-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Brewery Automation PLC Control Parts Supply: How To Keep Your Brewhouse Running

The New Reality: Breweries Are Becoming Data-Driven Plants

Walk through any serious brewery today and you will see more than stainless tanks and hoses. You will see temperature probes on every vessel, flow meters on wort lines, level switches in bright tanks, PLC panels by the brewhouse, and operators watching fermentation curves on screens instead of clipboards. Modern breweries blend brewing craft with automation, data, and control hardware.

The Beer Connoisseur Technology Blog has described how automated brewhouse systems now monitor temperature, pressure, and fermentation stages in real time, reducing human error and tightening batch-to-batch consistency. Packaging lines are computer controlled for filling, sealing, and labeling. Digital records track every lot from malt intake to finished case.

At the same time, craft beer competition is intense. The Brewers Association notes that most Americans live within about ten miles of a craft brewery, and defines a craft brewery as small, independent, and under roughly 6 million barrels per year. Thomasnet’s coverage of microbrewery automation points out that small brewers are under pressure to maintain quality and consistency while meeting rising demand, without the massive systems used by the largest producers.

Automation is no longer a luxury reserved for industrial-scale giants. Articles from Thomasnet, SKE Equipment, Rockwell Automation, ABB, and others all converge on the same message: targeted automation, even at small scale, can transform consistency, throughput, and cost. That automation is built on parts: sensors, valves, I/O, PLCs, drives, and HMIs. When those control parts are not available, all the software in the world will not save your brew day.

From the point of view of a systems integrator, PLC control parts supply is not just a purchasing problem. It is a strategic risk and reliability decision that should sit alongside recipe design, tank sizing, and distribution strategy.

What Brewery Automation Looks Like on the Plant Floor

Different vendors describe brewery automation in slightly different language, but the architecture is consistently layered.

ABB highlights a portfolio that spans distributed control systems, PLCs, HMIs, drives, motors, robots, measurement, analytics, and MES. Rockwell Automation describes brewery automation as unified control and information systems from material receipt through production, packaging, and shipping. Clinical Leader’s profile of FactoryTalk Brew and FactoryTalk Craft Brew shows how modular software connects process data, energy management, and performance.

Under all of that, the picture on the floor is concrete. Sensors on the utilities side monitor chillers, boilers, compressors, and pumps. The Processing magazine article on critical brewery equipment describes condition monitoring sensors on boilers for pressure and condensate levels, as well as vibration, temperature, and motor current monitoring on rotating equipment. In the process area, sensors measure pH, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, density, and flow.

During mashing and lautering, temperature, time, and pH sensing maximize enzymatic activity and sugar extraction. In the boil and whirlpool, sensors control wort temperature, evaporation, and hop utilization, keeping whirlpool conditions around roughly 176–194°F for the right duration and clarity. At knockout, temperature, flow, and pressure sensors around the heat exchanger ensure wort cools quickly and repeatably to fermentation temperatures, typically in the neighborhood of 68–77°F for many ales.

Fermentation uses temperature, specific gravity or density, pH, vessel pressure, and dissolved oxygen probes to track yeast performance and carbonation. Filtration and centrifuge stages rely on flow, pressure, turbidity, vibration, and temperature sensors to protect expensive equipment and achieve clarity at cold temperatures. Conditioning and packaging watch tank temperature, dissolved CO₂, pressure, oxygen ingress, and precise fill volumes.

All of these signals land in PLCs or DCS controllers. Those controllers drive valves and pumps, execute recipes as sequences, enforce interlocks for safety, and report data to HMIs, SCADA, and brewery management systems such as Beer30, BrewOps, or Crafted ERP.

Automation does not eliminate the brewer’s art. It gives the brewer a repeatable, observable process. But it also introduces a new dependency: the plant now relies on a relatively small set of control parts staying healthy and available.

Where PLCs and Control Parts Fit In

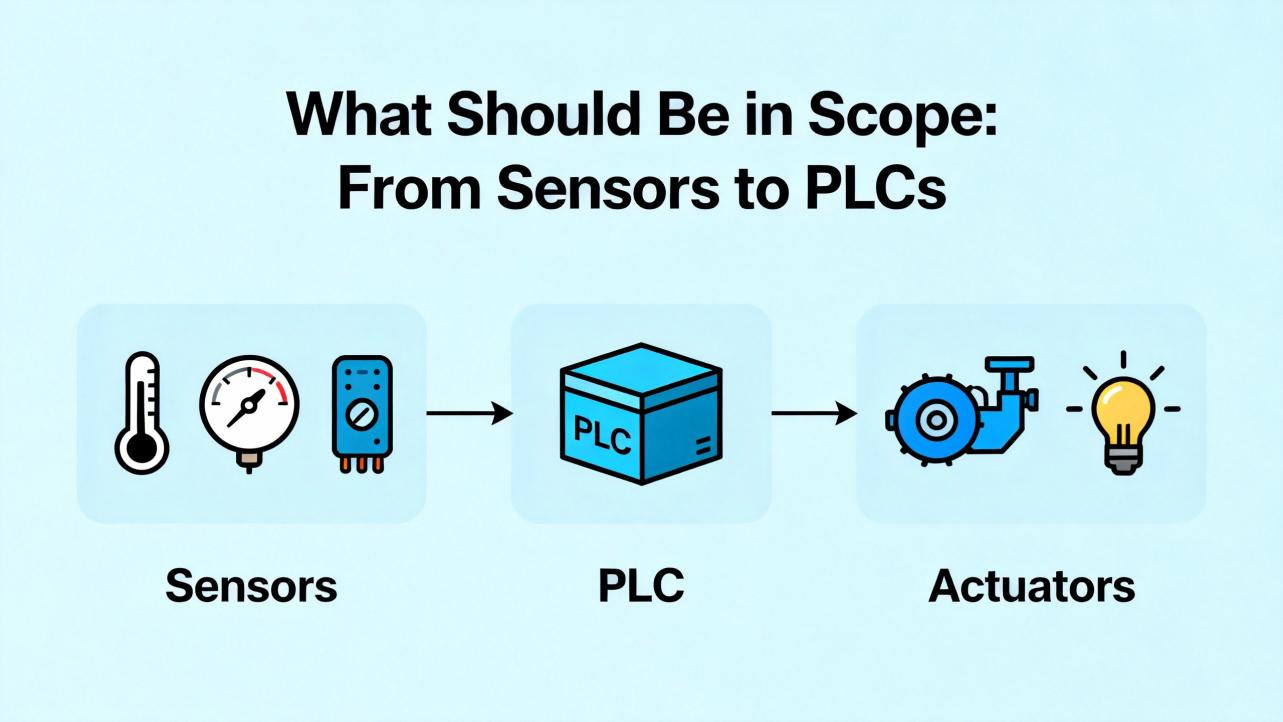

In the brewing context, a PLC is the ruggedized brain that executes your mash profile, supervises knockout, coordinates CIP, and interlocks the packaging line. Sensors and actuators are the senses and muscles of that brain. IO-Link, emphasized by ifm as a backbone of the “connected brewhouse,” provides smart point-to-point communication between sensors and the controller.

The Beer Connoisseur Technology Blog described “recipe management systems” that live in software, storing formulas and step-by-step instructions. Those recipes only become reality when the PLC can read reliable measurements and drive the correct outputs at the right time. Similarly, BrewOps’ case studies and CIP automation tools rely on sensors for conductivity, temperature, and flow to execute standardized cleaning recipes and prove that tanks are actually clean.

From a parts perspective, this means several categories matter:

Sensors and instruments, such as temperature probes, hygienic flow meters, level switches, pressure transmitters, weighing scales, dissolved oxygen probes, pH and turbidity sensors, and conductivity probes for CIP.

Controllers and I/O, including PLC CPUs, remote I/O racks and cards, power supplies, safety relays, and industrial networking components.

Operator interface and drives, such as HMIs, industrial PCs, variable frequency drives for pumps and agitators, and, in some installations, servo drives for packaging equipment.

When we walk a brewhouse for the first time as a systems integrator, we map these devices against each major process area: mill, mash tun, lauter tun, kettle, whirlpool, heat exchanger, fermenters, conditioning tanks, filters or centrifuge, bright tanks, fillers, and utilities. That map is the starting point for a control parts strategy.

The Cost of Getting Parts Supply Wrong

Several of the research sources quantify what is at stake when equipment and controls do not perform.

Clinical Leader describes how upgrading to a fully automated, networked mash filtration system at Full Sail Brewing cut brew cycle time by about 50 percent, increased capacity by roughly 25 percent, and reduced water use by about 1 million gallons annually. Another case study at Sleeman Breweries reports that virtualized process automation increased production capacity by about 50 percent within two weeks, without building a new site.

On the maintenance side, the autonomous maintenance case study at Assela Malt Factory shows what happens when you systematically address equipment reliability. Over an eighteen month project, machine breakdowns dropped by roughly 46 percent per month, average capacities increased, machine idle time decreased, maintenance man-hours dropped by nearly 23 percent per month, and overall maintenance expenses fell by about 64 percent.

These figures are not about PLCs directly, but they underline a simple point: automation and maintenance can unlock substantial capacity and cost savings. All of that is fragile if you cannot replace a failed PLC power supply, a key I/O card, or a critical sensor on a boiler, heat exchanger, or filler.

In practice, the failures that hurt most are often mundane. A level switch in a CIP tank that fails and prevents cycles from starting. A conductivity probe that stops reading correctly, forcing operators to extend rinses and waste water and chemicals. A dissolved oxygen sensor in the packaging line that fails mid-run and leaves you blind to oxygen pickup. A PLC CPU that dies in the middle of the week with no spare on site.

Processing magazine emphasizes that even a single quickly installed sensor on critical equipment can begin delivering value. The corollary is that losing that one sensor can immediately remove that value. PLC control parts supply is about making sure that sensor, controller, or drive is not a single point of failure.

Strategic Drivers for a PLC Parts Program

If you step back from individual components, a coherent control parts strategy in a brewery is driven by four themes.

Quality and brand consistency sit at the top. Sources ranging from The Beer Connoisseur to Craftmaster Stainless and SKE stress that automation is about repeatability and quality. Recipe management systems, automated measurement of temperature, flow, level, pressure, and weight, and integrated quality control reduce batch variability. BrewOps’ case study describes how integrated automation improved batch-to-batch consistency and strengthened brand reputation. Those gains depend on control hardware that stays functional and can be replaced quickly.

Avoiding unplanned downtime and waste is the second driver. Microbrewery-focused articles on Thomasnet and from ifm describe how even partial automation of key measurements helps keep processes in tolerance and avoids rework. The autonomous maintenance case study and the Rockwell Automation case studies make it clear that downtime, idle machines, and frequent breakdowns are expensive. If a failed card strands a brewhouse for a day while you scramble for a replacement, the cost of a single lost brew or dumped batch may dwarf the price of a spare.

Supporting phased modernization is a third concern. Entrust Solutions describes phased automation roadmaps starting with a single vessel and scaling across the facility. Thomasnet and ifm highlight that modern hygienic automation instruments are compact, robust, and affordable enough for microbreweries. Each phase introduces new parts that are now plant-critical. For a small brewery, the control parts strategy has to evolve with each automation step.

Finally, data-driven production and compliance force a long-term view. Crafted ERP, Beer30, Ekos, and BrewOps all showcase how real-time production, quality, inventory, and compliance data support better decisions. Clean-in-place records, traceability from raw materials to finished beer, and automated excise reporting are only as good as the instruments feeding data and the controllers logging it. If sensors routinely fail or control hardware is obsolete and unstable, those higher-level systems never deliver their promise.

What Should Be in Scope: From Sensors to PLCs

The parts portfolio that matters is broader than a PLC CPU and a few I/O cards. The research notes highlight several classes of hardware that should explicitly sit in your parts strategy.

Instrumentation and Sensors

Thomasnet recommends automating process measurements across temperature, flow, level, pressure, and weight. Hygienic thermometers, flow meters, level switches, and scales are designed to withstand washdown and require minimal recalibration once installed. Processing magazine adds dissolved oxygen, pH, turbidity, density, and conductivity to that list, across brewing, filtration, and packaging.

BrewOps’ CIP best practices emphasize conductivity sensors and temperature monitoring in CIP circuits, along with validation tools such as ATP testing or swab tests. Conductivity is used to know when to stop rinsing and when chemical concentrations are correct, directly controlling water and chemical costs.

From an instrumentation parts perspective, the highest-risk items are often those with unique form factors or process connections, such as specific DO probes on the filler, mill protection sensors, specialty flow meters, and CIP conductivity probes. General-purpose temperature sensors and many pressure transmitters may be easier to source quickly, but you still need some coverage for critical locations like heat exchangers, boilers, and primary fermentation.

Controllers, I/O, and Networking

ABB’s brewing portfolio explicitly includes PLCs alongside DCS, HMI, and MES. Rockwell Automation positions integrated control and information systems as the backbone for modern breweries. Clinical Leader explains how FactoryTalk Craft Brew is designed as an entry-level automation platform for microbreweries and brew pubs, requiring minimal engineering staff and offering a customizable interface.

In practice, most breweries end up with a small set of PLC platforms and remote I/O families, often one main platform in the brewhouse and cellar and occasionally a second platform inherited with packaging or utilities skids. Control parts here include CPUs, communication modules, standard and safety I/O cards, power supplies, and industrial switches or Ethernet devices.

Because these components are not interchangeable across vendors or sometimes even across major firmware generations, they deserve priority in your spares plan. If you have just one brewhouse PLC and it fails without a spare, retrofitting an entirely different platform in the middle of a busy production month is not realistic.

Drives, Starters, and Operator Interfaces

Drives and HMIs may not fail as frequently as small sensors, but when they do, the impact is immediate. ABB, Craftmaster Stainless, and Rockwell Automation all emphasize the role of drives and HMIs in energy efficiency, process control, and productivity.

Key examples include variable frequency drives on critical pumps and agitators, and HMI panels used for brewing, fermentation management, and packaging. Many breweries have at least one “master” HMI whose loss would significantly slow or halt operations. While stocking every drive and HMI as a spare is rarely feasible, identifying a small number of standard units that can substitute in multiple locations is a practical approach.

Designing a Practical PLC Control Parts Supply Strategy

Turning this into a working program means moving from abstract risk to concrete decisions.

A sensible starting point is to classify assets by criticality. Entrust Solutions’ automation roadmap approach begins with discovery and data collection about processes and pain points. You can borrow that logic for parts planning. Walk each process area and ask what happens if each controller, I/O rack, sensor cluster, or drive is unavailable for a day. In the brewhouse, a failed mash tun level sensor might be inconvenient but workable for a short time; a failed heat-exchanger temperature sensor or a brewhouse PLC CPU is far more serious.

Next, identify which components are unique and long lead versus standard and quickly sourced. DO sensors specified for low-oxygen packaging, custom CIP conductivity probes, proprietary mill protection devices, and specific PLC CPUs or communication cards often have longer lead times or require specialized configuration. Hygienic temperature probes and many general-purpose pressure transmitters are usually easier to source.

From there, decide what lives on your shelf. Speaking as a systems integrator, I typically recommend that a brewery keep at least one spare PLC CPU for each platform in use, along with a small set of the most common digital and analog I/O cards, a spare power supply per panel family, and at least one general-purpose HMI that can be loaded with different projects. On the instrumentation side, I like to see spare DO probes for packaging and critical fermentation points, a spare CIP conductivity sensor, and one or two spare hygienic flow meters sized for common service lines.

This is not about building a second brewery worth of parts. It is about protecting against the relatively few single points of failure that can stop production, compromise safety, or risk contamination.

Finally, align parts planning with maintenance and improvement practices. The autonomous maintenance study at Assela Malt Factory shows the payback from training operators to inspect equipment, tag abnormalities, and standardize cleaning and inspection. A brewery adopting similar Total Productive Maintenance principles should integrate spare parts thinking into those routines, so that commonly tagged failure modes align with the spares held on site.

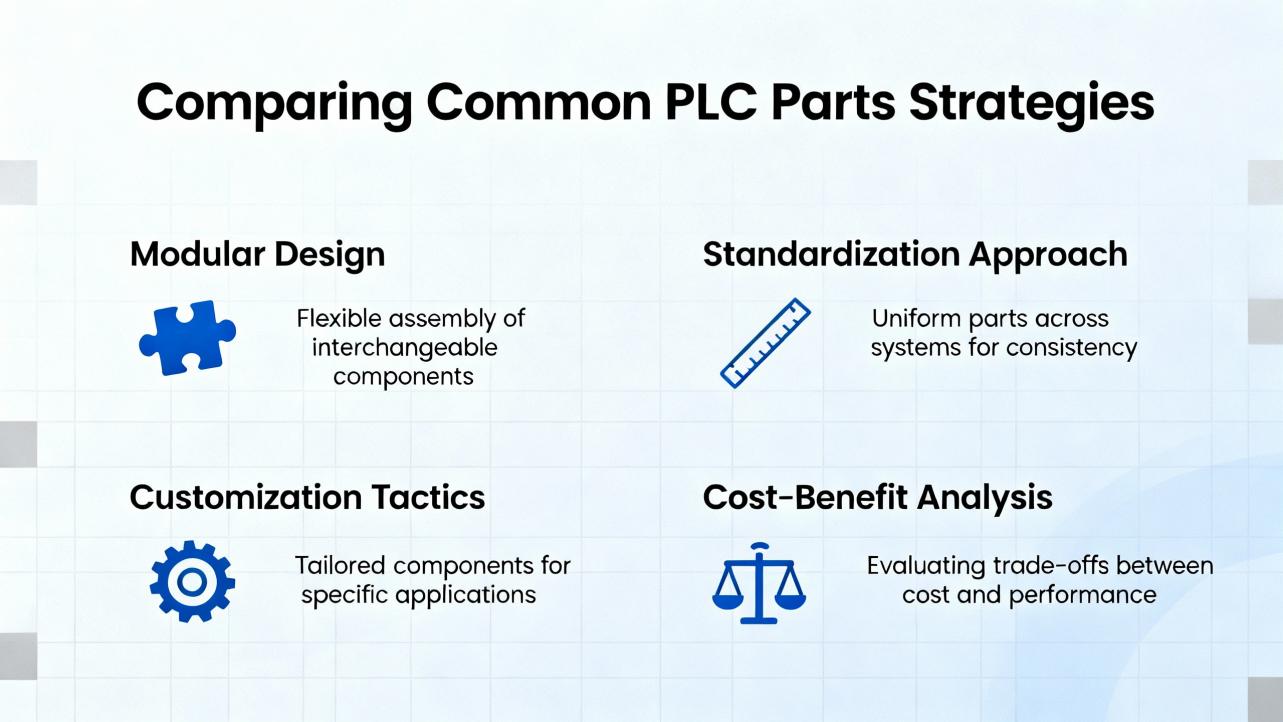

Comparing Common PLC Parts Strategies

Different breweries adopt different approaches to PLC and control parts. The right choice depends on size, risk appetite, and capital constraints. The tradeoffs can be summarized as follows.

| Strategy | Description | Advantages | Tradeoffs and Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal on-site spares with reliance on overnight shipping | Keep only a few universal items and depend on vendors or distributors for rapid shipments when failures occur | Lowest capital tied up in inventory, simple to manage, avoids stocking parts that may never be used | High exposure to shipping delays, stockouts at suppliers, and downtime costs that can exceed savings; stressful during peak season or holidays |

| Targeted critical spares program | Stock a carefully selected set of PLC CPUs, I/O cards, power supplies, key sensors, and a few drives or HMIs based on risk analysis | Balances cost and risk, protects against major outages, focuses attention on truly critical hardware | Requires upfront analysis and periodic review; still some risk for non-stocked items, especially in older systems |

| Deep on-site inventory | Maintain extensive spares for most control components, including duplicates of many sensors and drives | Maximum resilience to single-point failures, often fastest recovery time, strong support for aggressive uptime targets | Significant working capital tied up, risk of parts aging out or becoming obsolete, more demanding inventory management |

| Vendor or integrator managed inventory | Use a control vendor, distributor, or systems integrator to manage consignment stock or guaranteed-availability parts for your platforms | Offloads planning and logistics, can leverage vendor forecasting and regional stock, useful for multi-site brewers | Requires clear agreements and performance monitoring, still reliant on external supply chain, may not cover every specialized item |

From a systems integrator’s perspective, the most sustainable model for many breweries is the targeted critical spares approach, enhanced by some form of vendor or integrator managed inventory for the most expensive or rarely used items.

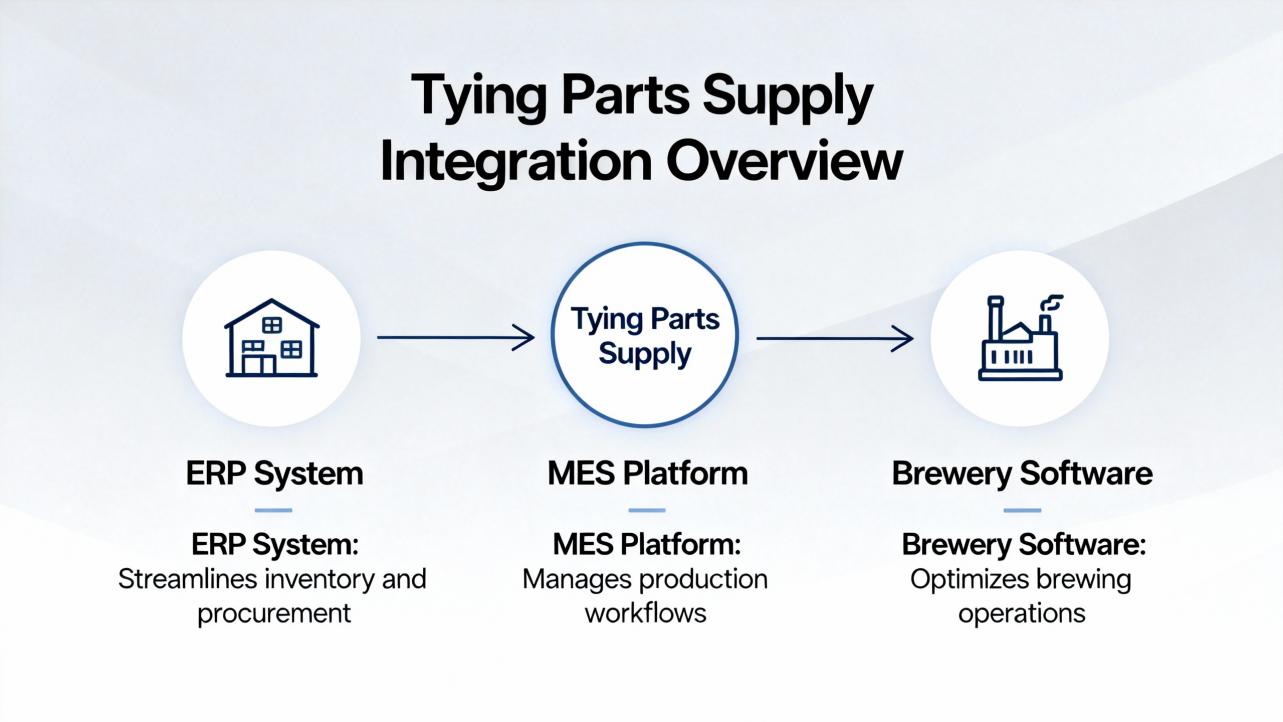

Tying Parts Supply into ERP, MES, and Brewery Software

Brewery automation is increasingly data-driven at the software layer. Crafted ERP defines brewery automation as using integrated ERP software to manage inventory, production, compliance, sales, distribution, and CRM in one platform. Beer30 focuses on brew-to-package workflows with detailed batch data, cost of goods calculations, and demand-driven scheduling. Ekos emphasizes automating inventory and administrative tasks such as TTB reporting and integrating with POS and accounting to provide a single source of truth.

Most of these platforms today are used primarily for ingredients, packaging materials, finished goods, and administrative data. However, the same logic applies to PLC and control parts.

Crafted ERP’s automated reordering based on inventory thresholds and demand forecasting can just as easily trigger purchase orders for spare DO probes or PLC power supplies as for hops and kegs. Beer30’s visibility into brewing schedules and tank usage can inform when certain sensors are heavily utilized and due for replacement. Ekos shows how breweries lose time and money when they live in scattered spreadsheets; the GO Ekos article notes that some breweries spend more than ten hours per month on regulatory reporting and pay around $250 extra per rushed ingredient order when inventory is mismanaged.

Connecting control parts to the same digital backbone helps avoid the equivalent of rush orders for PLC hardware. If a DO probe used across multiple high-volume beers is consistently nearing end of life, demand planning tools can trigger reordering before you find yourself searching frantically during canning.

At the execution layer, Manufacturing Operations Management and OEE tools, such as those highlighted in ABB’s brewing automation offering, help identify chronic bottlenecks and loss categories. When OEE data shows frequent micro-stoppages tied to specific instruments or control loops, that is a clue that the spare parts plan may need to prioritize those devices.

Implementation for Different Brewery Scales

The right starting point differs for a taproom-scale brewery versus a regional producer.

A microbrewery or brew pub often begins with limited automation: perhaps automated temperature control on fermenters, a few flow meters and level switches, and a simple PLC-driven brewhouse. Thomasnet’s guidance stresses that even partial automation of temperature, flow, level, and pressure can materially improve consistency and operator workload. FactoryTalk Craft Brew, as described in Clinical Leader, is designed for these environments with minimal instrumentation and simpler interfaces.

For this scale, a lightweight but deliberate control parts plan is appropriate. That might include one spare PLC CPU, one or two spare I/O cards, at least one spare temperature probe compatible with fermenters and the brewhouse, a spare level switch for critical tanks, and a DO probe if you are instrumented for oxygen. The goal is not to mirror every device, but to avoid being down for days due to a single-point failure.

A mid-sized or regional brewery, on the other hand, may already resemble the fully automated plants in the Rockwell Automation and ABB case studies, with integrated control from material receipt to packaging, MES, and specialized instrumentation on utilities and packaging. In that environment, a more structured program is justified: asset criticality ranking, spare parts coverage targets by class, formal vendor agreements, and integration of parts inventory into ERP.

BrewOps’ case study of a mid-sized craft brewery illustrates the stakes. After automation, the brewery achieved more consistent quality, higher operational efficiency, and scalable production without sacrificing character. Predictive maintenance tools and real-time monitoring kept equipment healthy. Those benefits are easier to sustain when critical control parts are deliberately supported.

Planning PLC Parts Supply as Part of Automation, Not Afterward

The Brewers Association’s “Planning for Automation” guidance is blunt: automation is like any other large project; the more you prepare, the better the result. Doing automation incorrectly leads to headaches rather than better beer. That message applies directly to PLC control parts supply.

When we plan brewery automation projects, we now treat parts strategy as an integral workstream rather than an afterthought. In early discovery, we capture not only process steps and quality targets, but also existing hardware platforms, obsolescence status, and supply chain realities for each major component family. During data collection and facility evaluation, as Entrust Solutions describes, we inventory critical sensors and control devices along with mechanical equipment.

The automation roadmap then includes both functionality phases and support phases. It lays out not only when to add new control sequences or integrate new tanks, but also when to standardize platforms, introduce IO-Link where appropriate, update firmware, and adjust control parts holdings. The goal is a living plan that recognizes that parts supply has to evolve as automation grows.

Short FAQ

How much should a brewery invest in PLC and control spares?

There is no universal dollar figure, and the research does not provide one. The right investment depends on your production volume, the cost of downtime, and the uniqueness of your hardware. As a rule of thumb from project experience, breweries should first protect the handful of components whose failure would clearly stop production for more than a day and for which replacements are not guaranteed to be available locally. Starting with that risk-based set usually yields a sensible initial investment, which can then be refined as you gather data on failures and lead times.

Can we rely on overnight shipping instead of stocking parts?

Ekos shows that breweries relying on last-minute ingredient shipments often end up paying roughly $250 extra per expedited order, plus the hidden costs of schedule disruption. The same pattern applies to control parts. Overnight shipping sounds attractive until there is a regional shortage, a holiday, a weather event, or a discontinued part. Many breweries do successfully use fast shipping for non-critical items, but relying on it for PLC CPUs, unique DO probes, or communication cards is a risk that should be consciously evaluated, not assumed away.

When should we standardize platforms or replace aging controllers?

Several sources, including Rockwell Automation, ABB, and the Clinical Leader case studies, frame modernization as a way to achieve more capacity, better quality, and lower energy and water use without necessarily adding new buildings. In practice, breweries often reach a point where keeping obsolete controllers alive with scavenged parts is more expensive and risky than planning a phased migration. If you find yourself buying used PLCs to keep a line alive, or if your spare parts list is full of components that vendors classify as obsolete, it is time to align platform modernization with your broader automation roadmap and spares strategy.

Closing Thoughts

Modern brewing is still about malt, hops, yeast, and water, but it is also about sensors, PLCs, drives, and the supply chains that keep them available. The research is clear that automation can deliver better quality, higher capacity, lower costs, and stronger compliance. As a systems integrator and project partner, I have also seen how fragile those gains become when a single failed controller or sensor leaves a brewery waiting on a part. Treat PLC control parts supply as part of your automation design, not as a rainy-day expense, and you will brew with more confidence, fewer surprises, and a far more resilient operation.

References

- https://www.academia.edu/10047240/Autonomous_Maintenance_A_Case_Study_on_Assela_Malt_Factory

- https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1086&context=envstudtheses

- https://hammer.purdue.edu/articles/thesis/Evaluation_of_the_techno-economic_and_environmental_performance_of_craft_beer_production_A_case_study_on_microbrewery/11923125/1/files/21897018.pdf

- https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc736119/m2/1/high_res_d/819468.pdf

- https://www.brewersassociation.org/seminars/planning-for-automation/

- https://www.beerandbrewing.com/turning-brewery-challenges-in-to-growth

- https://blog.thomasnet.com/how-automation-improves-microbrewery-processes

- https://www.brewops.com/case-study-transforming-a-brewery-with-brewops-automation/

- https://www.clinicalleader.com/doc/brewery-production-software-automation-and-control-systems-0001

- https://craftederp.com/the-buzz/brewery-automation-transformation

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment