-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Remanufactured VFD Quality Standards in the Automation Industry

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

Why Remanufactured VFDs Are Back in the Critical Path

If you run an industrial plant today, chances are a big share of your uptime and energy savings rides on variable frequency drives. VFDs sit on fans, pumps, conveyors, mixers, and process lines from the MCC all the way out to skids. When those drives fail, production stops, and you feel it immediately in lost throughput and maintenance overtime.

At the same time, OEMs keep sunsetting product lines while the machinery those drives control still has plenty of life left. That is why remanufactured and refurbished VFDs have moved from “last resort” to a deliberate strategy in many facilities. According to guidance from Industrial Automation Company, refurbished automation parts typically save about thirty to seventy percent compared with new hardware while keeping legacy systems running without expensive redesigns. Research cited in industry commentary from the University of Manchester suggests that refurbishing drives can be as much as ninety‑one percent more sustainable than buying new units, thanks to reduced material use and lower embodied energy.

As a systems integrator, I see three main drivers behind the shift toward remanufactured VFDs. First, budgets are tight, and a well‑rebuilt drive often recovers the original capital investment at a fraction of replacement cost. Second, lead times for new drives can stretch into weeks while a remanufactured unit can be on the floor and online in a matter of days. Third, swapping in a new family of drives can trigger a ripple of integration work: firmware mismatches, different communication cards, new parameter interfaces, and updated safety functions. When a remanufactured unit drops into the same footprint and I/O scheme, integration risk falls sharply.

None of that matters, however, if the remanufactured drive is unreliable. That is where quality standards come in: clear expectations for testing, components, documentation, and lifecycle support so that a remanufactured VFD behaves like a known quantity, not a gamble.

Used vs Refurbished vs Remanufactured

A lot of confusion in this space comes from sloppy terminology. Industrial Automation Company draws a useful line between “used” and “refurbished” components. Used parts are simply removed from service and sold as‑is, with no inspection, no testing, and usually no meaningful warranty. Refurbished parts, by contrast, are professionally cleaned, inspected, functionally tested, and typically carry a warranty, making them appropriate for critical equipment.

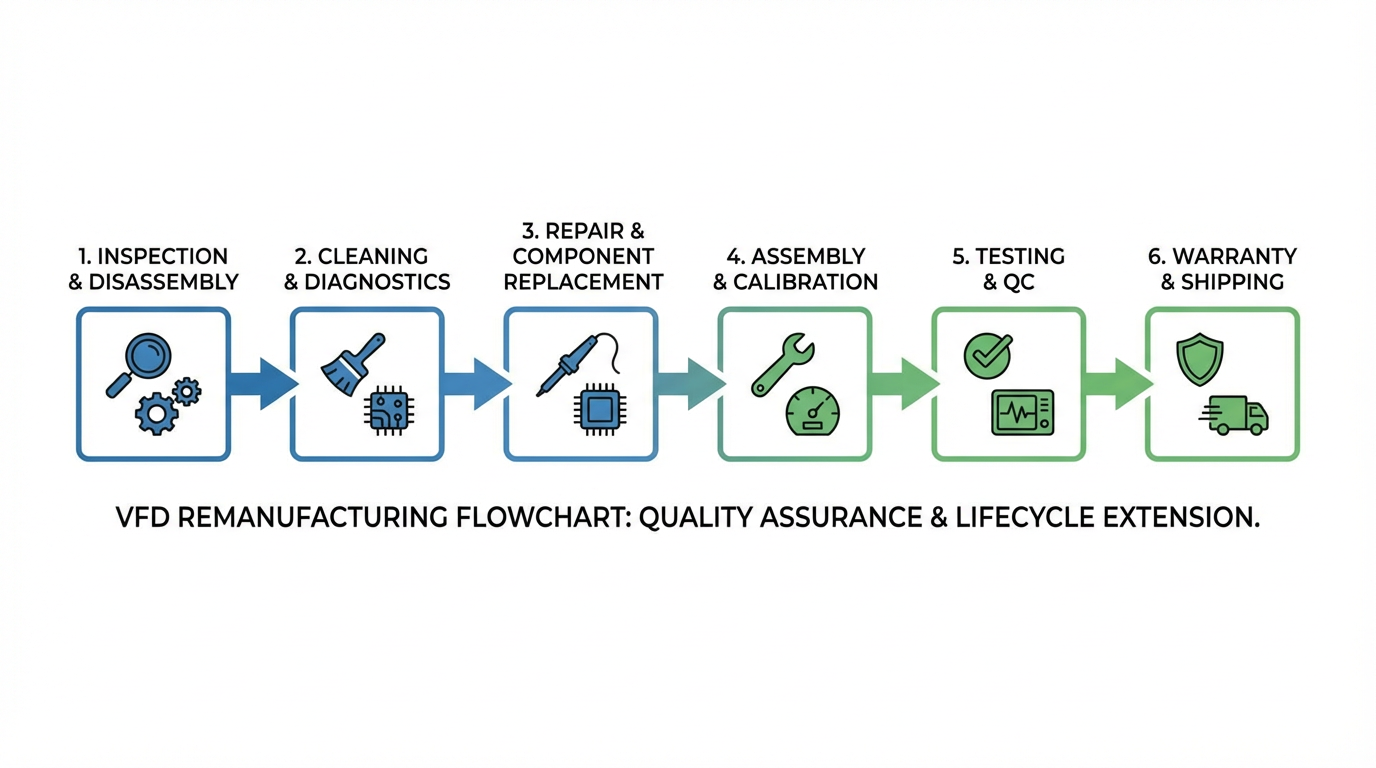

In day‑to‑day project work, most integrators treat a “remanufactured” VFD as a step beyond basic refurbishment. In practice, that usually means the drive has been fully disassembled, cleaned, inspected, and then rebuilt with replacement of known wear items such as cooling fans and DC bus capacitors, followed by full functional and load testing that mimics real‑world operating conditions. The intent is to bring the unit back to performance comparable to new equipment.

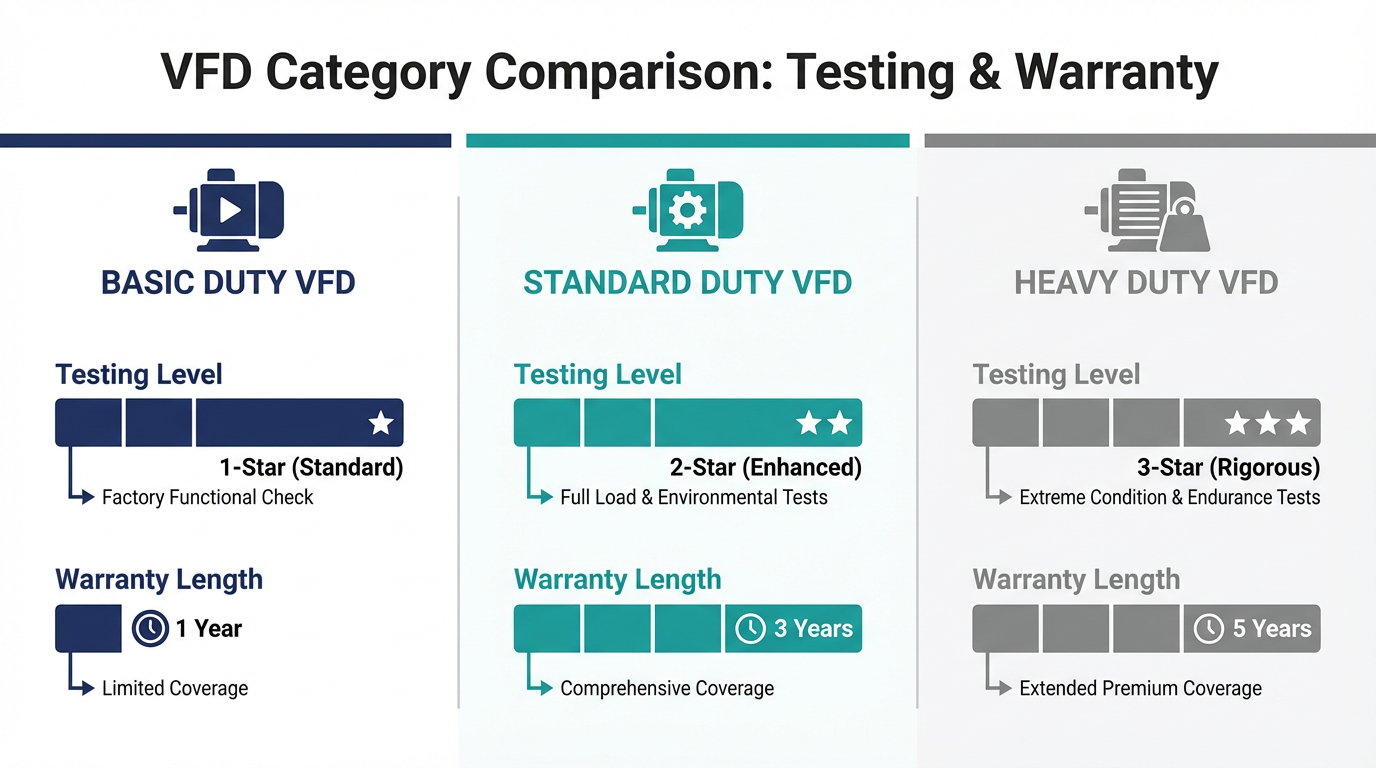

The distinction is not academic. When a drive fails on a critical pump and production is bleeding cost every hour, a cheap used VFD pulled from a warehouse shelf is a wild card. A properly remanufactured drive, by contrast, has documented testing, traceable repairs, and a warranty that reflects the supplier’s confidence in the result. Industrial Automation Company notes that a strong multi‑year warranty on refurbished components can be roughly double typical industry norms and serves as a practical proxy for underlying quality.

The table below summarizes how these categories are typically treated in serious industrial environments.

| Category | Typical condition and work performed | Testing level | Warranty expectation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Used | Pulled from service, little or no cleaning or repair | Minimal or none | Often “as‑is,” very limited or no warranty |

| Refurbished | Cleaned, visually inspected, basic repairs as needed | Functional tests, sometimes light load tests | Usually a limited warranty |

| Remanufactured | Disassembled, critical components renewed, rebuilt to original intent | Documented functional and load tests under duty | Strong multi‑year warranty is common |

Whatever labels vendors use, the quality standard should be based on the work actually done and the evidence they can show, not the marketing term stamped on the box.

What “Good as New” Really Means for a VFD

To set realistic standards for remanufactured drives, it helps to revisit what makes a VFD reliable in the first place.

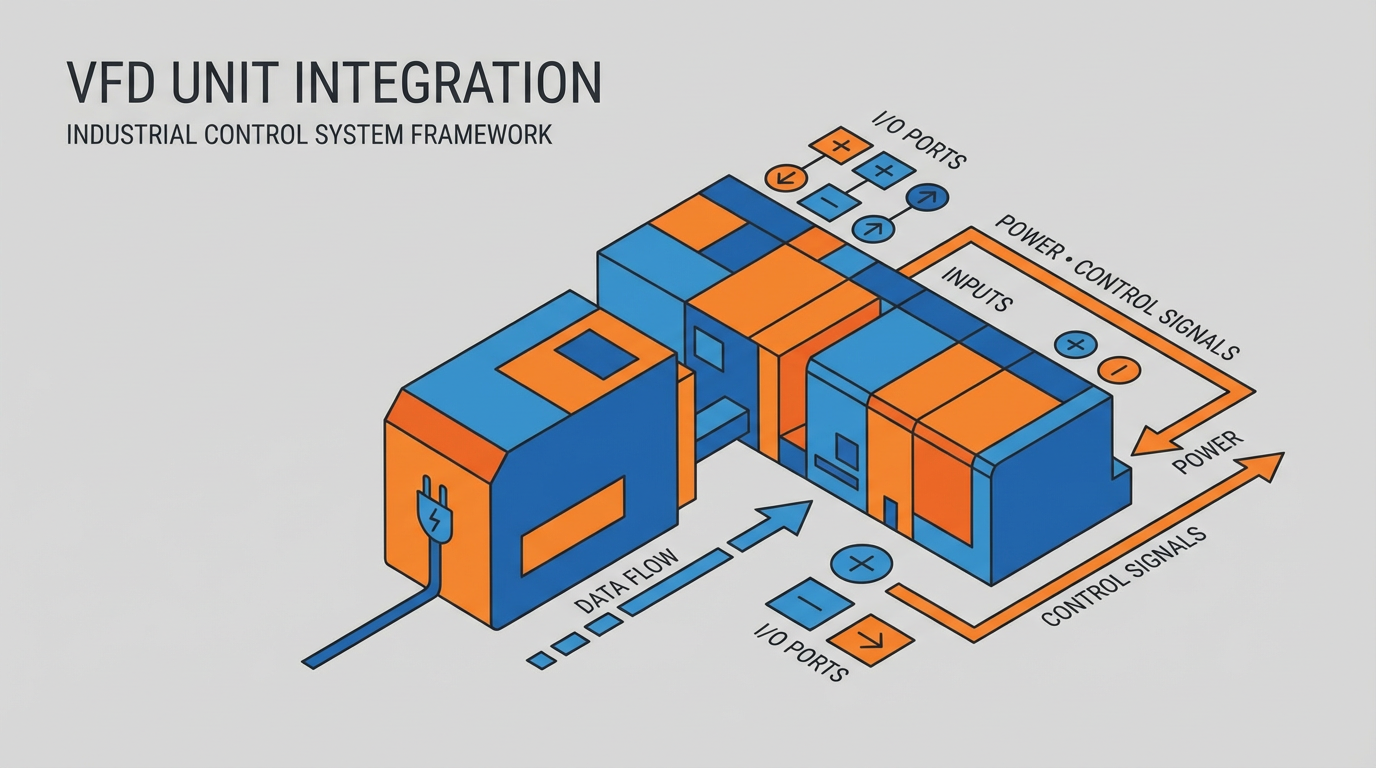

Plant Engineering describes the typical VFD architecture as an AC–DC converter feeding a DC link with capacitors, followed by a DC–AC inverter that uses insulated‑gate bipolar transistors to create a pulse‑width‑modulated output for the motor. Industrial Electrical Company and other service providers emphasize that reliability depends not only on the power section but also on the control electronics, cooling system, enclosure, and motor application.

Illinois Electric highlights how reliability is usually quantified and validated. Mean Time Between Failures, or MTBF, is one of the primary metrics, representing the average operating time between inherent failures based on field data and statistical analysis. Environmental testing subjects drives to temperature extremes, humidity, dust, and vibration to ensure that they withstand the realities of plant environments. Component‑level analysis drills into capacitors, semiconductors, and cooling hardware to identify weak links and determine when professional repair or replacement is appropriate.

Major manufacturers such as ABB use Reliability Demonstration Testing during development to prove that new drives can meet their target lifetimes under accelerated stress. Drives are run in controlled environments where temperature and thermal cycling exceed normal application levels. If a sample of units survives the test profile, the manufacturer gains statistical confidence that the design will last in the field. Additional Accelerated Life Testing runs drives to failure at multiple stress levels to refine life models and understand failure modes.

A remanufactured VFD will not get the same multi‑year development test program, but the quality standard has to respect the same principles. You are betting your uptime on the assumption that the remanufactured unit still behaves like the design that passed MTBF and reliability testing. That means the reman process must address the same components and stress factors that drive failure in the field.

Non‑Negotiable Quality Standards for Remanufactured VFDs

Documented Functional and Load Testing

For PLCs, HMIs, and VFDs, Industrial Automation Company stresses the importance of documented functional and load testing that mimics real operating conditions. For drives, this should include powering the unit with appropriate input voltage, running a motor or test load through the expected speed range, and exercising both constant‑torque and variable‑torque profiles where relevant.

From a drive engineering standpoint, that test should verify not only that the motor spins but that the VFD’s current draw and output behavior match what you would expect for a healthy system. Verivolt notes that monitoring both input and output currents is key to validating load performance and detecting problems such as belt loss or stalled loads. They also emphasize watching the high‑frequency pulse‑width‑modulated voltage for overshoots and dropouts, and checking voltage and current balance across phases to avoid overheating and uneven torque.

In my own shop, I look for three things in a test report before I trust a remanufactured drive. First, basic configuration tests that show the drive accepts parameters, communicates over its intended fieldbus, and responds correctly to start, stop, and speed reference commands. Second, load tests that run the drive through its operational speed range with current, voltage, and temperature recorded. Third, fault and protection checks that confirm overload protection, overvoltage and undervoltage trips, and safe response to common fault conditions.

If a supplier cannot produce that level of documentation, you are buying guesswork, not quality.

Component‑Level Repair and Inspection

A remanufactured VFD that has not addressed underlying component wear is just a cleaned‑up used drive. The maintenance guidance from OmniMech, Industrial Electrical Company, and Joliet Technologies makes it clear which components typically define drive life.

Power semiconductors such as IGBTs and MOSFETs need to be inspected for heat damage, cracking, and degraded thermal interfaces. DC bus capacitors naturally age; OmniMech recommends checking for bulging, leaks, corrosion, or rising equivalent series resistance and replacing them on a planned basis. Cooling systems, including fans, heat sinks, and air filters, must be cleaned or renewed. Dust clogged heat sinks and failed fans are a recurring root cause of overtemperature trips and premature failures, a pattern that shows up repeatedly in service case studies from Delta Automation and Global Electronic Services.

Control boards should be inspected for corrosion, burned components, and cracked solder joints, then cleaned carefully to remove conductive dust. Industrial Electrical Company notes that NEMA 1 vented enclosures admit more debris and therefore require more frequent cleaning and inspection than more tightly sealed NEMA 12 housings.

When a remanufacturer can show that they routinely replace high‑wear components, not just those that have already failed, and that they perform board‑level inspection and cleaning, you are much closer to a truly renewed drive.

Standards Compliance and Safety

Clemson University’s VFD specification for campus projects is a good example of institutional expectations. It requires drives to comply with applicable UL, NEMA, and IEEE standards; to provide motor overload protection, fault diagnostics, and protective functions including overcurrent, overvoltage, undervoltage, and overtemperature; and to limit harmonics and electrical noise so that the broader power system remains stable.

These requirements do not disappear when a drive is remanufactured. You still expect the unit to trip safely on faults, to protect the motor from overload, and to behave predictably on the power system. Control Engineering’s guidance on preventing VFD faults underscores how critical correct overload settings, proper wiring and grounding, and surge protection are to avoiding damage from voltage spikes, harmonics, and unbalanced voltage.

From a project standpoint, I expect a remanufacturer to confirm that the unit’s protection functions have been verified, that any firmware updates applied are compatible with the installed base, and that the drive still fits within the original application’s standards envelope. That does not mean they must re‑certify the drive like a new design, but they should not return a unit whose behavior no longer matches the tested configuration the plant originally approved.

Power Quality, Thermal Performance, and Cooling

Heat and power quality are the two most common silent killers of drives in the field. Global Electronic Services emphasizes that many VFD failures are gradual, driven by chronic overheating and unstable power rather than dramatic catastrophic events.

Plant Engineering highlights that VFDs should be mounted in environments and enclosures appropriate to their ratings, and that heat load must be managed carefully. Many drives are designed for ambient conditions around 115°F; pushing them above that without adequate cooling quickly erodes margin. Industrial Electrical Company warns that vented enclosures accumulate dust and debris that block airflow and cause heat buildup, which in turn accelerates capacitor and semiconductor aging.

Control Engineering recommends maintaining input voltage within typical limits of about plus ten percent and minus fifteen percent of nominal, and keeping phase imbalance low to avoid excessive DC bus ripple and capacitor stress. Line reactors, surge arrestors, proper grounding, and, in tougher environments, isolation transformers are cited as effective tools to tame spikes and harmonics.

When I evaluate remanufactured VFDs, I expect the supplier’s test procedure to include elevated temperature operation consistent with the drive’s ratings, verification that fans start and run correctly, and checks that thermal sensors and overtemperature alarms still operate as intended. Simply powering up a drive on the bench for a few minutes in a cool shop is not enough to call the unit field‑ready.

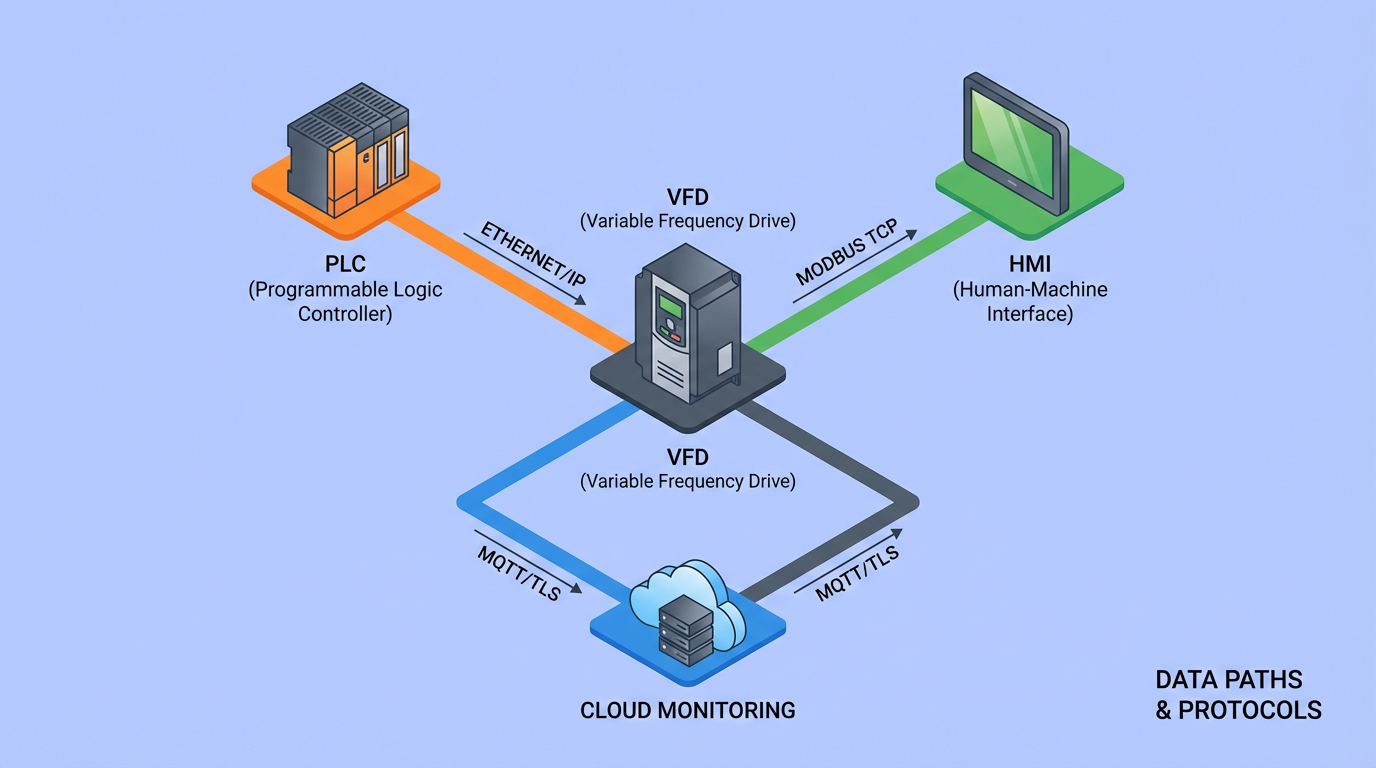

Controls and Network Integration

Modern VFDs are not just power electronics; they are networked smart devices. Clemson’s specification calls for drives to support remote start and stop, speed reference, feedback, alarms, and status over analog and digital I/O as well as open protocols such as BACnet or Modbus so they integrate cleanly with building automation systems. Precision‑oriented guidance on VFDs highlights additional protocols such as Ethernet‑based fieldbuses in industrial settings.

For remanufactured drives, that means quality standards must include verification of all intended control paths. Digital inputs and outputs, analog references and feedback, relay outputs, and serial or Ethernet ports should all be exercised. Parameter maps must match the expectations of the PLC or building automation system. Firmware versions should be compatible with existing engineering tools and any higher‑level diagnostics you rely on.

Plants increasingly use drive diagnostics and networked monitoring as part of condition‑based maintenance programs, as described by Plant Engineering and ReLiAmag. If a remanufactured drive returns with disabled or incompatible communications, it undermines those reliability programs. A good remanufacturer understands that and includes integration checks in their quality standard.

Warranty, Documentation, and Traceability

Industrial Automation Company points out that warranty length and coverage are strong signals of reliability. They cite an example of a two‑year warranty on refurbished components, roughly double what many in the market offer. A remanufacturer willing to stand behind their work for that long is demonstrating both confidence and a commitment to support you when failures occur.

Beyond warranty length, documentation matters. Clemson’s specification and other institutional standards call for clear submittals: wiring diagrams, performance data, software and firmware information, spare parts lists, and operation and maintenance manuals. For remanufactured drives, add to that a test report, a list of replaced components, and clear markings for firmware and hardware revisions.

Industrial Automation Company also emphasizes transparent sourcing and a straightforward return policy. You want to know that parts have traceable origins rather than coming from unvetted secondary markets, and you want confidence that if a remanufactured drive exhibits early‑life problems, it will be repaired or replaced quickly.

In my experience, suppliers who invest in thorough documentation and traceability also tend to invest in rigorous internal processes.

Those who treat remanufacture as simple board swapping and basic cleaning usually struggle to provide detailed paperwork, and that is a red flag.

Maintenance Expectations After Remanufacture

A remanufactured VFD is not a maintenance‑free device. In fact, the business case for remanufacture is strongest when you pair it with disciplined preventive care.

Delta Automation, a service provider with more than twenty‑five years in industrial electronics, reports that service data from over one thousand VFD repairs show roughly sixty percent of failures could have been prevented with routine preventive maintenance. Their experience across multiple brands lines up with what Plant Engineering, Control Engineering, Industrial Electrical Company, and Joliet Technologies all highlight: heat, contamination, loose connections, and neglected firmware are behind a large fraction of drive problems.

OmniMech’s comprehensive VFD maintenance guide estimates that proactive maintenance can extend VFD lifespan by about thirty to fifty percent while costing only around fifteen to twenty percent of full replacement. That economics is even more compelling for remanufactured units, where each additional year of reliable service improves the overall return on the original and remanufacture investments.

For a plant standard, I recommend formalizing a schedule similar to what OmniMech describes. Daily checks focus on visual condition and temperature, listening for unusual noises, and watching for new alarms. Weekly tasks cover cleaning filters, checking for vibration and cable strain, and reviewing logs. Monthly and quarterly windows are used for deeper tests such as thermal imaging, voltage and current balance measurements, emergency stop and interlock tests, and internal cleaning and tightening. Annual work often includes parameter backup, replacement of fans as needed, detailed board inspection, and, for critical systems, support from specialized service providers.

The key message is simple: a remanufactured drive that is not maintained will fail almost as surely as a new drive that is neglected. Quality standards should therefore include not only what happens in the remanufacturing shop but also the maintenance practices expected in the field.

Environment, Installation, and Monitoring

Even the best remanufactured VFD will not stay healthy if it is installed in a poor environment or monitored blindly.

Industrial Electrical Company explains how NEMA enclosure ratings influence maintenance needs. Vented NEMA 1 drives in dusty indoor spaces demand more frequent cleaning than sealed NEMA 12 units. Plant Engineering notes that in harsh or wet areas, stainless steel NEMA 4X enclosures or properly rated motor‑mounted inverters may be required, though they introduce cooling challenges. Plant Engineering’s review of VFD safety and maintenance gives examples of drives intended to operate in ambients up to roughly 115°F, with elevated heat and direct sunlight causing derating and overtemperature trips if not managed.

Environmental control is not just about temperature. Joliet Technologies and Control Engineering highlight the role of dust, moisture, and corrosive contaminants in driving corrosion and tracking on circuit boards. Properly sealed enclosures, clean filters, and dry, climate‑controlled equipment rooms dramatically improve VFD life expectancy.

Monitoring and diagnostics close the loop. ReLiAmag describes how condition‑based maintenance uses tools such as thermal imaging, vibration analysis, and electrical signature analysis to detect emerging problems. Verivolt underscores the value of tracking voltage and current balance on VFD inputs and outputs to catch issues before they become failures. Plant Engineering describes modern platforms that treat the drive itself as a sensor, reporting temperatures of critical components, fan runtime, and detailed fault histories.

For remanufactured VFDs, that means your quality standard should include provisions for instrumenting and trending their behavior just as you would for new drives.

It also means working with remanufacturers who understand and support condition‑based maintenance, rather than treating drives as black boxes that are “good until they fail.”

Pros and Cons of Remanufactured VFDs Versus New

From a systems integrator’s standpoint, remanufactured drives are neither magic nor second‑class by definition. They are tools with strengths and limitations.

On the plus side, remanufactured VFDs offer substantial cost savings. Industrial Automation Company notes that refurbished automation parts often deliver savings in the range of thirty to seventy percent compared with new units. The LinkedIn discussion on refurbishing drives points out that lead times for new drives can delay critical operations, whereas refurbishing often restores service faster. Keeping the same model in service also avoids the engineering time required to adjust wiring, control logic, and operator training when new drive families are introduced.

Sustainability is another real benefit. The University of Manchester research cited on refurbishing VFDs suggests that refurbish‑over‑replace can be up to ninety‑one percent more sustainable, because it extends product life and reduces electronic waste and raw material demand. That aligns with broader corporate sustainability goals in many plants.

The potential downsides are mostly about variability and support. Industrial Automation Company addresses myths that refurbished parts are inherently unreliable or that their quality cannot be verified; in practice, properly tested refurbished components can perform much like new equipment. However, quality is not uniform across the market. Some suppliers perform only superficial cleaning and basic power‑up tests, leaving deeper issues unaddressed. Others cannot provide clear documentation, traceability, or robust warranty support.

Another concern is OEM service coverage. Refurbished or remanufactured drives typically sit outside OEM service agreements, even if they perform well. That is usually acceptable if your internal maintenance capability and your remanufacturing partner are strong, but it should be recognized explicitly in your risk assessment.

The right way to navigate these tradeoffs is simple. For high‑criticality applications with extreme safety or uptime consequences, you may choose new drives or remanufactured units only from suppliers whose processes rival those of the OEM. For legacy or lower‑criticality assets, remanufactured drives from reputable suppliers often deliver the best balance of cost, lead time, and reliability.

How to Qualify a Remanufactured VFD Partner

When I am asked to sign off on a remanufactured drive for a critical project, I look less at the catalog and more at the process behind it. The following dimensions, grounded in the sources discussed above, form a practical checklist.

First, testing and certification. The supplier should be able to explain their functional and load testing regime, show sample test reports, and demonstrate that they exercise communications, protection functions, and realistic duty cycles. Their approach should echo the emphasis on functional and load testing called out by Industrial Automation Company and the measurement practices described by Verivolt.

Second, component policy. A quality‑focused remanufacturer can clearly state which components they routinely replace by policy, such as cooling fans and DC bus capacitors, versus those they replace only on failure. Their practices should mirror the preventive recommendations from OmniMech, Delta Automation, and others, not fight against them.

Third, documentation, warranty, and returns. Look for wiring and configuration documentation, a detailed report of work performed and components replaced, clear firmware version records, and an operation and maintenance guide. Warranty duration and responsiveness should align with examples like the two‑year coverage mentioned by Industrial Automation Company, and the return policy should be straightforward enough that your planners can treat reman units as reliable assets, not one‑off experiments.

Fourth, sourcing and traceability. You should know where cores come from and what screening they undergo. Transparent sourcing, as emphasized by Industrial Automation Company, helps avoid surprises from counterfeit parts or heavily abused units entering your critical spares inventory.

Fifth, support culture. The best remanufacturers think like partners. They advise on preventive maintenance intervals, voltage and harmonic issues, environmental conditions, and integration pitfalls, drawing on the same body of best practices referenced by Plant Engineering, Control Engineering, and the various maintenance‑focused providers. When a supplier can talk fluently about MTBF, environmental testing, and field data, as described by Illinois Electric, you are dealing with an organization that appreciates reliability, not just repair.

A concise way to summarize these expectations is to treat remanufactured drives as engineered products, not commodities. If you would not accept a new drive without evidence that it meets your technical and reliability standards, you should hold remanufactured units to the same bar.

Short FAQ on Remanufactured VFD Quality

Are remanufactured VFDs as reliable as new units?

They can be, when the remanufacturer follows disciplined processes. The evidence from companies like Industrial Automation Company is that properly tested refurbished components can perform like new hardware. Field experience, along with reliability concepts such as MTBF and environmental testing described by Illinois Electric, shows that the dominant factors in VFD reliability are design quality, component health, installation, and maintenance. A remanufactured drive that has had critical components renewed, has passed documented load testing, and is installed and maintained according to best practices can deliver reliability very close to a new drive.

How long will a remanufactured VFD last?

There is no single number because life depends heavily on environment, loading, and maintenance. What we do know, from maintenance guidance and case data cited by Delta Automation and OmniMech, is that proactive preventive maintenance can extend VFD lifespans by roughly thirty to fifty percent, and that a large share of failures are preventable with routine inspection, cleaning, and connection tightening. A remanufactured drive that starts with renewed components and then receives disciplined preventive care can deliver many additional years of service, often long enough to justify the investment multiple times over.

When should I choose remanufacture instead of buying new?

Remanufacture makes the most sense when the existing drive model integrates cleanly with your controls, the surrounding equipment has plenty of life left, downtime costs are high, and new drives carry long lead times or would force redesign of panels and software. Industrial Automation Company and the LinkedIn discussion on refurbishing drives highlight additional advantages for legacy systems and sustainability goals. When a drive is fundamentally mismatched to the application, is repeatedly failing despite proper maintenance, or lacks modern safety or communication features that you genuinely need, then a new drive or a modernized design may be the better move.

Closing

In every plant where I have been trusted as a systems integrator and project partner, the decisions that stick are the ones grounded in clear standards, not guesswork. Remanufactured VFDs are no exception. When you insist on documented testing, thoughtful component renewal, robust warranties, and disciplined maintenance, a remanufactured drive stops being a compromise and becomes a strategic asset. Set the bar high, choose partners who live by it, and your drives—new and remanufactured alike—will quietly do their job while your operations team focuses on what really matters: running the plant.

References

- https://oasis.library.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2750&context=rtds

- https://cufacilities.sites.clemson.edu/documents/capital/Variable%20Frequency%20Drive%20Specifications.pdf

- https://www.womentech.net/how-to/automated-remediation-and-self-healing-systems

- https://www.automation.com/article/what-best-vfd-design-installation-plan

- https://www.controleng.com/10-essential-maintenance-and-troubleshooting-tips-for-vfds/

- https://devops.com/using-generative-ai-for-issue-remediation-and-software-reliability/

- https://gesrepair.com/why-your-industrial-vfds-are-failing-and-how-to-prevent-it/

- https://www.illinoiselectric.com/single-post/how-is-variable-frequency-drive-reliability-measured

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/benefits-refurbishing-variable-frequency-drives-david-griffin

- https://www.plantengineering.com/how-to-ensure-reliable-motor-operation-with-variable-frequency-drives/

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment