-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Specifying a 32-Point Output Module for Large-Scale Control Applications

When you scale a control system from a few dozen I/O points to several thousand, 32-point output modules stop being catalog curiosities and become the backbone of your architecture. As a systems integrator, I have seen entire packaging halls, bottling lines, and building complexes hinge on whether those high-density modules were specified correctly and verified rigorously. Get the specification right, and you gain compact panels, predictable behavior, and maintainable code. Get it wrong, and you will be chasing intermittent trips, hot cabinets, and unexplained downtime.

This article walks through how to think about a 32-point digital output module for large-scale control, using real data from an Allen-Bradley 1762-OB32T case study, along with guidance from established I/O module and power design practices. The focus is pragmatic: what to look for, why it matters in a big system, and how to document and validate your choice like a professional design output rather than a shopping decision.

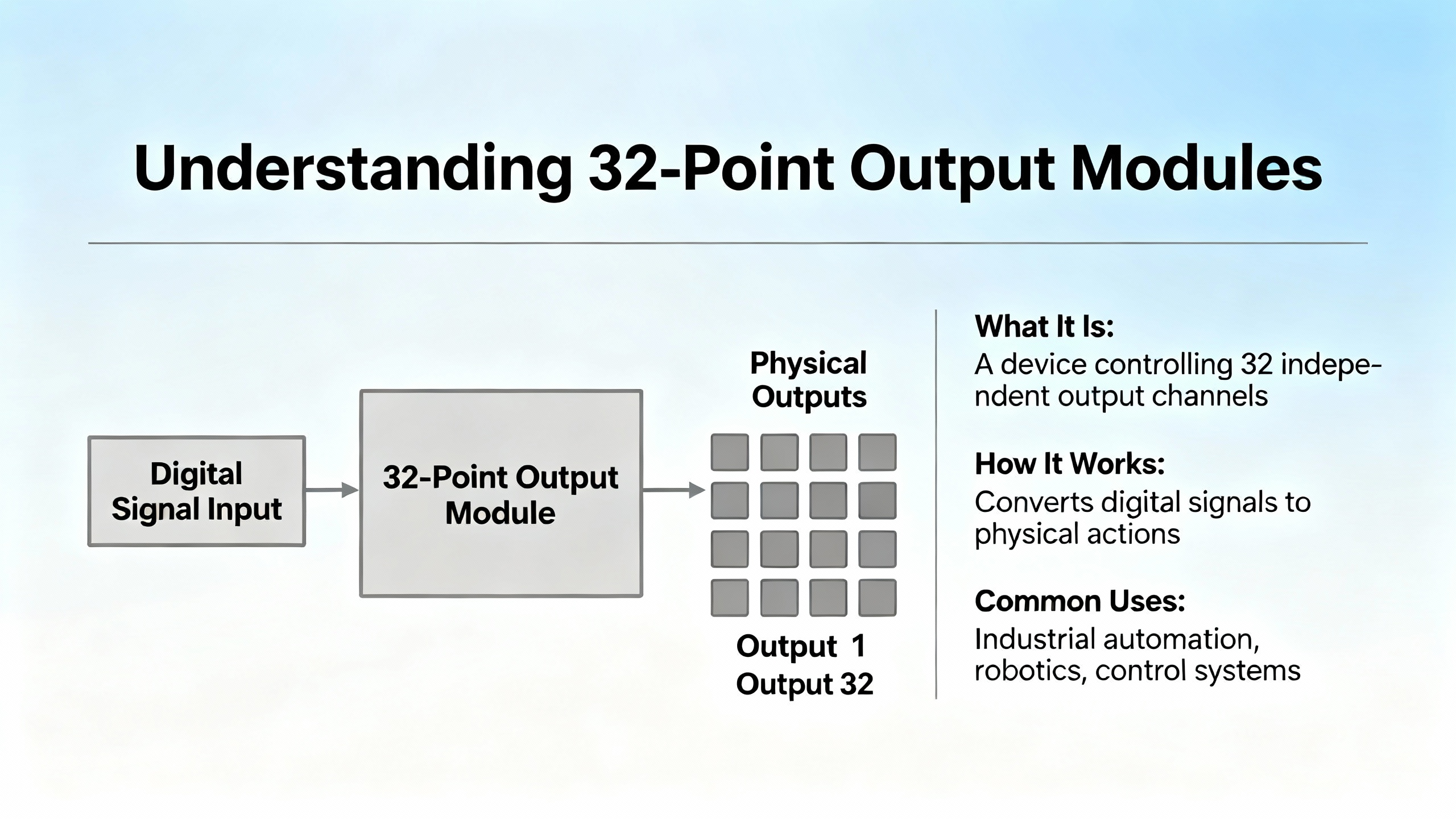

What a 32-Point Output Module Really Is

An I/O module is the intermediary between your controller’s CPU and the real world. As described in guidance from Shoplogix, it handles data transfer, power distribution to the field, and the control of machine functions so the controller can interact with sensors and actuators instead of being an isolated piece of silicon.

Within that broader family, a 32-point digital output module is a device that presents thirty-two discrete output channels to the field. Each channel can command an on or off state to downstream devices such as contactors, indicator lights, or solenoid valves. Unlike analog outputs, which generate continuous values, digital outputs are designed for binary decisions that define distinct equipment states. In modern industrial automation, particularly in material handling, packaging, automotive, and building systems, these modules are central components because they let you pack a lot of control into a relatively small footprint.

In building automation, Johnson Controls describes its I/O modules as point expanders and multiplexors. When these modules sit on a local sensor-actuator bus, they simply expand the available I/O count of a parent controller. When connected on a field-level bus, they can act as I/O point multiplexors, making points available to supervisory controllers and enabling peer-to-peer sharing. The same idea carries over to industrial PLC racks: a 32-point output module both expands the controller’s reach and acts as a structured, addressable block of outputs that you can share across machine zones or higher-level systems.

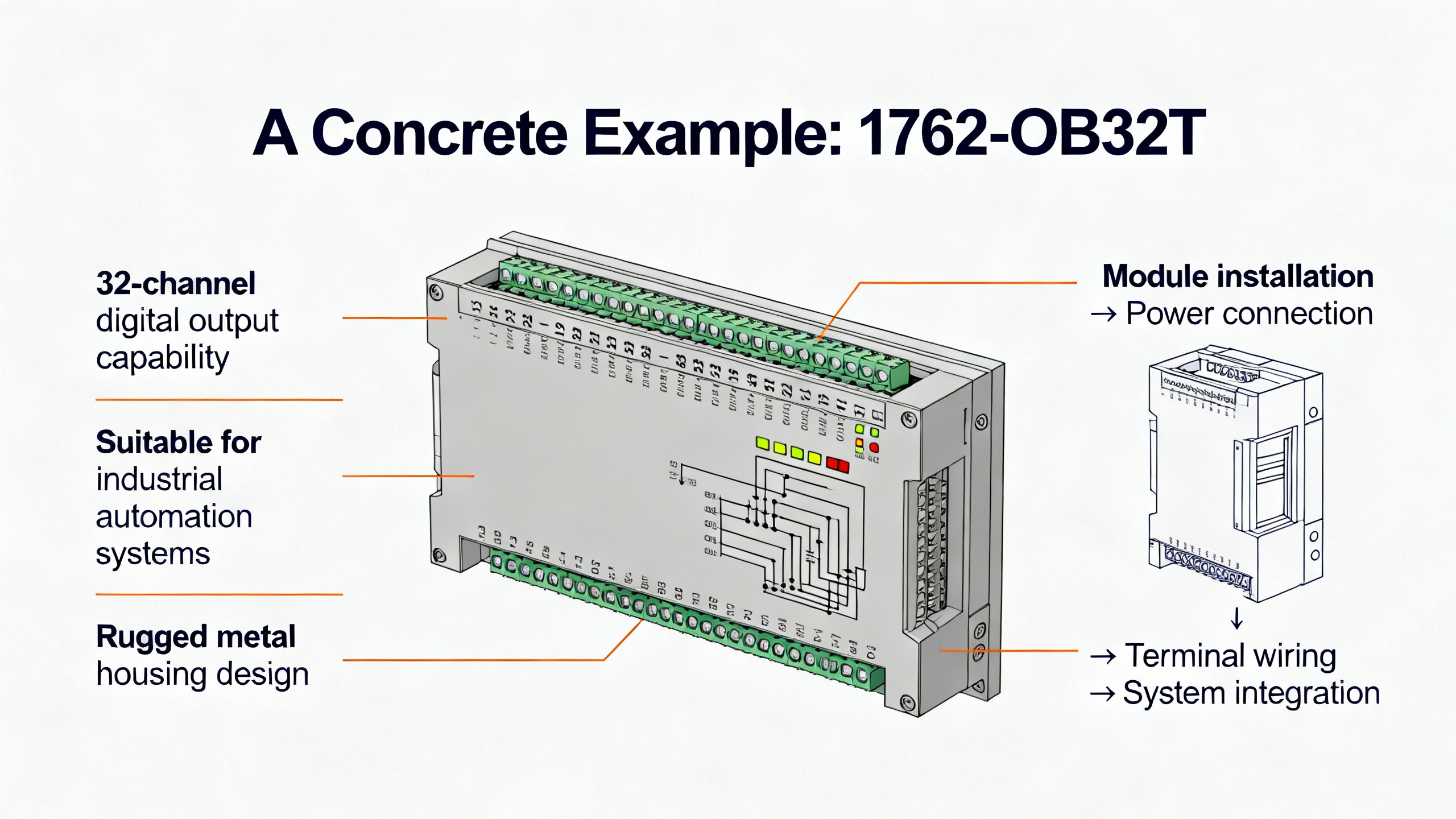

A Concrete Example: Allen-Bradley 1762-OB32T

To get beyond abstractions, it helps to anchor the discussion in a real module. Asteam Techno Solutions describes the Allen-Bradley 1762-OB32T as a DC output module with thirty-two sourcing transistor outputs, designed for MicroLogix 1200 and 1400 PLCs. Its role is straightforward: send electrical signals to external DC-powered devices so the PLC can control when they turn on and off, with an emphasis on speed, stability, and simplicity of integration.

Key technical details for that module include the following characteristics.

| Parameter | Example value (Allen-Bradley 1762-OB32T) | Practical meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Product type | DC sourcing transistor output module | Solid-state outputs for DC loads rather than relays |

| Number of outputs | Thirty-two, arranged as two groups of sixteen | High channel density, with grouped behavior and thermal management |

| Output type | DC, 10/16/24 V sourcing | Suitable for common DC devices such as lights, small motors, and solenoids |

| Minimum output current | 1.0 mA per channel | Ensures reliable detection and operation for low-current loads |

| Maximum output current | 0.5 A per channel | Defines the upper bound for each load on a single point |

| Backplane current | 168 mA at 5 V DC | Draw from the PLC backplane that must be budgeted at system level |

| Isolation voltage | 50 V continuous | Electrical separation between module circuitry and field wiring |

| Dimensions | Approximately 3.54 by 1.59 by 3.43 in | Compact enough for tight panels |

| Operating temperature | 32 to 131 °F | Covers typical industrial cabinet environments |

| Weight | About 0.64 lb including packing | Light enough that panel mechanical loading is negligible |

This module integrates directly into MicroLogix 1200 and 1400 systems, and Asteam Techno notes it can be combined with MicroLogix 1100 and 1400 installations as well, with minimal installation effort. That ease of integration is a recurring theme in high-density modules: the more complicated the wiring and configuration, the more pain you will feel when you scale from one panel to dozens.

Where 32-Point Modules Make Sense in Large-Scale Control

In small machines, sixteen or even eight outputs per module may be enough, and space is rarely the hard constraint. Once you scale into multi-line plants or tall building automation systems, the economics change fast. Shoplogix emphasizes that I/O modules are designed for scalability and modularity, allowing industries such as manufacturing, oil and gas, food and beverage, and life sciences to add or remove modules as needs change with less reconfiguration effort and cost.

In practice, 32-point output modules become particularly attractive in situations such as:

When you have a large number of similar discrete loads. Conveyor zones, diverters, stack lights, and simple on/off valves are classic examples where density matters more than individual channel complexity.

When panel real estate is limited. Asteam Techno highlights the space-saving design of the 1762-OB32T, noting that thirty-two outputs in a compact package reduce the number of modules required and make it easier to fit within tight control cabinets. In large facilities, this often translates to fewer enclosures and lower installation costs.

When you want cleaner architectural boundaries. In a large system you might assign each 32-point module to a well-defined zone: a packaging cell, a filling block, or a building floor. That lines up nicely with modular design principles drawn from software and infrastructure practice, where each module is responsible for a coherent subset of functionality and can be developed and maintained somewhat independently.

The important point is that the decision to use a 32-point module is rarely only about the count. It is about density, architecture, and the long-term maintainability of your wiring, documentation, and control logic.

Electrical Specification Priorities for Large-Scale Control

Once you know a 32-point module makes sense architecturally, the next step is to look hard at the electrical details. In a large system these are not fine print; they are design inputs that will drive your power distribution, wiring methods, and, ultimately, uptime.

Output voltage and type

The 1762-OB32T is specified as a DC sourcing module for 10, 16, and 24 V devices. That aligns with the Shoplogix description of digital I/O modules, which handle discrete binary signals used to read switches or drive actuators. For a large-scale control system, the implications are straightforward. You must standardize your field devices around compatible DC levels, and you must plan the system’s power supplies accordingly.

If your plant has legacy AC loads or mixed-voltage islands, either they need interface relays and power supplies to adapt them to the module, or you need to segregate them on different output modules entirely. Mixing incompatible load types on the same high-density card is a recipe for confusion and field wiring errors.

Channel current and load types

With a minimum output current of about 1 mA and a maximum of 0.5 A per channel, the Allen-Bradley module is positioned squarely for typical PLC-grade loads: indicator lights, pilot relays, small solenoid valves, and compact DC motors. Asteam Techno notes that the module is used in applications such as conveyor control, robotic welding stations, solenoid valve manifolds in pharmaceutical cleanrooms, and smart warehousing systems.

When you scale up, you need to be honest about your load mix. If you intend to drive heavier devices directly, then either those loads need local interposing devices, or you need modules with higher current ratings. Monolithic Power Systems emphasizes the value of derating in power electronics, recommending that components operate below their nameplate capacity to improve life and reduce the chance of failure. The same philosophy applies at the channel level for output modules. Treat 0.5 A as an upper bound, not a design target, and leave margin so you are not running each point at its thermal limit every time a line starts.

Grouping and thermal behavior

The 1762-OB32T divides its thirty-two points into two groups of sixteen, and Asteam Techno points out that this group-based switching helps with thermal efficiency. In practice, that grouping shows up in how internal fusing, power distribution, and fault detection are organized. When you design a large system, you should plan your load distribution so that no group is heavily overloaded relative to the others, and so that critical loads are not all located on a single group that could be lost together in a fault.

This is conceptually similar to the power circuit design principles outlined by Monolithic Power Systems, where thermal management and conduction losses are central concerns. Spreading heat-generating loads across groups reduces local hot spots and improves reliability.

Backplane loading and power budget

Backplane current is often overlooked during preliminary design, and then rediscovered when a fully loaded rack begins to trip its power supply. The 1762-OB32T draws 168 mA from the 5 V backplane. That seems small in isolation, but when you multiply it across ten or twenty modules, plus the base controller and other hardware, it becomes a nontrivial load that must be supplied and cooled.

Vicor’s guidance on modular DC-DC systems stresses designing from the loads back to the source, accounting for all modules and their efficiency. In a control panel, the PLC power supply, backplane ratings, and secondary DC supplies are all parts of the same chain. If you want to use many high-density output modules, you must verify that the backplane can support their combined draw and that the main power supplies have enough current and headroom to keep the system within a comfortable derated operating range.

Isolation and safety

The module’s continuous isolation rating of 50 V creates a defined boundary between field wiring and the PLC side electronics. Shoplogix notes that I/O modules play a key role in operational safety by enabling real-time monitoring and control that supports high product quality and regulatory compliance. Isolation Reinforces that role by limiting the propagation of transients and wiring mistakes into the controller.

In high-density systems, isolation ratings should be treated as hard design constraints. For example, mixing loads that routinely see higher common-mode transients on a module with modest isolation is unwise. Wherever voltages or transients approach those limits, either the module choice or the field protection scheme needs attention.

Form Factor and Panel Design

Physical size often dictates whether your carefully chosen specs can be deployed at all. Asteam Techno calls out the 1762-OB32T’s compact profile as a key benefit, with dimensions on the order of three and one half by one and one half by three and one half inches. That footprint lets you fit substantial output density into relatively small PLC cabinets.

In a large facility, those inches add up. With high-density modules you can reduce the number of enclosures, shorten field cable runs, and free space for future expansions. At the same time, high packing density raises the stakes for thermal management. Monolithic Power Systems emphasizes the importance of heat sinks, airflow, and careful layout to avoid overheating in power circuits. While a PLC rack is not a high-power DC-DC converter, the same logic applies. You must leave enough cabinet volume, airflow paths, and cable management space around stacks of 32-point modules so their heat can be dissipated and their wiring can be serviced without disturbing adjacent circuits.

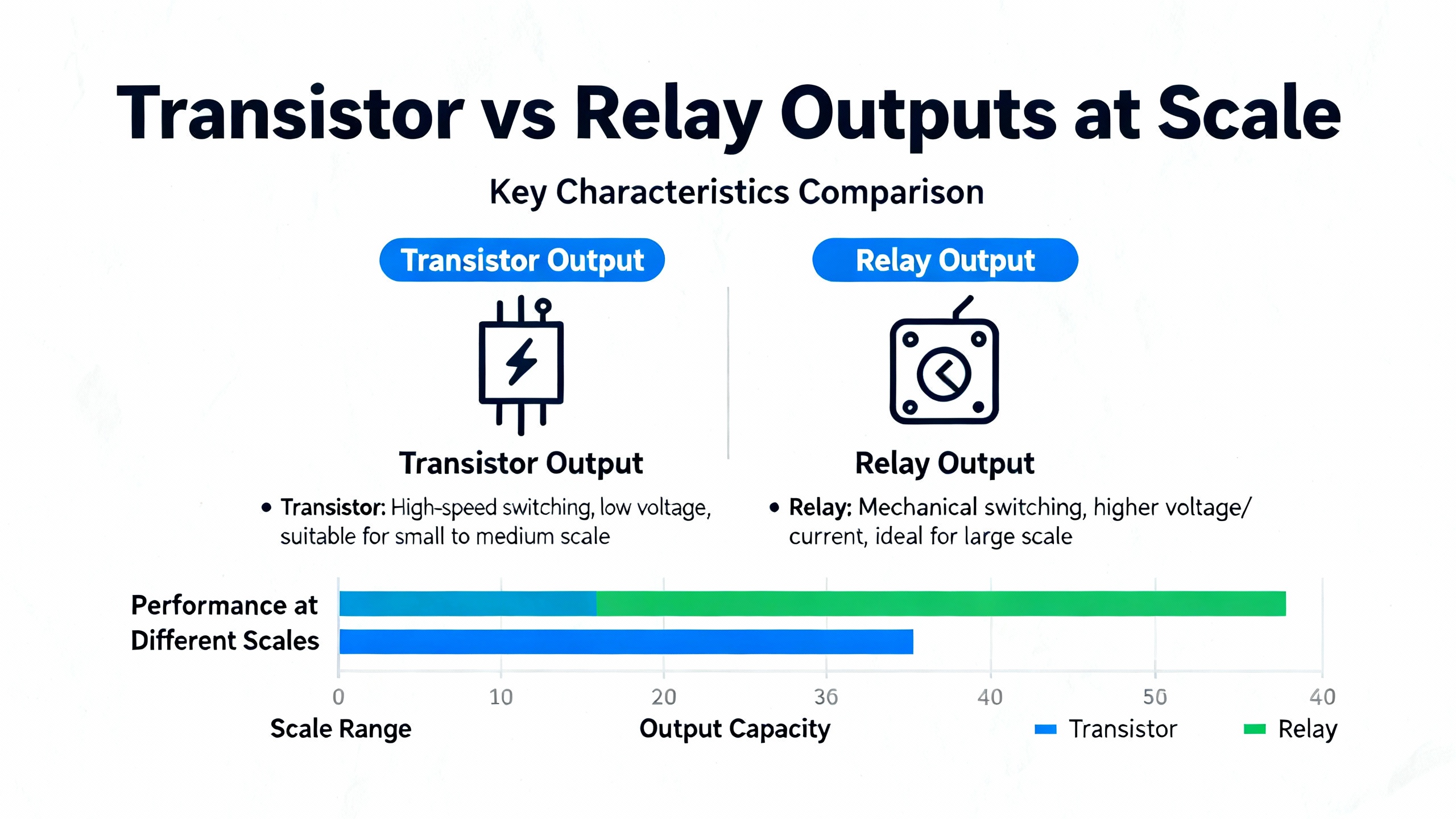

Transistor vs Relay Outputs at Scale

Asteam Techno contrasts the 1762-OB32T’s transistor outputs with traditional relay-based modules, noting that the solid-state design reduces wear and is well-suited to high-frequency switching. That difference matters enormously when you scale up.

In a large plant, high-speed actuators and packaging equipment can switch outputs thousands or tens of thousands of times per shift. Relay contacts are mechanical components and inevitably wear; transistor outputs, by contrast, avoid mechanical contact erosion. The result is fewer field failures, less unplanned maintenance, and more predictable performance under high switching rates.

Relay modules still have their place, especially when you must switch higher voltages or when you need the isolation characteristics of a physical contact. However, when the loads are within the DC ratings of a transistor module, and when switching frequency is high, the transistor option is usually the pragmatic choice. The beverage plant case documented by Asteam Techno illustrates this: when a manufacturer replaced relay-based modules with the 1762-OB32T to control high-speed actuators on a bottling line, downtime dropped by about forty percent and throughput increased by approximately twenty-three percent. For a large site, those percentages translate directly into major capacity and maintenance gains.

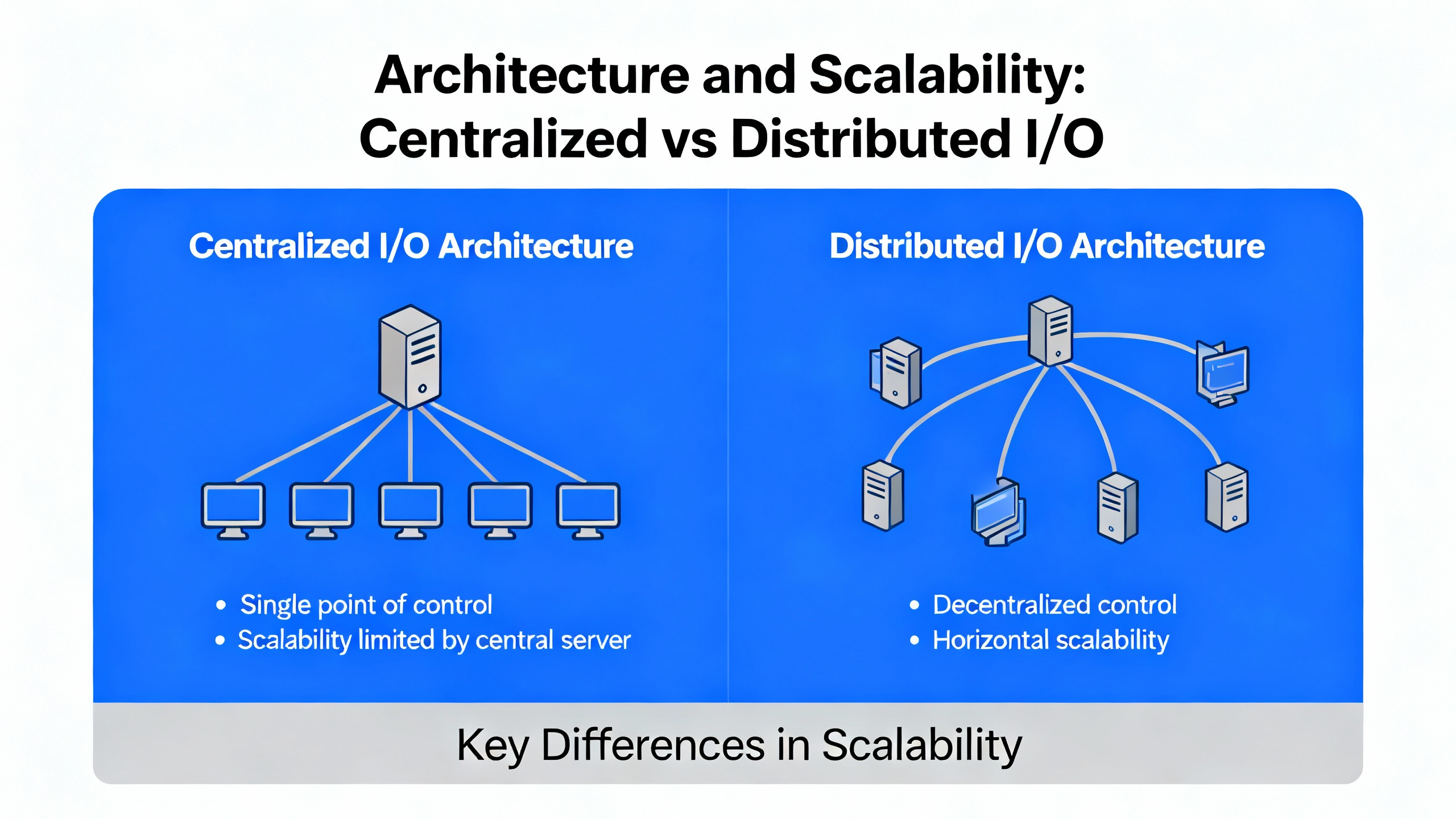

Architecture and Scalability: Centralized vs Distributed I/O

Specifying a 32-point module is not just a catalog choice; it is an architectural decision. Guidance on multi-input and output control systems emphasizes that centralized and distributed architectures each have pros and cons. In a centralized architecture, one controller handles all inputs and outputs, simplifying design but creating potential bottlenecks and single points of failure. A distributed architecture spreads control across multiple controllers that communicate and cooperate, improving reliability and performance at the cost of more complex coordination.

High-density output modules support both models. In a centralized rack, you may load several 32-point cards into a main PLC to keep logic and I/O tightly coupled. In a distributed architecture, you can deploy smaller controllers or I/O processors in the field, each with one or two 32-point modules serving a local zone. Johnson Controls’ description of their I/O modules acting as I/O point multiplexors captures this pattern: modules can expand local controllers on a sensor-actuator bus or be attached to a field controller bus where supervisory devices monitor and control them.

For large-scale systems, I have found that the sweet spot is usually a hierarchical design. Each physical or functional zone gets a local controller with its own I/O modules, and those controllers report to a plant-wide or building-wide supervisory system. In that structure, 32-point output modules let each zone manage a substantial number of actuators without bloating the footprint or forcing the use of many small cards that are harder to manage.

Reliability, Diagnostics, and OEE

Shoplogix notes that I/O modules contribute to automation reliability by supporting error detection, data buffering, and transaction management. Asteam Techno similarly emphasizes improved diagnostics in the 1762-OB32T, including current feedback and fault detection that “keep systems healthy.” These features are not nice-to-haves in a large application; they are essential to sustaining high overall equipment effectiveness.

In practice, diagnostic capability means you can detect field shorts, broken wires, and overloaded channels without guessing. With current feedback and per-group or per-point fault flags, your PLC logic can raise targeted alarms, guide technicians to the right terminal block, and even implement basic redundancy or fallback behavior in response to detected faults.

From a systems perspective, this diagnostic data becomes part of the plant’s analytics and reliability program. Trends in output module faults can reveal underlying issues such as poor cable routing, insufficient surge protection, or load devices being driven too close to their ratings. When you multiply that insight across hundreds or thousands of outputs, the impact on uptime is substantial, as illustrated by the beverage plant that cut downtime by roughly forty percent after deploying transistor modules with better diagnostic behavior.

Treating the Specification as a Design Output

In regulated industries, Aztechnica’s overview of design outputs and design verification and validation frames design outputs as the documented results of design activities that define the product and its manufacturing process. While that article focuses on medical devices and cites frameworks such as FDA 21 CFR 820.30 and ISO 13485, the underlying principles apply directly to industrial control hardware.

For a 32-point output module in a large system, the specification should be written as a design output that is specific, measurable, and testable. That means clearly defined requirements such as output voltage ranges, per-channel current limits, backplane current draw, isolation ratings, environmental operating ranges, and allowed load types. Each of these should be traceable back to design inputs such as plant power distribution standards, safety requirements, and environmental conditions.

Design verification then becomes the process of proving that the chosen module and configuration meet those requirements. That may include bench tests to confirm that channels can drive representative loads within the stated current limits, inspections to ensure backplane loading stays within the controller’s rating, and analyses to confirm thermal behavior in worst-case cabinet conditions.

Design validation, in the Aztechnica sense, is about demonstrating that the overall control system, as built, meets user needs in real or simulated operation. For a 32-point module, this includes confirming that the mix of loads it drives performs as the process requires, that diagnostic information is surfaced appropriately to operators and maintenance, and that faults in field devices or wiring are handled safely.

Risk management should be integrated throughout. If a channel sticks on or off, what is the hazard? If a group loses power, what equipment states result? By treating the module specification and its integration plan as formal design outputs, and by planning verification and validation activities early, you avoid last-minute design changes that are disruptive and expensive at plant scale.

Power, Thermal, and EMC Considerations Around the Module

Although a 32-point output card is not a power converter in the Vicor or Monolithic Power sense, it sits at the intersection of logic and power and is subject to many of the same design realities. Monolithic Power Systems stresses efficiency, thermal management, and electromagnetic compatibility as pillars of good power circuit design. Those themes carry over almost unchanged.

On the power side, each output channel introduces conduction losses proportional to the current and the effective resistance of the switching path. When many points switch simultaneously, the aggregate heat is not trivial. Derating, both at the load level and at the module group level, is one of the most effective tools you have. Monolithic Power notes that running components at a fraction of their maximum ratings, such as around seventy percent of rated current, can significantly extend life and reduce stress.

Thermal management in a dense PLC panel involves more than checking a catalog temperature range. You need to consider cabinet layout, airflow, the proximity of heat-generating devices such as drives or power supplies, and the possible use of heat sinks or forced-air cooling in particularly dense areas. Effective thermal design ensures that the module’s operating range, such as the 32 to 131 °F rating for the 1762-OB32T, is not exceeded in real life when several panels stand side by side in a hot utility room.

EMC and noise are also material concerns. Monolithic Power highlights the importance of filters, decoupling capacitors, and careful layout to control conducted and radiated noise in power circuits. Digital output modules that switch dozens of loads, especially inductive devices like solenoids and small motors, can create significant transients. Good practice includes proper suppression at the load, appropriate wiring practices, and thoughtful grounding. Vicor’s recommendation to keep low-level signal grounds separate from high-current power grounds and connect them at a single point is just as applicable inside a control panel as it is on a DC-DC converter board.

Taken together, these measures help ensure that the module does not inject excessive noise into sensitive analog circuits or communications networks, and that it remains robust against the electrical noise generated by the very loads it controls.

Modular Thinking Beyond Hardware

A surprising amount of insight comes from looking at how other fields treat modules. Software engineering articles from sources like PixelFreeStudio and vFunction emphasize principles such as single responsibility, high cohesion, low coupling, and clear interfaces. Terraform and Anaplan best practice guides similarly argue for small, opinionated modules that do one thing well, follow consistent naming, and minimize hidden dependencies.

You can apply exactly the same thinking to hardware I/O design. A 32-point output module that mixes unrelated voltage levels, safety integrity roles, and load types is the hardware equivalent of a “god object” in software. It becomes hard to reason about, hard to test, and hard to change. By contrast, grouping outputs so that each module serves a coherent purpose, such as all low-voltage valve manifolds for a particular skid, keeps cohesion high and coupling low. Documentation, troubleshooting, and future modifications all become easier.

Similarly, treating your output modules as reusable building blocks rather than one-off designs encourages better standards. Clear naming conventions for channels, consistent wiring practices, and standard diagnostic behaviors are the hardware counterpart of well-documented interfaces and versioned software modules. As Anaplan’s D.I.S.C.O. methodology suggests for model building, the goal is a logical, principle-driven structure rather than ad hoc accumulation of points wherever there is space.

Short FAQ on 32-Point Output Modules

Q: What kinds of devices are appropriate for a 32-point transistor output module such as the 1762-OB32T?

A: Asteam Techno notes that this kind of module is used to drive DC-powered devices like motors, warning lights, solenoid valves, and relays that are compatible with its 10 to 24 V sourcing outputs and 0.5 A per-channel rating. In large systems, that typically includes conveyor drives controlled through pilot relays, valve manifolds, indicator lights, and other discrete on and off loads that fall comfortably within that current envelope.

Q: How does a 32-point module improve panel and system design compared to lower-density cards?

A: The Asteam Techno analysis points to space-saving benefits, fewer modules per system, and better thermal behavior through group-based switching. In a large installation, this translates to fewer racks and cabinets, shorter wiring runs, and a clearer mapping between I/O cards and process zones. The reduced mechanical wear of transistor outputs compared to relays further improves uptime, as seen in the beverage plant case where downtime dropped by about forty percent and throughput rose by roughly twenty-three percent after migrating to transistor modules.

Q: What should I verify before standardizing on a specific 32-point output module for a large project?

A: Drawing on design output and verification concepts described by Aztechnica, you should confirm that the module’s numerical specifications match your design inputs: voltage and current ratings versus load requirements, backplane current draw versus controller limits, isolation and environmental ratings versus site conditions, and diagnostic behaviors versus your maintenance practices. Each of these items should be documented, linked to a verification activity such as a test or analysis, and integrated into your risk management and commissioning plans.

Closing Perspective

A 32-point output module may look like a small part on a bill of materials, but in a large control system it is a critical design output that touches power, safety, reliability, and maintainability. When you treat its specification with the same rigor you apply to your process and safety requirements, drawing on proven practices from Rockwell Automation case studies, Shoplogix I/O guidance, and power design principles from companies like Monolithic Power and Vicor, you end up with an architecture that scales cleanly instead of fighting you at every expansion. That is the kind of control system you can deploy, grow, and support over years without surprises, and it starts with specifying that 32-point module the right way.

References

- https://www.plctalk.net/forums/threads/allen-bradley-output-module-spike.30466/

- https://www.asteamtechno.com/1762-ob32t-output-module/?srsltid=AfmBOoraEwr8vHuGySpePJjXBjUhLw5X6ChJrKPPvvyeZRGja4uU5vY6

- https://blog.pixelfreestudio.com/best-practices-for-modular-code-design/

- https://shoplogix.com/inout-output-modules-explained/

- https://community.anaplan.com/discussion/35993/oeg-best-practice-best-practices-for-module-design

- https://aztechnica.com/resources/f/design-and-development-considerations-for-design-outputs-and-vv

- https://www.digikey.com/en/articles/optimizing-optical-module-performance-through-temperature-control

- https://www.johnsoncontrols.com/building-automation-and-controls/building-automation-systems-bas/input-output-modules

- https://www.linkedin.com/advice/3/what-best-practices-designing-control-system-edwgf

- https://plcdesign.xyz/en/selection-io-modules-design-phases/

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment