-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Bulk Order Automation Components: Cost Savings Strategies

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

As a systems integrator who has spent years living inside control panels and project schedules, I can tell you that the cost of automation hardware is only half of the story. The way you specify, order, receive, and manage bulk component buys can quietly add more cost than many engineering teams realize. The good news is that those same processes are where some of the cleanest, most defensible savings sit.

This article looks at bulk ordering for industrial automation and control hardware through a pragmatic lens: how to cut total cost without starving projects or risking uptime. The perspective is hands-on, grounded in project delivery, and backed by research on procurement, supply chains, and order automation from sources including Deloitte, Invesp, Netguru, B2BWave, Hopstack, Sievo, and others.

The Hidden Cost Of Bulk Component Orders

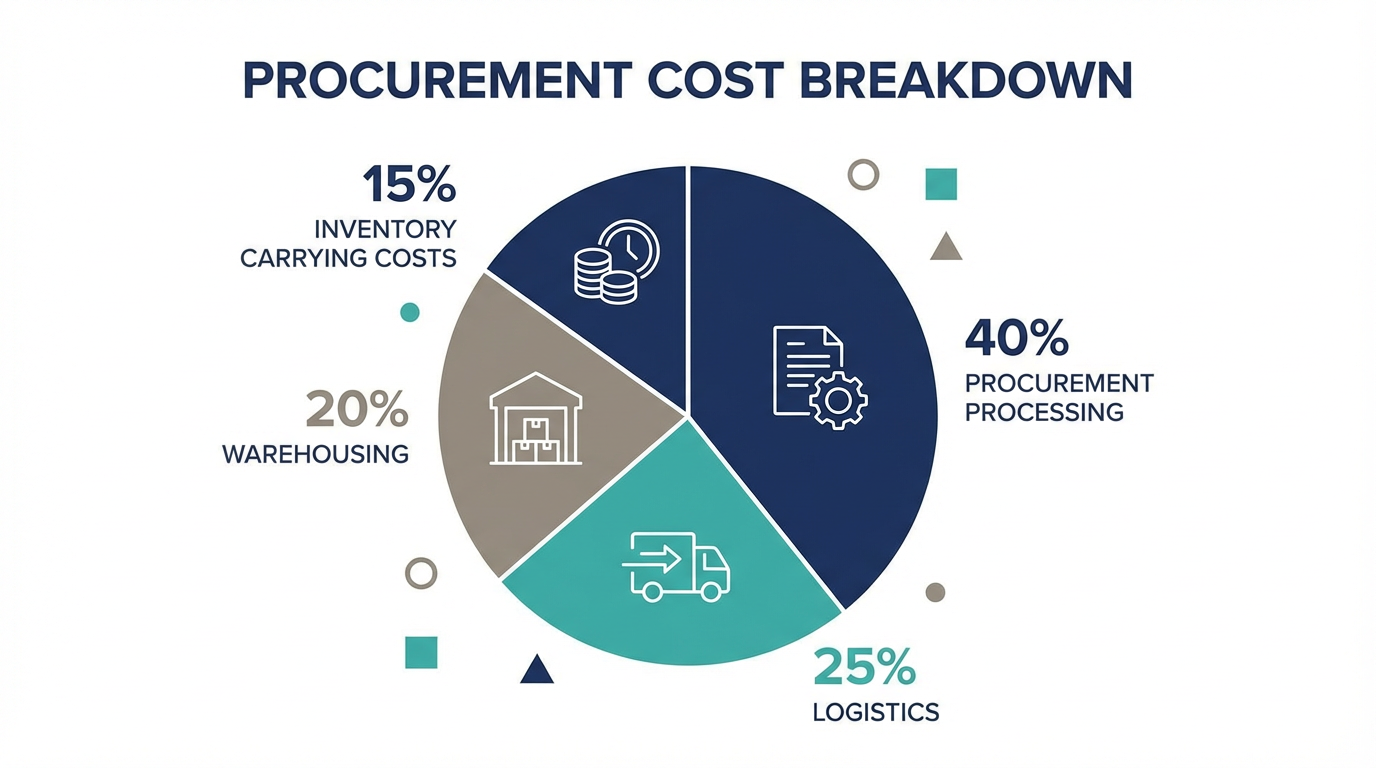

When teams talk about “saving on components,” the conversation usually starts and ends with unit price. For large projects, that matters, but research on procurement and supply chains shows that the process costs around those parts are just as important.

Procurement-managed expenditure often accounts for roughly two-thirds to three-quarters of a company’s total outflows according to procurement cost-reduction research. That spend passes through purchasing, logistics, finance, and warehouse operations, so every bit of friction in those workflows turns into real money.

Manual order management is one of the biggest hidden cost drivers. Research summarized by Netguru describes a typical manually processed purchase order costing around $30.00 to $60.00 in labor and taking eight to twelve hours end to end. With automation, that same order can drop to about $5.00 to $10.00 and often closes in fifteen to thirty minutes. When you are issuing thousands of orders a year for sensors, drives, PLCs, and panels, that delta is no longer “process noise”; it is a budget line.

Order handling is not the only load. Fulfillment research from Hopstack indicates that picking, packing, shipping, and related overhead can account for about fifteen to twenty-five percent of net ecommerce sales and roughly half to two-thirds of logistics costs. Component distributors and manufacturers see the same pattern when every small order triggers its own pick, pack, and ship event instead of being consolidated or planned.

At the same time, the B2B buying context is changing. DCKAP reports that global B2B ecommerce is projected to reach about $25.65 trillion in the next few years, with buyers increasingly preferring digital self-service and often operating rep-free. B2BWave notes that manual wholesale processes built on spreadsheets, PDFs, and email are slow, error-prone, and hard to scale. In that environment, teams that still manage bulk component orders by email chains and ad‑hoc spreadsheets are paying in higher internal costs and in lost opportunities with digital-first customers.

The bottom line is straightforward. If you only negotiate better discounts on components but leave order capture, approvals, logistics, and inventory management untouched, you are leaving a large portion of potential savings on the table.

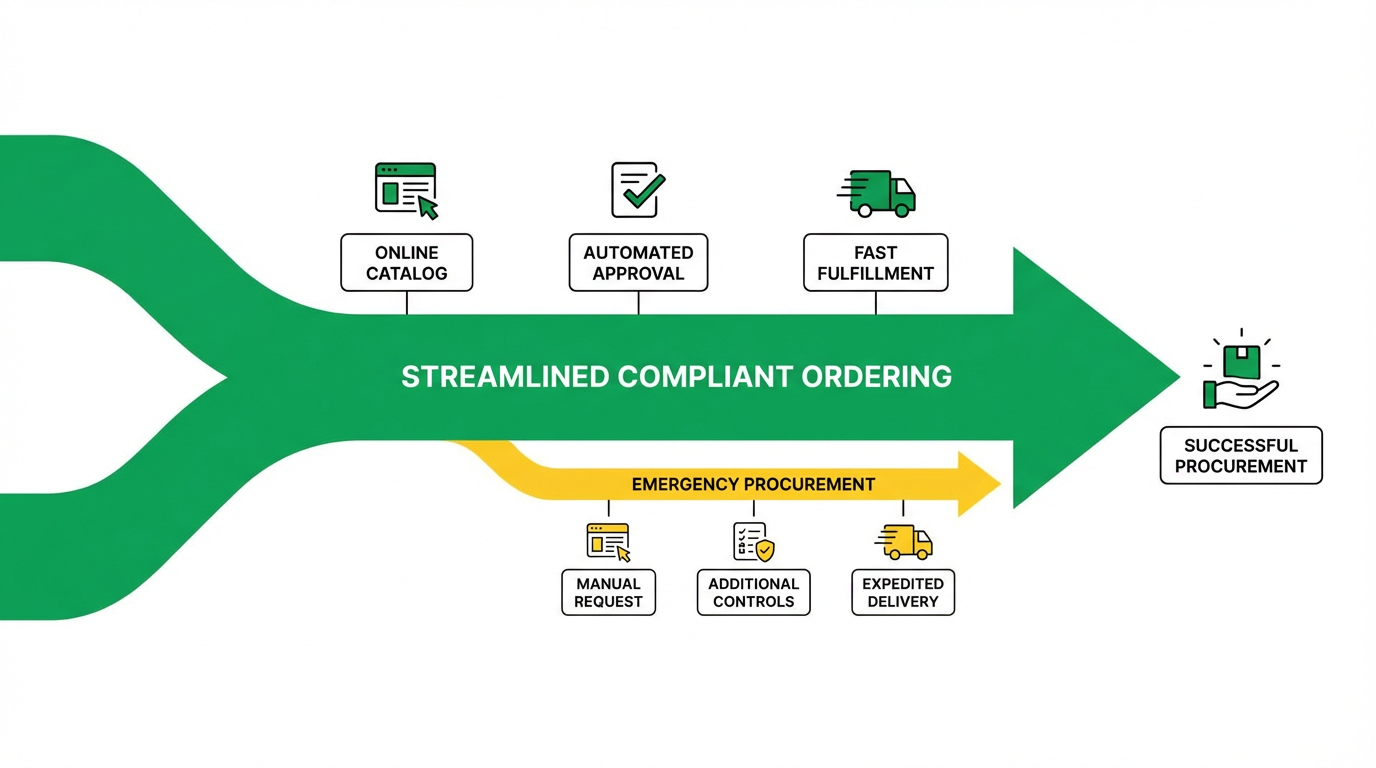

Strategy 1: Automate How You Capture And Approve Bulk Orders

Replace Email Orders With A Digital Front Door

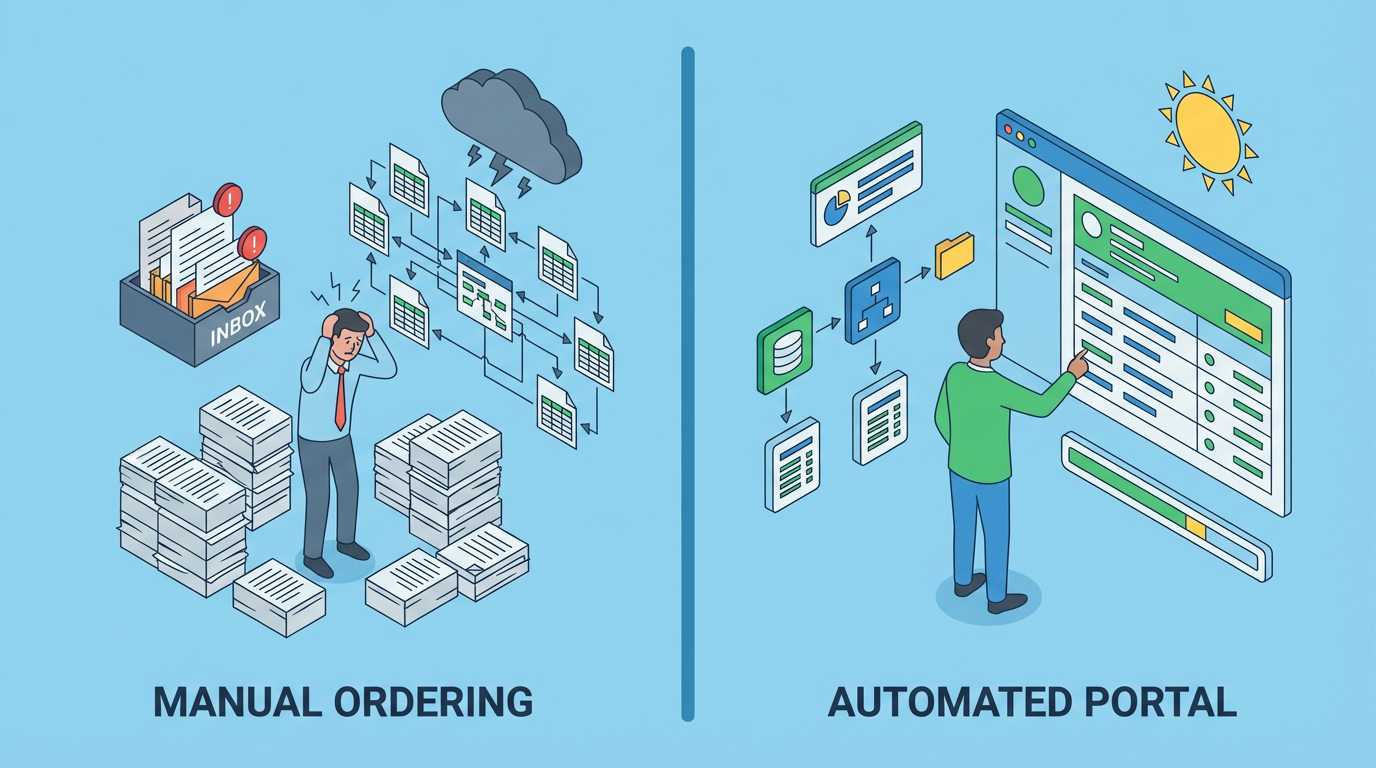

On many projects I have joined late, the first “automation problem” was not on the plant floor; it was in the purchasing team’s inbox. Orders were arriving as spreadsheets, PDFs, and free-form email text. Someone in procurement retyped that information into an ERP or accounting system, checked prices by hand, and emailed confirmations. Every quote change or revision meant another round of manual edits.

B2BWave describes this traditional wholesale ordering pattern as time-consuming, error-prone, and difficult to scale. Their research indicates that automating the wholesale order process can make operations about forty‑three percent faster by cutting time spent on email and manual tools. They also highlight that manual invoicing commonly carries error rates between one and three percent, with each mistake taking from twenty minutes to several hours to resolve and slowing cash flow.

For bulk automation component orders, a digital front door usually means a B2B portal or order platform where:

You present contract pricing, approved part numbers, and availability to each customer or internal plant.

Engineers or buyers can upload bills of material, assemble recurring orders, and see what is in stock.

Orders flow as structured data directly into ERP, inventory, and fulfillment systems.

This removes copy‑paste work, cuts order-entry errors, and forces needed discipline on part numbers and alternates. In a controls hardware context, it also reduces misorders of near-identical SKUs, which can be extremely expensive to unwind late in a project.

There is an external pressure angle as well. B2B research cited by B2BWave notes that ninety percent of B2B buyers are willing to switch suppliers because of a poor digital experience. If your component business or internal shared-service team still expects buyers to send bulk orders by email, you are not just accepting higher costs; you are making it easier for someone with a proper portal to win that business.

Use Purchase Order Automation To Cut Transaction Cost

A strong front-door experience is only half of the picture. The other half is what happens inside once a requisition or cart is submitted.

Hyperbots defines purchase order automation as the use of digital workflows integrated with ERP or accounts payable systems to create, route, approve, and track purchase orders. Their analysis highlights lower processing cost per PO, reduced errors and disputes, better spend control, and stronger compliance as the main return-on-investment drivers. The same piece points to claims of up to about eighty percent reduction in PO processing costs compared with manual workflows.

Netguru’s work on order management automation supports this scale of savings with concrete numbers. They describe manually handled purchase orders costing tens of dollars and eight to twelve hours of staff time, versus low single-digit costs and under thirty minutes when the process is automated. Across a chain of two hundred stores, their example estimates managers losing around thirty thousand hours per year on manual ordering, worth close to a million dollars at typical pay rates.

Deloitte’s procurement research, cited in DCKAP’s discussion of automated bulk ordering, suggests that procurement process automation can cut costs by up to thirty percent and boost efficiency by nearly forty percent. Those numbers align with what I have seen over multiple rollouts: once approvals, catalog selection, and PO creation happen automatically, the finance and purchasing teams stop acting as human routers and focus instead on exceptions and supplier performance.

For bulk automation components, that kind of automation usually includes standardized BOM templates, contract pricing rules by project or customer, built‑in budget checks, and automatic creation of POs and change orders when engineering revisions land. The key is to automate the repetitive, rules-based flow while keeping human review on genuinely unusual or high‑risk items.

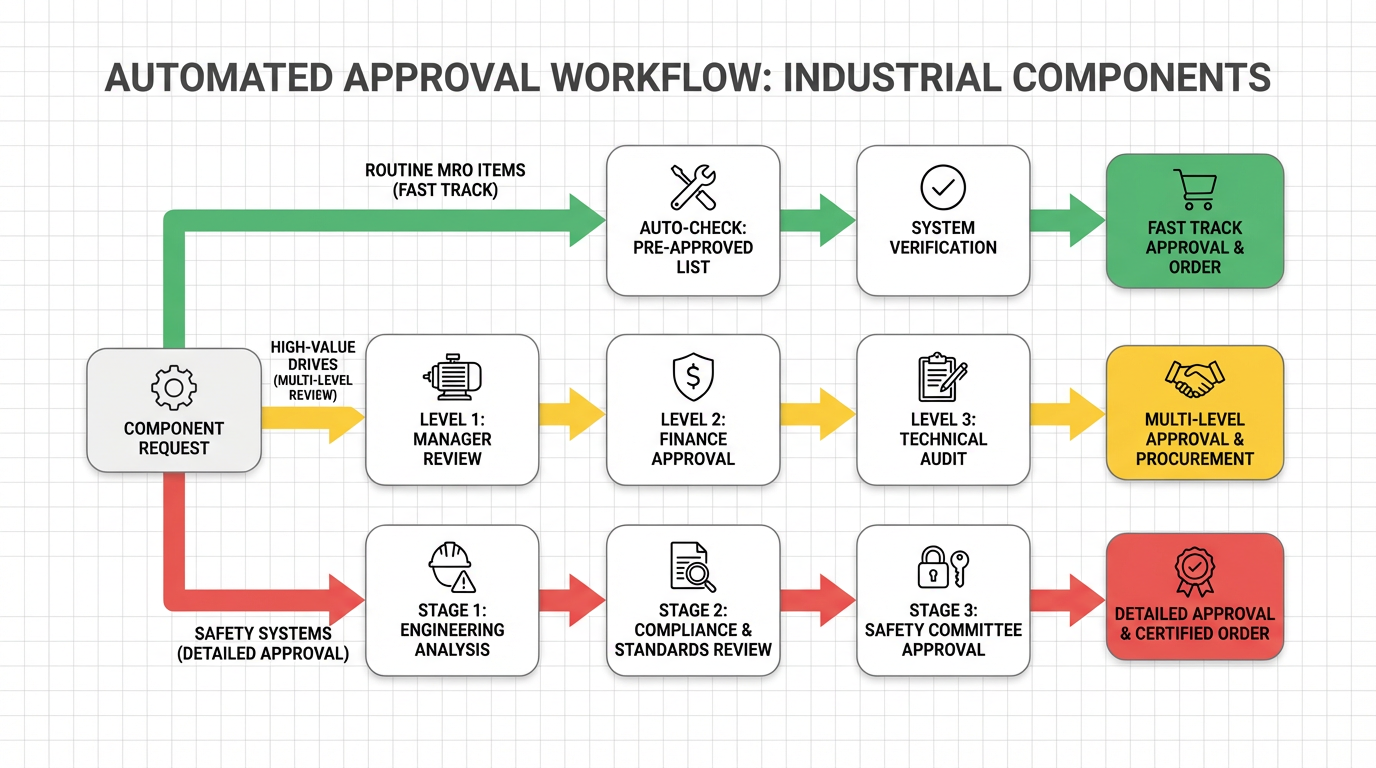

Tighten Approvals Without Slowing Projects

Engineering teams worry that additional approval layers will slow projects and delay critical hardware. Finance teams worry that loosening approvals to protect schedules will open the door to uncontrolled spend. With manual workflows, both fears are valid: long email chains act as bottlenecks, and “just get it done” exceptions become permanent habits.

Versa Cloud ERP’s procurement guide reports that more than sixty‑five percent of procurement leaders see delayed approvals as a barrier to agility, and that manual chains become backlogged without clear tracking. The same source recommends automated approval workflows with parallel routing, rule‑based escalations when thresholds or time limits are exceeded, and real-time visibility into bottlenecks.

Order.co’s work on procurement savings extends this idea. They advocate clear spend policies, role-based spending limits, and approval thresholds tied to order value, category, location, or role, combined with automation that enforces those rules. Their case studies show that once approval logic is embedded in the system, organizations can reduce maverick spending and improve catalog compliance while still moving routine orders quickly.

Applied to bulk automation components, a pragmatic pattern is to define different approval rules for different categories.

Routine MRO items and standard panel components within contracted pricing can flow with light-touch approvals or even be touchless. High-value items such as drives, safety systems, or specialized instrumentation that materially affect project risk or margin can trigger additional review, but that review is automated and visible rather than buried in email.

Strategy 2: Smarter Inventory For Automation Hardware

Having the right components on the shelf often decides whether a maintenance shutdown ends on time or drifts into overtime and lost production. At the same time, overstocking automation hardware ties up cash in high-value items that may sit in stores for months. Research on supply chains and inventory shows that this tradeoff is one of the biggest levers for structural cost reduction.

Erbis cites Invesp in noting that companies with well-optimized supply chains see about fifteen percent lower supply chain costs, hold less than half the inventory of peers, and achieve cash-to-cash cycles at least three times faster. LSI and other sources emphasize that inventory and warehousing are core cost components alongside procurement and logistics, and that just‑in‑time practices and better forecasting reduce both storge and financing burdens.

Balance Bulk Discounts And Carrying Costs

Bulk purchasing is tempting in the automation world, especially when vendors offer attractive volume breaks on high-ticket items. Simfoni and LSI both stress that procurement cost reduction is not just about unit-price cuts but about the total cost across purchase planning, contracts, logistics, inventory, and payment. Holding too much stock introduces storage, insurance, depreciation, and obsolescence costs that quickly erode savings from volume discounts.

A more sustainable approach is to classify components by demand pattern and risk, then choose bulk or lean strategies accordingly. Fast-moving items required on nearly every panel build may justify larger buys. Slow-moving, project-specific components are better ordered closer to need using tighter forecasts and supplier lead-time commitments.

Erbis and Unleashed both highlight FSN analysis as a useful tool: classifying items as fast, slow, or non-moving to guide storage layout and disposal decisions. For automation hardware, this often means acknowledging that some items that engineers love to keep “just in case” belong in slow-moving or clearance status and should be rationalized rather than endlessly reordered.

Use Just-In-Time Where Risk Is Low

Just‑in‑time inventory practices, described in detail by LSI, Unleashed, and Invensis, align inventory levels with actual demand to reduce holding costs. In manufacturing exemplars such as Toyota’s production system, materials arrive only as needed for production.

In a controls and automation context, JIT is most effective where:

Lead times are predictable and not excessively long.

Alternative sources exist in case of disruption.

The cost of a stockout is manageable or can be mitigated with temporary workarounds.

That often means applying near‑JIT practices to commodity items such as wiring accessories, standard terminals, and commonly used I/O modules, while maintaining more conservative buffers for safety-critical equipment or devices with long lead times.

The supporting requirement is accurate demand forecasting. Articles from Erbis and LSI stress that demand forecasting and inventory turnover analysis are core to avoiding both stockouts and excess. When you can see true consumption by SKU across projects and plants, JIT stops being a buzzword and becomes a calculated decision about how much risk you are willing to carry.

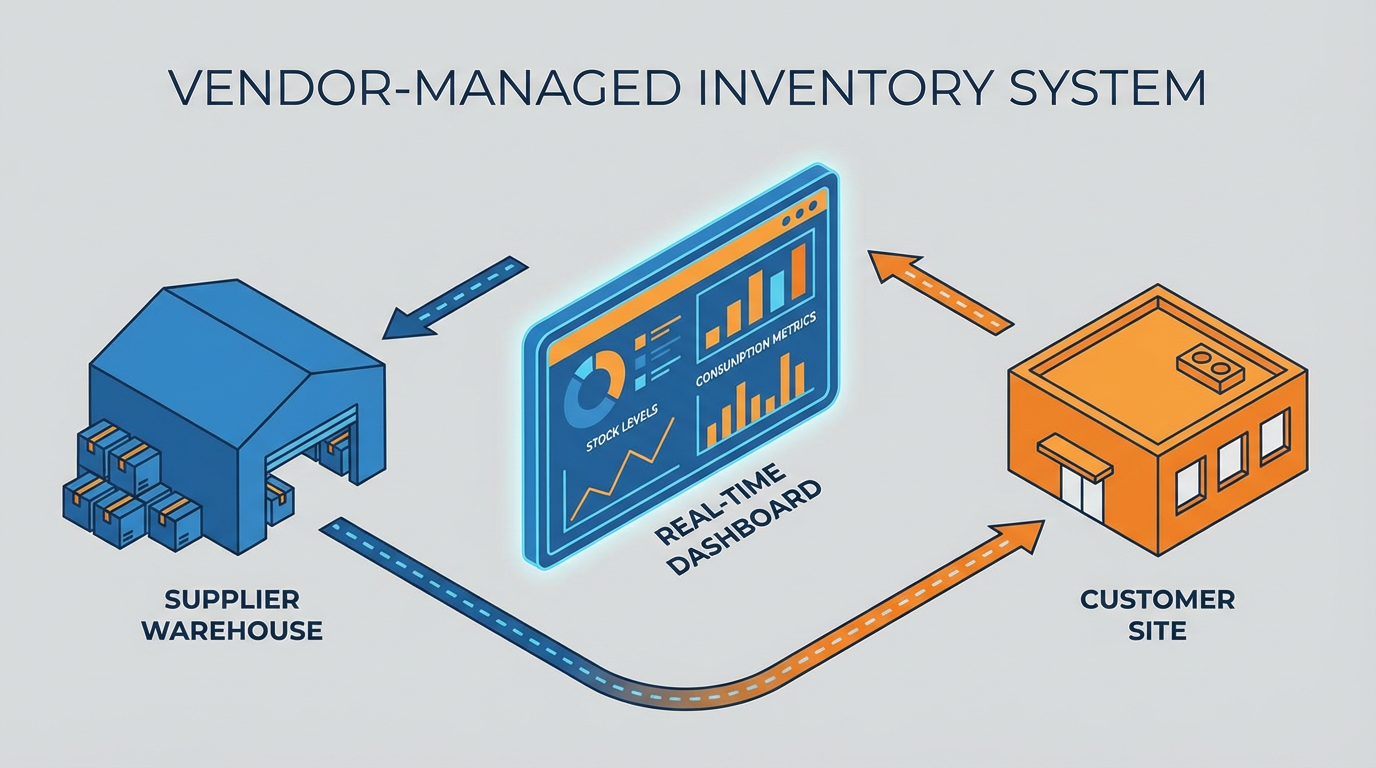

Consider Vendor-Managed Inventory And Consignment

Unleashed describes Vendor Managed Inventory as a model where the supplier takes responsibility for maintaining stock levels, using shared demand data to replenish inventory. Consignment inventory goes a step further and allows stock to sit at the customer’s site while ownership remains with the supplier until consumption. Both models reduce working capital and storage risk for the customer.

For automation components, VMI and consignment work well for standardized, high-volume parts such as enclosure hardware, common sensors, and safety devices that appear on nearly every project. When the supplier is motivated to keep those bins full and has real consumption data, you get the operational benefit of bulk buying and the financial benefit of reduced on-book inventory. The trade-off is tighter dependency on the supplier and the need for transparent performance metrics and service-level expectations, which are manageable if you treat these arrangements as structured category strategies rather than informal favors.

Strategy 3: Reduce Fulfillment And Logistics Cost Per Order

Once an order is placed and approved, cost still accumulates in inbound freight, receiving, storage, picking, packing, shipping, and returns. Hopstack’s analysis of order fulfillment costs emphasizes that these steps collectively can account for a significant share of logistics spend, and that even small efficiency gains produce meaningful margin improvement.

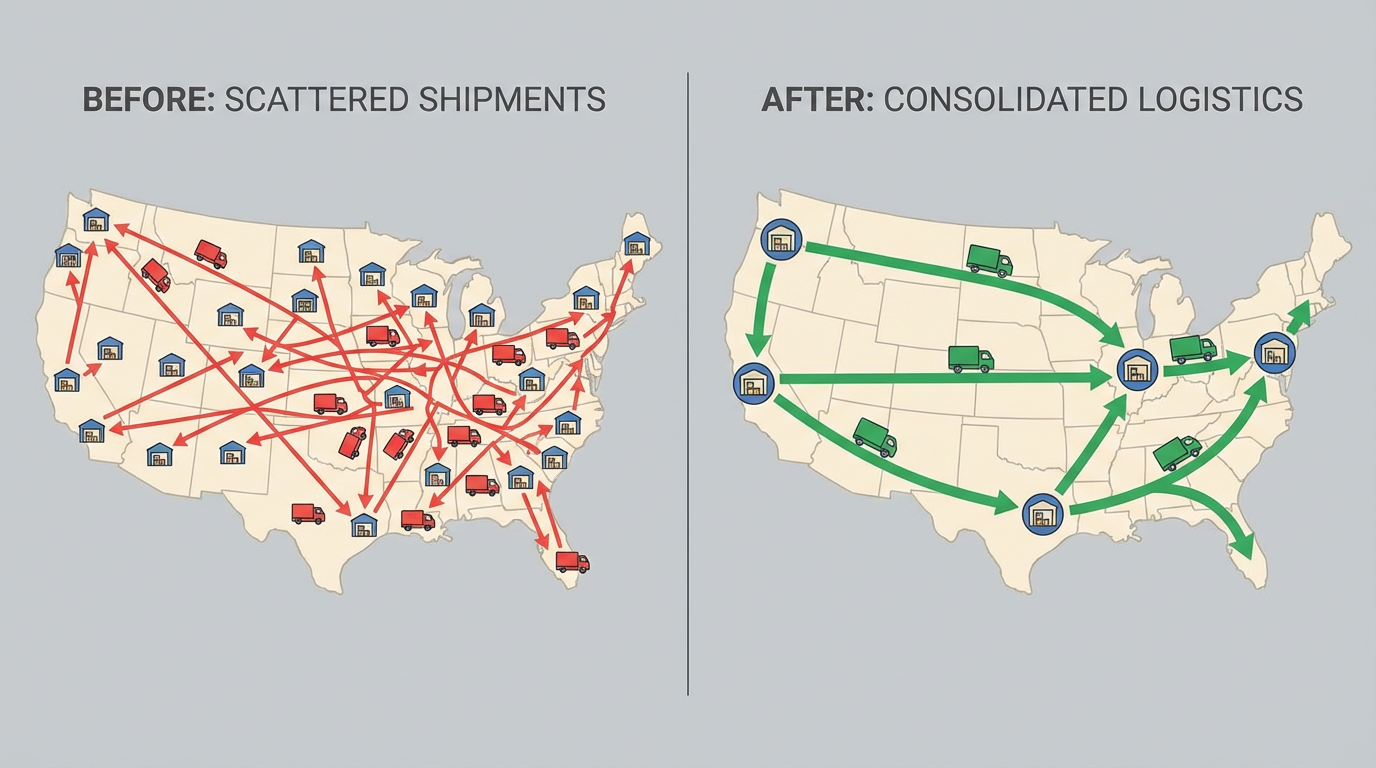

Consolidate Shipments And Optimize The Network

Case studies compiled by Logistics Bureau show what is possible when companies redesign networks thoughtfully. Deere & Company, for example, reduced inventory by about one billion dollars, cut delivery lead times in half, and saved around five percent annually on transportation by adding merge centers, optimizing cross-docks, consolidating shipments, and expanding third-party logistics use. AGCO achieved roughly eighteen percent freight cost reduction in eighteen months and about a twenty-eight percent cut in inbound logistics costs by implementing a European logistics control tower with a transportation management system and strategic 3PL partnership.

Although those examples come from heavy equipment, the pattern applies directly to automation components. Many manufacturers and distributors still ship partial orders as soon as items arrive, generating multiple small shipments to the same plant or integrator site. Others run multiple warehouses without a clear view of which location should serve which demand.

Combining better order management automation with logistics intelligence allows you to:

Hold and consolidate non-urgent component lines into fewer, fuller shipments.

Route bulk orders through regional hubs closer to the consuming plants.

Use TMS capabilities to select carriers and modes based on cost and performance.

The result is fewer touches, lower freight per line item, and more predictable delivery windows, all of which control cost without sacrificing service.

Improve Warehouse Efficiency For Small Parts

Automation components tend to be small, high-value items that can be easily misplaced and require careful picking. Hopstack’s recommendations for warehouse cost reduction are well-suited here. They emphasize optimizing layout and slotting based on item velocity, using batch, wave, or zone picking to reduce travel time, standardizing work instructions, and using barcode or RFID scanning.

LSI and Erbis add that warehouse layout, automation technologies like conveyors or automated storage and retrieval, and better space utilization are key levers for lowering labor and facility costs. Even without heavy capital investment, simply re‑slotting fast-moving components closer to packing stations, standardizing bin labels, and using handheld scanners can reduce mispicks and shorten picking paths.

From a systems integrator’s perspective, accurate, efficient picking has a direct project impact. When the right components arrive in the right quantity and sequence, build teams are not stopped by missing terminals or mismatched I/O modules, and you avoid premium freight and expediting to recover from warehouse errors.

Decide When To Use Third-Party Logistics

Hopstack notes that for brands exceeding in‑house capacity or dealing with volatile demand, outsourcing some or all fulfillment to third‑party logistics providers is often recommended. While this trades some per‑order margin for lower capital expenditure and faster scaling, it can make sense when your growth in automation components outpaces your ability to invest in warehouses and systems.

A hybrid model is common: keep strategic or high‑complexity items in-house while using 3PLs for standardized items or certain regions. The cost-saving angle comes from shifting fixed costs into more variable, usage-based fees and leveraging the 3PL’s network, carrier contracts, and technology stack, which few single manufacturers could justify on their own.

Strategy 4: Strategic Procurement And Supplier Management

Process automation and logistics optimization deliver quick wins, but long-term structural savings in bulk component buying depend on how you manage categories, suppliers, and contracts.

Build Category Strategies Around Automation Spend

Sievo and Simfoni both emphasize category management: grouping spend into coherent categories managed holistically through their lifecycle. For automation hardware, obvious categories include sensors, safety devices, PLC and PAC platforms, drives and motion, control panels and electrical distribution, and services such as panel fabrication.

Order.co underscores the importance of understanding which categories represent the largest spend and focusing effort there. They advocate regular spend analysis, category management for big-ticket areas, and benchmarking to find savings opportunities. Versa likewise stresses that fragmented, manual procurement processes and lack of visibility lead to missed savings and strained supplier relationships.

In practice, a category strategy for automation components might define preferred product families, standardize on a limited number of PLC platforms, and align panel designs to those standards. EMA’s engineering cost reduction article reports that consolidating volumes with fewer, higher-volume parts can yield fifteen to twenty-five percent savings in procurement due to better pricing and protection against future price hikes.

The risk, and this is where experience matters, is over-standardizing in ways that reduce flexibility or lock you into suppliers whose roadmaps no longer match your needs. Category strategies must remain living documents, revisited as technology and markets move.

Eliminate Maverick Spend And Leakage

Several sources, including Sievo, Order.co, and Versa, describe maverick or rogue spend as purchasing outside agreed contracts and processes. Versa notes that off-contract spending can inflate costs by about ten percent or more annually when left unchecked. Such leakage is common in automation components when engineers or sites buy urgently needed parts on corporate credit cards or from local distributors outside of negotiated agreements.

Order.co suggests multiple tactics to contain this: clear policy education for stakeholders, enforcement of approval workflows, auditing of procurement costs and expense reports, and consolidating vendors so volume is not diluted across overlapping suppliers. Versa adds that embedding approval rules directly into systems, combined with spend analysis to detect off-contract transactions, is essential.

For control hardware, the practical compromise is to keep a narrow path for truly urgent buys while making the compliant route clearly easier and faster for most needs.

When buyers know that the catalog already contains the right sensors, drives, and enclosures at good prices, and that orders placed through the portal ship reliably, the temptation to go off-contract drops.

Renegotiate, Benchmark, And Standardize With Care

Netsuite, Sievo, and CostAnalysts emphasize that cost reduction in production and procurement comes not just from one-time negotiations but from ongoing contract review and benchmarking. Netsuite notes that lean manufacturing initiatives can reduce costs by about five to twenty percent in the first year while improving quality, and those gains are often linked to better supplier collaboration and contract design.

Sievo recommends revisiting contracts older than a few years, benchmarking pricing, adjusting payment terms, and exploring volume-based discounts. EMA’s work on engineering cost reduction points out that investigating alternative components during design can cut costs by twenty to thirty percent by replacing overspecified or premium parts with functionally equivalent alternatives, provided requirements are truly understood.

For bulk automation hardware, this means challenging legacy specifications where appropriate, consolidating to common part families where it does not compromise functionality, and using data from spend analysis and supplier performance to negotiate more effectively. It also means involving engineering early so that cost-saving component substitutions do not introduce unacceptable risk or late-stage redesign.

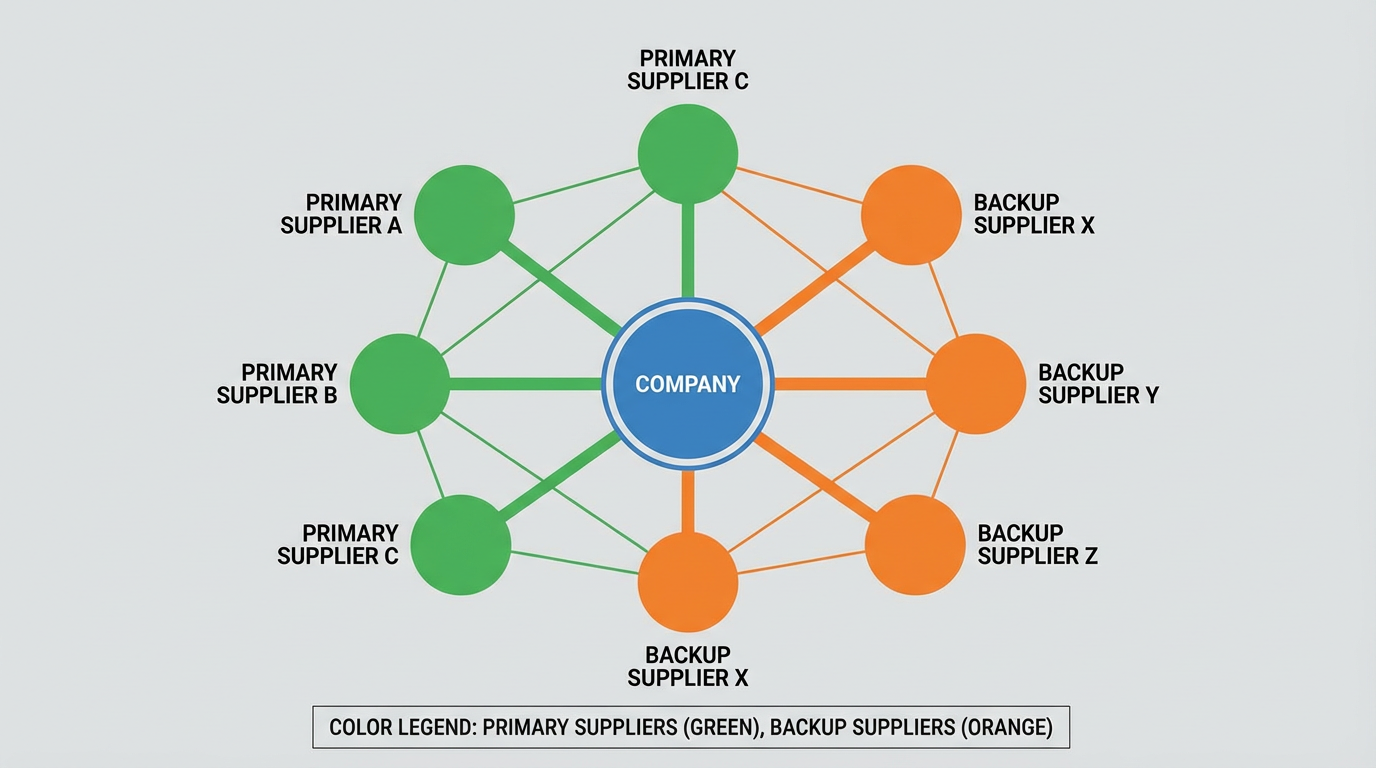

Manage Risk As A Cost Line

Procurement and supply risk is often treated as a separate concern from cost, but multiple sources argue that risk reduction is itself a form of savings. Sievo notes that managing risks such as sole-supplier dependence and emergency buys leads to cost avoidance, even if it does not always show up as hard savings.

DCKAP highlights cybersecurity risk in large B2B orders, citing high-profile ransomware losses reported by law-enforcement agencies. Versa discusses supplier risk and the value of predictive analytics for monitoring demand and risk signals. EMA stresses that building a resilient supply chain during design, including second-sourced and lifecycle-stable parts, can deliver ten to twenty percent savings by avoiding redesigns and downtime.

In the automation hardware world, that translates to policies such as avoiding single-sourced safety devices when possible, checking component lifecycle status when designing panels, and distributing volume across multiple authorized distributors so that a single disruption does not stall projects.

While these steps may not immediately reduce unit prices, they reduce the probability of very expensive fire drills down the road.

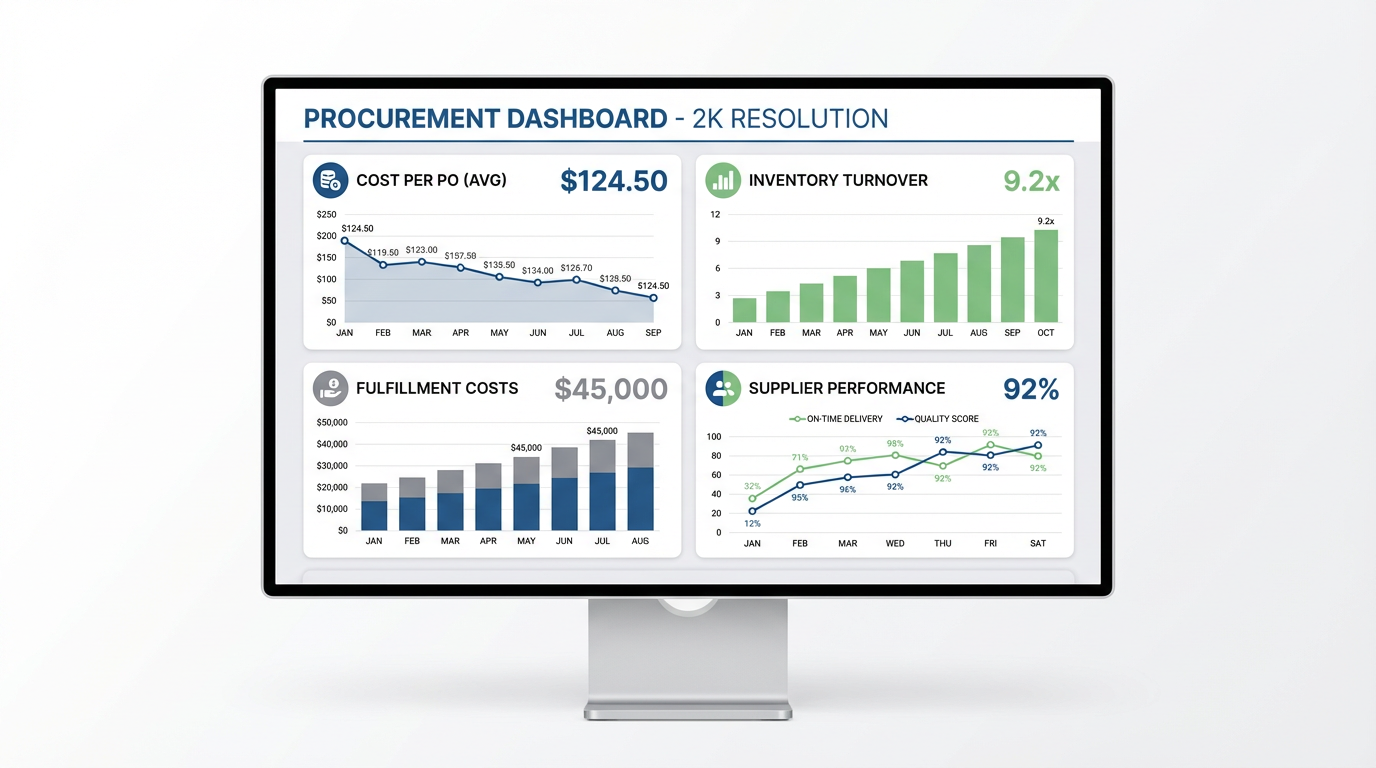

Strategy 5: Use Data And KPIs To Keep Savings Real

You cannot manage what you do not measure. That cliché becomes painfully real when leadership asks, a year after a big procurement or order-automation initiative, whether the promised savings are actually materializing.

Erbis, LSI, Hopstack, Netguru, Order.co, and Versa all stress that clear KPIs and analytics are the backbone of sustainable cost reduction. Simfoni and Sievo go further, describing high-quality, timely data on spend and supplier performance as a prerequisite for any serious savings program.

What To Measure

Different teams will emphasize different metrics, but research across these sources converges on a core set that is especially relevant for bulk component orders.

A concise way to see them is in a simple comparison table.

| Area | Example metrics and research context | Why it matters for automation components |

|---|---|---|

| Order and PO processing | Cost per PO, PO cycle time, percentage of POs processed touchless; Netguru notes large drops in cost and hours with automation. | Shows whether order automation is delivering the expected labor and time savings on high-volume component buys. |

| Procurement compliance | Percentage of spend under contract, maverick spend rate; Versa and Order.co both link poor compliance to ten percent or more extra cost. | Highlights leakage from preferred suppliers and catalogs and helps enforce part and supplier standardization. |

| Inventory efficiency | Inventory turnover, days of inventory, stockout rate, write-offs; Erbis cites optimized chains with lower inventory and faster cycles. | Indicates whether bulk-buy and JIT decisions for components are actually freeing cash and avoiding obsolescence. |

| Fulfillment and logistics | Cost per order, fulfillment cost as percentage of sales, order accuracy, return and rework rate; Hopstack shows fulfillment can be a major cost share. | Tracks the effect of warehouse optimization, consolidation, and automation on the total cost to move components. |

| Supplier and contract health | On-time delivery, quality incidents, contract renewal performance; EMA and Sievo emphasize supplier scorecards and benchmarking. | Helps justify supplier consolidation or diversification and underpins credible negotiations and risk management. |

These metrics should be visible to both operations and finance.

Versa, Erbis, and Order.co all advocate for integrated dashboards that consolidate enterprise-wide expenditure data, cleanse and categorize it, and provide interactive analytics so decision makers can understand where costs and savings are emerging.

Build A Continuous Improvement Loop

Research from Erbis, LSI, CostAnalysts, Netsuite, and Invensis all land on the same principle: cost reduction is not a one-time event but an ongoing discipline. That discipline usually includes regular audits of processes and energy use, benchmarking against peers, and a culture that encourages small, continuous improvements rather than sporadic large projects.

In a bulk automation components context, a practical loop might look like this. You baseline metrics for order processing cost, lead times, inventory levels, and fulfillment costs. You implement targeted changes, such as automating PO approvals for certain categories or consolidating shipments for a group of plants. You then measure the impact over several months, comparing to baseline and refining the process. If savings are real and stable, you roll the approach out to more categories, customers, or regions.

This is exactly the pattern illustrated in many of the case studies cited across the research, from Intel’s shift to make-to-order models that dramatically reduced order cycles and supply chain cost, to Starbucks and AGCO’s network redesigns that delivered hundreds of millions in savings over time. None of those companies relied on a single technical fix; they combined technology, process, and governance and kept iterating.

A Pragmatic Roadmap For Automation And Control Teams

Bringing all of this together into action does not require a big-bang transformation. In my experience as a systems integrator and project partner, the most reliable results come from picking a few high-impact areas and proving the value quickly.

For many automation hardware businesses and engineering organizations, the first step is simply to make the current order-to-cash and procure-to-pay processes visible. Map how a bulk component order moves from specification to PO to warehouse to panel shop, and collect honest numbers on how long each step takes and how often errors occur. Netguru, B2BWave, and Versa all stress that mapping and baselining the current process are critical precursors to any automation initiative.

The next step is to target a constrained pilot. That might be automating the wholesale order process for a handful of top integrator customers with a portal stocked with their standard parts. It might be automating internal POs for a specific category such as drives, where volume is high and approvals are predictable. Or it might be applying inventory optimization practices and better analytics to a single warehouse and category to reduce carrying costs without hurting service.

As the pilot proves out, with metrics that reflect lower cost per PO, reduced maverick spend, improved inventory turnover, or lower freight per shipment, you can take those numbers to finance leadership. At that point, you are no longer arguing for “digital transformation” in abstract terms; you are presenting hard evidence that each dollar invested in order automation, procurement tooling, or warehouse systems returns several dollars in savings or avoided cost.

From there, the job becomes one of careful scaling, continuous measurement, and staying honest about tradeoffs. Not every component category needs JIT. Not every supplier should be consolidated. Not every workflow should be automated if volumes are low or risk is high. But with the right data, governance, and mindset, you can turn bulk automation component ordering from a cost sink into a quiet source of sustainable savings and resilience.

FAQ

Q: How can I justify investment in order and PO automation for automation components to finance leaders?

A: Point them to the kind of results described in research from Netguru, Hyperbots, Deloitte, and Versa. Manual purchase orders often cost tens of dollars and many hours of staff time, while automation can reduce both cost and cycle time dramatically, with some analyses describing up to about eighty percent reduction in processing cost and procurement process automation cutting overall costs by as much as thirty percent and boosting efficiency by nearly forty percent. Combine those external benchmarks with your own baseline data on order volumes and labor time, then frame the automation project as a way to convert repetitive manual work into measurable savings and better control over component spend.

Q: Does it still make sense to buy in bulk once I automate ordering?

A: Yes, but the goal shifts from blanket bulk buying to targeted, data-driven volume aggregation. Research from Erbis, Unleashed, and EMA shows that consolidating volumes on selected parts and suppliers can deliver substantial savings, while excess inventory creates carrying costs and obsolescence risk. With automated ordering and good analytics, you can reserve bulk buys for fast-moving, stable items, while using just‑in‑time principles and tighter contracts for slower or riskier components.

Q: Where should a mid-sized systems integrator start if everything is currently manual?

A: Start where pain is most visible and savings can be measured quickly. Many integrators find that automating the way they accept and place bulk orders for standard hardware with a handful of key distributors is the most immediate win. Others begin with internal PO automation for their most common component categories. In either case, follow the pattern seen across the research: map the current process, define clear metrics, run a focused pilot, prove results, then expand gradually rather than attempting to automate everything at once.

As a veteran integrator, I have seen that organizations which treat bulk component ordering as a strategic process—and are willing to automate it thoughtfully—consistently deliver projects with healthier margins and fewer last‑minute surprises. That is what turns a supplier or engineering team into a reliable long-term partner in the eyes of both operations and finance.

References

- https://www.invensis.net/blog/cost-reduction-strategies-for-manufacturing-companies

- https://blog.hyperbots.com/maximize-purchase-order-automation-roi-proven-cost-savings-strategies-for-finance-leaders

- https://www.assemblymag.com/articles/88401-automated-assembly-a-practical-guide-to-low-cost-automation

- http://automore.in/how-automation-in-b2b-supply-chains-increases-efficiency-and-reduces-costs/

- https://www.b2bwave.com/p/how-to-automate-your-wholesale-order-process-without-losing-control

- https://www.costanalysts.com/manufacturing-cost-reduction/

- https://www.hopstack.io/blog/order-fulfillment-costs

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/cutting-costs-automation-case-study-savings-amit-mukherji-2wryf

- https://www.logisticsbureau.com/7-mini-case-studies-successful-supply-chain-cost-reduction-and-management/

- https://lsiwins.com/cost-reduction-in-supply-chain-management/

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment