-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Safety-Rated SIL3 PLCs for Hazardous Areas: A Veteran Integrator’s Guide

When you mix programmable logic controllers with flammable gas, vapor, or dust, the room for error disappears. As a systems integrator, I have seen plants spend millions on beautiful mechanical design, only to run hazardous-area safety through a standard PLC input and a couple of relays. They usually get away with it, right up until they do not. Safety-rated, SIL3-certified PLCs paired with the right hazardous-area protections exist precisely to avoid that scenario.

This article walks through how safety PLCs and intrinsically safe designs come together in hazardous areas, what SIL3 really means in practice, and how to decide when the added cost and complexity are justified. I will reference well-established guidance from sources such as Industrial Automation Co., Control.com, Electrical Engineering Resource, Intrinsically Safe Store, Venus Automation, and others, but I will keep the focus on pragmatic design decisions you can use on your next project.

From Standard PLCs to Safety-Rated Controllers

A standard PLC is built to move product, not to save lives. As Industrial Automation Co. and Maple Systems describe, a conventional PLC runs an embedded operating system, scans inputs, executes logic, and drives outputs to keep motors, valves, and pumps on schedule. It cares about throughput, sequence control, and integration with HMIs, variable-frequency drives, and plant networks.

A safety PLC starts from a different premise. As Control.com and Electrical Engineering Resource emphasize, a safety PLC is designed and certified specifically for safety-related functions. It must enforce that a machine or process moves to a safe state when faults or hazards occur, and it must do so with a quantified, very low probability of dangerous failure. Where a standard PLC is judged on uptime and flexibility, a safety PLC is judged on how reliably it can shut things down.

To earn that label, a safety PLC is engineered and assessed against functional safety standards such as IEC 61508, IEC 62061, and ISO 13849. According to these references, certified safety PLC families are rated for Safety Integrity Levels (SIL 1 through SIL 3) or Performance Levels (PL a through PL e). Third-party certifiers such as TÜV Rheinland or Exida evaluate the hardware architecture, diagnostics, and software environment to confirm that the device as used can truly deliver the claimed safety performance.

In practical terms, a modern safety PLC does three extra things compared with a standard unit. It uses redundant processors and safety I/O that continuously cross-check each other, it runs extensive built-in self-diagnostics, and it enforces fail-safe behavior, meaning outputs drop to a safe state on detected faults, power loss, or communication loss. As Electrical Engineering Resource notes, that redundancy and diagnostic coverage allow one device to handle both safety and basic process control in many panels, while still meeting formal safety targets.

What SIL3 Actually Means

SIL is not a marketing badge; it is a numeric risk target. IEC 61508 defines Safety Integrity Levels based on the probability of dangerous failure per hour (PFH) for high-demand or continuous operation. Control.com’s discussion of safety PLCs cites typical ranges for these bands. For high-demand systems, SIL2 corresponds roughly to a dangerous failure probability between about 1×10⁻⁷ and 1×10⁻⁶ per hour. SIL3 tightens that by an order of magnitude, to roughly 1×10⁻⁸ to 1×10⁻⁷ per hour.

To put that in everyday language, SIL3 says that, statistically, dangerous failures of the implemented safety function must be exceedingly rare over the entire operating life. Reaching that band is not possible with a simple single-channel controller and a pair of dry contacts. You need redundant channels, aggressive diagnostics, and a well-defined proof-test strategy so that latent faults are exposed before they line up into an accident.

Performance Levels (PL) from ISO 13849 fill a similar role, especially for machinery. PL e is typically associated with architectures and reliability that are broadly comparable to SIL3 for many practical purposes. Venus Automation and other sources highlight that many safety PLC platforms used in machinery are certified up to SIL3 and PL e when correctly applied.

The key point is that SIL3 is never a property of the PLC alone. It is a property of a complete safety function: input devices, logic, and outputs, including field wiring, power, and proof-testing intervals. The PLC can be SIL3-capable, but the system only achieves SIL3 if every element meets the necessary reliability and diagnostic assumptions documented in the safety manuals.

A Quick View of SIL and Failure Targets

The following table summarizes the ranges cited in the research for continuous or high-demand modes.

| Level | Typical PFH band (IEC 61508 high demand) | Typical applications described in sources |

|---|---|---|

| SIL2 | About 1×10⁻⁷ to 1×10⁻⁶ per hour | Standard process safety systems, many machines |

| SIL3 | About 1×10⁻⁸ to 1×10⁻⁷ per hour | High-hazard process and machinery protection |

Values and context follow the figures referenced by Control.com and DO Supply. SIL1 and SIL4 are defined in IEC 61508 as well, but the articles summarized here focus on SIL2 and SIL3.

Hazardous Areas and Intrinsically Safe PLCs

A SIL3 safety PLC addresses functional safety, but hazardous-area applications add another dimension: explosion protection. Intrinsically Safe Store describes intrinsically safe (IS) PLCs as controllers engineered so that their electrical and thermal energy can never ignite explosive gases, vapors, or dust, even under fault conditions. Instead of containing an explosion in a heavy flameproof enclosure, an intrinsically safe design keeps energy levels below the ignition threshold in the first place.

Hazardous areas are divided into zones or classes based on how often explosive atmospheres are present. Intrinsically Safe Store notes that Zones 0 and 20 represent continuous or long-term risk, Zones 1 and 21 represent likely but intermittent risk, and Zones 2 and 22 represent infrequent risk. In North American terminology, NEC 500 and 505 define comparable Class and Division or Zone systems. For the highest-risk Zones 0 and 20, Ex ia equipment is required. For Zones 1 and 21, Ex ib may be acceptable, and for Zones 2 and 22, Ex ic is often sufficient, provided the detailed rules and certificates are followed.

Intrinsically safe PLCs achieve this with energy-limiting circuitry, such as zener barriers, resistors, and galvanic isolation, paired with modular IS I/O and extensive diagnostics. Even in the presence of short circuits or hot-swapped modules, they are designed so the combination of voltage, current, and thermal behavior cannot ignite the surrounding atmosphere. Certifications and markings to look for include ATEX Ex ia for European explosive-atmosphere compliance, IECEx and UKEX for international recognition, and UL913 or FM approvals for North American intrinsic safety. Temperature classes T1 through T6 are also critical, since they limit the maximum surface temperature to keep it below the auto-ignition temperature of the local gases or dusts.

Compared with flameproof Ex d approaches, which contain an internal explosion within a rugged enclosure, intrinsically safe PLCs and I/O eliminate the explosion source entirely. Intrinsically Safe Store emphasizes that IS designs are lighter, easier to install, and much simpler to maintain, because you do not have to purge and re-certify heavy enclosures every time you open them for service.

One important point the Intrinsically Safe Store guidance stresses is that you should never try to “retrofit” a standard PLC to be intrinsically safe with ad hoc barriers and paperwork. Intrinsic safety is a complete design approach backed by specific hardware, layout rules, and certifications. Using uncertified hardware in a hazardous area creates serious compliance gaps and safety risks.

Safety PLC vs Standard PLC vs Intrinsically Safe PLC

Pulling together the distinctions described by Industrial Automation Co., PLC Department, Plowtech, and Intrinsically Safe Store, you can think of three broad controller categories.

| Controller type | Primary role | Typical standards and certifications | Where it is used according to sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard PLC | General automation and control | IEC 61131-3 for programming, basic UL/CE, no SIL/PL or Ex by default | Packaging lines, material handling, non-hazardous areas |

| Safety PLC | Functional safety for machinery and processes | IEC 61508, IEC 62061, ISO 13849; SIL 1–3, PL a–e; UL and TÜV approvals | Emergency stops, guarding, process shutdown systems in general industrial environments |

| Intrinsically safe PLC | Hazardous-area operation without ignition risk | ATEX Ex ia/ib/ic, IECEx, UL913/FM; coupled with any SIL/PL ratings | Oil and gas, chemicals, mining, pharmaceuticals in Zones 0/1/2 or 20/21/22 |

In many projects, you combine these roles. For example, a SIL3 safety PLC located in a safe area might connect to field devices in a hazardous zone through certified intrinsically safe barriers and IS-rated sensors. In other cases, an intrinsically safe PLC such as the BEKA Pageant controller described by Intrinsically Safe Store may sit directly in a Zone 1 location and implement local logic, while participating in a larger safety architecture.

The key takeaway is that neither SIL3 nor intrinsic safety is sufficient alone. In a hazardous area you must meet both the functional safety target (SIL or PL) and the explosion-protection requirements (ATEX, IECEx, NEC classifications). Every controller and field device in the safety loop must carry the right combination of approvals.

Inside a SIL3 Safety PLC: How It Fails Safe

Control.com and Electrical Engineering Resource describe how safety PLCs are built from the ground up to detect faults and respond safely rather than continuing operation blindly. Several architectural features matter when you aim for SIL3.

Redundant processing and dual-channel I/O are the backbone. Safety PLCs typically contain two or more processors running the same safety logic in parallel. The outputs from these processors are continuously compared; any mismatch triggers a controlled move to the safe state. Safety input modules often accept dual-channel signals from devices like emergency stops, guard switches, and light curtains, and they monitor correlation between channels to detect shorts, cross-wiring, or contact welding. Plowtech notes that some platforms implement the redundancy in hardware with multiple processors, while others, such as certain Siemens designs, realize redundancy in the internal software structure but still meet the same safety requirements.

Self-diagnostics run all the time in the background. Control.com highlights watchdog timers, memory checksums, and I/O health monitoring as standard practices. These routines verify that the logic is executing correctly, memory is intact, and communication paths are alive. The goal is to uncover latent faults before they combine into a dangerous failure. Electrical Engineering Resource points out that safety PLCs often provide detailed reliability data such as mean time to dangerous failure to support SIL and PL calculations.

Fail-safe behavior is non-negotiable. Safety outputs are designed and wired so that the safe state usually corresponds to de-energized outputs. If a processor fails, a communication link drops, or a critical diagnostic fails, the system defaults to that safe state. In motion systems, that may mean triggering Safe Torque Off on drives. In process control, it may mean closing valves and stopping pumps. Control.com and multiple application articles emphasize that safety PLC logic must always prefer the safe side in ambiguous conditions.

Certified safety function blocks simplify and harden the logic. Control.com and Automation Ready Panels both recommend using only vendor-certified safety blocks for core safety functions such as emergency stop, two-hand control, guard monitoring, muting, and safe speed. These blocks have been independently evaluated as part of the PLC platform’s certification, and they enforce design patterns that resist common implementation mistakes. Treat them as virtual safety relays that you assemble into higher-level functions, rather than writing your own low-level safety logic from scratch.

Diagnostics and HMI integration are another major benefit. Electrical Engineering Resource notes that modern safety PLCs expose real-time status of each safety device to an HMI, making it far faster to locate a tripped guard or a failed sensor than with hardwired relays. Ubest Automation reports that safety controllers with centralized diagnostics can cut troubleshooting time from hours to minutes, and in their experience this can reduce unplanned downtime roughly by an order of magnitude.

When you add hazardous areas into the mix, intrinsically safe PLCs extend this philosophy by adding energy-limiting and isolation circuitry, and by supporting certified intrinsically safe fieldbus and I/O modules. Intrinsically Safe Store also calls out the value of hot-swappable IS modules and built-in diagnostics, which let you replace faulty modules without shutting down an entire hazardous-area system and re-certifying the enclosure.

When SIL3 in a Hazardous Area Is Justified

Not every hazardous-area application needs a SIL3 safety PLC. Several sources stress that the correct starting point is a formal risk assessment. Mead & Hunt, Automation Ready Panels, and Venus Automation all describe the same basic steps: identify hazards, analyze severity and likelihood, consider foreseeable misuse and fault conditions, and then determine the required risk reduction and corresponding SIL or PL.

Venus Automation suggests that systems with complex machinery, high speeds, significant stored energy, or intense human interaction tend to drive requirements toward higher performance levels such as PL e and SIL3, especially when a fault could lead to serious injury or death. DO Supply and Ubest Automation both highlight robotics, stamping presses, large conveyors, and high-hazard process units as typical candidates where safety PLCs and higher SIL levels are warranted.

In hazardous-area sectors, the stakes are even higher. Intrinsically Safe Store cites estimates that the intrinsically safe equipment market is several billion dollars worldwide and growing at about 6–7% annually, driven largely by regulation and the high cost of ignition incidents. They also note that regulatory fines can reach about $100,000 per incident, and that average downtime can cost around $260,000 per hour in some industries. Against those numbers, the incremental cost of a SIL3-capable safety PLC that prevents a single major incident looks small.

On the other hand, Industrial Automation Co. and Electrical Engineering Resource both point out that for simple applications with only a few safety devices, safety relays can be more appropriate and cost-effective than a full safety PLC. A small pump skid with one emergency stop and a single guard switch in a Zone 2 location may not justify a SIL3 safety PLC, especially if a lower SIL or PL is sufficient based on the risk assessment.

A practical rule of thumb that emerges from these sources is that as the number of safety functions, zones, and operating modes grows, and as the risk of injury, explosion, or environmental damage increases, the balance shifts strongly in favor of a SIL-rated safety PLC architecture.

Designing a SIL3 Safety Architecture for Hazardous Areas

Once you know you need SIL3 in a hazardous area, the hardest work is still ahead. The architecture and engineering discipline will determine whether the system actually meets the target in real life, not just in a spreadsheet.

Start by treating safety as its own lifecycle, as Control.com recommends. That means documenting the required safety functions, the target SIL or PL for each function, and the assumptions behind those targets. Each safety function should be considered as a chain of inputs, logic, and outputs. Safety light curtains, emergency stops, guard switches, and gas detectors must themselves be safety-rated, with documentation for their contribution to overall risk reduction.

At the logic level, choose a PLC platform whose safety manuals explicitly support SIL3 for the types of architectures you intend to use. Venus Automation and Electrical Engineering Resource note that many widely used safety PLC families can achieve SIL3 and PL e when used with appropriate redundant architectures and diagnostics. Make sure that the safety PLC’s safety program is clearly separated, both logically and often physically, from standard control logic. Using the vendor’s safety function blocks and following their programming constraints is essential; bypassing those rules with custom code can undermine the certified integrity level.

For hazardous areas, use intrinsically safe PLCs and I/O where the controller or modules must be mounted directly in the zone. Intrinsically Safe Store recommends matching the PLC’s Ex rating to the zone: Ex ia for continuous-risk Zones 0 and 20, Ex ib for Zones 1 and 21, and Ex ic where allowed for Zones 2 and 22. Where the PLC remains in a safe area, use certified intrinsically safe barriers or galvanic isolators, and follow best practices for wiring segregation, grounding, and clear demarcation between hazardous and non-hazardous circuits.

Mochuan’s guidance on safety and compliance in PLC applications adds several foundational practices that apply equally here. Maintain strict access control to the PLC program, use secure communication and authentication for any remote connectivity, and keep firmware and software updated to address vulnerabilities and bugs. Combine these with scheduled proof testing of safety functions to show that safety devices still act as intended and that diagnostic coverage is holding up over time.

Finally, invest in people. Mead & Hunt, Mochuan, and Venus Automation all emphasize that operator and maintenance competence is a major safety factor. Training should cover how the safety system works, what alarms mean, and the correct steps for investigation and restart. Without training, even the best SIL3 design can be defeated by well-meaning but uninformed troubleshooting.

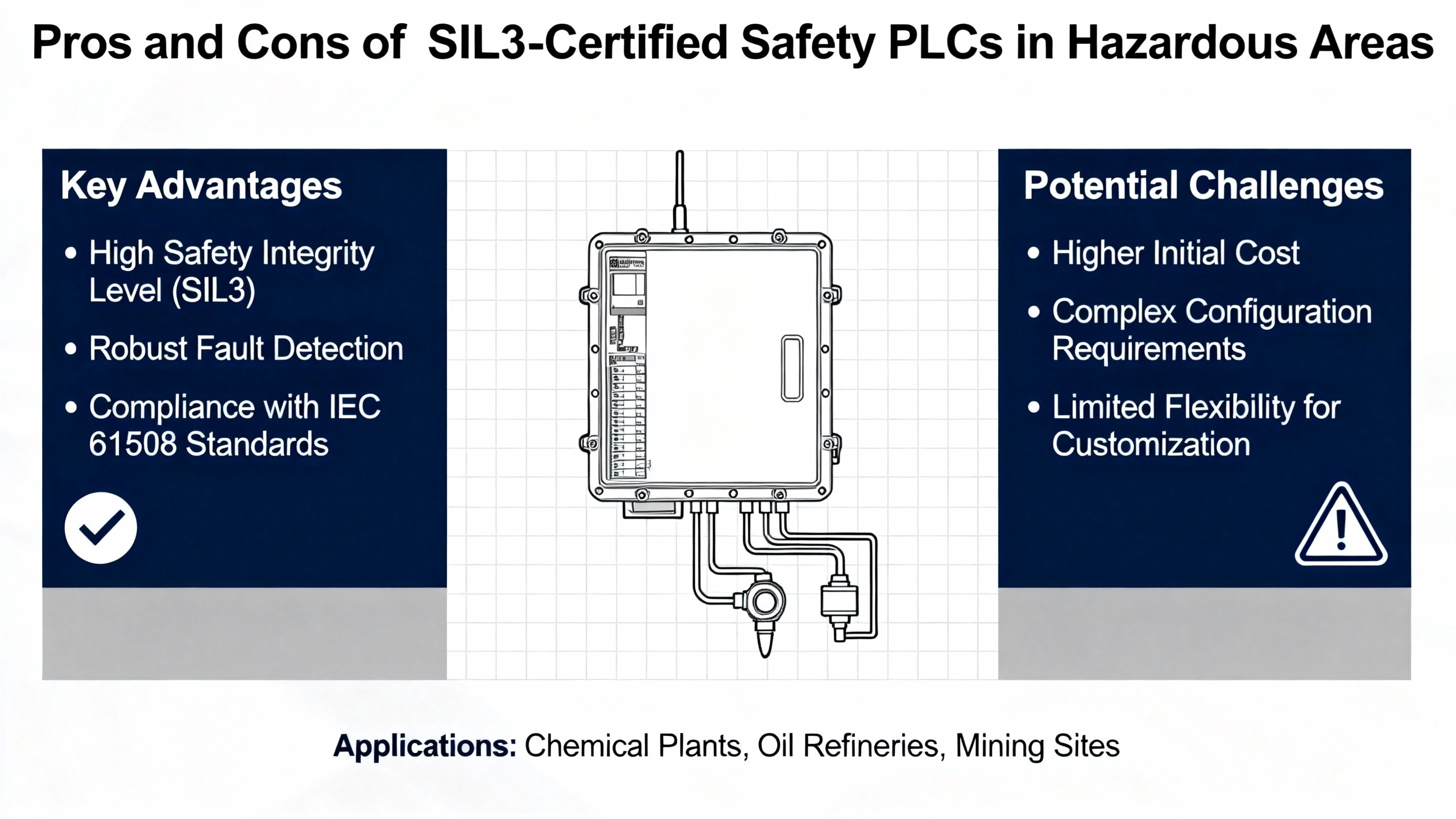

Pros and Cons of SIL3-Certified Safety PLCs in Hazardous Areas

The benefits of moving to a SIL3 safety PLC architecture in hazardous areas are substantial. Electrical Engineering Resource describes how one safety PLC can replace multiple hardwired safety relays and a separate standard PLC, shrinking panel space and cutting wiring. Industrial Automation Co. notes that software-based reconfiguration makes future modifications quicker and cheaper than rewiring relay logic, an advantage that grows as you standardize reusable safety code across similar machines or units. Diagnostics integrated into HMIs help technicians pinpoint the exact device or zone causing a trip, reducing restart time and avoiding unnecessary bypassing of safety devices.

From a risk perspective, DO Supply and Ubest Automation argue that safety PLCs significantly reduce the likelihood and severity of incidents by reacting faster and more predictably than general-purpose control logic. When you add hazardous-area considerations and intrinsically safe designs, you reduce ignition risk as well. Intrinsically Safe Store points to reductions in the likelihood of ignition-related incidents when intrinsically safe designs are used instead of traditional non-IS systems, and they highlight that improved maintenance and hot-swap capabilities further reduce downtime and human exposure in hazardous zones.

The drawbacks are real, though. Safety PLCs with SIL3 capability and hazardous-area certifications cost more up front than standard PLCs or simple relays. Engineering effort is higher as well; you must follow a structured safety lifecycle, perform proof calculations, and work within the constraints of the safety programming environment. Ubest Automation and Control.com both note that integration can be complex and that ongoing testing and revalidation are required throughout the plant’s life. Mochuan reminds us that redundancy, if applied carelessly, can introduce new failure modes such as synchronization issues or unexpected interactions between redundant paths.

In practice, these drawbacks are manageable with the right mindset. Instead of treating the safety PLC as a fancy standard controller, treat it as a safety instrumented system with a clearly documented scope, lifecycle, and owner. When that discipline is there, the long-term savings in downtime, incident avoidance, and smoother audits usually outweigh the initial investment, especially in hazardous-area facilities where the cost of one serious event can exceed the entire automation budget for years.

Practical Selection Considerations

The research from Maple Systems, Venus Automation, and Intrinsically Safe Store suggests a practical way to think about selecting a SIL3-capable safety PLC for hazardous areas.

Begin with compatibility and architecture. Ensure the candidate PLC integrates cleanly with your existing HMIs, drives, and networks, and that it supports the safety communication protocols you intend to use, such as PROFIsafe over PROFINET or CIP Safety over EtherNet/IP where those are part of the design. Decide early whether you want separate standard and safety PLCs or an integrated controller that handles both. In high-risk, complex applications, many engineers, including those cited by Electrical Engineering Resource and Ubest Automation, favor modern integrated safety controllers because they simplify wiring and centralize diagnostics.

Next, evaluate the hardware capabilities. Consider CPU performance, memory, and the quantity and type of safety I/O modules. Hazardous-area systems often have a mix of digital and analog safety signals, plus potentially intrinsically safe fieldbus segments. Ensure that the platform has certified IS I/O or can interface correctly with certified barriers and IS devices from the vendors specified in the intrinsic safety documents.

Environmental robustness and approvals come next. As Maple Systems and Intrinsically Safe Store both emphasize, you need the PLC’s temperature ratings, ingress protection, and vibration tolerance to match site conditions, and you must verify that the explosion-protection approvals match the zone or class. That means not just having an ATEX mark in general, but the right gas group, dust group, and temperature class to suit the actual installation.

Finally, look closely at support and lifecycle services. Safety PLCs demand good documentation, training, and responsive vendor assistance. Maple Systems highlights the value of strong manuals, example projects, and diagnostics tools. In hazardous-area SIL3 applications, you will also benefit from vendors and integrators who are comfortable assisting with SIL verification, safety function testing, and periodic revalidation.

Short FAQ

Q: If my PLC is SIL3-certified, is my whole system automatically SIL3?

No. All the sources that discuss functional safety, including Control.com and Venus Automation, emphasize that SIL is defined for a complete safety function, not for a controller in isolation. A SIL3-capable safety PLC is a building block. To achieve SIL3 for a given function you must also use appropriately rated sensors and final elements, design redundancy and diagnostics correctly, and follow the proof-test intervals and architectural constraints described in the safety manuals.

Q: Can I run my emergency stops through a standard PLC input in a hazardous area?

Several sources, including Ubest Automation, warn against this. While you can physically wire an emergency stop into a standard input, that input lacks the redundancy and self-testing required by functional safety standards. In hazardous areas, the stakes are even higher because a missed stop may also increase ignition risk. Safety standards expect safety-rated, redundant inputs and diagnostics, which you get with safety I/O on a safety PLC or with certified safety relays, not with a bare standard PLC card.

Q: Can I make a standard PLC intrinsically safe by adding barriers?

Intrinsically Safe Store is very clear that you should not attempt to retrofit a standard PLC to be intrinsically safe. Intrinsic safety requires purpose-designed hardware, certified energy-limiting circuits, and a documented system design. While you may, in some architectures, keep a standard or safety PLC in a safe area and use certified IS barriers and IS field devices in the hazardous area, the PLC itself is then outside the hazardous zone. Trying to claim that a standard PLC inside the hazardous area is intrinsically safe without proper certification is both non-compliant and unsafe.

Closing Thoughts

SIL3-certified safety PLCs and intrinsically safe architectures are not luxury features in hazardous areas; they are how you turn an inherently risky process into something you can run every day with confidence. When you couple a disciplined safety lifecycle with certified controllers, rigorously selected field devices, and trained people, you get a system that protects your team, your plant, and your balance sheet. As a project partner, my advice is simple: let productivity drive your control design, but let risk and standards drive your safety design, and do not compromise either when gas, dust, and high energy are in the same room.

References

- https://www.plowtech.net/what-is-so-special-about-a-safety-plc/

- https://www.plctalk.net/forums/threads/plcs-and-automation-safety.19516/

- https://www.mochuan-drives.com/a-news-safety-and-compliance-considerations-in-industrial-plc-controller-applications

- https://www.newark.com/a-comprehensive-guide-on-programmable-logic-controllers-trc-ar

- https://www.automationmag.com/770-integrating-safety-examining-the-benefits-of-a-safety-plc/

- https://venusautomation.com.au/how-to-choose-the-right-safety-plc/

- https://www.controleng.com/safety-plcs/

- https://electricalengineeringresource.com/4-benefits-of-safety-plcs/

- https://maplesystems.com/10-things-to-consider-when-choosing-new-plc/?srsltid=AfmBOoqYhDPL3VcNRhzYtrDEDRLINyrLOUJgx_lY61PxC9c33bHre3du

- https://meadhunt.com/industrial-automation-design/

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment