-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Urgent CNC Control System Parts: Critical Machining System Components

When a CNC machine stops in the middle of a high‑value job, it is almost never the casting or the bed that takes you down. It is almost always the control system: the brains, nerves, and muscles that turn G‑code into motion. After years on shop floors and inside retrofit cabinets, I have learned that the difference between a ten‑minute interruption and a ten‑hour outage often comes down to whether you have the right critical control components on the shelf and the discipline to deploy them methodically.

This article walks through the CNC control system from the perspective of urgent parts: what the key components are, how they fit together, where they fail, and how to prioritize spares. The goal is pragmatic: fewer surprises, faster recovery, and a more predictable machining operation.

Why CNC Control System Parts Matter So Much

CNC, or computer numerical control, is essentially subtractive manufacturing driven by digital instructions. As Clausing Industrial and Elemet Group both emphasize, computer‑controlled mills, lathes, routers, lasers, and waterjet machines rely on CAD/CAM‑generated instructions to drive multi‑axis motion with high accuracy and repeatability across automotive, aerospace, medical, electronics, and many other sectors. These machines can run continuously with minimal human intervention, and that is exactly why any control failure hurts so badly: the very automation that boosts productivity also concentrates risk.

Across the sources from Industrial Automation Co., PartzPro, and Xometry, you see the same architectural picture. Every CNC machine is built around a controller or machine control unit, a drive system with motors and ball screws, feedback devices, a human–machine interface, and the mechanical machine tool itself. The U.S. CNC market is projected in industry commentary from Industrial Automation Co. to be worth billions of dollars within this decade, driven by the need for safety, speed, and precision in industries from oil and gas to marine and electronics. In that context, a single line going down because of a dead servo drive or failed encoder is not a minor maintenance issue; it is a business risk.

From a systems integration standpoint, the control system parts are especially critical because they are tightly interdependent. The CNC kernel must communicate deterministically with drives and feedback devices over a fieldbus. The programmable logic controller must coordinate hydraulic clamps, tool changers, and safety interlocks. The operator relies on the control panel, display, and diagnostics to understand what is happening. When you choose what to treat as urgent spare parts, you are really choosing which parts of this chain you cannot afford to lose.

Inside the CNC Control System: From G‑Code to Motion

CNC Kernel and Machine Control Unit

According to the OPC Foundation’s description of CNC architecture and the component breakdowns from PartzPro, ACCURL, and Industrial Automation Co., the machine control unit is the core of the control system. The CNC kernel is the software and hardware that decodes the part program, performs path planning, and generates axis setpoints while respecting limits, kinematics, and machine constraints. The machine control unit reads G‑code or other NC languages, interpolates tool paths, and converts them into synchronized commands for each axis and spindle.

The machine control unit is also responsible for many auxiliary functions. The articles from Industrial Automation Co. and ACCURL both highlight that the controller starts and stops programs, controls spindle speed and direction, manages feed rate, and triggers tool changes and coolant. In practice, that means when the controller fails, you lose not only motion but also the orchestration of the entire machine. For urgent parts planning, the main CNC control hardware belongs at the top of your risk register, especially on machines that cannot be economically retrofitted quickly.

Traditional vendors like Fanuc, Siemens, Heidenhain, and Mitsubishi provide dedicated controller platforms that combine CNC kernel, HMI, and fieldbus interfaces in integrated hardware. Radonix and other PC‑based control vendors described in their own materials offer an alternative model where a standard PC and motion card host the CNC kernel. From a spare‑parts perspective, the first approach often ties you to specific OEM boards and modules, while the second may let you keep commercial PC components on the shelf and treat motion cards as the specialized spares.

PLC and Process Logic

The OPC Foundation notes that a programmable logic controller, usually compliant with IEC 61131‑3, runs alongside the CNC kernel. The PLC handles machine logic, interlocks, safety behavior, and coordination of auxiliary devices, using a tightly coupled CNC‑PLC interface to exchange data at high speed. In many machining centers, this PLC is physically part of the CNC controller; in others, it may be a separate unit.

When a PLC or its interface fails, you may see symptoms like the CNC program loading correctly but clamps not actuating, safety doors refusing to close, or tool changers stopping mid‑sequence. Logic faults can sometimes be corrected in software, but a failed PLC CPU or I/O module is a hard stop. That makes PLC hardware and critical I/O cards another category of control system parts that deserves urgent attention.

Drive System: Servo Drives, Motors, and Mechanics

Across cncmachines.com, PartzPro, and MRO Electric, the drive system is consistently described as the link between control instructions and physical motion. The drive system includes amplifier circuits, servo or stepper motors, and mechanical transmission such as ball screws or rack‑and‑pinion mechanisms. The CNC controller sends commands to drives, which regulate current and velocity in the motors to create precise axis movement.

Radonix explains the distinction between open‑loop and closed‑loop control in this context. Open‑loop systems, often using stepper motors without feedback, assume motion occurs as commanded and are common in light‑duty or hobby‑level machines. Closed‑loop systems use servo motors with encoders to measure actual position and continuously correct errors. Closed‑loop drives enable higher speeds, tighter tolerances, and more reliable operation under varying loads, at the cost of higher complexity and price.

Servomotor drives and amplifiers sit right in the middle of this feedback loop. When a drive fails, the axis cannot move at all or moves unpredictably, often triggering immediate faults. Because drives are highly model‑specific and often long‑lead components, they appear again and again in vendor literature, such as Industrial Automation Co. and MRO Electric, as critical CNC machine parts. For urgent repairs, having at least one compatible spare for each major drive family in your facility is a practical strategy.

Feedback System: Encoders and Scales

Sources like cncmachines.com, PartzPro, and Radonix all emphasize the importance of feedback systems. Position and speed transducers, usually rotary encoders or linear scales, measure the actual position of axes and spindles and feed this information back to the controller. In closed‑loop systems, drives and CNC kernel compare commanded and actual motion, correcting deviations in real time.

Radonix distinguishes between fully closed‑loop systems and semi‑closed‑loop systems. In semi‑closed designs, encoders are mounted on the motor shaft rather than directly on the moving axis. This ensures the motor does not lose position but leaves some vulnerability to mechanical backlash or belt stretch between the motor and the load. True closed‑loop systems add linear scales to measure table or carriage position directly.

Regardless of configuration, feedback devices are small, relatively fragile, and absolutely mission critical. A failed encoder can look like a drive fault or a mechanical jam, but the end result is the same: axis errors, following fault alarms, or wildly off‑tolerance parts. Given their modest cost relative to downtime, encoders, linear scales, and related feedback components deserve a place in your urgent parts strategy.

Human–Machine Interface: Control Panel and Display

Xometry’s overview of CNC machine parts and ACCURL’s guide to control units both call the control panel the “brain” from an operator’s perspective. The control panel houses the input device, keyboard, display unit, and function keys that allow the operator to load programs, change parameters, and monitor status. Industrial Automation Co. likewise highlights the display as a core component, showing programs, instructions, and live machine state.

Loss of an HMI or display may not stop the drives from functioning, but it effectively blinds the operator. Diagnostics, overrides, program selection, and setup all depend on a working interface. In many modern controls, the HMI hardware is tightly integrated with the CNC kernel, but some PC‑based systems use standard monitors and input devices. In planning urgent parts, consider which elements of the HMI are proprietary and which you can replace with off‑the‑shelf hardware.

Fieldbus, Drives, and I/O

The OPC Foundation describes the fieldbus interface as the communications backbone connecting CNC systems to drives, I/O modules, and other peripherals. It supports cyclic, time‑deterministic data exchange for motion control and asynchronous traffic for configuration, diagnostics, and higher‑level integration. Through this fieldbus and associated I/O, the CNC controller sees sensors, limit switches, and actuators across the machine.

In real installations, that means a failed fieldbus card, I/O module, or network interface can suddenly disconnect drives or entire sections of the machine. Because different vendors and generations use different fieldbuses, from dedicated motion buses to general industrial networks, you cannot assume interchangeability. For urgent parts, critical network and fieldbus cards should be treated with the same seriousness as drives and controllers, especially on machines that share common hardware across multiple assets.

Open‑Loop vs Closed‑Loop: Implications for Spare Parts

Radonix’s discussion of control loop types is directly relevant to spare parts strategy. Open‑loop systems send step commands to motors without any feedback; they are simple and cost‑effective for light loads and predictable applications like small routers or engravers. In these machines, the primary failure points in the motion chain are the stepper drivers and the motors themselves. Since there is no encoder, your urgent spare list can be shorter, although step loss and mechanical issues are still concerns.

Closed‑loop systems, built around servo drives and encoders, dominate industrial machining centers. Here, the chain is longer: the controller generates commands, the drive amplifies them, the motor moves, the encoder measures, and the feedback loop closes at high frequency. Failures can occur at any step, and each component has its own model dependencies. In semi‑closed‑loop systems, encoder placement on the motor shaft simplifies mechanical mounting but still leaves the encoder and drive as critical components. In fully closed‑loop systems with linear scales, you add yet another device that must remain accurate and functional.

The key implication is straightforward. The more sophisticated your control loop, the more feedback‑related hardware you must treat as urgent. For high‑precision machines in aerospace, medical, or mold work where tight tolerances are non‑negotiable, you should plan to hold spares for not just drives and motors but also encoders, scales, and key cabling components.

Comparing Critical Control Components by Urgency

The various industry guides converge on a set of components that are both central to CNC function and vulnerable to causing extended downtime when they fail. The table below summarizes the most important control system parts through the lens of urgent spares.

| Component category | Primary role in the system | Typical failure impact | Spare urgency for production shops |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNC controller / MCU | Interpret programs, generate motion, coordinate auxiliaries | Machine fully inoperable; no programs or motion allowed | Highest; a compatible replacement is essential |

| Servo drive / amplifier | Convert control commands to motor current and velocity | Axis or spindle drops out, frequent faults, no motion | Very high; long lead times and model specificity common |

| Axis and spindle motors | Provide mechanical power to axes and spindle | Loss of axis or spindle motion, overheating, tripping | High; especially for unique frame sizes or special motors |

| Feedback devices (encoders, scales) | Measure position and speed for closed‑loop control | Following errors, loss of homing, poor accuracy | High; relatively low cost compared with downtime |

| Fieldbus and I/O modules | Connect controller to drives, sensors, and actuators | Loss of communications, whole subsystems offline | Medium to high; depends on network commonality |

| HMI panel and display | Provide operator interface and diagnostics | Limited control, no clear fault information | Medium; critical for complex setups and troubleshooting |

These categories are all described in different ways across PartzPro, MRO Electric, cncmachines.com, Xometry, and the OPC Foundation, but the underlying message is consistent. If your business depends on a machine, treat its controller, drives, motors, feedback devices, and communications hardware as critical, not optional, spares.

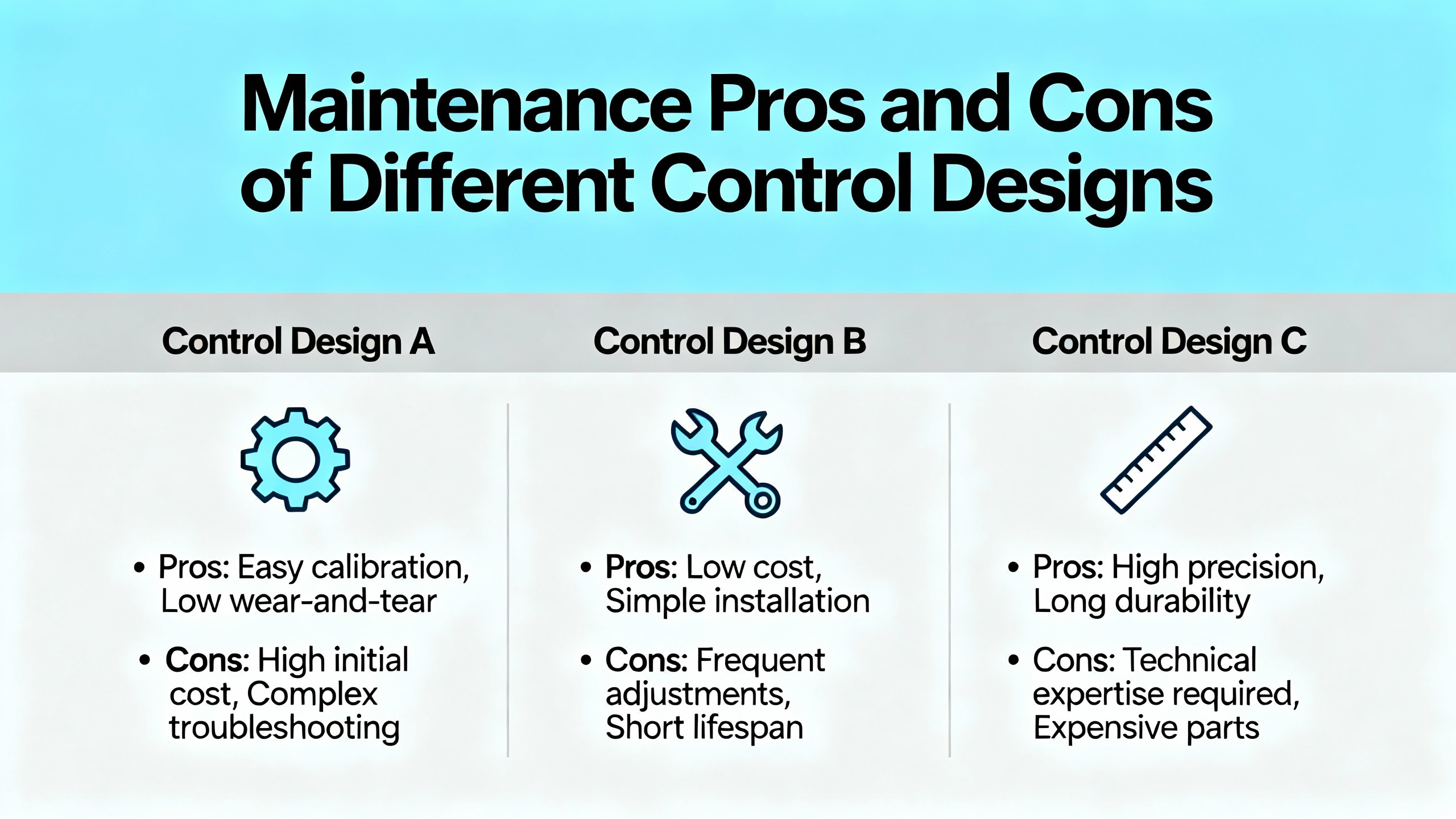

Maintenance Pros and Cons of Different Control Designs

Your choice of control architecture influences not only how the machine performs but also how you manage urgent parts.

Dedicated CNC controllers from vendors such as Fanuc, Siemens, Heidenhain, and Mitsubishi focus on stability, high precision, and strong self‑diagnostics, as noted in MyLas CNC’s overview of controller brands. The advantages for maintenance are predictable behavior, robust error reporting, and long‑term support for specific hardware families. The tradeoff is that many parts are proprietary, so you often need vendor‑specific boards, drives, and I/O modules on the shelf or a fast relationship with a supplier who stocks them.

PC‑based controllers, such as those described by Radonix, leverage standard PCs plus motion cards and software. Benefits include open architecture, easier Industry 4.0 connectivity, and flexibility to upgrade processors or storage independently. For urgent parts, this can simplify stocking because commodity PC components are widely available, and you can focus your spare budget on the specialized motion and I/O cards. However, you must manage the complexity of operating systems, software updates, and potential compatibility issues between newer PC hardware and legacy motion cards.

On the control loop side, open‑loop systems have fewer electronic parts to stock, but they impose limits on speed and torque to avoid missed steps. Closed‑loop systems require more feedback devices and more sophisticated drives but deliver higher accuracy, better error detection, and greater reliability under variable loads. In mission‑critical industries such as aerospace and medical, as highlighted by American Micro Industries and Sytech Precision, those benefits justify the additional parts inventory.

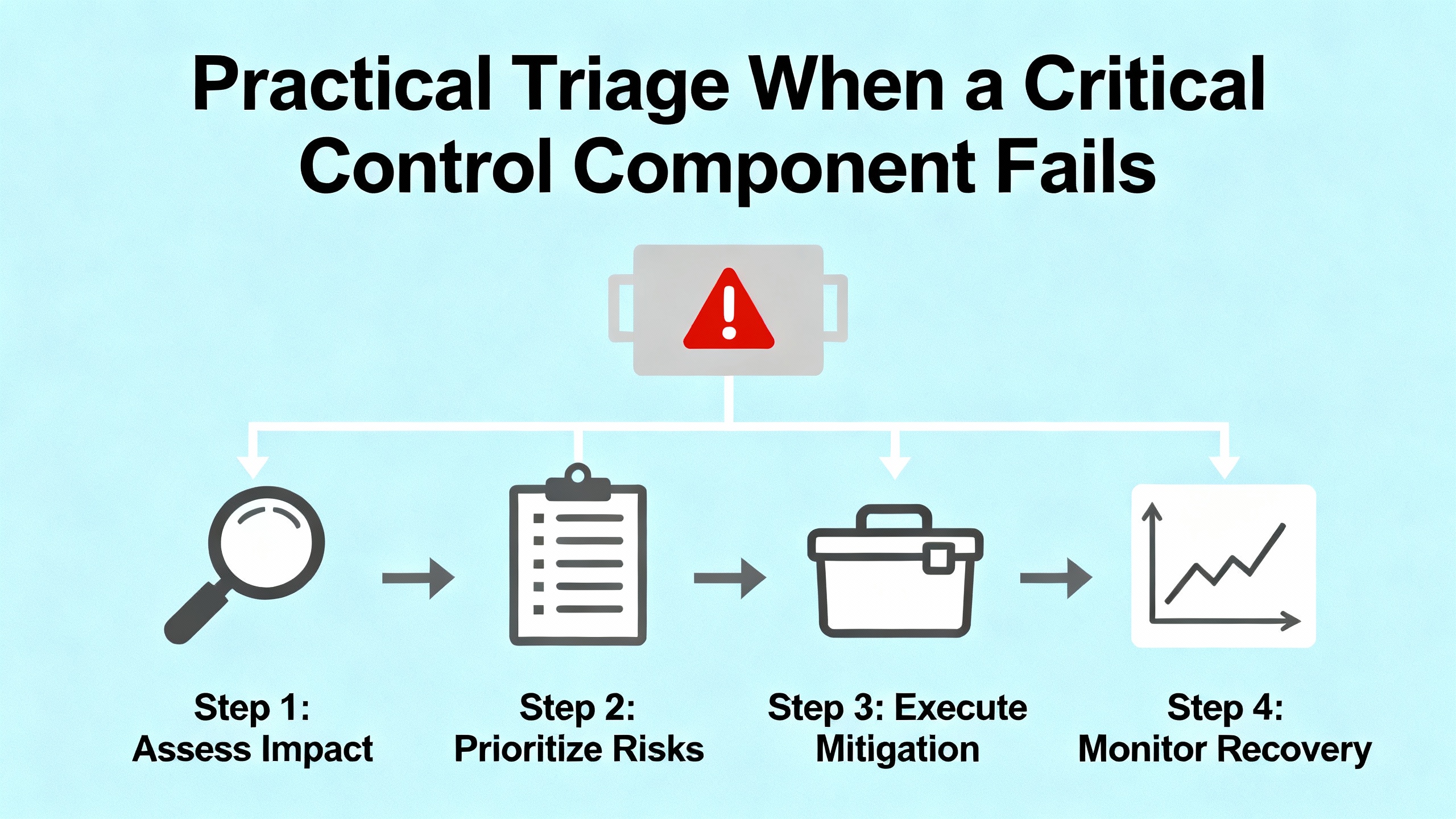

Practical Triage When a Critical Control Component Fails

When a CNC machine stops unexpectedly, the worst thing you can do is start randomly swapping parts. Standard Bots, in its guidance on CNC controls, recommends a disciplined troubleshooting process: read error codes, check manuals, inspect hardware, and only then move on to component replacement. From a systems integrator’s perspective, that approach is not optional; it is essential for avoiding new problems.

Start with the controller diagnostics and error messages. Modern CNC controls, whether G‑code‑centric or conversational as described by Standard Bots, provide detailed alarms for axis faults, communication errors, and configuration issues. Cross‑reference these with the manufacturer’s documentation before touching hardware. Many failures that look like bad drives or encoders turn out to be configuration changes, parameter corruption, or even misunderstandings of homing logic.

Next, inspect physical connections and basic conditions. Standard Bots notes that loose cables, dust buildup, and worn connectors can all mimic deeper failures. Check fieldbus and feedback connectors, power supplies, and grounding. Look for obvious damage such as scorched components, bent pins, or cracked insulation. In many cases, simply reseating connectors or replacing a damaged cable resolves intermittent faults.

If the fault persists, use isolation to narrow down the culprit. Swap a suspect drive with a known‑good one on a noncritical axis if the hardware and configuration allow it. Move an encoder cable to a spare channel where possible. This needs to be done carefully and methodically, but it can quickly identify whether the issue follows the component or stays with the axis.

Only after you have narrowed the failure to a specific module should you deploy one of your urgent spare parts. When you do, keep the failed unit for later analysis rather than discarding it. If you see repeat failures on the same type of module, that is often a sign of underlying issues such as power quality, environmental conditions, or misconfiguration rather than component weakness alone.

Building a Pragmatic Urgent Parts Strategy

A practical urgent‑parts plan for CNC control systems does not start with catalogs; it starts with your installed base and your production risk. The industrial articles from PartzPro, MRO Electric, Xometry, and Industrial Automation Co. all stress that understanding the architecture of your machines is foundational. Map out, for each major asset, the make and model of controller, drives, motors, feedback devices, fieldbus interfaces, and I/O modules. Note which hardware is common across multiple machines and which is unique.

Focus first on parts that combine high impact, higher failure likelihood, and longer lead times. Controllers and servo drives are usually at the top of this list. Motors and encoders come next, especially for axes that do the hardest work. Fieldbus cards and essential I/O modules deserve attention on machines where a single failure disables entire subsystems. For HMI panels and displays, urgency depends on how tightly they are integrated; a commodity monitor attached to a PC‑based control can often be replaced quickly, while a proprietary integrated panel is another story.

Consider the nature of your work as well. Shops doing tight‑tolerance aerospace or medical components, as discussed by American Micro Industries, Elemet Group, and Sytech Precision, rely heavily on closed‑loop control and high‑performance drives. For them, precision feedback devices and high‑end drives are not just components; they are enablers of their business model. High‑mix job shops with frequent changeovers may rely more on their HMIs and conversational controls, making user interface hardware more critical.

Finally, align your spare parts strategy with your control technology roadmap. If you plan to retrofit older machines with modern controls, as suggested in the Standard Bots and Radonix materials, think carefully before buying deep inventories of obsolete controller boards. Sometimes it is better to hold just enough to keep a machine running until a planned upgrade, rather than tying up capital in parts for a platform you intend to replace.

Short FAQ: Real‑World Questions from the Shop Floor

Q: If I can only afford a limited set of urgent control spares, what should I prioritize?

A: Prioritize at least one compatible controller or main CPU module for each major control platform you run, plus servo drives for the most critical axes, a selection of encoders that cover your primary motor sizes, and any unique fieldbus or I/O cards whose failure would stop multiple machines. These categories line up with the core components called out by PartzPro, MRO Electric, and the OPC Foundation and tend to have the longest lead times and the most specific compatibility requirements.

Q: How can I tell whether a motion problem is caused by the drive, the motor, or the encoder?

A: Use the controller’s diagnostics first. Axis following errors that appear at high speeds may suggest feedback issues, while drives that fault as soon as they are enabled can point toward drive or motor problems. Swapping suspected components with known‑good hardware on a less critical axis, when safe and possible, can help you isolate the fault. The open‑loop versus closed‑loop distinctions described by Radonix remind us that in closed‑loop systems the drive, motor, and encoder form a single control loop; failures anywhere in that loop can produce similar symptoms, which is why methodical isolation is so important.

Q: Do advanced features like AI‑enabled controls and CNC‑tending robots change my urgent parts strategy?

A: They change the perimeter but not the core. As Automation Within Reach and Standard Bots discuss, automation around CNC machines—robots for loading and unloading, vision systems for inspection, analytics dashboards for monitoring—adds more devices that must talk reliably to the CNC controller. This means additional network interfaces, safety I/O, and sometimes specialized controller modules to support robotics. You still need to protect controllers, drives, motors, and feedback devices first, but once those are covered, you should also consider spares for the added automation components that can stop the cell even if the CNC itself is healthy.

In my experience, the shops that stay productive under pressure are the ones that treat their CNC control system like the mission‑critical infrastructure it is. They understand each component’s role, stock spares where it counts, and follow disciplined troubleshooting practices rather than guesswork. If you build that mindset into your maintenance and capital planning, you will not eliminate every failure, but you will turn most of them from emergencies into manageable interruptions—and that is what a reliable project partner should be aiming for.

References

- https://reference.opcfoundation.org/CNC/v100/docs/4.1.1

- https://www.modelcraft.net/8-reasons-why-cnc-precision-machining-is-so-important

- https://cncmachines.com/parts-of-a-cnc-machine-cnc-block-diagram?srsltid=AfmBOorlGKTN0VHedftj0NlsDCM4HuFyiP9cAPbllcurlLbRy8TNQIOK

- https://www.mylascnc.com/the-importance-and-advancements-of-cnc-controllers

- https://www.automationwithinreach.com/blog/exploring-and-understanding-cnc-automation

- https://clausing-industrial.com/cnc-machines-and-their-role-in-modern-manufacturing/

- https://elemetgroup.com/cnc-machines-what-they-are-and-how-they-work/

- https://www.kesmt.com/understanding-cnc-machines-how-they-work-and-what-you-need-to-know/

- https://machiningconceptserie.com/essential-cnc-components-you-need-to-know-about/

- https://wiki.mcneel.com/rhino/cncbasics

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment