-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Critical Spares Management Services for Industrial Operations

When One Missing Part Stops the Whole Plant

After decades integrating control systems and supporting plants through midnight breakdowns, I can tell you that critical spare parts are often the difference between a short pause and a full-blown production crisis. The pattern is familiar: a drive module, PLC I/O card, or motor starter fails, everyone assumes the storeroom has it, and then the technician opens an empty bin. What follows is cannibalizing another line, paying for rush shipping, and explaining to customers why orders are late.

Research backs up what maintenance teams feel every day. SDI has reported that more than three-quarters of manufacturers have experienced shutdowns because the right spare was not available. At the same time, many sites have millions of dollars of parts aging on shelves. Critical spares management is about resolving that contradiction: keeping your most important equipment covered, while not turning the storeroom into an uncontrolled bank vault for inventory.

A critical spares management service takes what is often an informal, spreadsheet-driven activity and turns it into a structured, data-backed discipline. For industrial automation and control hardware, where lead times, product lifecycles, and obsolescence are unforgiving, that service can be the most cost-effective reliability investment you make.

What Counts as a “Critical” Spare?

Different organizations use slightly different labels, but the underlying logic is consistent across reputable sources such as eMaint, Verusen, and SDI. Critical spare parts are those whose absence brings serious consequences: immediate downtime, safety or environmental risk, or breach of tight customer or regulatory commitments. They are often expensive and slow-moving. You might not touch them for years, but when you need them you need them now.

Practitioners also distinguish several related categories. Strategic spares are parts you hold because of long lead times, obsolescence risk, or availability concerns over the life of the asset. Insurance spares are the rare, high-cost subset of strategic spares that protect you against catastrophic failures with very long repair or replacement times. By contrast, non-critical or low-risk parts are items you can source quickly from reliable suppliers without risking major business impact.

A clear taxonomy is essential because it drives stocking policy, ownership, and placement. The goal is not to hoard everything on-site, but to match stocking decisions to the risk profile of each part and the realities of your supply chain.

A simple way to visualize the differences is shown below.

| Spare type | Description | Typical use case | Main trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Part whose absence causes immediate downtime or safety/environmental risk | PLC CPU, safety relay, key drive or motor on bottleneck asset | Higher on-hand stock, strict controls, intensive preservation |

| Strategic | Part held to cover long lead times or obsolescence risk | Legacy HMI panel, specialty gearbox | Moderate stock, periodic review as technology and demand change |

| Insurance | Rare-use, very high-cost spare kept for catastrophic failures | Large transformer, major turbine component | Significant tied-up capital versus avoiding extreme downtime |

| Non-critical | Low-impact, easily sourced components | General hardware, common sensors | Lean stocking, rely on supplier responsiveness |

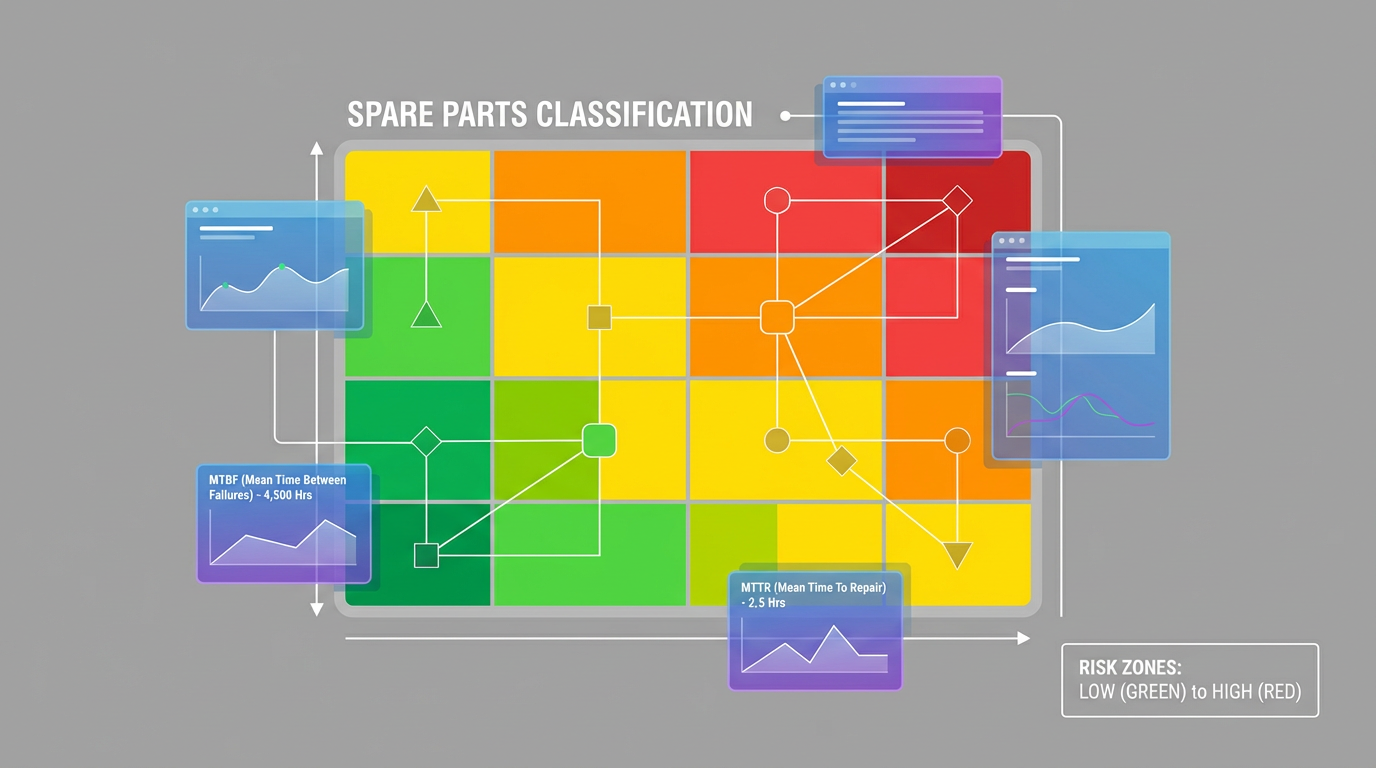

In practice, we classify spares using equipment criticality, failure history, mean time between failures (MTBF), mean time to repair (MTTR), lead-time data, and the availability of substitutes.

Verusen and others recommend treating this as an explicit, risk-based exercise rather than relying solely on tribal knowledge, because static, undocumented assumptions are a major cause of excess inventory and surprise stockouts.

Why Spare Parts Inventory Is Harder Than Regular Inventory

Traditional inventory planning was built for items that move steadily: finished goods, consumables, or direct materials. Critical spares behave differently. Demand is intermittent and often lumpy. You can go months without touching a PLC output card and then suddenly need three in a week because of a common failure mode. SmartCorp and others have shown that trend-based forecasting applied to this kind of pattern tends to either understate the risk of a cluster of failures or massively overshoot and inflate stock.

At the same time, holding costs for spares are high. Capital is tied up, storage and environmental controls must be maintained, and certain items degrade over time. Prometheus Group highlights that many bearings, belts, and rubber components have practical shelf lives; if you do not preserve and rotate them, you can install failures straight from the storeroom. That turns your insurance spares into hidden liabilities.

Supply chains for industrial parts are also more fragile than they may look. Research on maritime operations in peer-reviewed journals has described how engine spare lead times and port constraints can force costly schedule deviations. Studies cited by Our World in Data and others have chronicled how global shocks and component shortages ripple through supply networks. The Tennessee Valley Authority’s own oversight attempts to evaluate critical spare programs underscore that this is not just a private-sector concern.

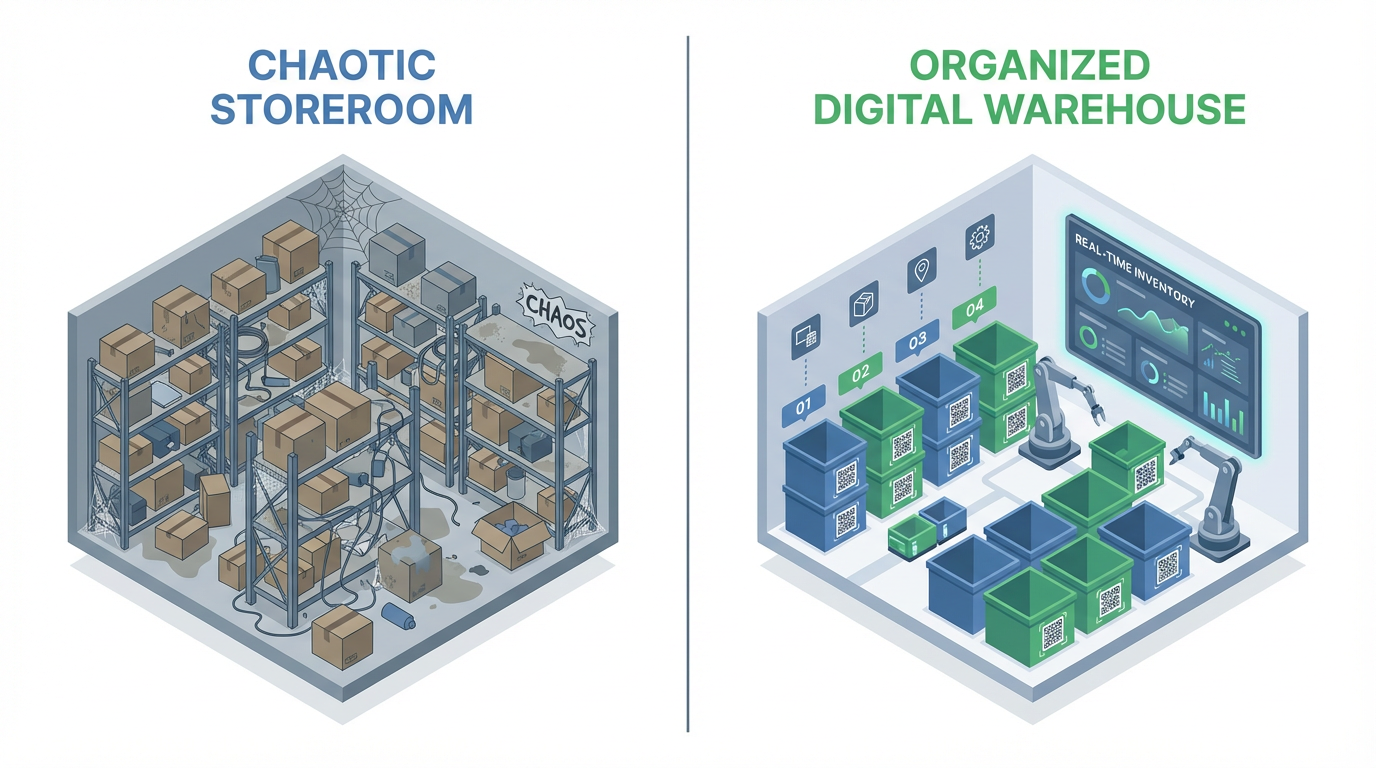

The net effect in many plants is awkward: shelves full of obsolete or duplicated stock, yet recurring expedites for truly critical items. An effective critical spares management service attacks both sides of this problem with data, discipline, and design.

The Foundation: Criticality Analysis and a Clean Asset Model

Every reliable critical spares program starts with a solid understanding of the assets you are protecting. In my experience, the most successful initiatives follow a sequence that aligns closely with guidance from eMaint, SDI, and Agilix.

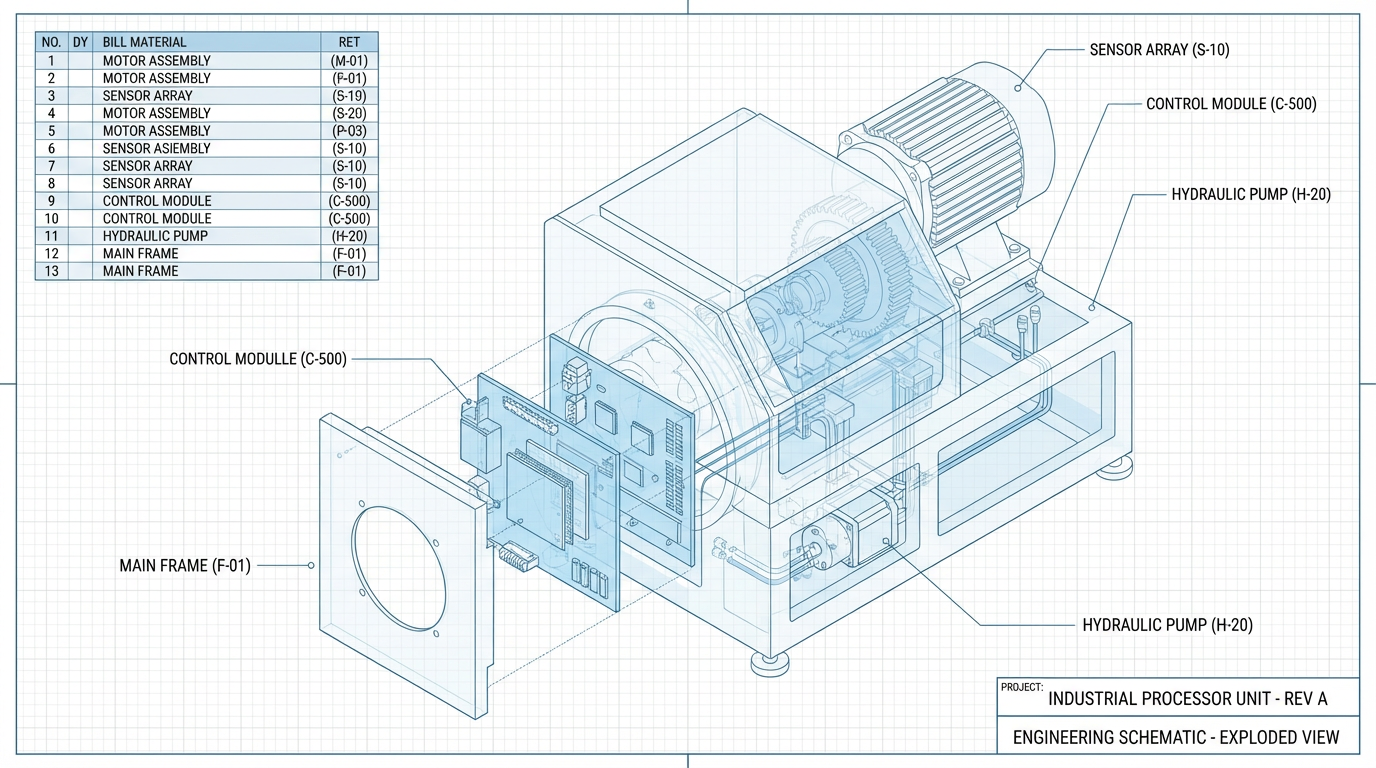

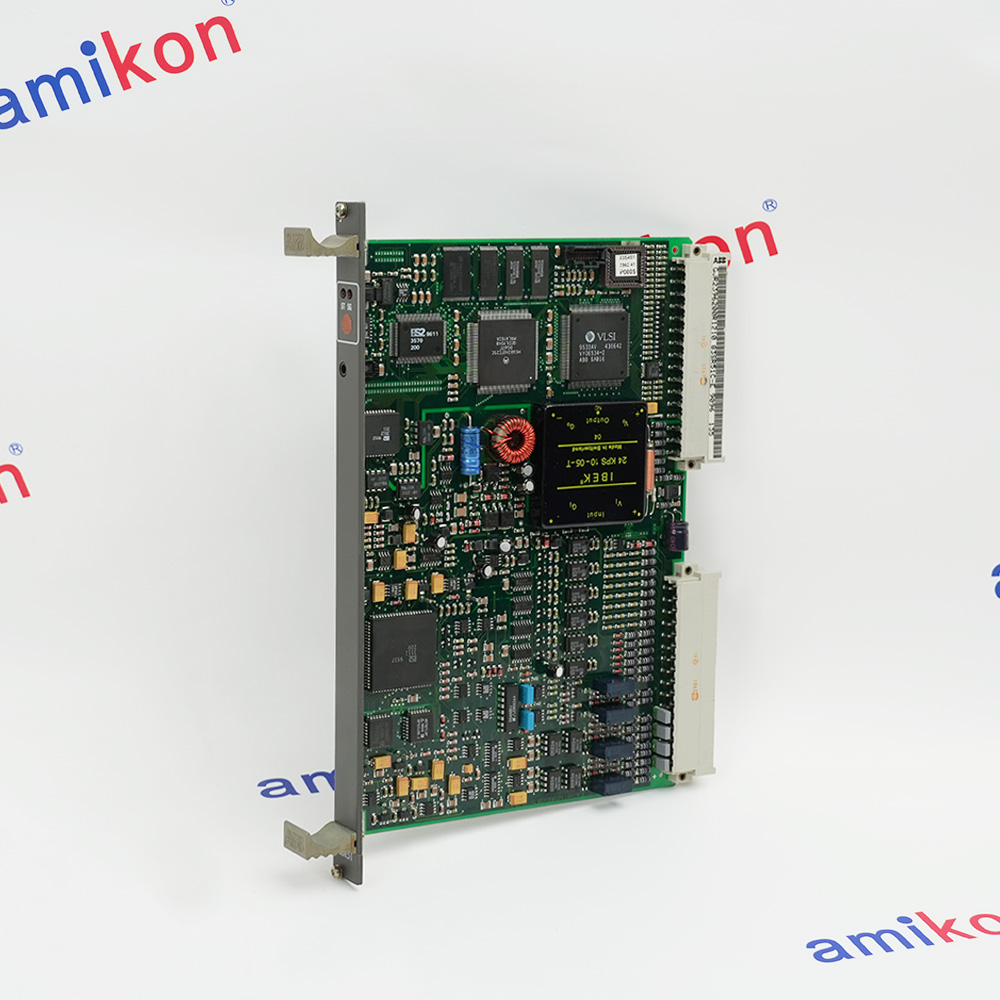

The first step is to build or validate a complete asset register and plant model. That includes every production-critical asset, its operating context, functional criticality, and current condition. Agilix and Rockwell Automation have popularized the term Installed Base Evaluation for this kind of structured review. The goal is to surface what equipment you really have, where it is in its lifecycle, which parts are still supported, and which are discontinued or pending obsolescence.

The second step is to connect each critical asset with an accurate bill of materials (BOM). Articles from Prometheus Group and Sortly emphasize that without a BOM that actually matches what is installed, spare parts planning is little more than guesswork. A good BOM is not just a list of part numbers; it includes quantities, alternates, and the relationships between assemblies, subassemblies, and field-replaceable units.

Once assets and BOMs are in order, you can run a structured criticality analysis. Verusen and other practitioners recommend defining criticality using explicit criteria such as downtime impact, safety and environmental consequences, lead time, and substitution options. Prometheus suggests using a risk matrix to map those factors to stocking decisions: do not stock, standard stock, or critical stock. Research from Standards Australia (AS/NZS/IEC 62550) takes a similar approach, treating criticality as a blend of failure likelihood and consequence.

This is where a critical spares management service earns its keep.

An experienced integrator will not just run a generic scoring model; they will calibrate criticality with your operations, your failure history, and your appetite for risk, then document the rationale so decisions stand up to audits and leadership scrutiny.

Data, CMMS, and QR Codes: The Digital Backbone

Once you know what matters, you have to keep track of it. Multiple sources, including SafetyCulture, Tractian, Partium, Prometheus Group, and Maintainly, converge on the same lesson: bad data and manual tracking are the root cause of many spare parts failures.

Effective services organize spare parts data into three governed layers, as recommended by Prometheus. Master data holds the standard description, manufacturer, part number, class, and attributes. Procurement data holds pricing, lead times, and vendor details. Usage data captures historical consumption, work-order associations, and which equipment consumed which part. If you skip this structure, you end up with duplicates, wrong lead times, and unreliable reports.

On top of this structured data, a modern CMMS or enterprise asset management system provides the transactional engine. SafetyCulture and eMaint highlight several key capabilities: linking parts to work orders so every consumption event updates stock; using barcodes or QR codes to identify items; enforcing permissions and audit trails; and triggering reorder suggestions based on minimum and maximum levels, safety stock, and supplier lead time. Maintainly goes further by promoting random location coding and QR labels on bins, which increases storage flexibility and density when managed in software.

Mobile access has become non-negotiable. Technicians should be able to walk into the storeroom, scan a QR label on a bin or motor, see the full history and remaining stock, and issue parts directly against a work order. Partium and similar platforms use visual search and AI-assisted data cleansing to identify parts from photos or incomplete descriptions and to normalize messy records. That reduces the time technicians spend searching and the risk of picking the wrong item, which is especially important in control panels where similar modules can have subtle and critical differences.

The benefit of this digital backbone is visibility.

Managers see current stock levels across sites, slow movers and obsolete items, true lead times, and consumption trends. Without that, any critical spares strategy is running in the dark.

Storeroom Design and Preservation: The Physical Side of the Service

The best data model is useless if the physical storeroom is chaotic. Maintainly, MDI, and practical guides from distributors all emphasize that layout and preservation are part of critical spares management, not an afterthought.

In well-run operations, heavy or bulky items such as motors and gearboxes live on lower, reinforced shelving, while small parts like fuses, terminals, and interlock switches are stored in labeled bins. Vertical shelving or mezzanine systems are reserved for lighter items where additional height is safe. Critical spares typically occupy a clearly defined zone with controlled access, often close to maintenance shops to minimize travel time during emergencies.

Workflow through the storeroom is just as important as layout. There should be a defined receiving area where new parts are inspected, labeled with barcodes or QR codes, and entered into the CMMS before they are shelved. Pick paths are organized so frequently used parts are easy to reach and seldom used items do not clutter front-line space. Sortly and others stress that every part must have a clear location and label; any item without both is effectively invisible under pressure.

Preservation routines are particularly vital for high-value spares. Prometheus Group recommends specific handling practices: keep rubber products out of direct sunlight, store belts flat rather than hanging, and periodically rotate large motor shafts to prevent bearing damage. Bearings themselves often have a practical shelf life measured in years, not decades, because lubricants degrade over time. A robust service includes defined care plans for spares, not just for operating equipment.

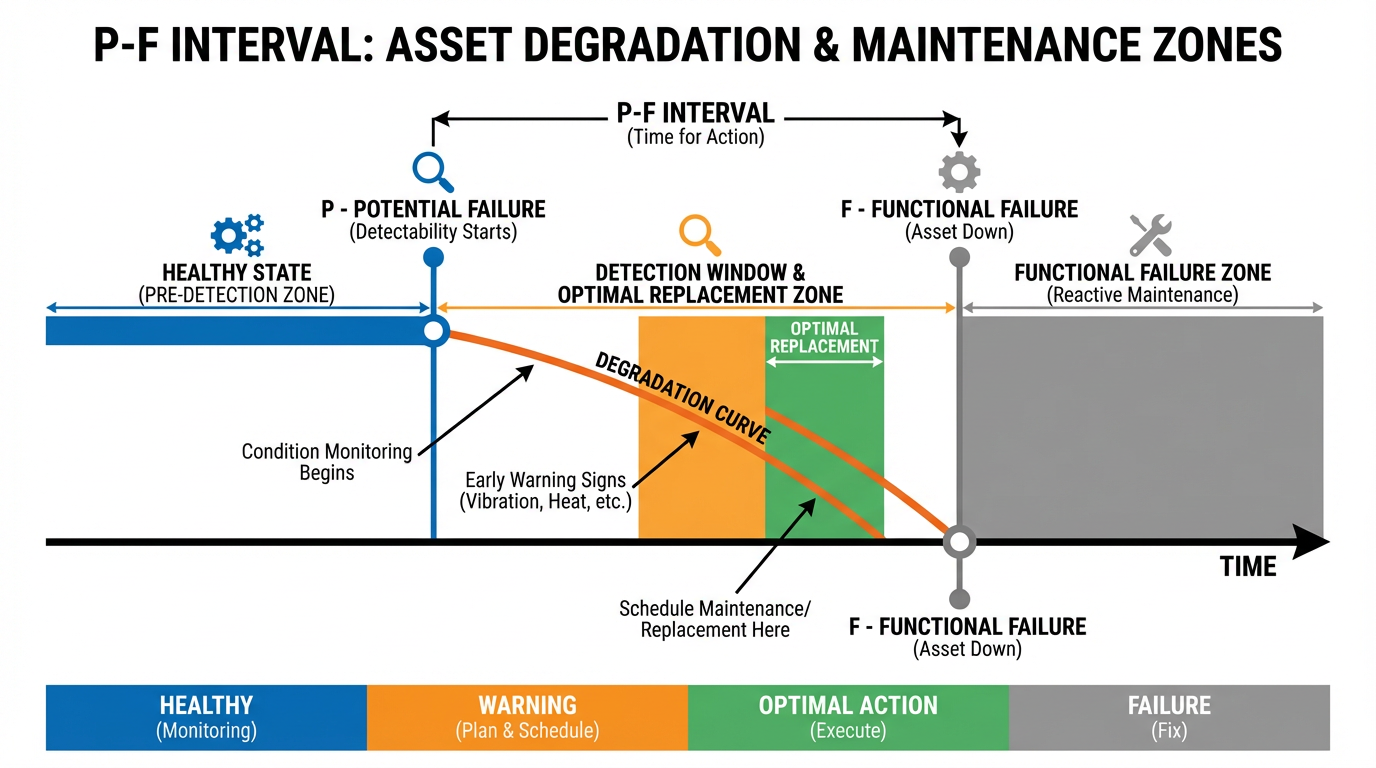

Maintenance Strategy and the P-F Interval: Linking Spares to Condition

Academic work on vessel engine maintenance and condition-based monitoring has clarified the link between maintenance strategy and spare parts policy. In that literature, maintenance approaches fall into three buckets: corrective (run to failure), preventive (time-based or calendar-based), and predictive or condition-based (using real-time monitoring and analytics to act when degradation is detected).

A key concept is the delay between when a defect becomes detectable and when functional failure occurs, often called the P-F interval. If the P-F interval is longer than your supplier lead time, you may not need to keep a physical spare on the shelf at all. You can rely on condition monitoring to trigger an order at the first sign of trouble, then schedule replacement during a convenient window before the failure occurs.

For example, vibration monitoring on a critical fan motor can give weeks of warning before a bearing failure. If your supplier can reliably deliver the bearing kit within a few days, a predictive maintenance program integrated with your CMMS can automatically raise a work order, reserve or order parts, and schedule the repair. Research in maritime applications has shown that integrating this kind of condition-based data with spare ordering decisions reduces both inventory levels and schedule disruptions.

In practice, a critical spares management service evaluates failure modes and P-F intervals for key assets and then categorizes spares accordingly.

For sudden, hard-to-detect failures or items with very long lead times, on-site inventory is essential. For gradual, well-monitored degradation with reliable suppliers, the service may recommend lower on-hand quantities and a tighter integration between condition monitoring and purchasing.

Who Owns the Spares, and Where Should They Sit?

Ownership and placement are often more contentious than technical questions. Research in the Journal of Business Logistics has examined how buyers choose between owning inventory themselves or using consignment and vendor-managed arrangements for critical spares. The findings are instructive: buyers tend to prefer consignment, where the supplier owns the stock but positions it at or near the plant, and they show a bias against speculative buying, especially when supply uncertainty is low.

Real-world programs echo these preferences. Rockwell Automation, for example, offers agreements where it owns critical automation spares held on the customer’s shelf, shares obsolescence risk, and provides warranties on tested remanufactured parts. Many OEMs and service providers offer vendor-managed inventory or parts replenishment bundles embedded in transport or maintenance contracts.

The core models can be summarized as follows.

| Model | Who owns inventory | Where it is stored | Strengths | Watch-outs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer-owned on-site | Plant | On-site storeroom or local warehouse | Maximum control and immediate access | High capital and carrying cost, obsolescence risk, demands strong internal processes |

| Consignment on-site | Supplier | On plant site but supplier-owned | High availability without tying up capital, shared obsolescence risk | Requires clear governance and reconciliation, may involve minimum terms or fees |

| Vendor-managed off-site | Supplier | Regional or central warehouse | Lower on-site footprint, professional inventory management | Longer response times unless backed by firm service levels and expedited delivery mechanisms |

| Hybrid or shared ownership | Shared or case-by-case | Combination of on-site and off-site | Flexibility to tailor arrangements to part criticality and business risk | More complex contracts and coordination, requires mature relationships and clear performance metrics |

A seasoned critical spares service helps you choose the right mix. For truly catastrophic, long-lead items, full on-site ownership may still be justified. For medium-critical parts with reliable suppliers, consignment or vendor-managed stock can reduce capital without increasing risk. The key is to align inventory placement with the criticality analysis, not convenience or historic habits.

Industry 4.0, AI, and Digital Spare Parts

Critical spares management is changing as fast as the assets themselves. Work on Industry 4.0 and digital asset management highlights how sensors, digital twins, and advanced analytics can transform spare parts strategies.

AI-driven platforms, such as those described by Verusen and Partium, use machine learning and large language models to cleanse and standardize parts data, detect duplicates, identify price differences across sites, and recommend optimal stocking levels. Instead of static ABC classifications and manual spreadsheets, services can now run continuous analyses that incorporate demand variability, lead-time performance, and business priorities. Verusen advocates an always-on criticality process that updates as conditions change, rather than once-a-year parameter reviews.

Another emerging theme is the idea of digital spare parts. Researchers such as Martin Boettcher and others have described how additive manufacturing and plasma metal deposition make it possible to hold certain spares as qualified digital designs instead of physical inventory. When needed, a metal component can be printed on demand, either in-house or via specialized partners, reducing storage and obsolescence risk. Work cited by Standards Australia and recent additive manufacturing literature suggests this is particularly promising for low-volume, high-value parts and older equipment where OEM support has faded.

Digital twins and advanced condition assessment further close the loop. When asset models, failure data, and spare-part options (stock, buy, or print) live in a unified digital asset management framework, you can make spares decisions as part of a broader reliability strategy, not in isolation. That kind of integration is no longer theoretical.

Parsable, for example, has reported productivity improvements of up to about 30 percent in organizations that adopt digital work instructions and real-time inventory tracking. Tractian has documented substantial maintenance cost reductions through predictive parts management. These results do not come from technology alone; they come from combining tools with disciplined processes, which is exactly what a mature critical spares service provides.

What a Critical Spares Management Service Should Deliver

From the viewpoint of a systems integrator who wants to be a long-term project partner rather than a one-time installer, a critical spares management service should be measured by outcomes, not just binders and dashboards. Those outcomes are well aligned with the benefits reported across sources such as eMaint, SDI, SmartCorp, and Partium.

First, the service should measurably reduce unplanned downtime attributed to missing or defective parts. That means fewer rush orders, fewer emergency visits to gray-market resellers, and fewer instances of cannibalizing parts from one machine to keep another limping along. It also means that the parts you do install from the shelf perform reliably, because preservation and rotation routines are in place.

Second, it should optimize inventory investment. The goal is not the lowest possible inventory value; it is the right inventory for your risk profile. Prometheus Group recommends tracking stock turns, stockouts, and the amount of inventory that has not moved for extended periods. A well-run service will help you retire truly obsolete stock, rationalize duplicates across sites, and negotiate better commercial terms with suppliers through improved visibility.

Third, it should embed spare parts into your maintenance and operations processes. Work orders drive consumption, preventive maintenance plans reserve required parts automatically, and condition monitoring alerts trigger parts reservations and orders in a consistent manner. In this model, the storeroom is not a separate world; it is a tightly integrated part of your reliability ecosystem.

Fourth, it should leave you with stronger governance and capability, not dependence. Verusen, Partium, and others stress the importance of training and knowledge retention. The best partners document data standards, help you standardize naming and classification, and train your people to use the systems, so that when staff change you do not lose control of the storeroom.

Pros and Cons of Outsourcing Critical Spares Management

The decision to outsource aspects of critical spares management to a specialist is not purely technical. Articles from Diversified Transportation Services, Agilix, and Rockwell Automation highlight both advantages and trade-offs.

On the positive side, specialized providers bring structured methodologies, dedicated tools, and access to broader market intelligence. They can perform thorough installed base evaluations, benchmark your inventory profile against similar operations, and manage vendor programs such as consignment and warranty-backed remanufacturing. Outsourcing can also shift some risk, especially for obsolescence and testing of electronics, and can remove carrying costs from your balance sheet when the supplier owns on-site inventory.

On the other hand, outsourcing introduces dependency risks and requires rigorous governance. You must define service levels for availability, response times, and quality. You also need clear rules for data ownership, integration with your CMMS or ERP, and decision rights over what is stocked where. Poorly structured arrangements can lead to misaligned incentives, where inventory is optimized for the provider’s economics rather than your uptime and risk profile.

A pragmatic approach is to treat critical spares management as a partnership. Retain ownership of strategy, criticality definitions, and performance oversight. Use external experts where they clearly add value, such as data cleansing, advanced analytics, or managing complex multi-site vendor programs. Above all, insist on transparency: the models, data, and assumptions driving stocking decisions should be visible and explainable to your team.

How to Get Started Without Boiling the Ocean

If your plant is typical, you already have a storeroom, a CMMS, and a long list of frustrations. The path forward does not have to be overwhelming, but it does have to be structured.

A sensible starting point is a focused criticality and inventory review around a limited scope: perhaps your top ten production-critical assets or a single process area. Build or validate the asset register and BOMs, run a structured criticality assessment using clear criteria, and compare the result to your current inventory. This often reveals obvious gaps, such as truly critical parts missing from stock, as well as surplus or obsolete items that can eventually be retired.

Next, stabilize your data and workflows. Clean up master data for the in-scope items, standardize descriptions and units, implement QR or barcode labeling, and ensure that every part movement in the scope flows through the CMMS. Several sources emphasize that even partial digitalization delivers benefits quickly; technicians spend less time searching, discrepancies are caught earlier, and reorder points can be tuned using real consumption data instead of estimates.

With that foundation, you can gradually expand the scope and consider more advanced measures, such as integrating condition monitoring alerts into spare parts planning, piloting vendor-managed inventory for specific classes of parts, or evaluating additive manufacturing options for a subset of low-volume, high-value components. At each step, measure results in terms of downtime, emergency orders, and inventory value.

FAQ

How do I know which parts should be treated as critical?

Begin with equipment criticality and failure history. Focus on parts whose failure would shut down high-value assets, create safety or environmental risk, or breach tough customer commitments. Use data such as MTBF, MTTR, and work-order history, combined with lead-time information and substitution options. Frameworks from eMaint, SDI, and Standards Australia suggest translating this information into clear risk scores and stocking rules, rather than relying solely on gut feel or OEM lists.

How many of each critical spare should I hold?

There is no single number that fits every situation. SmartCorp and Prometheus Group recommend treating stocking levels as an optimization problem that balances holding cost, stockout risk, and service-level targets. For long-lead or high-impact parts, practitioners often size safety stock to cover many months of expected demand, while for parts with short lead times and strong suppliers, one or two units may be enough. A critical spares service will use your consumption data, lead-time performance, and risk appetite to calculate sensible minimum and maximum levels for each part.

What if my storeroom is already full of obsolete or unknown parts?

That is more common than most managers admit. The first step is to stop the bleeding by enforcing standards on new parts: clean master data, proper labeling, and CMMS integration. In parallel, work through the existing stock systematically. Use installed base evaluations, OEM lifecycle status tools, and AI-assisted data cleansing to identify obsolete items, duplicates, and candidates for redistribution between sites. Several case studies referenced by Partium and Tractian have shown that organizations can reduce spare parts inventory by significant amounts while improving service levels, simply by removing noise and aligning stock with actual risk.

Closing Thoughts

Critical spares are not just boxes on shelves; they are risk mitigation instruments embedded in your production system. Treated casually, they drain capital and fail you when you need them most. Treated as a disciplined, data-driven service, they become a quiet but powerful enabler of uptime, safety, and customer trust. As a systems integrator, I see the best results where plants bring maintenance, operations, procurement, and trusted partners to the same table and make critical spares management a deliberate, ongoing practice rather than a one-time project.

References

- https://www.academia.edu/117569623/Rethinking_Critical_Spares_Management_in_the_Era_of_Industry_4_0

- https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstreams/7dbb87e1-3bab-4ff4-9123-6991ba6ac6d6/download

- https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/90788

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6394336/

- https://www.tvaoig.gov/reports/audit/review-npg-and-cgo-critical-spare-parts-programs

- https://repository.ceibs.edu/en/publications/managing-critical-spare-parts-within-a-buyer-supplier-dyad-buyer-/

- https://www.sc.edu/study/colleges_schools/engineering_and_computing/docs/research/predictive_maintenance_pdfs/20127partcriticality.pdf

- https://www.mdi.org/blog/post/spare-part-inventory-management-best-practices/

- https://www.bill.com/blog/parts-inventory-management

- https://www.dtsone.com/4-best-practices-for-spare-parts-management/

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment