-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Fanless Embedded Controllers for Harsh Environment Applications

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

Why Harsh Environments Destroy Ordinary Controllers

When you push control hardware out of the control room and into the real world, the environment stops being a background detail and becomes the main design constraint. Oil fields, mining trucks, rail cars, food processing lines, remote radar towers, and outdoor motion systems all have one thing in common: they chew through office‑grade electronics.

Harsh‑environment sources such as Promwad, EE Times, and Sealevel all describe the same set of stressors. Temperatures swing from deep cold to well above 185°F. Humidity and salt spray condense on boards. Dust and abrasive particulates settle into every opening. Vibration and shock come from engines, rough roads, and machinery. Strong electromagnetic fields and, in some sectors, radiation overlay everything. In some aerospace and high‑altitude cases, reduced air pressure even removes normal convection, so heat has nowhere to go.

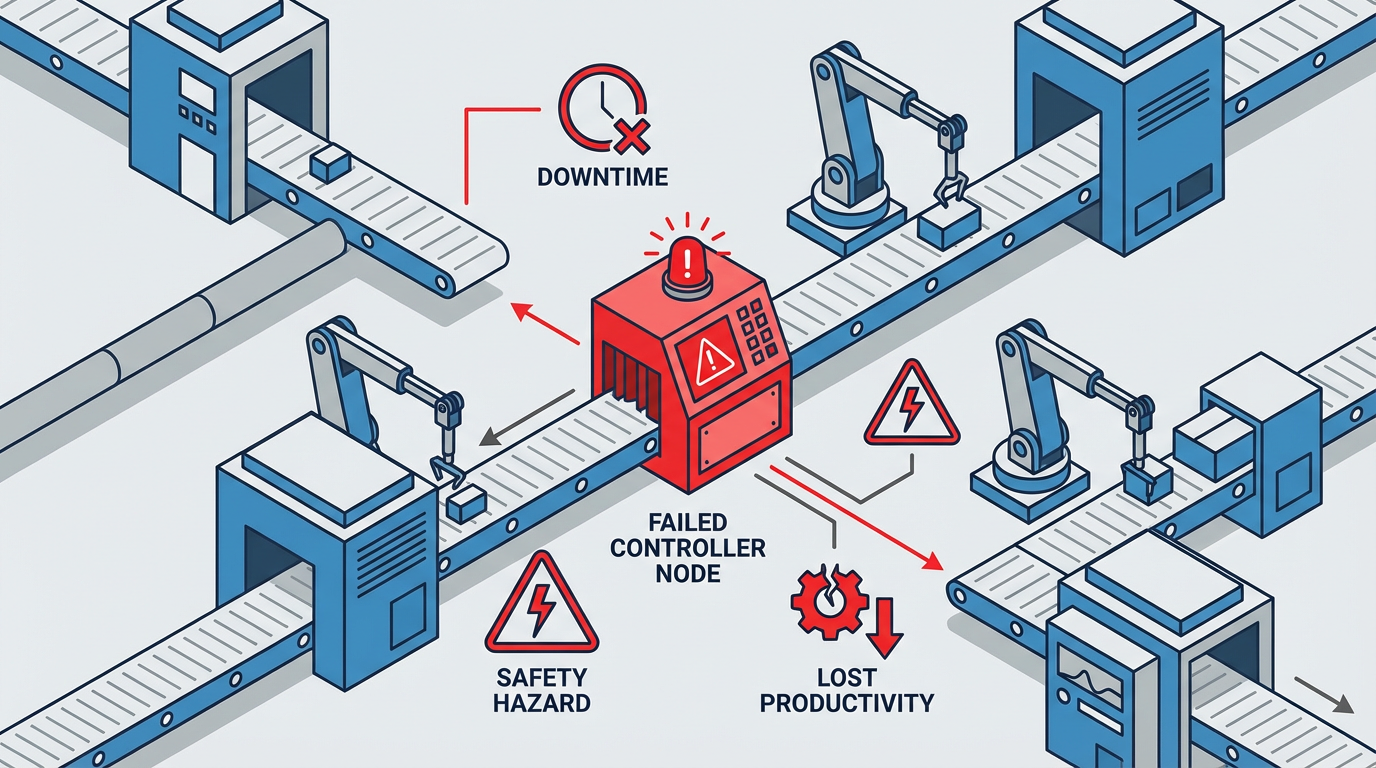

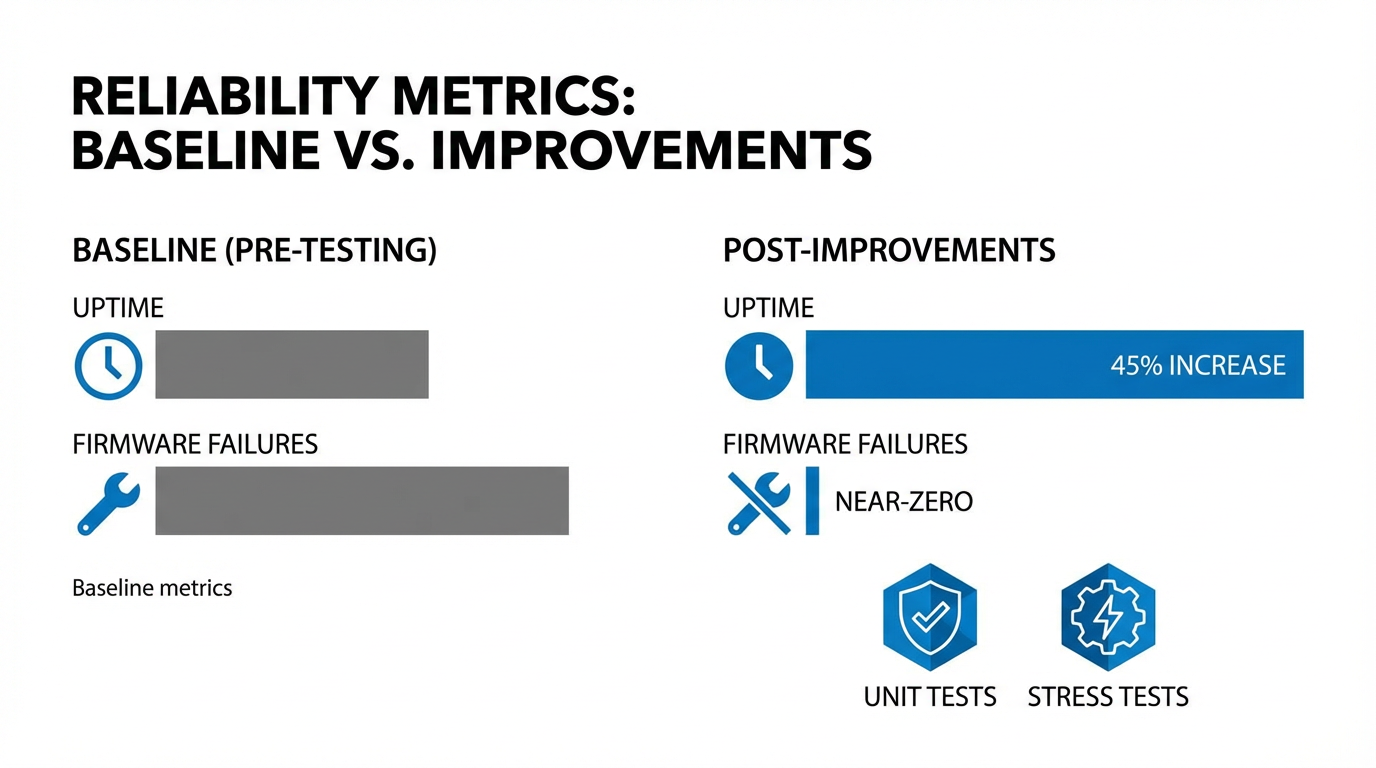

Field failures in these environments are not just inconvenient. Promwad points out that they cause unplanned industrial downtime, on‑site repairs, warranty exposure, and safety hazards. Fidus shows in a medical case study that improving test discipline on embedded systems increased uptime reliability by about forty‑five percent and nearly eliminated firmware‑related failures. In remote or mission‑critical deployments, a dead controller means lost production, missed service levels, and sometimes a safety incident investigation.

After a few decades integrating control systems into everything from mobile machinery to clean‑in‑place food plants, I have learned that the only sustainable strategy is to design for the worst credible environment from day one. That is exactly where fanless embedded controllers, built on industrial or military‑grade design practices, earn their keep.

What “Fanless Embedded Controller” Really Means

Vendors and marketers use the term loosely, so it helps to be precise.

In the context of harsh industrial environments, a fanless embedded controller is essentially an industrial PC or embedded computer designed as a sealed, passively cooled control node. Sources such as SinSmart, Plant Engineering, Premio, and Sealevel all converge on the same picture. These systems typically offer:

A rugged housing, often aluminum or steel, that doubles as a heat sink and can be mounted in cabinets, on vehicles, or directly on equipment.

Industrial‑grade components, not consumer parts, with temperature ratings that commonly span from about –40°F up to around 185°F, and in some automotive or military components up to roughly 257°F as EasyIoT highlights.

Passive, fanless cooling where heat is conducted into the enclosure and out to the environment via the housing, heat spreaders, and thermal interfaces. Promwad stresses that outdoor and dusty designs favor conduction cooling and heat pipes over fans.

Sealed or ingress‑protected I/O, such as M12 connectors for Ethernet, CAN, or serial lines, as described by Premio and Plant Engineering.

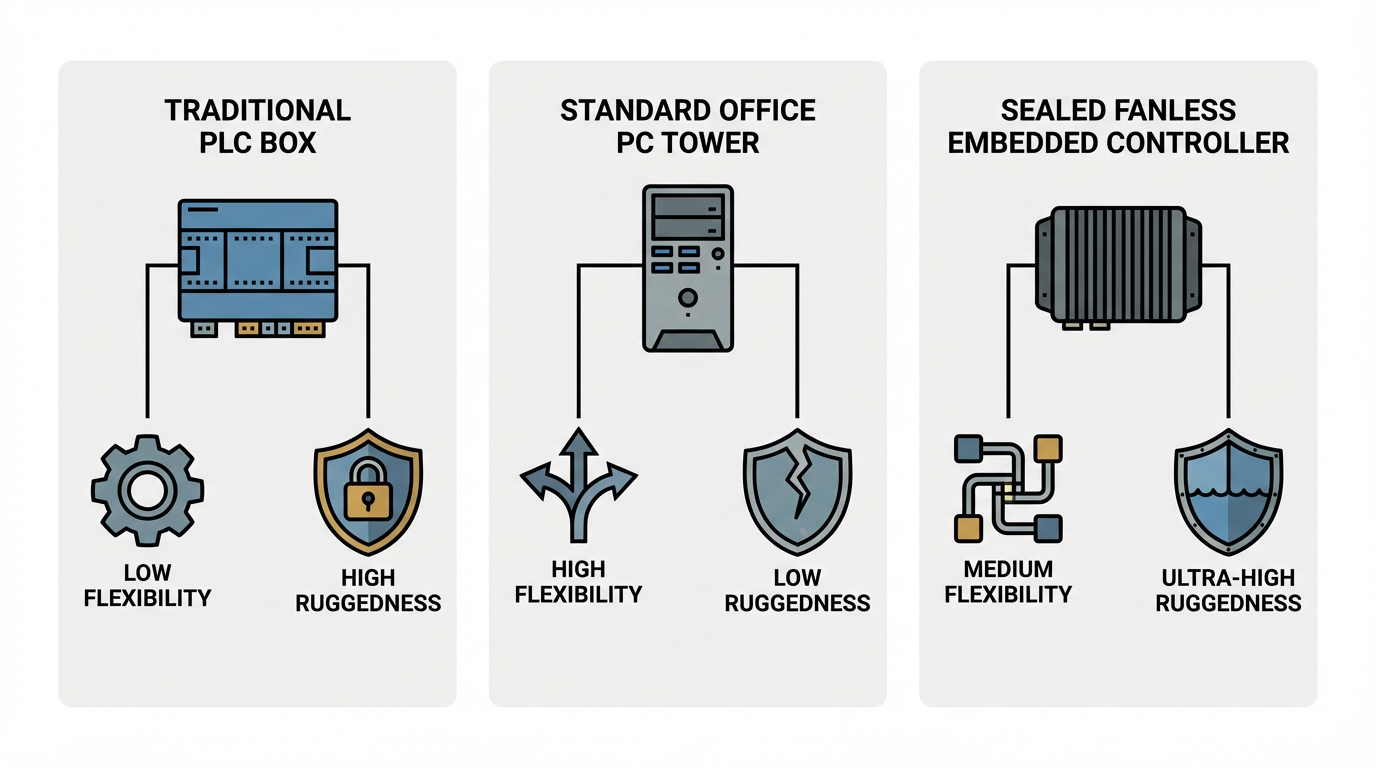

In many ways, these controllers are the edge computers of modern automation: more flexible than a traditional PLC, more rugged than an office PC.

They sit between low‑level microcontroller‑based devices and high‑level servers, running real‑time control, data acquisition, analytics, and communications at the edge.

Environmental Threats Fanless Controllers Must Survive

Promwad’s harsh‑environment guidance lists the big four: temperature, moisture and corrosives, dust and particulates, and vibration and shock. Extended extremes can include EMI, radiation, and vacuum or high altitude. These same categories show up in embedded design articles from Arshon, Embedded.com, and Vorago.

Temperature is usually the first killer. Thermal cycling induces mechanical fatigue. Early failures show up as solder joint cracks, delamination, and trace lift, especially if boards use standard FR‑4 and marginal solder metallurgy. Embedded.com notes that above roughly 392°F, polyimide‑based boards and solder masks quickly degrade, which is why ceramic or other high‑temperature substrates dominate in extreme designs. Even at far lower temperatures, repeated swings between –40°F and 185°F stress every interface inside a package and across the PCB.

Moisture, condensation, and corrosive atmospheres attack copper, tin, and exposed pads. Promwad and Arshon both emphasize conformal coatings and potting to keep salt spray, chemical vapors, and humidity off the circuitry. Ingress protection ratings such as IP67 and IP68 define how dust‑tight and water‑resistant the enclosure is. Promwad notes that IP67 enclosures are completely dust‑tight and withstand immersion in water to about 3.3 ft for roughly half an hour, while IP68 goes deeper under conditions defined by the manufacturer.

Dust and particulates clog fans, abrade connectors, and, if conductive, can bridge traces. This is one reason so many outdoor and mobile designs go fanless and fully sealed. As Premio and SinSmart both point out, eliminating fans removes both a moving failure point and a forced‑air dirt path.

Vibration and shock fatigue solder joints, crack components, and shake loose cables. Promwad and Arshon recommend using thicker PCBs, underfill for BGAs, low‑profile components, and secure mechanical mounting with multiple standoffs. Standards such as IEC 60068‑2‑27 for shock and IEC 60068‑2‑64 for random vibration, cited in Plant Engineering’s description of the emPC‑CXR controller, give engineers a common test language when qualifying boxes for rail or mobile use.

Once you accept that all of these threats are present, the appeal of a sealed, fanless, mechanically hardened controller becomes clear. The rest of the story is how you design and select those controllers so they actually deliver.

Inside a Fanless Controller: Design Priorities

Thermal Design Without Fans

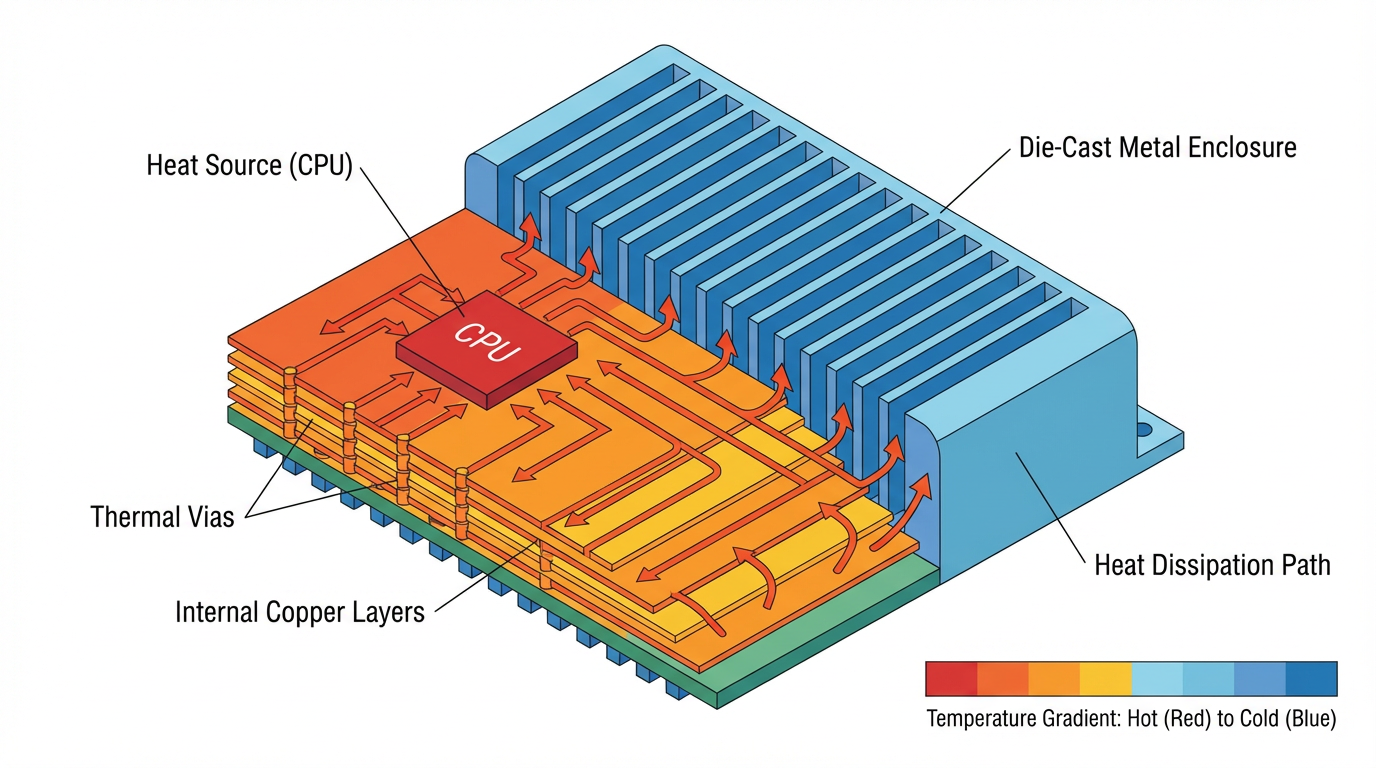

Removing the fan does not remove the heat. It just moves the problem into mechanical and PCB design.

Arshon’s guidance for extreme‑environment electronics is blunt: worst‑case environmental conditions must drive every design decision. That starts with choosing components with wide temperature grades. EasyIoT distinguishes commercial grades around 32°F to 158°F from industrial and military grades stretching from about –40°F up to roughly 185°F or even –67°F to around 257°F. Vorago’s work on high‑temperature microcontrollers pushes the upper bound much further for specialized aerospace and downhole applications, with parts expected to operate as high as around 392°F. Using those components means the silicon keeps working even when the enclosure is hot and convection is poor.

At the board level, Arshon recommends thick copper planes, thermal vias, and copper pours under hot parts to create strong conductive paths into the chassis. Promwad shows the same principle at enclosure scale: bolt power devices directly to metal walls, use heat pipes or thermally conductive potting where needed, and treat the entire housing as a heat spreader. This is exactly what you see in many fanless industrial PCs and in the harsh‑environment emPC‑CXR class of controllers Plant Engineering describes.

There is a trade‑off here. Sealed, fanless enclosures have finite thermal headroom. You cannot simply drop in the highest‑power processor and a discrete GPU and assume conduction will save you. In practice, that means carefully profiling real workloads, using efficient processors where possible, and distributing compute closer to sensors so that no single controller runs excessively hot. EE Times reinforces this theme in the context of autonomous remote systems: every watt saved at the node can be redeployed for other critical tasks such as closed‑loop control.

Enclosure, IP Ratings, and Mechanical Standards

Ingress protection and mechanical robustness are not marketing checkboxes; they are hard constraints if you plan to mount a controller on a vehicle, a rail car, or a washdown production line.

Promwad offers a clear explanation of IP ratings. The first digit covers solids. A six means dust‑tight. The second covers water. Seven means temporary immersion. Nine‑K covers high‑pressure, high‑temperature washdown. Premio’s discussion of IP67 embedded systems focuses on tightly sealed, waterproof and dustproof enclosures, typically fully fanless, with gasketed lids and sealed I/O such as M12 connectors. For more aggressive washdown, Premio’s SIO series touchscreens combine IP66 and IP69K ratings with stainless‑steel housings, designed to survive frequent cleaning in food and dairy operations.

Plant Engineering’s emPC‑CXR example is a good reference point for harsh industrial use. The controller operates across a wide ambient range from roughly –40°F to about 158°F, is housed in a compact chassis around 10.6 in by 7.9 in by 3.2 in, and meets IEC 60068‑2‑27 for shock and IEC 60068‑2‑64 for random vibration. On the transportation side, it complies with DIN EN 50155, which governs electronic equipment in railway rolling stock. Moisture‑proof interfaces and M12 five‑pin connectors that can be wired for CAN bus or serial links finish the package, giving you a box comfortable on a rail car, a vehicle, or a plant skid.

In motion control and mobile automation, Automate’s motion‑control coverage highlights similar patterns. Mining vehicles use embedded computers such as Cincoze’s DX‑1100 in high‑dust, high‑shock, wide‑temperature conditions, while marine applications use rugged systems like Cincoze’s DS‑1200 to handle moisture, salt spray, and vibration on vessels. The common thread is a sealed, mechanically robust enclosure validated to IEC 60068 and often MIL‑STD‑810 for broader shock, vibration, and environmental tests.

The practical takeaway is straightforward. For a harsh‑environment fanless controller, insist on a clear IP rating, named mechanical standards such as IEC 60068‑2‑27 and MIL‑STD‑810 where relevant, and application‑grade standards such as EN 50155 for rail or ATEX and IECEx for explosive atmospheres when you are in oil, gas, or mining.

Electronics, PCB Technology, and Component Choices

Fanless controllers for harsh environments borrow heavily from the playbook used in aerospace and radiation‑tolerant embedded systems.

Arshon and Embedded.com both emphasize material selection. Standard FR‑4 laminates are acceptable for modest industrial conditions, but in high‑temperature or high‑reliability designs, polyimide, PTFE, specialized RF laminates, or ceramic substrates offer better thermal stability and lower expansion. Corrosion‑resistant surface finishes such as ENIG or ENEPIG, mentioned by Promwad, avoid the exposed tin and lead issues that plague unprotected copper.

To handle moisture and contamination, Arshon recommends conformal coatings such as acrylic, polyurethane, and parylene. Promwad adds that these films, typically on the order of a few thousandths of an inch thick, protect against humidity, salt fog, and corrosive atmospheres. For really aggressive environments or full immersion, potting or encapsulation with epoxy or silicone can effectively lock the electronics inside a solid block. The trade‑off, as Promwad notes, is that potting can complicate inspection, repair, and in some cases thermal management, though thermally conductive potting compounds can mitigate the last point.

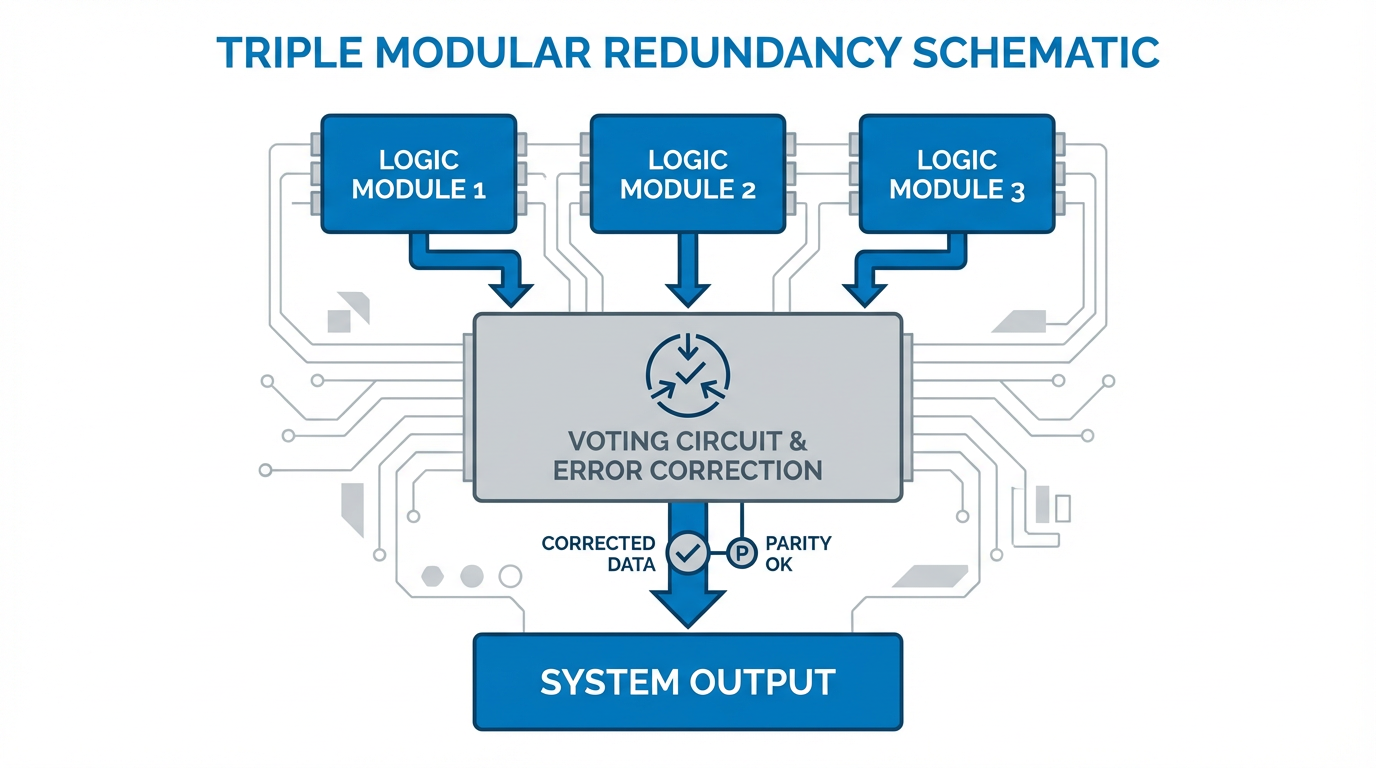

Radiation and ESD are niche concerns in many industrial plants but central in aerospace, nuclear, and high‑altitude applications. Embedded.com outlines how ionizing radiation can cause single‑event upsets and latch‑up in memory and logic. Mitigations include error detection and correction schemes that use parity or error‑correcting codes, triple modular redundancy where three copies of logic vote on the answer, and hardened latches such as dual interlocked storage cells.

Vorago extends this further in space‑grade microcontrollers, combining radiation‑tolerant processes with wide temperature operation and low power, backed by standards such as MIL‑STD‑883 and European space agency specifications.

Even if your fanless controller will never leave the ground, you benefit from the same mindset: select parts qualified for the environment you truly face rather than derating consumer parts beyond their intent. That includes capacitors operated at about half their voltage rating, junction temperatures kept well below maximum, and attention to component mean time between failures.

Power Architecture in Remote Harsh Installs

Power is often the hidden constraint in remote fanless installations.

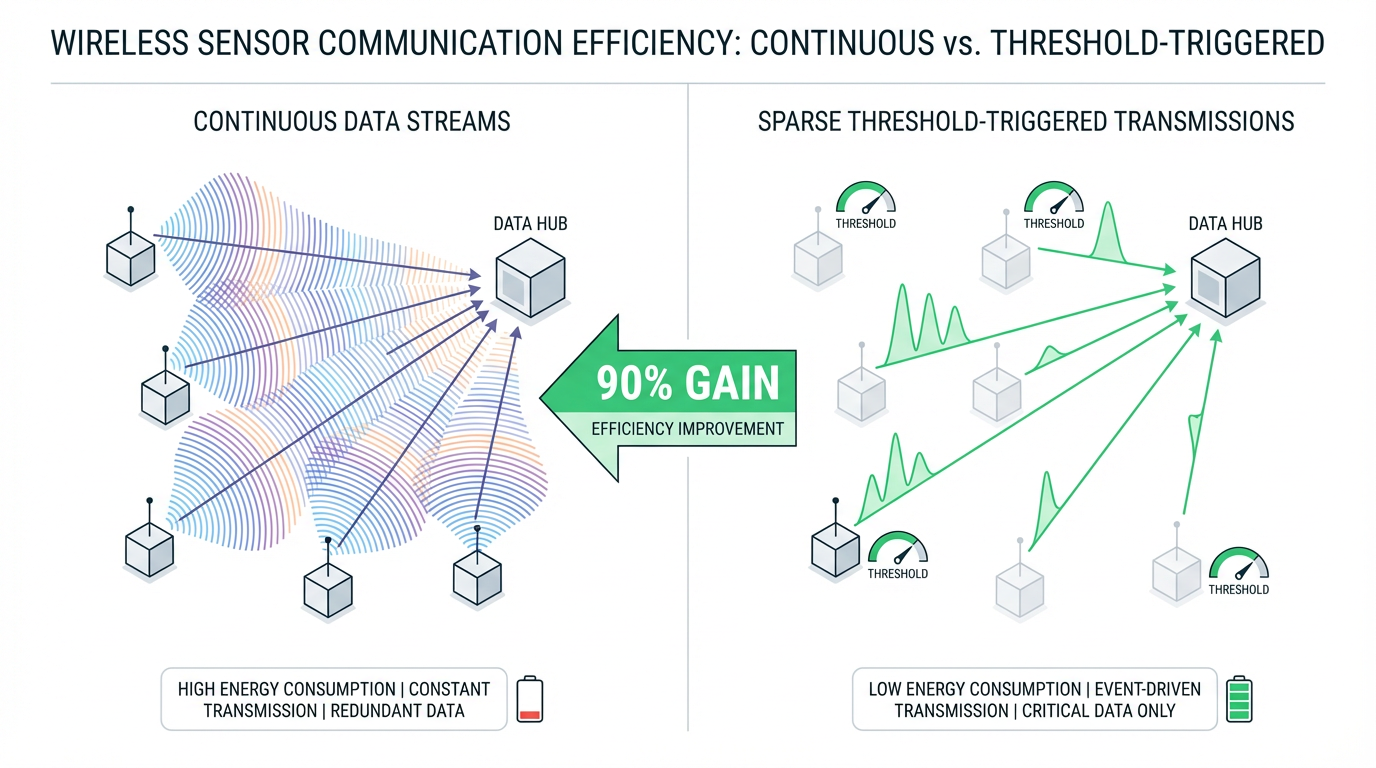

EE Times points out that most extreme‑environment autonomous systems are battery powered, sometimes backed by renewable sources such as solar. Batteries add weight and volume, both at a premium. Designers are forced to trade off the number of sensors, the communication range and frequency, and the sophistication of control algorithms against the available watt‑hours. In one wireless monitoring example, programmable sensor nodes send readings only when a threshold is exceeded and transmit averaged values over a longer interval, which yields about ninety percent better communication efficiency while maintaining effective measurement frequency.

That freed power can be redirected into more demanding functions, including closed‑loop control.

Arshon’s recommendations for power supplies in harsh environments align with this reality. Wide input‑voltage ranges allow a controller to accept typical industrial rails while tolerating sag and surges. High‑efficiency switching regulators are preferred over linear regulators to avoid waste heat. Transient and EMI protection, including transient voltage suppressor diodes, ferrites, and snubbers, guard against spikes from long cables and inductive loads.

Plant Engineering’s emPC‑CXR details reflect these requirements in industrial practice. The controller accepts a wide DC input, roughly 9 V to 34 V, allowing it to run from common plant or vehicle power rails. Premio’s and SinSmart’s industrial PC discussions add that robust systems often support isolated inputs and optional uninterruptible supplies or batteries for ride‑through during brownouts.

In agriculture and environmental monitoring, the STM32‑based greenhouse research paper illustrates another angle. There, low‑power microcontrollers and careful peripheral selection allow a dual‑node monitoring system to run from modest power sources while collecting temperature, humidity, soil moisture, and other parameters. Energy‑aware designs use solar cells and DC‑DC converters to regulate variable inputs into stable charging voltages, underscoring how vital power management is for remote embedded nodes.

For a fanless controller, power design must align with both the worst‑case electrical environment and the worst‑case thermal scenario, because every watt that goes in as heat must escape without the help of a fan.

Software, Control, and Reliability Engineering

Hardware ruggedization is only half of the story. Software and system design decide whether the controller behaves predictably through faults.

Fidus emphasizes that embedded systems live at the intersection of hardware constraints, real‑time deadlines, and long life cycles. Failures can cause safety hazards, regulatory non‑compliance, and costly downtime. Their ventilator case study during a pandemic shows that adding unit tests, static analysis, hardware‑in‑the‑loop simulation, and long‑duration stress tests improved uptime reliability by forty‑five percent and cut firmware‑related failures nearly to zero.

On resource‑constrained controllers, EasyIoT notes that real‑time and control applications benefit from deterministic timing, direct memory access, and in some cases dedicated co‑processors for time‑critical algorithms. When applications grow beyond a certain complexity, real‑time operating systems such as FreeRTOS provide preemptive multitasking, error handling, and hooks for power management.

Promwad and Embedded.com both call out watchdog timers and fail‑safe routines as essential in harsh environments. If noise, radiation, or an unexpected condition locks up the controller, a watchdog must be able to reset it into a safe state. Memory integrity checks using error‑correcting codes or checksums help detect and sometimes correct bit flips caused by EMI or radiation. Over‑the‑air update mechanisms, described in Promwad’s and other harsh‑environment articles, are especially valuable for remote or hazardous locations where physical access is expensive or risky.

Finally, Arshon and Fidus converge on the need for thorough validation. Environmental tests such as thermal cycling, vibration and shock tables, humidity chambers, salt fog, and highly accelerated life tests reveal weaknesses long before deployment. Software‑in‑the‑loop and hardware‑in‑the‑loop simulations allow you to iterate controllers and embedded code under simulated extremes that would be impractical or dangerous to replicate at full scale.

In practice, for a fanless controller in a harsh environment, I treat unattended recovery, remote logging, and structured test coverage as non‑negotiable requirements.

Otherwise, the first brownout or thermal excursion will expose you.

Fanless Versus Fan‑Cooled Controllers in Harsh Environments

Many teams ask whether they really need a fanless solution. A concise comparison helps frame that decision.

| Aspect | Fanless Embedded Controller | Fan‑Cooled Industrial Controller |

|---|---|---|

| Cooling method | Conduction and natural convection through the chassis and heat spreaders, no moving parts | Forced convection using one or more fans to move air through vents |

| Environmental sealing | Typically sealed or IP‑rated enclosures, often IP65–IP67 or higher as described by Promwad and Premio | Vents and fan openings reduce achievable IP rating; additional filters and cabinets required for dust or washdown |

| Vibration and dust tolerance | Better suited to high‑vibration and dusty environments because there are no fan bearings or airflow paths to clog | Fans and open vents are vulnerable to dust ingress and mechanical wear under vibration |

| Maintenance profile | Little to no routine maintenance; SinSmart notes that eliminating fans removes cleaning and replacement tasks, especially valuable in remote sites | Requires periodic fan inspection and replacement; filters clog and must be serviced, which can be difficult in remote locations |

| Compute density and thermal headroom | Thermal envelope often limits peak processor and GPU power; careful workload sizing required | Greater flexibility to dissipate higher thermal loads, allowing denser compute in the same volume |

| Typical sweet spots | Outdoor edge controllers, mobile machinery, rail, marine, washdown environments, explosive atmospheres where ingress protection dominates | Cleaner indoor plants, control rooms, or cabinets where airflow can be controlled and environmental loads are modest |

In harsh settings, the increased reliability and reduced maintenance of fanless controllers usually outweigh their thermal limitations, especially as modern embedded CPUs deliver substantial performance at modest power budgets.

Real‑World Deployment Patterns

The research notes provide several concrete patterns that are instructive when you are selecting or designing a fanless controller.

Transportation and rail are classic harsh environments: constant vibration, temperature swings, and limited access. The emPC‑CXR, highlighted by Plant Engineering, shows what a rail‑ready controller looks like. It is compact enough for tight spaces, runs from roughly –40°F to about 158°F, meets EN 50155 for rail applications, and carries shock and vibration qualifications under IEC 60068‑2‑27 and 60068‑2‑64. Moisture‑proof interfaces and M12 connectors make it comfortable in rolling stock, roadside cabinets, or wayside equipment.

Mining and off‑road vehicles see similar stresses. Automate’s motion‑control article discusses an embedded computer operating around the clock in mining equipment, handling dust, shock, and wide temperatures while fusing sensor data in real time. Such designs rely on fanless, shock‑hardened enclosures and vehicle‑grade electronics to avoid field failures in remote pits.

Marine environments add salt spray and moisture to vibration and shock. Automate describes a rugged embedded system on tuna‑fishing vessels managing real‑time radar and sonar data despite salt, moisture, and electrical disturbances. Again, the system combines wide‑temperature components, sealed housings, and modular I/O suitable for a marine bridge.

Food, beverage, and pharmaceuticals create a different kind of harshness: constant washdown and cleaning chemicals. Premio’s SIO series washdown touchscreens show how IP66 and IP69K stainless‑steel enclosures with optically bonded displays can survive high‑pressure, high‑temperature cleaning while remaining precise operator interfaces. Matching fanless controllers in similar housings lets you bring compute power right into hygienic zones.

Aerospace and defense, as Sealevel explains, add altitude, low pressure, and stringent regulatory requirements. Rugged computers there must handle reduced convection, extreme thermal cycling, and heavy EMI, while being developed under AS9100D quality systems that enforce traceability, configuration control, and counterfeit‑part prevention. While not every plant needs that level of process rigor, the underlying practices—clear documentation, long‑term lifecycle planning, and supply‑chain control—serve industrial projects just as well.

Across all these cases, the pattern is consistent. When the environment is unforgiving and access is difficult, fanless, sealed, standards‑qualified controllers paired with appropriate software practices provide a stable base for long‑term operation.

How to Specify a Fanless Controller That Will Actually Survive

From a systems integrator’s perspective, the most common project failures begin at the specification stage. The hardware looked fine in a catalog, but key environmental or system‑level requirements were never written down.

The starting point is a clear environmental profile. Promwad’s breakdown is a good checklist. Define the realistic extremes for ambient temperature, humidity, and contaminants. Determine whether the controller will see shock events, continuous vibration, or both, and at what levels. Note any exposure to radiation, high altitude, or vacuum if you are in aerospace or nuclear sectors. Align these conditions with component temperature grades from EasyIoT and with enclosure IP ratings and mechanical standards from Promwad and Plant Engineering.

Next, quantify the I/O and networking needs. SinSmart emphasizes that industrial PCs often succeed or fail based on peripheral support. Applications may need serial interfaces such as RS‑232 or RS‑485, multiple Ethernet ports or Power‑over‑Ethernet, CAN bus in vehicles and rail, and GPIO or fieldbus links to existing PLCs. The emPC‑CXR example with configurable M12 connectors for CAN or serial shows how flexible connectors simplify field wiring in harsh conditions.

Compliance and safety standards deserve the same early attention. Promwad and Embedded.com call out IEC 60529 for ingress protection, IEC 60068 and MIL‑STD‑810 for environmental testing, ISO 16750 for road‑vehicle conditions, EN 50155 for railway electronics, and ATEX or IECEx when explosive atmospheres are present. In critical sectors, functional safety standards such as IEC 61508 for industrial systems or ISO 26262 for automotive add their own requirements. If your project touches aerospace, Sealevel’s discussion of AS9100D and FAA and defense program traceability gives a sense of the documentation and process obligations involved.

Finally, plan for lifecycle and testing up front. Fidus’s work on embedded testing and Arshon’s discussion of environmental validation both underline that “test later” is an expensive strategy. Specify environmental and functional tests along with the hardware, including thermal cycling, vibration, humidity or salt‑fog exposure, and long‑duration stress tests where appropriate. Require vendors to share at least high‑level test results and to support your own qualification program.

In practice, I translate all of this into a concise, testable requirements document before touching a vendor catalog. That document drives the selection of fanless controllers, power subsystems, and enclosures, and it becomes the yardstick we use when accepting systems from the factory.

Pros and Cons of Fanless Controllers in Harsh Environments

Fanless embedded controllers are not a silver bullet. They excel under certain conditions and impose real constraints under others.

On the plus side, sealing the enclosure and eliminating fans drastically improves resistance to dust, moisture, and mechanical shock, as described by Promwad, Premio, SinSmart, and Plant Engineering. No fans means no bearings or blades to clog and wear out, which reduces routine maintenance. Fanless designs are quieter and often simpler to integrate mechanically because you do not have to route airflow or maintain filter access. Combined with long‑life industrial components, these attributes raise mean time between failures and lower total cost of ownership, especially in remote or hard‑to‑reach sites.

There are trade‑offs. Passive cooling limits how much heat the controller can safely dissipate. That can constrain CPU selection, especially if you want to run power‑hungry analytics or machine vision at the edge. Conduction‑cooled enclosures may be larger or heavier than equivalent fan‑cooled boxes to provide the necessary surface area. Heavy use of potting or encapsulation, while excellent for vibration and moisture, makes field repair difficult or impossible; failed units are often swapped rather than repaired in place. Upfront hardware costs are usually higher than for commercial systems, a point Sealevel and SinSmart both acknowledge, even though lifecycle costs are lower.

From a project standpoint, the right answer is not “fanless everywhere.” It is to deploy fanless controllers where the environment and access constraints justify them and to size the compute and enclosure to avoid operating at the edge of the thermal envelope.

Implementation Pitfalls and Practical Advice

Several recurring mistakes show up on harsh‑environment projects. The research and field experience behind the sources here suggest pragmatic ways to avoid them.

First, do not treat IP ratings as a catch‑all ruggedness guarantee. Promwad clearly distinguishes between ingress protection, which covers dust and water, and other stressors such as chemicals, UV, and mechanical shock. An IP67 controller may survive immersion but still fail under continuous vibration if it lacks IEC 60068 or MIL‑STD‑810 validation. Always pair IP requirements with mechanical and environmental standards appropriate to your application.

Second, avoid over‑stressing commercial‑grade components. Embedded.com and EasyIoT both caution against pushing parts beyond their rated temperature and environment, even if short‑term tests look fine. Thermal cycling over years will expose those shortcuts. When temperatures or vibration will be severe, start with industrial, automotive, or military‑grade components, even if they cost more.

Third, design software with faults in mind. Fidus’s testing work and Promwad’s embedded‑software practices converge on the same pattern: use watchdog timers, implement robust state machines, include secure remote update mechanisms, and log enough telemetry to diagnose intermittent problems. Combine these with continuous integration and hardware‑in‑the‑loop tests to catch regressions before they escape into the field.

Fourth, treat power as an integral part of the system, not an afterthought. EE Times and Arshon both show how much can be gained by profiling energy use, reducing radio duty cycles in wireless systems, and using efficient DC‑DC converters. For fanless controllers, every watt eliminated from the design translates into cooler operation and more reliability margin.

Finally, plan for traceability and lifecycle from the outset. Sealevel’s explanation of AS9100D in aerospace may sound distant from factory automation, but the underlying practices—clear bills of materials, configuration control, and vetted suppliers—prevent many painful surprises when a controller or module goes end‑of‑life in the middle of a long‑lived installation.

Brief FAQ

When is a fanless embedded controller the right choice?

It is the right choice when the controller must live in environments with significant dust, moisture, washdown, or vibration, especially where maintenance access is difficult or where ingress‑protected enclosures are mandatory. Examples include rail rolling stock, outdoor cabinets in harsh climates, mobile machinery, marine bridges, and hygienic processing zones. In cleaner, accessible indoor environments, a conventional industrial PC with managed airflow can still be a sensible option.

Can I just put an office PC in a sealed box and call it rugged?

You can put it in a box, but it will not behave like a rugged controller. Office PCs use commercial‑grade components designed for limited temperature ranges, rely on fan‑driven airflow, and lack the conformal coatings, shock‑rated mounting, and ingress‑protected I/O that Promwad, Plant Engineering, and others describe as standard for harsh environments. Once you seal such a system, heat builds up rapidly, and there is no guarantee the power supply or storage will tolerate vibration and cycling. Purpose‑built fanless controllers solve these issues by design rather than by enclosure alone.

Can fanless controllers handle modern edge workloads like analytics or vision?

Within reason, yes. SinSmart notes that modern industrial PCs based on recent Intel and ARM processors can support real‑time data acquisition, AI inference, and image processing at the edge, even in fanless designs, provided that thermal budgets are honored. The practical approach is to pair right‑sized analytics with efficient processors, offload heavy vision work where necessary, and validate workloads thermally on the actual hardware and enclosure you plan to deploy.

How do I justify the higher upfront cost to management?

Sources such as Sealevel and SinSmart frame rugged systems as lifecycle insurance. While unit prices are higher than for commercial PCs, the total cost of ownership is usually lower once you account for avoided downtime, reduced maintenance visits, fewer field failures, and longer product lifetimes. Quantifying the cost of one or two unplanned outages or site visits often makes the business case clear.

As a systems integrator, my goal is not to sell the most exotic hardware, but to deliver projects that keep running long after everyone has forgotten the commissioning date. In harsh environments, properly specified fanless embedded controllers have proven to be one of the most reliable ways to do exactly that.

References

- https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/2202538

- https://info.ornl.gov/sites/publications/files/Pub62285.pdf

- https://asi.inl.gov/content/uploads/47/2025/05/FY16_2.pdf

- https://arxiv.org/html/2506.17295v1

- https://www.automate.org/motion-control/blogs/motion-control-in-harsh-environments-engineering-for-extremes

- https://jacow.org/icalepcs2023/papers/mo2bco06.pdf

- https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1995314/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26551761_Embedded_real-time_system_for_climate_control_in_a_complex_greenhouse

- https://www.eetimes.com/Designing-systems-for-extreme-environments/

- https://www.embedded.com/design-considerations-for-harsh-environment-embedded-systems/

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment