-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Fast Shipping Power Supply Modules: Quick Power Component Delivery

Fast shipping on paper sounds like a logistics problem. In real projects, fast shipping of power supply modules is a design, reliability, and network-planning problem just as much as it is a trucking problem. As a systems integrator who has watched more than one start‑up sequence stall while everyone waited on a missing power module, I treat quick power component delivery as part of the engineering spec, not an afterthought.

This article looks at fast shipping for power supply modules through that lens. We will connect packaging technology, module selection, and logistics strategy so your panels, drives, and control cabinets get reliable power modules when you actually need them, not a week after the production window closed.

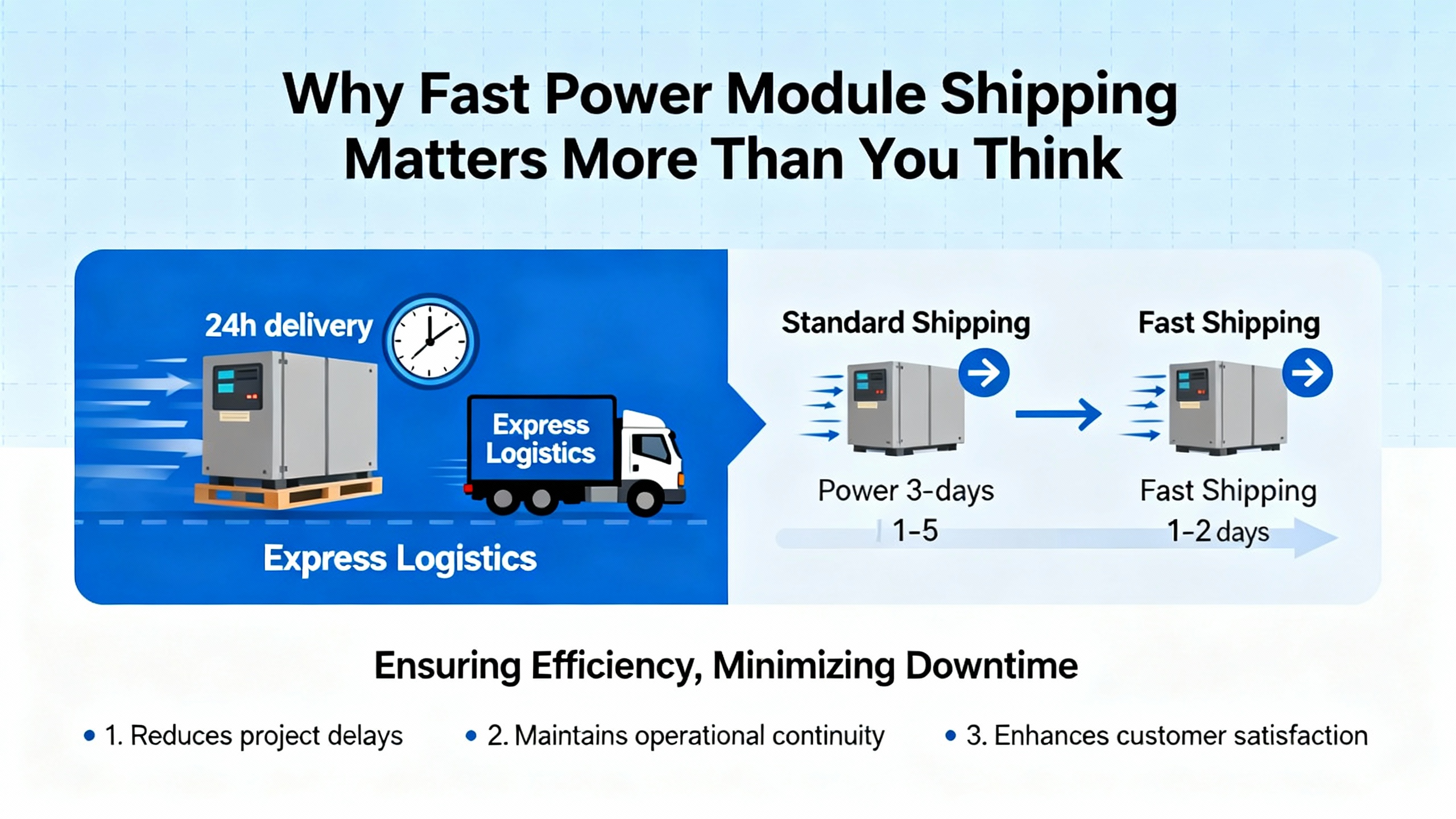

Why Fast Power Module Shipping Matters More Than You Think

In industrial automation, power supplies are not glamorous. PLCs, drives, motion controllers, and industrial PCs get the attention, but none of them boot without stable DC rails and a robust AC front end. That matters even more in data‑center‑like environments, which many modern plants now resemble.

An analysis cited by FSP on data center reliability notes that roughly a third of data loss events in data centers are tied to power outages, with power outranking IT, environmental, and even cyber issues as a root cause. Those numbers come from UL data applied to data center environments, but the lesson carries straight into industrial automation and control: if the power architecture is fragile or delayed, nothing else you engineered will operate as specified.

Fast shipping of power supply modules protects three things at once. First, uptime, because you can swap failed units quickly. Second, project schedules, because you are not redesigning panels late in the game just to work around parts that will not arrive. Third, safety and reliability, because you avoid last minute substitutions that were never thermally or electrically validated in your design.

When we talk about fast shipping in this context, we are not talking about impulse purchases that arrive in two days. We are talking about power components that are standardized, proven, and available through distribution and logistics networks that you or your partner control, with clear lead times and backup plans if lanes fail.

What Power Supply Modules Actually Are

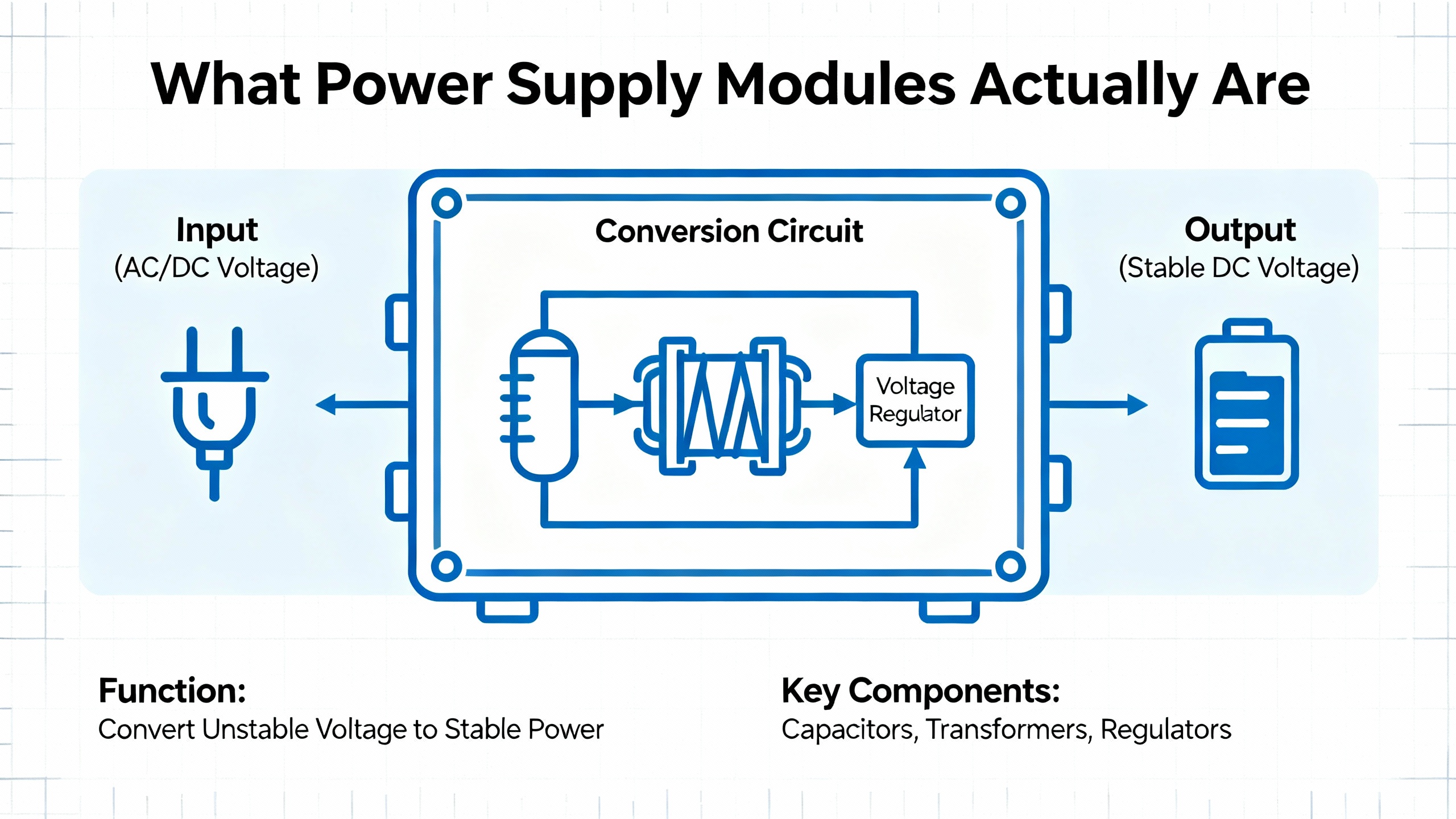

The term “power supply module” gets abused, so it is worth defining it clearly for project teams.

At the low‑voltage end, Texas Instruments describes DC‑DC power modules that integrate the controller, power FETs, inductor, and often key passives into a single surface‑mount package. In one example from TI training on power modules, a 12 amp discrete buck converter—controller, discrete inductor, input and output capacitors, and resistors to set output voltage—occupies about 184 square millimeters of board area. That is roughly 0.29 square inch and yields about 31 amps per cubic centimeter, or around 500 amps per cubic inch of power density. A parametrically equivalent integrated inductor module occupies only about 77 square millimeters, around 0.12 square inch, and achieves about 87 amps per cubic centimeter, roughly 1,400 amps per cubic inch. The module nearly triples power density while cutting board area by more than half.

Higher up the power chain, vendors like Vicor deliver AC‑DC and DC‑DC modules in advanced packages that become building blocks in a power delivery network. Vicor describes modern modules achieving on the order of 10 kilowatts per cubic inch of power density and current densities around 2 amps per square millimeter, using integrated planar magnetics and proprietary control ASICs. These modules let you move from a 48 volt distribution bus down to sub‑volt rails near processors, drives, or AI accelerators with very short copper runs.

At the rack or cabinet level, FSP describes redundant power supply modules built to the Common Redundant Power Supply (CRPS) standard, delivering 2,000 watt Platinum‑rated and 2,400 watt Titanium‑rated modules for data centers and workstations. These modules include I2C or PMBus communication, run efficiently across roughly 32 to 131°F, and are specified up to about 16,400 ft of altitude. They plug into backplanes to form N plus one redundant arrays that you can swap live in a short maintenance window.

All of these belong under the “power supply module” umbrella. They differ in voltage, power levels, and mechanical form, but they share three attributes that matter for fast shipping. They are standardized and well documented, they are built on high‑volume packaging platforms, and they are part of established distribution and logistics networks.

Packaging: The Hidden Enabler of Fast, Reliable Delivery

If you want power modules that ship quickly and survive the journey, packaging matters twice: inside the module itself and around the module in transit.

Inside the Module: Power Electronics Packaging

Semiconductor Engineering reports that the power semiconductor market, driven by electric vehicles and renewables, is expected to roughly double from twenty two billion dollars in 2022 to about forty four billion dollars by the middle of this decade. Packaging and test account for roughly a fifth to a quarter of that market and are becoming critical enablers of power density, switching speed, and reliability.

Traditional silicon power devices worked comfortably at lower voltages and temperatures. Today, wide bandgap devices like silicon carbide and gallium nitride take over many roles. SemiconductorReview notes that these devices can operate at higher voltages and temperatures with higher efficiency and power density, but they rely on adapted packaging and cooling, especially in automotive, renewable, and industrial systems.

Several trends in packaging directly support fast shipping and field reliability:

Semiconductor Engineering describes direct‑bond copper substrates, topside‑cooled packages, and leadless footprints that permit direct heat sink attachment and shorter current paths. Packages like PQFN, TOLL, and chip‑scale formats reduce parasitic resistance and inductance while improving thermal performance. For shipping, smaller, lighter, and mechanically robust packages mean less susceptibility to vibration or impact, and more units per shipping carton or pallet.

Silicon carbide modules need advanced assembly techniques such as heavy‑gauge wirebonding or copper clip structures and high‑conductivity die attach materials like sintered silver. These handle junction temperatures in the roughly 302 to 392°F range while mitigating mechanical stresses caused by different thermal expansion rates of silicon and copper. Better die attach and molding compounds reduce the risk of latent damage from thermal cycling and shock, both in service and during transport.

Embedded substrate approaches integrate dies inside organic laminates with internal copper traces, reducing interconnect length and electrical and thermal resistance. Semiconductor Engineering points to solutions that integrate power and passive components into compact, surface‑mountable modules. For logistics, this integration cuts loose magnetics and components from the bill of materials and replaces them with a single module that you can stock, pick, and ship quickly.

Vicor’s ChiP packages and stacked ChiP solutions illustrate how packaging and power density work together. Two‑sided component assembly on panelized substrates, integrated planar magnetics, and overmolded surface‑mount bodies with large plated surfaces for electrical and thermal contact all support automated manufacturing. Vicor notes that panel‑based ChiP manufacturing works analogously to semiconductor wafer dicing, making it easier to run diverse module variants through high‑volume lines. This manufacturability translates into better availability and shorter restock times when demand spikes.

Around the Module: Shipping Packaging for Fragile Electronics

Once a module leaves the factory or your warehouse, the outer packaging becomes the primary protection. Polymer Molding’s guidance on shipping fragile electronics is directly applicable here.

They recommend strong, size‑appropriate corrugated cardboard boxes, preferably double‑walled, combined with quality cushioning such as foam inserts, bubble wrap, or air pillows. For sensitive electronics, components should be wrapped individually, with extra padding around edges and corners, and anti‑static materials such as pink poly bags or metalized shielding bags used for static‑sensitive parts. Packing peanuts are discouraged because they shift during transport and can leave parts exposed.

Polymer Molding also stresses maintaining an electrostatic discharge safe packing environment with grounded wrist straps and mats and clearly labeling electrostatic discharge sensitive packages. All electrical caps, terminal covers, and connectors should be treated as static sensitive to avoid latent damage that only appears once the module is installed.

Shipping guidance for PC power supplies from other sources aligns with this: use the original packaging where possible, put the unit in an anti‑static bag, then double‑box it with ample foam, and avoid loose accessories bouncing around in the box. For high‑value industrial supplies, I expect the same standard or better.

These practices are not “nice to have” details. A power module that arrives with an invisible cracked solder joint or subtle static damage is more dangerous than one that arrives visibly crushed because you may not catch the damage until after commissioning.

Shipping Compliance for UPS and Battery‑Backed Systems

Fast shipping is pointless if the package sits at the carrier because it violates hazardous materials rules. Lithium‑ion battery regulations are the main issue when you ship uninterruptible power supplies or battery cabinets along with your power modules.

Guidance summarized from UPS rules and related regulations classifies lithium‑ion batteries as hazardous materials governed by the Department of Transportation and the International Air Transport Association. Regulatory requirements extend to classification, packaging, marking, labeling, documentation, and employee training.

UPS requires UN compliant packaging that prevents short circuits, includes non‑conductive insulation, strong outer boxes, and protection against leaks. Packages must be labeled with appropriate identifiers such as UN3480 for batteries alone or UN3481 for batteries packed with or contained in equipment. Handling labels indicating that lithium batteries are inside and that they should be kept away from heat are required.

There are also capacity limits. Typical international air shipments are capped around 300 watt‑hours per battery under standard procedures, with higher capacities requiring special arrangements and approvals. Best practice guidance from the same source recommends shipping lithium‑ion batteries at a partial state of charge, roughly between 30 and 50 percent, to reduce the risk of thermal runaway. Batteries should be inspected for swelling, leakage, or damage before shipment, and different chemistries should not be mixed in one package.

For most industrial automation projects, the immediate relevance is clear. If you are shipping integrated UPS systems, large battery packs, or replacement lithium strings for cabinets, bake these constraints into your logistics plans early. You may decide to ship racks and cabinets without batteries and source battery modules locally under a compliant program. You may also need to train your warehouse or integrator staff on hazardous materials shipping rules and documentation so urgent replacements do not get delayed or rejected.

Fast power module shipping depends on clearing these hurdles cleanly, especially when projects span borders and continents.

Logistics Strategy: Turning Fast Shipping into a Repeatable Capability

Once the engineering and compliance bases are covered, the remaining question is straightforward: how do you design a logistics network that consistently moves power modules where they need to be, as quickly and cheaply as required?

Inventory Positioning and Distribution for Electrical Supplies

Zigpoll’s discussion of distribution optimization for electrical supplies maps almost one to one onto power modules. They define distribution platform optimization as improving the systems, workflows, and technologies that manage inventory, orders, logistics, and customer communication from manufacturer to end customer.

For power modules, that means deciding which SKUs live on the shelf at the plant, which live at a regional warehouse, and which are drop‑shipped or brought in on demand from the manufacturer or distributor. Zigpoll recommends mapping the end‑to‑end workflow, implementing robust data collection via ERP, warehouse management, and e‑commerce platforms, defining clear metrics such as delivery time, order accuracy, and cost per shipment, and putting a cross‑functional distribution team in charge.

They suggest sample targets such as cutting average delivery time from five days down to two days, achieving better than 99.5 percent order accuracy, and reducing cost per shipment by about fifteen percent. You do not have to adopt those exact numbers, but they illustrate the level of rigor required to turn “fast shipping” from a slogan into a measurable capability.

Packaging Efficiency and Dimensional Weight

Shipping cost and speed are tied to package size as much as weight. Next Exit Logistics notes that carriers use dimensional pricing, which charges based on volume as well as weight. Oversized boxes full of empty air drive up freight spend.

They recommend optimizing packaging by matching box size to product size, selecting lightweight yet protective void fill, and consolidating shipments when appropriate. This saves money and reduces damage risk. For power modules, that often means standardized carton sizes and inserts that hold modules securely, rather than ad hoc packing for every shipment.

SupplyChain247 describes fit‑to‑size automated packaging systems that measure each order, then construct, tape, weigh, and label custom boxes on the fly. They report that such systems can process around 500 orders per hour with a single operator, reduce unused space and overall shipping volume by about fifty percent, and cut packing labor by roughly eighty eight percent. For high volume power module distributors, this type of automation can lower costs while preserving or even improving the speed of order cutoffs for same‑day shipping.

Load Planning, Modes, and Last Mile

ProvisionAI highlights that freight represents a large share of supply chain cost and emissions, and that many shippers misunderstand true truck capacity because of bad data and overly conservative loading rules. They argue for measuring real trailer capacity by lane, correcting item master data, planning loads to average rather than worst‑case truck weights, and using optimization tools that produce axle‑legal load diagrams.

For heavy power components—modular UPS frames, battery racks, large AC‑DC supplies—this matters. Under‑loading trailers increases per‑unit freight cost and can force additional runs that compete for capacity with urgent small‑parcel shipments of DC‑DC modules.

DispatchTrack focuses on last‑mile delivery, noting that last mile is a rapidly growing, high‑cost segment of logistics. Customers increasingly expect two day or better delivery and full visibility into shipment status. While these numbers come from consumer and retail scenarios, the expectations spill over into B2B technical deliveries, especially when production lines are waiting.

They emphasize route optimization software, real‑time tracking, flexible delivery windows, and electronic proof of delivery as mechanisms for lowering failed delivery rates, reducing fuel and labor costs, and improving customer experience. Industrial buyers may not care about an app notification on their cell phone, but they do care that the promised delivery actually arrives at the dock during the scheduled maintenance window.

DHL and Inbound Logistics both reinforce that logistics management software—warehouse, order, and inventory systems along with transportation management and network optimization tools—is now foundational. Manual processes and spreadsheet tracking cannot cope with the volume and complexity once your business grows. Platforms referenced by Sophus, Loop, and Emerge emphasize data consolidation, scenario modeling, and dynamic carrier selection as ways to maintain service levels while controlling cost.

When we apply this to power modules, a clear pattern appears. Fast shipping is not just having a few units on a shelf. It is having clean data on dimensions and weight, standard packaging, WMS and TMS systems integrated, accurate carrier performance metrics, and clearly defined service levels for different classes of orders.

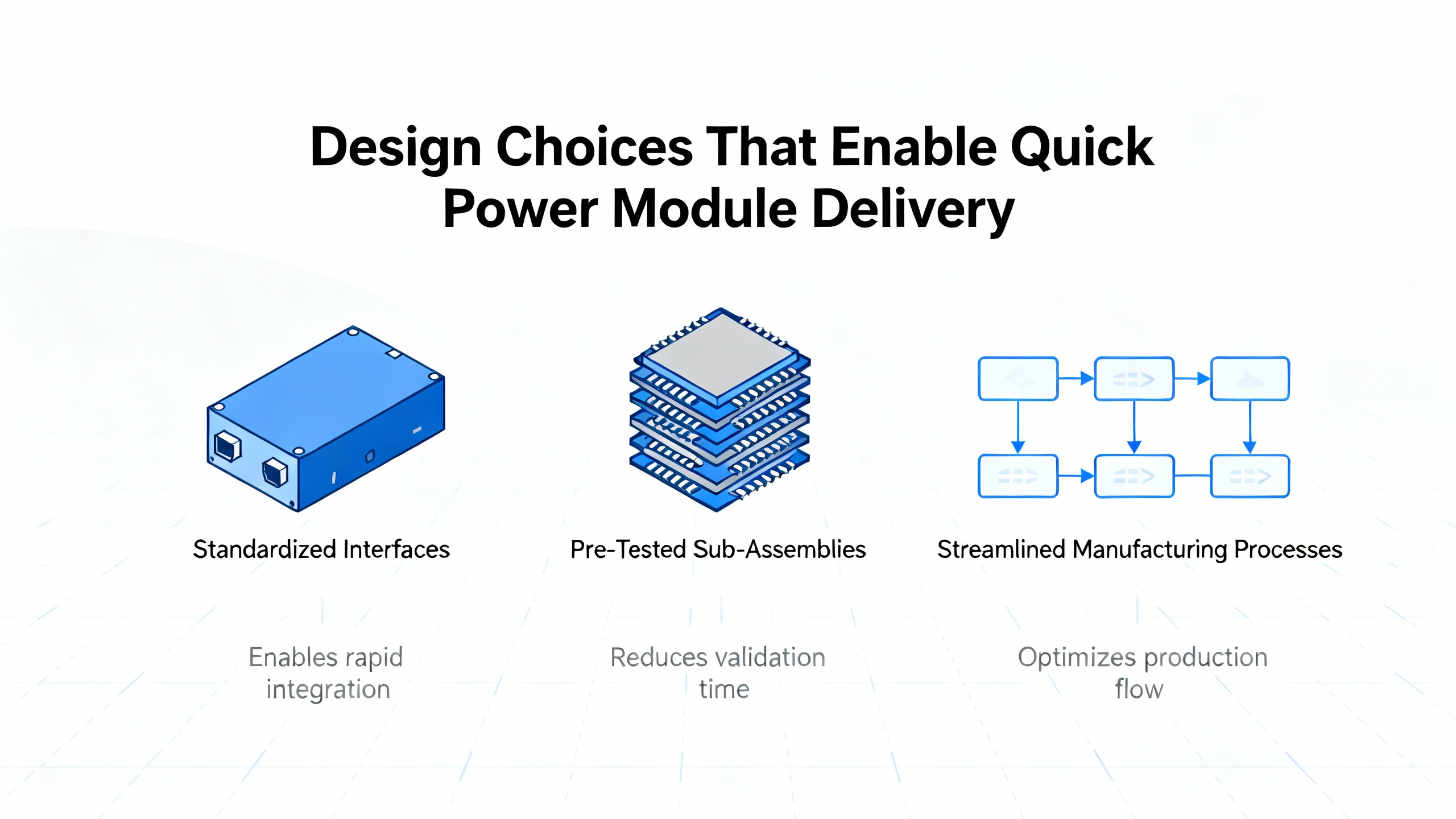

Design Choices That Enable Quick Power Module Delivery

An overlooked lever for fast shipping is how you design your power architecture in the first place. Some choices naturally align with short lead times and easy stocking; others lock you into fragile supply chains and complicated approvals.

Standardizing on Proven Module Platforms

TI’s power module training shows how integrated DC‑DC modules come with evaluation boards and Safe Operating Area curves validated through extensive simulation and thermal testing. Before boards are built, designers run simulations to JEDEC standards and then to the real evaluation board parameters. Once the hardware exists, IR cameras and thermal streams are used to fully characterize behavior under many conditions, and the results flow into SOA curves in the datasheet.

For an integrator, that means less time characterizing and more time designing the system. For logistics, it means standardized SKUs that you can keep in stock at distributors and integrators, with well understood derating rules across temperature and airflow conditions. If one module fails on site, you drop in an identical, validated device rather than recalculating layouts and thermals.

FSP’s CRPS modules offer a similar advantage at rack level. You design a chassis around a standard form factor and power rating, then rely on redundant arrays and hot swap to meet reliability targets. The same hardware building blocks can serve many cabinets and customer configurations, letting you carry a manageable SKU set while still serving diverse needs.

Vicor’s ChiP modules extend this approach to high current point of load delivery from 48 volt buses, especially around data center and AI compute environments. Integrated magnetics, advanced packaging, and panelized manufacturing give you predictable footprints and high power density that are likely to be carried by multiple distributors due to their broad use.

The more your design leans on these proven platforms, the easier it is to find stock quickly anywhere in the world.

Power Density Versus Lead Time: Pros and Cons

The industry push toward higher power density is real and well documented. Semiconductor Engineering and SemiconductorReview both highlight miniaturization, functional integration, and advanced cooling strategies, from heat sinks and heat spreaders to liquid cooling and phase change materials. Vicor points to historical data showing roughly twenty five percent power loss reduction every couple of years as topologies, materials, and packaging evolve.

Higher density brings clear benefits: smaller enclosures, lower weight, and shorter electrical paths with less loss. Those attributes help with shipping as well, because compact modules are easier to pack and carry lower dimensional weight.

There are tradeoffs, though, and they intersect with fast shipping in subtle ways.

Integrated modules reduce design effort and risk because the silicon, magnetics, and layout are co‑optimized and tested. On the downside, you are more dependent on a specific vendor and package. If a single advanced package becomes constrained, you may not have easy second sources. Conversely, discrete designs with separate controllers, FETs, and magnetics offer flexibility and possible cost advantages at volume but increase the number of components that can go out of stock.

In practice, for time‑critical industrial projects, I lean heavily toward integrated modules and standardized redundant supplies where possible, then minimize the number of unique module families in the design. That way my procurement and logistics teams are focusing on keeping a small, well understood set of parts flowing rather than chasing dozens of low‑volume, niche components across the globe.

Redundancy, Hot Swap, and Spares Strategy

FSP’s data center article emphasizes redundant power supplies and modular UPS systems that can absorb failures without losing service. Redundant systems are built from multiple power modules with load‑balancing control, so that if one module fails the others continue supplying power. In server racks, dual power inputs, UPS backup, and smart power distribution units are standard practice.

In industrial automation, especially for critical processes, the same logic applies. If you design cabinets with redundant 24 volt DC supplies or modular AC‑DC fronts, you can stock a small set of spares and restore capacity quickly when a module fails. That directly reduces your dependence on emergency shipping, which is inherently risky.

A practical strategy combines three layers. First, design in redundancy and hot swap capability. Second, maintain onsite spares for the most critical modules, sized against realistic failure rates and lead times. Third, maintain regional or central stocks for less critical or less common modules, backed by fast shipping lanes tuned for two or three day replenishment rather than same day heroics.

Zigpoll’s suggestion of continuous monitoring of metrics such as delivery time, cost per shipment, and customer satisfaction applies here. If your spare strategy and fast shipping program are working, rush orders will be rare, not daily events.

Working With a Fast‑Shipping Power Module Partner

From the outside, a supplier who promises fast shipping on power modules may look interchangeable with any other. From the inside of a project, differences in how they engineer, package, and move those modules make or break your schedule.

When I play the role of project partner rather than simple vendor, I focus on a few concrete practices.

First, shared design standards. We agree early on module families, derating rules, and acceptable equivalents. TI’s use of SOA curves, FSP’s published environmental envelopes, and Vicor’s detailed power delivery documentation make it easier to define these standards clearly.

Second, network and data transparency. Following the guidance from Inbound Logistics, Sophus, Loop, and Emerge, we consolidate data on shipments, inventory, and capacity in a way that lets both sides see where risks are emerging. If a particular module’s lead time is creeping up, we adjust designs, stocking levels, or distribution points before it becomes a crisis.

Third, operational discipline in packaging and shipping. Guidance from Polymer Molding and other electronics packaging experts is turned into standard operating procedures at the warehouse. Boxes, inserts, anti‑static bags, and labels are standardized for each power module family. Warehouse staff are trained not only on how to pack but why it matters, particularly for high power density and static sensitive modules.

Fourth, explicit load planning and carrier strategy. Drawing on insights from ProvisionAI, Next Exit Logistics, and DispatchTrack, we use data to choose when to consolidate freight, when to upgrade to faster modes, and how to structure last mile deliveries to plant sites that may have tight dock schedules and safety rules.

Done well, this kind of partnership keeps power modules off the project’s critical path. They simply arrive, intact, when needed.

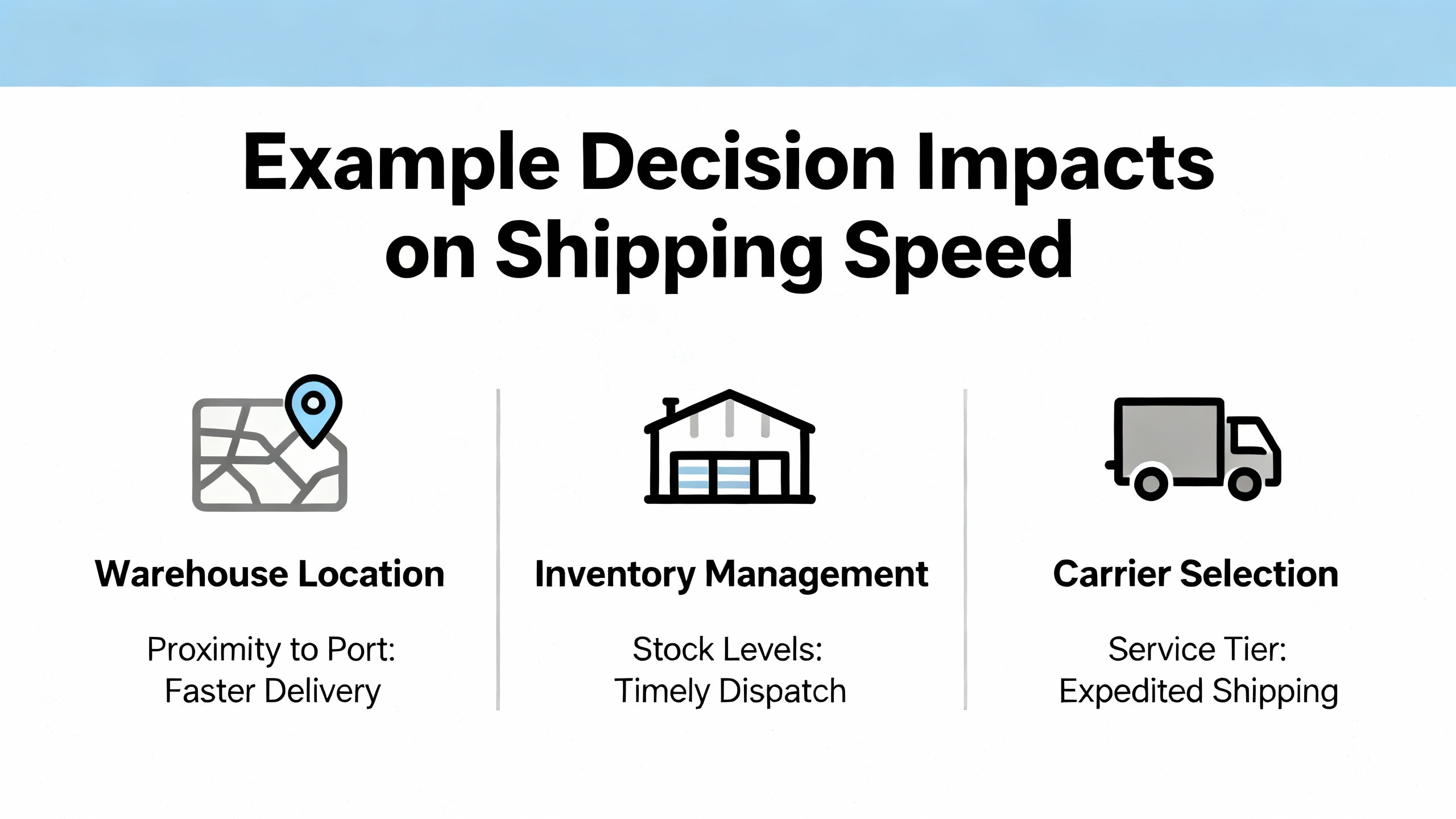

Example Decision Impacts on Shipping Speed

To make these tradeoffs concrete, consider a simplified comparison of three common approaches.

| Approach | Impact on Project Schedule | Shipping and Stocking Implications | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrete, board level DC‑DC design built from separate controllers, FETs, and magnetics | Longer design and validation time; more thermal and layout iteration; more risk of late redesigns if parts change | Many line items to procure; higher risk that one small part delays the full design; more complex stocking for spares | High volume, cost sensitive products where you control the entire lifecycle and have stable demand |

| Integrated DC‑DC power module such as those from TI or similar vendors | Shorter design cycle; validated SOA curves and evaluation boards reduce engineering risk; easier reuse across projects | Single module SKU per rail; easier stocking; modules often carried by multiple distributors with published lead times | Industrial controllers, custom drives, and edge compute where time to market and reliability trump slight component cost savings |

| Rack or chassis level redundant power modules such as CRPS units from FSP or high density modules from Vicor | Very fast integration at system level; redundancy built in; easy scalability by adding modules | Few SKUs to carry; straightforward spares strategy; modules may be heavier and require better freight handling but are robust | Data center style automation islands, large control rooms, and high availability systems needing N plus one redundancy |

The right answer depends on your volume, regulatory environment, and internal expertise, but from a pure fast shipping and reliability standpoint, the middle and right columns usually win for industrial automation projects.

Brief FAQ

How many spare power modules should I keep on site?

There is no single right number, but start by looking at failure history, vendor reliability, and realistic replenishment times. If your logistics and supplier performance give you confidence in two to three day replenishment, you can often keep only a small number of spares per critical module type, sized to cover the worst credible cluster of failures between restocks. For modules with long lead times or limited sources, carry more or redesign toward standardized platforms with better availability.

Are high‑density power modules more fragile to ship?

Not inherently, but they are less forgiving of sloppy handling. Semiconductor Engineering and SemiconductorReview show that modern packages are designed to handle high temperatures and mechanical stress through better materials and structures. However, because they concentrate more power into less space, latent damage has more serious consequences. Using the packaging and electrostatic discharge practices recommended by Polymer Molding and shipping PC power supply guidance minimizes this risk.

Does fast shipping always mean higher shipping cost?

Not if you design for it. Studies on shipping optimization from providers like Next Exit Logistics, ProvisionAI, Sophus, Loop, and others show that right sizing packaging, consolidating loads where appropriate, and using route and mode optimization tools can cut cost even as delivery times improve. In practice, the cost of a faster lane is often far lower than the cost of production downtime caused by a missing module.

Fast shipping of power supply modules is not something you bolt on at the end of a project. It is the outcome of good power architecture choices, robust packaging inside and outside the module, and a logistics network that takes electrical supplies as seriously as finished machines. When you treat power modules as standardized, well engineered building blocks and back them with clear stocking and shipping strategies, you stop talking about “expedited shipping” and start talking about predictable delivery. That is the level of reliability every integrator should bring to the table.

References

- https://www.esgamingpc.com/a-guide-to-choosing-the-right-shipping-method-for-pc-power-supplies.html

- https://gesrepair.com/8-best-practices-for-extending-the-life-of-industrial-power-supplies

- https://www.dispatchtrack.com/blog/logistics-optimization

- https://www.emergemarket.com/post/understanding-logistics-network-optimization-a-shippers-perspective

- https://eszoneo.com/info-detail/shipping-lithium-ion-batteries-ups-guidelines-and-best-practices

- https://www.fsp-ps.de/ru/knowledge-195-Ensuring-Reliable-Power-Supply-for-Data-Centers-Best-Practices-and-Solutions.html

- https://www.loop.com/article/5-keys-to-logistics-network-optimization-success

- https://nextexitlogistics.com/10-tips-to-reduce-shipping-costs-in-logistics-strategies-for-efficiency/

- https://www.polymermolding.com/best-practices-for-shipping-fragile-electronics-securely/

- https://provisionai.com/essential-tips-for-logistics-load-planning-and-optimization/

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment