-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

How to Verify Genuine Allen-Bradley Parts from Authorized Sources

As someone who has spent years commissioning Allen-Bradley systems in plants that cannot afford to stop, I have learned that nothing kills a project faster than “cheap” hardware that turns out not to be what it claims. Counterfeit and gray‑market Allen‑Bradley parts do not just annoy purchasing; they create real safety, reliability, and cybersecurity risks that show up months or years later, often when the line is at peak load.

Verifying that your Allen‑Bradley hardware is genuine starts long before you open a box and look at the label. It is a supply‑chain decision, a procurement discipline, and, in high‑risk cases, a matter of technical inspection. This article walks through a practical, field‑tested approach to staying on the right side of Rockwell Automation’s authorized channels and avoiding the traps that forums, refurbishers, and marketplace veterans have been warning about for years.

Why Counterfeit Allen‑Bradley Parts Are a Real Risk

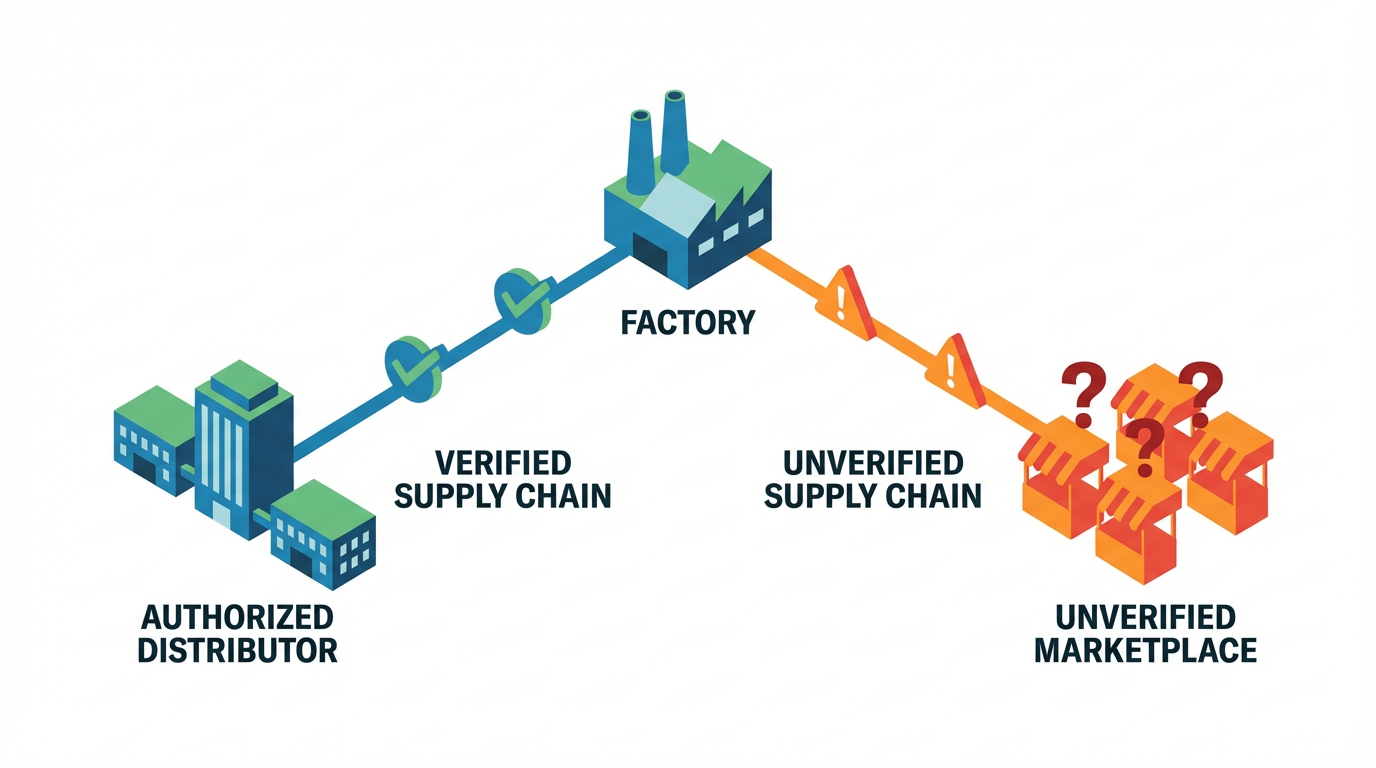

Rockwell Automation has been explicit in its guidance on unauthorized sources and counterfeit products. The company runs a limited distribution model: products are sold either directly or through an authorized distributor network, and those distributors are contractually prohibited from feeding unauthorized resellers. Anything outside that ecosystem is, by Rockwell’s own description, gray market at best.

In Rockwell’s case studies, customers who tried to save money by buying “new” Rockwell‑branded products from unauthorized resellers discovered that boxes, seals, and labels had been faked. In one North American example, a customer ordered items from a reseller that claimed to be US‑based, only to have the shipment actually originate in China. Rockwell experts then confirmed that a significant share of the parts in that shipment were counterfeit. In other regions, engineering teams noticed quality drops and commissioning faults; investigation revealed counterfeit devices and forged paperwork used to present unauthorized suppliers as legitimate.

The consequences went well beyond the cost of a few modules. Organizations had to revalidate installations, rip out suspect hardware, and manage the embarrassment and reputational damage of having counterfeit equipment installed in critical infrastructure. Rockwell’s conclusion from those cases is blunt: once you factor in rework, downtime, and risk, customers generally end up worse off than if they had bought directly from Rockwell or an authorized distributor.

Academic and reliability research reinforces why this matters. Work summarized by the University of Florida hardware security group highlights that counterfeit electronics are both widespread and difficult to detect reliably. They describe multiple counterfeit types in the supply chain, from recycled and remarked parts to cloned and tampered devices, and show that identifying them often requires specialized physical inspection or electrical testing rather than a quick visual check.

A study on counterfeit electrolytic capacitors in medical equipment, indexed by ADS, examined field failures where fake capacitors had been installed in power supplies. The investigators used methods like optical inspection, X‑ray, electrical parameter measurements over temperature, and chemical analysis of the electrolyte. They found broader parameter distributions and out‑of‑spec behavior in counterfeit parts, particularly at temperature extremes. The lesson for industrial automation is straightforward: counterfeits often fail earlier and less predictably than genuine components, and you usually discover the problem only after a fault in service.

When you combine Rockwell’s case studies with this broader body of evidence, the message is clear. Verifying authenticity is not a nice‑to‑have. It is part of protecting production, safety, and OT security.

Authorized Channels versus Gray Market Sources

From a systems integrator’s point of view, the single most important authenticity check is where the product came from. Rockwell’s own blog on unauthorized sources defines the gray market as trade in Rockwell Automation products advertised as new outside authorized channels. These products can be surplus, old, used, modified, or fully counterfeit. The blog describes common behavior from unauthorized resellers: repackaging used devices in new boxes, applying fake factory seals and fake labels, and representing all of it as new.

To make the distinction concrete, it helps to lay out how different source types compare.

| Source type | Typical characteristics | Primary authenticity lever |

|---|---|---|

| Rockwell Automation direct | Controlled pricing and terms, clear product history, factory documentation and support | Contractual chain from factory to you |

| Authorized Rockwell distributor | Formal relationship with Rockwell, trained sales and support, traceable order and invoice history | Distributor’s agreement with Rockwell and official warranty |

| Specialist refurbisher with Rockwell focus | Opens units, replaces known‑failure components, fully tests, offers explicit warranty and test reports | Depth of refurbishment process and willingness to stand behind repairs |

| General surplus dealer (non‑authorized) | Mixed inventory, varying documentation quality, opportunistic sourcing | Supplier reputation and willingness to prove source and test results |

| Marketplace seller on auction sites | Wide range of claims, from honest surplus to deliberate counterfeits; frequent use of marketing phrases rather than traceability | Your due diligence and the platform’s buyer protection policies |

In my own projects, anything not purchased through Rockwell or an authorized distributor is treated as higher risk by default.

That does not mean you can never use surplus or refurbished hardware, but you should treat it as conditional on evidence: test reports, warranty terms, and a track record of supporting what the seller claims.

Rockwell’s terms and conditions of sale make another important point. Genuine new hardware from Rockwell carries a one‑year warranty for defects in material, workmanship, and design. Factory remanufactured or field‑exchange hardware carries its own warranty period, and “open box” hardware has a shorter warranty window. Those warranties are tightly tied to purchases made under Rockwell’s terms. If hardware has bounced through unauthorized resellers, you may find it difficult in practice to claim those benefits, even if the part itself started life as genuine.

What “Counterfeit” Means In the Allen‑Bradley World

When engineers hear “counterfeit,” many imagine a completely fake module with bad firmware and a wrong logo. Rockwell’s own wording, as cited in practitioner guides such as NJT Automation’s work on fake Allen‑Bradley parts, defines it more broadly. Any Rockwell Automation trademarked product that contains non‑factory‑original elements but is advertised as new falls into the counterfeit bucket.

That definition sweeps in several categories. Used modules that have been cleaned, placed in a new box, and sold as “brand new” are counterfeits if they carry Rockwell’s trademarks and are presented as new. Hybrid units that combine genuine circuit boards with aftermarket plastics, overlays, or keypads are also counterfeit, even if they function similarly to the originals. At the far end are fully cloned units with completely non‑Rockwell electronics and packaging.

NJT Automation notes that hybrid fakes are currently more common than perfect clones. They often behave acceptably in short tests because the core electronics may be genuine, but the non‑original mechanical parts, overlays, or reworked components introduce risks the original product was never qualified for. Spotting those hybrids without opening the device can be challenging.

The academic taxonomy from the University of Florida group adds more nuance. They describe counterfeit types such as recycled, remarked, overproduced, out‑of‑spec or defective, cloned, forged documentation, and tampered. Every one of those types has an industrial hardware analog. Remanufactured drives without disclosure look a lot like recycled parts sold as new. Labels that hide the original catalog number resemble remarked components. Gray‑market parts that come from overproduction or fraudulent documentation fall into the same conceptual categories.

For a plant or integrator, that means authenticity is not a binary question of “real versus fake.” It is about whether the part in your hand matches what Rockwell designed, manufactured, and supports, and whether its history is transparent enough that you are comfortable putting it on a safety circuit or critical production line.

Using Secondary Markets Without Getting Burned

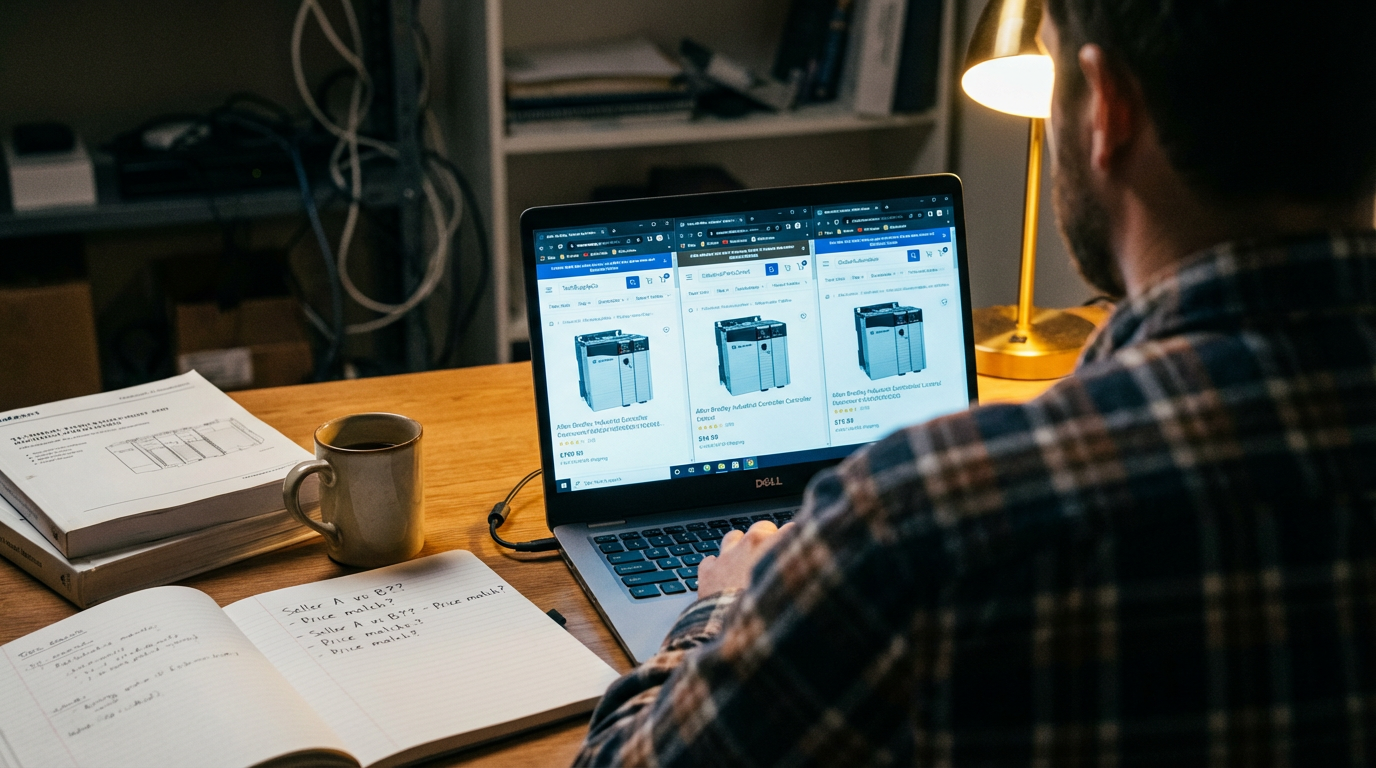

There are times when you simply cannot find a discontinued Allen‑Bradley catalog number through official channels. That is when managers open their browsers, type the part number into an auction site, and get flooded with “New” results at wildly different prices.

Long‑time marketplace sellers and independent automation firms have provided detailed advice on how to navigate those waters. An experienced e‑commerce seller operating as THEPLCDEPOT, with nearly two decades on a major auction platform, has documented patterns they see in genuine versus fake Allen‑Bradley offerings. NJT Automation has provided a complementary guide focused on identifying fake Allen‑Bradley parts on online marketplaces. Taken together, they outline a pragmatic screening process.

Before You Buy: Reading Sellers and Listings

The first filter is seller history. Experienced surplus sellers who specialize in Allen‑Bradley hardware typically have years of account history and a consistent stream of similar inventory. Their feedback over the last year tends to show repeat buyers and detailed comments from engineers and maintenance teams who actually installed the gear. In contrast, many counterfeiters operate through new or frequently replaced accounts. If you see a brand‑new account suddenly offering a large volume of “new” Allen‑Bradley modules at prices far below the market, caution is warranted.

Language and presentation matter as well. THEPLCDEPOT notes that low‑effort, generic greetings such as “Dear friend” and formulaic descriptions can signal large overseas operations that sell whatever they can source cheaply, rather than specialized industrial suppliers. That by itself is not proof of wrongdoing, but it belongs on your mental checklist.

Next, look at how the seller presents photos. Reputable surplus sellers generally photograph the actual item for sale. You will see multiple angles, branding watermarks, and a consistent photography style. Serial numbers might be partially obscured to prevent serial hijacking, but the rest of the label is visible. By contrast, counterfeit‑prone listings often rely on generic catalog photos or a single low‑resolution image that could have been copied from anywhere. If the same photo appears across multiple accounts or part numbers, that is another hint that you are not seeing the real item.

Shipping details can reveal as much as the photo. One pattern highlighted by NJT Automation is the overseas seller that claims to be stocking items in the United States. Listings shout “US STOCK” or “Fast Free Shipping” and may display American flags or delivery service logos, but delivery estimates quietly stretch into multi‑week windows. Some of these listings cluster around suspiciously narrow price bands for “brand new” modules, for example in the mid‑ninety‑dollar range, regardless of what genuine parts actually cost through authorized channels. That kind of artificial price clustering is exactly what you see when multiple resellers are feeding off the same counterfeit source.

The shipping method and handling time tell you more. An honest US‑based surplus house will usually offer standard carriers such as USPS, FedEx, or UPS with realistic one to three business day handling times. Listings that show vague or obscure carriers and long delays before shipment often indicate that the seller is simply brokering goods from overseas warehouses, even when the location is claimed to be domestic.

Pricing itself is a powerful sanity check. Industrial buyers will routinely pay fifty to two hundred percent more for a part that is truly new compared to clearly used surplus. That price gap creates the incentive to mislabel used, cleaned, or poorly refurbished parts as “New” or “New Old Stock.” When you see a “new” listing that is only slightly more expensive than obvious used units, or dramatically cheaper than pricing from established surplus houses, assume you are looking at something other than a factory‑fresh part.

Finally, consider how much the seller is willing to reveal about buyers and returns. Private listings, where buyer identities are hidden, are unusual in the industrial world. THEPLCDEPOT points out that legitimate sellers have no reason to hide who is buying from them. Meanwhile, a vague or restrictive return policy is a red flag. Strong sellers typically offer clear, straightforward returns and often pay return shipping when they are at fault, because they expect the parts they ship to work.

After You Receive the Part: Inspect, Test, Decide Quickly

Even with rigorous pre‑purchase screening, you should treat any “new” Allen‑Bradley hardware from secondary markets as untrusted until you have put it through basic checks. NJT Automation stresses that the clock starts ticking as soon as the package arrives, because buyer protection programs such as a platform’s money‑back guarantee usually have strict time limits.

Start with the box and label. Look for home‑made labels, mismatched fonts, and stickers that do not line up with the printing underneath. Genuine Rockwell packaging tends to be consistent. Labels that are obviously peeling, misaligned, or hiding another label underneath are cause for concern. Missing, blurred, scratched, or completely sticker‑covered serial number plates are even more serious. Those can indicate stolen or contract‑restricted items, serial numbers reused across multiple fakes, or other gray‑market sourcing. At this point, your goal is not to play detective; it is to decide whether you are comfortable installing the part or whether it should go back to the seller.

Examine the hardware for evidence of prior installation. Mounting feet with marks, worn screw heads, discolored plastics, and pre‑installed aftermarket overlays or keypads all indicate that the unit has lived a previous life. Some of that may be acceptable if the part was sold explicitly as refurbished and tested. It is not acceptable when you paid for new.

Many Allen‑Bradley HMIs and variable‑frequency drives provide access to runtime hours and other service diagnostics through hidden or engineering menus. NJT Automation recommends using those diagnostics to check whether the run hours make sense for a supposedly new or barely used unit. A panel that reports years of runtime when it was sold as “unused surplus” should be considered misrepresented at best.

Power‑on tests are another practical line of defense. On HMIs, look for dim or uneven backlighting, ghosting, or color shifts that suggest an aging display. On drives and controllers, check that key diagnostics and communication indicators behave exactly as specified in Rockwell documentation. When something feels off, capture photos and screenshots immediately and use the platform’s dispute mechanism while your return window is still open.

Over time, an experienced maintenance or engineering team will develop its own intuition about what genuine Allen‑Bradley hardware looks and feels like out of the box. Until then, the safest mindset is the one NJT Automation advocates: treat every “New” marketplace listing as guilty until proven innocent.

Labels, QR Codes, and the Limits of Online Verification

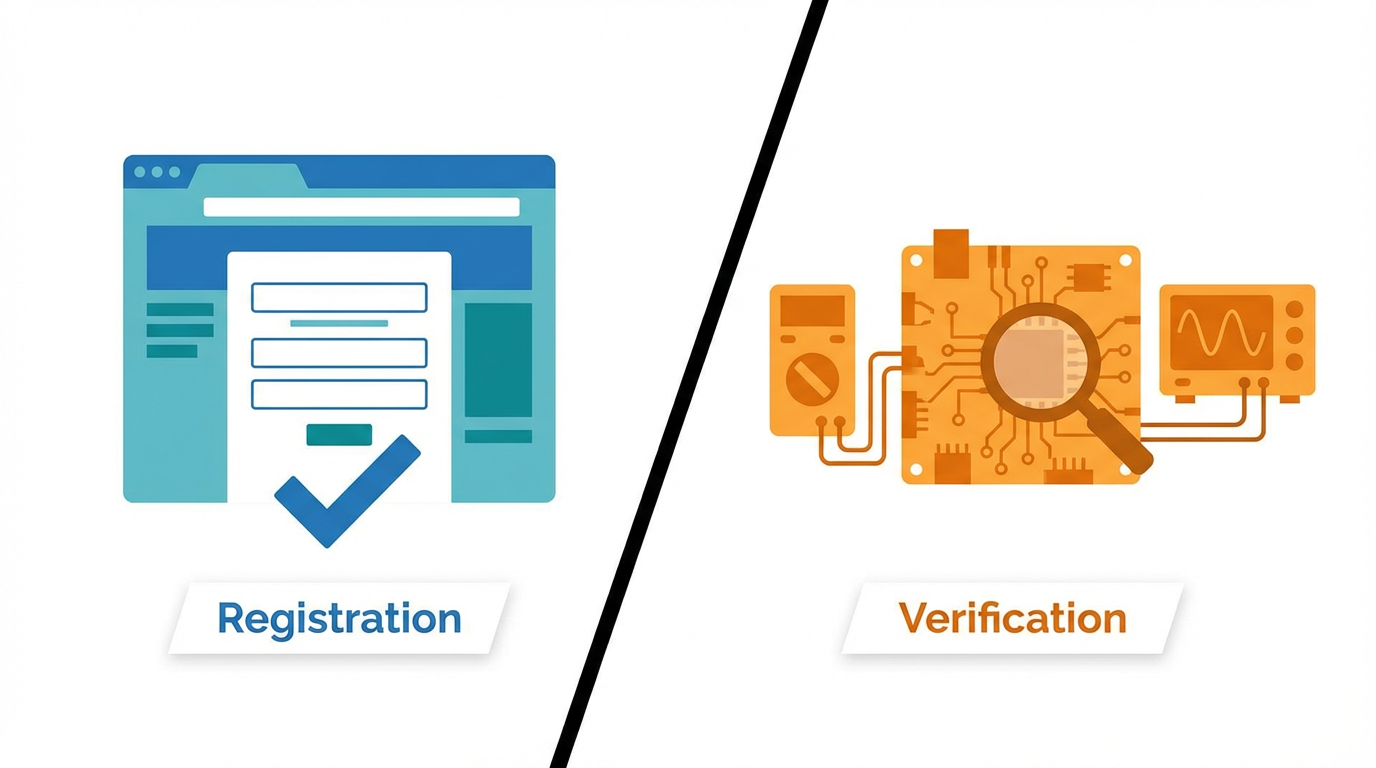

A recurring question on specialist forums such as MrPLC is whether it is possible to authenticate an Allen‑Bradley product purely by scanning the codes on the box or entering information into a Rockwell website. One thread describes a box label covered with barcodes, a QR code, and various numeric and alphanumeric identifiers. The poster asks whether Rockwell offers an online service where that data can be submitted to confirm authenticity.

Other practitioners point to Rockwell’s product registration workflows, which rely on catalog and serial numbers printed on the label. However, as one author notes, those registration pages are primarily about establishing ownership for warranty and asset tracking rather than acting as a formal authenticity checker. The distinction is important. Ownership registration and authenticity verification are related but different problems. Registration ties a serial number to a customer in Rockwell’s systems. Authenticity verification would need to prove that the unit itself, and not just the serial number, is genuine.

Rockwell does publish material on security and anti‑counterfeit labels and offers support content under titles such as “Verify whether a Rockwell Automation product is authentic or a suspected counterfeit product.” In the available excerpts, that material is positioned within a broader operational technology security context, including case studies where enhancing OT security reduced labor costs and improved visibility across operations. The essential implication for end users is that Rockwell treats authenticity as part of supply‑chain and OT security, not as a stand‑alone website where a QR scan magically answers every question.

Given these realities, you should treat label and QR information as tools for traceability rather than definitive authenticity tests. Use the catalog and serial numbers to check that documentation and firmware versions match what you received. Keep copies of invoices and purchase confirmations that show which entity sold you the device. When something looks suspicious, engage Rockwell or your authorized distributor with that evidence. They are in the best position to investigate whether a particular serial number has a problematic history, especially when combined with photos of the hardware and packaging.

What you should not assume is that simply registering the product online proves that the physical device in your hand is genuine.

Forum discussions make clear that this is a common misconception.

Technical Inspection versus Supply‑Chain Assurance

In very high‑risk environments, some teams consider deeper technical inspection of suspect hardware. Research on counterfeit detection for integrated circuits, such as work summarized by the University of Florida group, shows that physical inspection and electrical testing can be extremely powerful but also costly and specialized. Physical inspection techniques range from simple visual checks to X‑ray, infrared imaging, and even electron microscopy. Electrical tests measure parameters across conditions and compare them to known‑good distributions.

The study of counterfeit electrolytic capacitors in medical devices described earlier combines both approaches into an offline reliability assessment methodology. The authors used optical and X‑ray inspection, weight measurement, electrical parameter testing over temperature, and chemical analysis of the electrolyte using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. They found that counterfeit capacitors not only had different chemical composition but also electrical characteristics that fell outside specification at the lowest and highest rated temperatures.

For most industrial plants, it is not practical to run this kind of laboratory‑grade analysis on suspect Allen‑Bradley modules. The equipment and expertise required are substantial, and some tests are destructive. That is precisely why both Rockwell and the academic community emphasize prevention and supply‑chain integrity. Rockwell’s own blog stresses avoiding gray‑market and unauthorized resellers altogether. Hardware security researchers highlight design‑for‑anti‑counterfeit techniques and traceability measures such as tagging and provenance tracking.

From a practical standpoint, that means your first line of defense should be procurement policy and supplier choice. Technical inspection is a last resort for extremely critical installations or forensics after a problem has already occurred.

Choosing Between Genuine New, Refurbished, and “Too Good to Be True”

One nuance worth emphasizing is that professionally refurbished drives, HMIs, and controllers are not inherently a bad choice. NJT Automation argues, and field experience supports, that high‑quality refurbishers often produce more reliable results than decade‑old new‑old‑stock that has sat on a shelf. Good refurbishers open units, clean them, replace known‑failure components such as capacitors, backlights, and gaskets, and then fully test the unit under load. They typically provide a defined warranty period, often on the order of a year, at a lower price than many dubious “new” listings.

Rockwell itself offers factory remanufactured and repair services with formal warranties defined in its terms and conditions. Non‑warranty remanufactured or field‑exchange hardware and repaired components are warranted for a year from shipment, with defined coverage for any replacements under that warranty. While those services are not the same as third‑party refurbishment, they set a benchmark for what “remanufactured” should mean in terms of process and support.

Meanwhile, the common gray‑market pattern is exactly the opposite. Sellers take used or partially repaired hardware, do the minimum cosmetic cleanup, put it in a box with a fresh label, and sell it as new. There is no transparency about what was replaced, no meaningful test documentation, and only the weakest form of warranty, if any. Once problems appear, the seller disappears or blames installation.

For engineering and maintenance teams, the practical approach is to define different risk tolerances for different applications. On safety‑related or highly critical production loops, insist on genuine new products from Rockwell or authorized distributors. On non‑critical or legacy subsystems where the platform itself is end‑of‑life, a mix of Rockwell remanufactured units and carefully vetted third‑party refurbishment may be reasonable, especially when you have seen those refurbishers stand behind their work. What is rarely justified is trusting anonymous marketplace sellers who cannot explain where their “new” inventory came from.

Building a Procurement Discipline That Keeps You Out of Trouble

Over time, plants that consistently avoid counterfeit Allen‑Bradley hardware tend to share the same habits. They treat Rockwell’s restricted distribution model as a design constraint, not an inconvenience. They establish a short, approved list of sources for Rockwell products and make it clear that purchasing off that list requires engineering approval and a clear business justification. They train purchasing staff to recognize the red flags called out by marketplace veterans: mismatched locations and shipping times, stock photos, unrealistic pricing, and evasive return policies.

They also treat traceability as a requirement. Catalog numbers, serial numbers, supplier names, and invoices are recorded against assets in the CMMS or OT asset management system. When something fails prematurely, the team can trace the part back to its source and make informed decisions about whether the issue is a one‑off defect or a systemic problem with a particular supplier or channel. That traceability can be invaluable when dealing with Rockwell support, especially in light of Rockwell’s own emphasis on OT security and supply‑chain trust.

The final habit is cultural. Successful organizations remind project teams that saving a few dollars per module is not worth introducing an unbounded reliability and safety risk. They use the case studies from Rockwell and others as cautionary tales, making it clear that gray‑market bargains that go wrong will be treated as process failures, not clever cost savings.

Short FAQ

Does registering my Rockwell product online prove it is genuine?

No. Product registration helps Rockwell and its distributors track ownership for warranty and asset purposes, but forum discussions and Rockwell’s own wording indicate that registration is not the same as a formal authenticity check. Use registration as one tool among many, not as your sole test of genuineness.

Can I trust the QR code or barcode on the box as an authenticity guarantee?

Codes on the box are useful for identifying catalog numbers, serial numbers, and configuration options, and they support traceability. However, counterfeiters routinely copy or forge labels and codes. Treat any label or code as data to be checked against trusted documentation and purchase records, not as an unforgeable security feature.

Are all online marketplace sellers unsafe for Allen‑Bradley parts?

Not all, but the risk is significantly higher than with Rockwell and authorized distributors. Long‑standing surplus sellers with clear photos, honest condition descriptions, and robust return policies can be valuable sources, especially for obsolete parts. Nonetheless, the safest assumption is that every “new” Allen‑Bradley listing on a generic marketplace is suspect until you can prove otherwise using the seller’s history, documentation, photos, and post‑delivery inspection.

Closing

In industrial automation, authenticity is not about logo graphics; it is about trust in the behavior of every component when the plant is running hard. As a systems integrator and project partner, my advice is simple: use Rockwell’s authorized channels wherever you can, treat gray‑market deals with deep suspicion, and back your engineers by giving them the authority to refuse hardware that does not have a clean, verifiable story. The cheapest path to project success is almost always the one that keeps counterfeits out of your cabinets in the first place.

References

- https://www.eng.auburn.edu/~uguin/pdfs/GOMACTech2013.pdf

- https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2014ITR....63..468S/abstract

- https://hammer.purdue.edu/ndownloader/files/20076845

- https://dforte.ece.ufl.edu/research/detection-and-avoidance-counterfeit-ics/

- https://web.calce.umd.edu/general/education/CF%20Class.pdf

- https://personal.utdallas.edu/~gxm112130/papers/itc13a.pdf

- https://www.ll.mit.edu/sites/default/files/publication/doc/2018-04/2016-03-16-Koziel-GOMAC.pdf

- https://www.plctalk.net/forums/threads/how-to-verify-genuine-authentic-allen-bradley-ab-hardware-product-by-its-box-label-online.147000/

- https://blog.softwaretoolbox.com/video-tutorial-controllogix-ethernet-topserver

- https://ese-co.com/knowledge/why-register-your-rockwell-products

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment