-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Buyback Services for Obsolete PLC Inventory: From Dead Stock to Project Capital

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

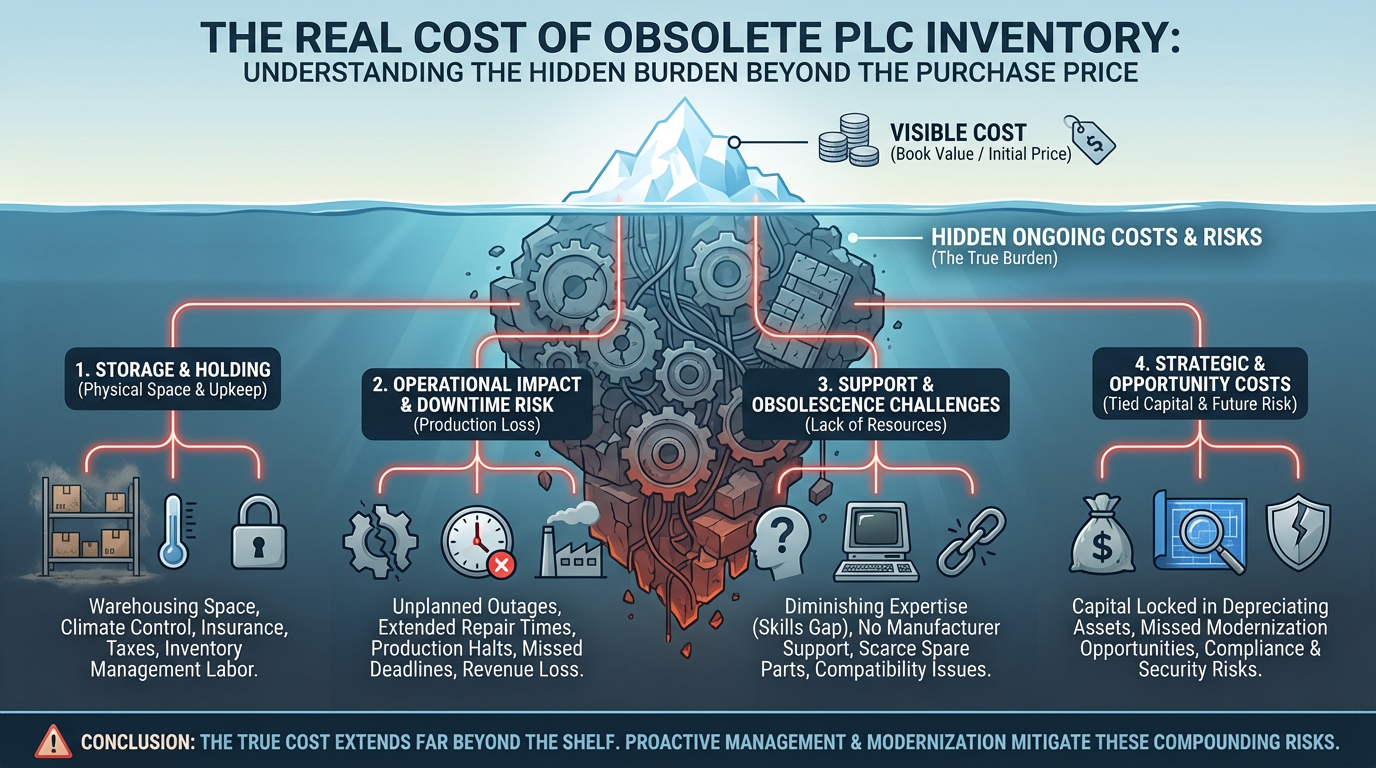

The Real Cost of Obsolete PLC Inventory

If you run an industrial plant or integration business long enough, you end up with a shelf full of obsolete PLCs, I/O cards, and legacy drives. Some of it came from decommissioned lines. Some from overordering “just in case.” Some from migrations that never fully happened. It all looks like insurance, but in financial terms most of it is dead weight.

Inventory specialists consistently describe this kind of stock as excess and obsolete inventory, or E&O. Several accounting and inventory management guides point out that carrying costs alone typically run around 20% to 30% of inventory value every year. Finale Inventory uses that range to illustrate how aging stock quietly erodes profit through storage, insurance, handling, and damage risk. Nest Egg notes that even healthy businesses can end up with roughly 20% to 30% dead stock on the books.

Obsolete inventory is different from simple overstock. Articles from Katana and Itemit describe excess inventory as stock that exceeds current demand but still has realistic sales or usage potential. Obsolete inventory, by contrast, has little or no remaining market value, is unlikely ever to be used in production, and often has to be written down or written off entirely. When you are talking about PLC platforms that OEMs have discontinued and that your plant no longer standardizes on, much of that rack of spares is closer to obsolete than excess.

At the same time, industrial automation suppliers remind us that obsolete does not mean useless. Industrial Automation Co and PLC Automation Group emphasize that obsolete automation parts still support thousands of running lines worldwide, and that downtime from a failed legacy PLC or drive is extremely expensive. That is why the aftermarket for legacy automation hardware exists at all, and why buyback services for obsolete PLC inventory are becoming a practical tool rather than a niche curiosity.

Why Plants End Up with Obsolete PLC Inventory

The pattern that DRex Electronics describes for surplus electronic components will be familiar to anyone who manages PLC spares. Surplus and obsolete inventory typically accumulates because of forecasting errors, project delays or cancellations, engineering changes, end‑of‑life announcements from suppliers, and bulk buys made to secure discounts.

For automation in particular, PLC Automation Group and Industrial Automation Co highlight a structural problem. Control components such as PLCs, drives, HMIs, and servo amplifiers have commercial lifetimes on the order of 10 to 15 years before OEMs end production and begin to reduce formal support. The production assets those parts control, especially in sectors like metals, chemicals, and infrastructure, often stay in service for 20 to 30 years or more. When a vendor issues an end‑of‑life notice, plants scramble to choose between stocking up on spares, fast‑tracking migrations, or living with increased downtime risk.

Katana and other inventory sources underline that technological advances, shifts in customer requirements, new safety standards, and changes in regulations all accelerate obsolescence. A PLC platform that was standard a decade ago can very quickly become a legacy system. At the same time, volatile customer demand and one‑off engineered systems make it easy to over‑buy custom or semi‑custom control gear. AMtec’s case study on excess power distribution boxes in capital equipment is a good example. Once the design changes, those assemblies cannot simply be returned to the supplier and are often treated as sunk cost.

Put bluntly, the combination of conservative maintenance culture, long equipment lifecycles, and short component lifecycles almost guarantees that your plant will be sitting on obsolete PLC inventory unless you deliberately manage it.

Traditional Ways to Deal with Obsolete Automation Hardware

Most plants fall back on a familiar playbook when they finally confront obsolete PLC shelves. Accounting and logistics case studies outline the same options, whether the stock is electronics, mechanical assemblies, or general industrial inventory.

One option is retrofitting or reconfiguring assemblies to current requirements. AMtec defines retrofitting as modifying existing electro‑mechanical products, such as industrial controls and power distribution boxes, into a new configuration that meets current needs. They offer a simple screening rule: if roughly 80% or more of the materials, including the enclosure, match the new requirement, a full retrofit is likely technically and economically viable. In their 2019 case, reconfiguring six excess power boxes into a new configuration cost only about 16% of buying new units and cut lead time from 8 weeks to 2 weeks. For some PLC panels, a similar approach can turn “obsolete” enclosures into current standard builds by replacing only CPUs and critical modules.

If full retrofit does not pencil out, AMtec recommends harvesting valuable components from obsolete assemblies, focusing on long‑lead, high‑value, or critical parts that still appear in current designs. In PLC terms, this can mean reclaiming terminal blocks, power supplies, standard I/O modules, or network hardware, even if the CPU is no longer approved. The economics depend on the cost and safety risk of dismantling versus the value of recovered components, but benefits include space savings and reduced future material spend.

When reuse is limited, general excess stock guides such as Deandorton, Katana, Nest Egg, and SCMDOJO lay out a spectrum of disposition tactics. Companies return what they can to suppliers for credit, repurpose materials into new products, bundle slow movers into promotions, trade with partners, liquidate in bulk to closeout buyers, auction items directly, or in the end donate, recycle, or scrap. Finale Inventory notes that leading firms aim to keep excess and obsolete inventory below about 3% of total inventory value by using these levers proactively and tracking the financial impact.

All of this applies to PLC hardware, but with two additional complications. First, there is a real risk of downtime if you strip too many legacy spares and then have a failure before upgrade. Second, counterfeits and untested modules present very real safety and reliability issues, as Industrial Automation Co makes clear. That is where structured PLC buyback services can add value, if you use them carefully and in combination with retrofit and harvest options.

What a PLC Buyback Service Actually Is

Buyback programs are nothing new in other asset categories. Workwize describes IT equipment buyback programs where organizations sell outdated laptops, servers, and network gear to recover value, free storage space, and reduce e‑waste. DRex Electronics outlines high‑value buyback programs for surplus electronic components used by OEMs, contract manufacturers, and distributors. Both emphasize the same core idea: instead of letting surplus sit and depreciate, use specialist buyers to convert it into cash or credit.

In industrial automation, surplus and asset recovery programs play the same role for PLCs, drives, and related hardware. Industrial Automation Co mentions buybacks for Allen‑Bradley drives, FANUC amplifiers, and ABB modules as examples of monetizing idle stock while supporting a circular economy.

At a practical level, a PLC buyback service is a structured channel where you sell surplus or obsolete automation hardware to a specialist who then tests, refurbishes, and resells it into the secondary market. In some cases they buy outright. In other cases they take your stock on consignment, sell it over time, and share the proceeds. DRex’s model for electronic components illustrates both options clearly: direct sale for immediate cash, and consignment for higher potential return on slower‑moving items.

Automation‑focused buyback programs borrow heavily from the IT and electronics world. Workwize describes a typical IT buyback process where you inventory assets, request quotes, ship or arrange pickup, the vendor performs certified data destruction and testing, then finalizes valuation and issues payment or credit. DRex adds the emphasis on date‑coded components and shelf life: time matters, because the resale value of electronic components falls as they age. Reusely’s coverage of automated buyback platforms goes further, highlighting systems that automate pricing, inventory management, and communication so buybacks can scale from dozens to thousands of units with consistent control.

The same pattern applies to PLCs. The service is not just about writing a check for a pallet of old hardware. When done well, it bundles inventory analysis, price setting, functional testing, anti‑counterfeit controls, documentation, logistics, and in many cases reporting to support your ESG and compliance goals.

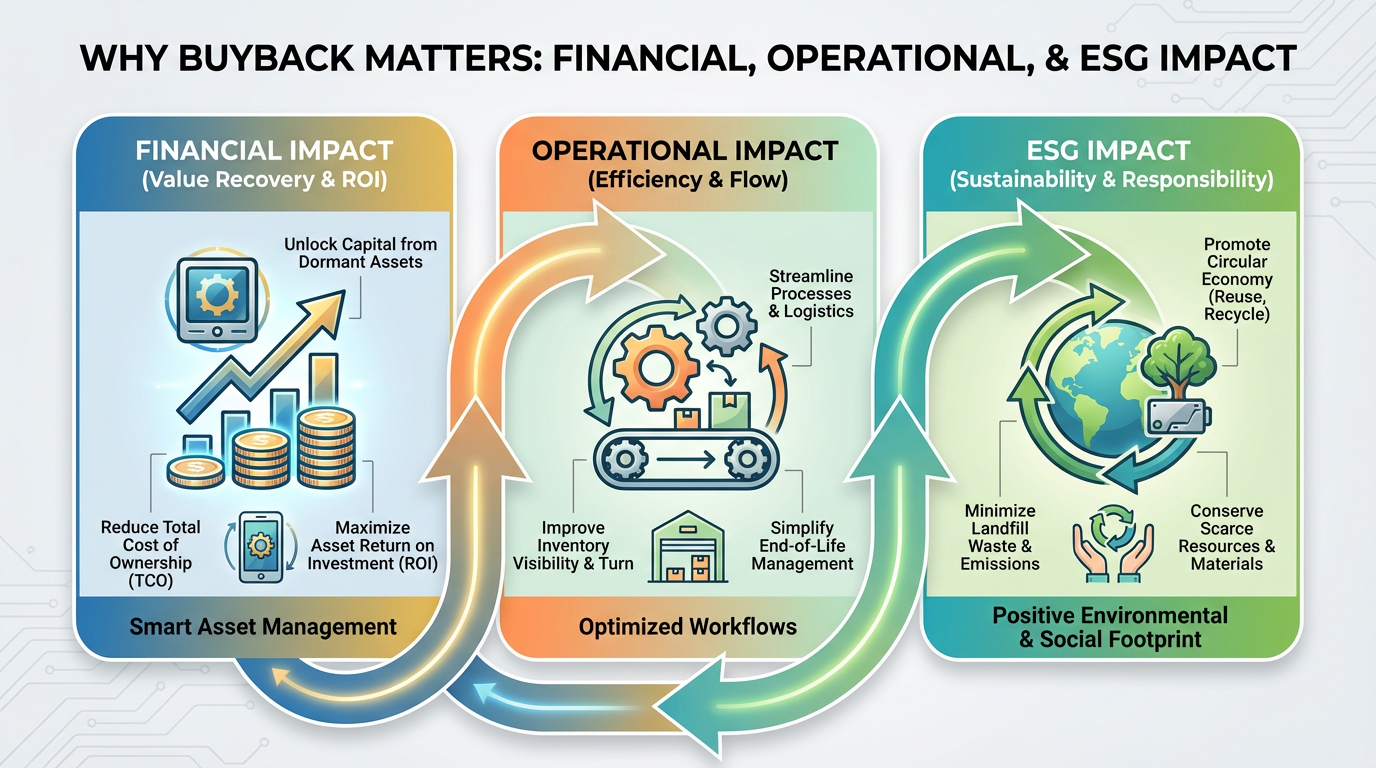

Why Buyback Matters: Financial, Operational, and ESG Impact

From the financial side, Finale Inventory points out that carrying dead stock at $100,000 can easily cost $20,000 to $30,000 each year in holding costs alone. Add write‑downs and write‑offs when auditors require you to mark inventory down to the lower of cost or market value, and the real cost of ignoring obsolete PLC shelves becomes clear. Buyback services let you convert some of that theoretical value into actual cash or credit, even if the recovery is well below book cost.

Operationally, clearing obsolete PLCs also makes spares management cleaner. Inventory case studies from Numerical Insights describe manufacturers sitting on large surpluses of obsolete components while being short of the parts required to keep their best‑selling products in stock. Many of us have seen the automation version of this: racks full of obsolete racks and processors while you are constantly expediting a small set of current safety I/O modules. A structured buyback program, combined with good forecasting and ABC analysis as recommended by nVentic and SCMDOJO, pushes you toward a smaller, more critical spare pool and away from random collections of “maybe useful someday” hardware.

There is a sustainability angle as well. Reusely cites the UN Global E‑Waste Monitor’s estimate that in 2019 the world generated about 53.6 million metric tons of e‑waste, roughly 59 million short tons, and only about 17.4% was properly recycled. Workwize notes that by 2022 the volume had climbed to roughly 62 million metric tons, on the order of 68 million short tons, with only about 22% recycled correctly. A single reused laptop can avoid energy and emissions equivalent to roughly 10 metric tons, or about 11 short tons, of carbon dioxide. While PLC racks are a smaller niche in that global picture, structured buyback and reuse is one of the few levers plants have to keep automation hardware out of landfills while still making rational financial decisions.

When you put those pieces together, buyback for obsolete PLC inventory becomes more than “selling a few old CPUs.” It becomes one instrument in a broader obsolescence strategy that improves your P&L, simplifies operations, and gives you a defensible environmental story.

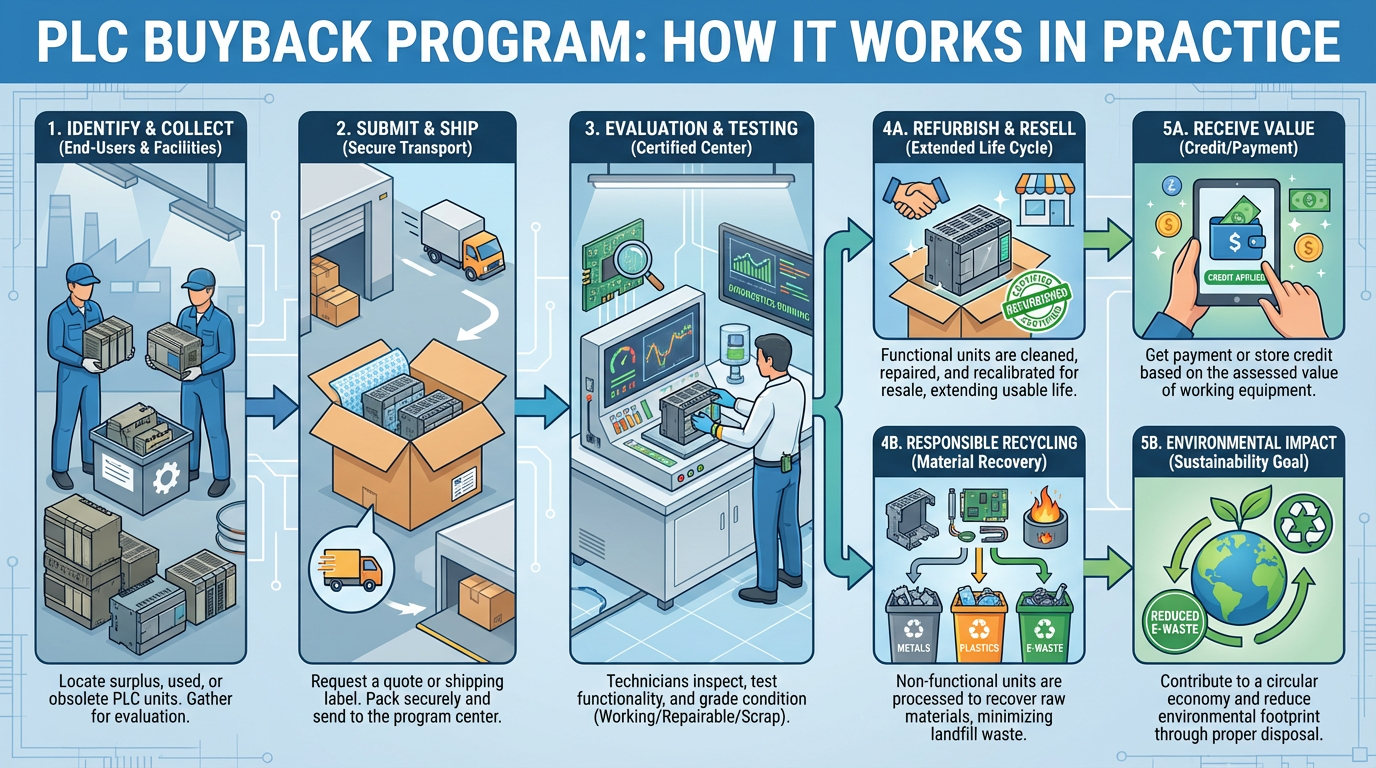

How a PLC Buyback Program Works in Practice

When I work with clients on monetizing legacy automation inventory, the actual workflow ends up looking very similar to the IT and electronic component programs described by Workwize and DRex, but with PLC‑specific twists.

The effort starts with a detailed audit of what you actually have. Industrial Automation Co recommends that plants audit their production lines to record part and serial numbers, firmware or configuration details, installation dates, maintenance history, and OEM‑stated lifespans. The same level of discipline should apply to the PLC spares cabinet you want to sell. A credible buyback quote depends on a clean list that captures manufacturer, family, catalog number, firmware revision if applicable, hardware series, physical condition, packaging status, and quantity.

The second stage is defining scope and priorities internally. Inventory and finance guidance from Finale, Katana, and Nest Egg all emphasize the importance of distinguishing excess from obsolete, and high‑value from low‑value stock. In a PLC context, that means pulling out truly critical legacy spares that you still need for lines that will remain in service for years, separating those from hardware associated with assets you have already retired, and identifying gear tied to transitions that are underway.

Once you know what you are prepared to sell, you request preliminary quotes. DRex’s guide to high‑value buyback programs highlights the importance of choosing the right buyer: look for ISO 9001 certified processes, global market reach, strong understanding of traceability and compliance, and flexible options including cash offers, consignment, or trade‑in credit. Workwize’s vendor selection checklist in the IT space adds relevant certifications such as R2 or e‑Stewards, environmental certifications such as ISO 14001, documented data sanitization processes, serialized reporting, and transparent pricing. The details differ for PLCs, but the principle is similar: treat this like any other strategic sourcing decision, not a one‑off fire sale.

After a buyer has confirmed interest and indicative pricing, you align on the sales model. Direct sale converts stock into immediate cash, which is useful when you need short‑term liquidity or want clean accounting lines. Consignment trades speed for higher potential recovery; this approach is better when you have larger volumes of slower‑moving legacy PLC hardware and can wait for the buyer to place it through global channels. Trade‑in credit against new automation purchases is effectively a structured discount and can work well when you are standardizing on specific platforms.

Logistics and testing come next. Industrial Automation Co stresses the need for multi‑point functional testing and robust warranties in the obsolete automation market, pointing to 24‑month warranties and comprehensive load and functional tests as benchmarks. A serious PLC buyback partner should be able to describe their test procedures, provide sample reports, and explain how they screen for counterfeits. Workwize also emphasizes data destruction and secure handling for IT assets; in PLCs and smart devices, that extends to clearing configurations, network parameters, and recipes where appropriate, or at least handling them under your plant’s security policies.

Finally, the buyer finalizes valuation and issues payment or credit. Workwize suggests that typical IT buyback cycles run in the range of 2 to 4 weeks from shipment to payment, with quotes often turned around in a week or less. PLC hardware follows the same pattern, although lead times can stretch when specialized testing is required or when shipments span multiple sites.

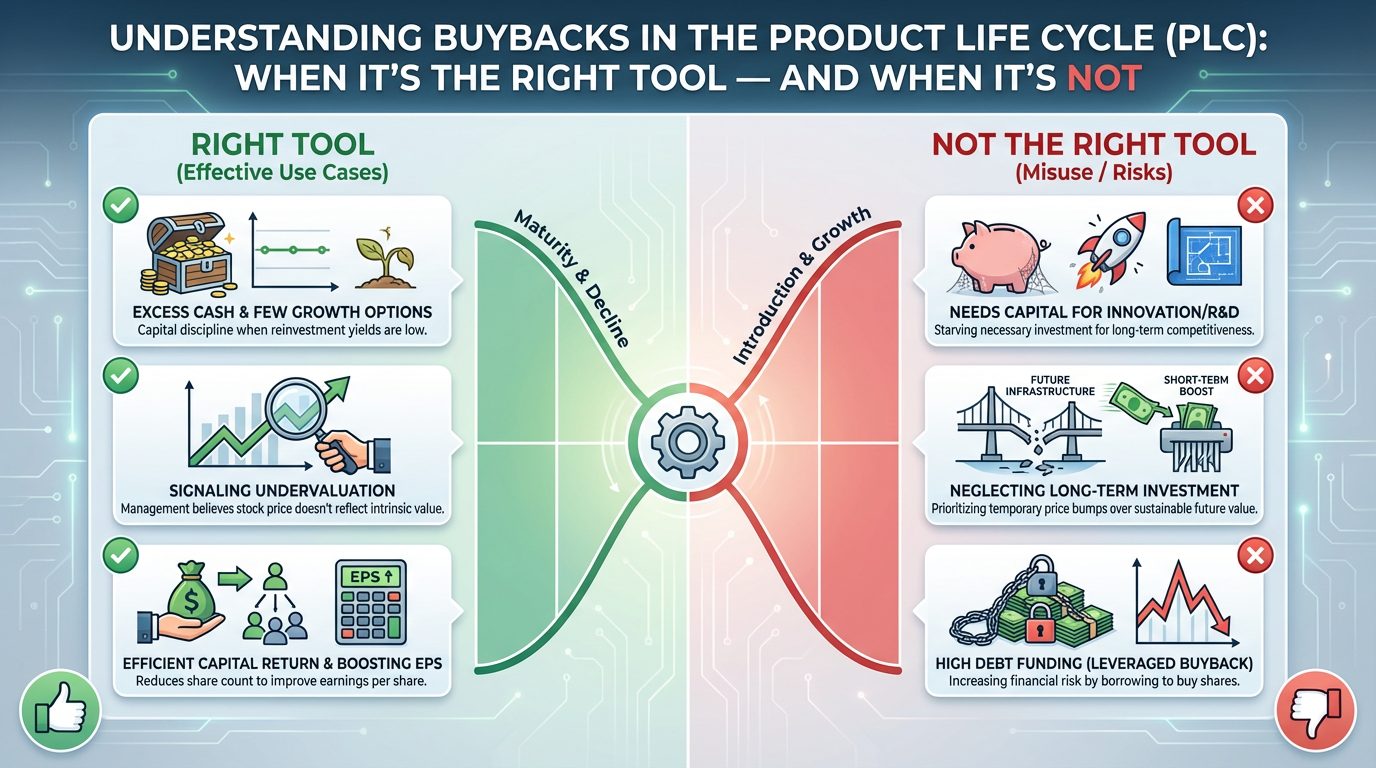

When Buyback Is the Right Tool for PLCs—and When It Is Not

Buyback is powerful, but it is not automatically the best path for every piece of obsolete PLC gear. Combining guidance from AMtec, Finale, Numerical Insights, and the remanufacturing literature gives a practical decision framework.

Buyback is usually a strong fit when you hold significant quantities of a legacy PLC platform that no longer appears in your internal standards but still has an active global installed base. That might include CPUs, standard I/O, communication cards, and drives from major brands that have gone end‑of‑life but remain deployed across many plants. DRex notes that components from leading semiconductor brands tend to be in especially high demand in secondary markets; the same logic holds for well‑known PLC families and servo platforms that remain common in the field.

Retrofit or reconfiguration is often a better path when an obsolete control assembly is still fundamentally aligned with your current requirements. AMtec’s 80% rule is a practical screen: if roughly four‑fifths of the materials match what you would design today, consider reworking the panel rather than selling it into the secondary market. The case where reconfiguration cost only 16% of new builds, with a reduction in lead time from 8 weeks to 2 weeks, illustrates how powerful that route can be.

Harvesting components makes sense when the assemblies are no longer economically retrofit‑worthy but contain high‑value parts that remain standard. Finale and AMtec both stress that the decision should consider dismantling and test costs versus the value of recovered parts, as well as warehouse space and future material spend. In PLC terms, this often means keeping power supplies, I/O modules, and standard terminal hardware while letting CPUs and older communications hardware go through buyback or scrap.

Complete write‑off and disposal remains the last resort. Finale’s accounting guidance describes how companies record write‑downs and write‑offs, along with the tax and audit implications. SCMDOJO and Nest Egg emphasize that you sometimes have to accept a full loss when there is effectively zero demand and no reasonable resale prospect. In an automation environment, that might be niche PLC gear for a process you will never run again and that has no active market.

The key is to treat buyback as one instrument in a toolkit, not a universal solution. A simple classification that separates critical legacy spares, retrofit candidates, harvest candidates, buyback candidates, and scrap can bring discipline to what otherwise feels like a once‑a‑decade clean‑up project.

Choosing the Right Buyback Partner for PLC Inventory

A centralized, structured buyback program can either reduce your risk or increase it, depending on whom you trust with your legacy automation inventory. Industry guidance from Industrial Automation Co, Workwize, DRex, and Microchip‑style obsolescence playbooks all point to similar selection criteria, which apply very directly to PLCs.

You want strong technical automation expertise so the buyer understands PLC families, firmware issues, and compatibility nuances. PLC Automation Group points out that obsolete automation parts frequently create compatibility and safety concerns when integrated with newer systems. A buyer who does not understand those issues can mis‑grade your inventory, misrepresent it downstream, or create risk for end users.

You also want rigorous testing and warranty standards. Industrial Automation Co underscores that counterfeit and untested parts can cause additional downtime, safety issues, and even insurance problems. They point to comprehensive functional and load testing and multi‑month warranties, such as 24‑month coverage, as practical benchmarks. A serious buyback partner should be able to share test reports, explain their anti‑counterfeit program, and demonstrate that they quarantine and destroy failed or suspect units.

Third, look for quality, security, and environmental certifications. In the IT space, Workwize recommends R2 or e‑Stewards certifications, along with ISO 14001 and other standards, to ensure responsible recycling and secure data destruction. DRex explicitly calls out ISO 9001 certification in their component buyback programs. For PLC hardware, the exact mix of certifications may differ, but the principle stands: if a buyer is handling large volumes of industrial electronics and does not have documented quality and environmental management systems, that is a red flag.

Fourth, insist on transparent pricing and clear buyback structures. Research on buyback pricing in remanufacturing, such as the work summarized on ResearchGate, shows that there are economic lower and upper bounds for buyback prices that keep all parties engaged. The OEM or remanufacturer must earn enough margin to justify processing returns, while repair shops or sellers need enough incentive to send parts back rather than repair or scrap them locally. In industrial practice, that means you should expect explanations of how age, condition, demand, and test status affect offers, and you should compare outright purchase versus consignment versus trade‑in credits rather than accepting a single take‑it‑or‑leave‑it number.

Finally, check that the partner’s systems can actually handle your complexity. Reusely and R3UP describe how automated buyback platforms use real‑time inventory tracking, automated pricing, multi‑location management, alerts, and cross‑listing to manage high‑volume buybacks. For a multi‑site industrial business, the ability to track what you shipped, what passed testing, what sold, and what revenue or credit came back by part number and location is not a luxury; it is a requirement for auditability and internal trust in the process.

The following table captures the key dimensions to evaluate.

| Criterion | What to Look For | Why It Matters for PLC Inventory |

|---|---|---|

| Automation expertise | Demonstrated knowledge of PLCs, drives, HMIs, typical failure modes | Reduces mis‑grading, avoids unsafe reuse, improves pricing accuracy |

| Testing and warranties | Documented functional and load testing, multi‑month warranties | Controls counterfeit risk and protects your reputation |

| Quality and environmental systems | Certifications such as ISO 9001 and ISO 14001, structured recycling | Supports ESG reporting and regulatory compliance |

| Pricing transparency | Clear explanation of price drivers and options (cash, consignment, credit) | Helps you optimize between immediate cash and higher long‑term recovery |

| Traceability and reporting | Serialized tracking, detailed settlement reports, audit‑ready records | Aligns with accounting guidance and internal control requirements |

| Logistics and scalability | Ability to handle multi‑site pickups, bulk shipments, and large lots | Makes buyback an ongoing program instead of a one‑time clean‑up |

Pricing Strategy: Getting Fair Value for Obsolete PLCs

In remanufacturing, buyback price is essentially the unit payment that encourages someone to send a part back instead of repairing or scrapping it locally. The analytical work summarized on ResearchGate shows that there are lower and upper bounds on that price for each player. If the price is too low, independent repair shops or plant maintenance teams will simply repair, reuse, or scrap parts themselves. If it is too high, the remanufacturer’s margin erodes and the whole program becomes uneconomic.

For PLC inventory, the same logic applies, but with additional drivers. DRex emphasizes that date‑coded components have limited shelf life and that the sooner you sell, the higher your likely return. Finale Inventory notes that items that have aged out to 180 days or more without movement often belong in the “likely obsolete” or “red risk” category, and that aging dashboards should flag these for action. Nest Egg and SCMDOJO both stress the importance of early detection, so you can discount and remarket before stock becomes truly dead.

Practically, you will get the best results if you segment your PLC inventory before you negotiate. Inventory optimization guides from nVentic and SCMDOJO recommend ABC analysis by value and velocity, and sometimes XYZ analysis by variability. Applying that thinking, you might group obsolete PLC items into high‑value, high‑demand modules; mid‑value but slower‑moving gear; and tail‑end oddities. High‑value items with an active market are good candidates for more aggressive negotiation, consignment, or even multiple bids. Low‑value or very slow‑moving items are better candidates for fast liquidation or inclusion in mixed lots, because the transaction cost of optimizing each unit exceeds the potential benefit.

It is also worth aligning internally on your objective function before you go to market. Finale’s guidance makes it clear that reducing the absolute level and percentage of E&O on the balance sheet can be just as important as maximizing unit recovery value. Many plants decide that the goal is to reduce obsolete PLC inventory to below a given percentage of total stock over a fixed horizon, accepting that they will sometimes trade a lower price for faster and more certain removal. Having that discussion up front makes buyback pricing decisions less contentious later.

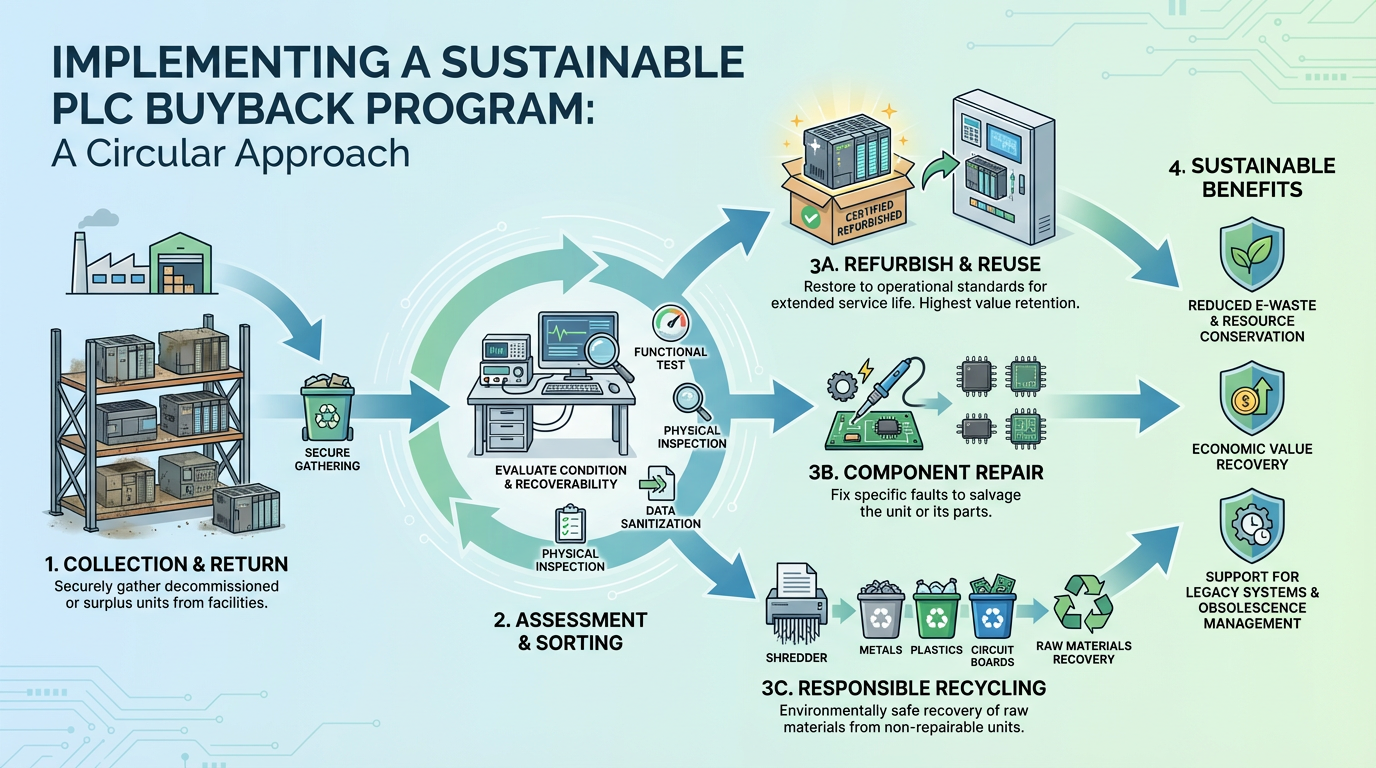

Implementing a Sustainable PLC Buyback Program

The companies that manage obsolete inventory well rarely treat buyback as a one‑time event. Instead, they integrate it into a broader obsolescence management program of the kind described in Microchip‑style playbooks, nVentic’s guide to reducing E&O, and the case studies from Establish and Numerical Insights.

The starting point is high‑quality data and visibility. nVentic emphasizes basic inventory hygiene: disciplined booking in and out of stock, regular physical or cycle counts, and a willingness to clear truly obsolete items rather than letting them sit. Finale and SCMDOJO recommend robust inventory management tools, clear policies on reorder points and safety stock, and frequent review cycles to catch items trending toward obsolescence. In automation, this means maintaining accurate records of PLC hardware not only in service but also in storage, and ensuring that version, series, and firmware details are captured so you can make informed disposition decisions.

Next comes lifecycle sensitivity and cross‑functional communication. nVentic highlights product lifecycle mismanagement as a major driver of excess and obsolete inventory, especially when optimistic sales forecasts drive initial overproduction or when end‑of‑life transitions are poorly planned. For PLCs, that maps directly onto how you respond to OEM end‑of‑life notices from suppliers such as Rockwell Automation or Siemens. Plants that avoid large piles of obsolete spares typically coordinate engineering, maintenance, supply chain, and finance around the timing of migrations, last‑time buys, and stockpiling for long‑lived lines.

With that foundation in place, you can formalize a decision flow for legacy PLCs. Items that are still needed as critical spares for long‑lived assets remain in controlled stock, with explicit service‑level targets informed by nVentic’s recommendations on differentiated service levels. Assemblies that meet AMtec’s 80% retrofit rule are evaluated for reconfiguration. Modules that remain standard but are overstocked become internal redeployment candidates or buyback candidates, depending on demand across your network. Truly obsolete items that have no internal use and weak market appeal move toward liquidation, donation, recycling, or write‑off, following the structured monetization and disposal playbooks described by Finale and SCMDOJO.

Automated buyback platforms, as described by Reusely and R3UP, can support this programmatic approach. They bring automated pricing, real‑time inventory updates, multi‑location tracking, and reporting capabilities that make it feasible to run small but continuous buyback waves instead of waiting for the next warehouse clean‑up crisis. Used correctly, they also free your internal teams to focus on higher‑value work such as planning migrations and optimizing spare strategies rather than manually pushing spreadsheets.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

There are a few recurring mistakes that undermine PLC buyback and obsolescence efforts.

One is treating buyback as an excuse to offload safety‑critical items without proper control. Industrial Automation Co warns that counterfeit or untested parts can introduce serious safety risks and additional downtime. If you send untested safety PLCs, safety I/O, or motion controllers into the secondary market without ensuring that your buyer has robust testing and quality systems, you are effectively exporting risk to someone else’s plant and possibly damaging your own reputation.

Another is focusing purely on price while ignoring governance and accounting. Finale’s discussion of GAAP treatment for obsolete inventory makes clear that you need solid documentation of what you disposed of, how, when, and for how much. The same is true for tax deductions, especially when donation or recycling is involved. If your buyback partner cannot provide serialized asset reports and destruction or resale documentation, your finance team will struggle to reconcile the books and defend their positions in audits.

A third pitfall is waiting too long. Nest Egg and SCMDOJO both stress that early detection and action are essential. Items that sit untouched for long periods move from slow‑moving to obsolete, and options narrow from discounting and remarketing to liquidation and scrap. For PLCs, that pattern is even sharper because of firmware obsolescence, changes in safety standards, and increasing counterfeit risk as original OEM production ends. Acting while a platform is still actively supported or at least widely deployed yields both better prices and better partner options.

Finally, some organizations neglect the production‑line side of the obsolescence equation while focusing only on the warehouse. Industrial Automation Co emphasizes that auditing the installed base and monitoring manufacturer end‑of‑life notices are essential to avoid being trapped without spare options. A buyback program that clears obsolete PLC shelves but ignores the fact that several running lines are one failure away from long unplanned downtime is not good obsolescence management; it is just short‑term cash optimization.

FAQ

How do I decide how many legacy PLC spares to keep versus sell?

Inventory experts such as nVentic and Finale recommend differentiating service levels by item based on business criticality. In practice, that means keeping a buffer of high‑risk, hard‑to‑replace obsolete parts that support assets you plan to run for years, while moving non‑critical duplicates and spares tied to retired processes into your buyback or liquidation pipeline. A joint review between maintenance, engineering, and finance is the best way to set those thresholds.

What information should I gather before approaching a PLC buyback partner?

The more complete your data, the better your quotes. Following the audit guidance from Industrial Automation Co and DRex, you should compile manufacturer names, catalog or part numbers, series and firmware revisions where relevant, quantities, packaging status, visible condition, and any available test or maintenance history. Grouping items by platform or family also helps buyers quickly assess demand and streamline their own resale planning.

Can buyback programs support reliability, or do they only monetize dead stock?

When integrated into a broader obsolescence strategy, buyback can actually support reliability. By converting truly obsolete or non‑standard PLC inventory into cash or credit, you can fund migrations, purchase current‑generation spares with full OEM support, and clean up confusing spare pools that lead to mis‑applied parts. The key is to protect a well‑justified core of critical legacy spares while aggressively monetizing everything outside that core.

In the end, buyback services for obsolete PLC inventory are not a silver bullet, but in the hands of a disciplined operations team and a trusted technical partner they turn dust‑covered shelves into useful capital, simplify your spare strategy, and help close the loop on an often‑ignored part of the automation lifecycle.

References

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297653213_Selection_of_buyback_price_for_OEM_for_efficient_spare_parts_management_in_remanufacturing_business

- https://www.establishinc.com/inventory-management

- http://ehx.lny.mybluehost.me/excess-obsolete-inventory-management-strategies

- https://amtec1.com/mini-case-study-reduce-excess-and-obsolescence/

- https://deandorton.com/ten-ways-to-deal-with-excess-inventory/

- https://www.finaleinventory.com/accounting-and-inventory-software/obsolete-inventory

- https://www.goworkwize.com/blog/it-asset-buyback-program

- https://www.icdrex.com/inventory-to-income-a-guide-to-high-value-buyback-of-surplus-electronic-parts/

- https://itemit.com/managing-obsolete-inventory/

- https://katanamrp.com/obsolete-inventory/

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment