-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Benefits of Factory Sealed PLC Modules for Industrial Applications

As someone who has spent years backing up production teams on plant floors, I have learned that most control problems are not about fancy algorithms. They are about keeping relatively simple hardware alive in tough conditions. Factory sealed PLC modules are one of those unglamorous choices that quietly decide whether your line runs all week or spends it in fault.

This article looks at what “factory sealed” PLC modules really are, how they fit into modern automation architectures, and when they earn their premium. I will draw on both field experience and the kind of guidance you find in references from AutomationDirect, Electrical Engineering Portal, CTI Electric, Balaji Switchgears, and others focused on PLC reliability and installation practice.

What Do We Mean by Factory Sealed PLC Modules?

When I say “factory sealed PLC modules,” I am talking about PLC hardware in which the electronics are fully enclosed and protected by the manufacturer, rather than sitting as open cards in a ventilated panel.

In practice, this usually means the module has a molded or metal housing, gasketed covers over terminations, and conformal coated or potted electronics inside. Some of these products are marketed as rugged, on-machine I/O blocks, often with ingress protection along the lines of IP65 or IP67. Industry coverage of robust PLCs, such as material summarized from QIDA Automation and Lintyco, highlights these protection levels as a way to keep dust and water out under normal industrial operation.

This is different from the traditional rack-mounted card inside a climate-controlled cabinet. With a conventional rack system, the panel is your environmental barrier and each I/O or communication card is relatively exposed, relying on air circulation for cooling. With factory sealed modules, the environmental barrier is designed into the module itself.

The sealed approach shows up in several forms.

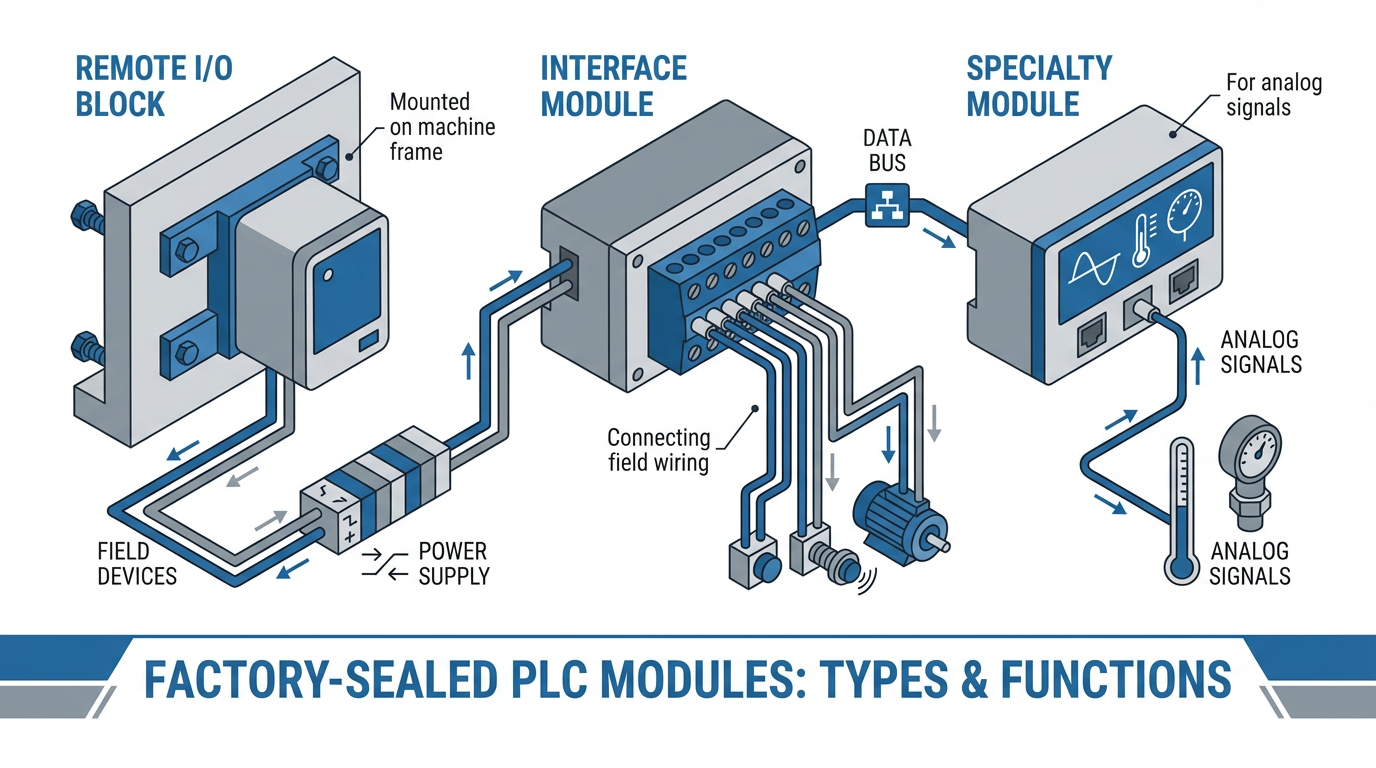

You see sealed remote I/O blocks bolted straight to machine frames, sealed PLC interface modules acting as translators between the PLC and field wiring, and sealed specialty modules such as high-isolation analog interfaces. In all cases, the goal is the same: protect electronics from the environment so you can keep the logic simple and reliable.

Why PLC Modules Matter in Modern Automation

Before looking at sealed versus open, it is worth reminding ourselves why PLC modules are central to modern industrial automation.

Across the sources in your research set — from AutomationDirect’s PLC Handbook through articles by Balaji Switchgears, Breval Consulting, and Empowered Automation — there is a consistent picture. A PLC is a rugged industrial computer designed to read inputs, execute a user program, and drive outputs in a continuous scan cycle. Discrete inputs read switches and sensors; analog inputs read process variables; outputs drive solenoids, contactors, drives, and similar equipment.

Compared with relay logic or general-purpose PCs, PLCs have several properties that matter here:

They are built for harsh environments, with solid-state architectures, protective housings, and good immunity to noise and vibration. Several sources, including Balaji Switchgears and Empowered Automation, emphasize that PLCs are expected to live for decades in industrial conditions, often with operating temperature ranges spanning from well below freezing into very warm plant-floor temperatures.

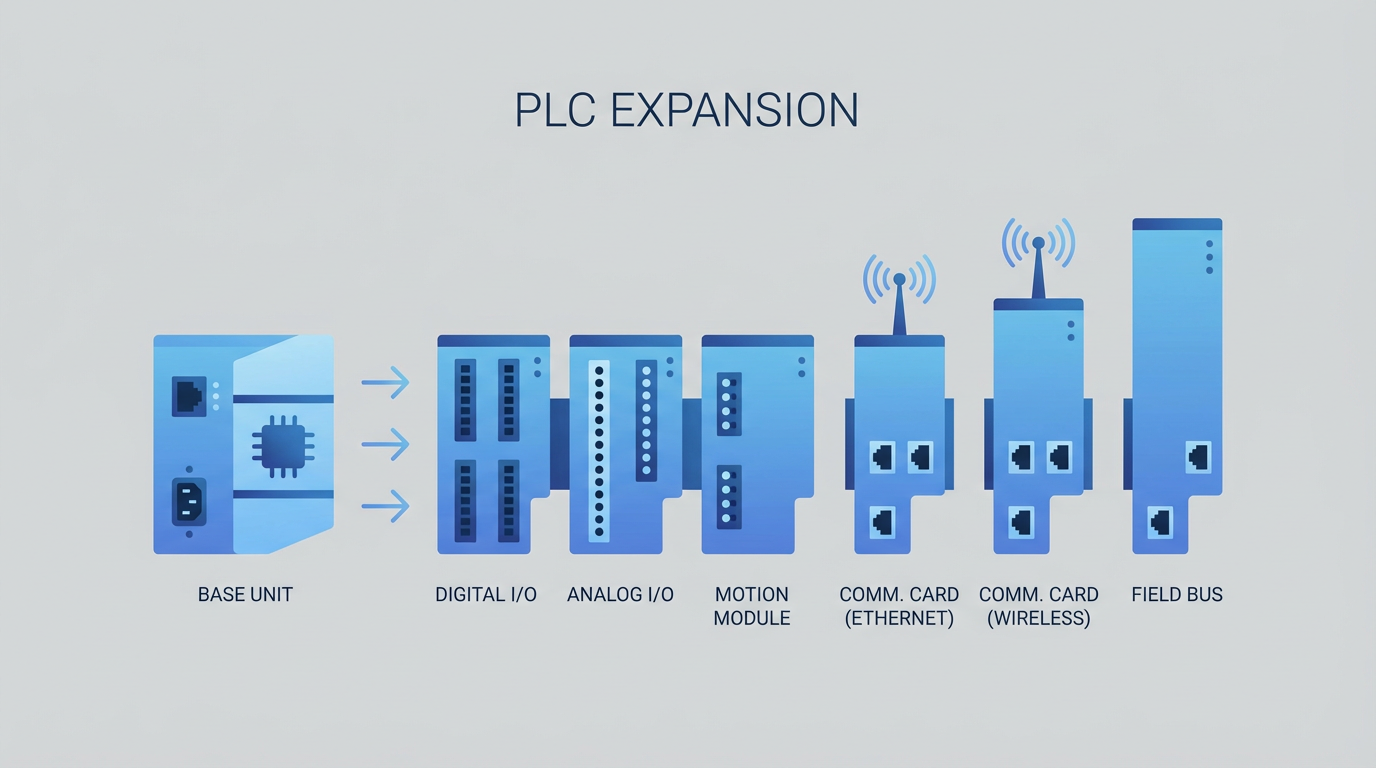

They are modular and scalable.

As documented in AutomationDirect and Maple Systems guidance, you can start small and add I/O modules, specialty cards, and communication interfaces as the plant grows.

They simplify maintenance. AIAutomation and others note that modular hardware and built-in diagnostics make it practical to swap a module rather than rebuild a whole system.

Factory sealed modules are the next step in this progression. They take the rugged, modular PLC concept and push it closer to the process: closer to washdown zones, outdoor equipment, and noisy motor control centers.

Environmental Protection and Reliability

In most plants I work with, the first justification for factory sealed PLC modules is environmental protection.

General literature on PLC reliability, such as QIDA’s work on PLC advantages and several application-oriented sources like Lintyco and Empowered Automation, makes the same point in different words. PLCs are successful because they tolerate temperature swings, humidity, dust, vibration, and electrical noise better than consumer or office-grade equipment.

Sealed modules extend that robustness to places where even a good NEMA panel struggles. In food and beverage packaging, for example, Lintyco describes PLC-controlled packaging lines that must endure frequent cleaning, exposure to fine powders, and varying temperatures. Instead of relying on a distant cabinet and long cable runs, sealed on-machine modules can live right at the equipment, with housings designed to resist moisture and contaminants. Industry examples cited by QIDA show PLC hardware operating at temperatures from well below freezing up to roughly 160°F and at high humidity levels approaching saturation, with ingress protection that keeps dust and spray out. Sealing the module helps maintain that performance in real-world use, where door gaskets and cabinet filters do not always receive perfect maintenance.

From a reliability standpoint, this matters because moisture, dust, and chemical vapors are the enemies of electronics. Once they get onto boards and into connectors, intermittent faults begin to appear: analog drift, digital inputs that chatter, and communication links that drop out whenever local humidity spikes. A properly sealed module reduces those ingress paths. Combined with conformal coated boards and robust connectors, this enables the kind of mean time between failures that QIDA reports for modern PLC hardware, with typical figures above one hundred thousand hours of operation.

In short, sealed modules shift the reliability bottleneck away from environmental contamination and back toward normal wear, which is far easier to manage through planned maintenance.

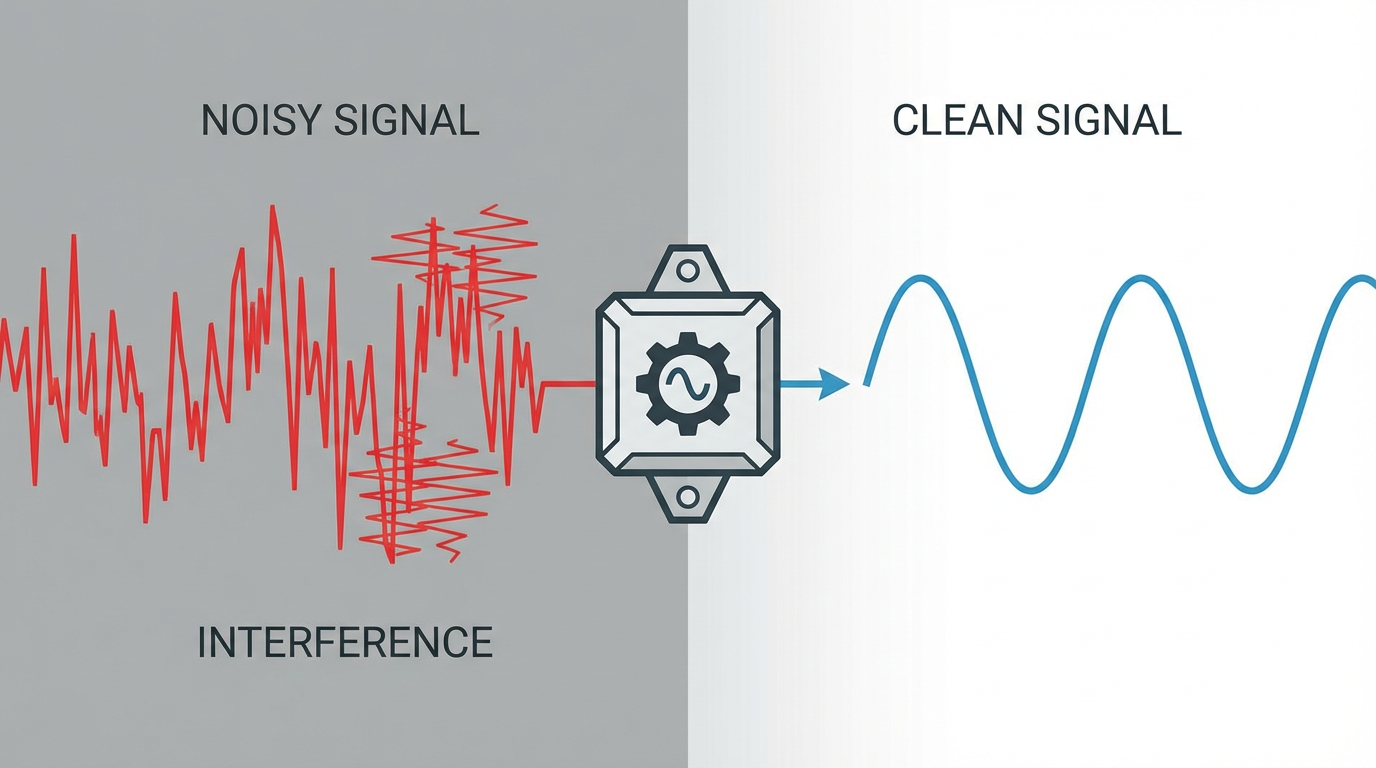

Electrical Isolation and Noise Immunity

The second key benefit arises from how sealed modules are often built around high-quality isolation and signal conditioning.

AOSI Terminals describes PLC interface modules as translators between the PLC brain and field devices, handling signal conversion, electrical isolation, amplification, and filtering. Typical isolation levels in such modules range from roughly 1,500 to 3,000 V. These units protect PLC electronics from surges, ground loops, and noise generated by motors, drives, and welding equipment.

When these interface functions are factory sealed into a dedicated module, you get a known, tested insulation system rather than a patchwork of terminal blocks, relays, and homegrown protection circuits in the panel. That matters in electrically harsh environments like large motor rooms, heavy welding bays, or long pipeline runs.

From a practical integrator’s perspective, strong isolation and noise immunity translate directly into fewer nuisance trips and safer fault behavior. Inputs no longer misread due to induced noise when a large motor starts, and output stages are less likely to be destroyed by a field wiring short or surge. AIAutomation and AutomationDirect both stress that PLCs outperform traditional relay panels in noisy environments; sealed, isolated interface modules push that robustness further by building protection into the module itself.

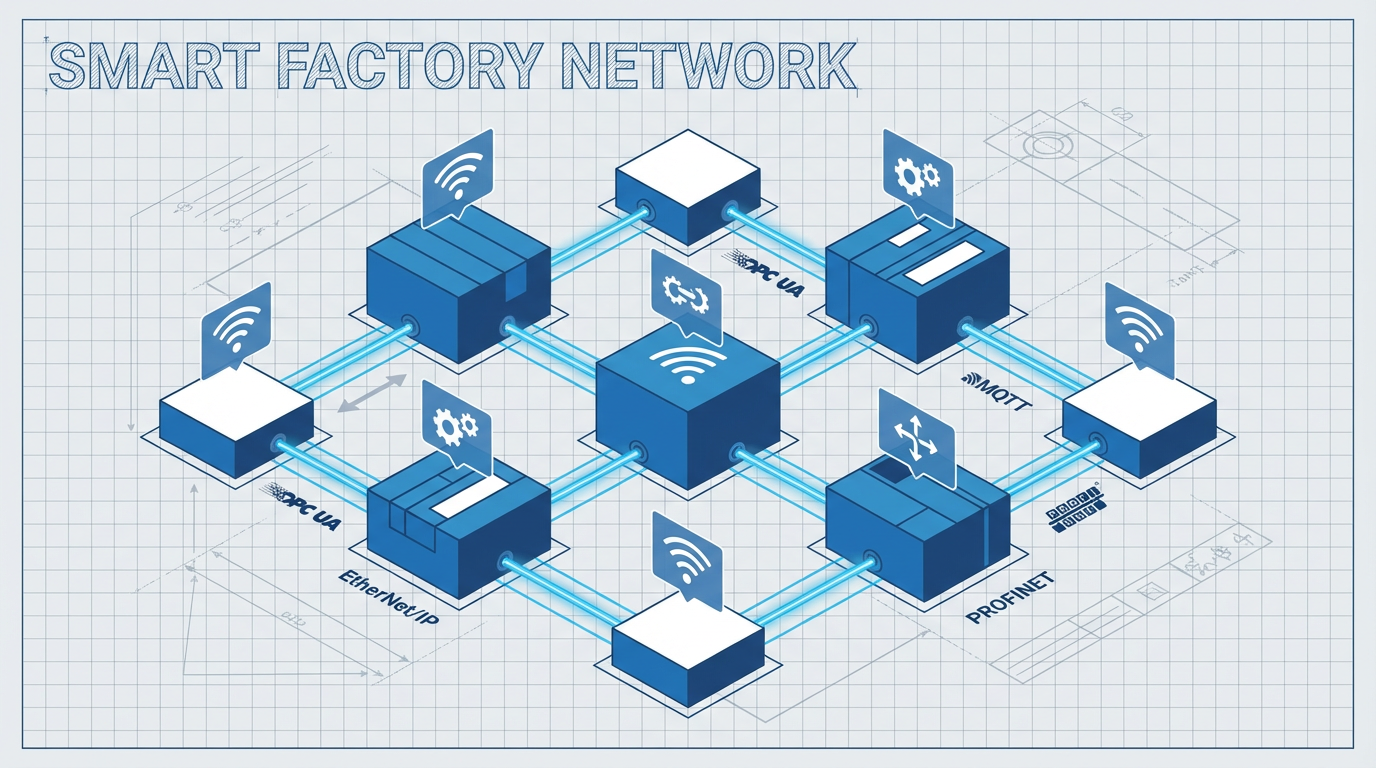

This is especially valuable in plants moving toward smart factory architectures where PLCs, drives, and sensors are heavily networked.

As CTI Electric and similar sources on smart factories explain, high connectivity brings more opportunities for electrical noise and transient events. Sealed, isolated PLC modules act as gatekeepers, cleaning and protecting signals before they reach the control logic.

Installation Speed and Lifetime Cost

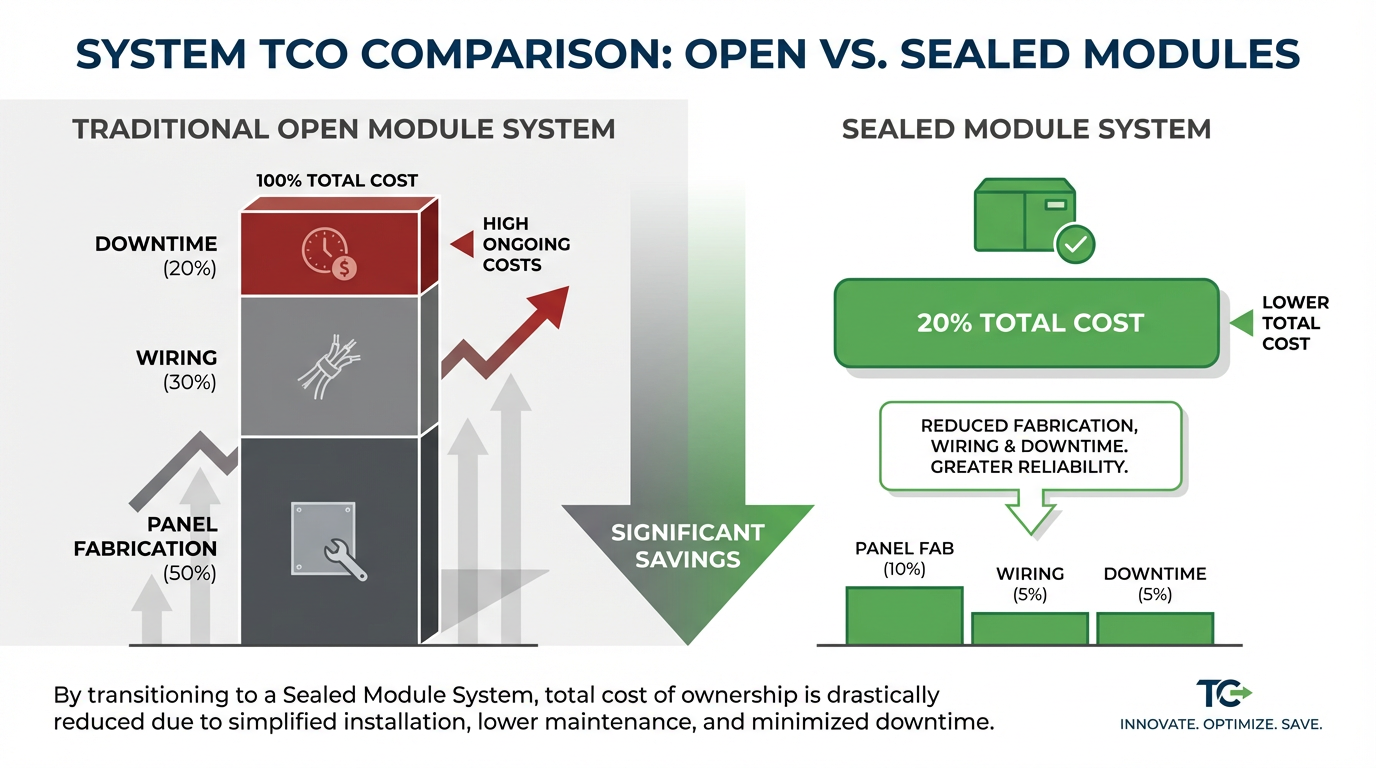

There is no getting around the fact that factory sealed PLC modules often carry a higher unit price than bare cards. The question is whether they pay that back in engineering time, installation labor, and long-term operating cost.

The broader PLC literature in your notes is quite clear that PLC-based automation typically earns its keep over the life of the system. Balaji Switchgears, Breval Consulting, and others describe how PLC automation reduces downtime, simplifies changeovers, and improves troubleshooting, even when upfront capital is higher than relay panels or bare minimum controllers.

Factory sealed modules build on that story in several ways.

First, they reduce panel complexity. Instead of designing a large cabinet full of terminal blocks, relays, interface boards, and wiring ducts, you can mount sealed I/O blocks closer to the field devices. That shortens cable runs and reduces the amount of copper you pull across the plant. ModernPumpingtoday and AutomationDirect both recommend remote I/O and networked modules as a way to avoid long cable bundles and large centralized cabinets. Factory sealed, on-machine I/O is an implementation of exactly that guidance.

Second, they cut project risk around wiring errors. When a sealed module integrates functions like signal conversion, isolation, and power distribution, your electricians are dealing with fewer terminations and simpler wiring diagrams. That shows up on startup: less time ringing out miswired points, more time validating actual process logic.

Third, they lower the cost of failures. Instead of diagnosing down to board level in a hostile environment, a technician can swap an entire sealed module. Diagnostic guidance from AutomationDirect and Empowered Automation stresses the value of modular hardware that can be replaced without disturbing the rest of the system. In harsh environments, sealed modules make “swap and go” realistic without worrying that the replacement will immediately suffer the same contamination damage.

In many of the upgrades I have supported, once you add up panel fabrication, plant cabling, commissioning time, and unplanned downtime over a few years, the higher purchase price of sealed modules becomes a relatively small piece of total cost.

Safety and Compliance Benefits

Safety functions increasingly reside inside PLC systems. Sources like AutomationDirect’s controller selection guidance and Breval’s discussion of PLC benefits highlight how PLCs implement safety interlocks, emergency stops, and safe shutdown sequences.

Factory sealed modules support that safety mission in a few ways.

First, they help ensure that safety-related I/O remains reliable. If a safety input from a light curtain or safety mat passes through a corroded terminal in a damp cabinet, all the safety certifications in the world do not matter. A sealed module with protected contacts and proper isolation reduces the chance that the safety channel is compromised by contamination.

Second, they simplify compliance with equipment standards for specific industries. Food and beverage packaging, pharmaceutical filling, and chemical processing all combine aggressive cleaning or chemical exposure with strict safety regulations. Lintyco and Empowered Automation both describe PLC-controlled packaging and process systems that must maintain high accuracy and repeatability while meeting regulatory requirements. Using sealed modules aligned with appropriate enclosure ratings and isolation levels makes it easier to provide documentation to safety inspectors and auditors that your control hardware meets both environmental and safety expectations.

Finally, sealed modules support controlled failure modes. As QIDA notes, modern PLCs employ watchdog timers, redundant processors, and fast response to detected faults, with safety-certified controllers helping plants significantly reduce workplace incidents. Sealed modules reinforce those safety strategies by making it more likely that the hardware supporting protective logic behaves predictably over time, instead of drifting due to moisture, dust, or chemical attack.

Data Quality and Predictive Maintenance

One of the big themes in modern PLC practice is data. PLCs are no longer just relay replacements; they are data acquisition engines feeding SCADA, MES, and predictive maintenance tools. This is clear in sources like CTI Electric’s coverage of smart factories, Empowered Automation’s discussion of PLC data logging, and QIDA’s description of PLC-driven predictive maintenance that cuts maintenance costs and downtime across dozens of plants.

Factory sealed modules pull their weight here by preserving sensor accuracy and signal stability in tough conditions.

AOSI’s overview of PLC interface modules emphasizes functions such as amplification, isolation, and EMI filtering. When these functions are integrated into a sealed module operating near the sensors, the analog signal arriving in the PLC is cleaner and more stable. That reduces false alarms and improves the fidelity of trends used by predictive maintenance systems.

QIDA describes how vibration and thermal data feeding PLC-based analytics can predict failures such as bearing wear with high accuracy. That only works if analog inputs behave consistently over months and years. Sealed modules that resist contamination and corrosion reduce drift and intermittent connections, which in turn keeps your predictive models trustworthy.

From an integrator’s viewpoint, this is more than a theoretical advantage. Any time you try to implement predictive maintenance on a line where analog wiring runs through corrosive or wet areas into a distant panel, you see anomalies that have nothing to do with the equipment condition. Moving analog front-end electronics into sealed modules near the source helps cut through that noise and makes your data worth the storage and analysis effort.

Scalability and Smart Factory Integration

Scalability is another recurring theme in your sources. AutomationDirect, Modern Pumping Today, Balaji Switchgears, RL Consulting, and others all stress that PLC systems should be selected with expansion in mind. Plants rarely stay static; new equipment, sensors, and data requirements arrive every budgeting cycle.

Factory sealed PLC modules fit naturally into scalable architectures.

On the hardware side, modular sealed I/O blocks or sealed interface units allow you to bolt on additional points as needed. Modern Pumping Today and AutomationDirect recommend leaving spare I/O and designing expansion paths. Doing so with sealed modules often means leaving space on machine frames or mounting rails near the process rather than in a remote panel. Adding more I/O becomes a localized activity rather than a major panel rebuild.

On the network side, sealed modules with support for common industrial communication protocols — such as those cited across sources by AutomationDirect, RL Consulting, and CTI Electric, including Ethernet-based protocols and fieldbuses — make it easier to extend your network to new skids or remote locations without compromising on environmental protection.

That matters for smart factory programs. CTI Electric describes smart factories as highly connected environments where PLCs are central to real-time coordination and data flow. Sealed PLC modules let you extend that connectivity into challenging spaces, such as outdoor utility equipment, wastewater areas, or washdown zones, without building climate-controlled rooms for every new network node.

Trade-Offs and Limitations

Factory sealed modules are not a silver bullet. They solve some problems and introduce others, and a pragmatic design has to acknowledge both.

Serviceability is the first trade-off. With an open card in a panel, a skilled technician can sometimes repair damage at component level or at least inspect the board visually. With a factory sealed module, the standard practice is to replace the entire unit. For many plants this is acceptable and even preferred, but it changes how you think about spare parts. You stock whole sealed modules rather than just generic relays or terminal blocks.

Thermal management is the second issue. The PLC installation guidance you referenced from Electrical Engineering Portal and similar manuals warns about providing clearance and airflow around PLC racks. Typical instructions call for a few inches of spacing between racks, good ventilation, and limits on cable lengths to maintain signal integrity. Sealed modules, especially those potted or heavily coated, can run warmer because their housings do not dissipate heat as freely and they are often mounted in less ventilated locations on machinery. That means you must respect the manufacturer’s derating curves, mounting orientations, and environmental limits more carefully. You still gain protection against contaminants, but you must avoid cooking the module.

Flexibility is the third consideration. A large rack in a panel gives you freedom to rearrange I/O slots and add specialty modules in almost any order recommended by the vendor. Sealed modules are more fixed in capability; a particular housing might provide a certain combination of digital and analog points and perhaps a specific communication port. Expanding or changing that mix later sometimes means adding an additional sealed module rather than simply sliding a new card into an existing rack.

Finally, there is cost. Many of the selection guides in your notes, including Simcona’s and Rabwell’s PLC selection advice, caution against over-specifying controllers and hardware. Factory sealed modules typically carry a premium, and they are not necessary for every environment. In clean, climate-controlled process rooms, standard rack modules in a well-built panel often provide an excellent balance of cost and performance.

The trick is to apply sealed modules where their benefits outweigh these trade-offs.

Where Factory Sealed PLC Modules Make Sense

In practice, sealed PLC modules shine in a few recurring settings.

One is food, beverage, and packaging. Lintyco and QIDA both document PLC-controlled packaging machinery subject to frequent washdowns, fine powders, sticky residues, and tight quality requirements. Mounting sealed I/O and interface modules directly at the machine — in areas where spray and cleaning chemicals are common — reduces the risk of ingress that would quickly defeat a traditional panel. You still use centralized PLC CPUs and higher-level networking, but the front-line I/O that touches the process is sealed.

Another is outdoor and utility equipment. CTI Electric’s discussion of smart factories and industrial connectivity includes references to utilities and energy systems where environmental exposure is severe. Pump stations, remote valves, and outdoor conveyors often see rain, temperature swings, and condensation. In those settings, sealed remote I/O or interface modules can live in small field boxes or even on exposed structures, reducing the need for large, heated buildings just to protect control hardware.

A third is harsh process areas such as chemical plants and wastewater operations. Empowered Automation and QIDA note that PLC control is widely used in water treatment and similar facilities. These environments often combine corrosive atmospheres with high humidity. Factory sealed PLC modules, along with appropriate enclosure ratings and protective coatings, help keep control electronics reliable over long periods in such conditions.

A fourth is high-availability production lines with tight uptime requirements. When a line is expected to run around the clock and small outages are costly, the combination of rugged housing, built-in isolation, and simple module replacement makes sealed units attractive. QIDA’s statistics on significant reductions in accidents, failures, and maintenance costs with modern PLC hardware illustrate what is at stake. While those figures are not specific to sealed modules, sealing is one of the design approaches vendors use to hit that level of performance in harsh duty.

Practical Selection and Specification Guidance

If you are evaluating sealed PLC modules for a project, it helps to work through a simple but disciplined thought process. The selection advice in sources like AutomationDirect, Modern Pumping Today, RL Consulting, Simcona, and Maple Systems can be adapted to this sealed-module decision.

Start by characterizing the environment. Identify where moisture, washdown, dust, chemicals, or outdoor exposure are unavoidable. Map those zones to candidate I/O locations. Any area where you would be uncomfortable mounting an open board or relay panel is a candidate for sealed hardware. Use your facility standards and environmental data rather than optimism; PLCs are tough, but they are not magic.

Then match I/O and signals to module capabilities. AOSI’s interface module guidance is a useful reminder that different applications call for different signal-conditioning features: analog conversion, protocol translation, isolation, and amplification. For each field device cluster, determine whether you need simple digital I/O, accurate analog measurement, specialty counting, or a protocol bridge to legacy equipment. Select sealed modules that natively support those requirements rather than stacking extra interface boards.

Next, verify isolation and ratings. In noisy or high-energy environments, confirm that the module’s isolation voltage and noise immunity meet your needs. AOSI cites isolation in the 1,500 to 3,000 V range for industrial interface units; use that as a benchmark when you compare products. At the same time, check ingress protection, operating temperature range, and vibration resistance against your environmental profile. Sources like QIDA’s discussion of PLC ruggedness show that modern PLC hardware can handle wide temperature ranges and significant vibration; your sealed modules should be in the same class.

Plan how you will maintain and replace modules. Because sealed modules are replaced as units, you should define standard spare parts lists, storage conditions, and swap procedures. Align your documentation and backups with this strategy. Southern Electrical’s description of PLC installation and maintenance emphasizes the importance of regular inspection, firmware updates, and backups; sealed modules do not change that, but they influence where and how you perform those tasks.

Finally, think about integration and data flow. CTI Electric’s smart factory overview and Empowered Automation’s description of PLC connectivity show that modern plants depend on reliable data paths between controllers, HMIs, SCADA, and higher-level systems. Ensure that your sealed modules fit into that architecture. Check that they support the industrial Ethernet or serial protocols used in your plant and that their diagnostic data can be exposed to your monitoring tools. One of the hidden advantages of sealed modules is that they often include built-in diagnostics similar to those described by Balaji Switchgears and AutomationDirect for PLCs in general. Make sure you actually use that information.

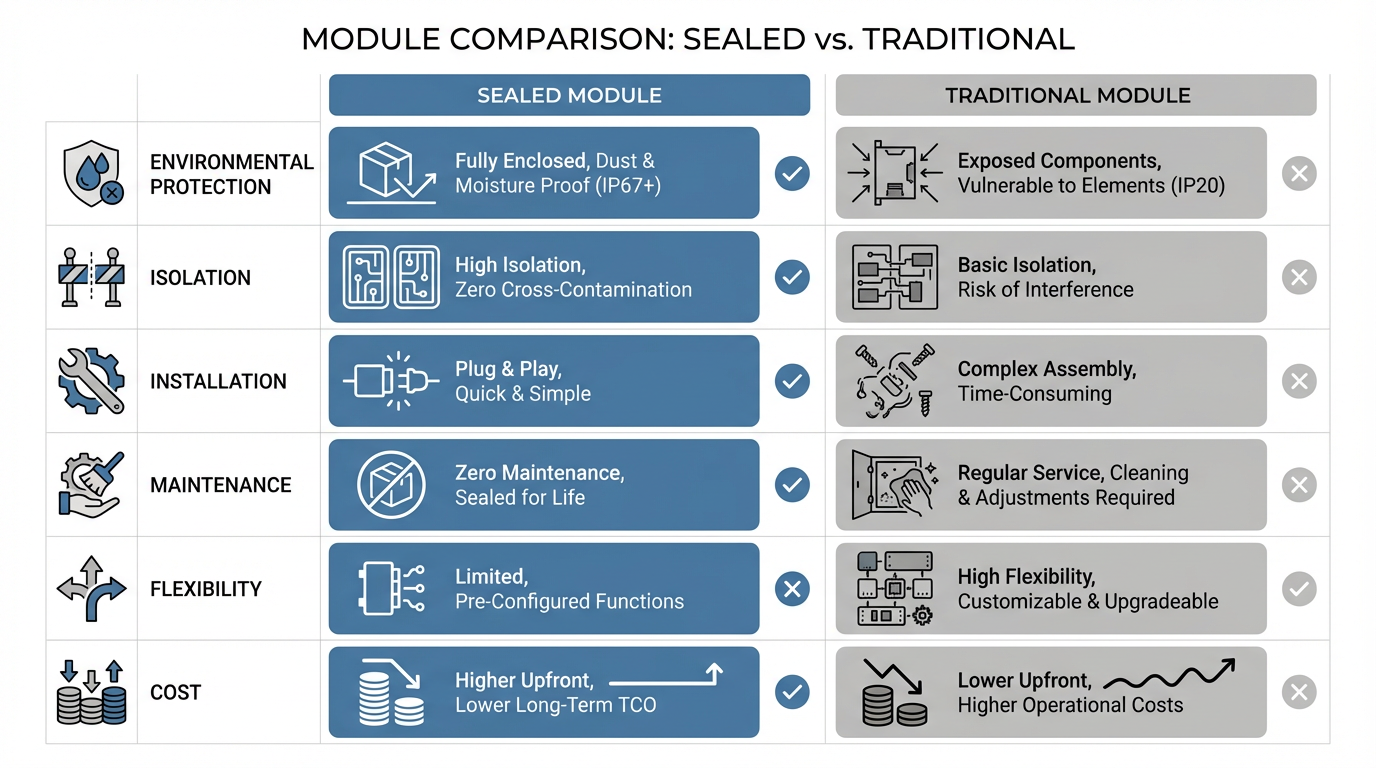

A concise way to think about the trade-offs is to compare sealed and traditional options along a few key dimensions.

| Aspect | Factory Sealed PLC Module | Conventional Open Module in Panel |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental exposure | Electronics protected by housing and sealing | Protected primarily by cabinet and installation quality |

| Noise and isolation | Often integrates isolation and conditioning close to field devices | Isolation often distributed among cards, relays, and wiring |

| Installation and wiring | Shorter field runs, localized wiring, simpler panels | Centralized wiring, longer runs from process to panel |

| Maintenance approach | Replace module as unit, rely on built-in diagnostics | Mix of module swap, relay replacement, and component-level diagnosis |

| Flexibility and expansion | Expansion via additional sealed modules with fixed function sets | Expansion via reconfiguring racks and adding cards in larger cabinets |

| Upfront cost | Higher cost per I/O or interface point in most vendor ecosystems | Lower unit cost; higher panel, wiring, and long-term maintenance burden |

This is a general comparison based on common industry practice and the characteristics described across your PLC references. Specific vendor offerings will differ, but the pattern tends to hold.

Brief FAQ

When are factory sealed PLC modules worth the premium?

They are most compelling when the environment is harsh enough that you do not trust a standard panel and open cards to stay clean and dry over time. Washdown, outdoor, corrosive, or very dusty locations are the classic examples. They are also a strong option when uptime is critical and you want technicians to restore service by swapping one part rather than diagnosing complex contamination issues inside a cabinet.

Do factory sealed modules replace control panels entirely?

They reduce your dependence on large centralized panels but do not eliminate panels. You still need safe power distribution, terminations, and places to mount PLC CPUs, network switches, and safety hardware. In many smart-factory architectures, you end up with smaller backbone panels in benign locations and sealed modules or sealed remote I/O out at the equipment.

Are sealed modules harder to integrate with existing PLC systems?

Not if you select them deliberately. The same controller selection references you have — from AutomationDirect, RL Consulting, and others — emphasize communication compatibility and system-level architecture. As long as your sealed modules support the PLC vendor’s recommended networks and I/O architectures, they behave like any other module from the controller’s perspective. The main differences are mechanical and environmental, not logical.

At the end of the day, factory sealed PLC modules are not about chasing the latest buzzword. They are about making standard, proven PLC architectures survive in places where cabinets and open cards have always struggled. If you match them carefully to your environment, signals, and maintenance strategy, they become one of those unremarkable design decisions that keep your line running while everyone else wonders why your plant is so calm.

References

- https://aiautomation.org/pros-and-cons-of-plcs-in-industrial-automation/

- https://pimassetsprdst.blob.core.windows.net/assets/apc_Original/33/48/27143348.pdf

- https://www.empoweredautomation.com/the-role-of-automation-plc-in-modern-manufacturing

- https://library.automationdirect.com/choosing-factory-automation-controller/

- https://www.automationmag.com/the-modular-plc-current-applications-and-where-the-technology-will-be-applied-next/

- https://balajiswitchgears.com/key-benefits-of-implementing-plc-based-automation/

- https://ctielectric.com/how-smart-factories-use-plcs-to-boost-efficiency/

- https://www.lintyco.com/how-plc-control-systems-revolutionize-industrial-automation/

- https://maplesystems.com/10-things-to-consider-when-choosing-new-plc/?srsltid=AfmBOoqoo57e90q_o2hRHDNDFgcl3F7_gMCeS_IvXq5kgZhhS-BUa4Gl

- https://modernpumpingtoday.com/how-to-choose-an-industrial-automation-controller/

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment