-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Allen Bradley 1769-L33ER CompactLogix Availability: Stock Status and Lead Times

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

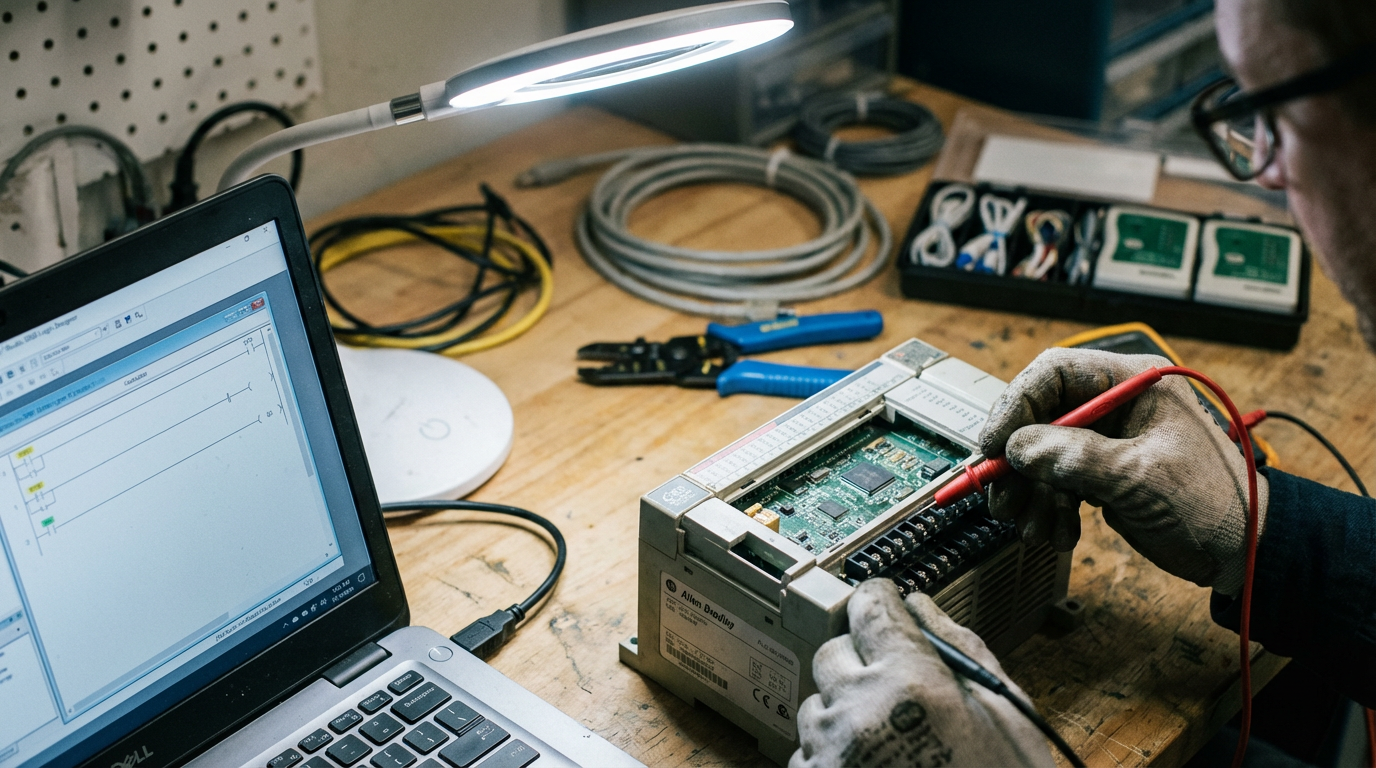

When a CompactLogix controller fails on a running line, the only lead time that matters is how long it takes you to get a replacement into the rack and back online. For many plants, the Allen Bradley 1769-L33ER CompactLogix 5370 L3 controller is the brain of a medium-sized system, and its availability has turned into a strategic risk, not just a line item on a parts list.

Looking across current product information and supply chain research, one theme is consistent: you cannot treat a CPU like the 1769-L33ER as just another catalog number. You need a clear view of where stock actually exists, how long it takes to get to your dock, and what you can do inside your own organization to keep that risk under control.

This article looks at availability and lead times for the 1769-L33ER from the perspective of a systems integrator who lives with the consequences on the plant floor. It combines documented details about the controller itself with broader lead-time and inventory best practices from supply chain research, and turns them into pragmatic guidance you can apply in your spare strategy and project planning.

Where The 1769-L33ER Fits In Your Architecture

The 1769-L33ER sits in the CompactLogix 5370 L3 family, designed for medium-sized automation tasks. According to product briefs from industrial distributors, it provides 2 MB of user memory, supports Compact 1769 I/O modules without a separate rack, and drives up to 16 local I/O modules with the option for multiple expansion banks. That combination is powerful enough for a packaging cell, a material handling zone, a batch skid, or a small assembly line, without the footprint or cost of a full ControlLogix chassis.

Networking is one of the reasons this controller is so widely used. Documentation from resellers describes dual embedded EtherNet/IP ports that form an internal switch, supporting standard 10/100 Mbps Ethernet and up to 32 Ethernet nodes. That gives you enough room for HMIs, SCADA, drives, gateways, and weight processors on the same network. Devices such as Hardy weigh scale modules for CompactLogix, for example, feed high-speed weight data directly over the backplane into controllers like the 1769-L33ER and then out over EtherNet/IP to the wider system.

Physically, the controller mounts on a DIN rail or panel with the 1769 I/O family and uses a 24 V DC supply and dedicated 1769 power modules. Typical datasheets highlight a compact open-style enclosure, modest power dissipation, and operating temperatures roughly in the 32–140 °F range, which makes it straightforward to deploy in standard MCCs and line panels. A USB port is provided for local programming and troubleshooting, while the main runtime communication rides on Ethernet.

Taken together, these traits explain why the L33ER has become a bottleneck component in many plants. It is modern enough to be deployed broadly, capable enough for a wide range of duties, and integrated deeply with plant networks and third-party hardware. When you cannot get one, entire areas of the plant are suddenly at risk.

Availability, Stock Status, And Lead Time: What They Really Mean

Before you can manage availability, you need to be precise about the terms you use internally. Supply chain research from manufacturing-focused sources such as MRPeasy, Atlassian, and StockIQ draws some useful distinctions.

Lead time is the total calendar time between a defined start and end point. In a simple e-commerce example, if you place an order on January 1 and receive the box on January 15, the lead time is 14 days. For a controller like the 1769-L33ER in an industrial context, the definition you choose matters more than the formula. You might define procurement lead time as the period from the date your purchasing team cuts a purchase order until the day the controller is received, inspected, and booked into inventory ready for issue.

Researchers emphasize that you must standardize those start and end points. Some organizations start the clock when the requisition is approved; others wait until the PO hits the supplier’s system. Some stop the clock when the box lands on the dock; others only when the item is visible in the inventory system and ready to ship to a plant. If you do not lock in that definition, your lead-time metrics will drift and become impossible to compare over time.

In manufacturing literature, several flavors of lead time are defined. Procurement lead time covers supplier ordering and shipping. Manufacturing lead time covers your own production from work-order release to finished goods. Customer lead time is what the end customer experiences from order confirmation to delivery. For a critical spare such as the 1769-L33ER, procurement lead time is the one that usually hurts you first, but customer lead time will matter if you are integrating these controllers into machines you ship.

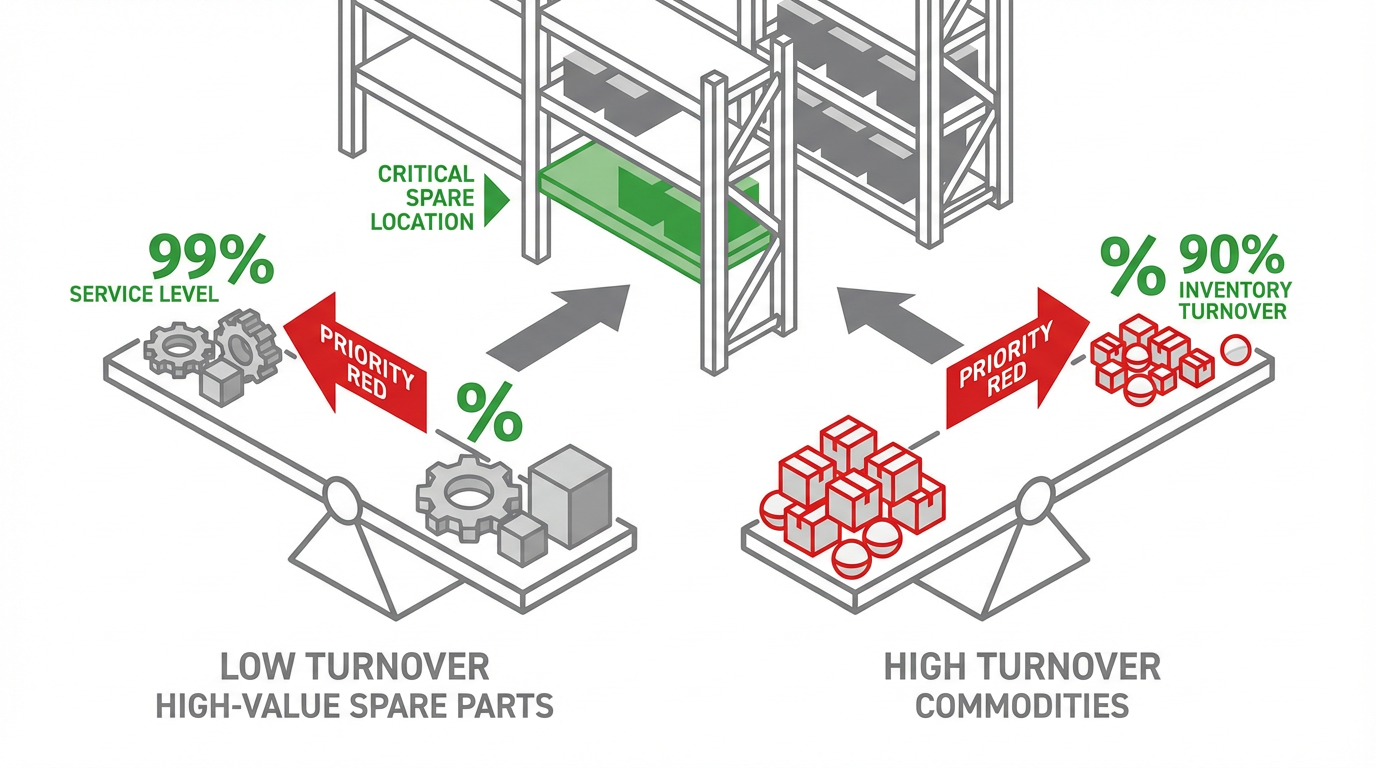

Availability and stock status are related but different concepts. Availability is normally expressed as a service level or fill rate: the percentage of requests you can cover immediately from stock. Research from ABC Supply Chain stresses that service level is one of the two fundamental inventory KPIs, alongside inventory turnover. Stock status is simply the current on-hand and on-order picture: how many units you physically hold, how many are reserved, and how many are on purchase orders with projected receipt dates.

The trap many organizations fall into is chasing perfect availability on every item. ABC Supply Chain points out that a genuine 100 percent service level implies infinite inventory and is economically unrealistic. The right approach is to deliberately set high service targets for a small number of critical SKUs and accept a lower service level on slow movers. For most plants, the 1769-L33ER sits firmly in that critical category.

Why Lead Times For Controllers Have Become So Uncertain

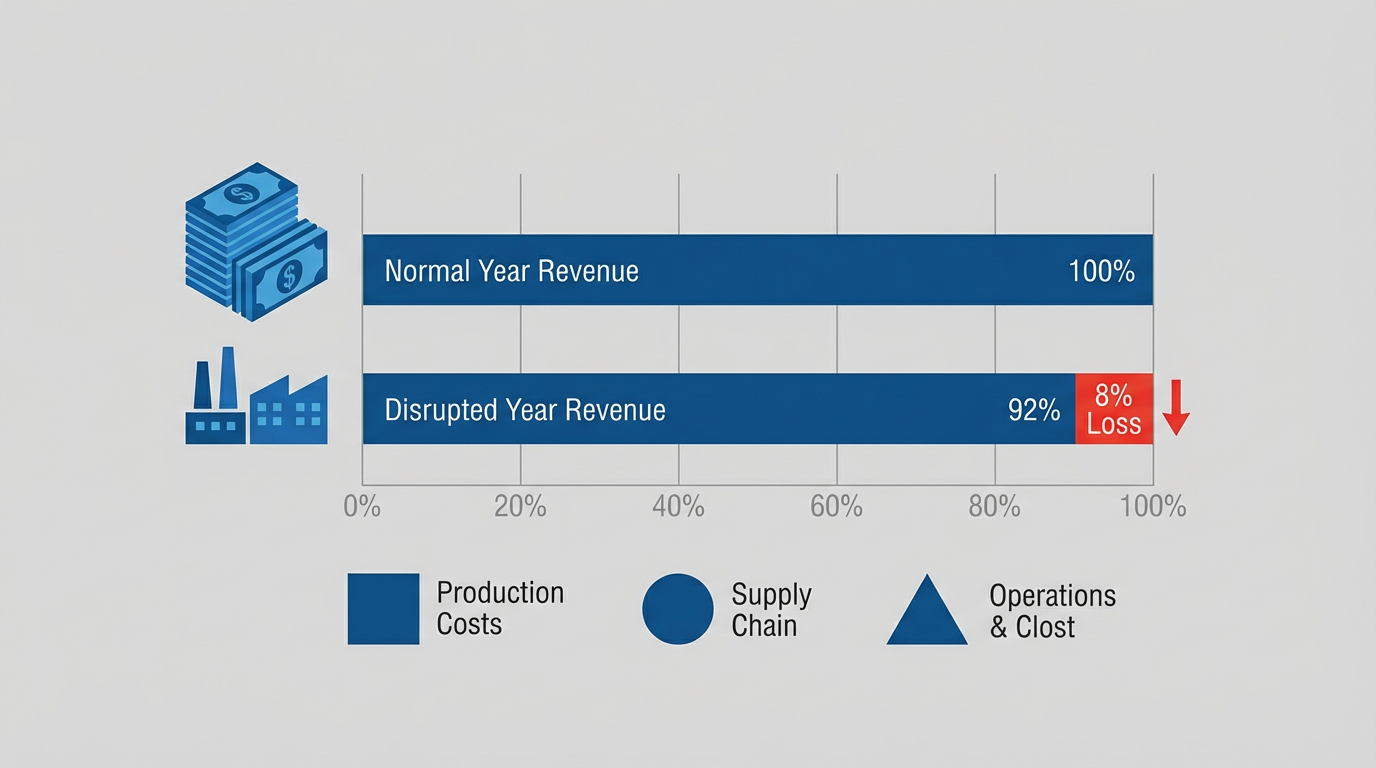

Current research on manufacturing supply chains shows that long and volatile lead times are no longer rare exceptions. A lead-time study cited by MRPeasy notes that average raw-material deliveries have stretched from about 65 days to 81 days, a roughly 25 percent increase. The same work highlights that supply disruptions now cost manufacturers on the order of 8 percent of annual revenue. That is not a rounding error; it is the difference between a solid year and a painful one.

Electronics are particularly affected. MRPeasy reports component lead times in the range of 12 to 40 weeks, with some common parts such as capacitors reaching about 34 weeks and automotive semiconductors running just under 13 weeks. A controller like the 1769-L33ER is built on exactly that kind of silicon. Even if Rockwell Automation and its contract manufacturers shield you from the raw component chaos, those pressures show up eventually in controller availability, especially when demand spikes.

Supply chain specialists such as RELEX Solutions and StockIQ emphasize that lead time is not just about transportation. Shipping a finished product across an ocean may be a fixed four-week segment, but the real variability lies upstream, in how long suppliers need to plan production, secure components, and sequence manufacturing. When demand surges for controllers, the delay is just as likely to be waiting for a production slot as it is waiting for a container ship.

Finally, the way you place orders affects your own experience of lead time. Research compiled by Plex (part of Rockwell Automation) and Intellichief shows that large, infrequent bulk orders magnify the impact of any disruption. Shorter, more frequent orders reduce inventory on hand but also expose weaknesses in forecasting and supplier performance. For a controller, where minimum order quantities are typically low but supply can be constrained, you need to balance those factors carefully.

What The Market Signals About 1769-L33ER Stock

While this article does not rely on real-time stock feeds, the research notes provide a snapshot of how widely the 1769-L33ER appears across the market.

Dedicated product pages from industrial suppliers describe the 1769-L33ER as a CompactLogix 5370 L3 Ethernet controller with 2 MB of user memory, a 1 GB Secure Digital card for program storage, and support for up to 16 expansion I/O modules. That kind of detail appears in listings from sites focused on automation hardware, which suggests they handle enough volume to justify maintaining technical content, not just a bare catalog number.

Resellers such as PLCCable describe specific shipping options for this controller. Their listing outlines domestic shipping methods like USPS First Class at roughly three to seven days, USPS Priority Mail at about two to three days, and UPS Ground ranging from around one to six business days. They also offer expedited services such as UPS Next Day Air and Second Day Air, ship orders Monday through Friday, and provide international express options with transit times in the one to fourteen day window once the unit leaves the warehouse. Those numbers represent transportation lead time only, but they show that for in-stock units, the physical move from their shelves to your dock is measured in days, not months.

Marketplaces add another layer. An eBay listing for a 1769-L33ER emphasizes fast shipping but also highlights the realities of international trade: customs inspections can cause delays, import duties and taxes fall on the buyer, and brokerage fees may be due at delivery. That aligns with broader research from StockIQ showing that customers are increasingly intolerant of vague or extended delivery windows and will abandon purchases when shipping times look excessive or unclear.

At the same time, some captured pages from distributors and hardware brokers are not product content at all, but human-verification or security-gate screens. When automated tools fetch a page and encounter a verification step instead of actual specifications, the result is a placeholder with no data on availability or lead time. The presence of these gates tells you that many retailers are actively defending their sites against bots and scraping, which means you should not trust archived snippets alone. For any serious project, you need to validate stock status directly with the supplier.

Finally, legal and firmware disclaimers from surplus specialists such as PDF Supply reveal another facet of the market. They state explicitly that they are not authorized Rockwell distributors, that firmware on a shipped module may not match your needs, and that it is the customer’s responsibility to secure proper firmware licenses and any required software from official sources. In practice, that means you might find a controller quickly through a surplus channel, but you still need to budget time for firmware alignment and licensing checks before dropping it into a running system.

Comparing Your Sourcing Options

Different channels behave differently once you look past the marketing. Based on the research notes, you can think about your options for 1769-L33ER procurement along these lines:

| Source type | Examples from research notes | Lead-time behavior once in stock | Key risks for a 1769-L33ER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authorized-style industrial e-commerce reseller | PLCCable listing for 1769-L33ER/A with stated shipping methods | Domestic shipping committed in ranges of roughly 1–7 business days depending on service level, with international express options around 1–14 days; assumes unit is on the shelf | Actual stock position may differ from what the website implies; you still need to confirm availability and manufacturing lead time for backordered items |

| Surplus and secondary market specialists | PDF Supply legal notices; Quick Time Engineering product page; Radwell catalog stub | Hardware may ship quickly if physically on hand, often within normal parcel-carrier timeframes similar to other resellers | Not authorized by the OEM; firmware revision and licensing are not guaranteed; you must validate compatibility with your Studio 5000 environment and internal standards |

| General marketplaces and auction platforms | eBay listing for a 1769-L33ER with international shipping information | Seller-dependent; transit time influenced heavily by customs processing, import duties, and brokerage; delays are explicitly called out as possible | Quality and provenance of hardware can vary; returns may be difficult; customs and tax treatment adds uncertainty to both lead time and total landed cost |

From a project and maintenance perspective, the takeaway is straightforward. In-stock units from reputable industrial resellers can typically reach your dock within a week inside the United States and within one to two weeks internationally, based on the shipping windows they publish. The dominant uncertainty is not parcel-transit time, but whether the unit is truly in stock and what the replenishment lead time will be if it is not.

Treating The 1769-L33ER As An A-Class Item

Inventory experts often use ABC analysis to avoid treating every SKU as equally important. Research from ABC Supply Chain shows that a small fraction of products usually drives the majority of value and risk, and that companies should focus their cash and attention on those A items. For most plants running CompactLogix systems, the 1769-L33ER is one of those A items, even if its annual usage volume is low.

The first step is to define the two basic KPIs recommended in that research: service level and inventory turnover. Service level for this controller is the probability that when maintenance needs a replacement, one is immediately available in your storeroom. Inventory turnover measures how many times per year you consume and replenish that stock.

If you carry one or two L33ER units across many years with no failures, your turnover will look terrible, but that does not mean your stocking strategy is wrong. For a CPU that can shut down an entire area when it fails, service level matters more than turnover.

The right conversation is whether you are willing to accept a stockout on that part at all, knowing that current electronics lead times often run into months.

At the same time, the ABC Supply Chain work on slow and obsolete stock is a useful warning. It recommends systematically identifying slow and obsolete stock and then taking deliberate actions such as canceling purchase orders, returning product, or liquidating excess. For controllers, that means periodically reviewing your spares and asking which catalog numbers still exist in the plant and which ones have been fully migrated out. You may decide to keep generous coverage on a controller like the 1769-L33ER while aggressively clearing out remnants of older, retired CPU families.

Minimum order quantity is another factor highlighted in that research. High MOQs can force you to buy years of demand in a single batch. For common controllers, MOQs are usually modest, but they can still create overstock if you have transitioned most lines to a newer platform and forgot to adjust your purchasing patterns. The recommendation from that research is to negotiate MOQs, explore alternative suppliers if necessary, and even consider removing a SKU from your approved list when MOQs make rational stocking difficult.

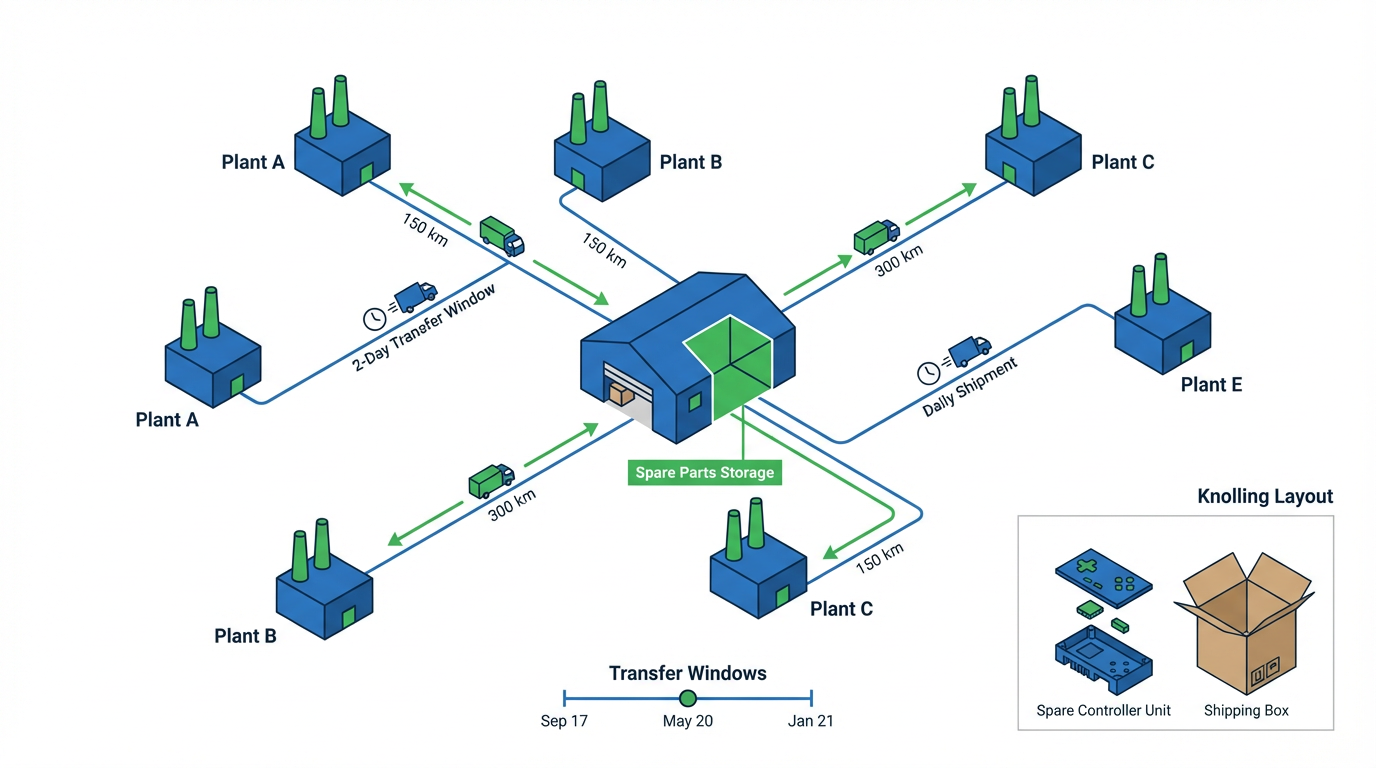

Centralizing inventory is also stressed. Holding a small pile of L33ER units in every plant ties up more capital than pooling them in a regional or corporate store and having a clear transfer process. The research notes that centralization tends to lower total stock and simplify management by aggregating demand, even though it may slightly increase outbound transport distances. For a high-value controller, that trade often makes sense, provided your internal logistics can deliver a spare to a plant within an acceptable time window.

Reducing Lead Time For 1769-L33ER Orders

You cannot control Rockwell’s production schedule, but you can control how you interact with your suppliers and how efficiently you process what you buy. Several strands of supply chain research point to practical levers that matter even for a single part like the 1769-L33ER.

Map And Measure Your Real Lead Time

Guides from Atlassian and MRPeasy stress that you must define precisely where lead time starts and ends. In practice, that means agreeing whether the clock starts when engineering requests a controller, when purchasing places the PO, or when the supplier acknowledges it, and whether it stops when the controller lands at your central warehouse or when it is booked into your maintenance store.

Once the definition is fixed, you should measure lead time for this controller separately by supplier. MRPeasy recommends using order-level timestamp data over several months and computing average lead times as well as the variation around those averages. It also suggests using weighted averages so that an occasional large order does not distort your understanding.

For a controller that can halt production, variation matters as much as the average. If one supplier consistently quotes and delivers in similar windows while another swings wildly depending on global conditions, your stocking and sourcing strategy should reflect that difference.

Strengthen Supplier Relationships Around This Specific Part

Multiple sources, including StockIQ, Intellichief, and RELEX Solutions, converge on one message: lead time management is an ongoing collaboration problem, not just a price negotiation.

StockIQ notes that modern supply chains run better when suppliers see accurate forecasts and inventory positions rather than sporadic rush orders. MRPeasy and Intellichief highlight that sharing realistic forecasts allows suppliers to pre-position inventory, reserve capacity, and plan logistics, which shortens effective lead time and reduces surprises. RELEX adds that better collaboration is particularly powerful for long-lead-time products, provided you give suppliers enough visibility.

For the 1769-L33ER, that means pulling this controller out of the generic MRO bucket and treating it explicitly in your supplier dialogues. You should agree on expected volumes, preferred alternatives, and escalation paths. Vendor scorecards that track on-time delivery and responsiveness for this catalog number, not just across the entire relationship, will help you separate anecdote from data when things get tight.

Use Domestic And Alternative Sources Wisely

Plex and Intellichief both underscore the role of geography. Domestic suppliers usually offer shorter and more predictable logistics lead times than overseas sources, at the cost of a higher unit price. For a mid-range controller, that trade-off is often justified once you factor in downtime risk, customs delays, and the administrative load of dealing with cross-border returns or failures.

At the same time, RELEX points out that alternative suppliers can be invaluable when certain regions are hit by holidays, weather, or regulatory changes. Their guidance around events such as Lunar New Year is instructive: retailers that plan for factory shutdowns months in advance and gradually build inventory stay ahead of availability shocks, while those that ignore the calendar scramble with backorders.

In the automation world, the same thinking applies to catalog items like the 1769-L33ER. You do not want to be evaluating new surplus vendors for the first time when your primary distributor has just pushed your expected ship date out by several weeks. Pre-qualify backup sources now, understand their firmware and return policies, and establish the internal process for using them so you are not improvising under pressure.

Automate The Paperwork, Not Just The Panel

Intellichief documents how manual order entry and approval workflows inflate lead times. They describe cases where intelligent capture and automated routing cut document-processing times from days to minutes. StockIQ and MRPeasy make similar arguments for integrated inventory and order management systems.

Applied to the 1769-L33ER, the lesson is simple. If engineering must fill out a spreadsheet, email purchasing, wait for internal approvals, and then have someone re-key data into an ERP system, you are adding days of internal lead time before your supplier even sees the order. When you automate the front end of that process, your procurement lead-time clock can start within minutes of maintenance deciding a spare needs to be ordered.

For controllers, which are typically low-volume but high-impact items, it often makes sense to create predefined requisition templates, budget pre-approval, and even automatic reordering rules when stock falls below a threshold. Inventory planning tools highlighted by StockIQ and RELEX can include these items in their optimization logic alongside higher-volume SKUs.

Tighten The Dock-To-Stock Window

Although procurement dominates the overall lead time for controllers, the time from when a box hits your dock to when the contents are available in your storeroom still matters. Articles on warehouse performance and dock-to-stock efficiency emphasize that manual receiving, paper-based processes, and poor integration between warehouse systems and ERP add needless lag.

Axelent’s discussion of real-time inventory tracking and advanced warehouse management systems shows that RFID, barcode scanning, and tight WMS–ERP integration can bring receiving and put-away times down significantly. Dock-to-stock improvement briefs further recommend using advance ship notices so that receiving can prepare documentation and labor before a truck arrives, and using barcode scanning to cut data entry at the dock.

For a 1769-L33ER, the concrete move is to flag the PO so that receiving and inventory teams treat it as a priority. As soon as it arrives, it should be inspected, booked into the correct maintenance location, and visible in the system. In many plants this is a matter of disciplined process rather than new technology, but the underlying principle is the same: if you have paid for the controller and it is sitting in a staging area unrecorded, it is functionally unavailable.

Managing Risk For Existing Installations

Planning for new projects is only half the story. Many plants already have a large installed base of 1769-L33ER controllers. For them, availability is directly tied to operational risk.

The supply-chain statistics mentioned earlier, such as disruptions costing about 8 percent of annual revenue on average, illustrate the magnitude of the stakes. A failed CPU on a key line can eat through that percentage very quickly if you have no spare on site and are staring at an uncertain lead-time quote.

One of the first tasks any maintenance or engineering leader should undertake is to inventory where these controllers sit and how critical each one is. Lines where an L33ER is paired with custom code, specialized I/O, or tightly integrated third-party modules deserve special attention. In some cases, as Hardy Solutions describes for multi-scale weighing systems, a controller coordinates complex weight processing and process control; replacing it is not as simple as swapping a generic digital I/O card.

Rockwell Automation’s own Product Lifecycle Search tool gives you an official view of where a catalog number sits in its lifecycle. It is worth noting that Rockwell’s AI-based navigator is explicitly labeled as informational only and does not override official product documentation. The company states that AI content may contain errors or may not reflect the latest developments, and that product documentation and professional advice remain authoritative. When you are basing a migration plan on lifecycle status, always defer to the underlying lifecycle data and manuals, not to conversational summaries.

If you resort to secondary or surplus channels to secure additional 1769-L33ER units, the firmware and software points from PDF Supply’s disclaimer become critical. They warn that hardware may ship with existing firmware on board and that they make no representation about your legal right to use that firmware. They also state that they do not sell any software required to program the hardware. In practice, that means you must have your own Rockwell software licensing in place, must verify firmware revision compatibility with your existing systems, and may need to flash controllers to the correct revision before deployment.

A Practical Playbook For Plants And Projects

Bringing these threads together, a pragmatic strategy for the 1769-L33ER revolves around a few concrete moves, executed deliberately rather than reactively.

First, treat the controller as a named A-class item in your inventory and risk registers. Document where it is installed, what each instance controls, and what the financial impact of downtime would be. Establish a target service level that reflects that risk and accept the carrying cost of a small number of spares as part of your reliability strategy.

Second, measure the real lead time you experience for this specific catalog number, by supplier. Track both the average and the spread. If one channel routinely delivers within a week from order and another oscillates between immediate shipment and multi-week delays, that data should drive your preferred-supplier and escalation decisions.

Third, line up your sourcing options before you are in crisis. Confirm who your authorized distributors are, what their policies are on forecasting and reservations, and what they can commit to in terms of stocking programs. In parallel, establish relationships with a small number of reputable secondary sellers, fully aware of the firmware and software caveats, and capture those rules in your maintenance and procurement standards.

Fourth, remove your own organization as a bottleneck. Replace manual requisition and approval chains with configured workflows in your ERP or inventory planning tools. Ensure that every controller you purchase is visible in the system and stored where maintenance expects to find it. Apply the same lean and continuous-improvement mindset that MRPeasy and other manufacturing sources recommend for production processes to your spare parts processes.

Finally, keep lifecycle and migration in view. Controllers like the 1769-L33ER do not stay current forever. Monitor official Rockwell lifecycle information, relate it to your installed base, and incorporate controller migration paths into your capital plans. It is easier to secure and standardize spares while a product is in its active or active-mature phase than after it transitions further along the lifecycle curve.

FAQ: Common 1769-L33ER Availability Questions

Is it safe to buy used or surplus 1769-L33ER controllers?

Surplus channels can be a useful safety valve when authorized distribution is short on stock, but you have to go in with clear eyes. As PDF Supply’s legal notices make clear, many resellers are not authorized by the OEM, cannot guarantee firmware revision, and do not sell the programming software you need. From a systems integrator’s perspective, that means you should always plan to verify hardware condition on a test bench, check firmware against your standard, and rely on your own Rockwell software licenses. For less critical spares or non-production test rigs, surplus can be perfectly acceptable. For highly critical lines, you will want tighter controls and thorough incoming inspection.

How many spare 1769-L33ER units should a plant keep?

There is no universal number that works for every facility, and it would be misleading to pretend otherwise. The right quantity depends on how many of these controllers you have in service, how critical those lines are, what lead times you actually experience from your suppliers, and how much commonality you have in your program designs. Research from ABC Supply Chain suggests framing the question in terms of service level and inventory turnover. For a controller that can stop a major line, it is often rational to maintain enough spares to cover at least the realistic worst-case lead time you see in your data, even if that means very low turnover.

How can I tell if a quoted lead time for a 1769-L33ER is realistic?

You can improve your odds by grounding your expectations in historical data and by maintaining supplier scorecards. MRPeasy advises calculating average lead times and their variability over several months of orders for each supplier. If a promised lead time is significantly shorter than what you have seen in practice, ask what has changed in their supply situation. Conversely, if a new quote is suddenly much longer, press for specifics and contingency options. Insights from StockIQ and RELEX highlight that leading practitioners monitor average lead time and on-time delivery as continuous KPIs, not just as occasional anecdotes, and they adjust sourcing and safety stocks accordingly.

Closing

Availability of the Allen Bradley 1769-L33ER is no longer something you can leave to chance or last-minute scrambling. If you treat this controller as the critical asset it really is, define and measure your lead times, and build a deliberate sourcing and stocking strategy around it, you turn an uncomfortable vulnerability into a manageable engineering and supply-chain problem. That is the kind of quiet, reliable work that keeps projects on track and production running when everyone else is wondering why their lines are still down.

References

- https://www.plctalk.net/forums/threads/check-communication-load-of-compact-logix.134380/

- https://www.nexinstrument.com/1769-l33er

- https://www.quicktimeonline.com/1769-l33er

- https://abcsupplychain.com/optimize-reduce-inventory/

- https://www.ebay.com/itm/315027618006

- https://www.fcbco.com/blog/dock-to-stock-efficiency-ideas

- https://www.hardysolutions.com/en/stock-inventory-management

- https://www.intellichief.com/strategies-to-reduce-the-lead-time/

- https://www.plccable.com/allen-bradley-1769-l33er-a-compactlogix-ethernet-processor/?srsltid=AfmBOopPKgcnvzVOoL1ZatMbTVTsmfLVVHelqmi7RtBWVqSzcfAFU1XE

- https://www.plcdcspro.com/products/allen-bradley-1769-l33er-a-compactlogix-5370-l3-controller-module

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment