-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

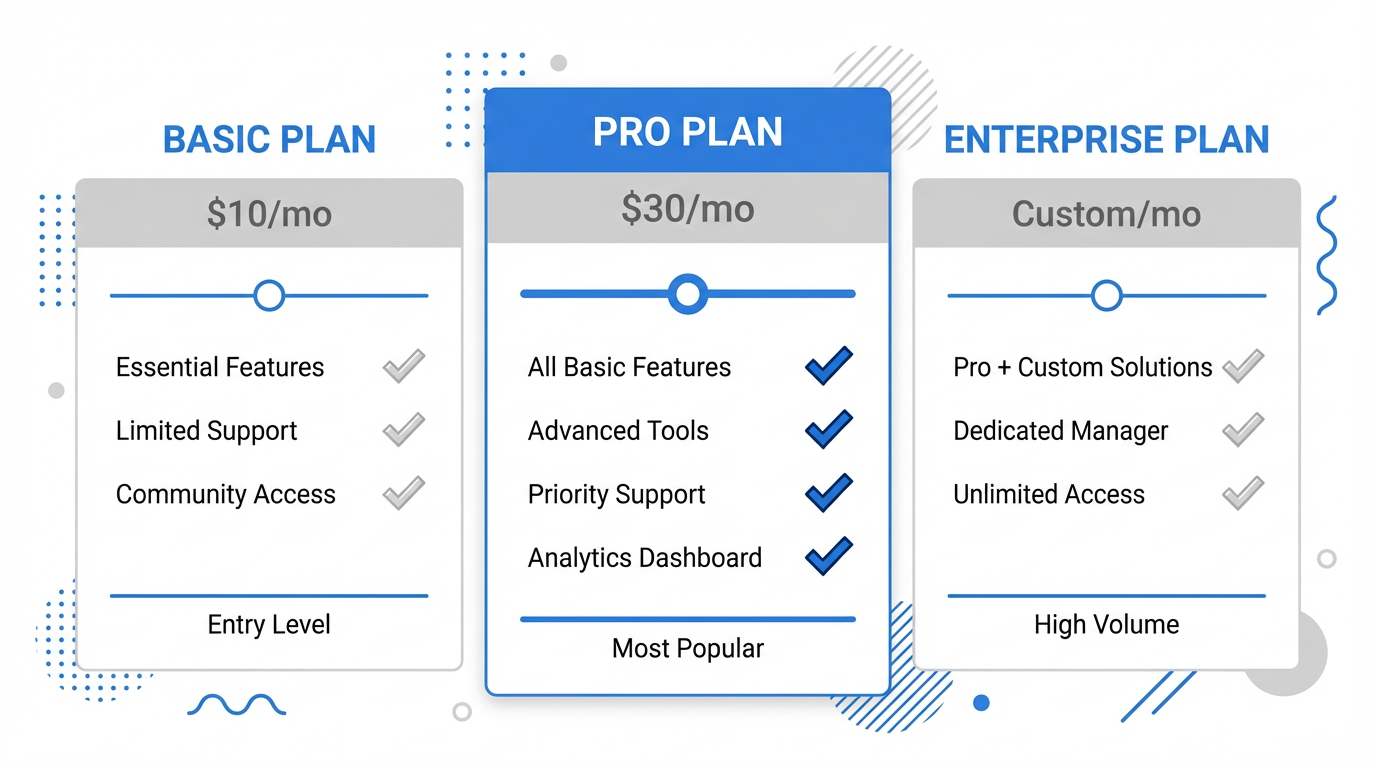

Volume Discount PLC Purchase Programs For Large Orders

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

Why PLC Volume Programs Deserve Their Own Strategy

If you buy PLCs the way many plants still do, each project is a one-off negotiation. A skid here, a packaging line there, a safety upgrade when someone finally gets budget. Every time, the engineering team rebuilds a bill of materials, purchasing calls around, and you hope the distributor “sharpens their pencil” on price.

That approach leaves a lot of money and stability on the table.

In B2B markets, one-off purchases are actually the exception. Research on bulk pricing in industrial and wholesale sectors shows that buyers typically order in larger quantities to optimize cost and secure continuity of supply. Studies on volume discount pricing in software and B2B e‑commerce, by companies such as PayPro Global and SalesLayer, reinforce the same pattern: structured volume programs increase average order value, make revenue more predictable, and strengthen long-term relationships.

The same logic applies directly to PLC hardware. When you know you will deploy the same PLC family, I/O, network modules, and accessories across a plant or an enterprise, a volume discount program is not just a price tactic; it is a strategic lever for standardization, lifecycle support, and risk control. As a systems integrator, you feel this most acutely when you are racing to commission a line and discover that the plant has six different PLC platforms because each job was bid in isolation.

The goal of this article is to treat “volume discount PLC purchase programs” as a design problem, not a haggling exercise. The research on volume pricing in other B2B categories is surprisingly transferable if you strip out the domain specifics. I will walk through how the common discount models work, where they help or hurt, and how to structure a PLC program so that it works economically for both sides and operationally for the project teams that have to live with it.

What A PLC Volume Discount Program Actually Is

At its core, a volume discount is straightforward: buy more units, pay less per unit. Investopedia defines a volume discount as a price reduction for buyers that purchase multiple units or large quantities of a good. Finance and pricing sources such as Abacum and Vendavo point out that the principle is always the same: the more you buy, the less you pay per unit, and both sides aim to benefit from economies of scale, faster inventory turnover, and better cash flow.

A PLC volume purchase program takes that basic idea and wraps it into a structured agreement that typically includes several elements at once:

You agree to concentrate a meaningful share of your PLC hardware spend on one supplier or a short list of suppliers over a defined period, usually one to three years. In return, the supplier offers lower per-unit prices or rebates as you hit specific quantity or spend thresholds. Those thresholds are usually defined on families of products: CPU platforms, remote I/O, safety modules, networking cards, power supplies, and sometimes HMIs and drives.

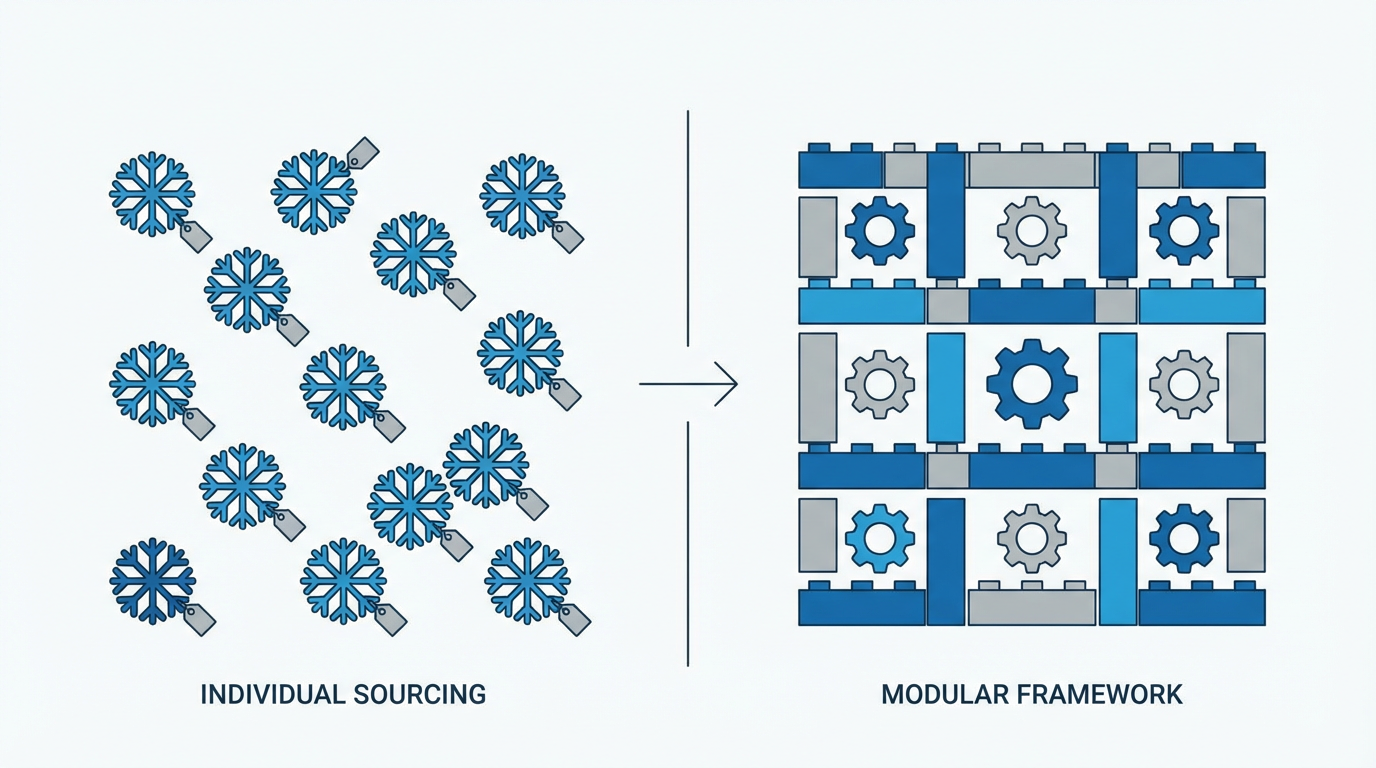

Instead of negotiating every panel as if it were a unique snowflake, you are negotiating a predictable price framework for the entire standard PLC stack you plan to deploy.

Research from Harvard Business Review emphasizes that volume discounts should not be granted just because orders are large. The only good economic reason to discount is to generate profitable volume that would not have occurred at list price, or to defend critical business where competitors already discount. In other words, a PLC volume program should drive real incremental standardization and share of wallet for the supplier, not simply reward business you would have placed anyway.

On the buyer side, a structured program should do more than produce a one-time saving on the first cabinet. It should reduce engineering friction, stabilize your parts list, simplify spares management, and improve access to technical support and replacement units over the life of the installed base.

Common Pricing Models You Will See On PLC Programs

Different industries use different labels, but most PLC volume programs can be understood in terms of the standard volume-pricing models that appear in B2B research from sources such as KvyTechnology, Qikify, Investopedia, Stripe, and Vendavo.

Tiered unit pricing

In a tiered model, different quantity bands have different unit prices, and you pay a blended rate across tiers. For example, generic tiered examples in the pricing literature describe the first block of units at one price, the next block at a lower price, and so on. Only the units inside each band receive the associated price.

Applied to PLCs, this might mean your first block of CPUs in a year are priced higher, the next block a bit lower, and a larger block lower still. This approach is common in manufacturing and B2B e‑commerce because it allows suppliers to reward larger customers while still monetizing small orders at healthier margins. Research on volume pricing platforms such as ChargeOver and Togai describes tiered structures as a way to tailor offers to different usage levels without causing extreme price cliffs.

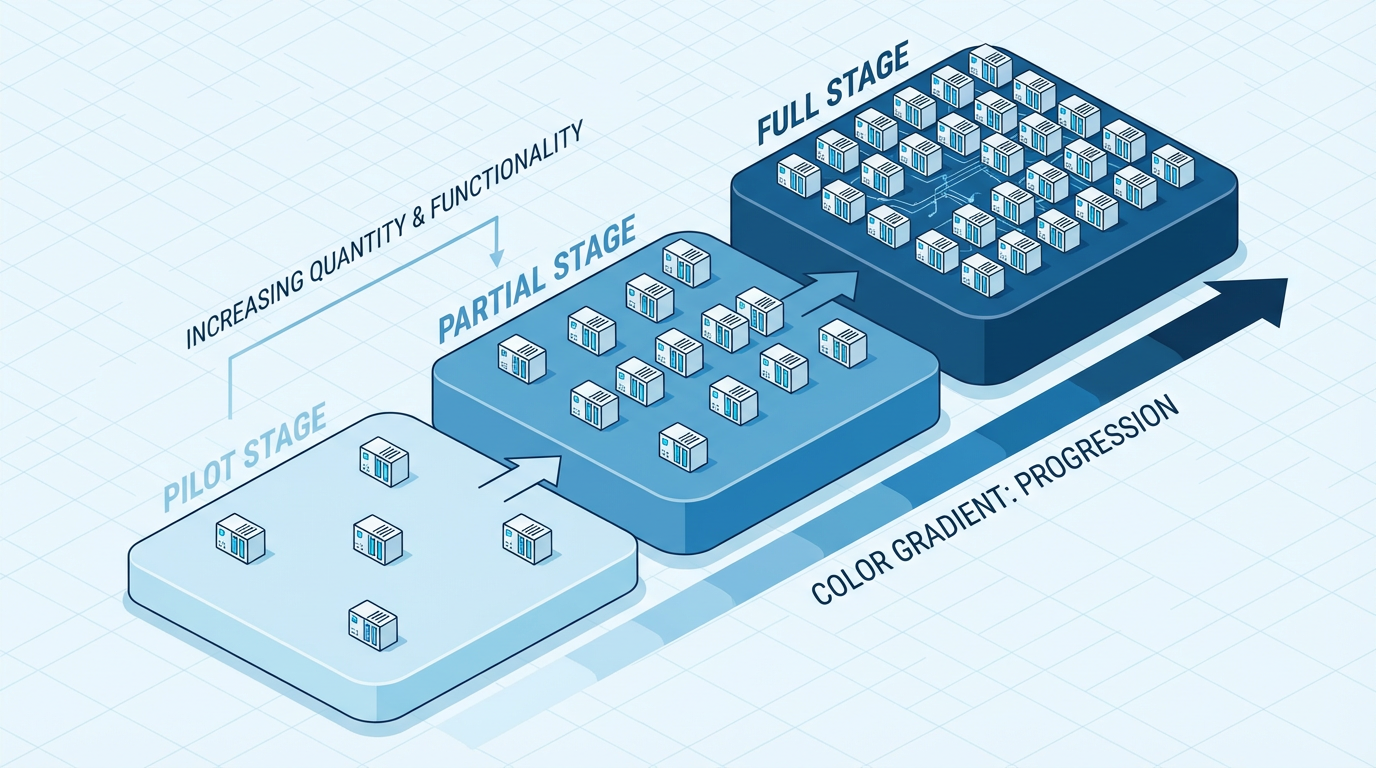

For a plant, tiered PLC pricing aligns nicely with staged rollouts: pilot lines, then partial conversions, then full-standard deployments.

Each stage carries its own economics, and you are not forced into an all-or-nothing commitment just to unlock a discount.

All-units or volume bracket discounts

An all-units or “volume bracket” model applies a single lower price to every unit once a threshold is crossed. Stripe’s analysis of volume pricing in wholesale and software uses simple examples where, once a buyer passes a quantity threshold, the reduced unit price applies to the entire order rather than just the units above the threshold.

In PLC terms, crossing the threshold of, say, a certain number of CPUs or I/O racks per year would cause the lower unit price to apply to all those items in that period. This structure is easy to communicate to non-specialists in procurement and finance and it creates a strong incentive to consolidate demand so that projects do not splinter small orders across multiple vendors.

The trade-off, as Harvard Business Review and Tremendous have both noted in their discussions of volume versus tiered pricing, is that all-units structures create steep discount cliffs. A single additional project can suddenly reprice every unit in the period, which can encourage odd purchasing behavior or strain supplier margins if the thresholds were set too low.

Cumulative volume discounts and rebates

Cumulative or retrospective discounts base the rate on total purchases over a defined horizon, not on a single order. Several sources, including Qikify, KvyTechnology, and Abacum, describe cumulative volume schemes where the buyer earns higher discounts or end-of-period rebates as their aggregated volume crosses tier thresholds.

In PLC hardware, this often takes the form of a year-end rebate on your total programmable automation spend with a vendor, paid as a credit or check.

Vendavo emphasizes that back-end rebates tied to actual shipped volume are a robust way to make sure discounts are only granted on real behavior, not on optimistic forecasts.

For project-driven environments, cumulative PLC rebates have two advantages. They smooth out the variability between project-heavy and quieter months, and they are less likely to distort individual project decisions with artificial purchasing pushes near a per-order threshold.

Contract pricing for PLC standards

Contract or agreement pricing is another common pattern highlighted in B2B bulk pricing research. Here, you negotiate fixed prices for a defined basket of items over a set period, often tied to a minimum annual spend or volume commitment. SalesLayer notes that this structure provides price stability for budgeting on the buyer side and more reliable volume forecasts for manufacturers.

For PLC environments, contract pricing underpins standardization. Once you have selected a platform and defined your standard modules, contract pricing gives engineering, maintenance, and finance a stable reference. You may still layer on cumulative rebates or tiered levels above that, but the contract establishes the baseline that project teams can design against.

Bundled and pack-based pricing

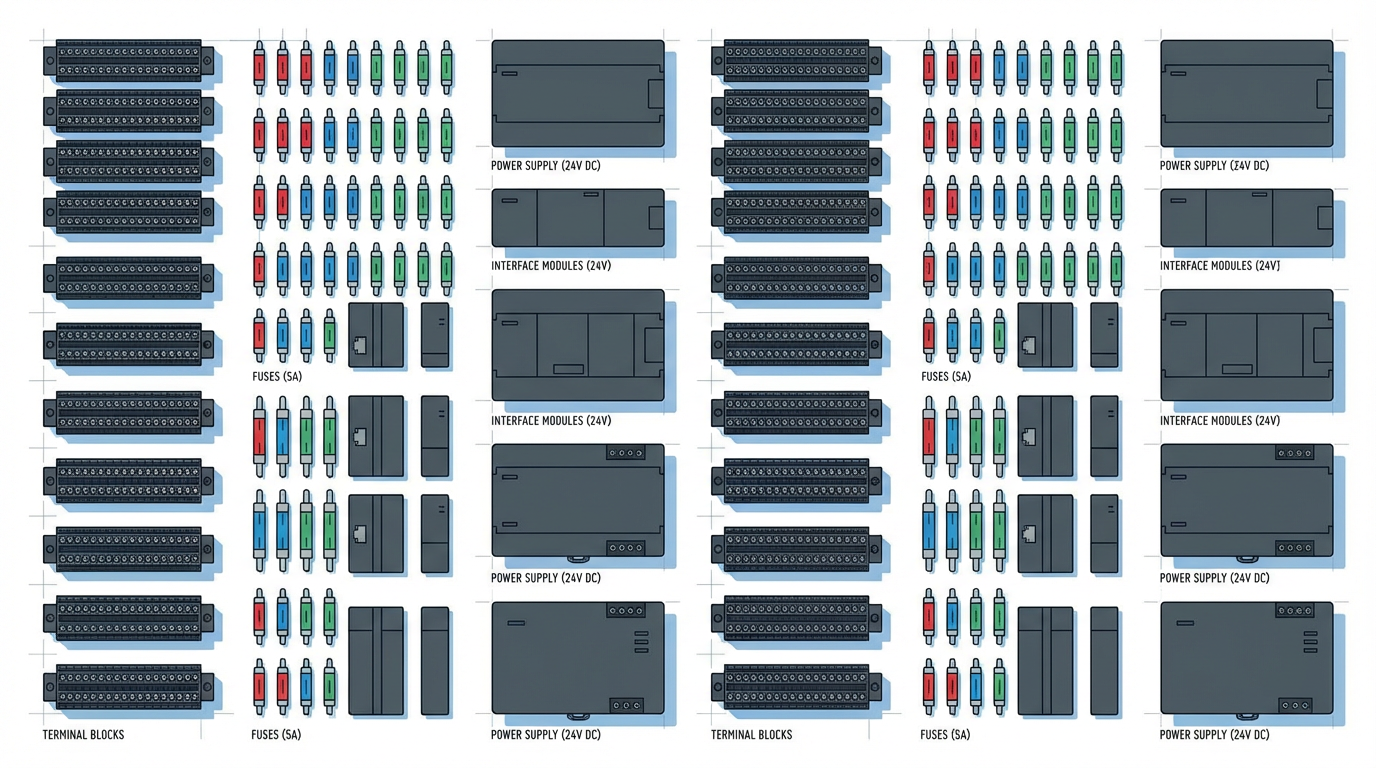

Many volume discount articles, including those from SalesLayer, Qikify, Skai Lama, and Investopedia, describe bundle pricing as a way to sell complementary products together at a lower combined price. Instead of discounting CPUs in isolation, you discount a standard panel kit, or a cell control package, or an entire line-level PLC and I/O configuration.

Bundling can make a great deal of sense with PLCs because you routinely buy modules together: CPU, power supply, rack, communication interface, a common set of digital I/O, and sometimes safety and specialty cards. A bundle discount encourages you to keep those combinations consistent and simplifies ordering and stocking.

Pack or case pricing is a related concept, common in industrial materials and office supplies: standardized multi-unit packs with predictable discounts. For PLCs, this might translate into pre-defined quantities of terminal blocks, fuses, or standard interface modules that ship together at a better unit cost.

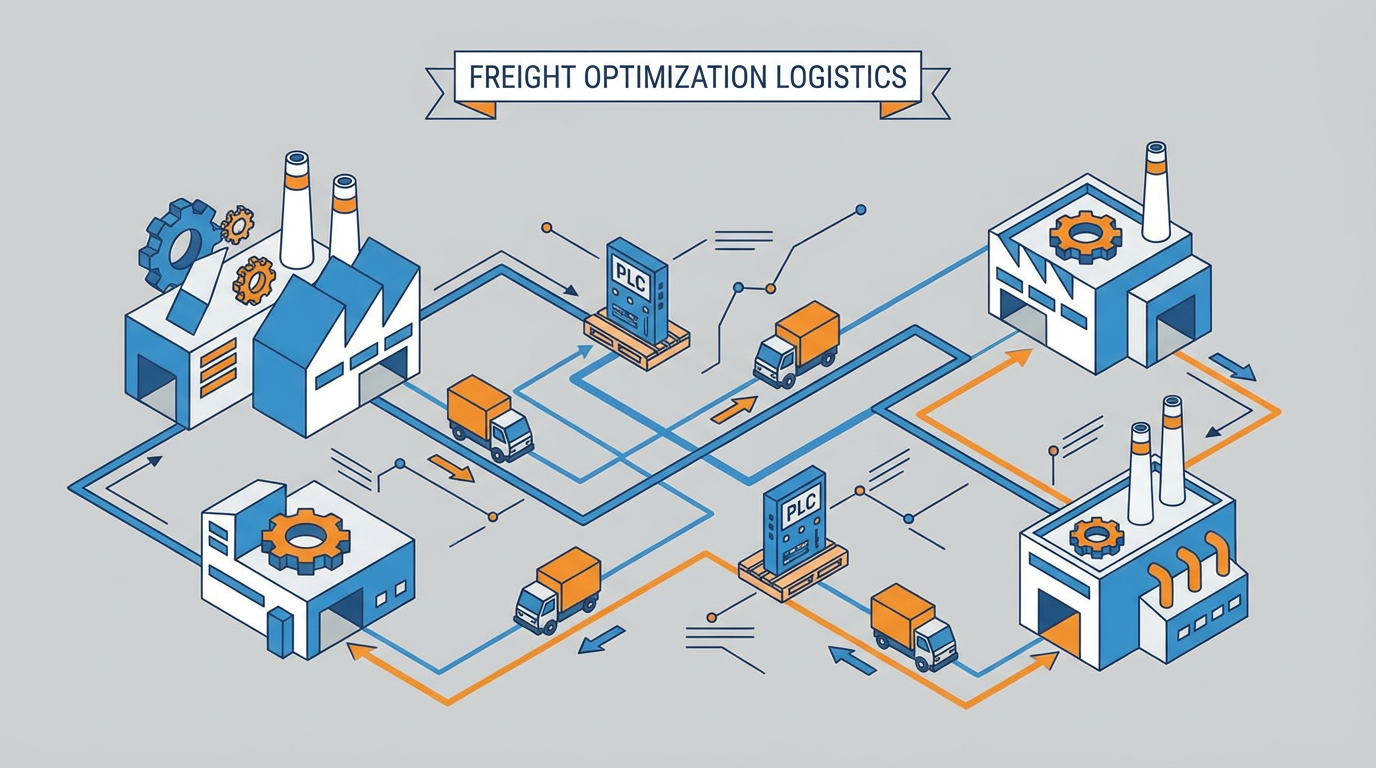

Freight and handling discounts around PLC orders

Volume discounts are not limited to the hardware list itself. Research on logistics pricing, such as the work published by Supply Chain Solutions, shows that volume-based freight agreements can reduce shipping costs by roughly 5% to more than 40% depending on volume and carrier structure. While those numbers emerge from freight, not PLCs specifically, the same concepts apply when you are shipping heavy enclosure builds or repeated hardware pallets.

PLC volume programs that include freight or handling concessions—such as reduced rates above certain order sizes or capped charges during a contract term—can remove a real barrier to centralizing orders at an enterprise level. Smaller plants frequently balk at central programs because they perceive that local sourcing saves on shipping. A well-designed volume freight agreement can counter that objection while giving the supplier more consolidated logistics.

When Volume Discounts Are Actually Worth It

Harvard Business Review has cautioned repeatedly that managers often grant volume discounts by habit, not analysis. In one example discussed in their work, a retailer cut the unit price of meat substantially for a large order, effectively handing the buyer a windfall without changing the buyer’s decision to purchase. The law of diminishing marginal utility—where each additional unit is valued less by the buyer—can justify discounts when they generate additional demand, but not when they simply give away margin on volume that was already committed.

This logic transfers to PLC hardware for both sides.

On the supplier side, the question is simple but often ignored: will a lower unit price on PLCs actually win more projects, secure more of the customer’s total PLC portfolio, or meaningfully block competitors? If the answer is no, then the “volume discount” is just a gift.

A study from Yale School of Management, focused on B2B usage-based products, offers a helpful way to think about this. The authors suggest segmenting customers into “large-need” and “small-need” groups based on intended usage, then measuring which segment is more price sensitive by looking at deal success rates. If large-need customers have lower success rates at current pricing, they may be more price sensitive and more responsive to volume discounts. If small-need customers are more price sensitive, broad PLC volume discounts could simply transfer value to big buyers who would buy anyway.

On the buyer side, the core question is whether the discount pushes you into economically rational extra volume or merely into hoarding. Research summaries from Qikify and Insight2Profit highlight that a 5% price cut can require around 38% more volume just to break even on profitability. If you accept steep volume discounts on PLCs, you need to be confident that your real project portfolio will consistently consume that extra hardware without creating dead stock, obsolescence risk, or pressure to “design in” modules solely because they are already in the storeroom.

In practice, PLC volume programs are worth pursuing when three conditions are simultaneously true. Your future demand for the chosen PLC platform is large and relatively predictable. The supplier is willing to exchange real economic value for that concentration of business. And the structure of the discount does not force you into unhealthy purchasing behavior or operational risk.

Designing A PLC Volume Program That Works In The Real World

Research on volume pricing across industries consistently recommends starting from data, not from a “15% for everybody over 100 units” rule-of-thumb. Vendors like KvyTechnology, Qikify, Vendavo, and Abacum all stress that effective volume programs are segment-specific, tested, and monitored over time.

For PLCs, the first step is understanding your own cost and demand structure. That means mapping your expected projects, typical panel designs, and standard modules over a horizon long enough to matter—often three to five years in capital-intensive industries. You want to know, by product family, how many CPUs, racks, common I/O cards, and accessories you realistically expect to purchase if you standardize.

From there, you can begin to identify products that behave like the bulk items described in Rockton and Skai Lama’s work on volume pricing: components that are typically bought in quantity and reused across many orders. Standard digital I/O cards, power supplies, terminal blocks, and panel hardware often fit this pattern. Specialty modules that you use once every few projects are poor candidates for deep volume discounts because they do not benefit from scale and are more exposed to obsolescence.

Once you have a credible demand picture, you can design tiers or thresholds that nudge behavior rather than distort it. Studies of volume pricing in retail and subscription services, such as those described by Stripe, Tremendous, and Paddle, show that thresholds work best when they sit slightly above typical consumption levels and create smooth progressions, not sudden cliffs. The same principle should guide PLC volume tiers: set breakpoints that encourage incremental consolidation, not massive one-time jumps.

Vendavo’s work on discount governance suggests a structural principle that is especially important in PLC programs: negotiate base discounts and volume-based discounts as separate levers. A base discount reflects the customer’s general willingness to pay and the competitive context. Volume discounts should explicitly reward the patterns you want to encourage: longer commitments, larger and more regular orders, and broader standardization on the supplier’s platform. When these are lumped together, the commercial team loses visibility into whether a low net price came from genuine volume behavior or from aggressive deal-making.

Researchers and practitioners also warn about complexity. Qikify, KvyTechnology, and Vendavo all describe how overly intricate discount matrices confuse buyers and sales teams, create errors in billing, and erode trust. In PLC terms, if your volume program requires an expert just to explain how many points you earn on a mixed basket of CPUs, network modules, and safety cards, it will not be used consistently. The most effective programs keep the number of tiers modest, use natural breakpoints, and express rules in plain language that project managers and purchasing analysts can understand.

Finally, any PLC volume program has to be anchored in your operational realities. Articles on shipping and logistics pricing, such as the analysis from Supply Chain Solutions, highlight the risk that volume-based agreements can strain storage and supply chains if not matched with actual capacity. If your storerooms or project sites cannot safely accommodate large forward buys of PLC hardware, then structuring the program around cumulative annual spend and frequent replenishment may be more sensible than per-order quantity triggers.

Buyer’s View: Negotiating A PLC Volume Program Without Painting Yourself Into A Corner

From the buyer side—plant owner, OEM, or integrator—entering a PLC volume program is less about demanding the deepest possible discount and more about structuring a relationship you can live with for a decade of upgrades and maintenance.

The first practical step echoes what logistics specialists advise in their work on carrier negotiations: know your numbers. For PLC hardware, that means consolidating data on your recent and planned projects, typical panel BOMs, spare parts policies, and existing installed base. Break this down by PLC family and module types so you can tell a vendor, with some confidence, what your annualized demand might look like if you standardize more aggressively.

With those numbers in hand, you can focus discounts where your demand is both large and stable. Research on volume programs in B2B e‑commerce repeatedly highlights the importance of targeting items with predictable consumption and adequate margin. For PLCs, that usually means the mainstream CPU platform and core I/O ranges that appear in almost every project, plus common accessories. This is where a concentrated relationship with a supplier will actually reduce engineering, documentation, and training complexity.

Negotiation research in shipping and B2B pricing also stresses the importance of trading flexibility as well as price. For a PLC supplier, your willingness to standardize on their platform across multiple sites, to specify their automation products in internal guidelines, or to align your preferred distributors with their channel strategy is a form of value. You can often exchange commitments of that kind for more attractive cumulative rebates, better technical support, or improved lead-time guarantees, rather than simply driving down list prices.

Economic analysis from Qikify, Insight2Profit, and Vendavo makes a final point that buyers often overlook: test the economics of the proposed tiers. If a supplier offers an additional 5% discount for crossing a higher threshold, but you would need to increase your annual unit volume by more than a third to reach that threshold, you should carefully check whether your realistic project portfolio supports that extra volume without padding every panel design or overstocking your storerooms.

Supplier’s View: Structuring PLC Programs That Protect Margin

For PLC manufacturers and distributors, volume programs are powerful but dangerous tools. The B2B pricing literature is full of examples where broad volume discounts eroded reference prices and made it difficult to raise margins later, particularly for large customers who were not actually more price sensitive.

Vendavo’s research on volume discounting and discount strategy offers a few design disciplines that are especially pertinent for PLC hardware. The first is granular segmentation: you need to understand willingness to pay by customer type, region, and product family. High-value engineered systems with long qualification cycles often sustain firmer pricing than commoditized I/O, even at larger volumes. Volume discounts should be calibrated at the segment level, not rolled out as a one-size-fits-all table.

The second discipline, echoed by Yale’s work on when to offer volume discounts, is to understand which segment is truly more price sensitive. Large PLC buyers sometimes know the market better and demand sharper pricing; in other cases they are more locked in and less sensitive than smaller, cash-constrained customers. Running the kind of deal-conversion analysis suggested by Yale’s researchers can prevent you from giving away volume discounts where they are not needed and neglecting smaller but more price-sensitive accounts where targeted incentives could grow share.

Vendavo also recommends leaning heavily on back-end rebates tied to actual shipped volume, rather than granting deep up-front concessions based solely on promised commitments. This approach aligns discounts with realized behavior, simplifies compliance, and reduces the risk that customers exceed their commitments and then demand further reductions.

Finally, suppliers should treat volume discounting as part of a broader discount governance system. Work on discount pricing strategy stresses the value of integrating volume rules with configure–price–quote tools, tracking key performance indicators such as sales volume, realized margins, and discount penetration, and providing sales teams with clear guidance on how much they can move on unit price versus which levers must be preserved for genuine volume behavior. That level of discipline is often missing when PLC programs are created as bespoke one-offs for each strategic account.

Pros And Cons Of PLC Volume Programs

A number of sources across pricing, finance, and supply chain disciplines converge on a simple observation: volume discount programs are neither inherently good nor inherently bad. Their value depends on how they are structured and managed. To make this concrete for PLC hardware, it helps to look at the upside and downside through both buyer and supplier lenses.

| Aspect | Buyer upside for PLC hardware | Supplier upside for PLC hardware | Shared risks and downsides |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unit cost and margins | Lower per-unit PLC prices, especially on high-volume modules, reduce capital spend per line. | Higher total PLC volume, better factory utilization, and potential economies of scale. | Overly deep discounts can erode supplier margins; buyers may feel compelled to overbuy. |

| Cash flow and budgeting | Contract pricing and predictable rebates improve forecasting and budget stability. | Larger, more regular orders improve cash flow timing and revenue predictability. | Large forward buys can tie up buyer working capital and stress supplier working capital. |

| Inventory and operations | Standardized PLC platforms simplify spares and maintenance; fewer emergency purchases. | More consistent demand simplifies production and inventory planning. | Inventory pressure, risk of obsolescence, and storage constraints if volumes are mis-set. |

| Customer or supplier loyalty | Buyers gain better access to support and training; clear pricing builds trust. | Suppliers lock in key accounts and increase share of wallet on PLC spend. | Expectations of permanent discounts make future price corrections difficult. |

| Competitive positioning | Lower hardware cost per machine can support more competitive bids. | Volume programs can deter competitors from displacing the PLC platform once embedded. | Aggressive discounting can provoke price wars or devalue perceived product quality. |

| Administrative complexity | One program can replace many ad-hoc negotiations and inconsistent quotes. | Clear frameworks can reduce deal-by-deal haggling and speed up approvals. | Complex tier schemes or exceptions can confuse both sides and create billing errors. |

Authors in pricing and supply chain, including Qikify, Skai Lama, Vendavo, and Vilore, repeatedly highlight that the most common failure mode is not the existence of volume discounts, but their misalignment with actual behavior. Discounts that are too generous, too complex, or too detached from real demand patterns tend to either give away margin or drive undesirable purchasing and stocking decisions.

For PLC hardware, that misalignment can be particularly painful because the lifecycle is long. A poorly designed program can lock you into a platform or a pricing structure for far longer than the contract term, simply because the installed base is expensive to change.

FAQ

Do volume discounts always make sense for PLCs?

No. Research from Harvard Business Review and Yale School of Management is very clear that discounts are justified only when they create profitable incremental volume or defend against competitive threats. If you already rely heavily on a given PLC platform and would continue to do so at current prices, deeper discounts may simply transfer value to you without changing your behavior, which is not sustainable for the supplier. Conversely, if accepting a program would require you to over-order or over-standardize on a platform that is not ideal for your applications, the apparent savings can evaporate in engineering rework and lifecycle risk.

Should I prioritize hardware discounts or lifecycle value?

Studies on volume pricing in B2B contexts emphasize that volume discounts are just one lever in a broader value equation. For PLCs, lifecycle value includes technical support, stability of the product roadmap, cybersecurity posture, toolchain maturity, and availability of skilled engineers. A modest volume discount on a platform that stays in production, receives regular firmware updates, and is well supported by integrators will usually beat a deeper discount on a platform you cannot staff or support over time. Volume programs should reinforce a sound technology choice; they should not drive it.

How do shipping and logistics discounts fit into PLC volume programs?

Work on carrier pricing and volume freight discounts shows that shipping discounts can be substantial, especially when orders are consolidated or routed through partners such as third-party logistics providers or platform-based shipping tools. For PLC hardware, including freight, handling, or rate-cap clauses inside your volume program can be as important as the unit price itself, particularly for multi-site rollouts.

However, the same cautions apply: do not commit to minimum shipment sizes or rigid delivery patterns that conflict with how your projects actually execute.

Closing Thoughts

Volume discount PLC purchase programs can be either a quiet asset or a slow-moving liability. The difference is rarely in the headline percentage. It lies in whether the program reflects real demand, uses sound pricing mechanics, and is simple enough for project teams and account managers to use without games or guesswork.

From a systems integrator’s seat, the most reliable programs are the ones that feel almost boring day to day: clear tiers, predictable pricing, rebates based on actual volume, and a shared understanding between buyer and supplier about where flexibility lives. If you approach your next PLC volume agreement with the same rigor you apply to a safety design or a network architecture, it can become one of the more durable competitive advantages in your automation portfolio.

References

- https://som.yale.edu/story/2024/you-offer-volume-discounts-crunch-numbers-heres-how

- https://upg.org/volume-discounts-boost-savings/

- https://hbr.org/2013/10/when-it-is-wise-to-offer-volume-discounts

- https://blog.payproglobal.com/5-situations-volume-discount-pricing-makes-sense

- https://blog.saleslayer.com/bulk-pricing-because-nobody-buys-just-one

- https://www.abacum.ai/glossary/volume-discounting

- https://chargeover.com/blog/volume-based-pricing

- https://www.paddle.com/blog/volume-discount-pricing

- https://www.rocktonsoftware.com/3-benefits-of-volume-pricing-and-how-to-use-it-to-your-advantage/

- https://scsolutionsinc.com/volume-discounts/

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment