-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Siemens 6SL3 210-1KE23 G120 Drive Equivalent: Choosing Reliable Alternative Variable Speed Drives

When you specify a Siemens SINAMICS G120 drive like the 6SL3 210-1KE23 and then discover it is on allocation, discontinued, or simply outside your budget, you have two choices. You can park the project and wait, or you can qualify an equivalent variable speed drive and keep the schedule moving. As a systems integrator, I have rarely had the luxury of waiting. Production dates and shutdown windows do not move just because a single part number is hard to find.

This article walks through how to think about “equivalents” to a Siemens 6SL3 210-1KE23 G120, using proven selection principles from manufacturers such as ABB, Eaton, Invertek Drives, AutomationDirect, and others. The goal is not to push you toward one particular brand, but to make sure that when you plug an alternative drive in, it behaves like a trusted project partner instead of an unpleasant surprise.

Why You Might Need an Equivalent to a Siemens G120

On paper, a Siemens G120 like the 6SL3 210-1KE23 is a very capable, mainstream variable frequency drive (VFD). In practice, several things routinely push engineers to look for alternatives.

First, supply chain realities. Large OEMs can be subject to global component shortages, extended build times, and regional allocation rules. I have seen drives with quoted lead times that would exceed an entire plant build.

Second, lifecycle and portfolio changes. A single G120 variant can quietly reach end of sale while the family continues. Local stocking distributors then have only residual inventory, and your “standard” part effectively disappears mid-project.

Third, mixed fleets and support strategies. Many plants prefer to consolidate on one or two core drive families for spares, tools, and training. If the rest of your site already leans toward a different vendor, you may want your “equivalent” to match that standard rather than doubling down on a single Siemens part.

Finally, cost and functionality. Sometimes the original G120 was sized conservatively or selected years ago, and a modern competing drive can deliver the same performance at a lower total cost of ownership, especially when you factor in energy efficiency and diagnostics.

Whatever the trigger, the challenge is the same: translate “6SL3 210-1KE23” into a neutral set of requirements that you can use to qualify alternative variable speed drives with confidence.

Quick Primer: What a VFD/VSD Actually Does

Before we translate part numbers, it is important to be precise about what is being replaced.

According to ABB and other major manufacturers, a variable frequency drive (VFD) is an electronic motor controller for AC motors that converts fixed-frequency AC to DC and then back to a controlled AC output at variable frequency and voltage. The practical effect is straightforward: the drive controls motor speed, torque, and acceleration instead of running the motor at full synchronous speed all the time.

Industry sources often use the term variable speed drive (VSD) a bit more broadly. A VSD is any electronic or electromechanical arrangement that varies motor speed, for AC or DC machines, by changing frequency, voltage, or both. In most modern industrial plants, however, that VSD is implemented as a VFD feeding a three‑phase AC motor.

Internally, the architecture is consistent across brands:

Rectifier section converts the incoming AC supply to DC. DC bus stabilizes and filters that DC voltage. Inverter section uses IGBTs and pulse width modulation to synthesize the output AC at the desired frequency and voltage.

Drives from Siemens, ABB, Eaton, Invertek, and others all follow this basic pattern. The differences that matter for an equivalent are in current ratings, control algorithms, thermal design, environmental protection, safety features, and how easily the drive integrates into your controls architecture.

One more point from Coast‑style application notes: a VFD controls the motor, while the PLC orchestrates the process. When you swap a G120 for an alternative drive, ensure you maintain the same handshake with the PLC or other supervisory control, or the motor will run but the process will misbehave.

Translating a Siemens G120 into Neutral Drive Requirements

When clients ask me for a “one‑for‑one drop‑in alternative” to a Siemens 6SL3 210-1KE23 G120, I never start with someone else’s cross‑reference sheet. I start with the motor and the application, exactly as selection guidance from Bauer GMC, Chint, Invertek Drives, Eaton, and AutomationDirect recommend.

The table below summarizes the key data points you should extract from the existing drive nameplate and documentation before you even look at another brand.

| Parameter | What to read from the Siemens G120 | Why it matters for an equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Motor power and current | Rated horsepower and full‑load amps | Drives are sized primarily on current, not just horsepower |

| Voltage and phase | Input and output voltage, phase, frequency | Alternative drive must match supply and motor voltage to avoid damage |

| Overload class and duty | Constant or variable torque ratings | Determines whether you need an “industrial/CT” or “pump/fan/VT” style drive |

| Application type | Fan, pump, conveyor, hoist, compressor | Influences torque demand and required control features |

| Environment and enclosure | Panel‑mounted vs exposed, dust, fluids | Drives must have appropriate enclosure rating (IP20 vs IP55/IP66, etc.) |

| Control and I/O | Analog/digital I/O, fieldbus, PLC links | Ensures plug‑and‑play control behavior and avoids recoding PLC logic |

| Safety and compliance | EMC filters, Safe Torque Off, approvals | Maintains safety integrity level and power quality expectations |

Once you have this information, matching an equivalent becomes an engineering exercise rather than a guessing game.

Electrical ratings: horsepower, current, and voltage

Technical guidance from AutomationDirect and Invertek Drives is crystal clear on this point: you do not size a drive by horsepower alone. The full‑load current on the motor nameplate and the drive’s current rating are the primary technical constraints.

Even when the incoming supply is single‑phase and the motor is three‑phase, as in many retrofit cases described by Practical Machinist contributors, the VFD output is three‑phase and must be selected using the drive’s single‑phase current ratings. If the Siemens G120 was already derated for single‑phase input, any alternative must be derated in the same way, or upsized to compensate.

Voltage compatibility is non‑negotiable. The drive input must match the plant supply, and the drive output must match the motor winding connection. Invertek’s application notes remind us that dual‑voltage motors can be wired in star or delta, but the drive itself is built for a single voltage class. Feeding a 230 V‑only drive with a 400 V line will end the replacement project very quickly.

Motor type, torque profile, and application

Selection advice from Bauer GMC, Chint, and Invertek emphasizes that the type of application strongly influences the right drive class.

Pumps and most HVAC fans behave as variable‑torque loads. In these cases, torque varies roughly with the square of speed, and power with the cube. According to analysis compiled by Quincy Compressor and others, running a centrifugal fan at half speed can cut power demand dramatically, often to about one‑eighth of the full‑speed horsepower. Many manufacturers offer dedicated “pump/fan” or “Eco” drives optimized for this behavior.

Conveyors, hoists, mixers, crushers, and many machine axes are constant‑torque loads. They demand high torque at low speed and often require short‑term overloads. Invertek describes these as “industrial” drives with constant‑torque ratings and higher overload capability.

When you replace a Siemens G120 used on a conveyor or hoist, dropping in a pump‑optimized variable‑torque drive from another brand is an invitation to nuisance trips and poor low‑speed performance. The equivalent must match the original torque class.

Environment, enclosure, and cooling

Environment is one of the most common blind spots in drive replacement. Bauer GMC, Eaton, and Invertek all stress checking temperature, humidity, dust, chemicals, and whether the drive is in a ventilated panel or exposed on the machine.

If the G120 sat safely in a climate‑controlled cabinet, an IP20 panel‑mount alternative may be perfectly adequate. If it was mounted on a dusty production line or near washdown areas, any alternative drive should offer protection closer to IP55 or IP66 or be placed in a properly rated enclosure. Invertek reminds installers that high‑protection drives sometimes integrate local controls and isolators; failing to account for that can increase installation cost when you have to add external devices the original never needed.

Cooling is just as important. Application notes from Invertek and selection guides from AutomationDirect highlight that drives generate heat and can raise internal enclosure temperatures by 10–20 °F or more. At moderate climates, that may be tolerable; in a hot plant it can push electronics beyond safe limits. Oversizing enclosures, using flange‑mount drives that shed heat outside the cabinet, or adding cooling are all valid strategies. When swapping a G120 for an alternative, check both the new drive’s loss data and the original panel’s thermal margin.

Control, integration, and safety

While the power electronics in modern drives are similar, the control ecosystems are not. Siemens G120 drives integrate naturally into Siemens PLCs and HMIs. When you move to a different vendor, you must verify how the drive will receive run commands, speed references, and feedback signals.

Selection advice from Eaton and ABB stresses ease of integration, not just raw electrical compatibility. At a minimum, ensure that:

The alternative drive matches the control voltage (for example, 24 VDC vs 120 VAC on digital inputs). Analog inputs support the reference type used in your system (0–10 V or 4–20 mA). Fieldbus options exist for your PLC or DCS, whether that is PROFINET, EtherNet/IP, Modbus TCP, or something else.

On the safety side, modern drives frequently incorporate Safe Torque Off (STO) and ship with built‑in EMC filters to meet regulatory requirements. Invertek’s installation notes show that missing a required STO jumper can leave a drive permanently inhibited. When you replace a Siemens G120 that participated in a safety function, you must either select an alternative drive with appropriate safety ratings or redesign the safety circuit accordingly. Simply bypassing STO to “get running” is not a responsible option.

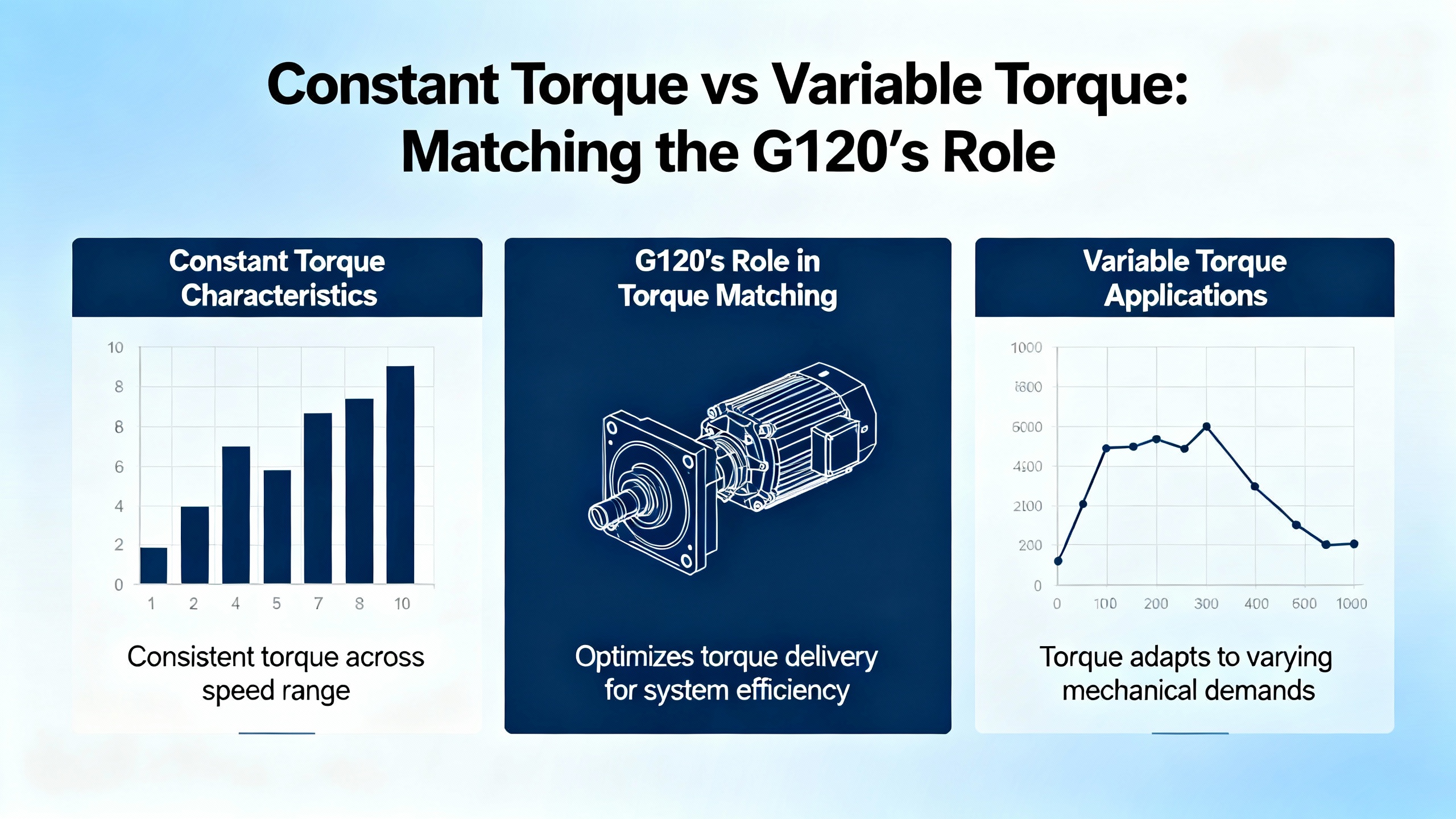

Constant Torque vs Variable Torque: Matching the G120’s Role

Understanding whether your G120 is working in a constant‑torque (CT) or variable‑torque (VT) role is one of the quickest ways to narrow down suitable alternatives.

Guidance from Invertek, Chint, and Quincy Compressor aligns closely on the distinction.

In a variable‑torque application such as a centrifugal fan or pump, torque rises with the square of speed and power with the cube. That means a modest speed reduction can deliver large energy savings. The International Energy Agency and multiple industry case studies report energy reductions in the range of 20 to 60 percent when variable speed drives replace fixed‑speed throttling on suitable loads. Dedicated VT‑rated drives exploit this behavior, sometimes with features like cascade control for multi‑pump systems or advanced torque monitoring.

In constant‑torque applications such as conveyors, hoists, extruders, or crushers, the load demands similar torque across the speed range. Drives in this category are built to deliver high overload capability and often implement sensorless vector or full vector control for tight speed and torque regulation.

The table below summarizes the practical differences you should care about when replacing a G120.

| Aspect | Constant‑Torque (Industrial) | Variable‑Torque (Pump/Fan) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical loads | Conveyors, hoists, mixers, machine axes, crushers | HVAC fans, cooling towers, most process pumps |

| Torque at low speed | High torque required across full speed range | Lower torque needed at low speed |

| Overload capability | Higher short‑term overload between about 150–200% | Lower overload, optimized for efficiency |

| Control method | Vector/torque control often used | Volts/Hertz with pump/fan‑oriented features |

| Energy focus | Process control and mechanical stress reduction | Energy savings via cube‑law behavior |

When someone asks me for a “G120 equivalent,” my first follow‑up is always: is this G120 feeding a fan or pump, or is it turning something with significant torque demand at low speed? Until that question is answered, drive comparisons stay dangerously vague.

Comparing Alternative VFDs: What Really Matters Beyond Nameplate HP

Manufacturers like AutomationDirect, Invertek Drives, Eaton, and Chint all converge on a set of common sizing rules. When you apply them systematically, cross‑replacing a Siemens G120 becomes far less risky.

First, match or exceed the motor’s full‑load current. If the alternative drive offers separate CT and VT current ratings, match the one that corresponds to your application category. Do not rely solely on horsepower tables, especially when you have high‑efficiency motors, unusual duty cycles, or single‑phase supply. Invertek notes cases where a 15 kW drive can legitimately handle an 18.5 kW motor because the motor’s full‑load current is within the drive’s capability, but that decision must be made by current, not by power labels.

Second, respect overload requirements. Many general‑purpose drives are designed for about 150 percent overload for up to sixty seconds, as noted in AutomationDirect’s and Invertek’s documentation. If your process demands more than that, such as long acceleration on heavy conveyors or frequent inching, you may have to size the alternative drive one frame larger than the motor or choose a dedicated high‑overload series.

Third, account for altitude and ambient temperature. AutomationDirect highlights that standard drives are fully rated only up to roughly 3,300 ft of elevation; above that, lower air density reduces cooling and you must derate or oversize the drive. High ambient temperature inside a panel has the same effect. When you compare an alternative to a G120 that ran cool in a large enclosure, be careful if the new mechanical design places a similar‑sized drive into a smaller, warmer space.

Fourth, consider harmonics and EMC. Both Eaton and ABB point out that VFDs can introduce harmonic distortion and electromagnetic interference, especially on long motor leads or sensitive power systems. The original G120 may have had internal filters or been installed with reactances and shields. When you replace it, ensure the alternative drive meets at least the same EMC class and that your installers follow screened‑cable and grounding practices recommended by Invertek and others.

A Practical Replacement Strategy from the Field

In real projects, I follow a simple but disciplined sequence when substituting another VFD for a Siemens G120.

I start on the motor and load. I confirm horsepower, full‑load current, rated voltage, base frequency, and duty cycle. Then I talk to operations about how the equipment is actually used. A pump that was sized for worst‑case conditions but normally runs lightly loaded is a very different duty from a conveyor that starts under full load dozens of times each hour.

Next I document how the existing G120 is wired and controlled. That means noting the control voltage, all digital input and output functions, analog signals, and any fieldbus integration. I also export or capture the G120 parameter set when possible. Even when I cannot import it directly into an alternative drive, it serves as a functional specification of acceleration times, limits, and protections.

Then I short‑list candidate drives from vendors that match the current rating, voltage, CT/VT class, environmental rating, and control features I need. Guidance from Eaton stresses ease of integration, so I put special weight on whether the drive programming and diagnostics will be comfortable for the plant electricians and technicians who live with the system long after I leave.

After that, I check mechanical details: panel space, mounting orientation, cable entry, and clearances for cooling per Invertek’s recommendations. I have seen flawless electrical replacements fail in the field simply because the new drive was shoehorned too close to hot components or had its vents blocked by trunking.

Finally, I plan commissioning with the same care as the selection. That means budgeting time to tune acceleration ramps, current limits, and any PID loops, and to test fault behavior. Studies from sources like ABB and field experience reported by energy‑efficiency programs such as Power Moves show that the biggest long‑term gains from VFDs come when they are tuned to the process, not just powered up at default settings.

Pros and Cons of Staying with Siemens vs Switching Brands

Clients often frame the question as “Is there a non‑Siemens equivalent?” but the real trade‑off is between staying with the Siemens ecosystem and adopting a broader multi‑vendor control strategy.

Staying with Siemens simplifies PLC integration, diagnostics, and training if the rest of the control system is already built around Siemens hardware. The parameter structure, fault codes, and engineering tools are consistent, and you can often reuse commissioning know‑how across projects. In some regions, Siemens also has strong local support, which matters when something fails on a weekend.

Switching to an alternative brand can open up better availability, different price points, and features that fit your plant’s direction. Vendors such as ABB, Eaton, Invertek, and others offer strong pump/fan efficiency features, advanced crane and hoist options, or compressor‑oriented packages. Energy‑efficiency studies from the International Energy Agency and utility programs like Power Moves show that across brands, well‑applied VFDs can reduce energy use by 25 to 85 percent in suitable applications, often with payback in a couple of years for continuously running motors.

The downside of switching is the learning curve and the potential for subtle integration differences. Digital input logic, default ramp times, trip thresholds, and fieldbus diagnostics will not be identical to a G120. In my experience, you manage this risk by standardizing within the alternative brand once you commit and by capturing a site‑specific “drive standard” that documents preferred parameters, wiring practices, and test procedures.

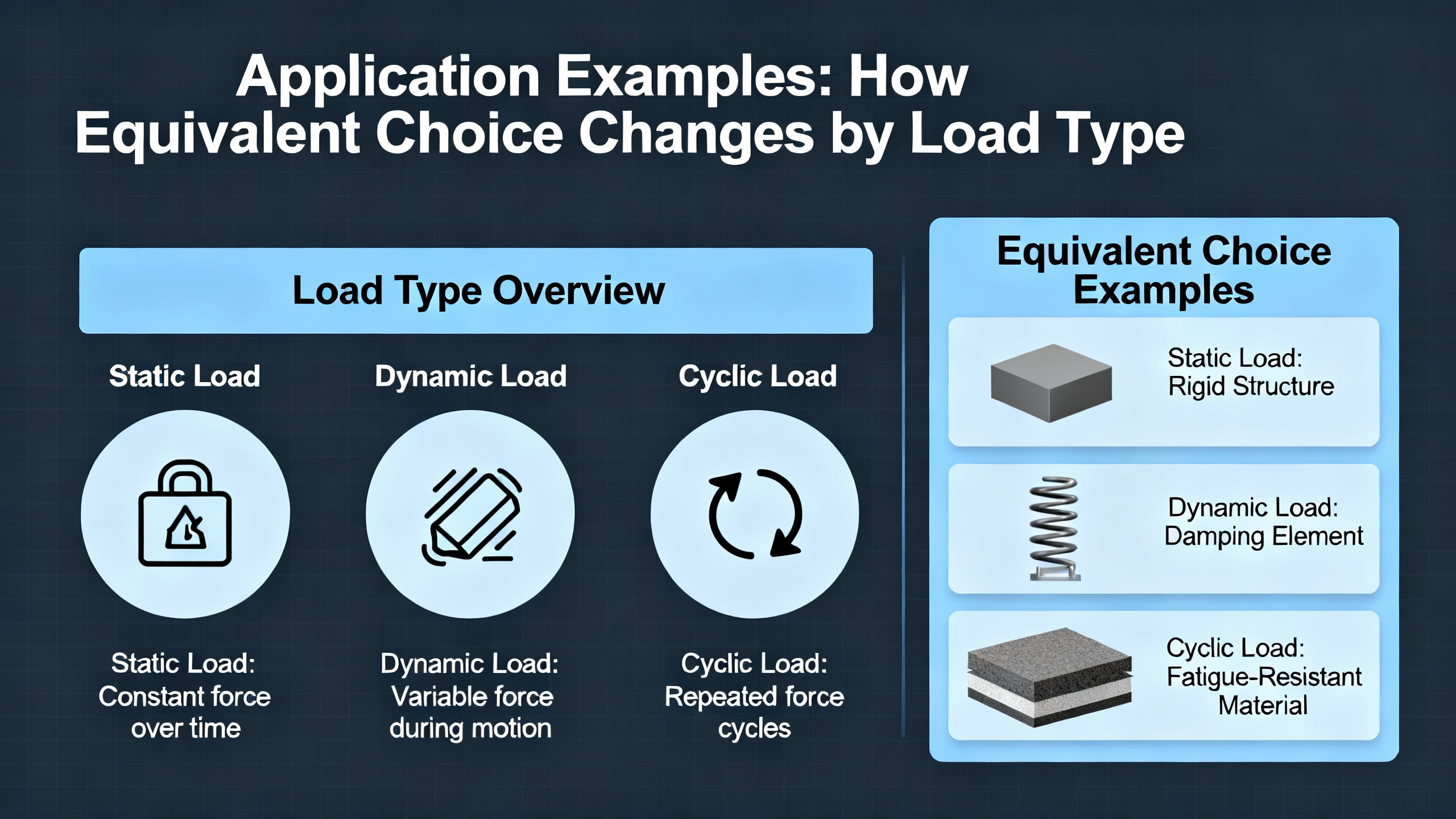

Application Examples: How Equivalent Choice Changes by Load Type

The right equivalent for a Siemens G120 depends heavily on what it is driving. Drawing on case material from sources like Quincy Compressor, Willis Electrical, Prof‑Elec, and Kapton, we can outline a few typical patterns.

On HVAC fans and pumps, the priority is usually energy efficiency and quiet, smooth operation. Replacing a G120 with an alternative VT‑optimized drive that supports low carrier frequencies, integrated PID control, and maybe multi‑pump sequencing can deliver both energy savings and better comfort control. Studies referenced by the International Energy Agency and by vendors such as Kapton and Willis Electrical show that in these variable‑torque applications, cutting fan or pump speeds by even 20 percent can trim energy use by up to roughly 50 percent, with retrofits often paying back within a few years.

On conveyors and general material‑handling equipment, the focus shifts to torque at low speed, controlled starting and stopping, and mechanical stress reduction. Quincy Compressor and Prof‑Elec both highlight that soft ramp‑up and ramp‑down reduce wear on belts, shafts, and bearings and extend equipment life. An equivalent to a G120 on a conveyor should be a constant‑torque drive with robust overload capacity and, ideally, vector control to hold speed under varying load.

On cranes and hoists, safety comes first. Columbus McKinnon’s discussions of crane‑oriented VFDs emphasize features such as sway control, anti‑shock torque limiting, and advanced diagnostics. If your Siemens G120 is part of a hoist or crane system, an alternative drive should offer motion profiles, safety integrations, and diagnostics that are at least as capable. A generic pump drive might turn the motor, but it will not deliver the same safety or handling characteristics.

On compressors, energy costs dominate lifecycle economics. Quincy Compressor notes that more than 70 percent of an industrial compressor’s total lifetime cost is electricity and that variable speed drives can cut energy consumption drastically compared with fixed‑speed control. When replacing a G120 on a compressor, you should prioritize drives that offer stable pressure control, good part‑load efficiency, and integration with the compressor controller.

Across all these examples, the consistent message from field studies and manufacturer guidance is that gains in energy savings, maintenance reduction, and process stability depend more on correct drive selection and tuning than on brand alone.

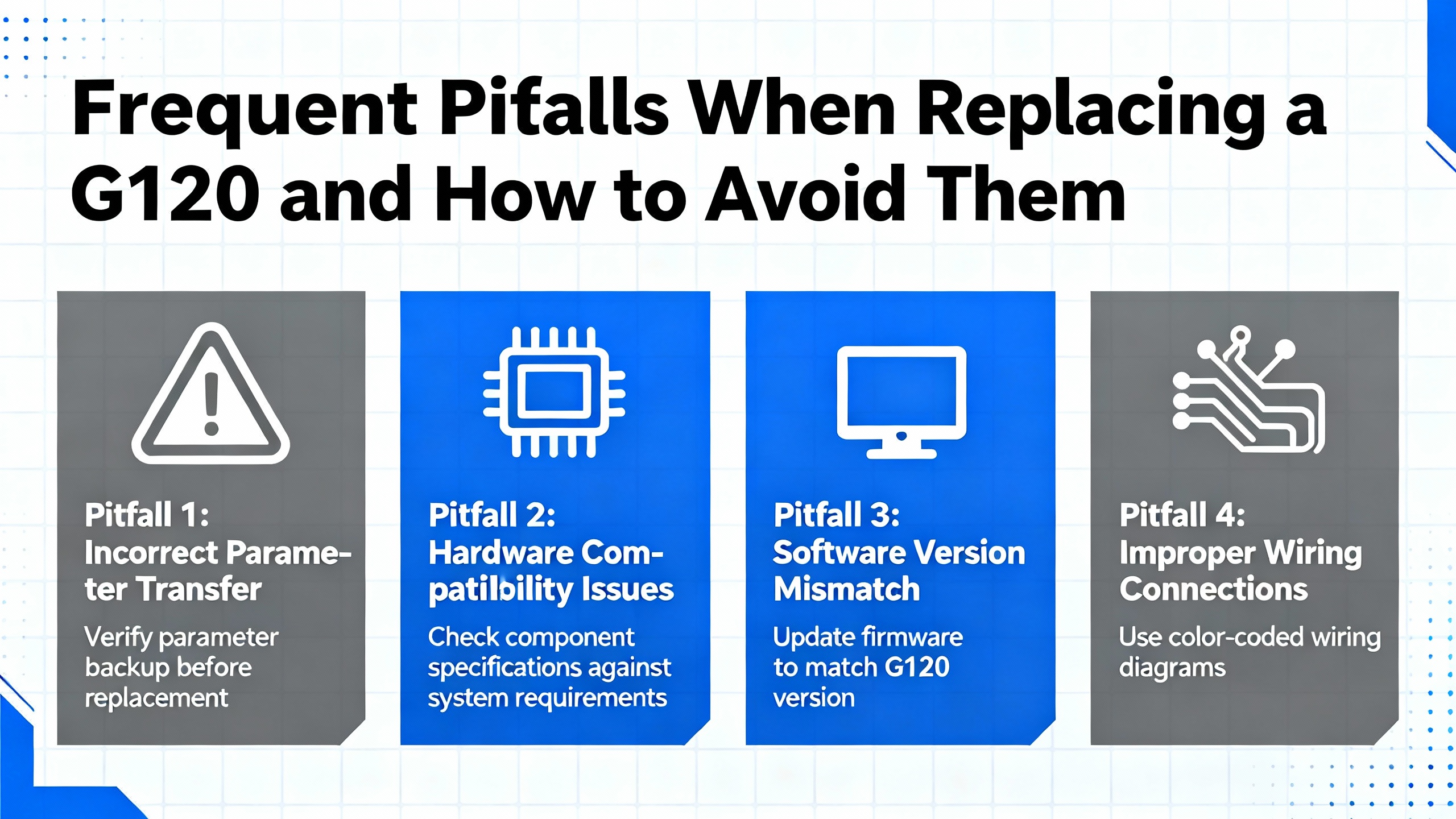

Frequent Pitfalls When Replacing a G120 and How to Avoid Them

Having watched a number of “simple” drive swaps go sideways, I pay attention to a few recurring failure modes whenever a Siemens G120 is replaced by another drive.

One common mistake is undersizing the alternative drive on current and overload. Teams match horsepower, see that the numbers look close, and miss the fact that the original G120 had higher overload rating or a more conservative current margin. Under heavy starting loads or jam conditions, the new drive trips where the old one did not. The cure is to size on current and required overload margin, not just on horsepower labels.

Another frequent issue is ignoring braking and dynamic stopping needs. If the G120 had a braking resistor or was configured for regenerative operation, an equivalent must either support the same features or incorporate another means of handling regenerative energy. Otherwise, deceleration ramps have to be lengthened or the new drive will trip on overvoltage during aggressive stops.

A third pitfall is treating EMC and grounding as afterthoughts. Invertek’s application notes show that good EMC practice depends on screened or armored motor cables grounded at both ends, separation of control and power wiring, and thoughtful panel layout. If the original installation followed these rules and you casually relax them during the replacement, you may inherit nuisance trips, interference on instrumentation, or problems with nearby sensitive electronics.

A fourth problem area is control logic differences. Each brand uses its own default mappings for digital inputs, analog scaling, and fault relays. If you wire the new drive identically to the old one but do not remap these functions, the PLC may see incorrect status bits or the drive may expect an enable signal that the original never needed. Careful review of I/O wiring diagrams and parameter maps prevents this type of mismatch.

Finally, some teams neglect to re‑evaluate protection coordination. Short‑circuit ratings, upstream breaker or fuse types, and motor protection schemes can all change when you substitute a different drive. Even if the new unit runs fine electrically, you must confirm that the total system still meets the site’s safety and compliance requirements.

FAQ: Common Questions About Siemens G120 Equivalents

Can I safely oversize an alternative drive if I am unsure of the motor horsepower?

Forum discussions summarized by Practical Machinist contributors and manufacturer guidance agree on a general principle: a drive that is oversized on horsepower but correctly configured for the motor’s full‑load current is usually acceptable, whereas an undersized drive is a direct risk. The caveat is that some drives require minimum current for good control performance and that protection settings must be adjusted to the actual motor. When in doubt, consult the alternative drive vendor’s application engineers and verify that oversizing will not compromise control or safety.

How much energy can I realistically save by optimising a replacement drive?

Studies gathered by the International Energy Agency and utility programs such as Power Moves report energy savings in the range of roughly 25 to 85 percent for suitable variable‑torque applications, especially fans and pumps that run many hours per year at partial load. Manufacturers like Prof‑Elec, Kapton, Willis Electrical, and Quincy Compressor all provide case examples where proper use of variable speed drives yields substantial reductions in energy bills and fast payback. On constant‑torque loads, savings are more about process optimization and reduced mechanical wear than pure kilowatt‑hours, but they can still be meaningful.

Is it worth standardizing on a single non‑Siemens drive family across the plant?

From a systems‑integration perspective, standardizing has clear advantages: fewer spare part types, common parameter structures, shared tools, and unified training. However, manufacturer guidance from Eaton and others warns against choosing drives on price alone. The best strategy is to standardize on one or two drive families that cover your main application types, including constant‑torque machinery and variable‑torque pumps and fans, and that integrate cleanly with your main PLC platform. If a non‑Siemens drive family meets those criteria and is well supported in your region, standardizing on it for future Siemens G120 replacements can be a sound decision.

Closing Thoughts

Replacing a Siemens 6SL3 210-1KE23 G120 with an “equivalent” variable speed drive is not about finding a part number that looks similar in a catalog. It is about understanding the motor, the load, the environment, and the control architecture well enough that any competent drive from a reputable manufacturer can step into that role without surprises. If you approach the task with the same discipline you would use to design a new drive system, and you lean on the selection and installation guidance from suppliers like ABB, Eaton, Invertek, AutomationDirect, and others, you can treat brand changes as routine engineering work rather than high‑risk surgery. That is how a veteran integrator keeps projects on track and plant teams confident that when they press start, the line will run.

References

- https://www.academia.edu/102546253/A_Study_on_Variable_Frequency_Drive_and_It_s_Applications

- https://digitalcommons.calpoly.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1697&context=eesp

- https://scholar.najah.edu/sites/default/files/Anwer%20Roba_0.pdf

- https://do-server1.sfs.uwm.edu/key/882T9925P1/pdf/716T71P/modern_power_electronics__and-ac-drives.pdf

- https://bauergmc.com/5-factors-to-consider-while-choose-variable-speed-drives.html

- https://new.abb.com/drives/what-is-a-variable-speed-drive

- https://library.automationdirect.com/how-to-select-a-variable-frequency-drive/

- https://www.csemag.com/how-to-select-a-vfd/

- https://www.northamericaphaseconverters.com/driving-efficiency-variable-frequency-drives-vfd-in-the-manufacturing-industry/?srsltid=AfmBOoqe8-CMwaZe4jwKXlteiZ972CeIdUNBSfWeApf6hh8XkRRMnTsq

- https://prof-elec.com/advantages-of-variable-speed-electric-drives-for-industrial-use/

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment