-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Quality Standards for Aftermarket Industrial Controls: A Systems Integrator’s Guide

When you live in the world of brownfield plants and retrofit projects, you quickly learn that “aftermarket” industrial controls can either quietly keep a facility running for another decade or drag it into a cycle of nuisance trips, cyber risk, and unplanned outages. The difference is rarely about brand alone. It is about whether those parts and the teams behind them are grounded in solid quality standards.

In this article I will look at aftermarket industrial controls through the lens of a veteran systems integrator and long-term project partner. I will draw on guidance from organizations such as ASQ, NIST, CISA, ISA, and OSHA, as well as lessons from automotive aftermarket certifications and control-system reliability studies, and translate them into practical decisions you can make on your next panel build, retrofit, or field replacement.

Why Aftermarket Controls Live or Die by Quality Standards

Industrial control systems are not ordinary IT assets. NIST’s guidance on industrial control system security emphasizes that for these systems the priorities are safety and availability, with integrity close behind and confidentiality trailing. That hierarchy reflects reality in the field. A failed PLC output, a mis-wired replacement safety relay, or a compromised remote-access path can injure people, damage equipment, and contaminate the environment.

Reliability and maintenance experts point out that control systems in process and discrete plants are expected to run around the clock with downtime limited to turnarounds. Under OSHA 1910.119, instrumentation and control components fall under the Mechanical Integrity element for covered processes. Regulations demand written maintenance procedures, inspection and testing with records, timely correction of deficiencies, and quality assurance for new construction and spare parts.

At the same time, the hardware lifecycle is fundamentally mismatched to that of the machines it controls. Case histories from machine builders show equipment designed for 20–30 years of service still running with control electronics whose typical lifespans are 7–12 years and with PC-based interfaces that may only be supportable for three to five years. Some operators stretch that gap by scavenging obsolete parts online, but as one integrator noted, “keeping legacy equipment running without replacing the hardware or software is a nice dream until something fails and you’ve used your last spare.”

In this environment, aftermarket controls are not a side show. They are the front line of mechanical integrity, safety, and cybersecurity. Quality standards are how you make sure those parts, and the organizations behind them, are fit for that purpose.

What “Quality Standards” Actually Mean in Industrial Controls

ASQ defines quality standards as documents that provide requirements, specifications, guidelines, or characteristics that can be used consistently to ensure that materials, products, processes, and services are fit for their purpose. Standards provide a shared vocabulary and objective benchmarks so that buyers, suppliers, integrators, and regulators can communicate clearly and verify performance.

In the context of aftermarket industrial controls, it helps to group standards into three overlapping categories. First are quality management system standards, such as ISO 9001, that govern how a supplier runs its business, controls processes, and improves over time. Second are technical and safety standards that define how control components and panels must be designed, built, and installed, such as NFPA 79 for electrical safety of machinery or UL 508A for control panels. Third are functional safety and cybersecurity standards that define how control systems must behave in the face of failures and threats, such as ISA/IEC 61511 for safety instrumented systems and ISA/IEC 62443 or NIST 800-82 for industrial control system security.

Use of many standards is formally voluntary, but various stakeholders often make them conditions of doing business. Regulators reference them as recognized good engineering practice. Large asset owners bake them into their specifications. Insurance companies and auditors look for them during reviews. If you are picking an aftermarket control component solely on the basis of price and a matching part number and ignoring these standards, you are accepting risk that is hard to quantify and even harder to justify after an incident.

The Standards Landscape That Touches Aftermarket Controls

The standards universe can be overwhelming, so it is useful to see how a few key documents map to aftermarket control decisions.

| Standard or framework | What it governs | Why it matters for aftermarket controls |

|---|---|---|

| ISO 9001 | Quality management systems | Shows that a supplier uses formal quality control, complaint handling, and continual improvement rather than ad hoc practices. |

| ISO/TS 16949 (IATF 16949) | Automotive-specific QMS | In the automotive supply chain, this signals tight control of defects and variation; the same discipline is relevant when an industrial control supplier also serves automotive customers. |

| NFPA 79 | Electrical safety of industrial machinery | Impacts wiring methods, protective devices, and safety circuits for panels and retrofits. Aftermarket components must support compliance. |

| UL 508A | Industrial control panel construction | Defines how listed control panels are designed and built; replacement devices must be suitable for use in UL 508A panels. |

| IEC 61131-3 | PLC programming languages and structures | Promotes maintainable PLC code; important when aftermarket controllers are introduced into existing architectures. |

| ISA/IEC 61511 | Safety instrumented systems in the process sector | Governs design, maintenance, and proof testing of safety instrumented functions; replacement sensors, logic solvers, and final elements must not degrade SIL or testability. |

| IEC 61508 | Functional safety of programmable electronic systems | Foundation for sector-specific safety standards; relevant when aftermarket devices are used in safety-related applications. |

| ISA/IEC 62443 | Industrial automation and control system cybersecurity | Provides a framework for secure design and maintenance of ICS; aftermarket hardware and firmware must support required security capabilities. |

| NIST SP 800-82 and CISA ICS guidance | ICS cybersecurity and risk management | Emphasize segmentation, secure remote access, and change control; influence how replacement devices are selected and deployed in OT networks. |

| OSHA 1910.119 MI | Mechanical Integrity for covered processes | Requires documented maintenance and quality assurance for new parts and systems. |

| SAE standards | Automotive component performance and interfaces | In the automotive aftermarket, these standards ensure compatibility and durability; they illustrate how detailed performance standards can stabilize complex supply chains. |

This matrix is not exhaustive, but it illustrates how quality standards are not abstract paperwork. They set expectations for how replacement parts are designed, manufactured, documented, and supported over their service life.

Lessons from the Automotive Aftermarket

The automotive aftermarket has already traveled much of the road industrial controls are on today. Vehicles on U.S. roads average about 12.5 years in age and around 13,500 miles per year, which means owners depend on replacement parts for hundreds of thousands of miles of service. According to automotive aftermarket analyses, certifications and standards are how that ecosystem maintains trust.

ISO 9001 is widely used to structure quality management at aftermarket suppliers. It tightens quality control, formalizes complaint handling, reduces waste, and mandates regular audits. ISO/TS 16949, developed by automotive and standards bodies, adds automotive-specific requirements focused on continual improvement, defect prevention, and minimizing variation across the supply chain. Leading automakers often require this certification from their suppliers.

On the product side, organizations such as the Certified Automotive Parts Association test and certify collision replacement parts to ensure they meet or exceed original equipment specifications. Independent bodies like NSF International also certify aftermarket components through quality and performance testing. European regulations require the E‑Mark for many parts sold in the European Economic Area, confirming compliance with safety and environmental directives and enabling market access.

Standards from SAE International define detailed performance, material, and dimensional requirements for components, which makes it possible to mix brands while still meeting performance expectations. The result is an aftermarket where third-party parts can be trusted, when certified, to perform on par with or better than original components.

Industrial controls do not yet have the same breadth of visible consumer-facing marks, but the principle is identical. QMS certifications, product safety standards such as UL 508A and NFPA 79, functional safety frameworks, and cybersecurity standards collectively play the role that CAPA, E‑Mark, and SAE play in automotive. If a supplier treats these as central to its business, its aftermarket controls are far more likely to support safe, reliable long-term operation.

Applying Standards When Selecting Aftermarket Industrial Controls

From a project and maintenance perspective, the standards only matter if they influence the parts you actually buy and how you deploy them. In practice I look at four dimensions when I evaluate aftermarket controls: risk, standards alignment, reliability and lifecycle, and maintainability including cybersecurity.

Start with Function and Risk, Not Just Part Numbers

Reliability-centered maintenance guidance, formalized in standards such as SAE JA1011 and JA1012 and applied in instrumentation studies, starts by asking what a device does, how it can fail, and what happens when it fails. It distinguishes evident failures that are immediately obvious and have direct consequences, from hidden failures that lurk until called upon, especially in protective layers such as safety instrumented systems.

Under OSHA’s mechanical integrity requirements and ANSI/ISA 61511, safety instrumented functions must have defined operations, maintenance, test intervals, and replacement rules. When you replace a sensor, final element, or logic solver in a safety loop, you are making a functional safety decision, not just a purchasing one.

The practical implication is that you should rank instruments and control components by the safety, environmental, and commercial consequences of their failure. A local display-only temperature gauge that has no interlocks attached can be purchased with relatively modest documentation, provided basic standards are met. A level transmitter that closes a safety critical valve, on the other hand, must be assessed for its role in the safety requirements specification, its proof-test strategy, and its compliance with relevant functional safety standards long before you look at the price.

Verify Standards Alignment on the Data Sheet and in the QMS

ASQ emphasizes that standards provide an objective basis for communication and expectations. For aftermarket controls that begins with the supplier’s quality management system. ISO 9001 certification is not a guarantee of perfection, but it does show that the company has documented processes, internal audits, corrective actions, and a commitment to continual improvement. In the automotive supply chain, ISO/TS 16949 goes further by explicitly targeting defect prevention and the reduction of variation and waste. The discipline behind that kind of QMS transfers well to industrial vendors who supply safety or production-critical control components.

On the technical side, you should look for explicit references to standards relevant to the product type and application. For a custom PLC-based system, RL Consulting highlights IEC 61131-3, which defines PLC programming languages and structures in a way that makes code easier to read, maintain, and upgrade. NFPA 79 sets requirements for wiring practices and control circuits in machinery, while UL 508A governs control panel construction. ISA/IEC 62443 provides cybersecurity guidance for industrial automation systems, and IEEE guidance addresses grounding and power quality. A vendor that does not know how its products fit into this picture is effectively asking you to shoulder the engineering risk.

Reliability-focused guidance on selecting component replacements suggests going beyond basic ratings and ensuring that operating stresses are substantially below the maximum ratings listed in the data sheet. Derating components, for example by operating them at a fraction of their voltage, current, power, or temperature limits, is a common reliability engineering practice and is reflected in reliability prediction methods such as failures-in-time rates and handbooks used in many industries. When you select replacements with higher ratings and better environmental margins, you reduce the likelihood of overstress failures in the field.

Supplier quality and screening also matter. Guidance on reliability stresses the value of parts from manufacturers with proven process control, appropriate screening or burn-in where justified, and clear documentation of qualification tests and quality levels. Without that, you may meet a design standard on paper while still inheriting field failure modes that are invisible during factory acceptance testing.

Look Past “Drop-in Replacement” to Reliability and Obsolescence

Legacy control system case studies show that full replacement, repair-only, and selective upgrade are three different strategies with very different risk profiles. Full replacement offers a clean slate but comes with high cost and substantial downtime. Repair-only strategies that depend on shelves full of obsolete spares can be cheap in the short term but become unsustainable as parts disappear, and they often mask deeper production and quality issues. Selective upgrades that target critical hardware while retaining still-supportable equipment can provide a strong middle ground when they are engineered carefully.

Machine builders describe supporting three-decade-old machines whose original PLCs and HMIs run on discontinued platforms. Supporting those systems can require reading program backups from five-and-a-quarter inch floppy disks and maintaining obsolete hardware solely for the sake of compatibility. The design life of heavy machinery, often 20–30 years, is out of sync with electrical components that may be officially supported for only 7–12 years and with PC-based devices that may see operating systems change every three to five years.

One case study of a medical device manufacturer illustrated the opportunity cost of clinging to legacy control hardware. Ten machines were consuming three maintenance technicians per shift to keep them running, yet throughput remained low and scrap high. Analysis showed that the root cause was not mechanical but tied to motion hardware and software that did not properly control continuous motion. By upgrading the controller and motion system, the integrator was able to program better motion profiles, greatly reduce jams and breakage, triple throughput, and significantly reduce scrap. The control upgrade paid for itself quickly.

The lesson for aftermarket controls is that “form, fit, function” is not enough. You should ask whether the replacement improves or degrades long-term reliability and whether it extends or shortens the obsolescence horizon. A part that technically drops into the same slot but ties you to unsupported firmware, obsolete operating systems, or fragile communication drivers is not a quality upgrade.

Ensure Maintainability, Documentation, and Testability

Reliable control systems are not just the result of good hardware; they depend on disciplined maintenance and documentation. Guidance on custom PLC maintenance emphasizes proactive inspections, verification of wiring and grounding, environmental management for panels, and regular testing of safety functions and alarms. It also stresses software housekeeping: reviewing and updating PLC programs for accuracy and efficiency, backing up software and maintaining version control, and keeping documentation synchronized with as-built implementations.

Recommended maintenance scheduling combines periodic tasks, such as quarterly inspections and annual detailed reviews in heavy-duty environments, with event-based checks after production changes, power incidents, or firmware updates. These practices are anchored in standards like NFPA 79 for electrical safety and supported by cybersecurity frameworks such as ISA/IEC 62443.

For aftermarket controls this means that any replacement component should come with clear documentation, including wiring diagrams, configuration parameters, programming examples where relevant, and change notes for firmware or hardware revisions. It should fit into your existing backup and recovery routines. Many reliability analyses highlight the importance of structured backup management for PLC programs, configurations, and data, with off-panel or offline storage and tested restore procedures. Aftermarket devices that require opaque proprietary tools, undocumented configuration steps, or fragile licensing mechanisms make that much harder and compromise maintainability.

Integrate Cybersecurity Requirements into Every Replacement

Industrial control cybersecurity guidance from NIST, CISA, and sector frameworks such as ISA/IEC 62443 and NERC CIP all stress that control systems must be designed and operated differently from IT systems. They highlight the need for asset inventories, segmented network architectures separating business and control networks, security zones for critical assets, demilitarized zones for information exchange, and tightly controlled remote access.

They also caution that patch and vulnerability management in OT must respect safety and uptime constraints. Patches and configuration changes need to be tested in representative environments, scheduled during maintenance windows, and accompanied by compensating controls when they cannot be applied promptly. Monitoring and logging must be tuned to ICS protocols and behaviors, and incident response must include safe-state procedures and recovery from trusted backups.

Aftermarket control components increasingly participate directly in this landscape. A networked drive, smart I/O rack, or remote HMI is no longer just a point device; it is a cyber-physical asset. When you select and deploy aftermarket devices, you should confirm that they support basic security capabilities such as authenticated access, role-based permissions, secure remote connections, and logging. You also need assurance that the vendor has a process to deliver security patches and documented methods to apply them without breaking functionality.

If a replacement device refuses to play in a segmented, monitored, change-controlled environment, or requires permanent vendor tunnels into your OT network, it is out of step with current ICS security best practices and should be treated as a risk. Quality in the modern aftermarket is inseparable from cybersecurity posture.

OEM versus Aftermarket: Pros and Cons through a Standards Lens

In many organizations there is a reflexive preference either for original equipment manufacturer parts at any cost or for the cheapest available aftermarket alternative. A standards-based view helps you see beyond that binary.

| Dimension | OEM-only mindset | Standards-led aftermarket approach |

|---|---|---|

| Technical compatibility | High, but can mask aging architectures and compatibility issues between old and new OEM products. | Requires more upfront engineering, but can introduce modern, standards-compliant components that integrate cleanly into the broader control architecture. |

| Cost and availability | Often higher cost and longer lead times, especially for legacy platforms; may involve sole-source dependence. | Can reduce cost and shorten lead times if components adhere to relevant standards and quality certifications. |

| Reliability and lifecycle | Strong initial performance, but long-term support may end abruptly as product lines are discontinued. | With careful selection, can improve reliability (through better ratings and modern design) and extend lifecycle, provided vendors commit to long-term support. |

| Safety and compliance | Easier to assume compliance, but requires verification as standards and interpretations evolve. | Must be explicitly checked against standards, but can deliver equal or better compliance if suppliers build to NFPA, UL, functional safety, and cybersecurity frameworks. |

| Cybersecurity and diagnostics | Older OEM gear may lack modern security or diagnostic features, and upgrades may require full platform migrations. | Modern aftermarket devices can provide improved security, diagnostics, and data visibility if designed to ICS security and data standards. |

The conclusion is not that aftermarket is always better than OEM, or vice versa. The point is that when you put quality standards at the center of your decision, you get a clearer picture of the tradeoffs and avoid surprises.

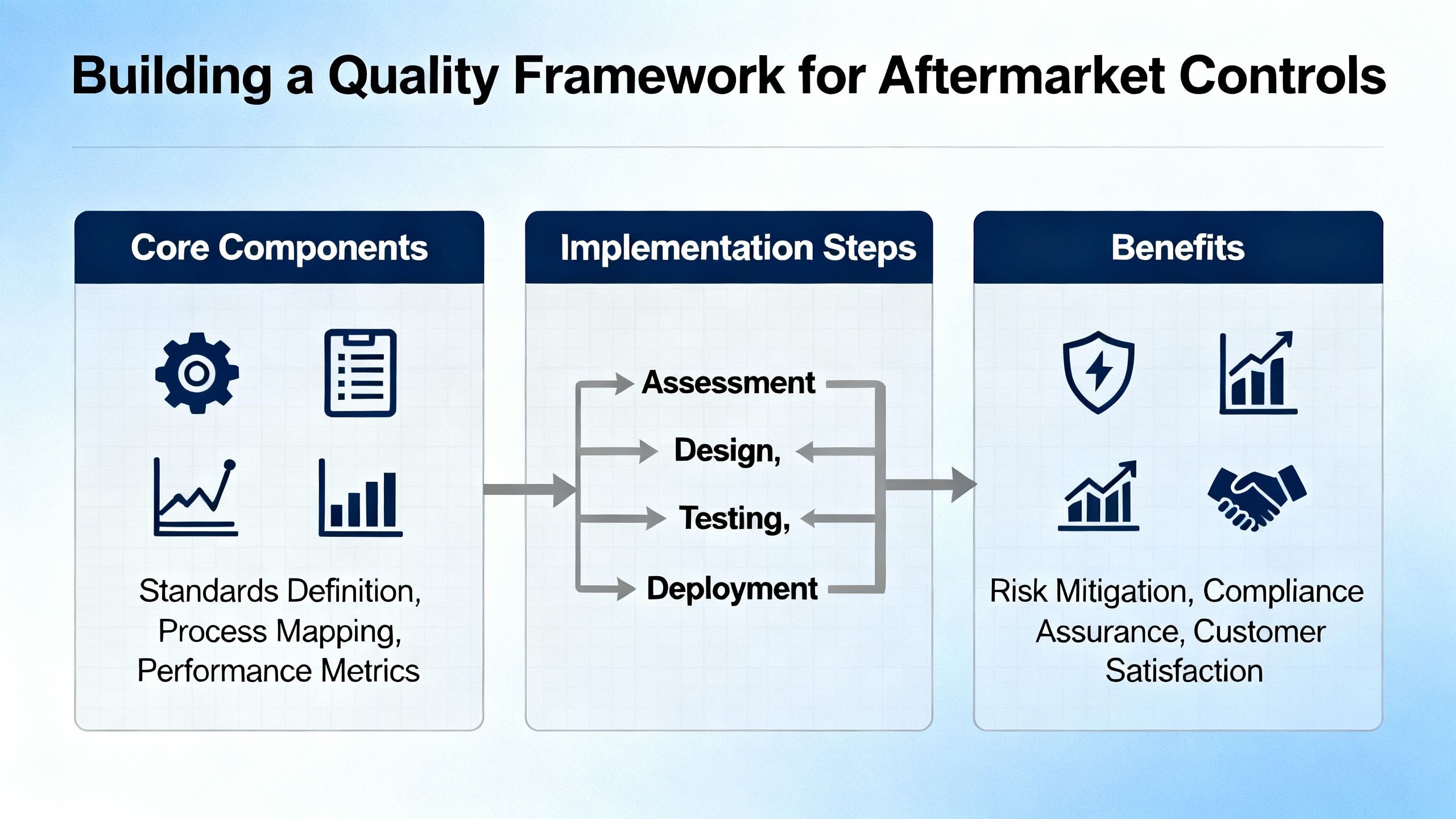

Building a Quality Framework Around Aftermarket Controls

Selecting a better relay or PLC module is useful, but the real gains come when you embed standards and quality thinking into your broader processes. That means integrating quality control, quality assurance, and risk management into the way you specify, purchase, install, and maintain aftermarket controls.

For Plant Owners and Maintenance Leaders

Industrial quality control frameworks describe QC as the set of procedures and tools that detect defects during production and QA as the process-oriented layer that prevents defects by designing robust systems. In manufacturing, these frameworks involve defined specifications, documented procedures, sampling and inspection, Statistical Process Control, and structured corrective and preventive action.

You can apply the same logic to aftermarket controls. Begin by making your expectations explicit. Recognize customer and regulatory requirements for safety, reliability, and uptime, and translate them into standards-based specifications for control hardware and software. Develop a quality manual that describes how control components are evaluated, qualified, and tracked. Create procedure manuals that explain how technicians install, test, and document replacements.

Track quality-related costs associated with control-system issues separately from general maintenance. That includes unplanned downtime due to control failures, rework or scrap attributed to control misbehavior, and emergency callouts for troubleshooting. Quality management practitioners note that these costs can be high but often remain invisible even in companies that care deeply about quality. Once you can see them, you can justify investments in better components, training, and processes.

Use data to guide decisions. Manufacturing quality guidance recommends monitoring critical metrics and using tools such as Pareto charts, control charts, and root cause analysis methods like the 5 Whys and Failure Mode and Effects Analysis. You can apply those to recurring control faults and field failures: which devices fail most often, under what environmental conditions, on which lines, and with what consequences. That analysis should feed back into your approved parts list and vendor evaluations.

Finally, integrate control-system quality into your broader risk and cybersecurity programs. ICS security frameworks call for asset inventories, risk assessments, and continuous monitoring, all of which depend on knowing what equipment you have and how it behaves. Aftermarket controls that fit into this framework make governance easier; those that do not become liabilities.

For OEMs and Systems Integrators

If you design and deliver industrial control systems, your choices determine how easy and safe aftermarket support will be for the next fifteen or twenty years. Testimonials from practitioners of ISA standards emphasize that structured design frameworks such as ISA-88 for batch control and ISA-95 for enterprise-integration models make control systems easier to configure, maintain, and modify. They separate product recipes from equipment models, encourage modular control code, and reduce the need to touch base-layer logic when process tweaks occur.

Adhering to NFPA 79, UL 508A, IEC 61131-3, ISA/IEC 62443, and relevant functional safety standards from the beginning builds quality and compliance in. It means that when a field technician replaces a valve actuator, safety relay, or I/O card years later, they have clear documentation, consistent naming, and a known design philosophy to work within.

It also means thinking about lifecycle and obsolescence from the start. Designing networks and control architectures that can evolve, selecting platforms with clear support roadmaps, and avoiding unnecessary proprietary lock-in makes it easier to introduce high-quality aftermarket options when the original hardware ages out. OEMs and integrators that position themselves as long-term partners often maintain backups, archived programs, and spare hardware for their customers, and they engineer upgrades that preserve operator look and feel even as underlying technology is modernized.

For Aftermarket Component Manufacturers and Distributors

If you make or distribute aftermarket industrial control components, quality standards are your primary differentiator in a crowded market. Automotive aftermarket experience shows that investing in appropriate certifications and testing programs pays off in trust and access. ISO 9001 serves as a baseline QMS. Additional sector-specific certifications, such as those used in automotive and other regulated industries, demonstrate deeper alignment with customer expectations.

Beyond QMS, you can strengthen your position by aligning products with the technical standards your customers must live under, such as NFPA 79, UL 508A, IEC 61131-3, ISA/IEC 62443, and functional safety frameworks where appropriate. Provide clear, concise, and accurate product data and documentation. Analyses of product information management in the automotive space highlight that accurate, consistent data underpins compliance, customer confidence, and operational efficiency. The same is true for industrial control components.

Your testing, screening, and qualification methods should be transparent. If you use environmental testing, burn-in, or statistical sampling, explain how they align with reliability and safety expectations. If your devices are intended for use in critical safety or cybersecurity contexts, show how they support higher integrity levels or security capabilities. In a market where many low-cost alternatives compete on price alone, quality standards are how serious buyers tell the difference.

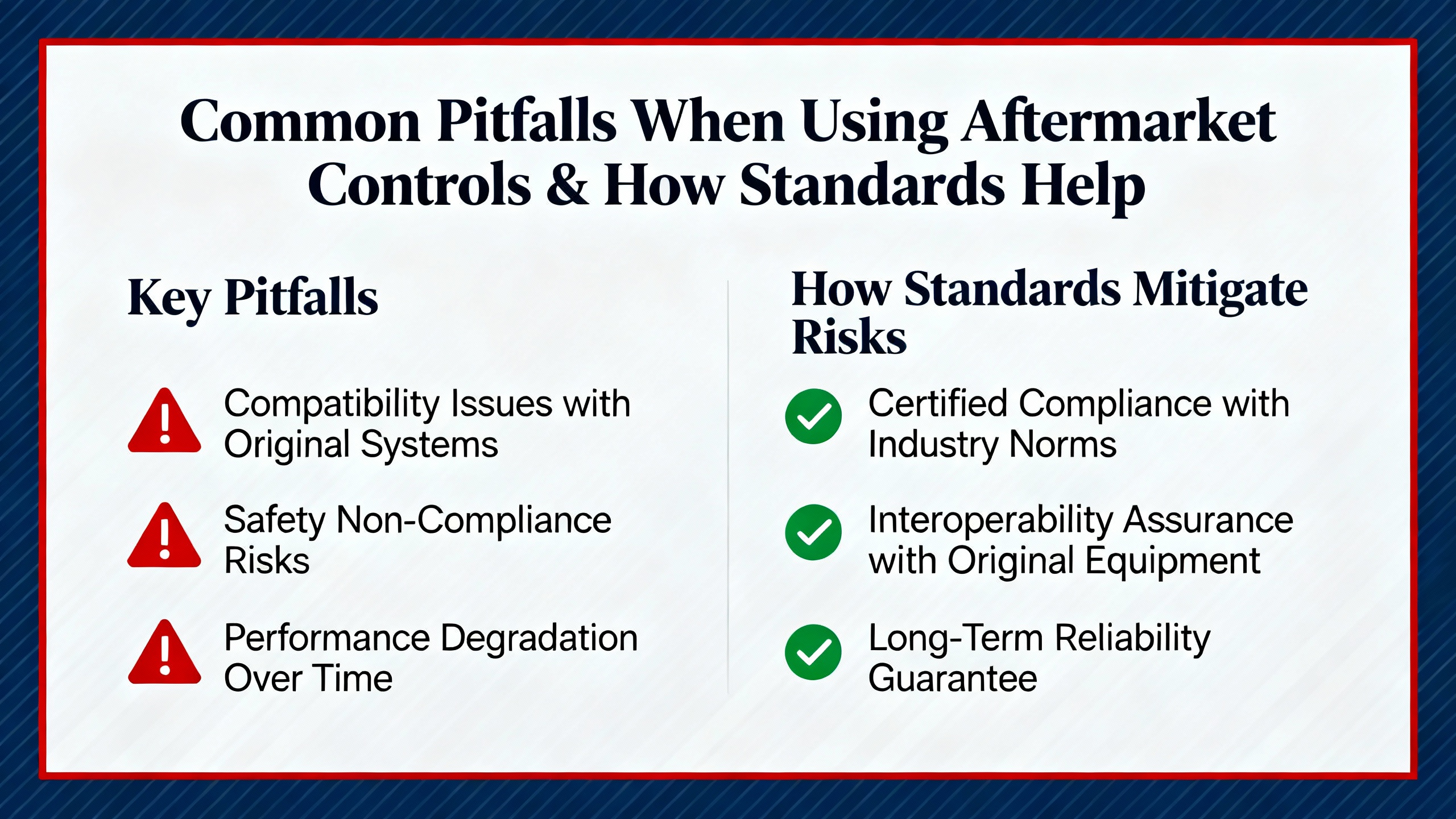

Common Pitfalls When Using Aftermarket Controls and How Standards Help

Several recurring problems show up when plants rely on aftermarket controls without a standards mindset. One common failure pattern is treating safety and non-safety circuits the same. Swapping a safety-critical sensor or relay with a general-purpose alternative because it is cheaper or available faster can erode the performance of safety instrumented functions and violate the assumptions behind functional safety analyses. Standards such as ISA/IEC 61511 exist precisely to prevent that kind of silent degradation.

Another pitfall is underestimating compatibility and lifecycle issues when mixing old and new technologies. Practical experience described by integrators shows that software and firmware incompatibilities between vintage PLCs and modern smart modules, drivers, and operating systems generate pop-up warnings, intermittent failures, and obscure bugs. These issues often surface only after partial upgrades, when “old software talks to new devices or new software talks to old devices.” Standards-based architectures and disciplined change control, as recommended by ISA, NIST, and CISA, reduce the number of such surprises and make it easier to isolate and resolve them when they arise.

A third trap is neglecting documentation and backups. When upgrades or replacements are done as “Band-Aid” fixes, with minimal documentation, it becomes difficult to troubleshoot and nearly impossible to roll back safely. PLC maintenance best practices and ICS security guidance both stress the importance of current as-built drawings, configuration records, and tested recovery procedures. In a crisis, the difference between a system with structured backups and one without often translates directly into hours or days of downtime.

Finally, there is the temptation to treat cybersecurity as separate from maintenance and quality. In reality, patching, access control, and configuration management are all quality processes. ICS cybersecurity best practices from organizations such as NIST, CISA, and ISA emphasize that vulnerabilities in aftermarket devices, unmanaged remote access paths, and unlogged changes to controller logic can have safety and reliability consequences just as real as a failed relay. Integrating cybersecurity requirements into your part selection and maintenance procedures is therefore part of quality, not an optional add-on.

FAQ: Practical Questions About Quality Standards and Aftermarket Controls

How do I verify that an aftermarket supplier actually follows the standards they claim?

Start by requesting certificates and audit summaries for their quality management system, such as ISO 9001, and any sector-specific certifications they cite. Ask for sample test reports or qualification summaries that reference the relevant technical standards, such as NFPA 79, UL 508A, or IEC 61131-3. Compare their documentation and support practices against guidance from organizations like ASQ and ISA: do they provide clear change histories, instructions, and support commitments, or just a catalog page? Persistent transparency is a better indicator of compliance than a logo on the box.

Can I safely mix OEM and aftermarket control components in the same panel or system?

Mixing components is possible and common, but it has to be done deliberately. The key is to make sure the combined system still complies with the safety, functional safety, and cybersecurity standards that apply to your facility. That means confirming electrical and environmental ratings, ensuring that safety instrumented functions retain their required performance, and validating that communication and security architectures remain robust. Guidance on batch and modular control design projects, such as ISA-88, shows that modular architectures are more forgiving of mixed equipment, but they still rely on disciplined engineering and documentation.

What is the most important standard to focus on if I am just starting to formalize quality for aftermarket controls?

The answer depends on your role. For a plant owner or maintainer, starting with ISO 9001 concepts inside your own organization and integrating OSHA mechanical integrity expectations into your maintenance program is often the highest-leverage move. That will naturally point you toward suppliers who share the same quality mindset. For a supplier, obtaining ISO 9001 and making sure your products explicitly support the technical and safety standards your customers must comply with, such as NFPA 79 and UL 508A for panels, is a realistic initial focus. Over time you can add functional safety and cybersecurity frameworks as your offerings expand.

How should cybersecurity standards influence my choice of aftermarket controls today?

Cybersecurity standards and best practices for industrial control systems emphasize asset inventories, segmentation, managed remote access, and disciplined patching and change control. When you choose aftermarket controls, that means favoring devices that can be hardened, monitored, and updated within that framework. Look for support of authenticated access, role-based permissions, secure protocols where appropriate, and vendor patch policies. Devices that only operate with hard-coded credentials, permanent vendor remote tunnels, or unpatchable firmware undermine your ability to comply with ICS security guidance and should be treated as higher risk.

A well-designed industrial control system is not defined by the logo on its components but by the standards and discipline behind them. When you let quality standards drive your aftermarket decisions, you stop gambling on short-term fixes and start building systems you can support with confidence for the long term.

References

- https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/specialpublications/nist.sp.800-82r2.pdf

- https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Cybersecurity_Best_Practices_for_Industrial_Control_Systems.pdf

- https://asq.org/quality-resources/learn-about-standards?srsltid=AfmBOorznZoZIcGLSFnCtBrVYPF0OX_UK_riaVz4Tji8QGYAx19Sp8hq

- https://www.isa.org/standards-and-publications/isa-standards

- https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202408.2000/v1/download

- https://citainsp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/ECS-RSP-Study-1a-reliability-ECS.pdf

- https://library.automationdirect.com/replace-legacy-control-systems-issue-30-2014/

- https://www.cates.com/control-panel-manufacturing-process-of-quality/

- https://www.cedengineering.com/userfiles/B01-002%20-%20Selecting%20Component%20Replacements%20to%20Improve%20Reliability%20-%20US.pdf

- https://www.csemag.com/know-whether-its-time-to-replace-a-control-system/

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment