-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 21500 TDXnet Transient

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

Network Interface Card Failure Diagnosis in Control Systems

Network interface cards do not get much attention when everything is running well. In a modern control system, though, a single failing NIC on a controller, HMI server, or historian can cascade into stale tags, nuisance alarms, unnecessary failovers, or even full production stops. After years of commissioning and rescuing plants in trouble, I have learned that what looks like a NIC failure almost never starts with the silicon itself. It usually starts with something simpler: a cable under tension, a duplicate IP address, or a driver and firmware combination that has quietly drifted out of support.

This article walks through a pragmatic, field-tested way to diagnose suspected NIC failures in control systems using guidance echoed by HPE Community contributors, Dell, Red Hat, university IT teams, and others. The focus is simple: protect uptime, isolate the true root cause, and only condemn a NIC when the data and tests leave no room for doubt.

What a NIC Really Does in a Control System

A network interface card is the hardware bridge between a device and the rest of your network. As described in networking primers from vendors such as CenturyTech and Fibermall, the NIC lives at the physical and data link layers. It converts host data into frames, adds MAC addressing and error checking, and pushes those frames onto copper or fiber. On the return path, it checks integrity, strips headers, and hands clean data up the stack.

In industrial automation, that simple role becomes critical. NICs on controllers, gateways, and engineering workstations connect to control networks, safety networks, historian and MES backbones, and sometimes to corporate or remote-access networks. These NICs can be:

Wired Ethernet adapters mounted on PCIe slots or integrated on the motherboard of a server or industrial PC, often running at 1 Gbps or 10 Gbps.

Fiber or SFP-based adapters bridging long controller-room runs or routing between control and data centers.

Wireless adapters on laptops and tablets used for field diagnostics and maintenance.

Virtual NICs in hypervisors where virtual HMIs and historians share a physical host.

Across all of these, the NIC’s job is consistent: establish link, transmit and receive frames reliably, and surface error conditions that operations teams can see before a field engineer gets a 3:00 AM call.

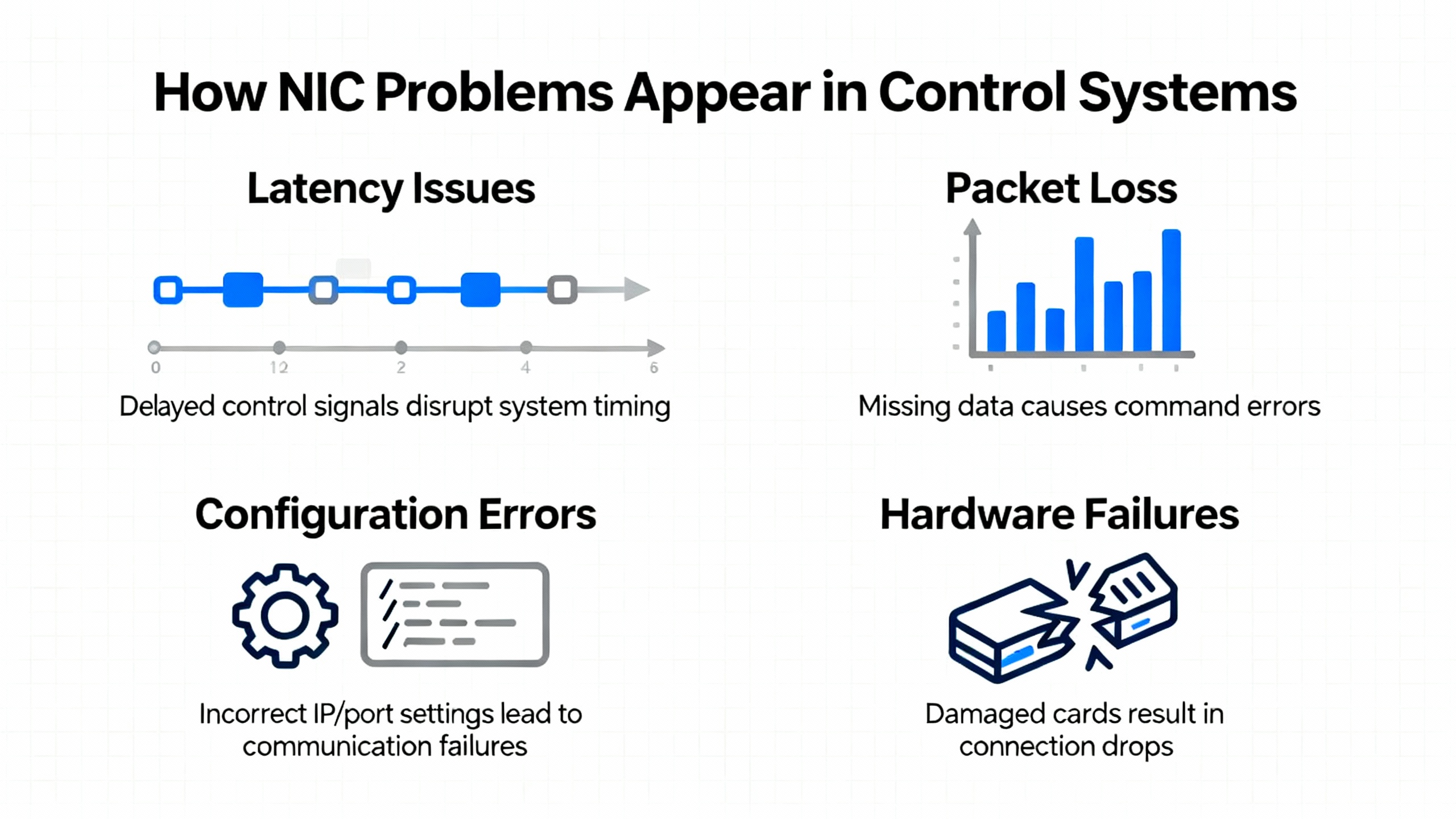

How NIC Problems Show Up in Control Systems

When a NIC or its surrounding ecosystem misbehaves, the symptoms at the control-system layer can be deceptively indirect. Articles from System Observer platforms such as Dynatrace and high-availability vendors like SIOS describe common patterns that align very well with what we see on plant floors.

At the application level you might see slow or sporadic HMI updates even though controllers appear healthy, erratic historian backfills, or batch systems that intermittently fail to receive recipe downloads. In clustered SCADA or HA server environments, SIOS notes that failing or degrading NICs can cause heartbeat packets to drop, leading to false node failures, unnecessary failovers, and even split-brain conditions where two nodes believe they are primary.

On the network side, network interface error references point to CRC errors, runts, giants, and encapsulation errors accumulating silently until they manifest as visible packet loss and full outages. Dynatrace emphasizes that TCP/IP stacks are resilient and will mask a lot of underlying errors through retransmissions and congestion control. The user sees “slow network” or “sticky HMI,” while the NIC counters quietly show checksum errors, dropped packets, and retransmissions.

A key principle from Unix administrators and hardware specialists is worth repeating: Ethernet NIC hardware “almost never” fails outright. Most issues that look like NIC failures start with bad or stressed cables, marginal connectors, misconfigured ports, or IP conflicts. That principle should guide how you approach every troubleshooting session.

First Question: Is It Really the NIC?

Before you open a control cabinet or schedule downtime on a controller, answer the scope-of-impact question. Several Windows support articles and university IT guides stress this step.

If multiple automation devices across the same network segment lose connectivity at once, the problem is unlikely to be a single NIC. It is more likely a switch, router, firewall, or external uplink. Microsoft’s guidance for Windows PCs also points out that Ethernet and Wi‑Fi typically use different network adapters. When both wired and wireless connectivity fail at the same time on one machine but other devices still work, you should suspect something above the NICs, such as a router or system configuration issue, rather than simultaneous NIC failures.

If other devices in the same cell or on the same infrastructure are healthy, but a particular HMI, historian server, or controller appears isolated, then it becomes reasonable to look more closely at that node’s NIC and network stack.

Basic network troubleshooting practice from educational sources recommends this early set of checks on the affected node:

Check whether a browser can reach multiple external sites, not just a single vendor portal or cloud endpoint, to distinguish a general connectivity problem from a remote-server outage.

Use ping to test connectivity step by step: first the local loopback address, then the device’s own IP, then its default gateway, and finally known external IP addresses. This separates local NIC and stack issues from routing or DNS problems.

Inspect the device’s IP configuration using ipconfig on Windows or ifconfig / ip a on Unix-like systems. If the address sits in an Automatic Private IP Addressing range such as 169.254.x.x, it indicates the device failed to obtain a proper address from DHCP, which could be a configuration, network, or driver issue rather than a bad NIC.

Only after those basic scope checks should you start treating the NIC itself as a primary suspect.

Physical Layer: Cables, Ports, LEDs, and Modules

Once you are confident the issue is isolated to a specific node or link, start where hardware engineers and Dell’s PowerEdge troubleshooting guidance start: the physical layer.

On copper RJ45 cards, Dell notes that you can treat them as relatively simple devices. Link LEDs are typically positioned near the top of the connector. One LED indicates link and speed, and the other indicates power and blinks with activity. ComputerHope highlights similar behavior: a solid green light usually means link and a flashing light indicates data transmission, while no light or an error color suggests a cabling, port, or signal problem.

In control cabinets where the NIC port is accessible, take these steps before touching drivers or configuration:

Verify the patch cable is firmly seated in both the NIC and the switch. Reseating both ends forces a fresh autonegotiation and often clears marginal contact issues.

Swap in a known-good cable and, if possible, move to a different switch port that is administratively up. Guidance from IT teams and Dell alike stresses that switch-port failures and open cables are common and can perfectly mimic NIC faults.

If the machine has multiple ports on the same NIC, compare LEDs and link status across them. When all ports on the card are dark with known-good cabling and ports, the probability of a card-level fault increases.

Dell and SIOS both emphasize physical inspection. Look for bent blades in RJ45 jacks, scorch marks, or signs of overheating around the NIC. Unusual heat or visible damage is a strong indicator that you should schedule replacement rather than extended software troubleshooting.

For fiber and SFP-based NICs commonly used on longer links between control rooms and data centers, Dell’s documentation calls out several additional checks. An SFP-based port cannot function without a suitable Direct Attach Cable or SFP module plus fiber. Confirm that the SFP is fully latched into the port, the fiber or DAC is connected, and the port LEDs show link. If the SFP and cable are present but LEDs stay dark, it is important to verify that the corresponding switch port is enabled and that the optics and cables are part of an approved compatibility set; many first‑time link failures turn out to be unsupported module combinations rather than defective NICs.

Red Hat’s case study on a Linux server using NIC teaming illustrates just how subtle a physical issue can be. In that example, a slightly stretched Ethernet cable caused one member interface of a team to flap up and down every few seconds. The team device continued to function on the healthy interface, so basic reachability tests looked fine. Only by checking link state with ethtool, counting repeated link-down events in teamdctl, and correlating with kernel logs did the administrator trace the issue back to the stressed cable. In a redundant control system, that is exactly the kind of silent degradation that can derail failover behavior if left undetected.

The practical message for control environments is straightforward. Treat every NIC diagnosis as a cabling and port investigation first. Only when you have ruled out cables, ports, SFPs, and obvious physical damage is it time to move deeper into the stack.

IP Addressing, Conflicts, and Misconfiguration

With link and physical health confirmed, the next failure class is addressing and configuration. The University of Oregon’s connectivity guide and an HPE Community post by consultant Steven E Protter both underline how often IP issues masquerade as NIC failures.

IP conflicts are a classic example. In the HPE Community discussion on HP‑UX servers, Protter notes that the first suspected cause for sudden network loss should be an IP address conflict, not a NIC fault. A simple field test is to disconnect the suspect server from the LAN and then ping its configured IP address from another host. If you still get replies, another device has come up using that same IP. In control systems, where static addressing is common and documentation can lag reality, a newly added engineering laptop, controller, or vendor box reusing an old IP can easily take out a critical node.

The HP‑UX case also surfaces a subtle configuration trap: that platform does not support two NICs in the same server configured on the same IP subnet. When another NIC on the same segment is inadvertently brought up, the host can drop off the network immediately. Protter points out that hidden scripts or administrative tools may have enabled the second interface without operators realizing it. The underlying lesson extends well beyond HP‑UX. On any control-system host, especially with multiple onboard NICs or virtual adapters, be very cautious about multi-homing a device on the same subnet and always inventory which interfaces are truly active.

Invalid or fallback addresses tell a different story. The University of Oregon guidance explains that addresses in private ranges assigned by the router, along with valid gateway and DNS entries, indicate basic IP configuration is working. Addresses in special ranges such as the 169.254 block, often associated with Automatic Private IP Addressing, signal that the device could not get an address from DHCP. At that point, the likely culprits are DHCP configuration, intervening network devices, or local driver and stack issues, not the NIC hardware.

Proxies and security software complicate the picture further. That same university guidance emphasizes checking for unwanted proxy settings injected by spyware or misconfigured tools, as well as testing in safe modes or with security suites temporarily relaxed. In control systems, where outbound access is often tightly filtered and vendor tools may install their own components, it becomes easy to misdiagnose proxy or firewall behavior as a failing NIC if you skip this step.

In practice, you should treat IP addressing and basic network settings as a dedicated phase of NIC diagnosis. Confirm whether DHCP is expected or static addressing is the standard. Compare the suspect node’s configuration with a known-good peer. Only when the addressing and gateway details are unquestionably correct should you look more deeply at drivers and the network stack.

Operating System, Drivers, and Network Stack Health

Once physical and configuration issues have been cleared, it becomes appropriate to question the software side of the NIC. Multiple Microsoft support threads, university IT articles, and vendor documentation converge on a common flow for Windows systems, which are still prevalent in industrial HMIs, historians, and engineering workstations.

A practical Windows sequence usually starts with running the built‑in Network Adapter troubleshooter, accessible via the classic Control Panel troubleshooting interface. This tool automatically examines common adapter and connectivity issues and applies simple fixes. While it will not solve deep driver or hardware problems, it is a low‑risk first pass that can save time.

If problems persist, Microsoft and university teams recommend moving to Device Manager. Expand the Network Adapters section and inspect each adapter for warning icons. Missing devices, red crosses, or yellow exclamation marks indicate driver issues or disabled hardware. From there, updating the driver, or uninstalling and rebooting to force a fresh driver installation, often resolves compatibility issues. When automatic updates fail, the explicit advice is to obtain the latest driver from the NIC or system manufacturer.

On Windows, advanced recovery steps revolve around resetting core networking components. Support articles detail a series of administrative commands run from an elevated Command Prompt: resetting the TCP/IP stack, resetting Winsock, releasing and renewing IP information, and flushing DNS. The goal of this sequence is to clear corrupted or misconfigured stack components that can block connectivity even when the NIC hardware and link are functioning.

The University of Oregon article also reminds administrators to verify that IPv4 settings are correct, particularly whether adapters are set to obtain addresses automatically when that is expected, or to use proper manual settings if the environment relies on static configurations. Misaligned DNS settings can show up as “network failures” even though IP connectivity is fine, which is why ping tests to known IPs remain important in parallel with these stack resets.

On Unix-like systems, including Linux control servers, historians, and industrial PCs, the diagnostic toolkit looks different but serves the same purpose. The ifconfig or ip a commands verify interface state, IP configuration, and error counters. The ethtool command, highlighted both in Unix Stack Exchange discussions and SIOS documentation, provides link speed, duplex, supported and advertised modes, and a simple “Link detected” status that quickly answers whether the NIC sees physical connectivity. ethtool -S can expose detailed per‑counter statistics that help distinguish between physical issues and higher‑layer problems. Kernel diagnostics from dmesg and system logs accessed through journalctl complement this view, surfacing driver resets, link-down events, and other NIC-related messages over time.

HP‑UX administrators, according to HPE Community contributors, rely on platform-specific tools such as cstm, mstm, or the graphical xstm to exercise NIC hardware. These tools can mark a failing card visually and support continuous exercise tests, with repeated failure indicating a card that should be replaced. HPE also stresses staying current on OS patches and hardware enablement bundles, since outdated drivers and firmware frequently show up as intermittent NIC problems.

The overarching best practice across platforms is consistent. Before condemning a NIC, use the operating system’s native tools to verify that the driver is loaded, the interface is up, the stack is functioning, and the OS is not logging recurrent errors about that device. Only when all of those software-level checks are clean and the symptoms remain should your suspicion pivot back to hardware.

Making Sense of NIC Statistics and Errors

NICs and operating systems collect a wealth of statistics that can move your troubleshooting from guesswork to evidence-based diagnosis. References from Dynatrace, Exam Labs, Unix administrators, and others give a very practical framework.

Commands such as ifconfig, netstat -e, and netstat -s on Windows or Unix-like systems present aggregate counts of packets received and sent, discards, errors, retransmissions, and protocol-specific events. For example, netstat -s can reveal how many TCP segments had to be retransmitted, how many IPv4 datagrams failed fragmentation, or how many ICMP messages were generated. The Dynamically typed network-operations guidance suggests that while TCP retransmissions are expected occasionally, sustained elevated retransmission rates can indicate congestion or underlying path problems that deserve attention.

At the NIC level, ethtool -S exposes counters like collisions, late collisions, aborted frames, receive FIFO overflows, jabber, and FCS errors. The Unix Stack Exchange guidance underscores that on a healthy full‑duplex link, these error counters should be essentially zero. Non‑zero values, especially growing ones, often point to physical problems, duplex mismatches, or faulty hardware.

Exam-oriented resources on network interface errors describe several specific error types that show up in these counters. CRC errors occur when the cyclic redundancy check on a frame fails, typically due to electromagnetic interference, bad cabling, or failing hardware, and lead to retransmissions and reduced throughput. Runts, or undersized frames, often indicate collisions or misconfiguration on busy segments. Giants, or oversized frames, suggest mismatched MTU settings or faulty devices, and encapsulation errors point to incompatible or incorrectly configured protocols between devices.

To make these concepts more concrete, the following table summarizes error categories and what they suggest.

| Error or metric | What it indicates | Typical causes |

|---|---|---|

| CRC errors | Frames fail integrity checks and are dropped | Electromagnetic interference, damaged cables or connectors, failing NIC or port |

| Runts | Frames smaller than the minimum Ethernet size | Collisions on shared media, duplex mismatches, misconfigured segments |

| Giants | Frames larger than the configured maximum | MTU or VLAN tagging mismatches, faulty devices |

| Encapsulation errors | Packets arrive in an unexpected encapsulation format | Protocol mismatches, misconfigured trunks or tunnels |

| Collisions / late collisions | Contention or duplex problems on a link | Half‑duplex misconfiguration, overloaded legacy segments |

| TCP retransmissions | Segments resent because acknowledgments were not received | Congestion, path issues, or underlying physical errors |

These counters are especially valuable in control systems where you often cannot freely experiment on production networks. By sampling statistics over time, you can see whether error rates spike during specific shifts, after scheduled work in a cabinet, or when certain loads come online. Monitoring platforms and SNMP-based tools can alert on threshold crossings, such as a sudden jump in CRC errors on a controller uplink, providing early warning before operations see an impact.

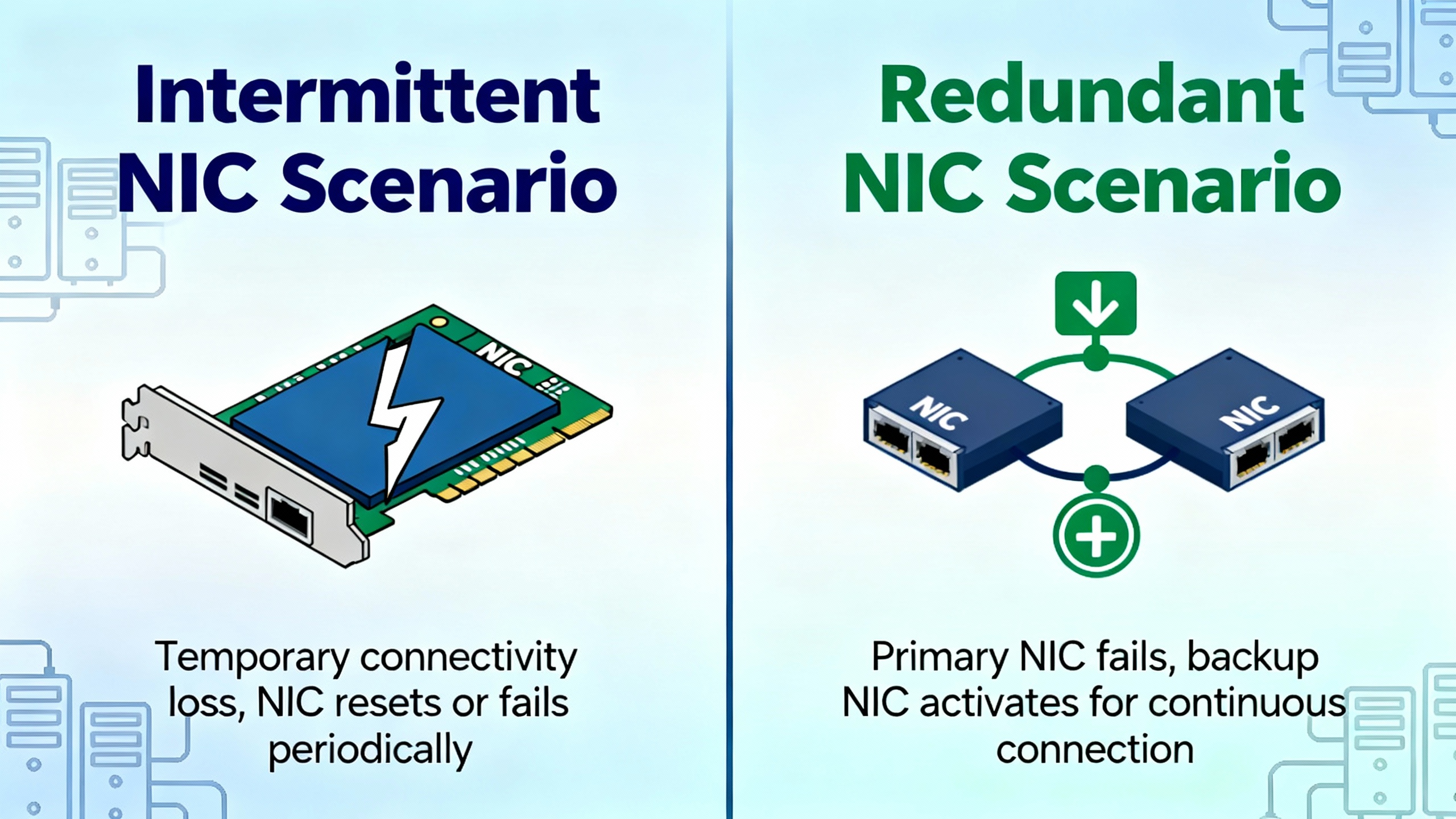

Intermittent and Redundant NIC Scenarios

The most dangerous NIC issues in an automated plant are the intermittent ones. A NIC that fails hard and stays down is inconvenient, but a NIC that flaps in and out of service or silently degrades can upset high‑availability designs and control loops.

Red Hat’s story about NIC teaming under Linux illustrates this challenge. In that environment, the server used link aggregation with two NICs for redundancy and throughput. When one member interface began flapping due to a stressed cable, the logical team kept operating on the healthy member. From the outside, the server still responded, but the down count on the bad interface climbed into the thousands, and logs recorded constant “link up” and “link down” events every few seconds. Without monitoring per-member link state and down-count metrics, such a problem in a control cluster could lurk until a failover occurs at the worst possible moment.

SIOS adds another dimension in clustered environments. There, a NIC that no longer operates at its rated speed can cause slow replication and delayed heartbeat communication. A card behaving like a lower-speed link without clear errors may extend recovery times and increase the risk of data inconsistencies during failover. System logs showing repeated “link down,” “NIC reset,” or “device not responding” messages are strong indicators of this kind of degradation.

In practice, intermittent or redundant NIC issues in control systems call for three disciplines. First, monitor link state, error counts, and down counts on individual interfaces, not just on the logical team or bond. Second, review system logs regularly or with targeted searches for error, warning, and fail keywords related to network devices. Third, perform controlled failovers and link pulls during maintenance windows to validate that monitoring, alerting, and HA behavior match your design assumptions.

These steps take time, but they are far cheaper than discovering a flapping NIC only after an unexplained failover or a control application freeze.

Proving the NIC Is Bad: Isolation and Replacement

Eventually you reach a point where cabling, configuration, drivers, and stack health checks suggest that the NIC itself may be faulty. Multiple sources converge on a single principle at this stage: do not guess; prove it.

One straightforward tactic recommended by Dell and echoed in HPE discussions is to move the cable from the suspect NIC to another available NIC on the same host, then configure that interface with the original address and settings. If the problem disappears, and the original NIC consistently fails when re‑used, the evidence strongly favors a hardware issue. If the problem follows the cable or remains even with a different card, the root cause lies elsewhere in the network or configuration.

TechNow’s step‑by‑step guide and Microsoft community advice introduce another pattern, especially useful on workstations and laptops: testing with an external adapter. Plug in a known‑good USB Ethernet or Wi‑Fi adapter, install drivers if needed, and bring it onto the same network. If connectivity immediately stabilizes with the external adapter, but remains unreliable or absent on the built‑in NIC, the internal interface is very likely defective.

High‑availability guides from SIOS suggest moving a suspect NIC to another system where possible. If a card shows the same errors and behaviors on a different host, that repeatability is a powerful confirmation of hardware failure.

Community responses on platforms like Quora stress a pragmatic conclusion: in most cases, you do not repair a failed NIC, you replace it. Cards are treated as commodity items, from low‑cost adapters suitable for noncritical endpoints up to higher‑end models used in enterprise servers. For integrated NICs on motherboards, the usual approach is to add a discrete PCIe adapter rather than attempt board-level repair, unless the hardware is proprietary and irreplaceable.

Several sources highlight that NIC lifetime is highly dependent on workload, cooling, and power quality. One LinkedIn analysis of Ethernet card performance notes that high‑quality cards can run reliably for many years, but heavy workloads, poor cooling, and power fluctuations can bring performance problems forward. That same analysis estimates that failing NICs are responsible for a meaningful fraction of network slowdowns, and that replacing a suspect adapter with a known‑good NIC is the definitive way to distinguish a card fault from motherboard or broader infrastructure issues.

In control systems, where downtime windows are expensive and tightly controlled, this all points to a replacement strategy focused on clear evidence. Keep a small inventory of compatible spare NICs for your core server platforms. When the data points to a card fault, swap it under a planned change, verify stability with targeted tests, and then retire the suspect card so it does not find its way back into production by accident.

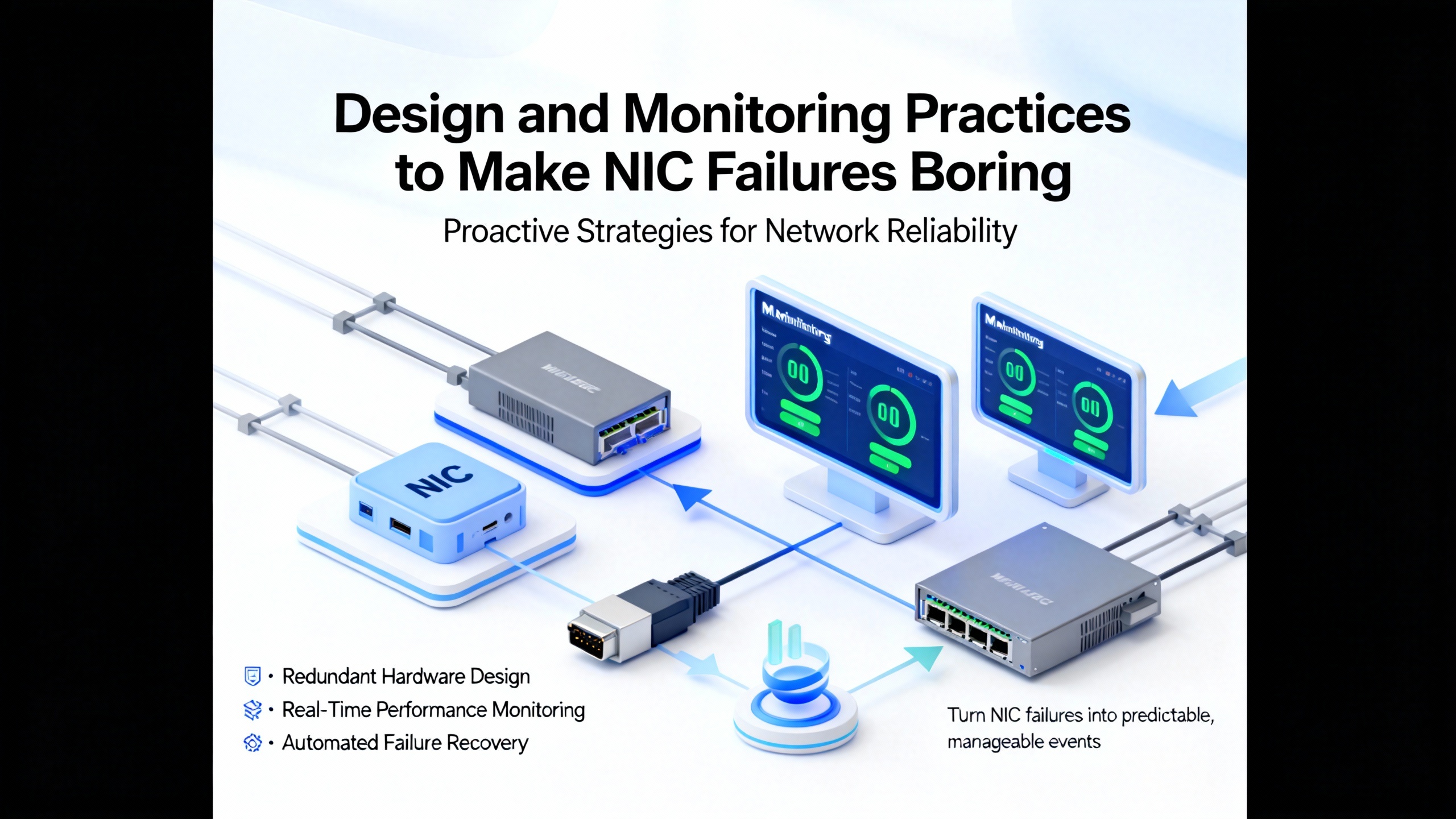

Design and Monitoring Practices to Make NIC Failures Boring

While this article focuses on diagnosis, the most experienced operations teams aim for a simpler goal: making NIC failures uneventful. The sources cited earlier suggest several practices that translate well into industrial environments.

First, implement NIC redundancy thoughtfully on critical servers and gateways. Red Hat’s teaming examples with logical devices dedicated to data and storage traffic show how link aggregation can deliver both additional bandwidth and fault tolerance. In control systems, similar bonding or teaming of NICs for HMIs, historians, and application servers can turn a single NIC failure into a non-event, provided the design is tested and monitored.

Second, treat NIC metrics and interface errors as strategic telemetry rather than obscure counters. Exam-focused resources and monitoring vendors show how interface errors, retransmissions, and queue drops can be trended and alarmed. Establish baselines for each critical link under normal conditions and configure alerts for significant deviations, such as sudden jumps in CRC errors or retransmission rates.

Third, keep drivers and firmware current within the constraints of your validation processes. HPE’s emphasis on hardware enablement bundles and OS patch levels, and SIOS’s reminder that outdated drivers can produce subtle NIC issues, are relevant even in conservative industrial environments. Use a test environment where possible, qualify updates with vendor support, and roll them into production during well-controlled maintenance windows.

Fourth, document and review IP addressing and adapter roles thoroughly. The IP conflict stories from HP‑UX servers, combined with university advice on DHCP and static settings, illustrate how gaps in documentation lead to avoidable downtime. For each critical node, maintain a clear record of which NICs are active, what networks they belong to, and whether they are part of bonds, teams, or redundancy groups.

Finally, remember that NIC failures and near failures are valuable learning opportunities. When an incident occurs, perform a root cause analysis that looks at physical conditions, configuration drift, historical metrics, and monitoring coverage. Red Hat’s example of tracking a flapping link back to a rack movement, and then reflecting on how to monitor redundant components more effectively, is exactly the mindset that hardens a control system over time.

Short FAQ

Can I repair a failing NIC instead of replacing it?

In practice, and as noted by practitioners discussing NIC failures, you generally treat network cards as replaceable components rather than field-repairable devices. For discrete cards, this means swapping in a compatible PCIe adapter. For onboard NICs, adding an expansion card is usually more practical than attempting motherboard repairs. The exception is niche systems where proprietary hardware cannot be easily replaced, but even there, the preference is to add rather than repair where possible.

How often do NICs actually fail in industrial environments?

Multiple Unix and networking discussions emphasize that Ethernet NIC hardware fails much less often than operators think. Most “NIC failures” turn out to be cables, connectors, power, or configuration issues. That said, one industry analysis on Ethernet adapters attributes a noticeable share of network performance problems to failing cards, especially under high heat or power stress. The safest approach is to assume the NIC is innocent until a methodical process rules out simpler causes and repeatable tests point directly at the adapter.

What is the fastest way to tell if my problem is local to one node or systemic?

The quickest approach, echoed across university and vendor troubleshooting documents, is to combine targeted ping tests and cross-device checks. See whether other devices on the same control network can reach the same gateways and external endpoints. If they can, and only one node has issues, dig into that node’s NIC and stack. If multiple devices fail in similar ways, suspect shared network equipment or upstream links instead. That high-level scoping exercise saves significant time before you ever open a cabinet or touch a driver.

Closing Thoughts

In industrial automation, a NIC is not just a port on the back of a box; it is part of the nervous system connecting controllers, servers, and operators. From my perspective as a systems integrator, the most reliable plants are not the ones that never see NIC problems. They are the ones where a NIC issue, when it does arise, is diagnosed calmly with the right tools, confirmed with evidence, and resolved with a simple cable swap or card replacement instead of a frantic all-hands outage. If you build that mindset and monitoring into your control systems, NIC failures become just another routine maintenance task rather than a production‑stopping surprise.

References

- https://software.internet2.edu/ndt/ndt-cookbook.pdf

- https://gautam.engr.tamu.edu/papers/naveen_ierc.pdf

- https://verso.uidaho.edu/view/pdfCoverPage?instCode=01ALLIANCE_UID&filePid=13308585060001851&download=true

- https://www.imss.caltech.edu/services/wired-wireless-remote-access/trouble-shooting--tips

- https://iopn.library.illinois.edu/pressbooks/demystifyingtechnology/back-matter/network-troubleshooting/

- https://service.uoregon.edu/TDClient/2030/Portal/KB/ArticleDet?ID=31787

- https://www.centurytech.sg/understanding-network-interface-cards-nic/

- https://www.computerhope.com/issues/ch000445.htm

- https://www.exam-labs.com/blog/understanding-network-interface-errors-and-system-alerts

- https://www.fibermall.com/blog/network-card.htm?srsltid=AfmBOoo1kLBg1lv6weHAPVpJrrUdCwRylLt4P9Z1d8rAl_Tciw509_jQ

Keep your system in play!

Top Media Coverage

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shiping method Return Policy Warranty Policy payment terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2024 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.