-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 21500 TDXnet Transient

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

Fast Delivery Of Critical I/O Cards: How A Systems Integrator Thinks About Urgent Module Shipping

When a control system is running smoothly, few people think about the I/O cards buried in a panel or a rack. As a systems integrator, I tend to think about them most once something has gone wrong: a PLC rack drops an input bank, a motion system loses its analog outputs, or a safety loop goes dark. In those moments, the conversation shifts from “What’s the root cause?” to “How fast can we get a replacement card on site without making things worse?”

This article looks at fast delivery of critical I/O modules from a project partner’s standpoint. It ties together how I/O cards actually work in industrial systems, what happens when they fail, and how to combine expedited logistics with pragmatic engineering so that urgent shipments are effective, not just expensive.

I will lean on reputable references along the way. ACS Industrial Services has decades of hands-on experience repairing I/O cards for major PLC families and has published practical guidance on what these cards are and how they fail. Contec has documented the technical basics behind analog I/O hardware. Allied Circuits has written about I/O checkout and documentation during commissioning. On the logistics side, Currentscm explains expediting as a structured procurement function, UPS and Old Dominion describe time-critical freight services, and several shipping specialists discuss best practices for moving sensitive electronics safely. The goal here is to translate those perspectives into something you can actually run with on your next crisis job.

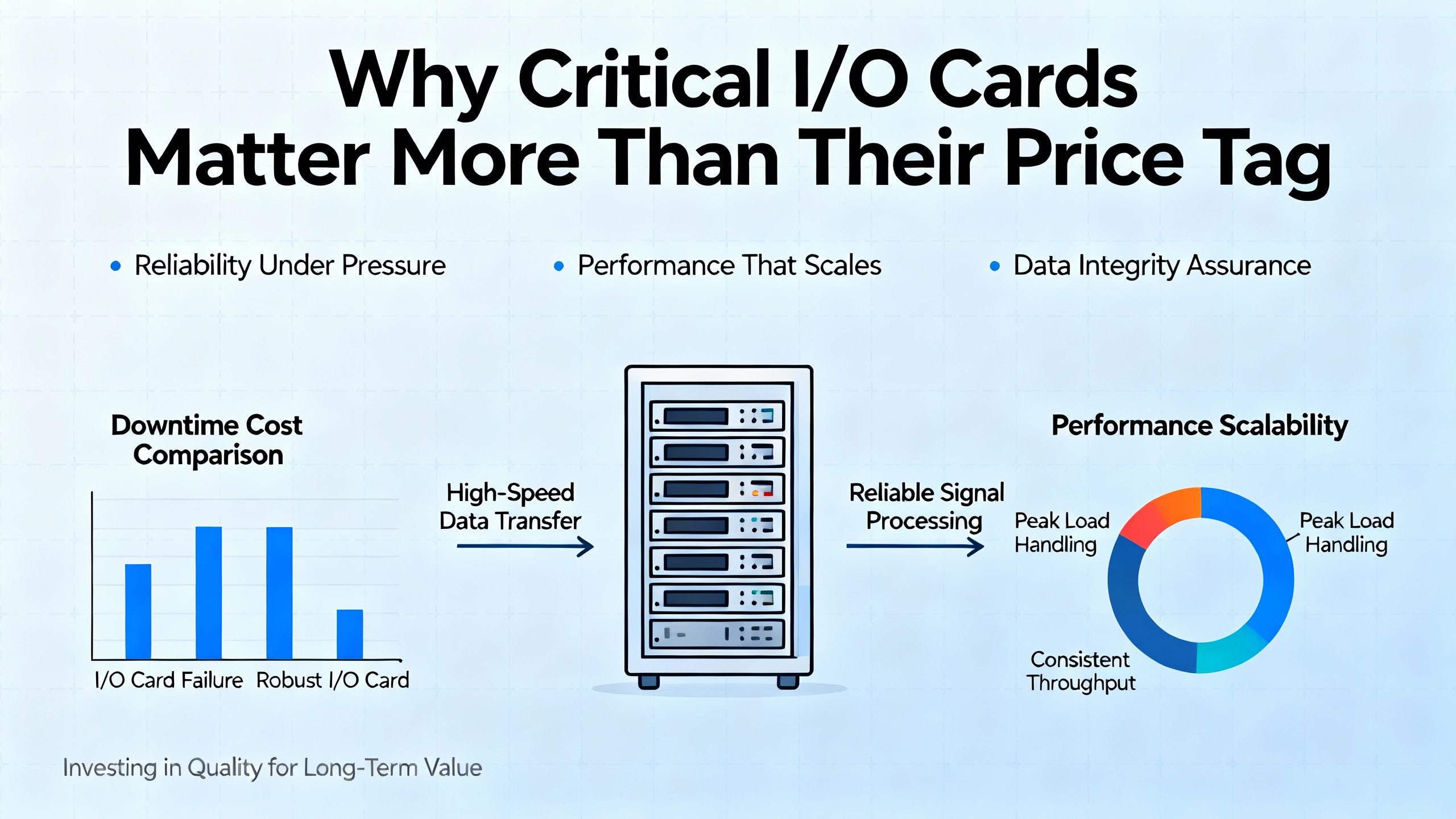

Why Critical I/O Cards Matter More Than Their Price Tag

In a control system, I/O is not a peripheral; it is the system’s senses and muscles. ACS Industrial points out that an I/O card is the bridge between a computer or PLC and the outside world. In a plant, that external world is made up of limit switches, pressure transmitters, drives, valves, and safety interlocks. The card accepts electrical signals from field devices on the input side and drives actuators on the output side.

ACS also reminds us that I/O operations fall into three functional groups: sensory operations, control operations, and data transfer. Sensory devices bring in measurements and state. Control devices convert the PLC’s decisions into electrical commands. Data transfer interfaces move information in and out of the system using methods such as programmed I/O, interrupt-driven I/O, or direct memory access.

In a typical PLC, the controller scans inputs, executes the user program, updates outputs, and then performs housekeeping diagnostics in a repeating four-step cycle. If a critical I/O card in that loop is damaged, the PLC may still be “alive,” but the plant is effectively blind, paralyzed, or both. ACS rightly notes that when an I/O card fails, it disrupts the connection between the device and the computer, leading directly to errors and downtime.

That is the context in which “urgent shipping” actually matters. The card itself may be a few hundred or a few thousand dollars. The real cost driver is the lost production every hour the card is missing or misconfigured.

What Makes Industrial I/O Cards Hard To Replace Quickly

From the outside, a control I/O card can look like just another circuit board with some connectors. In practice it is deeply specific to the platform, the signal types, and the plant’s electrical environment.

ACS notes that what many people casually call an I/O card can also be labeled an interface card, adapter, controller, or expansion card. In industrial systems these are often larger and more complex than a PC expansion board. Contec’s analog I/O overview highlights that even within analog cards you have several intertwined design decisions: analog input or analog output only versus combined I/O, the voltage or current ranges supported, bipolar or unipolar operation, resolution in bits, isolation strategy, and channel topology.

On the input side, Contec explains that the device must map continuous analog values into discrete digital codes. Resolution is finite: in an 8‑bit device you only get 256 steps; in a 12‑bit device you get 4,096; in a 16‑bit card you get 65,536. The usable step size also depends on the configured voltage range. Matching card range and sensor range is essential if you expect to swap cards quickly without having to redesign scaling.

Isolation is another area where cards are not interchangeable. Contec describes non‑isolated designs, bus‑isolated designs using photocouplers between the PC and I/O circuitry, and channel‑to‑channel isolation using isolation amplifiers per channel. The choice affects noise immunity, safety, and how easily you can mix different grounds and signal references. Grabbing a non‑isolated card as a drop‑in replacement for a channel‑to‑channel isolated card may look fine on paper but can be a mistake when you plug into a real plant full of ground loops and electrical noise.

Channel topology matters as well. Single‑ended inputs let you pack more channels into a connector but are more susceptible to noise. Differential inputs use an extra conductor and subtraction (A minus B) to reject common‑mode noise, at the cost of halving the number of channels per connector. Contec highlights this tradeoff clearly. If your plant relies on differential measurement to survive a noisy environment, you cannot trivially swap in single‑ended hardware just because a vendor can ship it overnight.

In other words, when a card fails you are rarely just buying “an I/O card.” You are buying an exact combination of mechanical, electrical, and network characteristics. That is why preparation matters more than heroics once the line is already down.

Know Your I/O Before The Crisis: Documentation And Topology

The best time to prepare for urgent I/O replacements is during design and commissioning, not when the plant is stopped. Allied Circuits’ guidance on performing a successful I/O checkout is worth treating as a template for how you document the system so that later urgent shipments have a realistic chance of working first time.

They emphasize four core documents.

The I/O list is the master reference. It is a table of every input and output point in the control system, covering digital and analog signals and the field devices connected to them. Typical fields include device tag, description, signal type, scaling information, and configuration notes. In practical terms, a good I/O list makes it obvious which rack, slot, and terminal a card and channel belong to. When an I/O card fails, the list is where you quickly confirm what signal types and ranges that module must support.

The schematic wiring diagram is the map of how things are actually wired. Allied Circuits notes that engineers use the SWD during checkout to visually verify signal paths and mark progress. Later, these markups are used to update as‑built documentation. When you are under time pressure with a replacement card in your hand, a complete and current SWD helps you verify that you are landing wires on equivalent terminals and that jumpers, fuses, and isolation barriers are accounted for.

The process and instrumentation diagram links those tags to the physical plant. Allied Circuits points out that P&IDs are often the starting point for building the I/O list itself. During a crisis, a P&ID lets you find the affected pumps, valves, or analyzers in the field so you can decide whether to bypass, simulate, or safely shut them down while waiting for hardware.

Finally, the network and system configuration tells you how the I/O card is seen by the control system. Allied Circuits highlights that modern systems depend on correctly configured networks such as Ethernet, serial protocols, and Modbus. Here is where you find rack addresses, backplane configurations, device IDs, and firmware notes. Without this, you can ship the right physical card and still have it refused by the PLC or network.

These documents are the difference between being able to say “rush me one more of module X in slot 5; I know exactly how it is wired and configured” and “I think it is that card on the left.” The former justifies urgent shipping; the latter turns expedited freight into an expensive guess.

Repair Versus Replacement Under Time Pressure

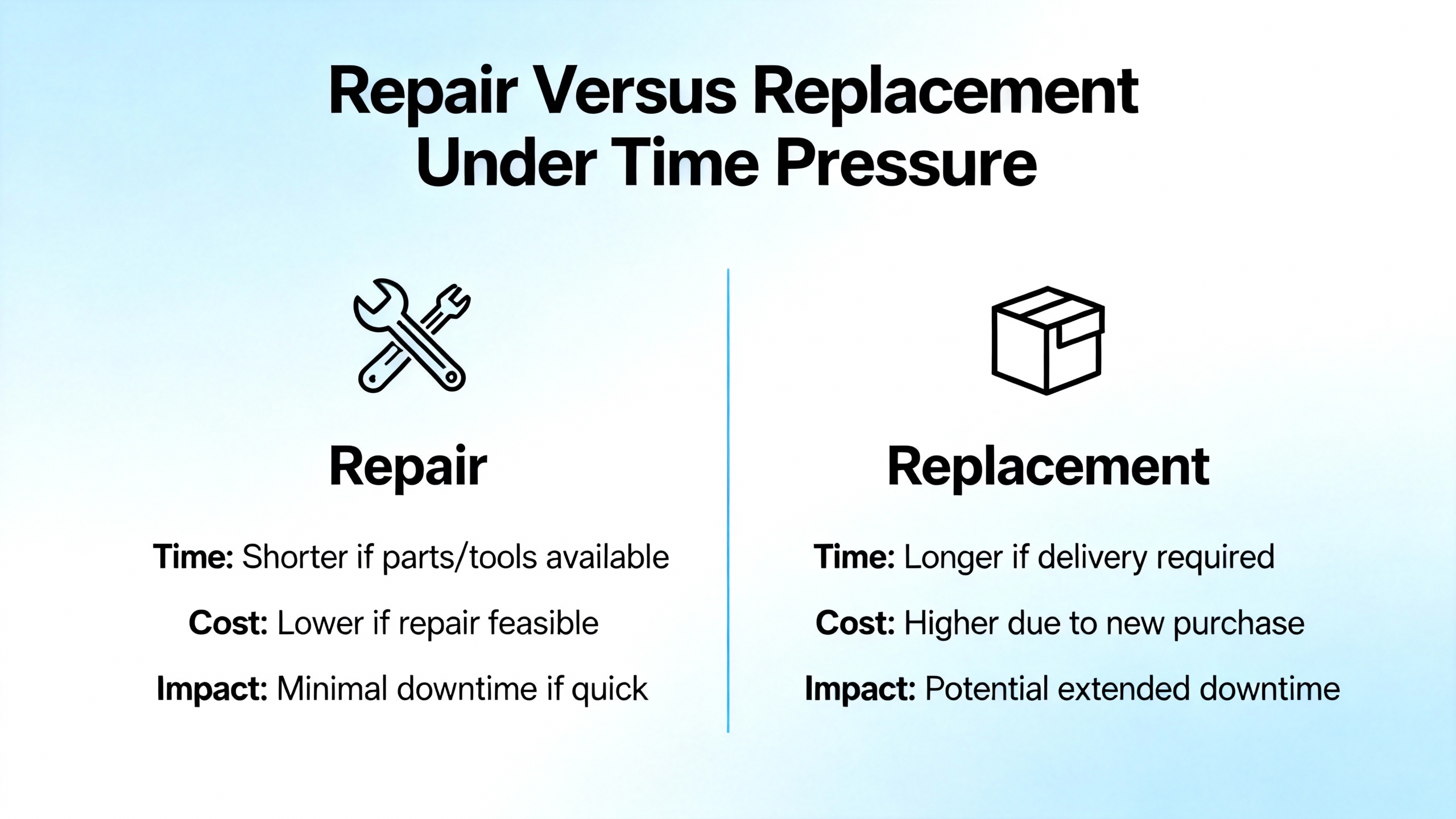

When a critical I/O card fails, you usually have three options in front of you: repair the damaged card, replace it with a new or refurbished one, or redesign to use a different module. Only the first two make sense in a real urgent shipping scenario.

ACS Industrial notes that damaged I/O cards can often be repaired. They report that repairs can save up to about eighty percent of the cost of a new card, depending on the situation, and that they handle brands such as Emerson PACSystems RX3i, Siemens, Rockwell Automation, Mitsubishi Electric, Schneider Electric, ABB, and Honeywell Process. They also provide turnaround guidance: standard repair times around seven to fifteen days, with optional rush repair service targeting roughly two to five days including return shipping.

From a project partner’s perspective, that has clear implications. For non‑critical spares, the economics of repair are compelling. You send the failed card out after a swap, wait a week or two, and restock your shelf at a fraction of the new‑purchase price. For critical cards on which a production line depends, the choice is more nuanced. Even a two to five day rush repair can be too long if the plant cannot run safely without that module.

A sensible structure is to decide up front which I/O types and locations are “repair candidates” and which are “instant replacement only.” High‑availability applications, safety I/O, and cards that underpin major bottleneck equipment often justify purchasing and pre‑positioning a spare, then using repair services like those ACS describes to keep that spare stock replenished. Less critical or rarely used cards can follow a send‑for‑repair‑and‑wait model.

The important point is that repair lead time and shipping lead time must be treated as a single chain. If you need a refurbished or repaired card to be back on the panel in two days, then both the bench work and the shipping need to be planned as one urgent process, not as two unrelated activities.

Urgent Logistics Is A Discipline, Not Just Paying For Overnight

Procurement professionals have long treated expediting as a separate discipline. Currentscm describes expediting as a core function that does more than just push suppliers; it proactively ensures on‑time delivery of materials, services, and documents while maintaining quality.

They outline three stages that map surprisingly well onto getting a critical I/O card to site in a hurry.

The preparation stage focuses on identifying critical items, gathering order details, and setting clear communication channels. For an I/O card, this means that before anything fails you have already tagged certain part numbers as critical, you know their exact specifications from the I/O list and SWDs, you have vetted suppliers or repair houses, and you know who on the engineering side can approve substitutions.

The proactive monitoring stage is where expediters review lead times, hold regular check‑ins with suppliers, and track milestones rather than waiting for promised ship dates to slip. Applied to urgent I/O, this means that once you place a rush order or send a card out for rush repair, someone is actively watching its status, confirming that bench work starts when promised, checking that shipping labels are correct, and updating site teams with realistic estimates of arrival.

Timely intervention is about resolving issues when things do go wrong, escalating when necessary, and documenting communication. For critical I/O shipments, that might involve approving an upgrade from ground to air, switching from standard LTL freight to an expedited service, or splitting an order so that at least one card can be delivered by the fastest method available.

Currentscm also makes a point that expediting should be selective. Trying to expedite everything overwhelms both internal teams and suppliers. That guideline translates directly to I/O: not every module is worth a premium shipping strategy. Focus expediting on the cards whose absence truly stops production, compromises safety, or delays commissioning milestones.

The governance side of this should not be ignored. The U.S. Postal Service’s Supplying Principles and Practices manual, while aimed at postal procurement, emphasizes integrity, transparency, and fairness in dealing with suppliers. Even in urgent situations, it is wise to stay within a pre‑defined framework: use approved vendors, keep clear records of expedited decisions and costs, and avoid one‑off workarounds that will be hard to justify later.

Choosing The Right Transport Mode For Critical I/O Cards

Not all urgent shipments look the same. The best method depends on the size of the shipment, the distance, the risk profile, and how much control you need over chain of custody.

UPS positions its Express Critical service as a premium option for time‑sensitive, high‑stakes shipments. They describe a portfolio of options including next‑flight‑out, expedited ground, charter, hand carry, and highly controlled inside‑facility services. The focus is on the fastest possible time‑in‑transit combined with enhanced chain of custody and elevated visibility. Their use cases include scenarios that look very familiar to plant engineers: out‑of‑stock parts needed to restore a production line, situations where delays have significant financial or human impact, and highly regulated healthcare shipments.

Old Dominion describes its expedited less‑than‑truckload service as aimed at shippers with the highest demands on transit time and delivery precision. It emphasizes guaranteed delivery times and alignment with strict delivery windows, such as retailer dock appointments. For a critical card that needs to move as part of a small pallet of parts from a central warehouse to a plant, an expedited LTL option like this can be a good fit.

ShipSmart focuses on long‑distance shipping of electronics and appliances at roughly three hundred miles or more. They highlight professional custom packing, anti‑static protection, and white‑glove pickup and delivery. They report a damage rate below two percent, a network of more than three hundred licensed carriers across the United States, and typical cross‑country appliance shipments in the range of about five hundred to fifteen hundred dollars depending on distance, weight, and service level. That kind of service is useful when the I/O card is part of a larger crate of automation hardware or when commissioning equipment is being moved between sites.

Traditional freight distinctions still matter. FreightCenter underscores the difference between less‑than‑truckload and full‑truckload services. LTL is usually the most economical option for sharing a truck with other shippers. FTL costs more but offers more control and is preferred for large or high‑value loads. For a single I/O card, you are usually in parcel or small LTL territory, but when you are shipping a set of racks or a pre‑wired panel, the economics shift toward freight.

A simple way to think about it is that you reserve the most intensive services, such as hand‑carry or chartered flights, for situations where chain of custody and time to restore are mission‑critical. For many industrial I/O emergencies, a combination of rush repair or quick purchase plus an expedited ground or air service is sufficient and far more economical.

Example Matching Of Shipping Approaches To I/O Scenarios

You can think of the logistics choice as another engineering decision to be made alongside technical compatibility. The table below gives a qualitative comparison, grounded in how various providers describe their services.

| I/O scenario | Shipping strategy | Source examples and notes |

|---|---|---|

| Single card needed same‑day or overnight to restart a bottleneck line | Premium air or next‑flight‑out with strong visibility | UPS Express Critical highlights next‑flight‑out, hand carry, and elevated visibility for high‑stakes parts. |

| Small pallet of spare cards moving to a regional service center | Expedited LTL with guaranteed delivery window | Old Dominion positions its expedited LTL service around guaranteed times and appointment compliance. |

| Crated panels or racks containing multiple I/O modules on a long‑distance move | Specialized electronics freight with custom packing | ShipSmart focuses on long‑distance shipments, custom crates, anti‑static protection, and white‑glove service. |

| Non‑critical cards replenishing stock | Standard parcel or LTL with light tracking, no special handling | Currentscm recommends reserving expediting only for truly critical items to avoid overload and cost creep. |

The names in the last column are there to show that these patterns are not theoretical; they are drawn directly from how logistics providers describe their own capabilities.

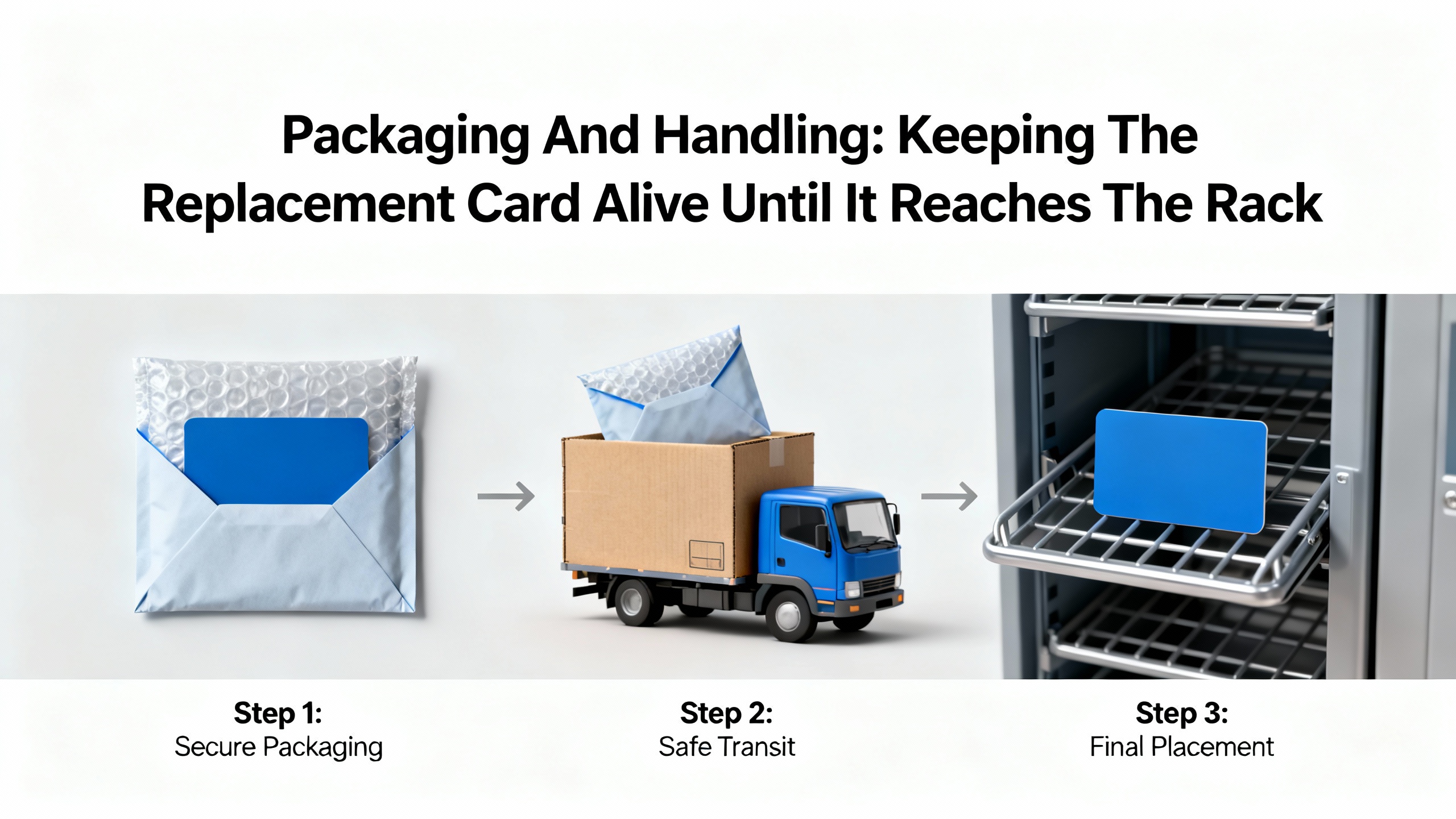

Packaging And Handling: Keeping The Replacement Card Alive Until It Reaches The Rack

A surprising number of “failed” replacements are in fact cards that were damaged in transit. Several shipping specialists converge on the same points about moving electronics safely.

FreightCenter recommends double‑boxing as the best method for packing electronics. The device is placed in a sturdy inner box, which then goes into a larger outer box filled with cushioning between the two. They stress that delicate and high‑value freight demands robust packaging, careful handling, and accurate documentation to avoid damage or loss.

Detailed packing advice from practical guides on shipping electronics aligns with this. The general pattern is to disassemble equipment into as many separate pieces as practical, place small parts and accessories in labeled bags, and wrap each major item in multiple layers of bubble wrap secured with tape so the wrap does not shift. A first box is partially filled with cushioning, the wrapped components are nested so they do not touch, and the voids are completely filled. That inner box is then sealed, placed inside a slightly larger outer box with more cushioning, and the outer box is sealed and reinforced along all seams. The package is then clearly labeled as fragile, with complete addressing and return details.

ShipMonk, in its broader discussion of e‑commerce shipping practices, reinforces that relying on “fragile” labels alone is not enough. They encourage shippers to use a four‑foot drop test and vigorous shaking to make sure packaging can handle normal handling shocks. They also recommend moisture and sunlight protection, using silica gel packs, polybags, and fillers such as airbags, crinkle paper, foam, and bubble wrap.

ShipSmart places additional emphasis on anti‑static protection for electronics and mentions custom wood crating or reinforced boxes. Combined with the previous guidance, a robust approach for I/O cards is to use anti‑static bags around the board, mechanical cushioning around the bag, and then a double‑box strategy to isolate the card from crushing or puncture.

DHL’s guidance on shipping electronics reminds us not to forget battery regulations. Lithium batteries are considered potentially hazardous and require strict labeling, documentation, and packaging. Many modern I/O cards do not include large batteries, but if you are shipping associated equipment that does, it pays to treat dangerous goods requirements as part of the planning rather than a last‑minute surprise.

The common thread is that urgent shipping does not excuse poor packaging. In fact, the faster and more intensively a package is handled through hubs, the more important the packaging quality becomes.

Warehouse And Dock Practices: The Last Fifty Feet Matter Too

Even if you buy and ship the right card, weak shipping and receiving processes can still cause delays. Finale Inventory describes warehouse shipping and receiving as an integrated dock‑to‑dock process. They argue for managing inbound purchase orders and outbound customer orders through a single warehouse management system that provides real‑time visibility and prevents stockouts and “inventory black holes.”

They outline a sequence that includes advance shipment notices, unloading, inspection, goods receipt, putaway, order download, picking, verification, packing, dunnage, carrier booking, and dispatch, with barcode checkpoints at each handoff. For urgent I/O shipments, the critical idea is that tracking should not stop at the carrier’s delivery confirmation. You want the card scanned as received, inspected, and either put away to a known location or flagged for immediate delivery to the maintenance team.

Finale Inventory also suggests realistic targets such as dock‑to‑stock time under about twenty‑four hours for small operations, first‑pass yield around ninety‑five percent or better, and fill rates near ninety‑eight percent. When you are dealing with truly critical hardware, it can be worth temporarily bypassing some of the normal queue so that a card moves from dock to control room in minutes instead of hours, while still maintaining enough scanning and documentation to know where it went.

Their experience with barcoded workflows also reinforces a principle that shows up in multiple logistics references: rely on scanning and system control, not on visual identification and memory. That applies both to inventory storage and to making sure that in a crisis you are not grabbing the wrong card from a bin because labels are ambiguous or missing.

Designing Projects For Fast I/O Recovery

The best urgent shipment is the one you never need because the spare is already on the shelf. Short of that, project design can dramatically influence how painful an I/O card failure becomes.

Contec’s analog I/O explanation is a reminder that every range, isolation, and channel decision you make during design has a consequence for spare strategies. Where possible, standardizing on a small set of card types across panels and lines simplifies stocking and reduces the chance of grabbing the wrong module under stress. Using configurable cards with multiple software‑selectable ranges, within reason, can also make substitutions easier.

The IPO model described by Adobe is a useful way to think about this. They frame processes as Input–Process–Output, and suggest that sometimes it makes sense to start with the desired output and work backwards. For I/O availability, the output you want is clear: the plant must be able to recover quickly from a single card failure without excessive risk or improvisation. Working backwards, the inputs you then need include an accurate I/O list, clear network configuration, standardized hardware choices, spare stock, and pre‑defined logistics channels. The process is the set of technical and procedural steps you follow when a card fails. Mapping this explicitly, even with a simple sketch, often reveals bottlenecks you can fix before they turn into urgent calls.

NextPlus’s discussion of route cards and route sheets, while focused on manufacturing operations, also applies. Route cards are documents that travel with a part, describing the operations and checks it must go through. Route sheets describe the sequence of operations across departments. For critical I/O cards, an equivalent might be a simple traveler that follows the card from storeroom to panel and back again if it is removed for repair. Having a written flow means that when an urgent shipment arrives, everyone from receiving to maintenance understands who does what next.

During commissioning, Allied Circuits’ I/O checkout practices are also a form of preparation for future urgency. If your I/O list, SWDs, P&IDs, and network configurations are fully exercised and updated at startup, you are far less likely to be guessing about a card’s role and configuration years later when it fails.

A Veteran Integrator’s Playbook For Shortening I/O‑Related Downtime

Over many projects, a pattern has emerged in how I approach critical I/O card risk.

The first step is classification. During design or early operation, I sit down with operations and maintenance teams and identify which I/O modules are truly critical. These are usually cards that serve safety systems, bottleneck equipment, or core infrastructure. We document why they are critical and what happens if they fail.

From that classification, we plan spares. For each critical card, we define a minimum on‑site quantity, often at least one spare per unique critical type. We also decide which cards are sent for repair when they fail. ACS’s data on repair cost savings and lead times is helpful here; it makes a strong economic case for repair as long as you are not betting the plant’s uptime on getting a repaired card back within a window that is too tight.

Next, we arrange supplier and logistics options in advance. Borrowing from Currentscm’s expediting framework, we treat urgent I/O orders as a defined process. Approved suppliers are identified, their rush service capabilities are documented, and we agree on who has authority to request upgrades to express shipping or premium logistics options like those described by UPS Express Critical or Old Dominion’s expedited LTL service. We also clarify when specialized electronics shipping services such as ShipSmart are warranted, for example when whole racks or panels are moving rather than single cards.

In parallel, we harden the packaging and receiving routines for these items. Using the combined advice from FreightCenter, ShipMonk, ShipSmart, and practical electronics packing references, we specify anti‑static protection, double‑boxing, cushioning, drop‑testing, and clear labeling as the standard, not the exception. Incoming shipments of critical cards are flagged at the warehouse management level so they are inspected and transferred quickly.

Finally, we drill the recovery process. When a card fails, the team follows a scripted sequence: confirm the failure and its criticality, check for local spares and their configuration, decide whether to swap and send the failed card for repair, or whether to initiate an urgent purchase or repair plus expedited logistics. Throughout, someone is responsible for communication with the supplier and shipper, as Currentscm recommends, and for documenting what was done so that the next similar event is easier.

This is not glamorous work, and it only makes headlines when it fails. Done well, it makes the fast delivery of a critical I/O card almost boring, turning what could be a chaotic scramble into a managed, traceable process.

FAQ

How is an industrial I/O card different from a standard PC expansion card?

ACS Industrial explains that while both are I/O boards that plug into a host, industrial I/O cards are often much larger and more complex. They interface with sensors, actuators, and industrial networks, not just consumer peripherals. They frequently include features such as configurable analog ranges, channel‑to‑channel isolation, industrial communication protocols, and robust connectors designed for harsh environments. A failure has plant‑level consequences, not just inconvenience for a single user.

When is expediting a critical I/O shipment really worth it?

Currentscm emphasizes that expediting should be reserved for truly critical items. For I/O, expediting is justified when a failed card directly stops production, compromises safety, or blocks a milestone such as factory acceptance or site acceptance testing. In those cases, the cost of premium repair and shipping services is usually less than the cost of prolonged downtime. For non‑critical cards, standard lead times and shipping combined with repair services, such as those ACS offers, are often more economical.

Can I trust repaired I/O cards in control and safety applications?

ACS Industrial reports over two decades of experience repairing I/O cards from major automation brands and notes that repairs can significantly reduce cost relative to new purchases. The key is to treat repaired cards as part of a controlled process. That means sending them to reputable repair providers, verifying that they are tested to manufacturer standards, and then checking them in your own system under controlled conditions before they are depended on in a safety loop. Many plants use repaired cards successfully in both control and safety roles, as long as the repair and verification processes are disciplined.

In industrial automation, urgent shipping of critical I/O cards is not just a logistics problem; it is a systems problem that spans design, documentation, repair strategy, warehouse practice, and vendor relationships. If you treat it that way from day one, the next time a card fails you will be solving a well‑defined process, not improvising under pressure.

References

- https://extension.psu.edu/best-practices-for-online-order-packaging-shipping-and-pick-up/

- https://www.mpi.org/docs/default-source/research-and-reports/white-papers/shippingbestpractices.pdf?sfvrsn=d03352d1_2

- https://www.shipsmart.com/shipping-electronics

- https://www.finaleinventory.com/warehouse-management-system-software/warehouse-shipping-and-receiving

- https://blog.acsindustrial.com/i-o-cards/what-i-o-cards-are-and-how-they-work-2/

- https://business.adobe.com/blog/basics/learn-about-the-input-output-model

- https://www.compart.com/en/magazine/document-process-input-output-processing

- https://currentscm.com/blog/expediting-in-procurement-an-essential-guide/

- https://www.fedex.com/en-us/shipping/express.html

- https://www.freightcenter.com/shipping/electronics-and-computer-equipment/

Keep your system in play!

Top Media Coverage

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shiping method Return Policy Warranty Policy payment terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2024 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.