-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Certified Pre-Owned Industrial Drives: Quality and Value

Why Certified Pre-Owned Drives Belong in Your Strategy

Every plant manager eventually faces the same unpleasant spreadsheet: new drives on one side, shrinking capital budget on the other, and a line of aging VFDs, servos, and soft starters that have already given you more than their fair share of nuisance trips.

New hardware is the easy answer, but not always the right one. If you are running a brownfield facility, trying to stretch an existing line, or standardizing on a family of drives that is no longer current, you need a smarter approach than “replace everything with new.”

That is where certified pre-owned drives can earn their place.

The idea is not theory. In the automotive world, certified pre-owned programs are mature, data-driven, and heavily scrutinized by groups like U.S. News, AAA, and Consumer Reports. Those programs consistently show that when you combine disciplined inspection, defined standards, and a real warranty, you can turn late-model used assets into reliable, lower-risk options that cost far less than buying new.

This article borrows the proven structure of automotive certified pre-owned programs and applies the same thinking to industrial drives. The goal is simple: give you a practical framework to decide when certified pre-owned drives make sense, how to separate serious programs from marketing fluff, and how to protect your production lines when you choose the used route.

What “Certified Pre-Owned” Really Means

In consumer markets, a certified pre-owned vehicle is not just any used car with a detail job. U.S. News summaries, AAA guidance, and dealer program documentation converge on a consistent definition. A certified pre-owned vehicle is typically a late-model, low-mileage unit that meets strict age and usage limits, passes a multi‑point inspection, is reconditioned to the program’s standards, and is sold with a defined, limited warranty backed by the automaker or an authorized program owner.

The details vary by brand. Some programs use around a hundred inspection checks; others, like a well-known luxury manufacturer, cite more than three hundred and sixty inspection points plus a road test. Programs often combine the remainder of the original new-car warranty with added coverage. One luxury program highlighted by U.S. News layers two additional years of coverage with no mileage limit on top of the initial four-year warranty, and throws in services such as complimentary scheduled maintenance visits, loaner vehicles, roadside assistance, and trip-interruption support.

A few other consistent patterns stand out in the research. First, access is limited: only late-model, lightly used units qualify, and many programs lean heavily on lease returns because those vehicles tend to be well-maintained and within age and mileage caps. Second, the certification comes with a price premium compared with a regular used example, often on the order of about $1,000 to $3,000 according to dealer and retailer analyses, but still well below the price of a new unit. Third, independent testing by organizations such as Consumer Reports indicates that certified pre-owned cars, as a category, have fewer problems—about fourteen percent fewer issues than comparable non-certified used cars in one analysis—provided the underlying models are reliable.

When you strip away the automotive paint, what you are left with is a simple structure that transfers directly to industrial hardware. A “certified pre-owned drive,” as used in this article, should meet three non-negotiable principles. It should be a relatively recent, technically suitable model with known history and bounded usage. It should be subjected to a systematic inspection and refurbishment process tied to published criteria. And it should be sold with defined, written warranty and support terms backed by an identifiable party that is willing and able to stand behind that promise.

If any of those three pillars are missing, you are not looking at a certified pre-owned program.

You are just buying used parts with a marketing label.

Lessons from Automotive CPO Programs You Can Reuse

The automotive data gives you a benchmark for what a serious certified pre-owned program looks like. A few lessons translate especially well to industrial drives.

First, the credibility of the backing organization matters more than the sticker on the unit. AAA and other consumer advisers make a clear distinction between manufacturer-backed certified programs and dealer- or third‑party-only “certified” schemes. In the first case, the automaker sets uniform standards, oversees inspections, and honors warranties across its network. In the second, the coverage and rigor can be much thinner, and support may be limited to a single location.

Second, the inspection must be systematic and documented, not just a quick functional test. Automotive programs commonly advertise inspection checklists covering one hundred to two hundred items, including engine, transmission, brakes, steering, suspension, body, and electronic systems. Some luxury programs go even further. Items that do not meet standard are either replaced or the vehicle is rejected.

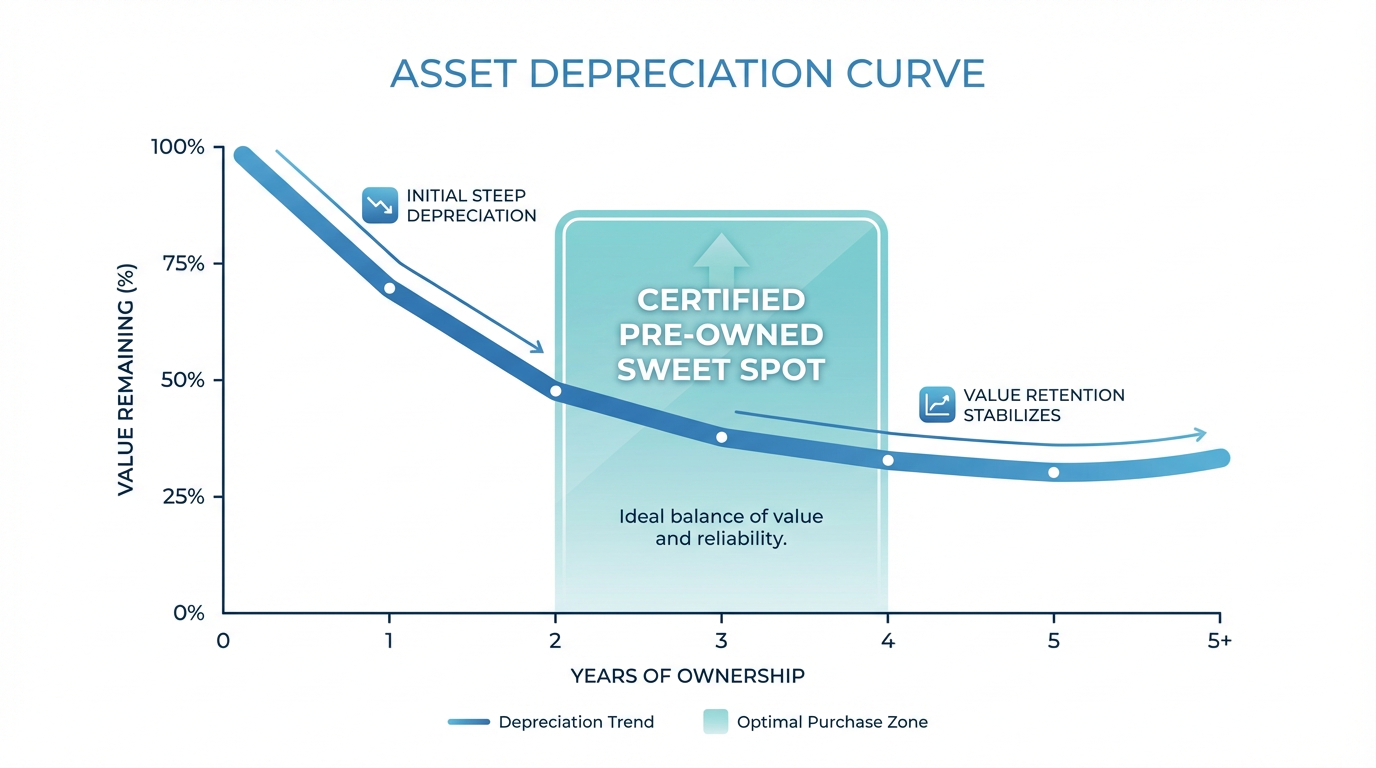

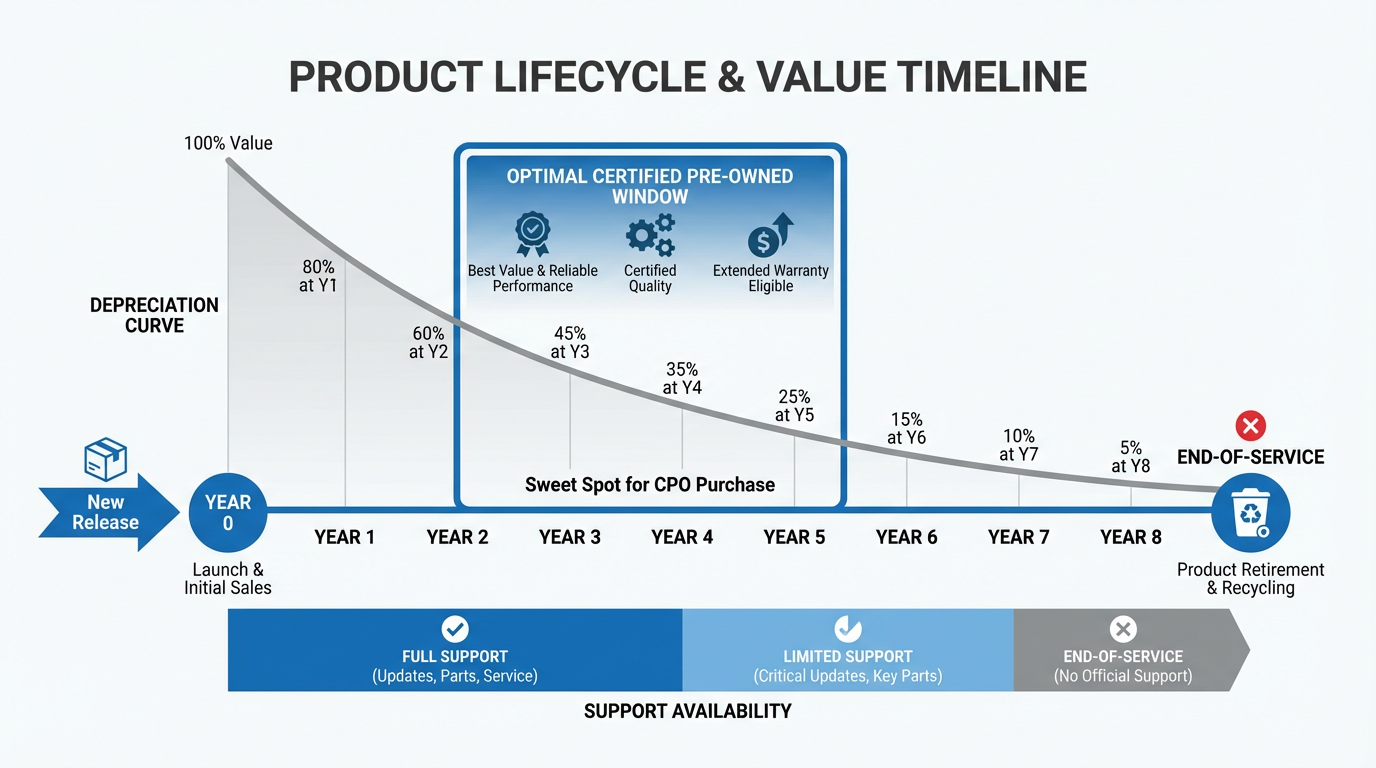

Third, depreciation is your friend if you manage it correctly. Industry data compiled in sources like AAA and U.S. News shows that many new cars lose roughly twenty to thirty percent of their value in the first year, and around thirty percent by the end of year two. That is why two- to three-year-old certified pre-owned vehicles can deliver substantial savings while still being under warranty.

Fourth, the price premium needs to be judged against total cost of ownership. Dealer guidance and independent summaries point to typical certified pre-owned car premiums of roughly $1,000 to $3,000 over similar non-certified used cars. However, that premium effectively pre-pays for inspection, reconditioning, and warranty, and can be offset by fewer large repairs and stronger resale value.

Finally, transparency and third-party validation still matter even in certified programs. AAA and other experts still recommend reviewing the vehicle history report and, in many cases, having an independent mechanic perform a pre-purchase inspection, especially when you are dealing with dealer- or third‑party certification rather than factory-backed programs.

The direct data behind those points comes from cars, not drives.

But the underlying ideas are universal. You want a credible backer, a repeatable inspection and refurbishment process, leverage of early-life depreciation, a realistic view of total cost of ownership, and enough transparency that you are not buying a polished unknown.

Translating Certification Discipline to Industrial Drives

Industrial drives are not cars. They live in hotter environments, deal with harmonics, dust, vibration, and curious electricians, and they typically sit bolted to a panel instead of rolling down the highway. But the core risks and levers are similar: unknown history, hidden wear, software and configuration drift, and potentially high costs if a failure stops production.

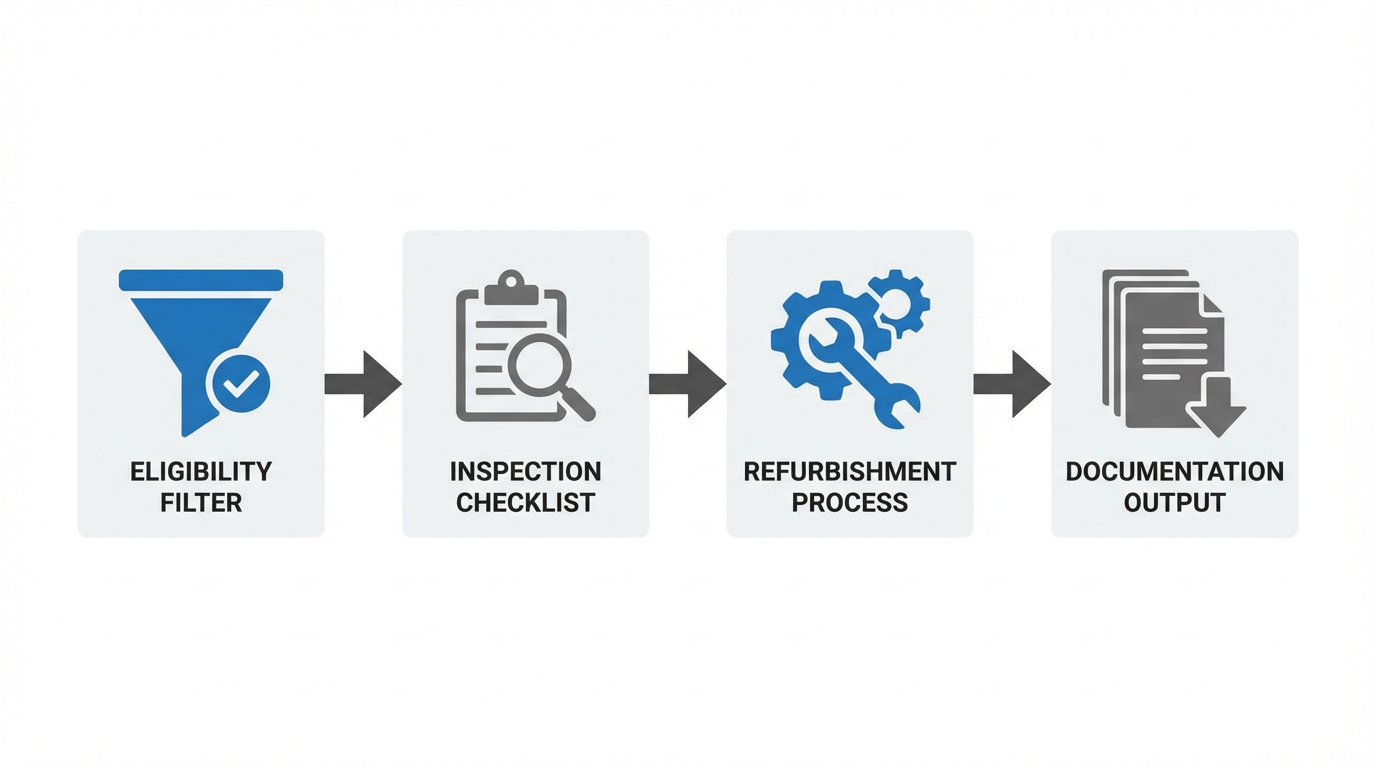

When you adapt the certified pre-owned concept to drives, you are not copying automotive checklists point for point. You are borrowing the discipline. In practice, a robust certified pre-owned approach for drives should cover four areas: eligibility, inspection and testing, refurbishment, and documentation.

Eligibility is where you decide which models and histories you are willing to trust. Automotive programs restrict age and mileage. For drives, the equivalent filters include model families that are still supported by the manufacturer, firmware that can be brought current, and operating histories that are compatible with your risk appetite. You may, for example, set internal rules that only drives from climate-controlled environments, or drives with known maintenance records, qualify for your certified stream. You may also exclude units that have had certain types of failures, such as catastrophic short circuits on the DC bus. The point is not that there is one correct threshold, but that you have defined thresholds at all.

Inspection and testing is where the real quality work happens. The automotive analogy is a multi-point inspection of engine, transmission, brakes, and so on. For drives, that translates into structured checks of major assemblies and known wear points: power semiconductors, DC link capacitors, cooling paths and fans, input and output terminals, control boards, encoders or feedback interfaces, parameter storage, and protective functions. A meaningful program exercises the drive electrically under load, verifies thermal behavior and protective trips, and checks for nuisance conditions like excessive carrier noise or control instability. A quick power-on check is not enough.

Refurbishment is where you decide what gets proactively replaced or reworked. Automotive certified programs routinely replace tires, brake components, and other wear items. With drives, this is the stage for replacing cooling fans, aging capacitors, filters, and damaged connectors, cleaning or replacing heat sinks, updating firmware to a supported revision, and resetting or documenting critical parameters. Refurbishment should be driven by documented criteria, not by what happens to be in the parts bin that day.

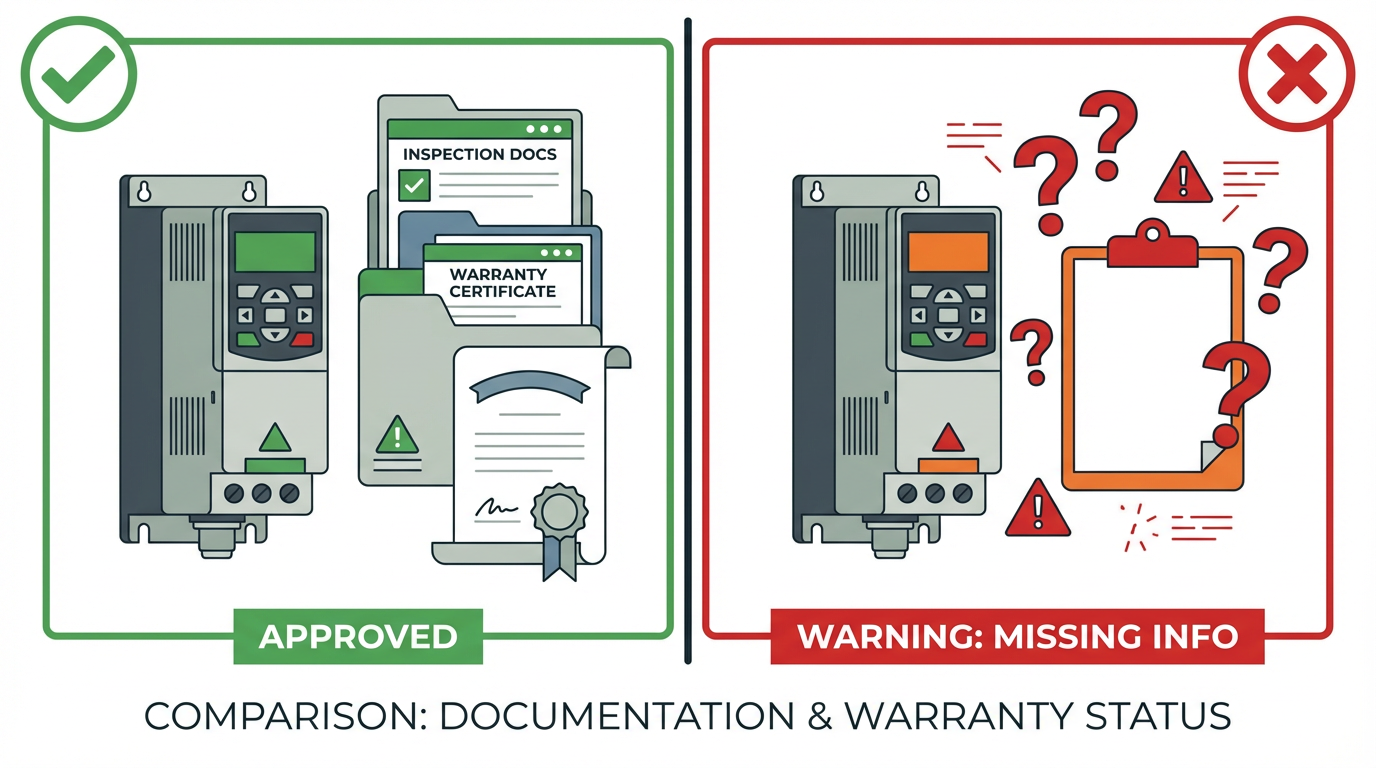

Documentation is the final step that turns a refurbished unit into a certified one. Automotive programs provide written inspection forms, warranty booklets, and vehicle history reports. For drives, you should expect at least a test record that lists what was checked and under what conditions, a summary of parts replaced or reworked, baseline measurements such as insulation resistance where relevant, and clear warranty terms that describe coverage, exclusions, and claim process.

When those four elements are explicit and repeatable, certified pre-owned stops being a buzzword and becomes a quality system you can actually manage.

New vs Certified Pre-Owned vs Plain Used Drives

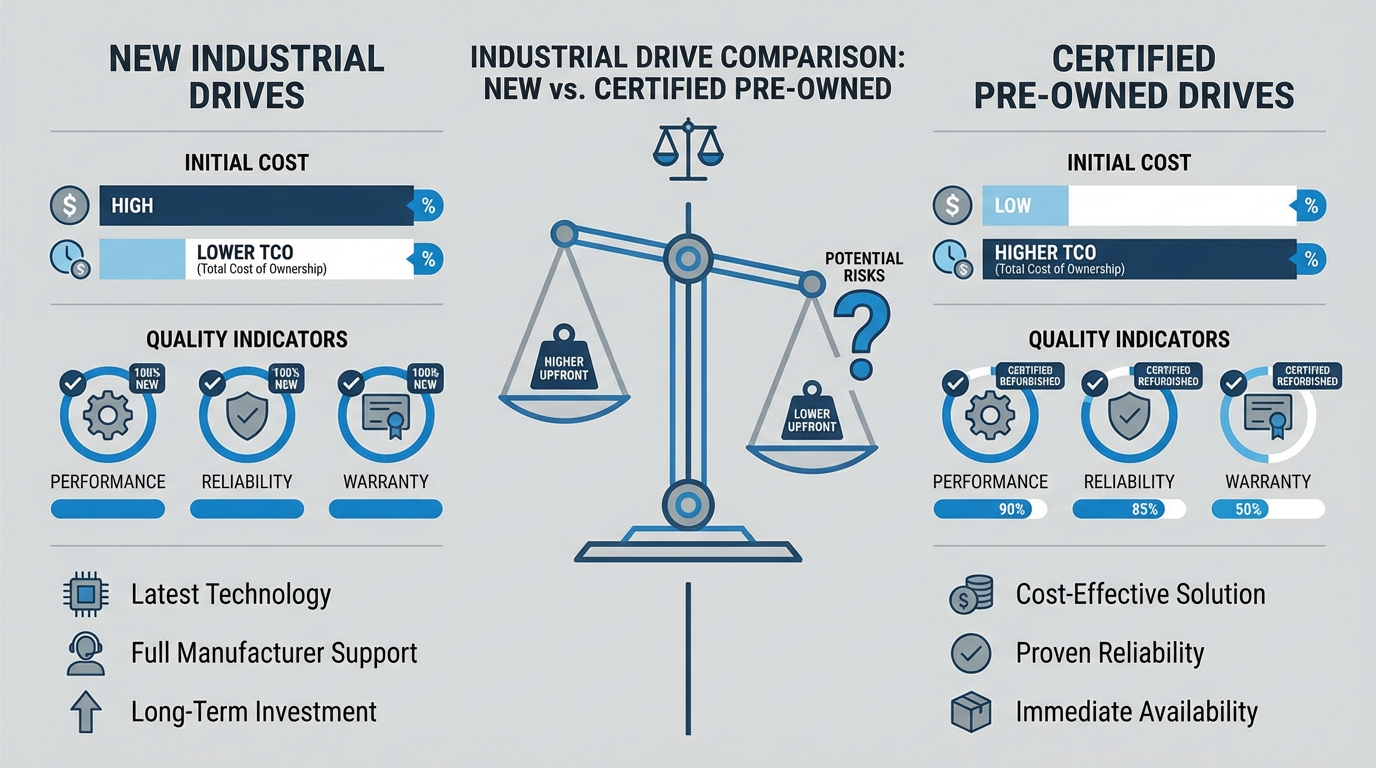

It is sometimes easier to think in trade-offs than definitions. New drives, certified pre-owned drives, and plain used drives each sit in a different place on the cost–risk spectrum.

You can frame the comparison conceptually as follows:

| Option | Upfront Cost | Condition And Testing | Warranty And Support | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New drive | Highest | Factory new, fully tested by OEM | Full new-product warranty and OEM support | Greenfield projects, long design horizons |

| Certified pre-owned drive | Moderate, lower than new | Late-model, systematically inspected and refurbished | Limited but defined warranty from OEM or qualified program owner | Brownfield upgrades, cost-constrained expansions |

| Plain used or “as-is” drive | Lowest sticker price | Unknown or minimally checked; often only powered up | Little to no warranty; buyer carries failure risk | Emergency spares, non-critical experiments |

This table is conceptual rather than statistical. For monetary context, you can look back to the automotive world, where certified pre-owned vehicles almost always cost more than non-certified used examples but significantly less than brand-new cars. Dealer data and retail analysis typically place the certified pre-owned premium in the low thousands of dollars, while still benefiting from the twenty to thirty percent depreciation that many vehicles suffer in the first one to two years. Certified buyers pay extra for inspection, reconditioning, and warranty, but they dodge the steepest part of new-car depreciation.

The direct price curves for drives will differ, but the forces are similar. New drives carry full manufacturer warranty and the highest price. Plain used drives have the lowest sticker price but push more risk onto you. Certified pre-owned drives sit between those extremes, trading a higher upfront cost than “as-is” units for reduced technical risk and predictable support.

Managing Risk And Total Cost Of Ownership

When you pitch certified pre-owned drives to finance or corporate leadership, you should avoid talking about unit price alone. Automotive research from AAA, Consumer Reports, and others repeatedly warns buyers not to judge certified pre-owned cars on sticker price alone, but to look at total cost of ownership: purchase price, financing cost, warranty coverage, expected repair costs, and even resale value. The same logic holds for drives.

On the cost side, certified pre-owned drives will usually be more expensive than plain surplus units from a broker or auction. That premium covers labor and parts to inspect and refurbish, diagnostic time, and the financial risk of warranty support. On the savings side, you reduce the likelihood of early-life failures, avoid some catastrophic failures that can damage motors or switchgear, and may shorten commissioning time because you are dealing with tested, known-good hardware. In some cases you also avoid or defer the cost of redesigning control panels, requalifying different drive families, or rewriting logic to match a new platform.

Automotive data helps frame how meaningful that trade-off can be. Consumer Reports found that certified pre-owned cars have around fourteen percent fewer problems than comparable non-certified used cars in its data set, and concluded that the premium is often worth paying, provided the base vehicle has good reliability. That number does not directly apply to drives, but it demonstrates that a structured certification process can measurably change failure rates. In an industrial context where a single line stoppage can cost many thousands of dollars per hour, even a modest reduction in failure probability can justify a significant premium on the drive itself.

Financing is another dimension. Many automotive certified pre-owned programs qualify for low interest rates closer to new-car offers, and lenders sometimes treat certified vehicles similarly to new ones for loan purposes. Industrial financing is more bespoke, but the principle remains: predictable quality and documented refurbishment make it easier for internal capital committees or external lenders to justify favorable terms, compared with taking collateral risk on a random lot of used hardware.

When you talk about total cost of ownership, frame certified pre-owned drives as part of a portfolio strategy. You still buy new hardware where lifecycle and support justify it. You still keep a few plain used units as emergency spares. Certified pre-owned sits between them, absorbing a large share of retrofit and expansion work where budget is tight but uptime is non-negotiable.

Spotting Real Certification Versus Marketing

Automotive buyers are warned constantly to distinguish between factory-backed certified programs and dealer-created or third‑party “certified” schemes that may offer weaker coverage. U.S. News and Consumer Reports both highlight that a quick test is to ask who backs the warranty and whether the certifying brand matches the vehicle’s brand and franchised dealer network.

The same skepticism serves you well in the drive market. When you evaluate a certified pre-owned drive offering, start with the backer. If the program is run by the original manufacturer or an authorized partner with documented access to genuine parts, firmware, and technical bulletins, your baseline confidence is higher. If the program is run by a small reseller with no formal relationship to the OEM and only a brief “tested good” statement on the quote, you should treat the certification as marketing until proven otherwise.

Next, ask to see the inspection and refurbishment checklist, not a brochure. Automotive programs talk about one hundred or more specific inspection points and spell out which components are in or out of scope. Some luxury programs highlight very detailed inspections, from engine internals to upholstery stitching, precisely to signal rigor. For drives, you should expect similar specificity: which boards are visually inspected, which electrical tests are conducted, what load profiles are used, which consumables are always replaced, and where units are rejected outright rather than patched.

Warranty terms deserve the same attention you would give a new drive warranty. Automotive guidance stresses reading the fine print: what components are covered, where coverage starts and ends in time and miles, what deductibles apply per claim, and whether the warranty is transferable. For drives, focus on what failures are covered and for how long, whether coverage is limited to repair or includes swap-out, who pays freight, and what conditions void the warranty. Be very wary of vague phrases like “limited warranty” with no written detail.

Finally, insist on documentation for each unit, not just the program in general. Automotive certified buyers are urged to review a vehicle history report and keep a copy of the inspection checklist. For drives, that translates into serial number–specific records: what was done, what firmware is loaded, what baseline measurements were taken. If a seller claims a drive is certified but cannot produce documentation tied to that serial number, you are effectively buying an ordinary used unit with a verbal assurance.

Practical Evaluation Approach For Plant Teams

Translating all of this into a plant-floor decision process, you can think in terms of a few straightforward questions that operations, maintenance, and engineering can walk through together.

One question is whether the candidate drive model is a good technical fit for your plant. That includes its voltage and current ratings, compatibility with your existing communications buses, and availability of spare parts and technical support from the OEM. Certified pre-owned status does not fix a poor platform choice. Automotive programs address a similar concern by limiting certification to models and years the manufacturer is prepared to support.

Another question is about vendor capability and incentives. In automotive guidance, prospective buyers are encouraged to weigh manufacturer-backed certified programs more heavily than dealer-only schemes because the automaker has reputational and financial skin in the game. In the drive world, look for evidence that the certifier has test infrastructure, access to OEM documentation, and enough volume that a bad batch would actually hurt them. A tiny broker that sells a handful of drives a year has limited incentive to invest in a robust process.

You should also discuss what level of risk reduction you actually need. For non-critical applications—temporary test rigs, low-consequence conveyors, and similar loads—a plain used drive with a basic functional test may be acceptable. For critical process drives whose failure stops a line or creates safety concerns, you want certification discipline that resembles automotive factory programs: strict eligibility, structured inspection, and meaningful warranty.

Internal communication matters as well. Finance needs to understand that a certified pre-owned drive will probably not be the cheapest line item on a quote, but may still be the lowest-cost option over a five-year window. Maintenance needs to know what baseline tests were performed so they can monitor units intelligently. Engineering needs to know firmware versions and configuration constraints so they do not inadvertently void warranties. Treat certified pre-owned drives as part of your asset management system, not as one-off bargains.

Risks, Traps, And When To Walk Away

Buying used hardware always carries some risk. Certified pre-owned programs are about managing, not eliminating, that risk. Automotive research highlights several traps that carry over directly to drives.

One trap is overpaying for a label that does not actually buy you much protection. Dealer-created “certified” car programs sometimes amount to little more than cosmetic preparation and a short, limited warranty. Consumer publications caution buyers to look past the word “certified” and focus on who backs the warranty and what it covers. For drives, if the certification does not come with documented inspection, real parts replacement, and written warranty, be skeptical of any price premium.

Another trap is assuming certification overrides the underlying platform’s reliability. Consumer Reports explicitly warns that some car models are unreliable regardless of certification; paying extra for a certified version of a fundamentally problem-prone vehicle may not make sense. The same is true for drives. If a specific series has known thermal or component issues in your environment, certification does not magically erase those design realities. In those cases, new hardware or a different platform may be safer, even if it costs more.

A third trap is neglecting independent verification. Automotive experts still recommend third-party pre-purchase inspections and reviewing vehicle history reports even for certified cars, especially when the certification is not factory-backed. In an industrial setting, you may not have the luxury of a full lab duplication for every drive, but you can at least perform baseline checks on arrival: visual inspection, insulation checks where appropriate, verification of nameplate and firmware, and alignment of supplied documentation with the unit you received. If there is a mismatch between paperwork and hardware, pause before installing.

Finally, do not ignore lifecycle and obsolescence. Automotive certified programs generally stay within a window of years where parts and service are widely available. For drives, you should avoid treating certification as a way to justify extending very old platforms indefinitely. If the OEM has announced end-of-service dates or stopped producing critical spares, even a nicely refurbished drive may leave you exposed in a few years. Certified pre-owned drives work best in the same age band where automotive certified vehicles shine: recent enough to be fully supportable, old enough that someone else has already borne the steepest depreciation.

Brief FAQ

Is a certified pre-owned drive always better than a new drive?

No. New drives still make the most sense when you are designing long-lived systems around current platforms, when you need the longest possible warranty, or when you rely heavily on the latest diagnostics and features that older models simply do not offer. Certified pre-owned shines when you are working with installed bases, retrofits, or constrained capital and want to reduce risk without paying new-drive prices.

How big a premium over plain used drives is reasonable?

Automotive data often cites certified pre-owned car premiums in the low thousands of dollars compared with similar non-certified used vehicles, and shows that buyers frequently recover that premium through fewer problems and better resale value. For drives, the right premium depends on the criticality of the application and the quality of the certification program. The key is to compare the premium with the potential cost of a failure in your specific process, not just with the price of the drive itself.

Do I still need to test a certified pre-owned drive when it arrives?

Yes. Certification reduces risk but does not remove your responsibility. Just as automotive experts still suggest independent inspections for certified cars in many cases, you should treat incoming certified drives as critical assets that deserve sanity checks and proper commissioning. At a minimum, verify identity, documentation, and basic electrical health before you rely on the unit for production.

Closing Thoughts

From a systems integration perspective, the value of certified pre-owned drives is simple: you are trying to buy down uncertainty. The automotive world has shown, with hard data and well-documented programs from sources like U.S. News, AAA, TrueCar, and Consumer Reports, that disciplined certified pre-owned structures can materially reduce failure rates and ownership surprises while keeping capital spending in check. If you bring the same discipline—clear eligibility rules, rigorous inspection, defined refurbishment, and real warranty—to industrial drives, you can turn used hardware from a gamble into a tool you deploy strategically for quality and value.

References

- https://www.asi.k-state.edu/doc/meat-science/selection-and-purchase-of-used.pdf

- https://farms.extension.wisc.edu/articles/used-tractors-can-make-work-easier-on-farms-and-large-properties/

- https://www.consumerreports.org/cars/the-truth-about-certified-pre-owned-cars-a8333898965/

- https://www.atchinson.net/blogs/7669/what-to-look-for-when-shopping-certified-pre-owned-vehicles

- https://www.gmcertified.com/certified-vs-used

- https://www.bismarckmotorcompany.com/benefits-of-certified-pre-owned/

- https://www.edmunds.com/car-buying/certified-pre-owned-cars-a-reality-check.html

- https://fastercapital.com/content/Vehicle-History-and-Certification--Certified-Pre-Owned--A-Strategic-Move-for-New-Entrepreneurs.html

- https://www.habberstadbmwofbayshore.com/cpo-explained-certified-pre-owned-vehicles/

- https://www.kbb.com/certified-pre-owned/

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment