-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Allen-Bradley PowerFlex 525 Drive Availability: Current Stock and Ordering Information

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

Why PowerFlex 525 Availability Deserves Its Own Conversation

When a production line goes down because a single drive has failed, nobody in the room cares that the replacement was “only” a few hundred dollars. What matters is how long it takes to get the line back. In many plants, unplanned downtime runs into thousands of dollars per hour, a point echoed in spare parts guidance from Industrial Automation Co. The Allen‑Bradley PowerFlex 525 has become a workhorse variable frequency drive across manufacturing, material handling, and HVAC, so its availability is a direct lever on plant risk.

From the perspective of a systems integrator who has swapped more VFDs under pressure than I care to count, the PowerFlex 525 sits in an interesting spot. It is a current, in‑production family with broad distribution, but it is also networked, parameter‑dense, and tightly integrated into modern control systems. Hardware availability is usually good. Fast, low‑risk replacement depends just as much on how you handle catalog numbers, firmware, configuration backups, and your spare parts strategy.

This article pulls together what current technical sources say about the PowerFlex 525 and combines that with practical field experience to answer a simple question: can you rely on the market to supply these drives when you need them, or should you be keeping them on the shelf?

What the PowerFlex 525 Is (and Why It Is Everywhere)

The PowerFlex 525 is part of Rockwell Automation’s PowerFlex 520‑Series of adjustable frequency AC drives. As the Rockwell user manual explains, drives in this family convert fixed‑frequency AC into variable‑frequency, variable‑voltage output so they can precisely control motor speed, acceleration, deceleration, and torque. In practice, you see these units on conveyors, pumps, fans, blowers, and countless OEM machines where you need solid speed control and compact hardware more than exotic closed‑loop torque control.

Industrial Automation Co. and other engineering guides describe the PowerFlex 525 as a compact, configurable VFD with built‑in EtherNet/IP on many models, capable of controlling three‑phase induction motors and, in selected versions, permanent‑magnet motors. Across the 520‑Series, input voltage coverage spans roughly 100 to 600 V AC, with both single‑phase and three‑phase options depending on catalog number. Power ratings range from fractional horsepower up to roughly 30 hp, with the PowerFlex 525 family covering most small to mid‑sized industrial applications.

From the PDFSupply overview, you see how broad this family is. There are 200 to 240 V three‑phase models, such as 25B‑B017N104 and 25B‑B032N104, and 380 to 480 V three‑phase models such as 25B‑D010N114, 25B‑D030N114, and 25B‑D037N114. There are also “V” models like 25B‑V4P8N104 and 25B‑V6P0N104 that take 100 to 120 V single‑phase in and provide three‑phase motor output, which is very useful where only low‑voltage single‑phase power is available in the field.

A specific example helps anchor the discussion. The 25B‑D2P3N104, documented by PDFSupply, is a 380 to 480 V AC model rated around 1 hp at 2.3 A. It supports multiple control modes, including volts‑per‑hertz, several flavors of sensorless vector control, and permanent‑magnet motor control. It has a detachable power module and control module to simplify installation and replacement, and it includes embedded EtherNet/IP plus a DSI serial interface. That combination of mechanical flexibility, modern networks, and broad motor compatibility is typical for the family and is precisely why the 525 shows up in so many panels.

Rockwell’s own case study on the Drake LS‑600R sausage autoloader is a good illustration. That machine uses PowerFlex 525 drives on its infeed and discharge conveyors, controlled over EtherNet/IP from a CompactLogix controller. When you pick a drive like this as the default conveyor drive in a high‑speed food packaging machine, you are implicitly betting that it will be available and supportable for years.

In‑Production vs. Obsolete: Where the 525 Sits in the Lifecycle

Spare parts strategy guidance from Industrial Automation Co. draws a sharp contrast between obsolete drives such as the Allen‑Bradley 1336 PLUS II and in‑production drives such as the PowerFlex 525. Obsolete families tend to have limited remaining stock and long lead times; the example given is an eight‑week lead‑time legacy drive that controls a bottleneck production line. Those are the kinds of parts you absolutely must stock if the process is critical.

By comparison, the same guidance calls out the PowerFlex 525 as a modern, widely available drive line. Because these drives are still in active production and widely used, the recommendation is often to monitor their availability rather than automatically stocking them heavily. That is consistent with what we see in the field: the 525 is part of Rockwell’s current portfolio, widely deployed, and still featured in modernization and migration literature, such as the Rexel USA discussion on moving from PowerFlex 40 to PowerFlex 525.

The migration note from Rexel USA underlines another reality. Both the PowerFlex 40 and 525 are essentially volts‑per‑hertz drives with a sensorless vector mode that can boost current to maintain speed under load, but they do not provide true torque regulation. For torque‑following applications, Rockwell points integrators toward the 750‑Series (PowerFlex 753/755). That matters for availability because it reinforces the role of the 525 as a general‑purpose, mid‑range workhorse. These are exactly the drives that high‑volume distributors tend to support with stock, while more niche high‑end units often run on longer lead times.

Signals From the Market: Who Stocks PowerFlex 525 Drives

You never see a single global “in stock” flag for a drive family, but the way different technical sources talk about the PowerFlex 525 is telling.

In their engineer‑focused setup guide, Industrial Automation Co. explicitly notes that they stock a full range of PowerFlex 525 drives for quick replacement or new builds. In practice, that means you can treat them as a stocking distributor for common 525 variants, which is valuable when you are designing around availability.

The PDFSupply catalog information shows a deep lineup of specific PowerFlex 525 catalog numbers at both 200 to 240 V and 380 to 480 V, plus accessories such as the 25‑COMM‑D DeviceNet adapter. They highlight features like embedded EtherNet/IP on many N114 models and emphasize that the 525 family is suitable for applications ranging from fans and pumps to conveyors and machine tools. The breadth of part numbers they cover is a practical indicator that these drives are actively traded in the market rather than rare specials.

On the repair and surplus side, Radwell documents repair service for at least one specific PowerFlex 525 model (25B‑D2P3N104), with an estimated repair price and a typical evaluation workflow. That is another availability signal: when independent repair houses build repeatable repair offerings around a drive family, it usually means there is a large enough installed base to justify the effort, and that the parts are not on the verge of disappearing.

You also see the PowerFlex 525 show up in technical tutorials from independent engineering sites such as SolisPLC and One Motion. Those sources focus on integrating the drive over EtherNet/IP into Studio 5000 projects and on setting static IP addresses through parameters C128 to C136. You do not invest in that level of documentation for hardware that is hard to come by; you do it for the drives that are in many cabinets and likely to be around for a while.

Taken together, these signals line up: the PowerFlex 525 is a current, actively supported drive family with broad distributor coverage and an ecosystem of support, repair, and application content around it.

How Stock Levels Tie Into a Smart Spare Parts Strategy

Drive availability is not just about what distributors claim to stock today. It is about how you design your own inventory strategy so one failed drive does not dictate your production schedule.

Industrial Automation Co.’s “smart spare parts strategy” guidance describes a simple but rigorous approach. First, you classify equipment and rank assets by criticality, failure history, and replacement lead time. Drives, PLCs, and communication modules often land in the high‑risk category because they can shut down an entire line. High‑risk examples include bottleneck assets with long lead times, such as a legacy drive with an eight‑week wait, while modern devices that can be replaced next day sit at the other end of the spectrum.

Second, you identify genuinely critical spares. Those are parts with long or unpredictable lead times, obsolete or discontinued product lines, high downtime impact, or exposure to tariffs and import delays. In many plants, these critical spares include older drive families, unique PLC CPUs, and specialized communication modules.

Third, you balance stocking versus sourcing. For each part, you look at what happens if it fails, how long a replacement takes, and whether repair is a viable, fast option. The same guidance notes that if repair turnaround is quick, stocking may be unnecessary; but if failure would shut a line for weeks, you should hold at least one spare.

When you apply that logic to the PowerFlex 525, you end up with a nuanced picture. For many non‑bottleneck applications, the combination of broad distributor availability and repair options means you can plan to source replacements or repairs as needed, especially if your plant is in a region with good logistics. For a small number of critical assets, especially where a PowerFlex 525 is driving a bottleneck machine or you face longer logistics times, holding one or two spares is still cheap insurance compared with the cost of extended downtime.

The key is that the PowerFlex 525, unlike obsolete legacy drives, rarely forces you to tie up capital in a large stockpile “just in case.” Its position as an in‑production, widely used family lets you be more selective and data‑driven.

Pros and Cons of Relying on Market Availability

Relying on distributor stock for the PowerFlex 525 has clear advantages. You avoid tying up capital in shelves of identical drives that may never be used. You reduce the risk of your own spares aging out or being superseded. You also benefit from ongoing improvements, such as incremental firmware updates or design revisions, by buying current‑production units when you need them.

The downside is that you are betting on someone else’s inventory and on the reliability of your supply chain. Even for an in‑production drive, regional disruptions, tariff changes, or short‑term demand spikes can stretch lead times. The spare parts strategy guidance explicitly points out that exposure to tariffs and import delays is a factor in deciding whether to stock a part. If your plant is in a region where imports of industrial controls have already seen unpredictable delays, you should treat market availability less generously in your risk calculations.

Another subtle drawback is configuration effort. A replacement PowerFlex 525 is not a drop‑in part until it has the right parameters, network settings, and safety options configured. That configuration time is a meaningful part of your downtime. The more complex the application, the more incentive you have to keep at least one fully compatible spare on the shelf, pre‑configured or ready to accept a known parameter set, so you are not rebuilding from scratch at three in the morning.

In short, the PowerFlex 525’s strong market availability shifts the conversation from “Do we have to stock this?” toward “Where is it safe not to stock this, and where does the risk still justify a physical spare?” That is a better position to be in, but it does not remove the need to think.

Ordering a PowerFlex 525: Getting the Catalog Number Right

When you do order a PowerFlex 525, the first job is to make sure you are asking for the right catalog number. Rockwell and distributor literature is very clear that you must match the drive’s voltage and rating to the application, and many start‑up issues trace back to mismatched catalog numbers or incorrect wiring.

From the PowerFlex 520‑Series user manual and Industrial Automation Co. quick‑start notes, a few practical checks stand out. Verify the input voltage class and motor horsepower rating, whether you are in the roughly 200 to 240 V range, the 380 to 480 V range, or using low‑voltage single‑phase “V” models that take around 100 to 120 V in. Confirm whether your application needs single‑phase input capability, because not all models support it. Check the ambient temperature and mounting conditions; for full ratings, the drives are designed to operate up to about 122°F in the proper enclosure and orientation, with specified top and bottom clearances for cooling.

Mechanically, the PowerFlex 525 is a compact IP20 open‑type drive intended for vertical mounting on DIN rail or a panel backplate. For higher ambient temperatures or at altitude, Rockwell literature notes derating requirements. Horizontal mounting is supported on some models when you add a cooling fan. From an availability perspective, that means you want to standardize on catalog numbers that fit your environmental envelope, rather than relying on marginal conditions where you might need a special enclosure or additional cooling hardware.

Electrically, ensure that the drive’s input current rating and motor current rating match your motor and protection scheme. Drives in this family are designed to work with proper branch circuit protection and grounding as described in the Rockwell manual and Industrial Automation Co.’s wiring guidance. Skipping those checks to grab “any 5 hp 480 V drive” from a reseller’s stock is how you end up with nuisance trips or premature failures.

Finally, do not forget options. Some PowerFlex 525 models include Safe Torque Off (STO), embedded EtherNet/IP with Device Level Ring support, or integrated EMC filtering; others rely on external modules or filters. PDFSupply’s catalog makes this clear, calling out which models include STO or IGBT braking and which include embedded Ethernet. If your existing application relies on a built‑in safety function or on a specific network interface, make sure the replacement drive’s catalog number matches that feature set, not just the horsepower.

Configuration and Networking: Availability’s Hidden Partner

The availability of a PowerFlex 525 on a shelf does not automatically translate into fast recovery. Modern drives carry a lot of configuration: motor nameplate data, acceleration and deceleration times, minimum and maximum frequency limits, overload settings, network addresses, and sometimes safety and braking configuration. If you do not have that configuration backed up, the downtime cost of rebuilding it can rival the delay of waiting for a drive to ship.

Engineer‑oriented guides from Industrial Automation Co. and SolisPLC both stress parameter backup and documentation. They recommend recording motor nameplate data, catalog numbers, firmware revisions, and key parameters such as motor voltage (P031), motor frequency (P032), overload current (P033), and motor speed (P034). They also advocate backing up complete parameter sets to Connected Components Workbench (CCW) or to a USB device, and keeping a configuration sheet in the panel.

The Rexel USA modernization note goes a step further when discussing migrating from PowerFlex 40 to PowerFlex 525. It strongly recommends using CCW early to upload and back up existing parameter sets before any drive fails, noting that you cannot retrieve parameters from a failed drive and that the 525 keypad does not have a simple “copycat” function for cloning configurations. Remote HIM modules can help, but software backups are more flexible.

On the Ethernet side, the One Motion troubleshooting guide on PowerFlex 525 network setup underlines how network configuration affects recoverability. To use EtherNet/IP reliably, you typically assign a static IPv4 address by setting parameter C128 to static mode and then entering the IP address and subnet mask through parameters C129 to C136. A full power cycle is required for the new settings to take effect, and you should always verify that the values stick after power‑up. If you replace a drive and forget to apply or confirm these network settings, the drive may be physically available but invisible to your PLC or diagnostic tools.

For plants that rely on networked drives, a realistic availability plan includes not just the hardware but also a configuration management process. That means having CCW or Studio 5000 projects with drive Add‑On Profiles, keeping parameter backups, documenting IP addresses, and ensuring someone on shift knows how to push a configuration to a new drive. Without that, your “in‑stock” PowerFlex 525 behaves like an unfamiliar spare, and the clock keeps ticking while you re‑discover how the last engineer configured it.

Repair vs. Replace: Using Repair to Reduce Stock

High‑volume drive families like the PowerFlex 525 benefit from an active repair ecosystem. Radwell’s offering for the 25B‑D2P3N104 is a concrete example. They invite customers to send in failed drives for evaluation by certified technicians, typically providing a detailed repair quote within about twenty‑four hours. The listed repair service carries an estimated unit price around a few hundred dollars, with the caveat that the final cost depends on what the evaluation finds, and no work proceeds without customer approval.

From a spare parts strategy standpoint, this underscores a point made in Industrial Automation Co.’s guidance: if repair turnaround is fast and reliable, you can lean more on repair and less on deep stocking for certain parts. For non‑critical applications, or where you have some level of redundancy, it may be acceptable to ship a failed PowerFlex 525 out for repair and run on remaining equipment, especially if the alternative is tying up capital in multiple identical spares.

The trade‑off is risk tolerance. Repair assumes that one drive can be out of service for days without hurting production; outright replacement assumes downtime must be minimized at almost any cost. For a PowerFlex 525 driving an auxiliary pump, repair may be a perfectly reasonable path. For a PowerFlex 525 that feeds a flagship packaging line like the Drake LS‑600R, most plants would rather keep a spare on the shelf and send the failed unit out later. The important thing is to make the decision consciously, using availability, repair lead time, and downtime cost as inputs, not guesses.

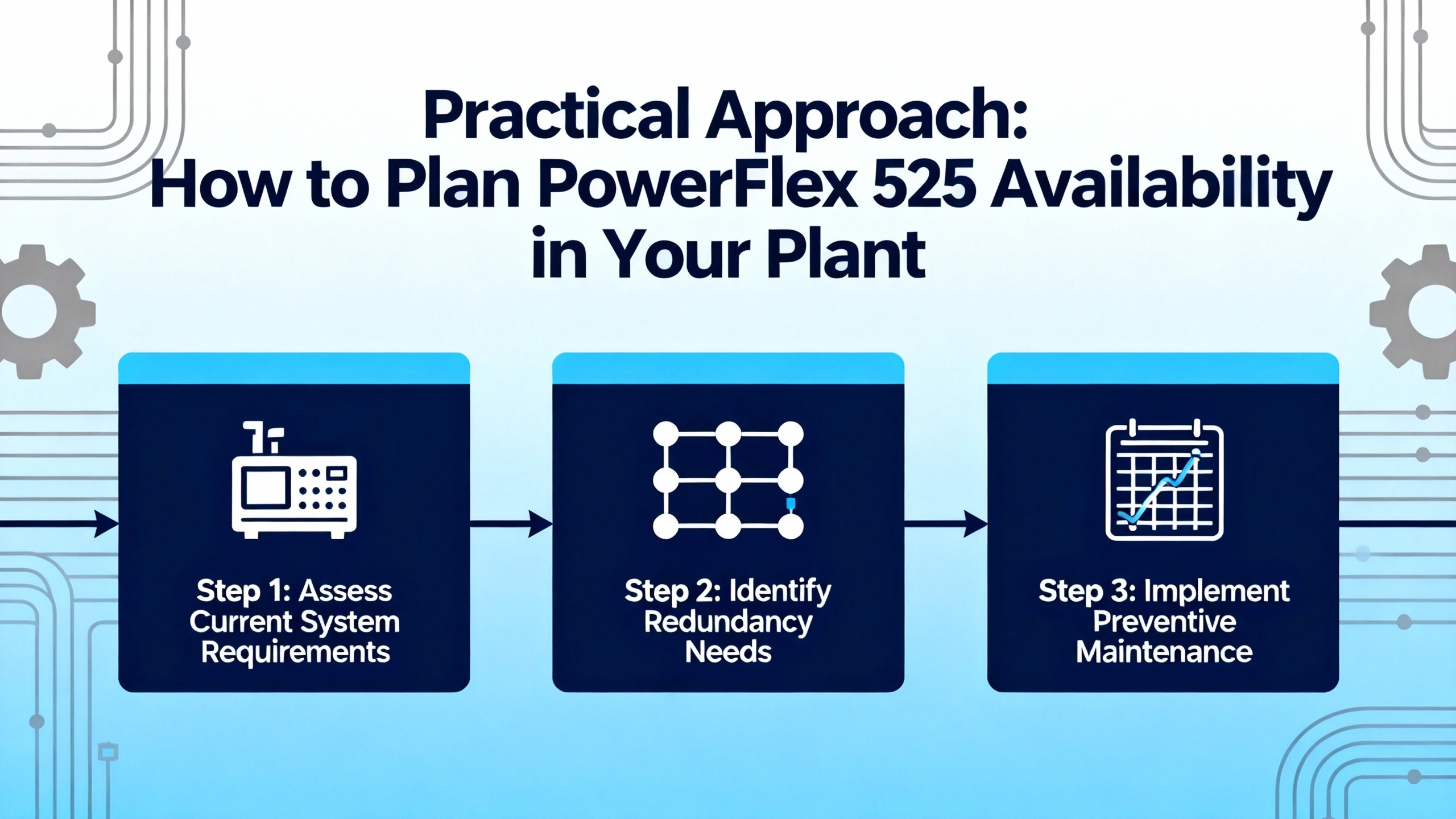

Practical Approach: How to Plan PowerFlex 525 Availability in Your Plant

In day‑to‑day project work, I treat the PowerFlex 525 as a generally available, current‑production drive with a few caveats. The first step is always to inventory the installed base. List which machines use the 525, what catalog numbers are present, and which ones sit on bottleneck equipment. Record the role of each drive: is it running a line‑critical conveyor, a non‑critical fan, or a redundant pump? That classification gives you the context you need for stocking decisions.

Next, for each distinct catalog number, consider the three factors highlighted in the spare parts strategy guidance: the impact of failure, the likely replacement lead time in your region, and the availability of fast repair. Where a failure would shut down a high‑value line and you cannot rely on same‑week delivery because of shipping constraints or tariffs, a spare PowerFlex 525 is cheap insurance. Where the drive is non‑critical and you have reliable access to distributors and repair houses, you can often rely on external availability and keep capital free for more fragile or obsolete parts.

Finally, keep the list moving. The same guidance recommends reviewing spare parts lists every six to twelve months. As you add new machines, retire old ones, or hear about product lifecycle changes from Rockwell or your distributors, adjust. The PowerFlex 525 is a current, healthy family today, but some of the 1336 drives in your plant looked that way once too. Keeping an eye on modernization notices and distributor lead times lets you shift from a “monitor and source” posture to a “stock spares” posture well before the supply dries up.

Brief FAQ on PowerFlex 525 Availability

Q: Do I need to stock spare PowerFlex 525 drives, or can I rely on distributors? A: For many applications, you can safely lean on distributor stock and repair services, because the PowerFlex 525 is an in‑production, widely available drive family. You should still stock spares for catalog numbers that sit on bottleneck equipment or are exposed to long or uncertain replacement and repair lead times in your region.

Q: How many spare PowerFlex 525 units should I keep? A: There is no universal number. Use the approach outlined by Industrial Automation Co.: look at what happens if a particular drive fails, how long a replacement or repair will realistically take, and what unplanned downtime costs your plant. If a failure would idle a high‑value line for weeks because of lead times, at least one spare of that catalog number is justified.

Q: What should I have ready before a PowerFlex 525 fails? A: Beyond any physical spares, have a clean inventory of catalog numbers, motor nameplate data, parameter backups through CCW or Studio 5000, and documented IP addresses and control sources. That preparation turns the good hardware availability of the PowerFlex 525 into genuinely fast, low‑risk replacement when something goes wrong.

In the end, the PowerFlex 525 has earned its spot as a reliable, widely stocked workhorse. Treat its availability as an asset, but do not let that lull you into complacency. A little structure around catalog numbers, configuration backups, and critical‑spare decisions will keep you on the right side of the downtime curve when the next drive fails at an inconvenient hour.

References

- https://resources.onemotion.tech/setup-troubleshooting-powerflex.html

- https://www.asteamtechno.com/how-to-set-up-and-program-your-allen-bradley-powerflex-525-vfd-a-complete-guide/?srsltid=AfmBOop15tkLkqwH-7FIJ0UO1Wd6jWHndPHOypS5rQ7pEIBPVwpYCyt0

- https://www.solisplc.com/tutorials/powerflex-525

- https://industrialautomationco.com/blogs/news/allen-bradley-powerflex-525-quick-start-installation-wiring-and-setup-guide?srsltid=AfmBOoogLZgcnA4ibztpgaqAUWSOgbolp1Ckf4W4YzRUlvlBLY8nPiwR

- https://www.pdfsupply.com/automation/allen-bradley/powerflex-525?srsltid=AfmBOooEd05_9EPN9GrUSsXDhOeXM6fKgVjOQUzWKSkFNWEFZbE_DeqF

- https://pages.rexelusa.com/blog/automation/drive-modernization-part-vi-powerflex-40-to-powerflex-525

- https://www.dosupply.com/automation/allen-bradley-drives/powerflex-525/25B-D2P3N104?srsltid=AfmBOoo59iFecdX_DB7-vh8ZY_sUJTubD0qsj43wYd9ymKDMTCEgmtjw

- https://www.radwell.com/Buy/ALLEN%20BRADLEY/ALLEN%20BRADLEY/25B-D2P3N104?srsltid=AfmBOoqbx2mXahs1_jisjYJcILLjWY9kxlVZKAQ-4KpXVEp0tttRfQW3

- https://www.circerb.chaire.ulaval.ca/Textbook/09rbDR/897468/Powerflex-525-User-Manual.pdf

- https://www.gevernova.com/power-conversion/sites/default/files/2021-12/GEA34072_BCH_Power%20Conversion%20Product%20and%20Solution%20Portfolio_EN_20191028.pdf

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment