-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Emergency Stock Programs for Critical Automation Components: A Veteran Integrator’s Guide

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

Why Emergency Stock Matters More Than Ever

Walk into almost any plant today and you will hear two conflicting messages. Finance wants lower inventory and better cash flow. Operations wants zero downtime and instant availability of every drive, PLC, and HMI in the building. If you have spent years integrating systems and supporting production the way I have, you know that living at either extreme is a recipe for trouble.

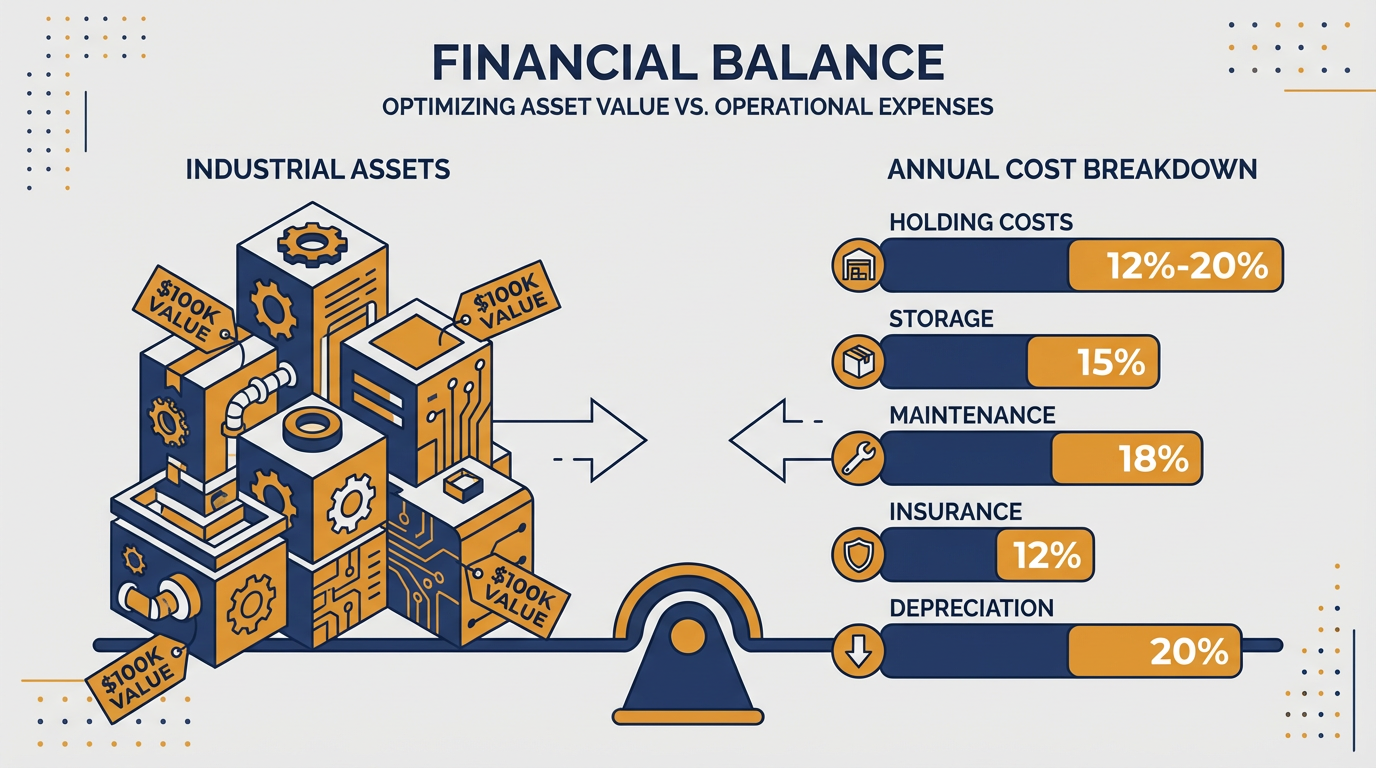

Modern automation is unforgiving. A failed PLC CPU, a dead HMI, or a smoked VFD can shut down a line that represents tens of thousands of dollars per hour in lost output. Fiix, a maintenance software provider, points out that understocking critical parts can easily stretch outages from hours into days or weeks, turning unplanned downtime into losses of thousands or even millions of dollars in lost production. At the same time, carrying excess inventory is not free. Fiix notes that typical storage and administration costs run around 12% to 20% of parts value per year. Put another way, $100,000.00 of stock on the shelf can quietly cost you another $12,000.00 to $20,000.00 every year before a single part is used.

Emergency stock programs for critical automation components are how mature plants resolve this tension. When they are designed well, these programs keep the handful of truly line‑stopping items available on demand while using proven inventory optimization techniques to avoid turning your storeroom into an expensive museum of obsolete parts.

This article lays out how to build that kind of program, based on what leading sources in inventory management, maintenance, and industrial safety have documented, and on what actually works on the plant floor.

What an Emergency Stock Program Really Is

An emergency stock program is not just “having a lot of spares.” Industrial Automation Co. describes an emergency parts list as a targeted inventory of high‑failure, long‑lead, and mission‑critical components kept on hand so plants can maintain uptime instead of waiting days or weeks for replacements. In practical automation terms, that means having the right PLC CPUs and modules, VFDs and servo drives, HMIs, industrial power supplies, safety devices, communication adapters, and essential wiring components ready to go when something fails.

The emphasis is on “targeted.” According to inventory optimization guidance from ABC Supply Chain and Amazon Business, effective programs segment inventory and set differentiated service levels. You do not try to achieve 100% availability on every sensor cable in the plant, because that is financially harmful and unnecessary. You do aim for extremely high availability on a narrow set of Tier 1 components whose failure stops production and where lead times are long or alternatives are risky.

In other words, an emergency stock program is a disciplined subset of your broader spare parts strategy, designed to protect production and safety where it matters most, while still respecting working‑capital constraints.

The Business and Safety Case for Emergency Stock

The direct cost of a failed drive or PLC is often obvious: the line stops, orders slip, overtime goes up, and management starts asking questions. What is less visible is the compound effect of weak parts management.

Fiix reports that in many operations, 10% to 25% of a technician’s time is spent searching for hard‑to‑find parts. If downtime costs around $1,000.00 per hour, every fifteen‑minute hunt adds roughly $250.00 in downtime per event. Repeat that a few times per week across a year and you are looking at hundreds of thousands of dollars burned on top of the physical cost of the parts themselves. SafetyCulture and LLumin both highlight that when essential parts are missing or hard to find, maintenance gets delayed, repairs become chaotic, and overall operational efficiency erodes.

The safety implications are even more serious. MCE Automation points out several major risks that come from ineffective parts inventory management. When the right parts are not available, teams are tempted to use incorrect or incompatible substitutes that do not meet OEM specifications, such as swapping a high‑tensile bolt for a weaker one in a high‑pressure system. Missing components also delay critical repairs, encouraging makeshift fixes like patching a splitting hydraulic hose instead of replacing it. Perhaps most worrying, inadequate stock of guards, safety sensors, or lockout and tagout devices can push people to bypass safety protocols altogether.

In short, poor parts availability does not just hurt your balance sheet. It makes people’s jobs harder and more dangerous. A well‑designed emergency stock program, coupled with sound inventory practices, directly reduces these risks by ensuring that safety‑critical and reliability‑critical parts are on hand when needed.

How Emergency Stock Fits with Inventory Optimization

Many organizations treat emergency stock as an exception to inventory optimization, something you hold “just in case” while the rest of your supply chain is lean. That mindset is outdated and expensive. Modern guidance from ABC Supply Chain, Amazon Business, Rockwell Automation’s Plex team, and Salesforce all emphasize that optimization is about balancing service levels and cost, not simply cutting inventory to the bone.

Several key ideas from that body of work are directly relevant to emergency stock programs.

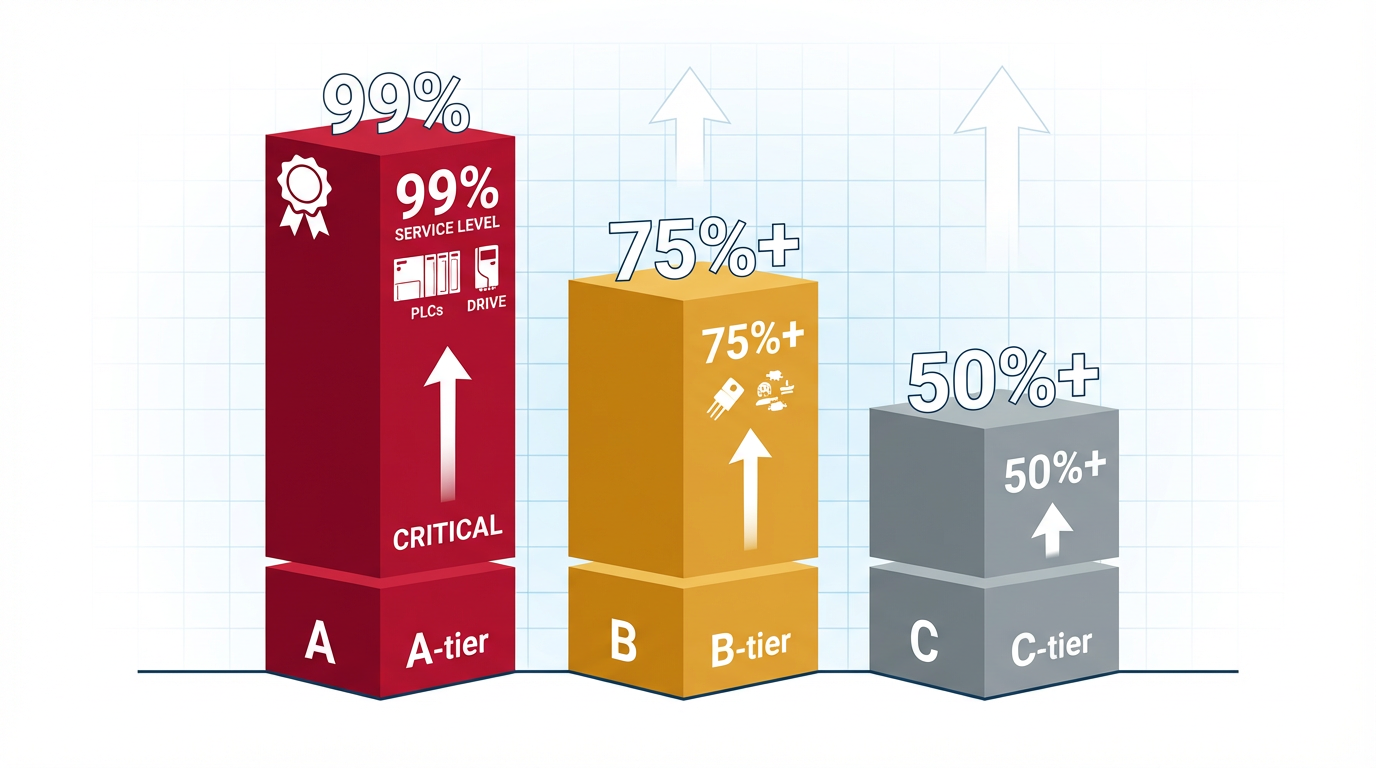

First, ABC analysis. ABC Supply Chain and Rockwell Automation both explain that roughly 20% of SKUs often generate about 80% of results or risk. These A items deserve tighter forecasting, higher service levels, and more attention than low‑impact C items. For automation, critical PLCs, major drives, and primary HMIs usually belong in the A group, while many commodity connectors live in B or C.

Second, service level differentiation. ABC Supply Chain stresses that chasing a perfect 100% service rate across the board is unrealistic and financially harmful. Instead, you explicitly accept occasional stockouts on low‑impact C items so you can maintain very high availability for A items without exploding total inventory. Emergency stock programs are essentially a formalization of that philosophy for automation components: you define where you refuse to accept a stockout and invest accordingly.

Third, safety stock as a strategic buffer. Itemit defines buffer stock as protective inventory held to reduce the likelihood and impact of stockouts, and Omniful goes further into how safety stock formulas incorporate demand variability and lead‑time uncertainty. For critical automation components, you do not guess at these buffers. You use historical failure and usage data, plus supplier performance, to set explicit safety stock targets that align with plant risk tolerance.

Finally, automation and analytics. Firecell, DCKAP, Sortly, and Rockwell Automation all describe how real‑time inventory systems, barcodes or RFID, and integrated planning tools turn inventory from a guessing game into a data‑driven process. Emergency stock programs benefit from the same infrastructure: automated tracking, reorder triggers, and dashboards that show you which critical parts are drifting toward shortage or obsolescence.

Far from being at odds with inventory optimization, emergency stock is one of its most important outputs when you design your policies with risk and service level in mind.

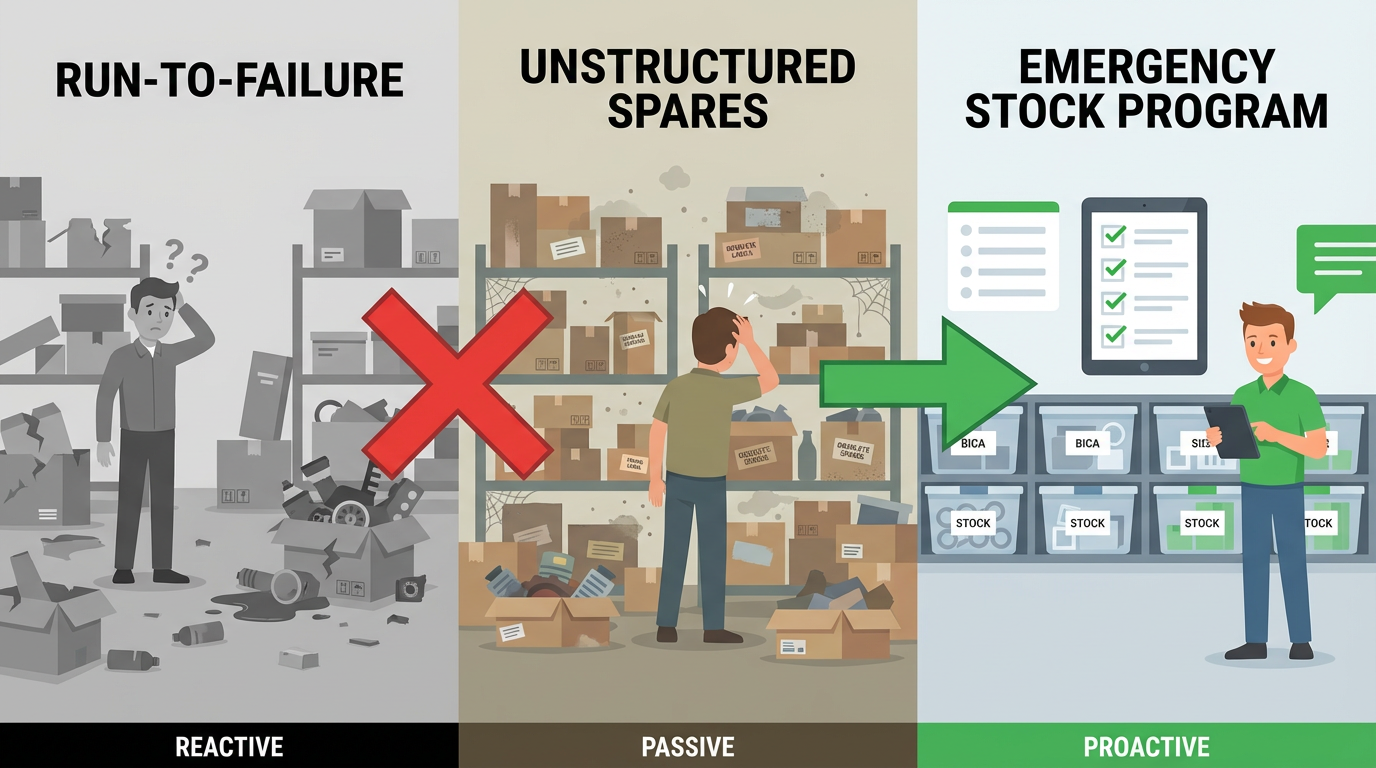

Run‑to‑Failure, Standard Spares, and Emergency Stock Compared

To clarify where emergency stock sits in the bigger picture, it is helpful to contrast it with other common approaches.

| Approach type | Typical behavior in plants | Risk profile and impact |

|---|---|---|

| Run‑to‑failure only | Replace parts only when they break, order on demand, minimal planned inventory | Low carrying cost but high downtime, frequent rush shipping, strong temptation for unsafe workarounds |

| Unstructured spare parts | Keep “whatever seems useful” on the shelf without clear strategy or service targets | Bloated inventory, high carrying cost, lots of obsolete or hard‑to‑find items, still frequent stockouts on key parts |

| Emergency stock program | Predefined list of critical, line‑stopping, long‑lead items with explicit stock policies | Higher availability where it matters most, controlled cost, improved safety and reliability |

In practice, most plants live somewhere between the second and third columns. The goal of the work described in this article is to move you firmly into that third column and keep you there.

Designing an Emergency Stock Program: A Practical Framework

Start with Real Failure Risk, Not Catalog Pages

Industrial Automation Co. recommends identifying critical failure points by asking three simple questions. Which machines are single points of failure? Which components have long lead times? Where has unplanned downtime actually occurred over the last year or two?

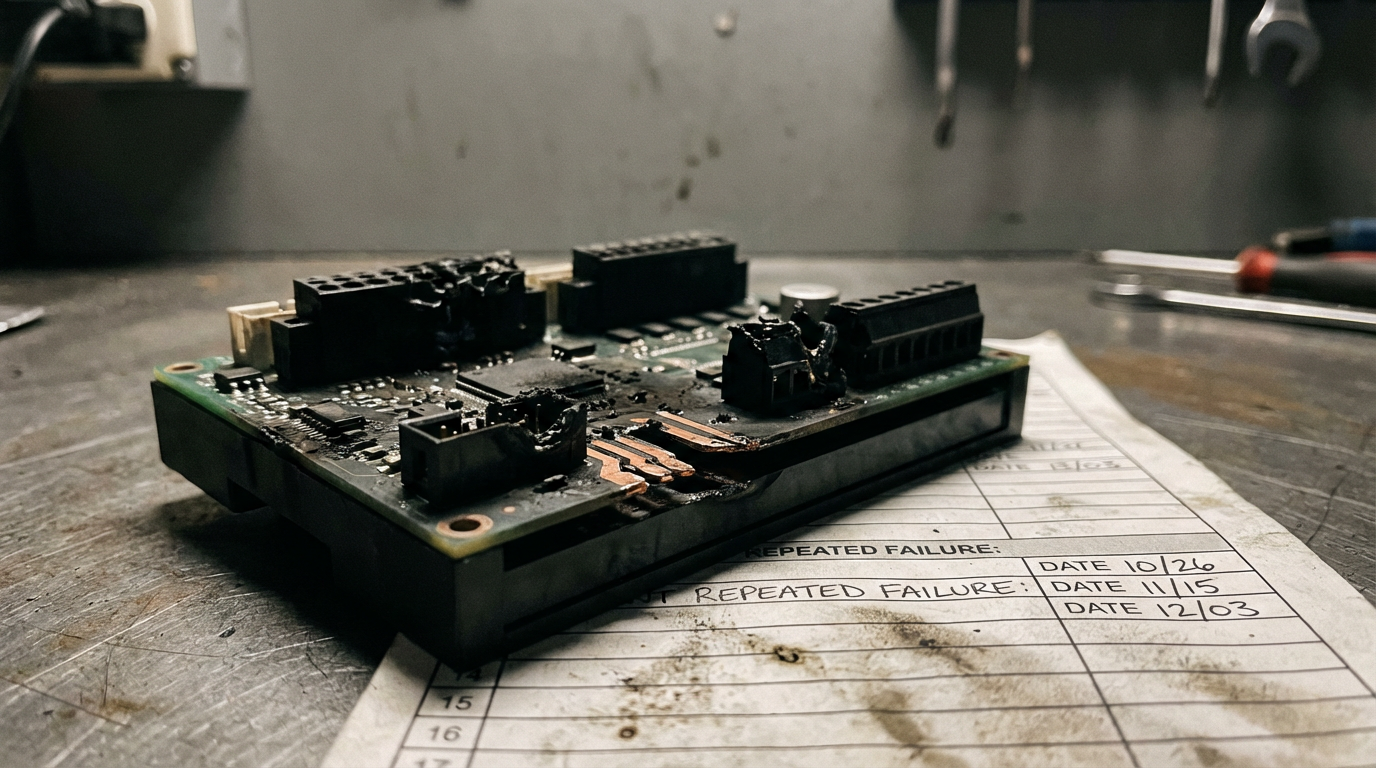

LLumin and SafetyCulture both emphasize building a clear bill of materials and asset list as the foundation of maintenance inventory management. When you combine that asset structure with maintenance logs from the last twelve to eighteen months, you see quickly which PLC I/O module fails repeatedly, which drive overheats every summer, and which HMI power supply has become a regular troublemaker. A part that has failed before, especially more than once, is a strong candidate for emergency stock because its failure pattern is not hypothetical.

That combination of criticality and real failure history is far more valuable than a guess based on price or physical size. A thirty‑dollar sensor that brings down a bottling line is far more “emergency‑worthy” than a much more expensive specialty motor on a redundant system.

Build a Tiered Criticality Model

Industrial Automation Co. proposes a tiered approach that translates well to emergency stock planning for automation.

Tier 1 parts are line‑stopping items such as main VFDs or servo drives, PLC CPUs, core communication modules, primary HMIs, and key industrial power supplies. If you lose these, the line or the plant is down. For these parts, your emergency stock program should guarantee at least one, and often several, ready‑to‑install replacements, along with any accessories such as brake resistors, HIM modules, or dedicated communication cards needed to make a swap straightforward.

Tier 2 parts are high‑risk but workaround‑possible components, such as non‑redundant I/O modules, auxiliary drives, smaller motors, and certain feedback devices. Losing them hurts, but creative routing, reduced capacity, or manual bypass may keep the plant limping along. For this tier, you still hold stock, but you may settle for lower coverage or greater reliance on fast suppliers.

Tier 3 parts are lower‑impact but useful items such as common sensor cables, relay bases, and terminal blocks. Stocking strategy here is more about avoiding constant nuisance stockouts than protecting against catastrophic downtime.

Salesforce’s overview of inventory types reminds us not to forget MRO supplies that are not sold to customers but keep operations running: tools, safety gear, and consumables that support maintenance. MCE Automation stresses that safety components such as guards and lockout and tagout devices are critical; these belong in the upper tiers, because missing them leads directly to unsafe behavior.

By explicitly defining these tiers and agreeing on them across maintenance, operations, and supply chain, you keep conversations grounded. You are no longer arguing over individual part numbers; you are managing risk by category.

Quantify Lead Times and Supply Risk

Criticality alone is not enough. Emergency stock exists because some items simply cannot be obtained fast enough when you need them. Industrial Automation Co. notes that supply‑chain risks mean some automation parts can take two to eight weeks or longer to arrive, particularly from major brands facing global demand and tariff effects.

Inventory optimization guidance from ThroughPut and DCKAP underscores the importance of understanding supplier reliability, minimum order quantities, and logistics constraints across global supply networks. Bufab describes how even seemingly simple C‑parts like fasteners sit behind complex international supply structures with varied lead times and ordering practices.

For your emergency stock program, you should, at a minimum, record typical and worst‑case lead times for each candidate part along with supplier options. When lead times approach or exceed the maximum tolerable downtime for the assets they support, emergency stock is justified. Where lead times are shorter and local distribution is strong, you may rely more on supplier responsiveness and less on on‑site inventory.

Industrial Automation Co. also recommends balancing OEM loyalty with cross‑compatible, tested alternatives for legacy systems. That might mean qualifying a compatible replacement VFD or sourcing refurbished modules for an older PLC platform. Used properly, this strategy can cut costs by 30% to 50% and shorten effective lead times without sacrificing performance.

Use Data, Not Gut Feel, to Set Stock Levels

Omniful explains several ways to calculate safety stock, from simple average‑usage methods to more advanced approaches that consider the variability of both demand and lead time. The details of the formulas matter less here than the underlying principle: your emergency stock levels should reflect the volatility of demand, the consistency of suppliers, and the service level you are aiming for.

ABC Supply Chain and Amazon Business both emphasize the role of a small set of key performance indicators in guiding inventory decisions. For emergency stock, two metrics are particularly useful. Fill rate measures how often you can provide the required part from stock when asked. Inventory turnover indicates how many times you use or replace that stock over a given period. For Tier 1 items, you aim for extremely high fill rates, fully expecting that turnover might be low. For lower tiers, you want higher turnover and are willing to accept occasional stockouts.

Fiix, LLumin, and WorkTrek all advocate using digital systems, not paper or gut feel, to track part usage and failure history. When you can see that a particular PLC CPU has failed twice in twelve months, that you waited six weeks for a replacement, and that the line involved produces high‑margin product, it becomes straightforward to justify a backup unit on the shelf. When you see a part that has not moved in five years in a plant that no longer uses that platform, slow and obsolete stock management guidance from ABC Supply Chain tells you it is time to retire or redeploy that item.

The key is to set emergency stock targets explicitly, document the logic, and revisit the numbers regularly, rather than simply hoping that “one on the shelf” is always enough.

Standardize, Label, and Make Parts Findable

Even the best emergency stock policy fails if technicians cannot locate the parts quickly. Fiix reports that a significant slice of technician time is lost to searching for parts; each quarter‑hour hunt for a missing drive or module adds measurable downtime cost. SafetyCulture and WorkTrek highlight the same challenge: inaccurate records and disorganized stores create delays and confusion.

Several best practices emerge from the research. Every emergency stock item should have a unique identifier, a clear description, and standardized naming. SafetyCulture recommends robust tagging and coding so that parts are easy to track and avoid duplication. WorkTrek and LLumin stress the value of centralized, well‑labeled storage locations, with critical and high‑use items placed in easily reachable areas and their locations recorded in a CMMS or inventory system.

Firecell, Sortly, and DCKAP show how barcodes, QR codes, or RFID tags tied to inventory software provide real‑time visibility into locations and quantities. For plants with multiple sites, Fiix and LLumin encourage standardizing processes and maintaining visibility across facilities so critical parts can be transferred between locations when suppliers are constrained or lead times are long.

If you claim to have emergency stock but technicians still have to call three people and walk half a mile of warehouse aisles to find it, you do not truly have an emergency program. You have expensive clutter.

Integrate Emergency Stock with Maintenance and Projects

Maintenance inventory management is most effective when it is tightly linked to maintenance planning. LLumin defines maintenance inventory management as the strategic oversight of spare parts, tools, and materials needed to perform maintenance and repairs, with goals that include reducing unplanned downtime and emergency repairs.

To make emergency stock work in this context, you should link critical parts to specific assets and preventive maintenance tasks in your CMMS or work order system. When a drive replacement is scheduled on a key line, the system should be able to reserve the emergency spare or trigger a replenishment order immediately after it is used. Fiix and AdvancedTech both highlight the importance of tracking parts usage in work orders to improve forecasting and budgeting.

AdvancedTech also points out that new machinery needs to be included in the spare parts plan from the outset. Early failures or “growing pains” on new equipment can be particularly damaging to production schedules. When you commission a new line, part of the project closeout should be defining the emergency stock list and buying those parts before the first production run, not after the first failure.

Automate Tracking and Replenishment Without Overbuilding Stock

Manual or judgment‑based inventory systems tend to be inaccurate and reactive. Rockwell Automation’s Plex group notes that growing warehouse sizes and complex supply chains have made real‑time data and automation increasingly critical. Firecell, DCKAP, Sortly, and FinallyRobotic all emphasize that automated inventory systems and robotics can cut errors, provide real‑time visibility, and scale with demand more easily than manual processes.

For emergency stock, you do not need a lights‑out automated warehouse to see benefits. Three capabilities make a big difference. Real‑time inventory tracking ensures that the on‑hand quantity of each emergency item is accurate after every issue or receipt. Automated replenishment triggers can create purchase requests or alerts when stock falls below minimum levels tailored to each tier. Analytics and reporting highlight parts that are nearing obsolescence, have not moved for years, or consistently cause rush orders despite nominal stock targets.

Amazon Business and DCKAP both argue for connecting inventory tools with procurement and ERP systems so that purchasing decisions reflect actual usage rather than spreadsheets managed in isolation. When your emergency stock program sits on the same data foundation as the rest of your inventory, you can optimize it with the same rigor.

Pros and Cons of Emergency Stock Programs

Like any powerful tool, emergency stock can help or hurt depending on how you use it.

On the plus side, Industrial Automation Co. stresses that having the right emergency parts on hand can turn what would have been days or weeks of downtime into a quick repair. Plants can avoid panic buys, rush shipping charges, and risky workarounds. MCE Automation’s safety analysis shows that ready access to OEM‑specified parts and safety components reduces the pressure to improvise unsafe fixes. Customers benefit from more reliable deliveries, and operations teams feel supported rather than exposed.

The downsides emerge when emergency stock becomes a synonym for “order two of everything.” Fiix reminds us that carrying excess inventory is expensive once you factor in storage, administration, and capital cost. Omniful warns that overusing safety stock ties up money, raises holding costs, and increases the risk of obsolescence or spoilage. ABC Supply Chain describes slow and obsolete stock as a persistent drain on both space and capital, requiring ongoing identification and cleanup.

The lesson is straightforward. An emergency stock program works best when it is anchored by clear criticality tiers, data‑driven stock levels, and regular reviews for slow‑moving items. When you treat it as a disciplined risk‑management tool instead of an emotional reaction to the last failure, you capture the benefits without creating a parts graveyard.

Common Mistakes I See in Plants

Across different industries and regions, the same patterns show up again and again.

One common issue is letting emotion dictate the emergency list. After a painful failure, teams sometimes put every part from that area into “must‑stock” status indefinitely, even when the root cause has been fixed or the asset has been replaced. Over time, these knee‑jerk decisions accumulate into bloated shelves. ABC Supply Chain and ThroughPut both emphasize the importance of ongoing review and rationalization to prevent this kind of slow drift.

Another mistake is focusing only on “hero parts” like large drives and CPUs while ignoring the accessories that make replacements possible. Industrial Automation Co. specifically calls out HIM modules, braking resistors, wiring harnesses, backup memory cards, communication adapters, and cooling fans and filters as overlooked items that often delay drive or controller replacements. A spare VFD without the correct interface hardware or cabling is, in practical terms, not a spare.

Plants also regularly underestimate the importance of safety and MRO items. MCE Automation’s analysis shows how lack of guards, safety sensors, or lockout and tagout devices pushes people toward risky shortcuts. Salesforce reminds us that tools and other MRO supplies are essential for operational continuity even though they are never shipped to customers. Emergency stock programs that focus solely on production electronics miss this dimension.

Finally, many organizations fail to standardize part numbers and practices across sites. Fiix and LLumin both see multi‑site companies where each plant runs its own storeroom, often stocking the same critical parts under different descriptions. The result is duplicated inventory, inconsistent coverage, and missed opportunities to share emergency stock between locations when supply chains are tight.

All of these issues are avoidable when you anchor the program on shared data, shared standards, and regular cross‑functional review.

A Practical Example: Packaging Line Emergency Stock

Consider a packaging line driven by several VFDs, controlled by a PLC, and supervised through a line HMI. Maintenance logs over the last year show two unplanned shutdowns due to a failed primary drive, each resulting in half a day of lost production and significant overtime. Supplier records show that replacement drives for this frame size typically arrive in four to six weeks, with longer delays during peak season.

Applying the framework described earlier, you would classify the primary drive, PLC CPU, and main HMI as Tier 1 emergency items. Each would have at least one fully configured backup in the storeroom, along with a tested configuration backup for the PLC and HMI. Associated accessories like brake resistors, communication adapters, and necessary cabling would be stocked in quantities sufficient to support at least one complete replacement.

Secondary drives and critical I/O modules might fall into Tier 2, with one spare each, while common photoeyes and generic cables might be Tier 3 with coverage based on normal consumption rather than emergency risk. Using plant downtime estimates and Fiix’s guidance on carrying costs, you can quickly show that the annual cost of this emergency stock is tiny compared to the cost of even a single extended outage.

Over time, work order data from the CMMS and usage history from the inventory system let you refine these levels. If a particular module never fails and lead times shorten, you might downgrade its tier. If a supplier’s performance degrades and lead times stretch, you might increase safety stock on affected items. The program evolves with real conditions instead of remaining stuck in the assumptions of the day it was created.

FAQ

How is an emergency stock program different from normal spare‑parts inventory?

Normal spare‑parts inventory covers the broader set of components needed for routine maintenance and occasional repairs across all assets. Emergency stock, by contrast, is a tightly defined subset focused on parts whose failure would create unacceptable downtime or safety risk and that cannot be obtained quickly enough when needed. Research from ABC Supply Chain and Industrial Automation Co. shows that this subset is usually a small fraction of total SKUs but carries a disproportionate share of operational risk, which is why it deserves explicit policies and funding.

How many units of a critical part should I keep in emergency stock?

There is no universal answer, but the principles are clear from Omniful, Fiix, and other inventory experts. You start by estimating the maximum tolerable downtime for the asset, the typical and worst‑case supplier lead times, and the historical rate and variability of failures. A simple approach multiplies average usage during lead time and then adds a safety buffer proportional to variability and the service level you want. For extremely critical components with long lead times and few alternatives, many plants choose to hold at least two fully functional spares, especially when the downtime cost per hour is very high compared to the carrying cost of additional units.

How often should we review and adjust our emergency stock list?

Omniful cautions that “set and forget” is a formula for trouble. Best practice is to review emergency stock at least quarterly, and immediately after major changes such as new equipment, supplier shifts, or significant process changes. ABC Supply Chain recommends continuous tracking of slow and obsolete stock, while Fiix and LLumin advise using regular inventory and usage reports to highlight items that no longer justify emergency coverage. The goal is to keep the list aligned with current assets, current risks, and current supply‑chain realities, not the plant configuration of years past.

Closing

In complex automated plants, hope is not a strategy. An emergency stock program for critical automation components, built on clear criticality tiers, solid inventory data, and disciplined review, turns last‑minute firefighting into manageable, predictable risk. When you treat that program as part of a broader, optimized inventory strategy rather than a pile of “just in case” parts, you protect your people, your uptime, and your capital all at the same time.

References

- https://abcsupplychain.com/optimize-reduce-inventory/

- https://www.autostoresystem.com/insights/9-steps-to-avoid-stockouts-with-warehouse-automation

- https://www.finallyrobotic.com/post/the-essential-guide-to-automated-inventory-management

- https://firecell.io/optimizing-stock-management-with-automation-a-comprehensive-guide/

- https://itemit.com/how-to-manage-an-inventory-shortage-and-prevent-stockouts/

- https://www.omniful.ai/blog/safety-stock-benefits-best-practices-calculation

- https://safetyculture.com/topics/spare-parts-management

- https://www.simplyfleet.app/blog/efficient-parts-inventory-management

- https://worldclassind.com/the-role-of-technology-in-modern-inventory-management/

- https://www.zenventory.com/blog/the-ultimate-guide-to-emergency-inventory-management

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment