-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Authorized Distributor Verification for Industrial Parts: A Practitioner's Guide

Industrial automation projects rarely fail because a PLC could not add two numbers. They fail because the wrong hardware showed up, someone bought “too good to be true” parts from a questionable source, or a critical component turned out to be counterfeit halfway through commissioning. As a systems integrator, I have seen more risk created at the purchase order stage than at any wiring diagram or PLC program.

Authorized distributors are supposed to be the antidote to that risk. But simply seeing the word “authorized” on a website or quote is not enough. In practice, you need a disciplined verification process that separates genuine authorized distribution from gray‑market trading dressed up with logos.

This article lays out a practical, field-tested approach to verifying authorized distributors for industrial parts, drawing on guidance from electronics industry practitioners, counterfeit‑avoidance communities such as ERAI, industrial supplier evaluation advice from Ever Trust Tools and 889 Global Solutions, and modern supplier‑intelligence perspectives from Veridion and Z2Data, along with regulatory analogs in highly controlled sectors like FDA‑regulated supply chains. The focus is industrial automation and control hardware, but the principles apply across mechanical, electrical, and electronic components.

Why Authorized Distributor Status Matters So Much

In the electronics world, purchasing professionals often distinguish between three tiers of supply: the factory (the original component manufacturer), franchised or authorized distributors that have formal agreements with that manufacturer, and everyone else, which includes independent brokers, excess‑inventory dealers, other contract manufacturers, and online marketplaces. Practitioners on technical forums point out that when you buy directly from the factory or from large franchised distributors, the risk of counterfeit parts is very low, because these channels stake their reputation on genuine supply and maintain direct relationships with the manufacturer.

Industrial automation and control hardware behaves the same way. The PLC, drive, or safety relay you buy carries not only its functional role, but also warranty obligations, safety certifications, and, increasingly, cybersecurity expectations. If you buy from an unauthorized channel, you may lose your warranty, lose recourse if the parts are fake, and introduce hidden safety and availability risks into your plant.

Communities that track counterfeit electronics, such as ERAI, repeatedly highlight cases where companies sourced “bargain” parts from brokers or online marketplaces and discovered after failure analysis that the chips were remarked, recycled, or fully counterfeit. Contributors on engineering forums describe that when such parts are bought through brokers or from other contract manufacturers, you are essentially on your own: if they turn out to be fake, you are “pretty much screwed” because there is no contractual path back to the original manufacturer.

Authorized distributor verification is therefore not a box‑ticking exercise. It is a core piece of your risk management for safety, uptime, and regulatory compliance.

What “Authorized Distributor” Really Means

The language around distributors can confuse teams that do not live in the component world every day. In purchasing jargon, the factory means the actual manufacturer (for example, a semiconductor brand or a major controls OEM). Franchised or authorized distributors are companies that have formal, contractual relationships with the manufacturer to sell its products on its behalf, typically in specified regions or market segments. Examples in the electronics domain include the big global catalog distributors and large regional players that show up on the manufacturer’s own “where to buy” page.

Everyone else is some flavor of independent distributor or broker. These firms may be honest and technically competent, and they can be very helpful when you are chasing end‑of‑life parts or oddball legacy stock. However, they are not contractually bound to the manufacturer, they may obtain parts through opaque secondary channels, and if something goes wrong with authenticity or traceability, the manufacturer is under no obligation to stand behind the sale.

The practical implications for risk, availability, and support can be summarized as follows.

| Channel type | Typical situation | Counterfeit / traceability risk | OEM warranty and support | Price and availability behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factory direct | High‑volume or strategic accounts buy directly from the manufacturer | Very low, with strong traceability | Direct technical and warranty support; often best for complex failures and root‑cause analysis | Strong on current products, less flexible on small quantities; minimum order sizes and longer negotiation cycles |

| Authorized distributor | Main channel for most buyers; formally appointed by the manufacturer | Very low when purchased through official locations; reputation heavily at stake | Manufacturer will typically stand behind product; failure analysis and field support are accessible, especially for meaningful volume | Competitive pricing, broad availability on active lines, standard lead times; rarely the cheapest option but usually predictable |

| Independent broker / gray market | Used when parts are obsolete, on extreme allocation, or for short‑notice emergencies | Highly variable; includes good stock, but also reused, remarked, or counterfeit parts; little traceability | Very limited. If parts are bad or fake, recourse is often only to the broker, and even that may be weak | Can offer lower prices or faster delivery for scarce parts, but deep discounts versus mainstream quotes are a red flag |

| Online marketplace seller | Third‑party seller on general e‑commerce platforms | Similar to brokers; mix of legitimate and illegitimate suppliers; very little systematic vetting | Manufacturer will rarely acknowledge warranty if bought via an unknown marketplace seller | Attractive advertised prices, but with non‑trivial risk of gray‑market or counterfeit stock |

Your verification process should aim to keep most of your spend in the first two channels and reserve the latter two only for managed exceptions with additional controls.

Step 1 – Confirm the Company Is Real and Stable

Before you worry about “authorized,” make sure the company exists in a meaningful, durable way. ERAI’s guidance on online supplier verification is simple but effective: treat basic due diligence as a non‑negotiable first filter.

Start by checking corporate registration using the relevant Secretary of State or national corporate registry sites. Confirm that the company is actually incorporated, see how long it has existed, and note the listed officers and registered address. New entities with no history are not automatic disqualifiers, but they warrant more caution for critical parts.

Next, validate the physical presence. Using tools like online maps and satellite imagery, compare the claimed address to what is on the ground. A vendor claiming to operate a large warehouse or distribution center that appears, from aerial imagery, to sit in a small residential house or strip‑mall mailbox should trigger hard questions. ERAI explicitly suggests using things like UPS Store location searches to detect when a supplier is effectively operating out of a mail drop while presenting itself as a substantial facility.

Trade references are another core check. Both ERAI and global sourcing specialists emphasize that it is not enough to collect references on a form; you must actually call them. Ask existing customers about on‑time delivery, quality consistency, responsiveness during problems, and any history of disputes. Cross‑check online search results for the company name, address, and phone number; look for patterns of unresolved complaints, repeated rebranding, or virtual office use.

Modern supplier‑intelligence firms such as Veridion and Z2Data extend this idea by aggregating public data about company size, digital presence, industry classification, and even litigation and sanctions history. Whether you use such platforms directly or rely on an internal risk team, the principle is the same: use independent data to validate the story the salesperson is telling you.

If a potential distributor cannot pass these basic identity and stability checks, do not rely on any “authorized” claims that follow.

Step 2 – Verify Authorized Status With the Manufacturer

Once you are confident the company is real, shift to the central question: is this organization actually authorized by the manufacturer for the parts you care about?

Counterfeit‑avoidance guidance from ERAI is very clear here: when a company claims to be an authorized distributor, verify that claim directly with the original manufacturer. Most serious manufacturers publish distributor lists on their websites by country or region. Use those directories as your starting point. Look for the company’s legal name, not just its marketing brand. If you do not see it, treat the claimed authorization as unproven.

Do not stop at the website. For high‑risk lines, call the manufacturer’s regional sales office or channel management team and ask explicit questions. Confirm whether the distributor is authorized for your geography, for your product family, and for the kind of business you will be doing (panel building, OEM, MRO, or resale). It is common for a distributor to be authorized for one region and not another, or for one product line and not the full portfolio.

When the manufacturer confirms authorization, keep written evidence. Save email confirmations or distributor listings, because these will matter if you need to escalate a field failure or contest a counterfeit suspicion later.

Remember that authorized status is not permanent. Manufacturers change channel strategies, consolidate, or terminate agreements. Build a simple calendar reminder to re‑verify key distributors on a periodic basis, for example annually or when you see branding or company names change.

Step 3 – Check Quality Systems and Certifications

Authorized status tells you there is a contractual relationship, not that the distributor runs a disciplined operation. Before you trust them with high‑consequence hardware, examine their quality management system.

Industrial sourcing experts at Ever Trust Tools and 889 Global Solutions emphasize the importance of confirming adherence to recognized quality standards such as ISO 9001 and, where relevant, industry‑specific schemes like IATF 16949 for automotive or AS9100 for aerospace. Do not accept a logo on the website as sufficient. Ask for current certificates, then verify them through official registrars or tools like IAF CertSearch, as Veridion recommends. Check that the certificate covers the correct legal entity, site, and scope of activities.

Beyond certificates, ask how the distributor handles incoming inspection, storage, and handling of sensitive components. Even though, as practitioners on electronics forums note, distributors typically do not functionally test standard devices, they remain responsible for proper environmental controls, ESD protection, moisture‑sensitive device handling, and traceability record‑keeping. For industrial automation, mismanaged storage can mean corroded terminals, degraded capacitors, or compromised safety devices.

Learn whether the distributor can provide Certificates of Conformity for each shipment, and whether those CoCs specify which characteristics they verify. Quality professionals on machining forums describe using structured first‑article inspection reports and clearly defined critical characteristics; your distributor should be equally comfortable documenting how they ensure form, fit, and function for what they ship.

If a distributor cannot explain its quality system in plain language or only offers vague assurances instead of concrete processes and documents, consider that a serious warning sign regardless of pricing.

Step 4 – Evaluate Communication, Competence, and Commercial Terms

In the long run, a distributor is not just a box‑shipper; it is a project partner. Mechanical Power’s guidance on supplier evaluation for machinery parts highlights communication as a two‑way factor that is critical to the relationship’s success, and that advice holds for industrial controls as well.

Before you commit, see how the distributor behaves under small, low‑risk tests. Engage a sales or technical representative early, ask detailed questions, and see how promptly and accurately they respond. Place a modest trial order by phone or email and track how quickly they confirm details, acknowledge receipt, and provide shipping information. Unstructured, slow, or error‑prone communication during these early steps is a strong predictor of frustration when your project schedule gets tight.

Discuss expectations clearly. Experienced buyers insist on straightforward conversations about product versions, substitution policies, delivery schedules, packaging standards, and what happens when things go wrong. Put particular focus on last‑time‑buy situations and product change notifications, because distributors play a key role in making sure your design is not stranded on obsolete hardware.

On pricing and payment, advice from both Mechanical Power and 889 Global Solutions is pragmatic. Do not blindly accept the first quote, and do not chase the absolute lowest price at the expense of all other factors. Aggressively low pricing compared with multiple reputable quotes is a classic red flag for gray‑market or suspect stock, as practitioners on electronics forums warn. Aim for long‑term value, not short‑term savings, and negotiate payment terms that support your cash flow without forcing the distributor into unhealthy behavior.

Finally, review the breadth of the product range. A distributor with a deep and relevant catalog can save you significant engineering and purchasing effort by becoming a one‑stop source for related components. However, breadth should not compensate for weak quality or dubious sourcing; it is better to qualify multiple focused distributors than to rely on a single broad but unreliable one.

Step 5 – Assess Counterfeit and Quality‑Risk Controls

Even through authorized channels, failures happen. And when you inevitably need to step outside authorized distribution for obsolete or urgently needed parts, the risk of counterfeit and substandard product increases sharply. Your verification process should therefore include specific questions about how the distributor manages authenticity and quality risk.

Electronics professionals point out that most franchised distributors do not perform routine authenticity testing on standard components; they rely on the factory’s processes and their controlled supply chain. Some may offer additional services such as programming or basic functional testing for microcontrollers and flash devices, but these are exceptions rather than the norm. That means you must treat authorized status as one layer of protection, not as a complete solution.

At a minimum, require traceability. Ask whether the distributor can provide manufacturer date codes, lot numbers, and original packing labels for the devices or modules you are buying. For high‑risk or safety‑critical parts, consider specifying that they must ship in original factory packaging, unopened, unless you explicitly request kitting or breaking bulk.

When dealing with independent brokers or secondary channels, significantly raise the bar. ERAI recommends using its own membership resources and alerts to screen out companies with known issues, and encourages buyers to report any entities that misrepresent certifications or membership. For critical parts from non‑authorized sources, insist on documented test plans, third‑party lab reports where appropriate, and detailed photos of markings and packaging prior to shipment.

Practical industrial advice from Ever Trust Tools applies here as well: use sample evaluations and small pilot orders to detect poor workmanship, inconsistent labeling, or suspicious packaging before you expose production equipment. Examine material feel and weight for mechanical items, inspect edges and machining quality, and perform functional tests on representative units.

Remember that your design and manufacturing teams can help. If authentic parts from an authorized distributor fail after assembly, expect the manufacturer to support failure analysis, but be prepared for a slow and politically complex process where the factory, the contract manufacturer, and your design team may each suspect the other. Having your own basic analysis capability and clear records of sourcing, handling, and testing will help accelerate resolution.

Step 6 – Make Initial Orders a Controlled Experiment

Even when a distributor looks good on paper and has confirmed authorized status, you should treat your first orders as controlled experiments rather than all‑in commitments. Both Ever Trust Tools and 889 Global Solutions recommend starting with small trial orders after sample approval to validate that real‑world production and logistics match the promises made during evaluation.

For an automation project, that might mean sourcing a subset of PLC racks, selected drives, or a few hundred safety relays from the new distributor, while keeping the balance of risk on established suppliers for a period. During this pilot phase, track on‑time delivery performance, accuracy of picks, condition of packaging, completeness of documentation, and how the distributor handles minor deviations or questions.

Use that data to make a go or no‑go decision on expanding the relationship. If the distributor handles the pilot well, you have real evidence to justify migrating more business. If they struggle with basic execution, you have contained the damage and avoided discovering the problem only when the entire plant schedule depends on them.

This concept aligns with how regulators like the FDA think about process validation for manufacturing in general. The agency’s process validation guidance emphasizes a lifecycle approach with design, qualification, and continued verification stages. You can apply the same thinking to your supply base: deliberately design your supplier selection criteria, qualify distributors with controlled pilot orders, and then continue to monitor performance throughout the relationship.

Step 7 – Move From One‑Time Vetting to Continuous Monitoring

Traditional supplier questionnaires and audits conducted once a year are no longer enough. Z2Data notes that static surveys can miss fast‑moving risks such as political instability, natural disasters, cyberattacks, or sudden financial distress. Veridion makes a similar point by arguing for continuous supplier intelligence that updates profiles and risk scores as new information emerges.

For authorized distributors of industrial parts, continuous monitoring means several things. First, track operational performance: on‑time delivery, lead‑time consistency, quality issues per shipment, and responsiveness to technical questions. Turn those into simple internal metrics so that your procurement and engineering teams can see trends.

Second, watch the broader risk landscape. Specialized data platforms can now flag when a supplier’s parent company shows signs of bankruptcy, when a facility experiences a major fire, or when a region faces new sanctions or labor unrest. Even if you do not subscribe to such platforms directly, your corporate risk or supply‑chain team may be using them; make sure your critical distributors are included in that monitoring.

Third, keep a backup plan. Veridion and Z2Data both emphasize the value of pre‑vetted backup suppliers and diversified sourcing. For high‑impact components, aim to have at least two authorized distributors qualified and commercially active, even if you keep the majority of volume with one primary partner. Switching under duress to a broker or marketplace seller because your sole distributor suddenly fails is exactly what good verification and monitoring are meant to prevent.

Finally, avoid survey fatigue. When you re‑assess a distributor, do not send the same bloated questionnaire every year. Treat each survey or audit as an opportunity to refine your understanding, fill in gaps identified by external data, and test specific risk controls rather than re‑collecting basic information.

Part‑Level Verification at Receiving

Verifying the distributor is necessary but not sufficient. You also need robust part‑level verification as material arrives at your dock, particularly for high‑value or safety‑critical items.

Traditional methods rely on manual label checks, tape measures, and paper manifests. On busy industrial sites, those checks are often rushed or skipped, and mismatches are discovered only when technicians try to install a component weeks later. By then, fixing the error means rework, crane rescheduling, or extended downtime.

Newer approaches, like the AI‑based visual verification described by Tiliter for industrial construction sites, move part verification up to the receiving point. Standard photos taken when parts arrive are automatically compared against digital records and engineering drawings. The system flags incorrect or missing parts and subtle variations in dimensions or connection types. The key advantage is that it does not demand exotic scanners or deep integrations; it can be layered onto existing receiving workflows while still generating a visual audit trail for each part.

Whether you use advanced vision systems or disciplined manual checks, the principle is the same. Treat receiving as the last controlled gate where you can catch errors before they propagate into installation and commissioning. Combine that with documentation checks, such as confirming that serial numbers, firmware revisions, and safety markings match your expectations and the manufacturer’s data sheets.

This is also where regulatory experience from sectors like pharmaceuticals and food can inform best practice. Rules such as DSCSA for drug serialization and 21 CFR Part 117’s supply‑chain program requirements emphasize verification of product identifiers and supplier approval before products are accepted into the distribution chain. You can adopt the same mindset for industrial parts: if identity, authorization, or documentation do not line up, do not let the part onto the shelf.

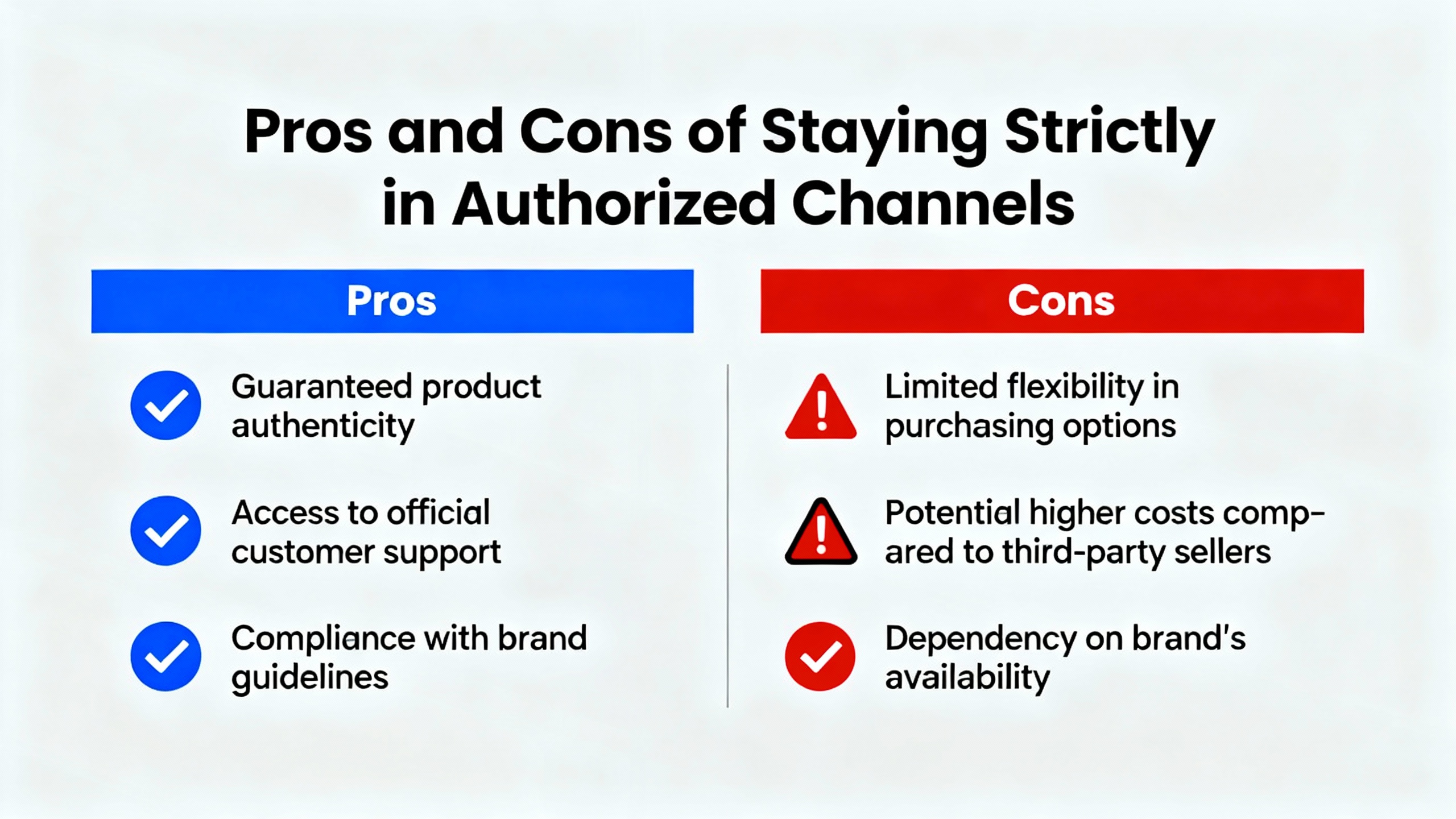

Pros and Cons of Staying Strictly in Authorized Channels

Some teams argue that they should use authorized distributors exclusively, while others routinely rely on brokers, especially for legacy equipment. In practice, most mature organizations land somewhere in the middle, and a clear view of the trade‑offs helps you decide where you want to be.

Authorized distributors excel at predictability, warranty protection, and low counterfeit risk. They are typically integrated into the manufacturer’s product change notifications and life‑cycle management, which reduces the chance that you design around a device that is quietly going obsolete. When genuine parts fail, you have a clear escalation path that may involve the manufacturer’s applications engineers, field quality teams, and, for serious issues, full failure analysis.

However, authorized channels can have limitations. They may be constrained by territory or sector rules and cannot ship to certain project locations. They may have limited access to very old or niche parts, and their lead times during global shortages can be long. Price flexibility depends heavily on your volume and relationship.

Independent brokers and secondary channels can be invaluable when you must support old control platforms that are no longer in mainstream distribution, or when you face a genuine line‑down situation and authorized channels cannot deliver in time. In those cases, the ability to locate stock anywhere on the globe and move it quickly has real value.

The cost is higher risk. Gray‑market channels have historically been fertile ground for counterfeit and substandard products, particularly in electronics. As ERAI and engineering communities warn, if a broker offers material far below prevailing market prices, you should assume that risk, not generosity, is driving the quote. You can mitigate some risk with heavy inspection and testing, but you will never fully replicate the confidence provided by a clean, authorized chain of custody.

The most pragmatic strategy is to declare authorized distributors as your default, document strict criteria and additional controls for any exception, and keep your engineering and quality teams involved in each high‑risk decision.

Building an Internal Playbook

All of this effort is wasted if it lives only in the heads of a few experienced people. The organizations that handle distributor risk well tend to codify the process in clear, lightweight playbooks.

At a minimum, your playbook should define who is responsible for each part of distributor verification, what evidence must be collected, and what thresholds trigger escalation or rejection. Borrow ideas from regulated sectors, where supplier approval and supply‑chain risk management are treated as auditable processes rather than ad‑hoc judgments. For example, food manufacturers operating under 21 CFR Part 117 are required to maintain documented supply‑chain programs, including supplier approval and verification activities commensurate with the hazards involved.

In an industrial automation context, that can translate into standard checklists for new distributors, templates for reference calls, documented procedures for confirming authorization with manufacturers, and clear rules around when you may or may not buy through brokers. Integrate these rules into your ERP or purchasing system where possible, so that unauthorized distributors cannot be added casually, and exceptions require deliberate approval.

Most importantly, align engineering, procurement, quality, and legal on why this matters. When everyone understands that a dubious bargain on safety relays today can become a safety incident investigation tomorrow, it becomes much easier to defend disciplined choices in the face of short‑term budget pressure.

Brief FAQ

How can I quickly tell if a “too good to be true” quote is risky?

Start by comparing the quote against pricing from known authorized distributors for the same brand and part number. If a new supplier is dramatically below that range without a clear explanation, you should treat it as a risk signal. Combine that with basic checks on corporate registration, physical address, and references. As electronics practitioners often remark, if the price is far below everyone else’s, you are probably paying for risk.

Is it ever acceptable to buy from brokers or marketplace sellers?

It can be acceptable as a managed exception, for example when you must support legacy equipment and no authorized channel can supply the part. In those cases, treat the purchase as high risk. Use resources like ERAI to screen potential suppliers, require as much traceability and testing as practical, and avoid designing new projects around parts you can only obtain this way.

How often should I re‑verify a distributor’s authorized status?

Re‑verify when anything material changes: significant company rebranding or mergers, manufacturer acquisitions or channel reorganizations, or major shifts in your own usage of the product line. In addition, a simple annual check for your top distributors is usually sufficient to catch changes in authorization or certification before they surprise you during a crisis.

Do I really need third‑party supplier‑intelligence tools?

You do not need them to get the basics right. Careful identity checks, manufacturer confirmation, and disciplined pilot orders will handle a large share of risk. However, as your supply base grows and your projects span more regions and regulations, tools like those described by Veridion and Z2Data become powerful force multipliers. They can surface hidden risks, such as sanctions or factory incidents, faster than manual methods.

In industrial automation, trusted hardware is the foundation of every reliable system. Treat authorized distributor verification as a core engineering control, not administrative overhead, and you will earn something more valuable than a low price: a supply chain your operators and customers can depend on when it matters most.

References

- https://collected.jcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1022&context=fac_bib_2025

- https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3429&context=doctoral_dissertations

- https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2537&context=etd

- https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=17289&context=dissertations

- https://www.eng.auburn.edu/~uguin/pdfs/Access-2019-Blockchain.pdf

- https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/files/final_submissions/211

- https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Process-Validation--General-Principles-and-Practices.pdf

- https://www.nap.edu/read/24862/chapter/5

- https://www.cdse.edu/Portals/124/Documents/jobaids/ci/deliver-uncom-supply-chain-risk-management-job-aid.pdf

- https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-117

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment