-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Industrial HMI Touch Screens with IP65 Protection: What Actually Works on the Plant Floor

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

Human–machine interfaces have quietly become the primary control surface on most modern production lines. According to market research cited by Global Electronic Services, the industrial touchscreen display market is projected to approach about $1.46 billion by 2026. When you spend your days on the plant floor instead of in a slide deck, you quickly realize that the datasheet line that really separates “nice demo” from “reliable tool” is often the ingress protection rating, especially around IP65.

From years of integrating HMIs into dusty packaging halls, oily assembly cells, and food plants that get hosed down after every shift, I have learned that an IP65-rated touch screen is often the practical sweet spot. It is tough enough to survive in real industrial environments, but flexible and affordable enough to deploy at scale. The goal of this article is to translate that into clear guidance: what IP65 actually means, where it is the right answer, where it is not, and how to design and maintain IP65 HMI touch screens so they stay assets instead of becoming weekly maintenance tickets.

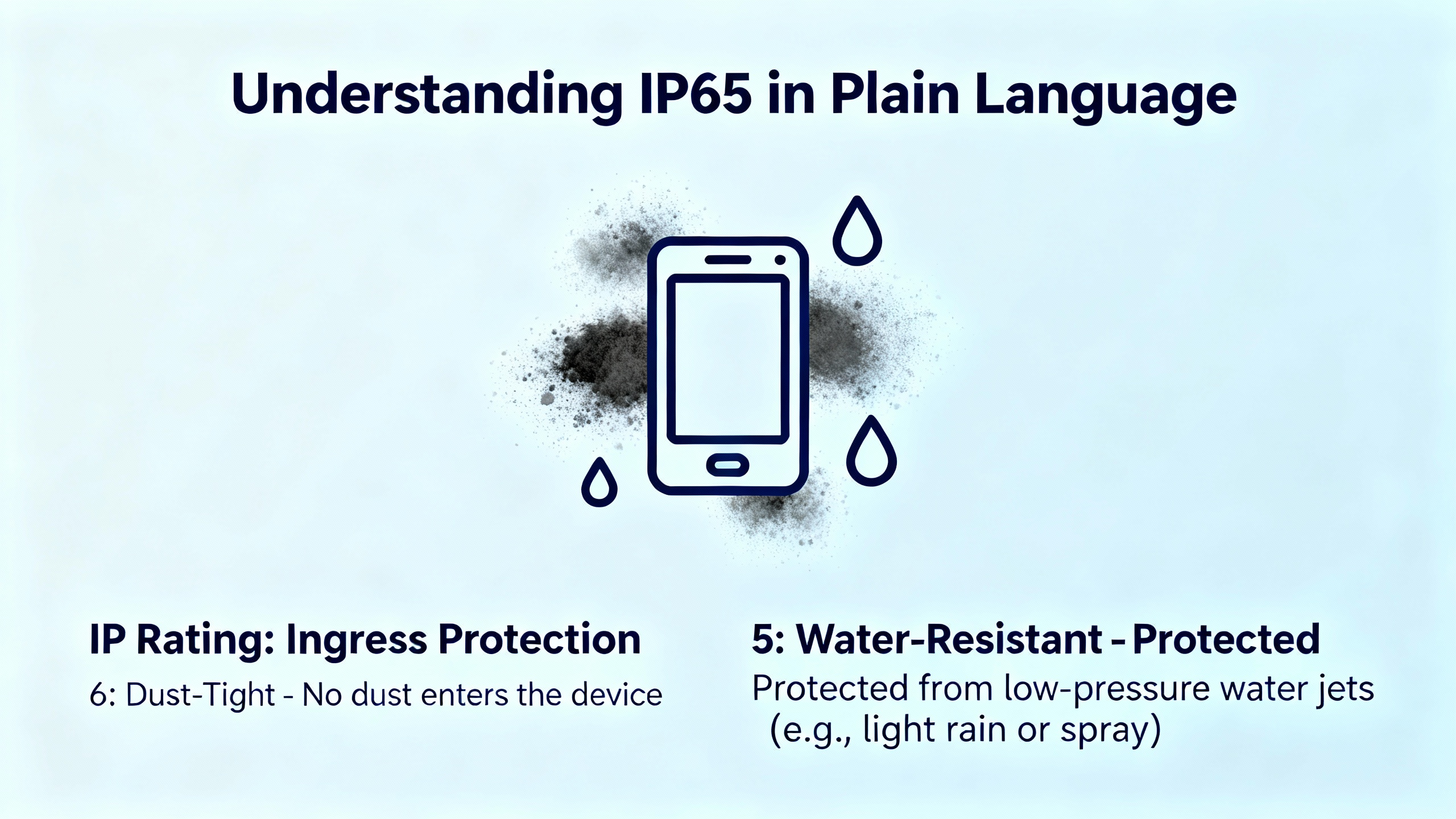

IP65 In Plain Language

Ingress Protection, or IP, is a two-digit code that describes how well an enclosure keeps solids and liquids out. OnLogic explains it succinctly: the first digit rates protection against solids like dust, up to 6; the second digit rates protection against liquids, with higher numbers meaning stronger defenses. IP65 means “6” for dust and “5” for water, so fully dust-tight, and protected against low-pressure water jets or splashes.

Engineers often see a wide range of ratings thrown around, so it helps to put IP65 in context. Guidance from Evelta and OnLogic, along with broader industrial display suppliers, lines up roughly as follows.

| Typical Use Case | Example Rating | What It Is Commonly Used For |

|---|---|---|

| Clean indoor panels, office-like areas | IP54 | Light dust, minimal splashing, controlled environments |

| Dusty or splash-prone industrial fronts | IP65 (front) | Factory assembly stations, machining cells, industrial cabinets and panels |

| Heavy washdown or outdoor exposure | IP66 / IP67 | Food and beverage washdown when paired with proper enclosures, some outdoor |

| Extreme washdown and sanitation | Up to IP69K | High-pressure, high-temperature jets in demanding food or chemical processes |

An IP65 HMI is designed so that dust cannot enter at all, and the protected surfaces can withstand water sprayed from a nozzle. That is very different from office-grade screens, which tolerate a light wipe-down at best, but it is also different from high-end IP69K units that survive high-pressure, high-temperature washdown. Understanding that difference is essential when someone asks for “waterproof” but the line actually gets blasted with hot foam every night.

Front-Bezel IP65 Versus Full-IP Panels

One of the most common mistakes I see in project specifications is writing “IP65 HMI” without stating whether that rating applies only to the front bezel or to the entire device. OnLogic explicitly distinguishes between front IP65 ratings and overall IP65 ratings. A front IP65 screen is dust-tight and splash-resistant from the operator side, but the sides and back are only as robust as whatever enclosure they sit in. A fully IP65 panel PC, by contrast, is sealed across the entire housing, including connectors and cable glands.

In practical terms, this means a panel-mount HMI with an IP65 front is perfectly adequate when it is installed into a properly sealed cabinet door. The rear of the unit is protected by the cabinet itself. This is the pattern you see in a lot of automotive and general manufacturing assembly lines described by Touchwo and similar industrial suppliers.

For a standalone panel PC exposed on a wall or arm mount, the story changes. The entire assembly, including connectors and cabling, must meet the protection requirements. Otherwise the “IP65” label on the front glass is misleading. In those cases, I either select a fully IP65 panel PC or place a front-IP65 HMI inside a sealed enclosure designed to the correct rating. Getting this right on day one avoids awkward conversations the first time production hits an unplanned sanitation audit.

Where IP65 HMI Touch Screens Truly Fit

Several sources, including Evelta, Touchwo, OnLogic, and Valano Industrial PC, converge on the same pattern: IP65 fronts are the workhorse choice for harsh but not extreme environments. Typical examples include assembly stations in workshops that run roughly from about 14°F to 140°F, packaging areas with regular splashes and airborne dust, and production cells where operators lean on the screen all day with oily hands.

For instance, Touchwo highlights IP65-rated screens for factory assembly, combining dust protection, splash resistance, and operating ranges around 14°F to 140°F for typical workshops. Evelta suggests IP65 fronts for dusty or splash-prone areas, reserving IP66 or IP67 plus suitable enclosures for true washdown zones. OnLogic echoes this by recommending panel mounting for food production environments so that the protected front can be wiped or sprayed clean while the rear electronics stay inside a sealed cabinet.

IP65 panels also fit well in semi-outdoor contexts where the HMI is under a canopy or in a kiosk-style housing, especially when paired with high-brightness displays. Valano notes that industrial touchscreen PCs commonly offer much higher brightness (up to roughly 800 nits compared to 200–300 nits for typical office screens), making them suitable for bright factory floors and some outdoor installations when glare is managed.

The pattern I use is simple. If the HMI faces airborne dust and occasional hoses or spray bottles, IP65 is usually the right answer. When you have continuous soaking, aggressive foams, or hot high-pressure jets, you step into IP66, IP67, or IP69K territory, typically with specialized enclosures rather than a standalone HMI alone.

Touch Technology Choices Behind the Glass

Ingress protection is only half the story. The touch technology itself has to match how operators actually use the screen. Across sources like OnLogic, Valano, Boyd, and Things Embedded, industrial HMIs consistently lean on two main families: resistive and projected capacitive (PCAP).

Resistive touch detects input based on pressure between layers. Boyd and Valano both emphasize that these panels reliably register input from almost any object, including gloved hands, styluses, or even a pencil. That makes resistive a natural fit when operators wear conventional work gloves or the environment is grimy enough that direct finger contact is undesirable. The tradeoff is that resistive screens are less sensitive, offer less of the “smartphone” feel, and are not ideal for multi-touch gestures.

Projected capacitive touch, often shortened to PCAP, detects changes in an electrostatic field. OnLogic points out that PCAP enables high-accuracy, multi-touch interaction and a modern, glass-front look, which is ideal for kiosks and many panel PCs. Boyd notes that PCAP supports very long life and a premium user experience, especially when you want gestures like pinch-to-zoom or a more app-like interface. The tradeoff is that glove compatibility depends on glove material and tuning, and the technology tends to cost more than basic resistive.

In real projects, I rarely choose touch technology in isolation. Touchwo, Valano, and OnLogic all weave it into broader decisions about the environment and workflow. In automotive or electronics assembly where operators often wear gloves and perform frequent, precise touches near moving parts, resistive screens on IP65 fronts are common. In supervisory dashboards, gateways, or panel PCs that act more like industrial tablets, PCAP provides smoother navigation and matches operator expectations from consumer devices, especially when gloves are thin or occasional.

Industrial UX practitioners, including those behind Ignition Perspective and OnLogic’s panel PC guidance, also recommend minimizing complex touch gestures in plant HMIs. Across Windows and Linux tests, a single tap behaves like a left-click, while long-presses and multi-touch gestures are inconsistent across systems and screens. Designing primarily around single-tap interactions makes both resistive and PCAP viable, even under mixed operating systems and hardware.

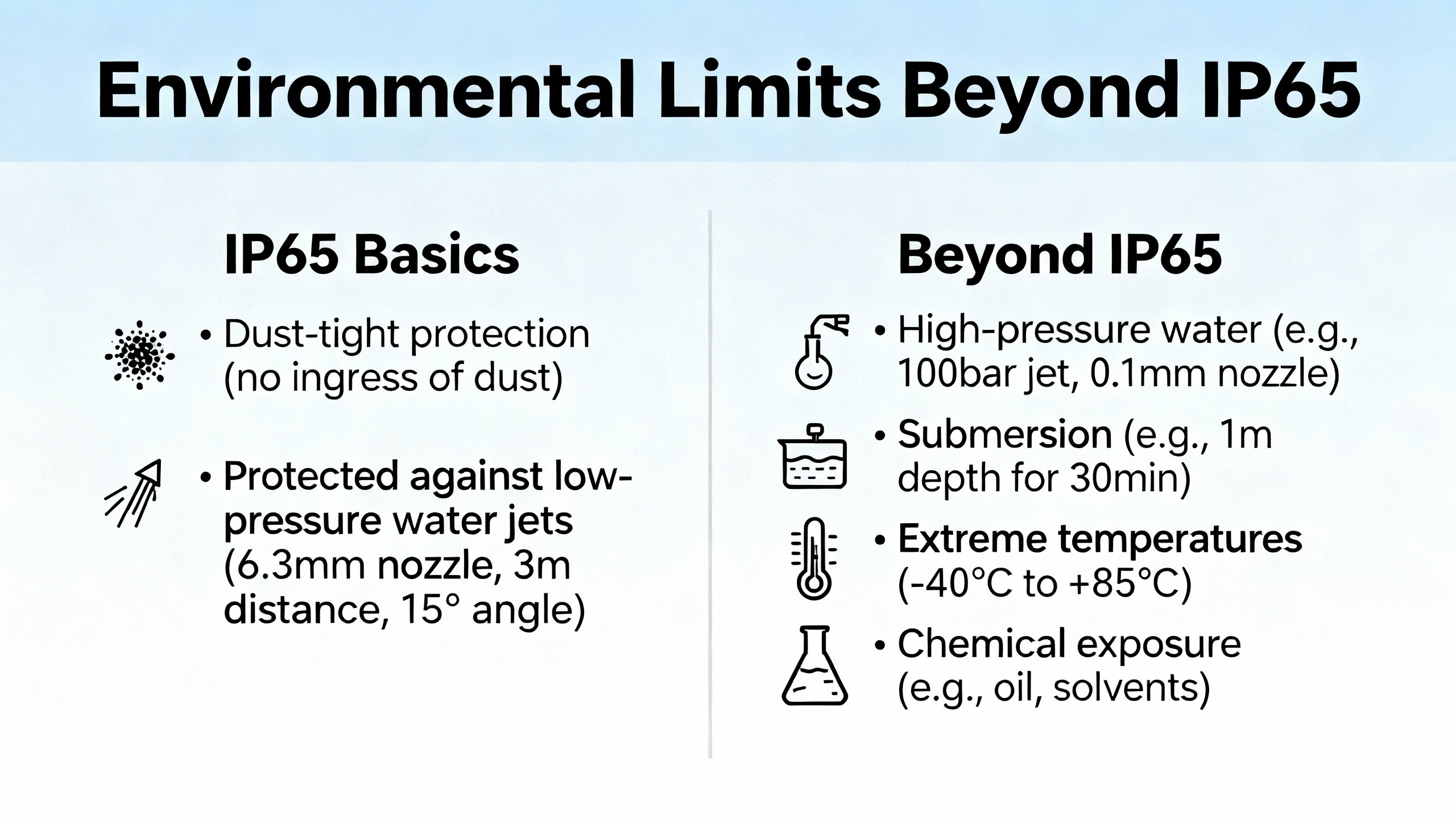

Environmental Limits Beyond IP65

IP65 does not magically make an HMI invincible. Temperature, vibration, and ambient light matter just as much as water jets. Multiple sources, including Evelta, Touchwo, Unisystem, and Valano, give realistic ranges and constraints.

Touchwo and Valano reference typical industrial HMIs and panel PCs that operate from roughly 14°F to 140°F for many workshop and factory environments. Evelta notes that “indoor kiosk” conditions often sit around 32°F to 122°F, whereas many industrial HMIs are specified out to about −4°F to 158°F. If you are putting an IP65 panel in a hot metal-processing bay or a freezer room, you must check those numbers instead of assuming the IP code covers temperature limits.

Brightness is another critical factor. Evelta and Unisystem both stress that bright factory floors and outdoor or sunlit installations require significantly higher brightness than office monitors. Indoor HMIs often start around 300 nits, while bright industrial floors benefit from 500–600 nits. Outdoor or direct-sunlight applications can demand roughly 1,000 nits or more or transflective displays to avoid washout. An IP65 front will not help if the operator cannot read the screen because the afternoon sun is glaring off it.

Mechanical and electrical robustness complete the picture. Valano points out that industrial touchscreen PCs differ from standard desktops by offering shock and vibration ratings, fanless construction, and sealed connectors, often aimed at handling about 1–2 GRMS and 10–15 Gs in specific models. OnLogic recommends pairing fanless designs with solid-state drives so the system tolerates dust, vibration, and frequent power cycling better. IP65 only describes the seal; it says nothing about whether the display will survive constant pounding from a stamping press unless those mechanical ratings are addressed.

Finally, environmental controls around the HMI matter even when the device itself is rugged. IndustrySearch and Unisystem both emphasize using covers, filters, and climate-controlled housings in extreme environments, along with shielding from direct sunlight and chemical exposure. IP65 is a foundation, not a full risk-mitigation strategy.

Designing User-Friendly IP65 Touch HMIs

In my experience, the difference between a “survives” HMI and a “operators love it” HMI is rarely the IP rating alone. It is how you design the screens and interactions around that hardware. A number of sources, including SolisPLC, Ignition Perspective documentation, UX guidance on industrial interfaces, and HMI design best-practice articles, converge on several practical design patterns.

SolisPLC describes typical industrial HMIs with at least ten screens, including plant overview, line or area overview, control, settings, and reusable faceplates for assets such as motors, valves, and pumps. The key is to break complex systems into manageable, hierarchical views. For example, a food processing plant HMI might start with a plant overview, then drill into area overviews for production, packaging, and refrigeration, then into line-level screens, and finally into device-level faceplates. This structure keeps each screen focused while still giving operators a clear mental map.

Navigation deserves particular attention on touch screens in harsh environments. SolisPLC recommends appropriately large touch targets; they cite minimum sizes around 2 cm by 1.5 cm for touch systems. Navigation bars are often better placed at the bottom of machine-mounted HMIs, since operators tapping at the top can accidentally hit other controls or risk overreaching. For distributed SCADA-style systems driven by mouse and keyboard, top navigation is acceptable and familiar. Menu items that are not available because of permissions or system state should be visibly greyed out, and dropdown-style navigation should be clearly marked with indicators so operators understand that items expand rather than activate.

Color and typography are not just aesthetic choices. UX guidance cited by Aufait UX and UX StackExchange contributors stresses keeping strong alarm colors like red reserved for true abnormal conditions. Normal operation should be shown with neutral tones so operators can immediately see when something is wrong instead of wading through a sea of red “normal” indicators. Highly legible fonts, appropriate spacing, and clear hierarchy help reduce cognitive load when the operator is under stress.

There is also a safety aspect to touch interaction. OnLogic and Ignition Perspective both caution against implementing PLC jog or momentary buttons directly on touch screens. Touch contact can be intermittent, and losing contact at the wrong moment can leave an output stuck on or off. For critical motion, I always insist on physical momentary buttons or well-designed sequences, with the HMI providing commands and status but not serving as the only layer of protection.

Finally, consider how text entry works. Perspective and OnLogic note that on-screen keyboards are unavoidable for certain tasks but painful for frequent data entry, especially on resistive screens. Designing your HMI to minimize free-form typing by using numeric pads, recipes, presets, barcode readers, and IDs reduces both operator fatigue and error rates. That is particularly important in washdown or glove-heavy environments where an OS keyboard is a last resort.

Maintenance and Care: Why IP65 Is Not a License to Ignore Cleaning

Dust, grease, and moisture are not theoretical threats; they are what you wipe off every time you open a panel door on a running plant. Fuji Electric’s maintenance guidance for UPS systems explicitly warns that dirt, dust, sawdust, and metal filings accumulate even in seemingly clean environments and can cause shorts on printed circuit boards. The same contaminants collect inside cabinets, around HMI bezels, and in cable glands.

Multiple maintenance-focused sources, including Global Electronic Services, IndustrySearch, and Synchronics, agree on several practical steps to keep industrial touchscreens healthy. Regular cleaning with soft, lint-free or microfiber cloths and mild, screen-safe solutions is essential. Harsh chemicals and abrasive pads scratch protective glass or films and erode coatings, eventually compromising the seal and touch sensitivity. Cleaning fluids should be applied to the cloth, not sprayed directly onto the screen, to avoid moisture creeping into gap seals. After cleaning, the screen should be dried thoroughly and, if necessary, allowed to air dry before power-on to reduce the risk of moisture-related faults.

Global Electronic Services highlights that industrial touchscreens, despite being sealed for durability, are still vulnerable to shocks, vibrations, improper handling, and extreme temperatures. Excessive force on the screen can cause cracks, and a cracked front drastically increases the risk of internal damage from moisture and dust. Synchronics recommends avoiding excessive pressure, using gentle finger or stylus input, and adding screen protectors as sacrificial layers when appropriate.

Calibration and software updates are part of maintenance, not nice-to-haves. GESRepair and IndustrySearch both emphasize that touch accuracy drifts over time and after system or operating system updates. Regular calibration ensures that on-screen buttons align with where operators actually touch, which is critical when they are wearing gloves or working quickly. Keeping firmware and drivers current brings bug fixes, performance improvements, and sometimes resolutions for “ghost touch” or unresponsive areas that operators might otherwise blame on the hardware.

Finally, preventive inspections matter. Synchronics encourages scheduled checks for loose connections, damaged cables, and visible wear, along with keeping simple logs of issues found and corrective actions. That may sound bureaucratic, but when you track recurring problems, you can often attribute them to a specific environmental hotspot or misuse pattern and fix the root cause rather than constantly replacing HMI fronts.

Pros and Cons of IP65 HMI Touch Screens

Once you have looked at enough installations across different industries, the strengths and weaknesses of IP65 HMIs become clear.

On the positive side, IP65 fronts provide a very solid baseline for industrial use. The “6” rating on solids means dust-tight construction, which aligns with the durability goals described by Unisystem and OnLogic for industrial displays. The “5” on liquids allows for spray-down cleaning and protection against splashes, which is exactly what assembly lines and packaging machines experience day after day. Touchwo, Valano, and others note that industrial HMIs are designed for 24/7 operation, with typical lifespans around five to eight years in well-managed environments, and IP65 sealing supports that by keeping contaminants out of the critical areas.

IP65 is also cost-effective compared to higher ratings like IP69K. Valano and OnLogic both point out that more rugged features, including higher IP ratings and specialized housings, raise upfront cost. In many applications, particularly in general manufacturing, investing in IP65 and good enclosures, along with proper cleaning and maintenance, delivers a better return than paying for maximum rating everywhere.

The limitations arise when environments are wetter, hotter, or more aggressive than they first appear on paper. In food and beverage washdown areas, engineering teams often specify IP65 but sanitation practices include hot high-pressure foam. IndustrySearch and OnLogic caution that in such cases you must combine appropriate IP ratings with protective enclosures, seals, and in some cases IP66, IP67, or IP69K designs. IP65 alone is not meant for direct, high-pressure, high-temperature jet exposure.

Another tradeoff is that IP65 says nothing about brightness, shock, vibration, or long-term component availability. Evelta and Valano stress that engineers must still select adequate brightness, processors, memory, and ruggedization levels for the workload. An IP65 HMI with insufficient CPU or RAM for your HMI software will feel sluggish, and no amount of sealing will fix that. Similarly, IP65 does not automatically imply fanless design or solid-state storage, which OnLogic recommends to survive dusty, vibration-prone environments.

In short, IP65 HMIs are an excellent baseline for most harsh but not extreme industrial applications. They excel when paired with realistic environmental assessment, proper mounting, and good HMI design. They fall short when they are treated as a magic waterproof label or specified without regard to temperature, washdown practices, or mechanical shock.

A Practical Specification Pattern for IP65 HMIs

To make this more concrete, it helps to look at combinations of environment, rating, and touch technology that are commonly recommended in industry sources.

| Scenario | Recommended Protection and Touch Choice |

|---|---|

| Compact assembly station with gloved operators | IP65 front in a sealed cabinet door, resistive touch, 5–10 inch class display |

| Standard packaging line control panel | IP65 front-mounted HMI, PCAP or resistive depending on glove use, 10–15 inch range |

| Central control room overview | Lower IP rating acceptable if room is controlled; prioritize resolution and size |

| Food line with frequent spray but no high jets | IP65 front with well-sealed enclosure; consider resistive for frequent glove use |

| Washdown cell with high-pressure cleaning | IP66 or higher with specialized enclosure; IP65 only if fully shielded during wash |

These are not rigid rules, but they are consistent with patterns described by Touchwo, Evelta, OnLogic, and Valano. I use them as a starting point, then refine with site-specific details such as cleaning chemicals, shift patterns, and how much of the HMI content is control versus monitoring.

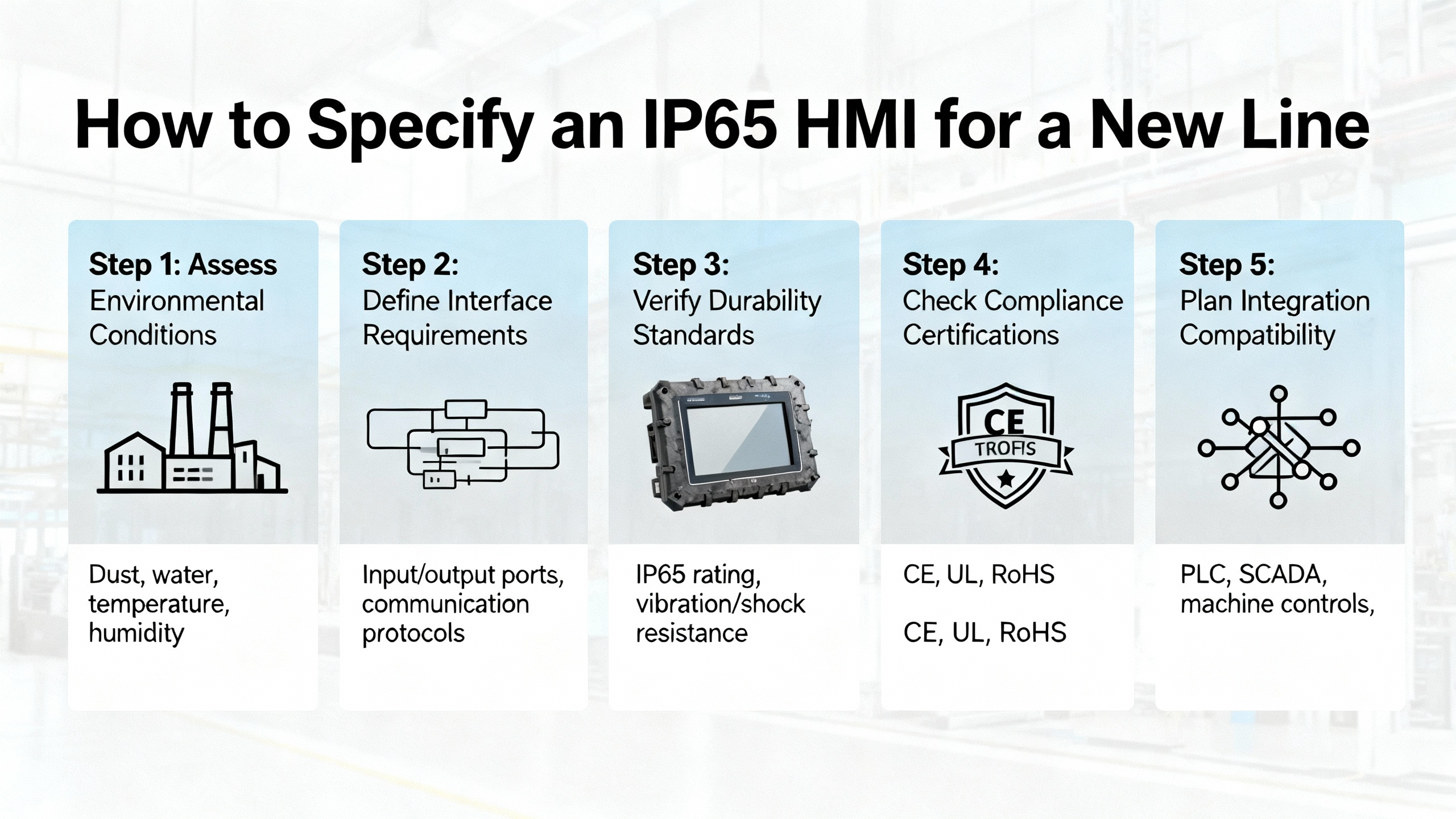

How I Typically Specify an IP65 HMI for a New Line

When I am brought into a project early, I follow a repeatable approach rather than letting the HMI become an afterthought tacked onto the panel layout.

The first step is to understand the operator’s real work. That means documenting what they must see and do from the screen to run the cell safely and efficiently. Sources like SolisPLC and Aufait UX emphasize that good HMIs align with operator mental models and workflows, and I have found that spending time on the floor yields better results than any template.

The second step is to quantify the environment honestly. I look at dust, moisture, temperature swings, and cleaning practices, comparing those observations with guidance such as Evelta’s breakdown of IP54, IP65, and IP66/67 usage. If sanitation will occasionally blast the cell with hot foam, I assume it will someday hit the HMI, no matter what the procedures say.

The third step is to pick touch technology based on PPE and interaction patterns. If operators wear thick gloves and tap the screen dozens of times per minute, resistive panels are the safer bet. If they are mostly using the HMI for higher-level navigation, trending, or diagnostics, PCAP may provide better responsiveness and longer life, as Boyd and Valano suggest, especially when paired with multi-touch gestures for zooming on complex trends.

The fourth step is to define the screen hierarchy and navigation before drawing a single graphic. SolisPLC’s approach of breaking the system into overview, area, line, and device-level screens gives a good blueprint. Navigation bars are planned around bottom placement for touch, with large, neutral-colored buttons and clear highlighting of the current screen. Critical alarms and statuses are reserved for strong colors, consistent with UX alarm guidelines.

Only then do I finalize the hardware model and enclosure details, verifying the IP rating (front versus full), temperature range, brightness, mounting, and connectivity. Valano’s guidance on matching CPU and RAM to workload, along with OnLogic’s recommendations on fanless design and SSDs, helps avoid underpowered systems that frustrate operators despite having the right IP code on the nameplate.

FAQ

Does an IP65 HMI survive high-pressure washdown?

IP65 is designed for dust-tight operation and protection against low-pressure water jets and splashes. Guidance from Evelta and OnLogic makes it clear that true washdown zones, especially where high-pressure or hot jets are used, are better served by IP66 or IP67 devices combined with appropriate enclosures, and in some cases IP69K designs. An IP65-only unit should either be shielded during aggressive cleaning or housed inside a washdown-rated enclosure.

Is IP65 enough for outdoor HMIs?

IP65 can be sufficient for semi-outdoor installations such as sheltered kiosks or covered loading docks when the unit is protected from direct, continuous rain and extreme temperatures. However, Unisystem and Valano emphasize that outdoor applications often require high-brightness or sunlight-readable displays and careful attention to temperature ranges. For fully exposed outdoor use, particularly in harsh climates, you should evaluate higher IP ratings, sunshades, and climate-controlled enclosures.

How often should an industrial touch HMI be cleaned and calibrated?

Maintenance-focused sources like Global Electronic Services, IndustrySearch, and Synchronics recommend integrating touchscreen cleaning into regular plant maintenance, rather than waiting until the screen becomes visibly dirty or unresponsive. The exact interval depends on how dirty the environment is, but in heavy-use stations it is common to clean screens daily or weekly. Calibration should be performed at installation, after significant system or operating system updates, and whenever operators notice drift in touch accuracy. For critical stations, I recommend including calibration checks in scheduled preventive maintenance.

Closing

IP65-rated HMI touch screens hit a practical balance that suits a huge portion of industrial automation projects. When you match that rating with the right touch technology, solid HMI design, and disciplined maintenance, you get a control surface that operators trust and production can rely on day after day. Treat the IP code as one ingredient in a broader engineering recipe, not as a marketing badge, and your HMIs will behave like the dependable project partners your lines deserve.

References

- https://www.mochuan-drives.com/a-news-best-practices-for-designing-user-friendly-hmi-touch-screens

- https://www.boydcorp.com/blog/selecting-the-right-touchscreen-technology.html

- https://synchronics.co.in/5-tips-for-extending-the-service-life-of-industrial-touch-screens/

- https://www.eleken.co/blog-posts/human-machine-interface-design

- https://americas.fujielectric.com/best-practices-for-implementing-hmi-systems/

- https://gesrepair.com/electronic-touchscreen-maintenance/

- https://inductiveautomation.com/blog/optimizing-touchscreen-hmis-applications-for-perspective

- https://maplesystems.com/10-things-to-consider-when-choosing-new-hmi/?srsltid=AfmBOoqogmCAQsfjpSR94B0yzKhVU25FEYbF8r6xTiCHLkqxKyU26wvl

- https://www.solisplc.com/tutorials/hmi-design

- https://www.touchpro.us/post/industrial-touch-screens-common-problems-solutions

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment