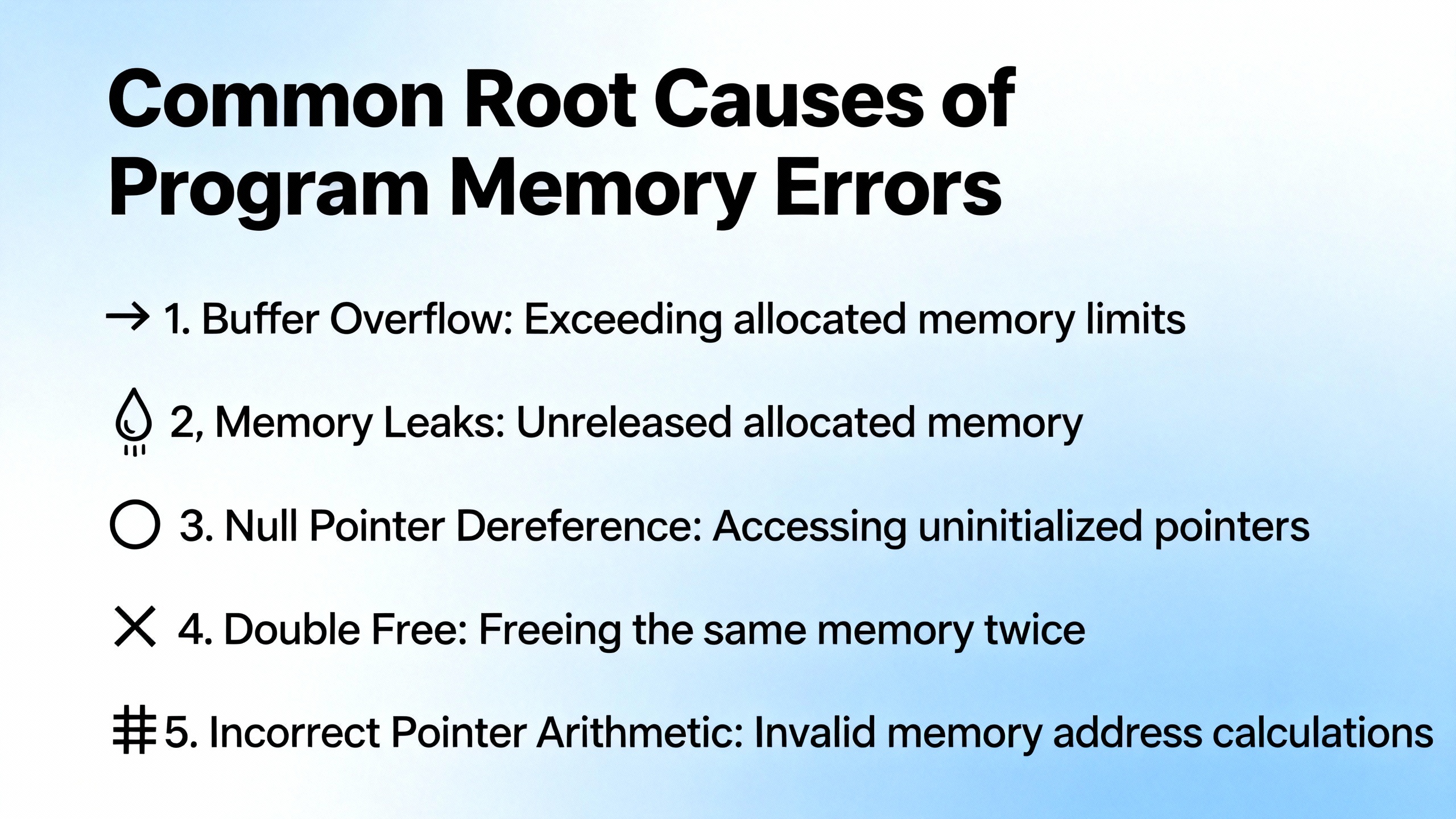

Common Root Causes Of Program Memory Errors

Across plants and vendors, a few patterns show up repeatedly when you dig into program memory incidents.

Electrical supply problems are at the top of the list. Power surges, fast voltage fluctuations, and short circuits can damage internal components or disrupt memory operations. Guides on common PLC faults describe how blackouts, grid failures, loose connections, and deteriorated cables cause data loss and boot failures. Without surge protection, clean power, and a stable supply, even the best‑designed controller is at risk.

Environmental stress is the quiet killer. PLC repair articles point to extreme temperature, humidity, dust, and corrosive substances as frequent causes of hardware degradation. Overheating, clogged filters, and dirty control panels slowly push components out of spec until something gives, often in the most complex part of the system: memory.

Software and programming issues are another major contributor. Programming errors, software corruption, or incompatible firmware can trigger memory faults or expose borderline conditions. Troubleshooting guides emphasize checking the logic for errors, validating data types, and using built‑in debugging tools to catch issues in a safe or simulated environment before deploying changes. Rushed online edits on a live plant are a common way to create inconsistent states in non‑volatile memory.

Electromagnetic interference plays a larger role than many teams realize. EMI or RFI from nearby machines can cause erratic readings, aborted memory operations, and sporadic communication failures. PLC troubleshooting resources describe ground loops, poor shielding, and mixed routing of high‑current and low‑level signal cables as repeat offenders.

Battery and retention issues are a distinct category. According to DigiKey, frequent power outages or long periods with the system powered off shorten battery life, especially at temperatures above about 77°F. When the battery becomes weak, holding areas and DM values can be lost between outages. If the battery is replaced incorrectly, for example leaving the PLC without a battery long enough for RAM to drop out, program and data retention can be compromised even if the flash copy is healthy.

Resource exhaustion is becoming more common as systems evolve. A Siemens forum example describes a block that previously ran on a PLC now triggering a “compiled program block is too large for the current PLC type” warning and being rejected, even though the same program still runs on an identical PLC elsewhere. That kind of error suggests subtle memory limits or degraded EPROM modules. On other platforms, similar issues show up as “out of memory” errors, extended scan times, or failures to download.

Finally, security and integrity issues cannot be ignored. The Top 20 Secure PLC Coding Practices and OT cybersecurity guides describe how unauthorized changes or malicious payloads can alter PLC logic and data. Famous incidents such as Stuxnet and TRITON show that manipulated PLC code can cause physical damage while logs appear normal. From an incident‑response standpoint, tampered logic can look a lot like memory corruption until you dig deeper.

Recognizing Early Symptoms Before Logic Is Lost

In my experience, the difference between a painful event and a plant‑wide crisis is often whether someone noticed the early warning signs.

CPU status LEDs are your first line of defense. A red ERROR or FAULT LED almost always indicates a problem in self‑diagnostics or program execution. Some platforms use separate ALARM indicators for timer or scan‑time issues, for example loops that never complete. Battery indicators, often labeled BATT, show low backup voltage and should trigger action well before data is lost.

I/O module LEDs often provide the next level of detail. Logic LEDs on output modules and PWR LEDs on inputs help you determine whether the PLC program is trying to drive a point that is not responding, or whether the signal is not reaching the CPU at all. They cannot detect every fault, but they can quickly separate field wiring issues from deeper controller problems.

Symptoms of impending memory trouble often include erratic I/O module behavior, intermittent network communication, unexplained resets, and modules or CPUs that run hot. Maintenance guides describe corrupted memory as causing program errors, data loss, or system crashes, sometimes in combination with electrical noise, power supply instability, or ground integrity problems.

When resource exhaustion is the root cause, the signs are more subtle. Compiler warnings about blocks being “too large for the PLC memory,” dramatic increases in scan time, or diagnostic registers showing high memory usage are common. A LinkedIn advisory on troubleshooting memory and CPU usage recommends using vendor tools to view memory consumption per block, subroutine, or data table, and to correlate spikes in cycle time or CPU load with specific logic paths.

All of this points to a simple rule. The moment you see memory‑related alarms, battery warnings, or out‑of‑memory messages, treat them as production‑critical even if the line is still running.

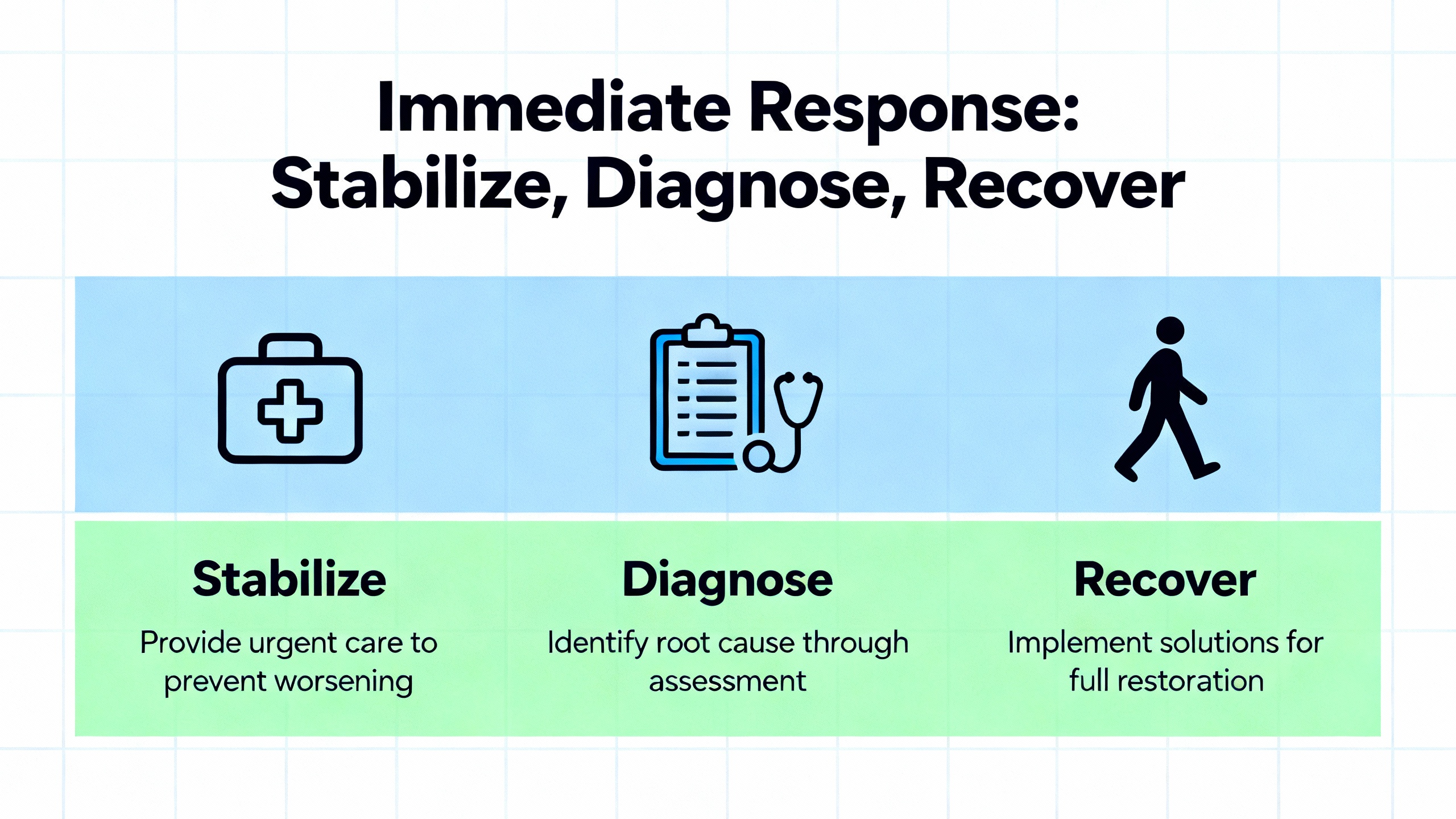

Immediate Response: Stabilize, Diagnose, Recover

When a memory error surfaces, the order of operations matters just as much as the actions themselves.

The first step is to stabilize the process. Talk with operators and supervisors, confirm whether the plant can continue safely, and use emergency stops or safe modes where required. Troubleshooting guides from multiple vendors emphasize starting with safety and clearly documenting the system state, mode, and sequence of events when the problem appeared.

The second step is to capture evidence. Record the exact error messages, status LEDs, and diagnostic codes from the PLC and any associated HMIs or SCADA systems. Note date, time, and recent events such as power dips, storms, production changes, firmware updates, or maintenance work. If your PLC software supports it, save the current project, upload the program from the PLC, and take screenshots of diagnostics before making changes.

The third step is to classify the memory problem. If retentive data such as counters, recipes, or clock values have been lost but the program still runs, a battery or RAM retention problem is likely. If the controller will not start, reports program checksum failures, or cannot load blocks, the non‑volatile program store may be corrupted. If the controller reports that blocks are too large, or memory usage is at or near one hundred percent, you are contending with resource limits or a possibly degraded memory module.

Once you know what category you are in, recovery becomes more straightforward.

When non‑volatile program memory is corrupted, the cleanest path is often to reload a known‑good backup. Troubleshooting references recommend comparing the running program with a master backup to verify integrity. RL Consulting emphasizes structured backup routines precisely so a corrupted file or sudden hardware failure does not stop production for longer than it takes to download a validated project.

Ideally, you restore to a test PLC or a simulator first, particularly if there is any chance of configuration drift, firmware mismatch, or HMI alignment issues. Engineering sources highlight the value of PLC simulators and virtual testbeds for validating behavior safely before applying to a live controller.

If you suspect hardware degradation, for example a failing EPROM or flash module, recovery may require swapping the memory module or entire CPU and then downloading the program. The Siemens example where one PLC of a given type accepts a block and another rejects it strongly suggests device‑specific memory hardware issues. In that scenario, it is often faster to move the program to a healthy unit than to keep fighting with a marginal one.

Throughout recovery, make only one change at a time, test results systematically, and keep meticulous notes. These habits are repeatedly recommended in PLC debugging and troubleshooting guides and are the only way to avoid fixing one issue while creating another.

Designing A Solid Backup Strategy For PLC Program Memory

Memory errors are much less frightening when you know exactly which backup you will load and how long it will take.

The first design decision is scope. According to DigiKey, PLCs can store user programs, setup parameters, data registers, comment data, and entire DM areas as initial values. Maintenance and control‑system specialists also recommend backing up CPU configuration, communication settings, and any tightly coupled HMI or SCADA projects. RL Consulting stresses the importance of accurate as‑built drawings and programming notes alongside the program file, since wiring and configuration documentation can save hours during a crisis.

The second design decision is storage. Articles on memory corruption and PLC troubleshooting emphasize keeping backups on redundant media stored away from electrical noise, extreme temperatures, and humidity. That means at least one offline copy on secure storage in a controlled environment, plus one or more copies in your CMMS or engineering document system. The goal is to avoid the situation where the only “backup” is a laptop that has not been synchronized in years.

The third decision is frequency. A maintenance guide from eWorkOrders recommends routinely backing up PLC programs, often at least twice a year, as part of preventive maintenance. RL Consulting suggests quarterly inspections and annual full reviews in heavy‑duty industries such as steel or pulp and paper. They also recommend specific backup triggers: after production changes, following adverse events such as power surges or lightning, and before and after firmware or software updates.

The fourth decision is control of changes. Debugging and maintenance articles advocate using version control to track program revisions, support rollback to known‑good configurations, and record who changed what and why. Even simple version control, combined with a clear naming and storage convention, transforms recovery. Instead of guessing which file is current, you select the version tagged as accepted and tested for that line and date.

Finally, think about restoration testing. Schedule periodic drills where you load a backup into a test rack or simulator and confirm that it runs with current firmware and configuration. This practice reveals stale or incomplete backups before you depend on them in an emergency.

Avoiding Out‑Of‑Memory Errors By Design

Not every memory error is a corruption event. Some are simply the controller telling you that your application has grown beyond what it can comfortably handle.

A practical starting point is visibility. A LinkedIn advisory on PLC memory and CPU troubleshooting notes that vendor tools can display memory and CPU usage per program block, subroutine, data table, and I/O module. Many PLCs expose execution time, scan time, and cycle time counters, so you can see not just that the PLC is overloaded but exactly when and where resource spikes occur.

Once you know which parts of the program are expensive, you can optimize them. An article on Allen‑Bradley PLC memory usage compares the memory cost of different instruction styles. For example, an Examine On instruction might use about four bytes while a Copy instruction uses around one hundred bytes. The author recommends using intermediate Boolean tags to capture the result of complex or frequently reused conditions, instead of repeating long comparisons. This improves readability and reduces overall memory usage when the same condition appears in multiple places.

Add‑On Instructions, or AOIs, act like classes in traditional programming. The underlying logic exists once, and each new instance primarily adds memory for its tag data. The Medium article on Allen‑Bradley PLCs explains that memory savings grow as more instances are created. The trade‑off is that modifying an AOI usually requires a download to the processor, which may be operationally sensitive.

Subroutines are another powerful tool. By encapsulating repeated logic in a subroutine, you use the logic and tags once and pass in different parameters. The same article notes that this can reduce memory even more than AOIs in some cases, especially when the tag structures are large. The downside is that troubleshooting can be more difficult because there is no dedicated logic for each instance and tag values must be traced through shared code.

Arrays and Boolean arrays are a third lever. Instead of writing near‑identical rungs for thirty devices, you can loop through an array within a single rung or routine. The Allen‑Bradley example points out that each standalone Boolean tag uses around four bytes, while an array of thirty‑two Boolean elements also uses about four bytes. Using Boolean arrays instead of many individual tags yields savings with no loss of semantics, particularly when combined with AOIs that treat Booleans as arrays internally.

Beyond structures, structured design practices from RealPars and secure coding projects help keep logic lean. Clear requirements, modular functions, and regular review to remove dead code prevent “fat” programs that waste memory on unused logic. When you combine these techniques with periodic memory usage reviews, out‑of‑memory errors rarely appear without ample warning.

Protecting Memory With Power And Environmental Discipline

No amount of careful programming can compensate for abusive power and environmental conditions. The most robust flash and RAM will eventually fail if they are fed unstable power and baked in dust.

Troubleshooting guides from DoSupply and AES repeatedly start with power and grounding. Confirm that the PLC’s supply voltage is within specified limits, that fuses and breakers are intact, and that there are no loose or corroded connections. Power protection recommendations include installing backup power sources such as UPS units or generators so that PLCs can be shut down properly when grid power fails instead of dropping unexpectedly.

Grounding and shielding are equally important. Ground loops can introduce electrical noise and interfere with signals, contributing to erratic behavior and memory corruption. Technical articles recommend verifying ground integrity, eliminating unintended ground paths, separating low‑level signals from high‑current conductors, and using shielding or isolation transformers when necessary. Reducing EMI and RFI extends PLC life and prevents many intermittent faults that are otherwise blamed on “mysterious” memory problems.

Environmental care is not glamorous but it is essential. Maintenance references describe the importance of keeping dust out of CPUs and I/O modules, regularly cleaning or replacing ventilation filters, and locating PLCs away from excessive heat and vibration. High temperatures accelerate battery degradation and memory failures; DigiKey notes that temperatures above about 77°F shorten battery life and increase data‑loss risk.

Tie these disciplines into your preventive maintenance plans. Make visual inspections of control panels, tighten connections, clean enclosures, and confirm that fans and cooling systems operate correctly. Review environmental trends where available, particularly for cabinets in hot or dirty areas.

Battery Maintenance And Data Retention

Battery management is one of the simplest and most effective ways to avoid memory‑related incidents.

DigiKey explains that backup batteries power the RAM that holds holding areas, DM areas, counter values, and often the real‑time clock. Many PLCs provide self‑diagnostics and indicators to signal low‑battery conditions, but these may be easy to miss unless someone is explicitly checking them.

Best practice is to check backup‑battery voltage regularly and to treat the low‑battery indication as an urgent maintenance item. DigiKey recommends replacing the battery within roughly one week of the first low‑battery warning. During replacement, the new battery should be installed within about five minutes of removing the old one to preserve volatile‑memory data. Exceeding that window risks losing RAM contents even if the flash program remains intact.

Typical PLC battery service life under ideal conditions is around five years, but actual life depends heavily on model, environment, and operating profile. Frequent power outages, long periods with the system powered off, and high ambient temperatures all shorten service life and increase data‑loss risk. For critical controllers, many integrators schedule preventive battery replacement ahead of the theoretical end of life, based on plant history and risk appetite.

Tie battery checks and replacements into the same structured maintenance schedule you use for backups and inspections. Treat low‑battery alarms with the same seriousness you would give to drive overtemperature or safety relay faults.

Security And Integrity: Defending Program Memory From Tampering

Not every unexpected change in PLC memory is accidental. Cybersecurity research makes it clear that PLC programs and data areas are now targets in their own right.

The Top 20 Secure PLC Coding Practices project, supported by the ISA Global Cybersecurity Alliance, focuses heavily on integrity as a primary security goal. The practices address the integrity of PLC logic, variables, and I/O values, and they explicitly include monitoring of memory usage and cycle times as indicators of abnormal behavior. Some guidance recommends using PLC flags as integrity checks, setting dedicated bits to indicate that critical steps have completed and monitoring those flags from separate logic or higher‑level systems to detect impossible states.

An OT cybersecurity guide from TxOne describes how attacks such as Stuxnet and TRITON exploited PLC and safety controllers by injecting or modifying logic. These cases show that even well‑maintained hardware can behave unpredictably if the program is altered maliciously or through compromised engineering workstations.

From a practical standpoint, program memory protection includes both technical and procedural measures. Limit who can access PLC programming ports and who can download new logic. Use role‑based access control and strong authentication where the platform supports it. Monitor changes to PLC programs and configurations through version control and audit logs, and investigate unexpected differences between the running program and the master backup.

Many secure coding references also recommend monitoring for unusual scan times, memory usage, and variable values as part of anomaly detection. Because PLCs normally operate with very stable timing and data patterns, deviations are often meaningful.

These controls do not prevent every incident, but they significantly reduce the chance that your next “memory error” is actually a hidden logic change.

Working With Vendors And Long‑Term Partners

There are times when, despite good backups and careful troubleshooting, a PLC continues to throw memory errors or refuses to accept valid blocks. In those cases, partnering with experienced vendors and integrators is often the fastest path to resolution.

RL Consulting’s maintenance material emphasizes the value of long‑term support relationships where the integrator understands your processes, standards, and installed base. That context allows faster diagnosis when, for instance, one CPU of a given model starts rejecting a program that runs fine on others, pointing to a specific EPROM or hardware defect rather than a programming issue.

Service providers such as AES highlight their role in handling complex electronic repairs, including PLC CPU and memory faults. When CPU circuitry is suspected to be defective, troubleshooting guides often conclude that replacement is the most practical option once power, environment, wiring, and program integrity have been ruled out.

The most important contributor to successful vendor engagement is documentation. Clear as‑built drawings, current program backups, and a log of recent changes allow an external specialist to step into your system without guesswork. That is another reason to treat backups and maintenance records as core assets, not afterthoughts.

FAQ: Practical Questions About PLC Memory Errors

Q: How often should I back up my PLC program and data areas? A: Maintenance references recommend at least semiannual backups for most plants, with more frequent backups in harsh or high‑duty environments. Many practitioners align backups with quarterly inspections, significant production changes, and any firmware or software updates. After adverse events such as power surges or lightning, it is prudent to verify program integrity and take a fresh backup once the system is stable.

Q: When is a memory error likely to be hardware rather than software? A: Persistent program‑block size warnings, failures to download blocks that run fine on identical CPUs, repeated checksum failures after clean downloads, and memory errors combined with abnormal heating or physical signs of degradation often point to hardware issues such as failing flash, EPROM, or CPU circuitry. In contrast, memory problems that correlate with recent code changes, firmware updates, or configuration edits are more likely to be software related.

Q: What is the safest way to handle a low‑battery alarm on a PLC? A: Treat a battery alarm as a high‑priority work order. Verify that the program and configuration are backed up, obtain the correct replacement battery, and schedule a controlled swap. Follow manufacturer guidance, which commonly calls for installing the new battery within a few minutes of removing the old one to preserve volatile data. After replacement, confirm that retentive data and the real‑time clock have remained intact and record the date in your maintenance system.

Q: How can I tell if memory corruption was caused by EMI or grounding issues? A: Clues include correlation with nearby welding or large motor starts, recurrent communication glitches, unexplained sensor noise, and ground‑integrity problems found during inspection. If memory errors and erratic I/O behavior improve after addressing shielding, cable routing, and grounding, EMI is a likely root cause. Multiple technical articles recommend treating grounding and noise control as part of every memory‑related investigation.

Closing Thoughts

Reliable program memory is the quiet foundation of every automation project. You only think about it when it fails, and by then the cost of downtime is already mounting. By understanding how PLC memory actually works, tightening up power and environmental practices, designing disciplined backups, and making smart use of vendor diagnostics and secure coding guidance, you turn memory errors from existential threats into manageable maintenance events.

That is the mindset I bring to every project as a systems integrator and long‑term partner: assume that hardware and power will eventually misbehave, and build your PLC program, backups, and maintenance routines so the plant keeps running anyway.

References

- https://gca.isa.org/blog/top-20-secure-plc-coding-practices-available-now

- https://www.plctalk.net/forums/threads/better-troubleshooting-experience-for-siemens-plcs.141479/

- https://www.empoweredautomation.com/best-practices-for-implementing-automation-plc-solutions

- https://www.aesintl.com/plc-faults-and-troubleshooting-procedures/

- https://blog.ioprogrammo.info/best-practices-for-plc-memory-management-in-automation/

- https://www.plctechnician.com/news-blog/five-common-issues-plcs-how-solve-them

- https://www.realpars.com/blog/plc-programming-mistakes

- https://rlconsultinginc.com/best-practices-for-maintaining-custom-plc-systems/

- https://s4xevents.com/its-out-top-20-secure-plc-coding-practices/

- https://community.br-automation.com/t/plc-memory-error/6654

Keep your system in play!

Top Media Coverage

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shiping method Return Policy Warranty Policy payment terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2024 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.