-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

VFD Price vs Performance Analysis: Finding the Right Balance

After enough years in motor rooms and MCCs, you stop asking whether variable frequency drives (VFDs) save energy. The better question is: which VFD is worth paying for on this specific motor, in this specific process, over the next ten years?

That is the heart of VFD price versus performance. Not the catalog price on one line and the efficiency number on the next, but how the whole drive–motor–process system behaves and pays you back over its life.

In this article I will walk through how I actually evaluate VFDs on real projects: what drives cost, what “performance” really means beyond a glossy efficiency number, where premium drives earn their keep, and where a simpler solution is the smarter buy. Throughout, I will lean on documented findings from sources such as the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, AHRI, the Hydraulic Institute, the International Energy Agency, and major OEMs, rather than marketing folklore.

What Price vs Performance Really Means for VFDs

In many industrial and commercial facilities, motor-driven systems routinely consume on the order of 60% of total electricity. Multiple independent studies, including work cited by the U.S. Department of Energy and NREL, have shown that properly applied VFDs on variable-torque loads like pumps and fans often cut that motor energy use by roughly 20–50%, and in some cases up to about 70%. That is the performance side: energy reduction, better process control, and lower mechanical stress.

On the price side, engineers quickly discover that there is no fixed “VFD price.” Cost swings with horsepower, voltage, enclosure rating, feature set, brand, and market conditions. A bare-bones panel-mount drive may look cheap, but once you include harmonic mitigation, a NEMA enclosure, integration hours, and commissioning time, the total installed cost can easily double or triple the drive list price.

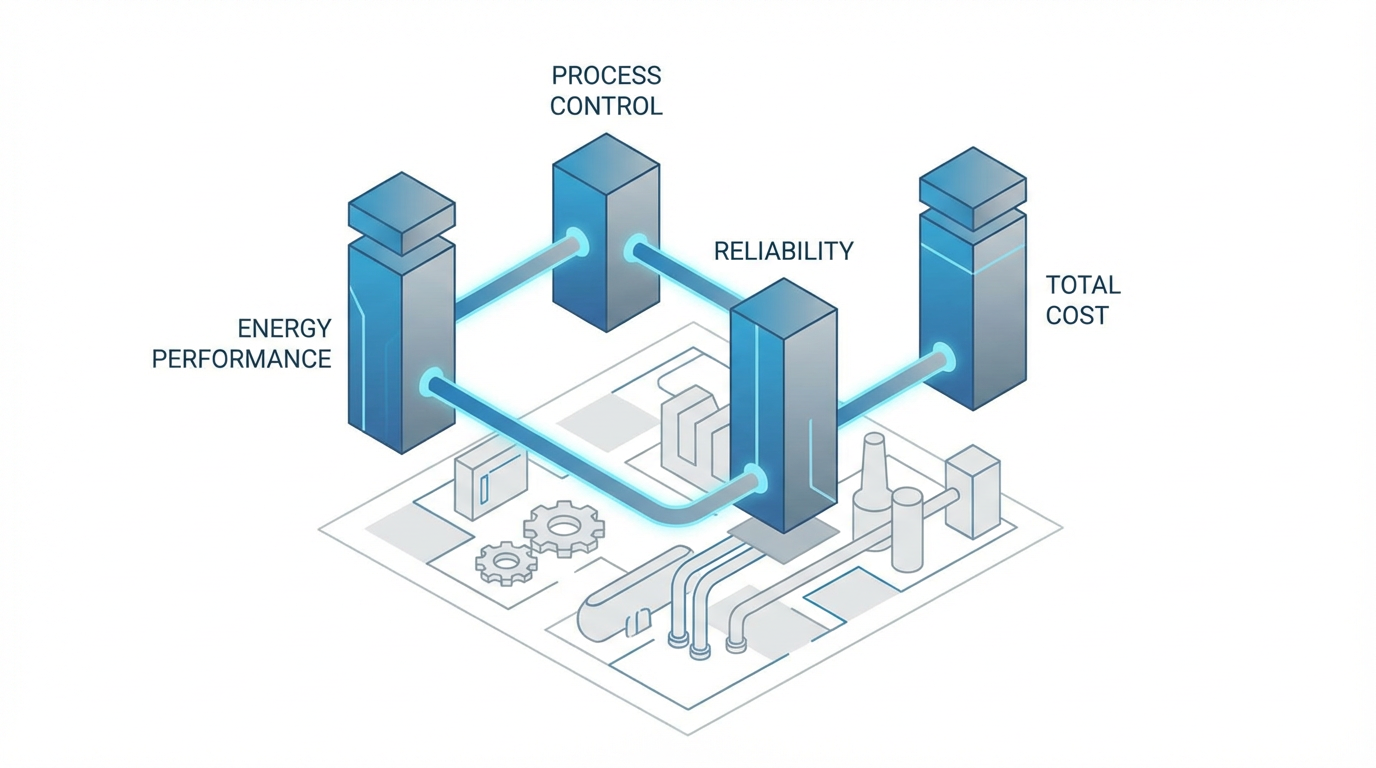

So VFD price versus performance is not a single ratio. It is a balancing act among at least four dimensions:

First, energy performance, meaning how much electricity a drive can realistically save versus the existing control method.

Second, process performance, meaning how well it holds setpoints, responds to disturbances, and supports the quality or throughput your operation needs.

Third, reliability and maintainability, meaning how often you expect the drive or motor to fail, how it behaves under harsh conditions, and how easy it is to support in the field.

Fourth, total cost of ownership, meaning purchase and installation, ongoing energy and demand charges, maintenance, and eventually replacement.

The only way to find the right balance is to make those dimensions explicit and quantify what you can, instead of buying whichever drive has the lowest line item on a bid tab.

A Short Primer: What a VFD Actually Does

A VFD is a power-electronic controller that adjusts the frequency and voltage supplied to an AC motor so you can control its speed and torque. Most modern drives use a pulse width modulation front end: they rectify incoming AC power to DC, smooth it, then recreate an AC waveform by rapidly switching semiconductor devices. By varying the pulse pattern, the drive delivers an effective output at whatever frequency and voltage the control logic demands.

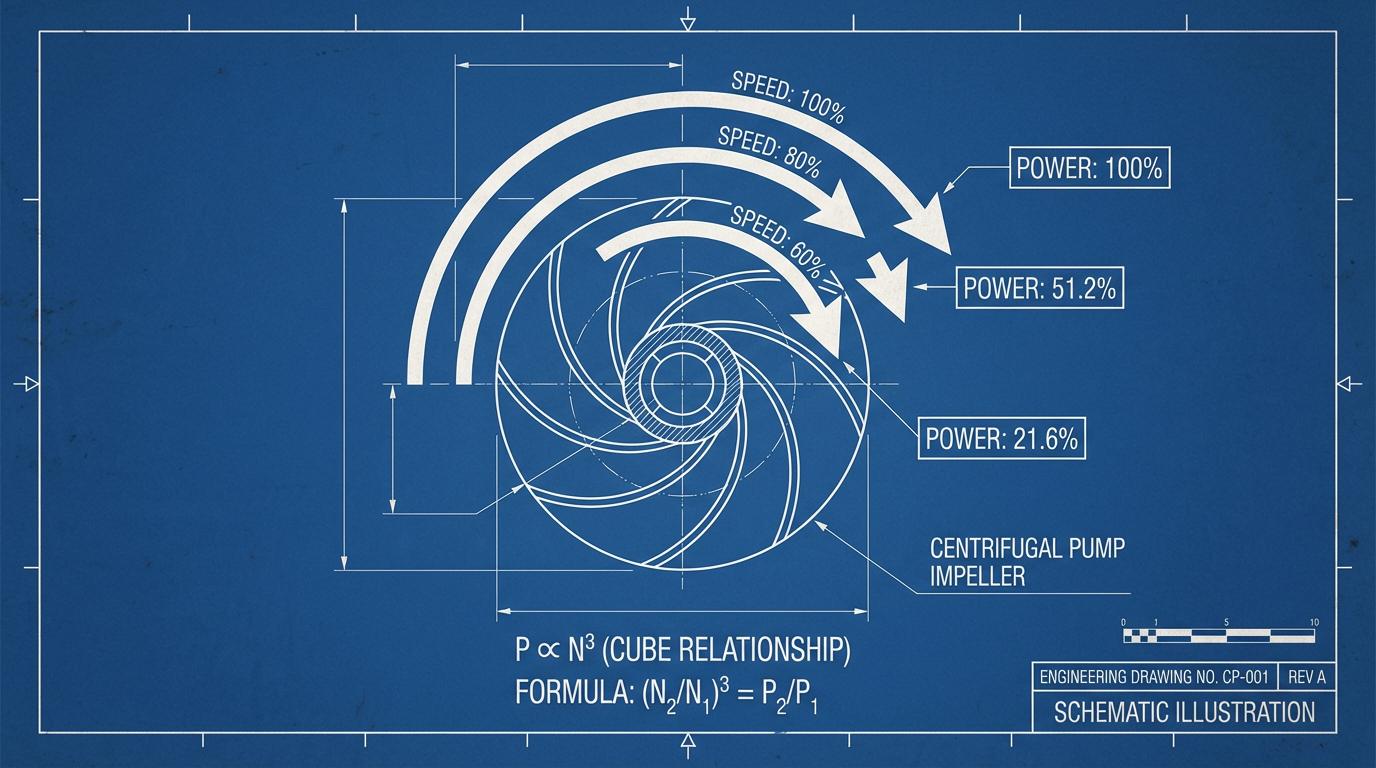

For centrifugal pumps and fans, the affinity laws tell us that power varies roughly with the cube of shaft speed.

If you can reduce speed from 100% to 80%, power draw can drop by around 50%. This is why bodies like the U.S. Department of Energy and the International Energy Agency repeatedly highlight VFDs as a primary efficiency measure for variable-flow pumps and fans. Throttling a constant-speed pump with a valve wastes energy as pressure loss; slowing the impeller with a VFD avoids creating the excess pressure and flow in the first place.

For constant-torque and positive displacement loads, the story is different. Torque does not fall with speed in the same way, so the energy benefit may be smaller. In those applications, the performance value of a drive often comes from soft start, precise torque control, or process flexibility rather than huge kWh reductions.

The True Cost of a VFD: Beyond the Price Tag

Purchase and installation cost drivers

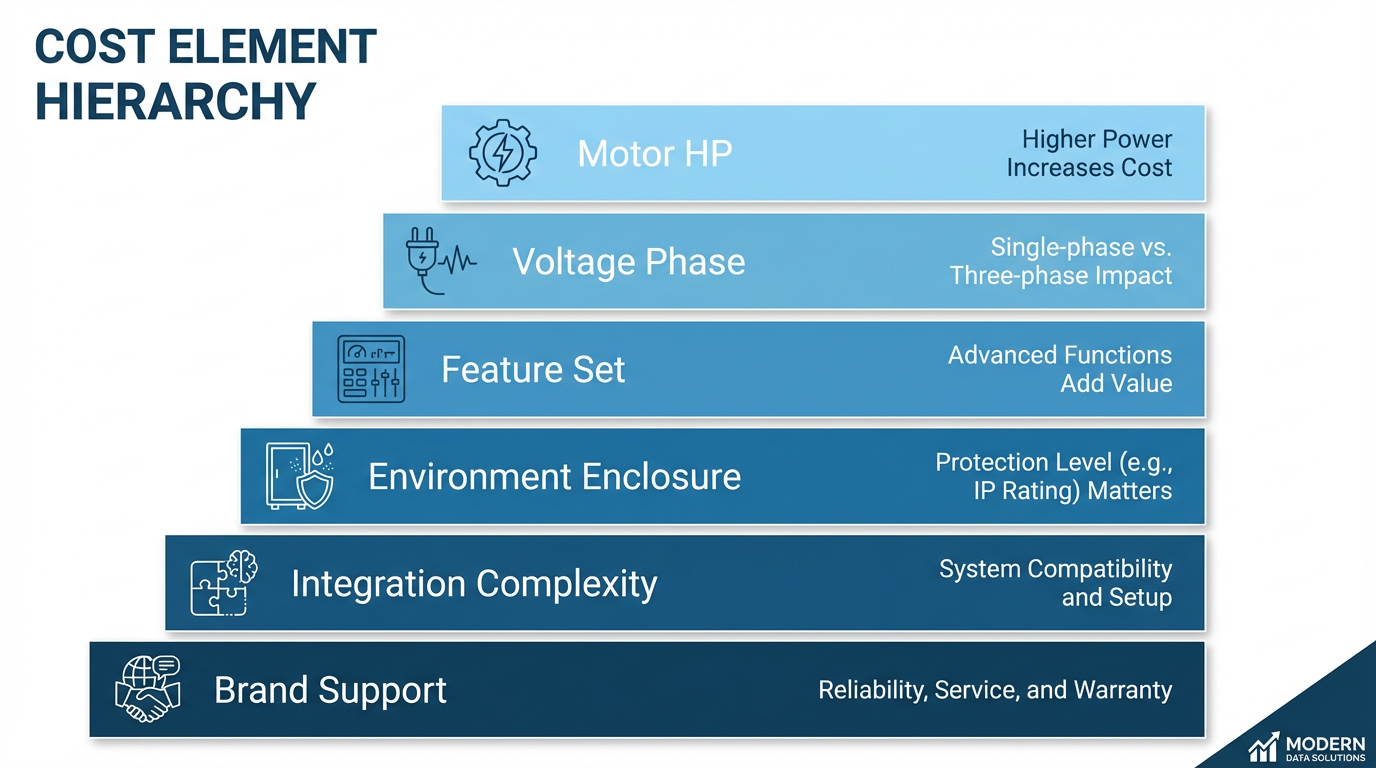

Manufacturers such as Mingchuan and others have laid out the main factors that drive VFD pricing, and they align well with what I see on projects.

Horsepower and load profile come first. Higher horsepower drives cost more, and difficult load profiles drive upsizing. A ten horsepower pump on a straightforward variable-torque duty might be fine with a ten horsepower drive. The same motor on a high-inertia mixer or a conveyor with frequent starts and high peak torque can justify a larger, more capable drive. Undersizing to save a few hundred dollars up front is a good way to buy nuisance trips, overheating, and reduced drive life.

Voltage and phase also matter. Three-phase 480 V-class drives generally cost more than small single-phase units, because they carry more robust rectifiers, filtering, and protection. Drives that can accept a wide range of input voltages or support both single-phase and three-phase inputs add flexibility, and that flexibility shows up in price.

Features are a major differentiator. Basic drives provide simple speed control and local keypad operation. Higher-priced models add internal PID control, torque-boost functions, regenerative braking, multi-motor coordination, and industrial communication options like Modbus, CAN-based buses, or higher-level industrial Ethernet. Those features can reduce the need for separate controllers, contactors, and field wiring, and in many cases they reduce commissioning and maintenance time.

Environmental protection and mechanical design are another cost lever. A simple open-type chassis drive in an existing climate-controlled panel costs less than a NEMA 4X or IP65 stainless enclosure designed for a washdown or corrosive environment. Wall-mounted or floor-standing packaged drives that include disconnect switches, fuses, filters, and convenience terminals raise the capital cost but can significantly reduce field labor and future service complexity.

Finally, brand and after-sales support carry a premium. Well-established brands often charge more, but they also provide better documentation, broader inventories, and more stable product families. For long-lived plants where you will be replacing drives piece by piece over a decade, that stability has real value.

You can think of these influences in a simple way:

| Cost Element | What Changes | Typical Impact on Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Motor horsepower and load duty | Higher hp, heavy starts, constant-torque loads | Drives get larger and more robust |

| Voltage and phase | Higher voltage, three-phase, multi-voltage capability | More complex power stage and protection |

| Feature set | Advanced control, communications, braking, multi-motor functions | Higher list price, potential savings elsewhere |

| Environment and enclosure | Outdoor, dusty, hot, or washdown locations | Upgraded enclosures and coatings increase cost |

| Integration complexity | Harmonic filters, reactors, control integration, cabling | Extra hardware and engineering hours |

| Brand and support | Strong support network and documentation | Price premium but lower lifecycle risk |

Hidden project costs

The drive itself is only part of the price. Real projects accumulate additional costs that are easy to overlook in early budgeting.

You need correctly sized feeders and motor cables, often with shielded construction to handle high-frequency switching. You may need input reactors or harmonic filters to meet power-quality limits. Motors that are not rated for inverter duty can require upgrades or additional bearing protection.

Control system integration is frequently underestimated. Tying the drive into your existing PLC or building management system, configuring signals and alarms, and commissioning control loops can take more man-hours than physically mounting the drive. Operator training, documentation, and spare-parts strategy add more.

Finally, there is the cost of downtime during installation. In production plants that cannot easily pause, the lost throughput during a shutdown window can dwarf the hardware cost. That is why packaged, “plug-and-play” drives that cost more up front sometimes win on total project economics: they reduce installation time and risk.

Lifecycle energy cost

Most lifecycle cost analyses show that energy and demand charges dominate total ownership cost for high-hours, variable-load applications. Several studies and case collections mirror this conclusion.

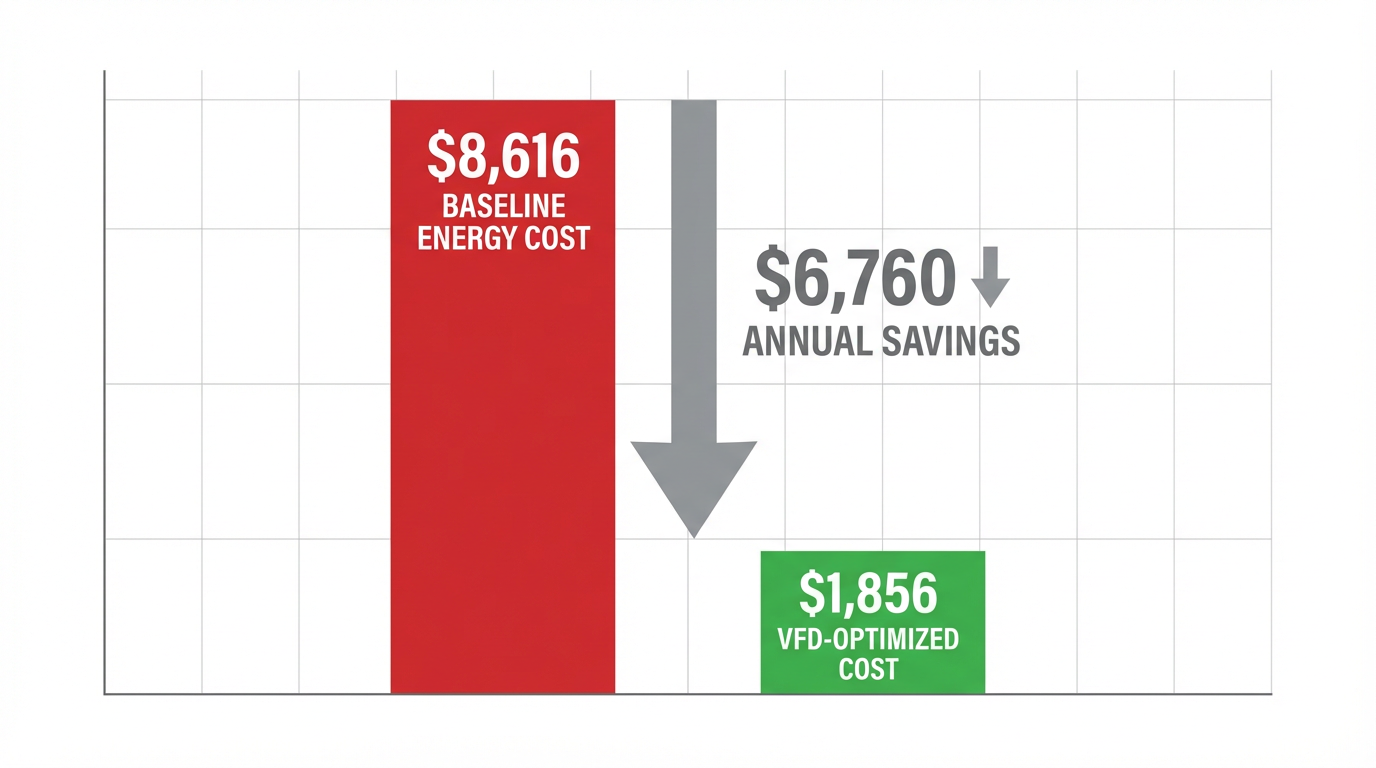

A U.S. Department of Energy study at a water treatment plant found that replacing constant-speed motor starters with VFDs that modulated pump speed to actual flow demand cut energy use by up to about 50%. A Schneider Electric case study on a commercial HVAC system reported about a 35% reduction in building energy use after adding VFD-based fan control. A broader NREL analysis across industrial applications found typical energy-cost reductions between about 10% and 70%, with simple paybacks sometimes as short as one year, depending on duty cycle and electricity prices.

Rohde Bros. presented a practical example using a 10 horsepower pump running nearly all year. With the pump operating at full speed without a VFD, annual electricity cost was estimated around $8,616.00. With a VFD allowing lower average speed, operating cost dropped to about $1,856.00 per year. That produced roughly $6,760.00 in annual savings against an assumed drive purchase of about $2,000.00, leading to a simple payback under a year, even before incentives.

Those are ideal cases with good matches between load profile and VFD control. The point is not that every drive will pay back in twelve months, but that energy is usually the largest line item over the life of a drive system. Focusing only on the purchase price misses the bigger financial picture.

Performance: More Than Just Efficiency Numbers

Drive and system efficiency in the real world

High quality VFDs are efficient devices. Experimental work in HVAC applications has shown that many drives operate around 95–97% efficient at rated load, with only a slight drop in efficiency as load decreases down to roughly a quarter of rated power. That sounds ideal, but that is not the full system story.

The VFD itself introduces conversion losses, typically on the order of 3–5% of input power. In addition, the pulse-width-modulated output voltage and current contain electrical harmonics. These harmonics create extra iron losses in the motor core and copper losses in the windings. Experimental reports indicate that under VFD operation at rated load, motors can experience additional losses on the order of 0.5–1.5% of input power compared with direct-on-line operation, due to harmonic effects.

Taken together, research summarized under AHRI’s performance rating work suggests that combined motor–drive “drive system” efficiency might degrade by roughly 3.5–6.5% from an idealized motor-only efficiency number. This is why standards such as ANSI/AHRI 1210 exist: to provide a standardized method for rating VFD performance in a way that reflects realistic system behavior rather than idealized component data.

On top of that, as Bentley’s pump-efficiency analysis points out, drives have a “parasitic” energy demand that becomes proportionally more important at reduced speeds. Stand next to a heavily loaded drive on a low-flow night and you can feel the heat being dissipated. That heat is energy purchased from the utility that is not doing useful work.

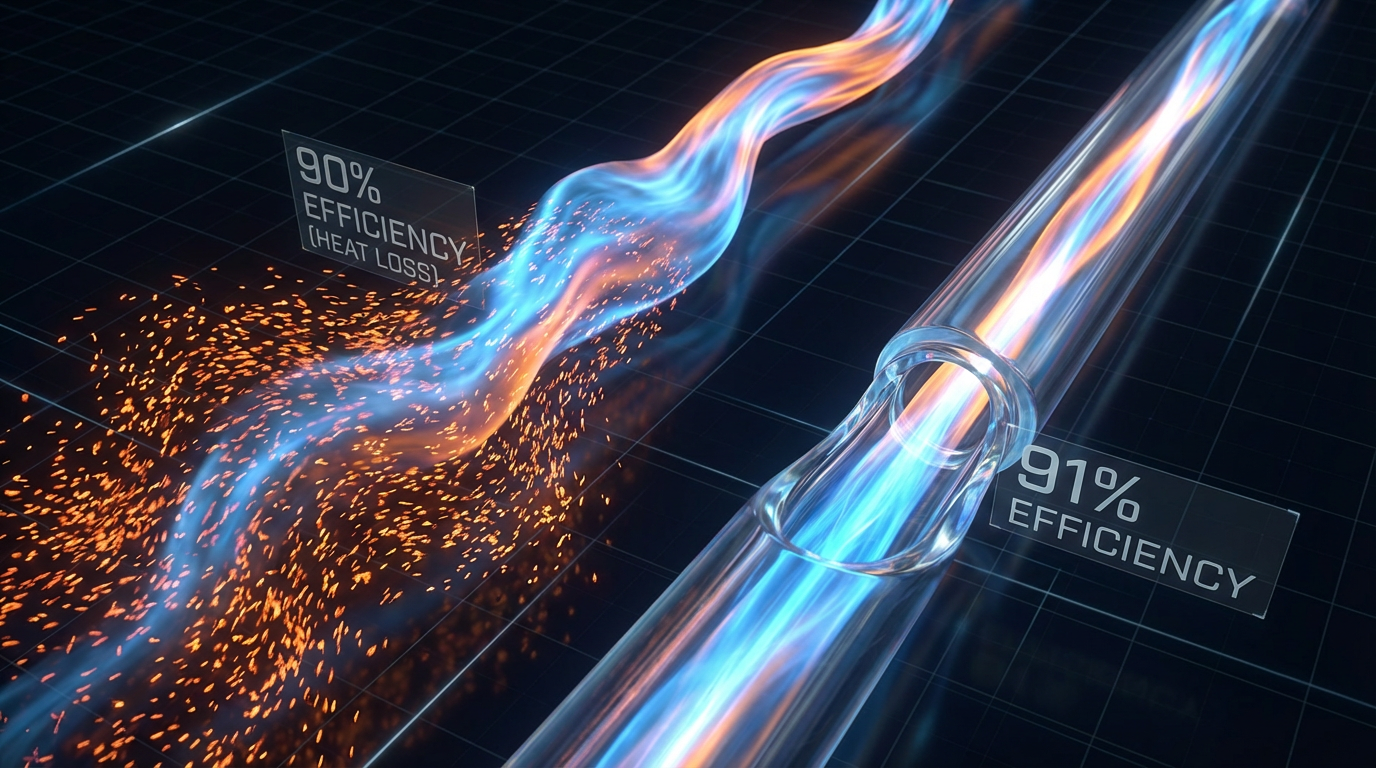

The implication for price versus performance is clear: a slightly higher-efficiency drive can have real financial value on large, high-hours loads. Rockwell Automation has illustrated this with an example: for a 100 kW application operating at a 60% duty cycle over roughly seven years, improving combined motor–drive efficiency from 90% to 91% reduces lifetime energy use by about 41,000 kWh. At $0.10 per kWh, that single percentage point buys roughly $4,100.00 in savings over the VFD life.

On a large plant, those incremental gains add up quickly.

Process performance and controllability

Energy efficiency is only one aspect of performance. In many of the systems I commission, process performance is just as important.

VFDs provide precise speed and torque control. In variable air volume HVAC systems, for example, they let you modulate fan speed to match real-time airflow demand instead of relying solely on inlet vanes or dampers. Research on VAV systems in hospitals has shown that switching from mechanical throttling to fan speed control can reduce fan energy by about 5–30%, but the bigger operational gain is the ability to maintain comfort and ventilation targets across a wide range of operating conditions.

In pumping applications, modeling tools such as Bentley’s OpenFlows Water or similar hydraulic analysis software can simulate system head curves over time and identify the best combinations of pump speed and staging to minimize energy while maintaining pressure. VFDs are the actuators that make those optimized control strategies possible.

Drives also deliver soft start and soft stop. Instead of hitting a motor with 500–600% inrush current on a direct-on-line start, a VFD can ramp frequency and voltage so that starting current peaks around 150% of full-load current. The Hydraulic Institute has documented how this reduced electrical and mechanical shock translates into longer bearing life, fewer coupling failures, and less pipe stress, especially in rotodynamic pump systems.

Reliability and power quality

Reliability is where cheap drives usually get found out.

Illinois Electric and other reliability-focused firms describe VFD reliability in terms of metrics such as mean time between failures (MTBF), combined with environmental testing, component-level analysis, and accelerated life testing. Drives are subjected to thermal cycling, vibration, humidity, and dust to expose design weaknesses.

Component tests focus on capacitors, power semiconductors, and cooling systems. Accelerated life testing pushes devices beyond normal stress levels to reveal failure modes quickly. All of that data feeds into reliability predictions.

Field data then either validates or contradicts the lab picture. Real drives operate in hot control rooms, dusty mills, and damp mechanical spaces. They see lightning strikes, voltage sags, and operators bypassing safety alarms. Vendors who invest in collecting and analyzing field data can refine their designs for real-world robustness. That is part of what you pay for when you choose a more established brand.

Power quality cannot be ignored either. Drives introduce current and voltage harmonics. Most electrical equipment is designed to tolerate only a limited voltage total harmonic distortion, often around 5%. Where plant power-quality limits are tight or sensitive equipment is present, you may need line reactors, harmonic filters, or multi-pulse or active-front-end drives. Those add cost but prevent nuisance trips, transformer overheating, and other headaches.

In short, performance includes how the drive behaves on a bad day, not just during a lab test. Paying for higher reliability and better power-quality mitigation is part of the price versus performance calculus, especially in critical systems.

When Paying More for a VFD Actually Pays Off

From a systems integrator’s standpoint, the premium drive wins when three conditions line up: a large, long-running, variable-load motor; a process that benefits from fine control; and either high energy prices or high cost of downtime.

In many retrofits, the obvious candidates are chilled-water pumps, condenser pumps, cooling tower fans, large supply and return fans, and big process blowers. These are variable-torque loads with long operating hours and significant time at partial load. Studies cited by the Uniform Methods Project and by utilities show that VFD retrofits on these applications routinely achieve energy savings in the 20–50% range.

The payback math is straightforward if you follow accepted methods. The U.S. Department of Energy’s Uniform Methods Project recommends characterizing a clear baseline: constant-speed operation, existing throttling method, operating hours, load profile, and control strategy. Measurements of motor power, speed, and key process variables over representative periods build that baseline.

After installing the VFD, you log the same variables and derive new power-versus-load relationships. For variable-torque loads, baseline power might vary roughly linearly with flow under throttling, while VFD power varies more like the cube of speed. Combine the two sets of curves with measured or estimated distributions of load and operating hours over a year. The difference in annual kWh, multiplied by your blended electricity rate, is the annual dollar savings.

Methods described in engineering discussions, including practical guidance on using current loggers and simple duty-cycle approximations, point out that you can get decent savings estimates even with limited instrumentation, as long as your assumptions are transparent.

The upshot, reinforced by case studies from system integrators and OEMs, is that for well-chosen loads the higher price of a robust, efficient VFD is usually repaid quickly through reduced energy use and lower mechanical stress. That makes the real performance metric not just “percent efficiency,” but “net present value of avoided energy, maintenance, and downtime over the drive’s life.”

When a Cheaper Drive or Traditional Starter Is Enough

Not every motor needs a VFD, and not every VFD needs to be a premium model.

Traditional motor starters and contactors still make sense on genuinely fixed-speed, low-variability loads where energy savings potential is minimal, duty cycle is low, and process control demands are modest. System control specialists point out that in these cases, a traditional starter may have higher lifetime energy and maintenance costs than a VFD, but the absolute numbers are small enough that the economics do not justify the additional capital and complexity.

Even when you decide on a VFD, there are plenty of cases where an entry-level or mid-range drive is the right answer. An exhaust fan that runs intermittently for odor control, or a small conveyor with simple start–stop and minimal speed trimming, may not warrant advanced harmonics mitigation, high-end torque algorithms, or integrated web servers.

You can think of drive choices in broad tiers.

| Drive Tier | Typical Features | Where It Makes Sense |

|---|---|---|

| Entry-level | Basic V/Hz control, keypad, limited I/O | Small pumps, fans, or conveyors with simple speed trimming |

| Mid-range | Enhanced control, basic communications, better diagnostics | Core plant utilities, moderate integration needs |

| High-performance | Advanced torque control, rich communications, strong M&V | Critical processes, large hp, tight energy and reliability goals |

The price jumps from entry-level to high-performance are real. The trick is matching the tier to the application, not defaulting to the cheapest catalog number or the most feature-rich option just because it is available.

A Practical Framework for Balancing Price and Performance

When I am asked to recommend drives on a plant-wide upgrade, I follow a fairly consistent framework.

First, I map the motor inventory and duty. That means identifying the big energy users: large horsepower motors, long operating hours, and variable-torque loads. Motors that barely run do not drive the business case, even if the efficiency gain on paper looks attractive.

Second, I quantify baselines where it matters. That may be as simple as logging current over a few weeks on a pump running under valve control, or as detailed as a full motor power and flow profile on a critical process line. The Uniform Methods Project guidance provides a solid template for this step.

Third, I estimate savings potential and payback. Using measured or estimated load profiles, I apply pump and fan affinity relationships and known power-versus-speed behavior to estimate how much a VFD would reduce power at typical operating points. On large projects, I sometimes lean on hydraulic or airflow modeling tools, such as those highlighted in Bentley’s work on water distribution systems, to refine these estimates.

Fourth, I define performance and reliability requirements for each candidate motor. Some applications only need basic speed control and soft start. Others require tight pressure control, fast transient response, or integration into a plantwide automation or building management system. Reliability expectations also differ. A noncritical sump pump can tolerate a lower MTBF than a process air fan feeding a continuous line.

Finally, I select the drive tier and options that match those needs. For each motor or group of motors, I choose whether an entry-level, mid-range, or high-performance drive is justified, then decide on enclosure, filtering, communications, and protection options. At this point, total installed cost and lifecycle energy savings are compared side by side.

This is also the stage where I decide where to spend extra for efficiency. On a large, high-hours motor, stepping up to a drive that offers slightly better efficiency, verified through standards such as IEC 61800-9-2 and AHRI rating methods, can be worth the premium. Rockwell Automation’s life-cycle analysis example shows that even a single percentage point of system efficiency can be worth thousands of dollars over a drive’s life at industrial scales.

Throughout, I document assumptions and align with the plant’s financial language. Simple metrics such as payback period, internal rate of return, and net present value help stakeholders see why a more expensive drive is actually the low-risk choice over time.

Reliability, Testing, and Choosing “Good Enough”

One fear I still hear from operators is that VFDs add complexity and become single points of failure. That concern is valid if you treat drives as a commodity and ignore reliability data.

Reliability-focused articles and vendor documentation outline the standard toolkit: MTBF estimates based on field data, environmental testing under temperature, humidity, dust, and vibration, component-level qualification of capacitors and semiconductors, and accelerated life testing to identify early failure modes. Serious manufacturers back this up with real field monitoring and predictive maintenance tools.

From a price versus performance standpoint, you are paying not just for a box of electronics, but for the engineering and field experience behind it. Drives that have undergone rigorous environmental testing and component analysis, and whose MTBF is supported by actual field data, are more likely to survive in hot, dirty, real-world environments. That is particularly important in applications where a failed drive halts production or compromises safety.

At the same time, overbuying is possible. Installing a premium, feature-rich drive with extensive communications and diagnostics on a small, noncritical fan can be unnecessary. In those cases, I still look for basic reliability markers and a solid support channel, but I do not pay for every available feature.

The goal is not the “best” drive on paper, but the drive that is sufficiently robust and capable for the application, with a sensible balance of upfront cost and lifecycle risk.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does a one or two percent efficiency difference between drives really matter?

On a small, lightly used motor, probably not. On a large, continuously running system, absolutely. Rockwell Automation has demonstrated with a 100 kW example that increasing combined motor–drive system efficiency from 90% to 91% over a typical seven-year drive life can cut energy use by roughly 41,000 kWh. At an electricity rate of $0.10 per kWh, that is about $4,100.00 in savings. On larger installations with multiple drives, those incremental gains stack up. This is why it can be worth paying for a higher-efficiency drive on big, high-hours loads, especially where electricity is expensive.

How should I talk about VFD projects with finance or management?

Finance teams care about risk and payback, not about control algorithms. The most effective conversations start with measured data and standard methods. Use baseline logging or credible estimates to show current energy use and operating patterns. Apply recognized methods, such as those from the Uniform Methods Project or well-documented case studies, to estimate post-VFD energy use. Present the incremental cost of the drive system, including installation and any required motor or power-quality upgrades, alongside the expected annual savings, simple payback, and net present value. When you include non-energy benefits such as reduced maintenance and longer equipment life, VFD projects that are well targeted usually compare favorably to many other capital investments.

Closing Thoughts

If there is one lesson from years of VFD work, it is that you rarely regret specifying a drive carefully, but you often regret buying one solely on price. The right VFD is not necessarily the most expensive model on the market; it is the one whose cost, efficiency, control capability, and reliability align with what your motor and process actually need. Approach drives with the same rigor you apply to process design and safety, and they will pay you back for years as quiet, reliable partners in your plant’s performance.

References

- https://docs.nrel.gov/docs/fy17osti/68574.pdf

- https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/2576741

- https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2015/01/f19/UMPChapter18-variable-frequency-drive.pdf

- https://www.pumps.org/pump-pros-know-variable-frequency-drives/

- https://www.ahrinet.org/system/files/2023-06/AHRI_Standard_1211_SI_2019.pdf

- https://www.aceee.org/files/proceedings/1999/data/papers/SS99_Panel1_Paper49.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324810181_Performance_assessment_of_variable_frequency_drives_in_heating_ventilation_and_air-conditioning_systems

- https://d3mm496e6885mw.cloudfront.net/manufacturer_product/5919d9d2e4b0b6f46aff2a4b/project/projects/original/Cost_Considerations_VFD_FINAL.pdf

- https://systemcontroltech.net/2023/07/25/variable-frequency-drives-vs-motor-starter-relays-a-comparative-analysis-of-energy-and-cost-savings-for-electric-motors/

- https://www.newark.com/how-to-save-energy-and-costs-with-a-variable-frequency-drive-trc-ar

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment