-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Conformal Coated PCB Modules for Moisture Protection in Industrial Automation

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

In industrial automation, very few things are as frustrating as a control system that passes every factory test and then starts failing a few months into service because of moisture. The cabinet is “sealed,” the wiring looks clean, and yet the drive trips intermittently, the I/O module starts chattering, or the safety relay refuses to reset after a humid weekend shutdown.

Again and again, field investigations converge on the same culprits that industry articles from Altium, Cadence, SVTronics, and others describe: condensation, corrosion, and slow moisture ingress into printed circuit boards. Conformal coated PCB modules are one of the most effective tools to push those failures out of your operating life, rather than into your warranty period.

This article walks through how conformal coated PCB modules work, what they can and cannot do, and how to apply them intelligently in moisture-prone industrial control applications, from a systems integrator’s point of view rather than a chemistry lab’s.

Moisture And Condensation: The Real Enemy

Moisture is not just “water in the air.” It appears as vapor, thin surface films, droplets, and absorbed water inside materials. Each form creates different failure mechanisms.

Attabox’s work on electrical enclosures explains condensation clearly. Warm, humid air inside a control box contacts a cooler surface and crosses its dew point. Water condenses on that cooler metal door or backplate, then migrates or drips toward live conductors. Because control panels often contain heat sources such as variable‑frequency drives, servo amplifiers, transformers, and power supplies, they run warmer than the ambient environment, which sets up exactly the kind of temperature gradients that drive condensation on colder surfaces within the same enclosure.

SVTronics notes that even a “smallest droplet” on a PCB can warp the board, cause rust and corrosion, and create outright malfunctions. From a circuits point of view, that droplet plus dissolved contaminants acts as an unplanned conductor. Instead of staying on the copper trace you designed, current takes the easier path through the moisture film, causing shorts, arcing, and in worst cases total board failure.

Humidity by itself is just water vapor, but high humidity makes it much easier to reach the dew point on any cold surface. Altium points out that almost any environment short of a desert will see water condense on cool surfaces when humidity is high enough. This is exactly what happens in coastal plants, washdown areas, and poorly ventilated cabinets.

What Moisture Does To A PCB

Several of the cited sources converge on the same failure modes.

SVTronics defines moisture broadly as water or other liquid diffused into materials or condensed on surfaces. When that liquid contains dissolved salts and flux residues, it becomes far more conductive than pure water. Cadence notes that moisture on PCBs and assembled assemblies can create conductive salts and metal filaments that cause shorts and premature failures, sometimes forcing full board replacement.

Altium and SVTronics both describe multiple corrosion mechanisms:

Atmospheric corrosion occurs when moist air reacts with exposed metal, forming oxides. These oxides are insulators and mechanically weak, so resistance increases and metal flakes away.

Electrolytic filamentation happens when a moisture film with dissolved electrolytes covers a metal surface while a voltage is present. Dendritic metal filaments grow along the surface, eventually bridging conductors and creating shorts.

Galvanic corrosion arises where dissimilar metals and dissolved salts coexist, even without an applied voltage. Over time, one metal preferentially corrodes.

Fretting corrosion occurs at contact interfaces such as plated switches. Repeated mechanical motion removes protective oxides; with moisture present, fresh metal oxidizes and the contact degrades.

Additional mechanisms occur inside the board. Cadence highlights conductive anodic filamentation, where conductive filaments grow inside the laminate between conductors. Technotronix and others point out that the standard fiberglass‑epoxy laminates are hygroscopic. The resin absorbs water, which lowers the glass transition temperature, promotes delamination, and changes dielectric behavior. That shift in dielectric constant and loss factor slows circuits and upsets controlled‑impedance lines.

In other words, moisture is not just a cosmetic problem. It alters surface conductivity, grows its own unintended conductors, and changes the properties of the laminate itself.

What Is A Conformal Coated PCB Module?

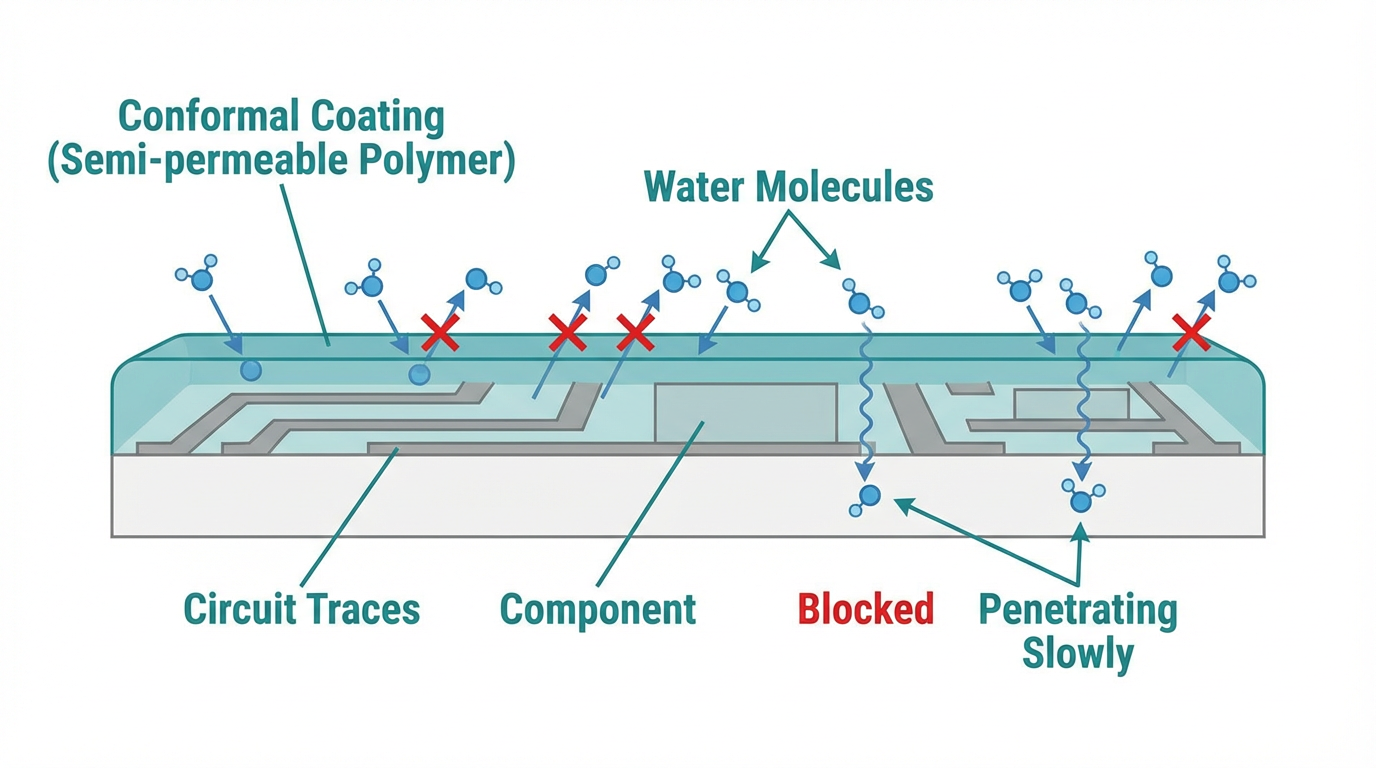

A conformal coating is a thin polymer film applied over a PCB assembly so that it conforms to the surface topography. PCB reliability articles describe typical coating thicknesses in the range of roughly 25 to 250 microns. In imperial terms, that is on the order of about 0.001 to 0.010 inches. At those thicknesses, the coating can cover solder joints, component leads, and traces while adding minimal weight and volume.

A conformal coated PCB module goes a step beyond a bare coated board. It is a functional assembly, usually on a carrier or frame, with connectors, mounting features, and a defined interface to the rest of the system. The working circuitry is conformally coated, while mating connectors, adjustment points, and test pads are masked off or otherwise kept free of coating.

This module-level approach is very attractive in industrial automation for several reasons.

The module supplier handles coating material selection, masking, and process control.

You receive a field‑replaceable unit that is already hardened against moisture and contaminants.

The mechanical and electrical interfaces stay clean and defined, while the vulnerable circuitry gains an extra barrier against condensation and airborne contamination.

As Techspray and other coating specialists emphasize, conformal coatings are not perfectly impermeable. They are semi‑permeable barriers that greatly slow moisture uptake and surface leakage, but they do not create a hermetic seal.

That is a critical distinction when you decide how to use them.

Where Coated Modules Shine In Industrial Automation

The research corpus is consistent on the kinds of environments that punish unprotected electronics: humid climates, marine air, washdown and food processing areas, corrosive industrial atmospheres, and any system that cycles temperature frequently.

LinkedIn and TwistedTraces both stress that in humid and marine settings, moisture can condense on traces and component bodies, accelerating electrochemical migration and corrosion. SoftCircles extends the perspective to entire installation sites, pointing to sectors such as energy, manufacturing, and telecom that depend on weatherproof enclosures, IP66‑class housings, and humidity control to keep equipment running.

In practice, conformal coated PCB modules are particularly useful when:

The cabinet or enclosure will live in a high‑humidity or coastal location, even if nominally indoors.

Washdown, spray, or cleaning cycles will throw water at the enclosure.

Condensation is likely on startup or shutdown, such as outdoor equipment, water industry assets, and unconditioned plant rooms.

The electronics service critical processes where corrosion‑driven failure is not acceptable between major overhauls.

In those situations, a coated module adds a cheap but effective layer to complement enclosures, gaskets, desiccants, and humidity control.

Failure Modes Conformal Coating Mitigates

Surface Leakage And Short Circuits

SVTronics explains that the most common immediate failure from water on a PCB is short‑circuiting. Water films and droplets form alternative conductive paths with lower resistance than the intended trace network. When that alternative path exists between two pins at different potentials, current diverts through the water, sometimes creating sparks and catastrophic failure.

Electronics design guidance on hot, moist environments points out that a sustained DC voltage gradient between nearby pins accelerates electrochemical reactions. A practical layout recommendation from designers is to avoid placing two adjacent pins where one is nearly always at a high DC potential and the other at ground. Where that is unavoidable, it is safer to separate them physically, rearrange pinouts, or operate signals at lower voltages.

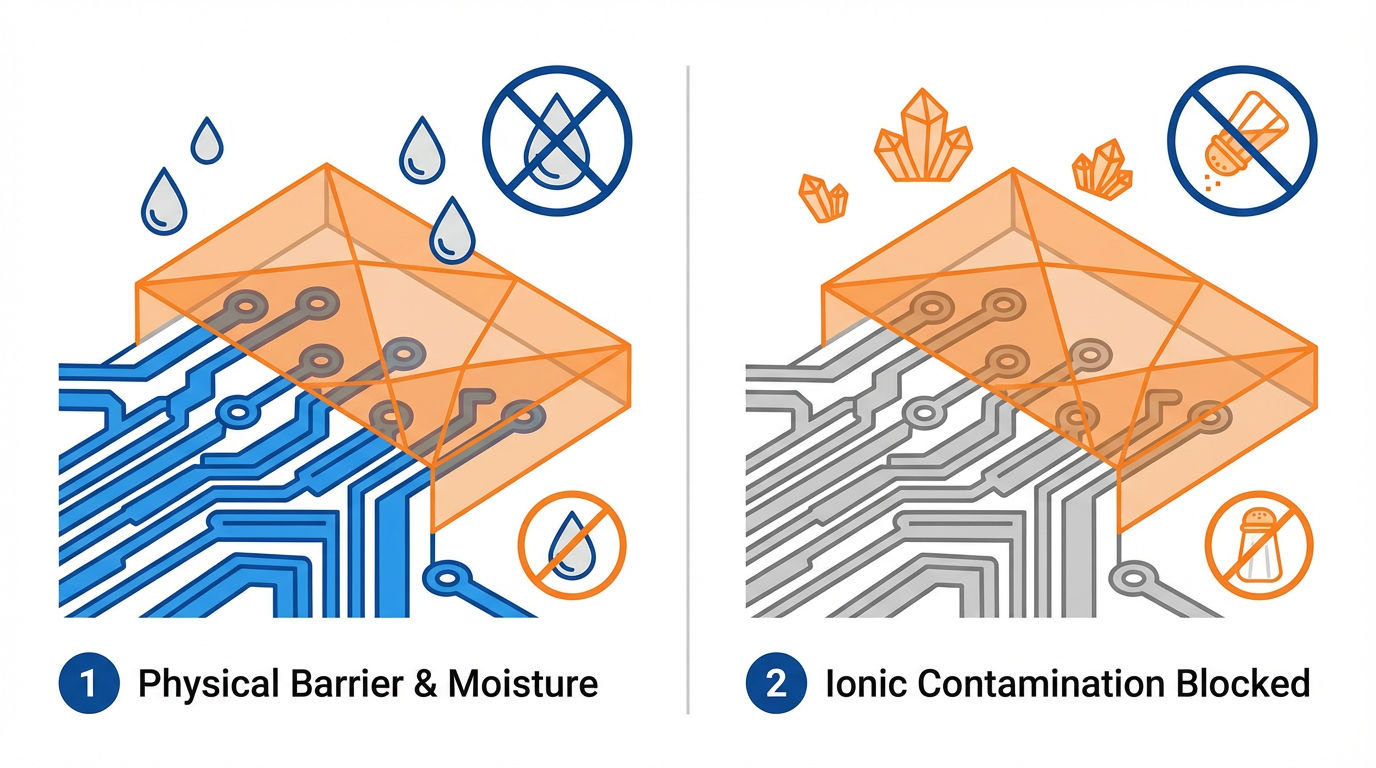

Conformal coating addresses surface leakage in two ways. First, it physically separates airborne moisture from conductors, so it is much harder for water films to form directly between exposed metals. Second, when properly applied and cured, it blocks or slows ionic contamination from reaching those surfaces, which dramatically reduces the conductivity of any moisture that does get through.

Cadence and Techspray both note that conformal coatings greatly reduce humidity‑driven growth of conductive salts and filaments on exposed metals, cutting down the surface leakage and shorts that would otherwise occur.

Corrosion And Electrochemical Migration

The corrosion mechanisms cataloged by Altium and SVTronics all require moisture plus reactive species such as oxygen, salts, or flux residues. Once those preconditions exist, metal ions move, oxides grow, and conductive dendrites creep across surfaces.

Conformal coating slows this process by:

Reducing access of oxygen and moisture to metal surfaces.

Encapsulating residues so they cannot dissolve easily into water films.

Providing a physical barrier that dendrites must penetrate or grow around.

However, coating is not a substitute for cleanliness. Several sources, including the moisture‑protection guidance from Sierra and Altium, stress that exposed metals must be thoroughly cleaned before plating and coating.

If aggressive residues remain under the coating, they can still react, especially if pinholes or incomplete coverage allow localized moisture ingress.

Inside The Laminate: CAF, Delamination, And Popcorning

Not all moisture problems occur on the surface. Cadence and Technotronix both emphasize that typical PCB base materials use a glass fiber weave impregnated with resin and curing agents, and that resin is hygroscopic.

If bare laminates or finished boards sit in high humidity without protection, they absorb water. That water:

Lowers the effective glass transition temperature, making the board more fragile at soldering temperatures.

Promotes conductive anodic filamentation between buried conductors.

Increases the risk of delamination and blistering during high‑temperature steps.

Altium and other manufacturing sources describe the classic “popcorning” failure in moisture‑sensitive components during reflow. Moisture absorbed into plastic packages vaporizes rapidly during soldering, cracking the package and damaging internal connections.

Conformal coating cannot reach into the laminate, so it does not eliminate these mechanisms. What it can do is significantly slow additional moisture ingress during field life, buying time between controlled drying at manufacture and the eventual accumulation of moisture in service.

Coating Technologies For PCB Modules

Main Families Of Conformal Coating

Different coating chemistries trade off ease of use, mechanical and chemical robustness, reworkability, and cost. A number of sources, including Altium, LinkedIn, Sierra, and Techspray, describe the mainstream options as follows.

| Coating type | Key properties | Typical industrial uses | Main limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylic | Good moisture protection, good dielectric properties, relatively easy to apply and remove; cures quickly | General industrial control, assemblies that may require field rework | Moderate temperature and chemical resistance; not ideal for the harshest environments |

| Silicone | Excellent moisture and chemical resistance, very flexible, wide temperature range, as described in multiple conformal coating guides | Electronics exposed to thermal cycling, vibration, and severe humidity; high‑humidity environments identified by Techspray’s silicone coatings | Difficult to remove for rework; may be incompatible with some test or inspection procedures |

| Urethane (polyurethane) | Strong abrasion and chemical protection, good moisture barrier, robust mechanical properties | Environments with chemical splash or mechanical wear, such as industrial machinery and transportation | Harder to apply uniformly and more difficult to rework than acrylics; overspecification can reduce serviceability |

| Epoxy | Hard, tough coating with very strong chemical and moisture resistance | Niche use where maximum durability is needed and rework is not expected | Brittle compared to silicones, and very difficult to remove once cured |

| Parylene | Vapor‑deposited, pinhole‑free, uniform coating; exceptional moisture and chemical resistance; biocompatible as noted in medical and harsh‑environment discussions | High‑reliability, high‑value modules in medical, aerospace, or mission‑critical industrial systems | Requires specialized equipment and processing; higher cost than liquid coatings |

Industry references such as IPC‑CC‑830 define performance requirements rather than prescribing specific chemistries. From a systems standpoint, the message is straightforward: match coating family to environment, serviceability expectations, and budget, not to marketing claims alone.

Conformal Coating Versus Potting, Overmolding, And Nano‑Treatments

Conformal coating sits alongside several other moisture‑protection strategies described by SVTronics, Caplinq, Techspray, and other sources.

| Method | Description | Strengths | Drawbacks and typical fit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conformal coating | Thin polymer layer over board and components, leaving connectors and defined areas uncoated | Light, preserves access for test and limited rework, effective against humidity and condensation, improves resistance to contaminants | Semi‑permeable; not a complete waterproofing; masking and rework add complexity |

| Potting | Full encapsulation of the assembly in a solid or gel‑like material such as epoxy or silicone | Excellent environmental and moisture protection, strong mechanical support, good for vibration and high‑voltage isolation, highlighted in Techspray’s potting guidance | Adds weight and volume, generally not reworkable, can trap moisture if the board is not dry first as SVTronics warns |

| Thermoplastic overmolding | Injection of molded plastic around parts of the assembly, leaving connectors exposed | Ruggedization, strain relief, partial moisture barrier for certain geometries | Requires tooling, not suited for dense mixed‑height assemblies; SVTronics reminds designers to keep connectors exposed |

| Microencapsulation / partial potting | Resin applied only to specific sensitive regions or components | Focused protection of high‑risk areas with less material and weight | Complex process definition; must avoid creating moisture traps |

| Nano‑coatings and waterproofing treatments | Very thin hydrophobic treatments such as the NanoProof series described by Caplinq, ranging from splash resistance to IPX7‑class immersion resistance | Minimal impact on weight and geometry, can be applied late in the process, some families reach immersion‑grade performance | Performance varies by product; some are aimed at consumer devices rather than industrial modules; long‑term industrial data may be limited |

For industrial control modules that must remain field‑replaceable and testable, conformal coating and carefully chosen nano‑treatments are usually preferable to full potting. Potting tends to make more sense for dedicated, non‑serviceable assemblies subjected to continuous immersion or extreme vibration.

Designing A Reliable Conformal Coated Module

Layout And Voltage Strategy

Protective coatings are far more effective when the underlying layout respects moisture‑driven physics.

Electronics practitioners who work in hot, moist environments point out that electrochemical corrosion is driven strongly by constant DC voltage gradients between nearby conductors. If one pin sits at a high DC level and the adjacent pin is usually at ground potential, any residual moisture and contamination will tend to grow conductive paths between them.

Practical design strategies include:

Choosing the lowest operating voltages that still meet system requirements, reducing the driving force for electrochemical migration.

Avoiding adjacent pin assignments with permanently different DC potentials where possible, or separating them with grounded guard pins.

Avoiding long parallel traces at different potentials in areas where condensation is likely, as the LinkedIn design guidance recommends.

Where signals are otherwise static, modulating or pulsing them rather than holding a constant DC level, provided the end application behavior remains unchanged.

On top of this, Altium and Sierra stress that surface platings such as ENIG, ENEPIG, and similar nickel‑gold finishes help slow corrosion on exposed copper, especially when combined with conformal coating.

Material Selection And Board Fabrication

Several sources emphasize that moisture management starts with laminate and fabrication choices, long before coating.

Cadence describes standard PCB materials as glass fiber weave plus hygroscopic resin. Technotronix explains that moisture enters through prepregs, wet processes, and microcracks. Both recommend storing materials in dry, humidity‑controlled environments and pre‑baking laminates at temperatures just above water’s boiling point, around 212 °F, to remove residual moisture.

Altium notes that proper storage and pre‑baking help prevent delamination and conductive filament growth between conductors inside the laminate. Technotronix adds process specifics such as using gloves when handling prepregs, limiting internal voids by maintaining appropriate vacuum levels during lamination, and baking silkscreen and solder mask properly to drive off moisture introduced by wet processes.

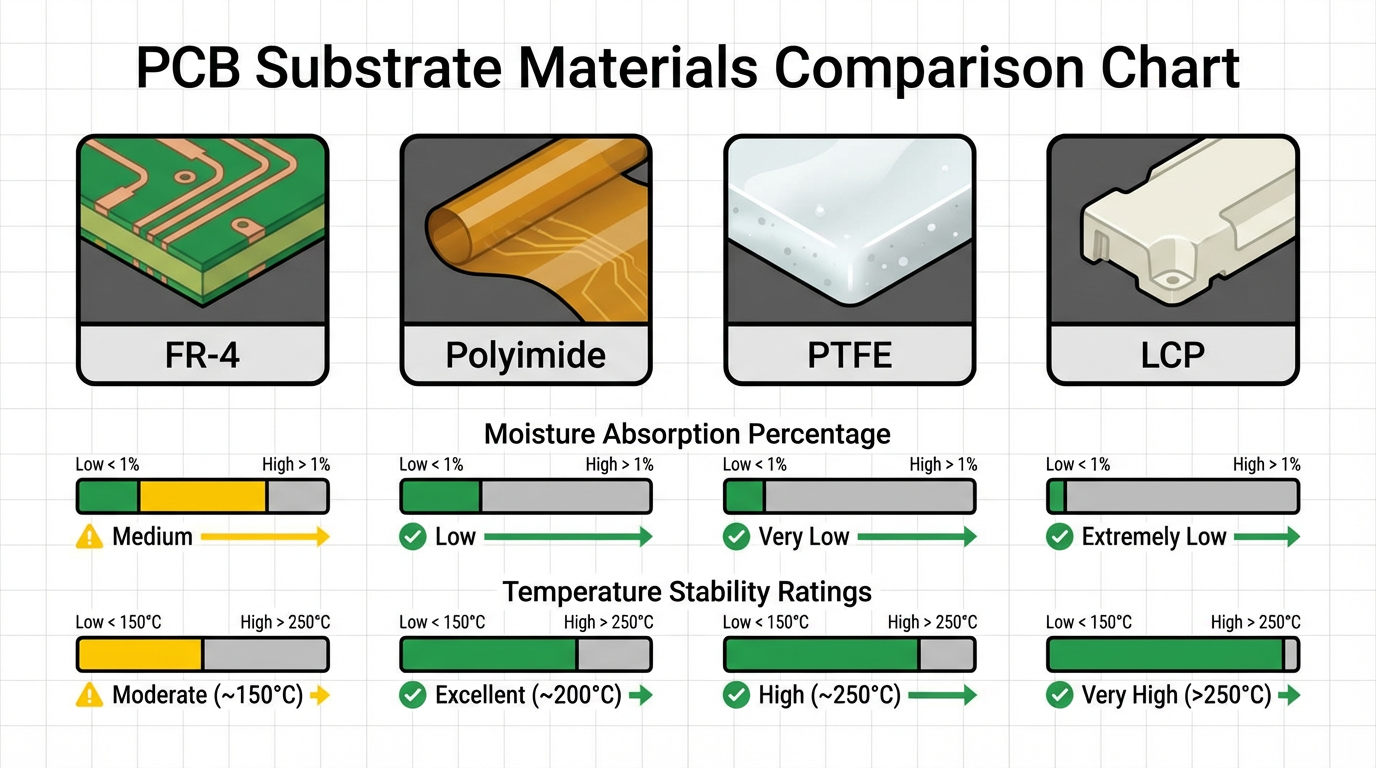

For harsh environments, LinkedIn and Sierra discuss moving beyond baseline FR‑4 to materials such as polyimide, PTFE‑based laminates, or liquid crystal polymer, which offer lower moisture absorption and better dimensional stability under humidity and temperature cycling.

Those changes are usually justified in high‑reliability modules where moisture is a primary risk.

Components, MSL, And Packaging

Moisture‑sensitive devices are covered by JEDEC moisture sensitivity level classifications. Altium’s summary of J‑STD‑020F describes eight MSL levels. At one end, MSL 1 components have unlimited floor life and can be exposed to ambient conditions indefinitely. Increasing MSL numbers bring progressively shorter maximum exposure times at typical assembly‑floor humidity. MSL 3, for example, allows about 168 hours out of dry pack, while MSL 5A allows only about 24 hours before baking becomes mandatory. MSL 6 parts must always be baked before use.

Articles from ICHOME, ACDI, and others agree on the practical handling:

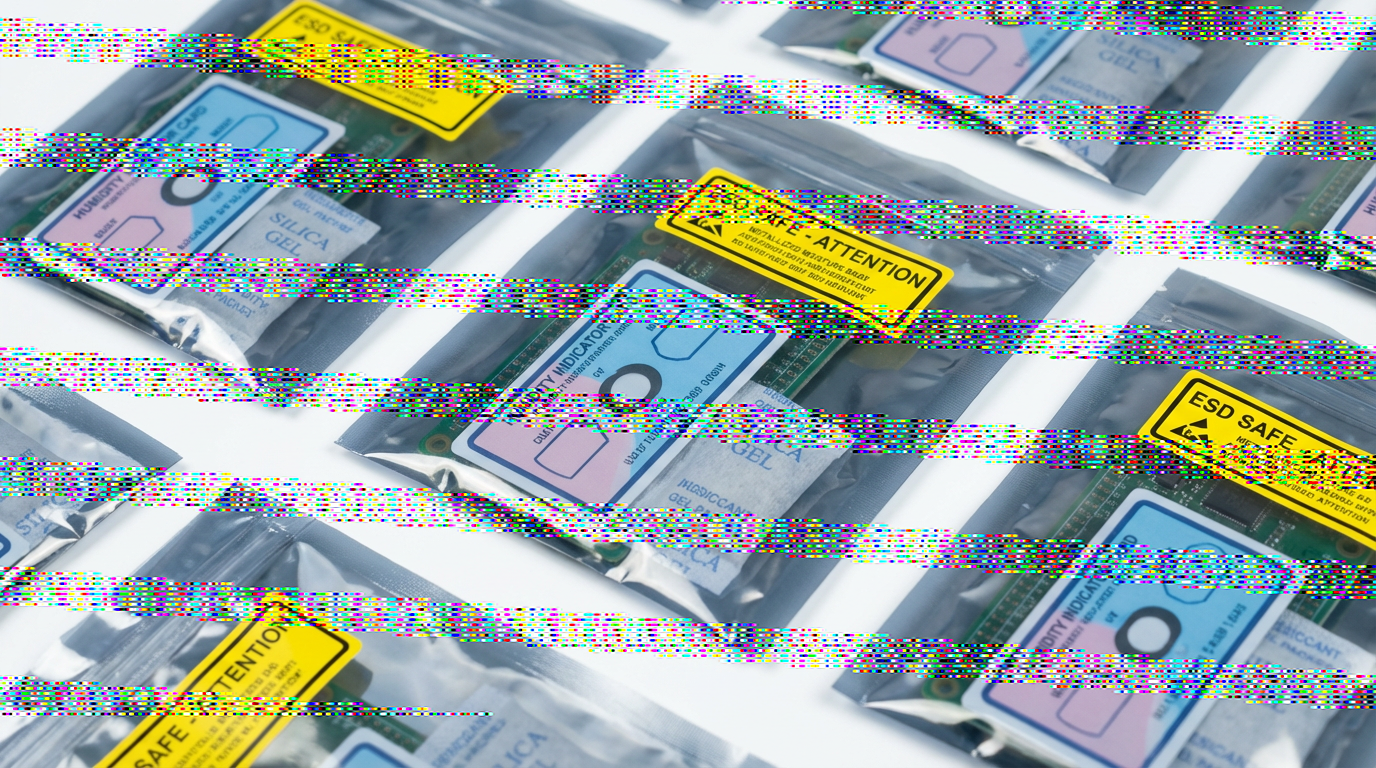

Store moisture‑sensitive components in sealed moisture barrier bags with desiccant and humidity indicator cards.

Use controlled‑humidity or dry cabinets for opened reels, often targeting very low relative humidity in the single‑digit percent range for long‑term storage.

Track exposure time on the factory floor carefully; if limits are exceeded, bake parts and sometimes boards at temperatures around 212 to 257 °F following component datasheet recommendations.

PCB‑Hero and related sources emphasize that both bare PCBs and components should be stored in ESD‑safe moisture barrier bags, not just ESD‑only packaging, to manage both electrostatic and moisture risks.

For conformal coated modules and their spares, it remains good practice to ship and store assemblies in moisture barrier packaging with silica gel and indicator cards, especially before first installation. SVTronics and Altium both point out that silica gel is only effective below about 140 °F. Above that, the equilibrium shifts, moisture desorbs, and the gel can release water back into the package. That is why shipping and storage instructions often include maximum temperature limits.

Making The Design Coating‑Friendly

Conformal coating is much easier to apply and maintain when the design anticipates it.

SoftCircles and SVTronics note that connectors, switches, and some adjustment devices must remain free of coating or overmolding. Masking these areas is standard practice, but heavy masking around densely packed interfaces is slow and error‑prone. In module‑level design, it helps to:

Cluster coating‑free interfaces such as connectors and mechanical switches where masking can be done efficiently.

Avoid tall components that shadow areas critical to creepage and clearance, which can leave uncoated “valleys.”

Provide test points that remain accessible even after coating, or specify removable or penetrable areas using softer materials such as certain silicones where needed.

Integrating Coated Modules Into Enclosures

A conformal coated module survives moisture better, but it cannot defeat a badly designed enclosure.

The Attabox guidance on condensation reminds designers that a perfectly sealed enclosure can still trap humid air, which condenses on cold surfaces when temperature drops. They recommend using designed breather and drain vents to equalize humidity and let accumulated moisture escape, rather than relying solely on sealing.

SoftCircles expands this view with best practices for harsh sites. Weatherproof enclosures made from durable materials such as polycarbonate or stainless steel, combined with correctly rated gaskets and mechanical locks, form the primary barrier against rain, snow, and spray. Polycarbonate enclosures, as Attabox notes, also have lower thermal conductivity than metals such as aluminum or copper, which helps slow internal temperature swings and reduces cold spots where condensation prefers to form. Polycarbonate is also non‑conductive, which is valuable where water may contact the enclosure itself.

IP and NEMA ratings provide an objective way to match enclosure performance to moisture risks. Altium explains that IEC 60529 uses a two‑digit code in the form IPXY, where the first digit describes solid debris protection and the second digit describes liquid protection. As their table shows, mid‑range ratings such as IP65 and IP66 provide strong dust protection and resistance to water jets, while higher moisture digits such as 7 and 8 correspond to immersion tolerances for specific depths and durations. TwistedTraces and Caplinq discuss IP68‑class designs aimed at continuous immersion beyond about 3 ft of water. For industrial control modules, IP66 or better is typical when direct spray or washdown is expected, with higher ratings chosen where immersion or flooding is realistic.

SoftCircles, Rocksolid, and EE Times all emphasize that environmental control inside the building matters as much as enclosure selection. Maintaining relative humidity roughly in the 40 to 60 percent range in electronics manufacturing and control spaces reduces both electrostatic discharge risks at low humidity and corrosion risks at very high humidity. Where ambient conditions do not cooperate, dehumidifiers, HVAC‑integrated humidity control, and localized conditioning in panel rooms and shelters become necessary elements alongside conformal coated modules.

Manufacturing, Coating, And Handling: Avoid Trapping Moisture Inside

Coating will not save a board that is already saturated with moisture. Several sources emphasize that point.

SVTronics points out that potting can trap water inside if the PCB is not dry before encapsulation. The same logic applies to conformal coating. Cadence and Technotronix recommend pre‑baking bare laminates and sometimes fully assembled boards at controlled temperatures just above water’s boiling point to drive out moisture before sealing them up.

Within assembly, Altium notes that component and board baking around 212 to 257 °F is used to reset moisture sensitivity levels when exposure limits are exceeded. ACDI and similar manufacturing guides describe using temperature‑humidity‑bias and related environmental tests at elevated temperature and relative humidity, such as around 185 °F at high relative humidity, to screen designs for moisture robustness before volume production.

Once conformal coating is applied, full curing is critical. Altium remarks that porous or incompletely cured coatings leave paths for moisture ingress and give a false sense of security. In practice, that means:

Following the coating supplier’s cure schedule faithfully.

Avoiding shortcuts where coated boards are packed or powered before cure is complete.

Verifying coverage, especially around component leads, sharp edges, and standoffs where surface tension can pull coatings thin.

On the logistics side, storage recommendations from ICHOME, Rocksolid, and TwistedTraces are aligned. Keep spares in dry, temperature‑controlled rooms, use moisture barrier bags with fresh desiccant for long‑term storage, avoid moisture‑prone locations such as bathrooms, damp basements, and unventilated closets, and consider periodic inspections and power‑ups so that internal self‑heating can help dry any trace moisture before it accumulates.

Is A Conformal Coated Module Enough?

Conformal coated PCB modules are powerful tools in the moisture‑protection stack, but they are one layer, not the entire solution. Techspray’s comparison between conformal coating and potting, Caplinq’s waterproofing treatments, and multiple enclosure articles all lead to the same conclusion.

Coating is usually enough when:

The environment is humid but not immersion‑grade, such as standard plant rooms, sheltered but not conditioned spaces, and cabinets that may see occasional condensation.

Enclosures and cable entries are well designed, with appropriate IP ratings, gaskets, and sealed glands.

You value serviceability, diagnostics, and the ability to rework or swap modules.

Coating alone is risky when:

Modules may see standing water, continuous spray, or immersion, as in some outdoor or marine installations, unless enclosure design fully prevents ingress.

The environment contains aggressive chemicals or pollutants beyond water and common industrial atmospheres.

You cannot guarantee controlled storage, handling, or enclosure integrity over the service life.

In those harsher cases, combining conformal coated modules with high‑grade enclosures, potting of the most exposed subassemblies, and in some cases advanced waterproofing treatments makes more sense.

The point from a systems integration perspective is to decide consciously where you want the moisture barrier to “stop.” You can stop it at the room via humidity control, at the enclosure via IP‑rated housings and good sealing, at the module via conformal coating, or at the component via potting. Most robust designs use a combination, with conformal coated PCB modules at the heart.

Brief FAQ

Does conformal coating make a PCB module waterproof?

Industry sources such as Techspray and Caplinq are clear that conformal coatings are semi‑permeable. They dramatically reduce moisture‑driven leakage and corrosion under humidity and occasional condensation, but they do not provide the same level of protection as full potting or a hermetic enclosure. For applications that expect continuous immersion or standing water, conformal coating must be combined with high‑grade enclosures, and sometimes potting, to reach true waterproof performance.

Can conformal coated modules be reworked or repaired?

Altium’s discussion of acrylic and other coatings notes that some chemistries are relatively easy to strip, while others, especially silicones, urethanes, and epoxies, are much harder to remove. LinkedIn’s analysis acknowledges that coatings complicate rework because coating must be removed and then reapplied. In practice, you can plan for limited rework on coated modules, but repeated deep repairs are impractical. Selecting more rework‑friendly coatings for modules that are likely to be serviced is often worth the trade‑off against maximum robustness.

How thick should a conformal coating be on an industrial module?

PCB reliability sources define conformal coatings as thin polymer layers in the range of roughly 25 to 250 microns, which is about 0.001 to 0.010 inches. That range is thick enough to form a continuous barrier over solder joints and leads while thin enough to preserve clearances and minimize added stress. The precise value depends on chemistry, application method, and the coating supplier’s specification, but industrial modules typically live within that band.

A conformal coated PCB module is not a magic shield, but when it is specified intelligently, built on sound materials and layout, and integrated into a well‑designed enclosure and humidity‑control strategy, it turns moisture from a constant headache into a manageable engineering parameter. That is exactly the kind of layered, field‑proven protection that long‑lived industrial automation projects depend on.

References

- https://nrf.aux.eng.ufl.edu/_files/documents/14385.pdf

- https://www.electronics.org/system/files/technical_resource/E6%26S01_01.pdf

- https://www.rocksolidstorage.net/blog/storing-electronics

- https://www.caplinq.com/pcb-waterproofing-treatments.html

- https://www.techspray.com/the-essential-guide-to-waterproofing-electronics?srsltid=AfmBOopmyedF1KOZz4wO0maswRza0yoeXGf8_gwh7VhOl0ntljwgPV5l

- https://www.acdi.com/managing-moisture-in-electronics-manufacturing-best-practices-for-assembly-rework-and-long-term-reliability/

- https://resources.altium.com/p/circuit-design-tips-pcb-moisture-protection-humid-environments

- https://attabox.com/blogs/how-prevent-condensation-electrical-enclosures

- https://resources.pcb.cadence.com/blog/how-to-protect-a-circuit-board-from-moisture

- https://www.eetimes.com/humidity-control-best-practices-for-electronics-manufacturing/

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment