-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 21500 TDXnet Transient

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

HMI Black Screen Repair: Diagnostic and Resolution Methods

When an HMI goes black in the middle of a shift, the first reaction on the plant floor is often the same: someone calls the panel “dead,” and replacement quotes start flying around. In practice, that is usually the wrong first move. Across production lines and process plants, most black screen events trace back to a relatively small set of root causes that can be diagnosed with straightforward, methodical checks.

Service organizations such as Industrial Automation Co. report that more than a quarter of the “dead” HMIs they receive for repair have simple power issues, not catastrophic hardware failures. Other cases come down to backlight aging, corrupted firmware, damaged touch or digitizer glass, environmental contamination, or even a screen saver bit being driven the wrong way by PLC logic. The difference between a short pause and a long shutdown is knowing how to separate these causes quickly.

This article lays out a practical, field-tested approach to HMI black screen diagnosis and repair. It draws on community experience from vendors and repair houses including Industrial Automation Co., Global Electronic Services, DriveFix Electronics, AutomationDirect’s technical community, Pro-face, Siemens support channels, Maple Systems, MRO Electric, IVS Incorporated, and Beijing STONE Technology. The goal is to take you from “the screen is black” to “root cause identified” with minimum guesswork and maximum repeatability.

What a Black Screen Really Means

“Black screen” is an operator description, not a diagnosis. It can reflect several very different technical situations, and the first job is to understand which broad category you are dealing with.

In the simplest scenario, the entire panel is truly off. There is no backlight glow, no status LEDs, no relay clicks or beeps on power up. That usually points to loss of power, an internal power supply fault, or a protective device such as a fuse or surge protection circuit that has opened. Many industrial HMIs run on 24 VDC, while some legacy units expect 120 VAC. If that input is outside tolerance or unstable, the HMI will often refuse to boot at all.

A more subtle scenario is a panel where the LCD and CPU are active, but the backlight is out or effectively disabled. Industrial Automation Co. recommends a simple flashlight test: shine a bright light across the screen at an angle. If you can see faint menus or graphics, the LCD controller is running and the underlying logic is alive. In that case, the suspects are the backlight, its driver or inverter, brightness settings, or a system register that has commanded the backlight off. Pro-face documentation describes similar behavior when a backlight is near end of life and a burnout detection function responds to increased current draw.

A third scenario involves software, firmware, or operating system problems. Siemens MTP700 Unified Comfort panels, for example, have been observed to show the vendor logo briefly after a site power cut, then remain on a black but backlit screen without loading the normal runtime. The HMI responds to pings but not to engineering tools, a pattern consistent with a corrupted runtime image or file system. Certain ED‑HMI devices showed intermittent black screens after a manual reboot, even though the system continued running and an external HDMI display worked normally; a timing problem in the display driver was eventually identified and corrected through a kernel update.

Finally, not every “black” or “frozen” display is a pure screen issue. If an HMI loses communication with its PLC, tag reads and writes stop. Data may freeze on the last good values, and operator inputs no longer have visible effect. From the operator’s point of view, this often gets reported as a dead or black panel, even though the display and backlight are healthy and the real culprit is the communication link.

The key point is that black screen is a symptom. Before you spend money or time on the wrong fix, you need a simple, repeatable diagnostic path that distinguishes power loss, backlight failure, software corruption, and communication issues.

Start Diagnostics with Power

Power problems are the single most common reason an HMI appears dead. Industrial Automation Co. notes that more than 25% of HMIs returned to them with black screen symptoms are ultimately traced to incorrect voltage, weak power supplies, bad terminals, or blown fuses rather than internal electronics. IVS Incorporated and Beijing STONE Technology report similar patterns in their discussions of display failures.

That is why every serious diagnostic approach begins at the power terminals of the HMI, not in the PLC program.

The first step is to verify the incoming voltage directly at the HMI’s supply terminals with a meter, not just at the power supply output. Many modern panels expect a narrow 24 VDC range. If the voltage sags when large motors or heaters start, or if an aging switch‑mode supply injects heavy ripple, the HMI may reset or fail to boot even though the supply appears acceptable at no load. Some Mitsubishi models can appear completely dead when polarity is reversed or ripple is excessive, even though nothing inside has physically failed.

Next, inspect wiring and connectors feeding the HMI. High ambient temperatures, vibration, and moisture work together to loosen terminal screws, oxidize contacts, and cook insulation. The industrial LCD guidance from Beijing STONE Technology emphasizes verifying that the host power indicator is lit, the power fan is spinning, and the main power switch is actually functioning. It also recommends checking switch and reset buttons for poor-quality contacts that can interrupt power and create intermittent black screen symptoms.

Many HMIs include onboard fuses or detachable power modules. Compare these against the manual and test or replace them where appropriate. A surprising number of blank screens are ultimately traced to low‑cost protection elements that did exactly what they were meant to do during a surge or wiring mishap.

Only after you are satisfied that the HMI sees the correct voltage, with solid connections and intact protective devices, should you treat the device itself as suspect. Skipping this step wastes an enormous amount of field time.

Distinguishing Backlight and Display Failures

Once power is confirmed, the next question is whether the screen is truly off or just invisible.

LED backlights are consumable components. Guides on Siemens panels note that backlights are often rated for tens of thousands of operating hours and will dim, flicker, or develop uniform brightness loss before failing completely. Global Electronic Services describes how time‑dependent backlight degradation gradually reduces readability, while outright failure of the backlight or its driver can leave the screen black even though the LCD is still refreshing in the background.

The flashlight test is a simple but powerful tool. If you can see faint images on the panel under angled light, the LCD and graphics controller are operating. In that case, attention should shift to the backlight, its inverter or driver circuitry, brightness and contrast settings, and any HMI or PLC registers that control display on and off. Pro-face documentation highlights that certain system area addresses can be written with values that command the display or backlight off and that this can result in a black screen even while the application logic continues to run normally.

Status LEDs can provide useful clues as well. On Allen‑Bradley PanelView Plus units, combinations of red and green LED patterns near the SD card slot can indicate memory or bootloader faults. Mitsubishi GOT2000 panels use POWER and STATUS LEDs whose blink patterns correspond to specific problems such as CPU failure or firmware load errors. Pro-face notes that an orange status LED combined with a black display often indicates either insufficient supply voltage or backlight burnout detected by internal monitoring.

In many designs, a true backlight failure behaves differently from a logic‑driven screen saver. Where the backlight hardware is failing, the panel tends to stay dark or gradually worsen, rather than blanking intermittently and immediately waking when touched. That distinction matters when deciding whether to focus on configuration and tags or on hardware replacement.

When you suspect the display hardware itself, temporarily swapping in a known‑good panel of the same type is an effective isolation technique, provided power is fully disconnected and static precautions are observed. If the problem follows the HMI, you have a hardware issue. If it stays with the cabinet, power or wiring is still the likely suspect.

Touch and Digitizer Problems That Masquerade as Screen Failures

Operators often equate an unresponsive touchscreen with a dead display, but the two are not the same. Global Electronic Services and other repair providers separate touch faults from display faults, and that distinction has both diagnostic and financial implications.

Touchscreens fail in several ways. Resistive overlays wear down from constant use, delaminate, or accumulate contamination from dust, oil, and cleaning chemicals. Capacitive surfaces can develop microscopic cracks under thermal stress or impact. The result is ghost touches, dead zones, or inputs that register in the wrong location even while the image itself is sharp and bright.

Before assuming a digitizer failure, it is worth running through basic checks. Confirm that power is stable, reseat loose cables, power cycle the HMI, and visually inspect the surface for obvious cracks or damage. Many HMIs include built‑in calibration tools accessible through a system menu. Following the prompts and touching reference points with a finger or stylus can restore proper alignment when calibration data has drifted.

If the display looks healthy but touch remains erratic or dead after calibration, an external input device can help distinguish hardware from software faults. Global Electronic Services recommends connecting a USB or PS/2 mouse to panels that support it. If you can navigate menus and operate the application with the mouse while touch remains inaccurate or non‑functional, the CPU, operating system, and display chain are likely fine, and the fault lies in the digitizer or its wiring.

A digitizer replacement is usually recommended when touch still works in some areas, when ghost touches occur, or when there is visible physical damage to the front glass but the rest of the HMI operates normally. Full HMI replacement becomes the better option when the entire front end is damaged, when the display is completely black in combination with deeper symptoms such as abnormal noises or smells, or when internal faults clearly extend beyond the touchscreen.

Software, Firmware, and OS‑Level Causes of Black Screens

Modern HMIs are embedded computers, and software or firmware problems can leave them looking black even when the hardware is sound.

One example comes from ED‑HMI devices that can show intermittent black screens after a manual reboot. During the black screen condition, secure shell access remains available and an HDMI‑connected external display works normally, which indicates that the operating system and application continue to run. Investigation traced the issue to a display driver timing problem: the interval between two I²C commands during panel initialization was too short. The vendor resolved this by releasing updated kernel images, and once those images were installed and verified by comparing checksums, the intermittent black screen disappeared.

Siemens MTP700 Unified Comfort panels provide another case study. In a reported failure, the panel displayed the Siemens startup logo after a site power cut, then switched to a black but still backlit screen and never loaded the normal runtime. The HMI responded to pings but could not be reached through the engineering environment, suggesting that the network stack was partly alive while the runtime or operating system was not starting correctly. Siemens’ ProSave utility, which can perform backups, restore images, and execute operating system or factory resets, was identified as the path to recovery.

Configuration tools themselves can also create what looks like a black screen. Maple Systems notes that EBPro, its HMI configuration software, uses OpenGL for rendering and that some PCs exhibit windows with completely black interiors and pop‑up OpenGL errors when graphics drivers are outdated or unsupported. Their recommended troubleshooting steps are to update the computer’s video drivers and, if necessary, switch EBPro to software rendering using a bundled DisplaySetting utility.

Firmware corruption is another path to a blank display. A Solis Service Center guide describes inverters whose LCD HMIs become inaccessible or show a blank screen due to corrupted firmware. Recovery involves inserting a USB flash drive with the correct firmware, entering a bootloader mode using a specific button combination, and triggering the update. Successful updates are indicated through a defined LED pattern.

DriveFix Electronics, in its comprehensive guide to HMI troubleshooting and repair, recommends handling software faults by updating firmware to the latest stable version, reinstalling or restoring software, and using a factory reset only after full backups of existing configurations. The key principle across these examples is that if you can still reach the device over the network, or if external ports and diagnostic modes behave normally, you must consider firmware and software causes before declaring the hardware dead.

Communication Failures Misdiagnosed as Screen Problems

In many plants, any HMI that does not show live, changing data eventually gets labeled as “black” or “hung,” even when the display is technically fine. A common pattern in the literature on HMI troubleshooting and maintenance is that communication failures between the HMI and PLC are often misinterpreted this way.

HMIs rely on continuous communication with the main controller over Ethernet or serial protocols. When this link is broken, tag reads and writes stop. Values can freeze, alarm banners no longer update, and manual jog or teach functions that depend on live data no longer work. From the operator’s point of view, the panel seems unresponsive, and that complaint frequently gets summarized as a screen failure.

For Ethernet‑based systems, one recommended starting point is to run ping tests between the HMI and PLC. Intermittent replies often indicate loose or faulty terminations such as poorly crimped RJ45 connectors. HMI troubleshooting and maintenance guidance suggests re‑crimping and using a meter to confirm continuity on every pin. When cables and terminations test good, software and network causes become more likely. Packet capture tools can uncover duplicate IP addresses, conflicting port usage, and misconfigured network address translation that fails to route traffic correctly.

With serial links, damaged or miswired Profibus, Profinet, RS‑232, or RS‑485 cables, incorrect baud rates, and mismatched protocol settings can all create the impression of a dead HMI. Guides on Siemens and Magelis panels point out that PLC access protections, outdated drivers, and time desynchronization can also prevent valid communication even when physical links are intact.

Firewalls can silently block HMI‑PLC traffic, especially after system or operating system updates. Troubleshooting and maintenance articles emphasize verifying that the required ports for the HMI protocol are allowed and that rules have not changed unexpectedly.

The essential message is that communication should be treated as its own diagnostic branch. If the HMI powers up and shows a screen but does not behave correctly, verify the network and protocol layer before moving on to invasive panel repair.

Intermittent Blackouts, Screen Saver Logic, and Tag Conflicts

Some of the most frustrating black screen problems are intermittent. The screen blanks during production, then wakes when someone taps it, only to fail again later. Panels may pass bench tests yet misbehave on the line. In many C‑more and similar HMI implementations discussed in AutomationDirect’s technical community, the root cause has turned out to be logic rather than failing hardware.

In these designs, the PLC or HMI program drives tags that control the backlight as a form of screen saver. When those tags are modified, or when they are overwritten by unrelated program logic, the backlight can be turned off unexpectedly. A key observation from these discussions is that a true backlight failure is rarely intermittent, while logic issues that affect backlight control bits tend to be.

The practical recommendation is to audit every tag that influences display and backlight behavior. That includes screen saver control bits, visibility tags tied to buttons used to wake the screen, and any HMI or PLC registers that can turn the backlight off. Program modifications that never accounted for these tags are a frequent culprit.

When a spare panel is available, swapping it in while leaving the PLC logic untouched can help isolate the fault. If the new HMI exhibits the same intermittent blanking, the behavior is likely driven by logic rather than by the panel itself.

A Practical Diagnostic Workflow

Different vendors describe troubleshooting in different formats, but the core structure is remarkably consistent. A general five‑step process described in HMI troubleshooting and prevention material can be adapted into a simple workflow that aligns well with experience in the field.

The starting point is to identify and describe the error carefully. That means asking operators what they saw, what the machine was doing, whether any logos or status screens appeared before the black screen, and whether the issue follows power cycles or temperature changes. Global Electronic Services notes that early warning signs such as occasional flicker, intermittent blackouts, or localized loss of touch sensitivity should be treated as diagnostic clues, not as harmless nuisances.

Once the symptom is clearly defined, attention moves to hardware checks. This begins with power: measuring voltage at the HMI terminals, inspecting wiring and connectors, and checking fuses or detachable power modules. From there, the focus shifts to the display chain, using the flashlight test, checking status LEDs, and, where supported, entering offline or configuration modes to run self‑diagnostics and touch calibration. Pro-face, for example, recommends using offline self‑test and touch panel checks to distinguish configuration issues from hardware faults.

The next layer is communication. If power and display appear healthy but the HMI is not updating, simple network tests help verify connectivity. That includes pinging between HMI and PLC, inspecting cables, validating IP addresses or serial parameters, and confirming that firewall rules allow the necessary ports.

Software and firmware checks follow. DriveFix Electronics recommends handling software faults by updating firmware to stable versions, restoring from backups, and using factory resets only after configurations are safely backed up. In cases like the Unified Comfort panel or ED‑HMI devices, the ultimate fix involved reloading the operating system or installing a corrected kernel that addressed a known display bug.

Finally, a good troubleshooting process ends with testing recovery and logging what happened. HMI troubleshooting and prevention guides emphasize that documenting symptoms, actions taken, and resolutions helps resolve recurring incidents more quickly and supports long‑term reliability analysis.

Repair or Replace? Making the Call

Once you know why the screen is black, you still need to choose between repairing the existing unit and replacing it. Several sources converge on similar guidance regarding cost, risk, and turnaround time.

Industrial Automation Co. notes that when the core controller logic is intact but the screen, backlight, or touch module has failed, repair is usually the best option. They report that repairs typically cost about thirty to sixty percent less than purchasing a new unit, can retain existing program data when readable, and often have a turnaround of about five business days. Global Electronic Services and IVS Incorporated likewise highlight the value of specialist repair for screen, backlight, and connector faults.

Amikong’s practical guide to Siemens HMI panels describes cases where replacing a cracked touch glass restores a panel at a small fraction of the price of a new HMI, making component‑level repair attractive when failures are well defined. Repair is especially compelling for legacy or obsolete models where replacements are expensive or difficult to integrate.

Replacement makes more sense when a panel is truly beyond economical repair, when multiple subsystems are failing at once, or when models are obsolete and spare parts are unavailable. Replacement also brings a fresh warranty and can be part of a broader modernization strategy that upgrades protocols, security, and supportability. HMI panel troubleshooting guidance for Allen‑Bradley HMIs recommends considering redundancy and backup HMIs in critical systems to avoid single points of failure.

A simple way to visualize the trade‑offs is shown below.

| Scenario | Preferred Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Isolated backlight, touch, or connector fault | Repair | Lower cost, fast turnaround, preserves existing program and wiring footprint |

| Repeated failures on the same unit | Replace | Likely deeper underlying damage or design limitations |

| Obsolete model with limited spare parts | Replace | Scarce components, opportunity to modernize and standardize |

| Legacy model widely used in the plant | Repair and add a spare | Repairs extend life; a spare reduces downtime on future failures |

| Firmware or OS corruption with intact hardware | Restore or update | Reloading the operating system or firmware resolves the issue without new hardware |

Some facilities adopt a hybrid strategy: they repair the failed unit while also ordering a replacement to keep on the shelf. Industrial Automation Co. notes that this approach limits current downtime while improving resilience against future failures.

HMI troubleshooting and prevention guidance adds a financial rule of thumb: when the expected repair cost rises beyond roughly half the price of a new HMI, replacement should receive serious consideration. The exact threshold depends on how critical the equipment is and how difficult it is to integrate a new model, but it is a practical starting point.

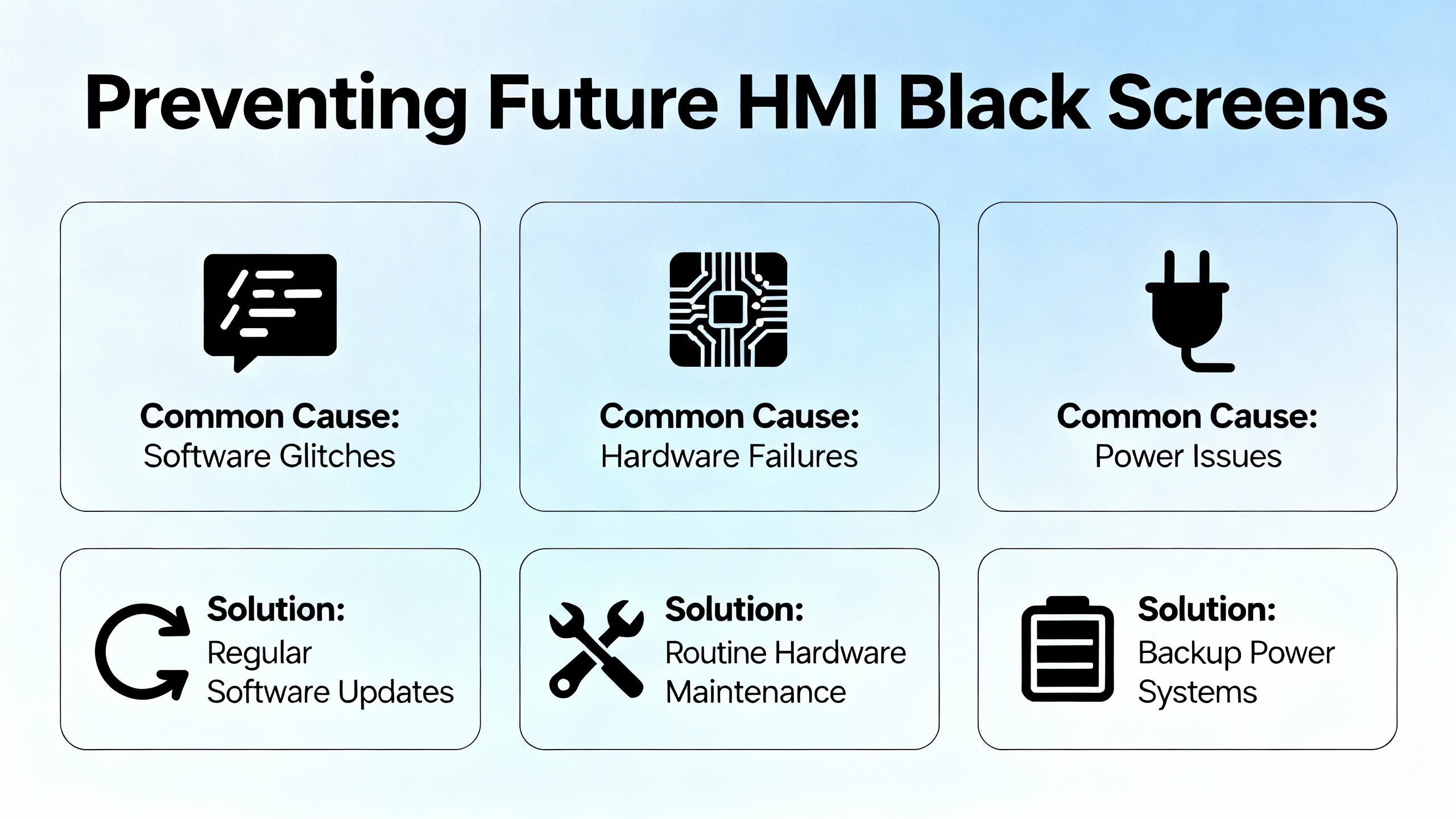

Preventing Future HMI Black Screens

Every hour spent on emergency repair argues for better preventive work. The encouraging news is that preventing HMI black screens depends more on discipline than on exotic technology.

Power quality is the first line of defense. IVS Incorporated emphasizes that incorrect voltage, surges, and unstable power are leading causes of display failures. Using properly sized supplies, installing surge protection, and adding uninterruptible power supplies to critical panels all reduce the risk of brownouts and abrupt shutdowns that corrupt firmware and operating systems.

Environmental protection is equally important. Global Electronic Services describes how dust, oil mist, condensation, and water ingress corrode circuit boards, create false touches, and shorten backlight life. Enclosures with appropriate ratings, intact seals, and routine cleaning with manufacturer‑approved products extend HMI service life. Beijing STONE Technology notes that proper cooling, clear vents, and functioning fans prevent overheating and the solder joint damage that comes with it.

Cabling and connectors deserve regular attention. HMI troubleshooting and maintenance guidance recommends routine monitoring and replacement of communication cables, especially for HMIs mounted on doors or moving equipment where vibration and flexing are constant. Global Electronic Services points out that loose or corroded connectors can cause intermittent flicker and blackouts long before total failure. Systematically tightening terminals, reseating connectors, and replacing damaged cables on a schedule can eliminate many black screen events.

Touchscreen handling habits also matter. Best practice articles recommend using fingers instead of tools, avoiding excessive pressure, and returning portable HMIs to their brackets instead of leaving them in precarious positions where falls are likely. Proper calibration after maintenance and timely replacement of worn overlays keep touch accuracy high and help prevent unresponsive screen complaints that can be mistaken for display faults.

Software governance is another pillar. DriveFix Electronics and MRO Electric stress the importance of regular firmware updates, careful change control on HMI applications, and reliable backups of HMI and PLC configurations. Many black screen incidents linked to firmware bugs or corrupted runtimes could have been avoided or recovered quickly through disciplined update and backup practices. Annual maintenance contracts that include periodic inspections, firmware updates, hardware checks, and structured support coverage can also reduce unplanned downtime.

Finally, operator and maintenance training may be the highest‑leverage preventive measure. IVS Incorporated notes that training staff on proper shutdown procedures, discouraging hard power cuts, and ensuring that early warning signs such as flicker, intermittent blackouts, or localized touch issues are reported promptly can turn potential failures into scheduled service events. Facilities that systematically track these indicators and act while systems are still running are much more likely to avoid unexpected, line‑stopping screen failures.

FAQ

Is a black HMI screen always a dead panel?

No. Field experience and repair statistics show that a significant share of black screen complaints are caused by basic power issues, backlight failures, PLC‑driven screen saver logic, communication problems, or firmware faults rather than destroyed hardware. If status LEDs are active, the unit responds to pings, or faint images are visible under a flashlight, the panel is often recoverable.

What should I check first when an HMI goes black?

The first check should always be power at the HMI terminals. Measure voltage with a meter, inspect wiring and connectors for looseness or heat damage, and look for blown fuses or tripped protection modules. Industrial Automation Co. reports that more than a quarter of panels sent in as “dead” had basic power problems, so confirming power integrity before anything else prevents a lot of wasted effort.

When should I stop troubleshooting and involve a specialist?

If you have verified power, inspected cabling, checked communication settings, attempted reasonable firmware or configuration recovery, and the panel remains black or unstable, it is time to involve a professional repair service or the vendor’s technical support. This is especially important on high‑value or safety‑critical systems. Companies such as Industrial Automation Co., Global Electronic Services, IVS Incorporated, and other industrial repair providers specialize in board‑level diagnostics and can often recover hardware that would otherwise be written off.

References

- https://catsr.vse.gmu.edu/SYST460/HMISequenceDiagrams.pdf

- https://journal.maranatha.edu/index.php/jis/article/view/4710/2398

- https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc845365/m2/1/high_res_d/1082381.pdf

- https://www.plctalk.net/forums/threads/ask-hmi-black-screen-red-lion-crimson-3-0.115333/

- https://www.amikong.com/n/hmi-repair-vs-replacement

- https://www.apterplc.com/blog/hmi-panel-troubleshooting-taking-allen-bradley-as-an-example_b68

- https://library.automationdirect.com/best-practices-effective-hmi-every-time/

- https://drivefixelectronics.com/blog/comprehensive-guide-to-hmi-troubleshooting-and-repair

- https://gesrepair.com/7-common-causes-of-screen-blackouts-and-touch-response-issues/

- https://www.ivsincorporated.com/blog/why-hmi-display-failures-happen-and-how-to-fix-them

Keep your system in play!

Top Media Coverage

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shiping method Return Policy Warranty Policy payment terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2024 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.