-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 21500 TDXnet Transient

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

GE Fanuc 90‑70 EOL Replacement Parts: Series 90‑70 End‑of‑Life Solutions

If you are still running GE Fanuc Series 90‑70 racks, you are not alone. Many plants across the United States are operating 15‑ to 30‑year‑old GE Fanuc platforms because they are robust, the operators know them, and they have been paid for many times over. The challenge now is that the hardware is at or past end‑of‑life, spare parts prices have climbed sharply, and the people who truly know these systems are getting harder to find.

As a systems integrator who has had to keep 90‑70 systems alive while planning their eventual migration, I see the same pattern over and over. Plants wait until a critical module fails, discover that “simple” replacement parts are two to three times their original price, and then scramble to decide whether to repair, replace, or modernize. The goal of this article is to help you break that cycle and make disciplined decisions about Series 90‑70 EOL replacement parts and end‑of‑life strategies.

This is not a generic PLC overview. It is a pragmatic look at where 90‑70s usually fail, how to source and manage EOL parts, and when it makes more sense to move toward platforms such as Emerson PACSystems RX3i or modern safety PLCs. The guidance here draws on vendor and engineering recommendations from sources such as PDFsupply, Amikong, AH Group, Component Dynamics, Do Supply, Motion Control Systems, Maple Systems, and Matrikon, combined with real‑world field experience.

What “End‑of‑Life” Really Means for Series 90‑70

End‑of‑life in this context means the original manufacturer has stopped building and fully supporting the hardware. As Amikong points out, obsolescence often arrives earlier than formal EOL when parts no longer align with current technologies, materials, or standards. The practical impact on a 90‑70 user is straightforward: modules become scarce, lead times stretch, and prices increase.

Many plants have seen critical 90‑30 and 90‑70 modules selling at two to three times original list price on secondary markets. On top of that, legacy hardware no longer receives security updates and there are fewer technicians who are truly comfortable diagnosing subtle protocol and timing issues on VME‑bus‑based systems. The total lifecycle cost of “do nothing and wait for failures” is often much higher than it looks on the maintenance budget line.

Treating 90‑70 EOL as a managed, ongoing risk rather than an unpleasant surprise is the first step toward controlling that cost.

Understanding the 90‑70 Platform You Are Trying to Support

Before you can make smart decisions about replacements or migration, you need a clear picture of what you actually have. The Series 90‑70 is a modular PLC family. You build the system by combining CPU, racks, power supplies, I/O, communications, memory, and specialty modules. CPUs plug into VME‑style racks alongside I/O and communication modules. Racks are available in sizes such as five, nine, and seventeen slots, with front or rear mounting, fan trays, and dedicated rack fans for cooling, as documented by PDFsupply.

CPU tiers and capacity: what you are really paying to preserve

The CPU is the heart of the system. In a 90‑70, it determines the available memory, execution speed, I/O capacity, and redundancy options. BIN95 and PDFsupply together provide a good picture of the CPU spectrum.

Entry‑level CPUs such as the IC697CPU731 are based on a 12 MHz 80C186 processor and support up to roughly 512 discrete I/O points, with relatively small memory measured in tens of kilobytes. They lack floating‑point math and user flash memory. These units were designed for smaller, less complex machines where integer math and simple logic are enough.

Higher‑performance 90‑70 CPUs, including IC697CPX772, CPX782, CPX928, and CPX935, use 32‑bit Intel 80486DX4 processors at about 96 MHz. They can support up to around 12,288 discrete I/O points with up to 6 megabytes of user logic memory and 256 kilobytes of user flash. This class of CPU is aimed at large process units, complex machine lines, and high‑density I/O systems.

Redundant hot‑swap standby CPUs such as IC697CGR772 and IC697CGR935, along with the IC697CPM790, sit at the top of the reliability range. They also use 80486‑class processors, support between roughly 2,048 and 12,288 discrete I/O points, and are designed for high‑availability applications. The IC697CPM790 in particular, running a 64 MHz 80486DX2 with about 1 megabyte of user logic memory and separate I/O memory, is explicitly intended for Emergency Shut Down systems, fire and gas protection, and other high‑risk services.

The right way to look at these CPUs from an EOL perspective is not only by their performance but by the risk tied to them. Losing a redundant safety‑grade CPU on an old GMR‑style 90‑70 system can be far more consequential than losing a small machine‑level controller.

| CPU tier | Typical examples | I/O scale and role | EOL relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry‑level, non‑redundant | IC697CPU731 and similar | Up to about 512 discrete I/O, small memory, no floating‑point | Good candidates to run until failure, then repair or migrate |

| Mid‑range general purpose | IC697CPU771, 772, 780, 781, 782, 788, 789 | Thousands of I/O points, moderate memory and performance | Worth stocking spares; replacement or migration on repeated faults |

| High‑end and redundant/safety | IC697CPX772/782/928/935, IC697CGR772/935, CPM790 | Up to about 12,288 I/O, large memory, redundancy and safety features | Treat as high‑criticality assets; plan migration deliberately |

This table is not to sell any particular SKU, but to point out that different CPU classes justify different EOL strategies.

I/O, communications, and power modules that usually fail first

When you look through a catalog such as PDFsupply’s Series 90‑70 hardware listing, you see just how much of your system depends on aging modules. Discrete AC input modules cover 12 to 240 Vac in sixteen‑ or thirty‑two‑point densities, often grouped in isolated sets with input filters and support for proximity switches. Discrete DC input cards span about 5 to 125 Vdc at sixteen or thirty‑two points, with positive and negative logic options, TTL‑level input cards, and interrupt‑capable modules for high‑speed signals.

On the output side, there are AC output modules around 120 or 240 Vac at roughly 0.5 to 2 amps per point, DC output modules in the 5 to 48 Vdc range at similar currents, and relay output cards such as IC697MDL940 that handle high inrush loads.

Analog input and output modules handle high‑level voltage and current signals across eight or sixteen channels. Some base/expander designs support higher densities, and many use gold‑plated terminals for improved reliability over time.

Communications and bus modules range from Ethernet MMS LAN interfaces (IC697CMM741/742) to Genius I/O bus controllers and scanners, FIP bus controllers with megabytes of onboard memory, and I/O bus transmitter and receiver modules such as IC697BEM711 and IC697BEM713. There are also drive and legacy interfaces used to talk to DLAN networks and older Series Six hardware.

Finally, the system is powered by dedicated power supplies such as IC697PWR710, 711, 713, 720, 721, 722, 724, and 748. These include universal AC or DC units and DC‑only designs at voltages such as 24 or 48 Vdc, typically in the 50 to 100 watt range. Some support dual‑rack operation and redundancy. Fans and fan trays keep the racks within safe temperature ranges.

These are the parts you will be hunting for when a rack drops, an I/O loop goes dead, or an old Genius bus segment becomes unstable. Understanding this module mix is essential for prioritizing which components belong on your EOL spare‑parts list.

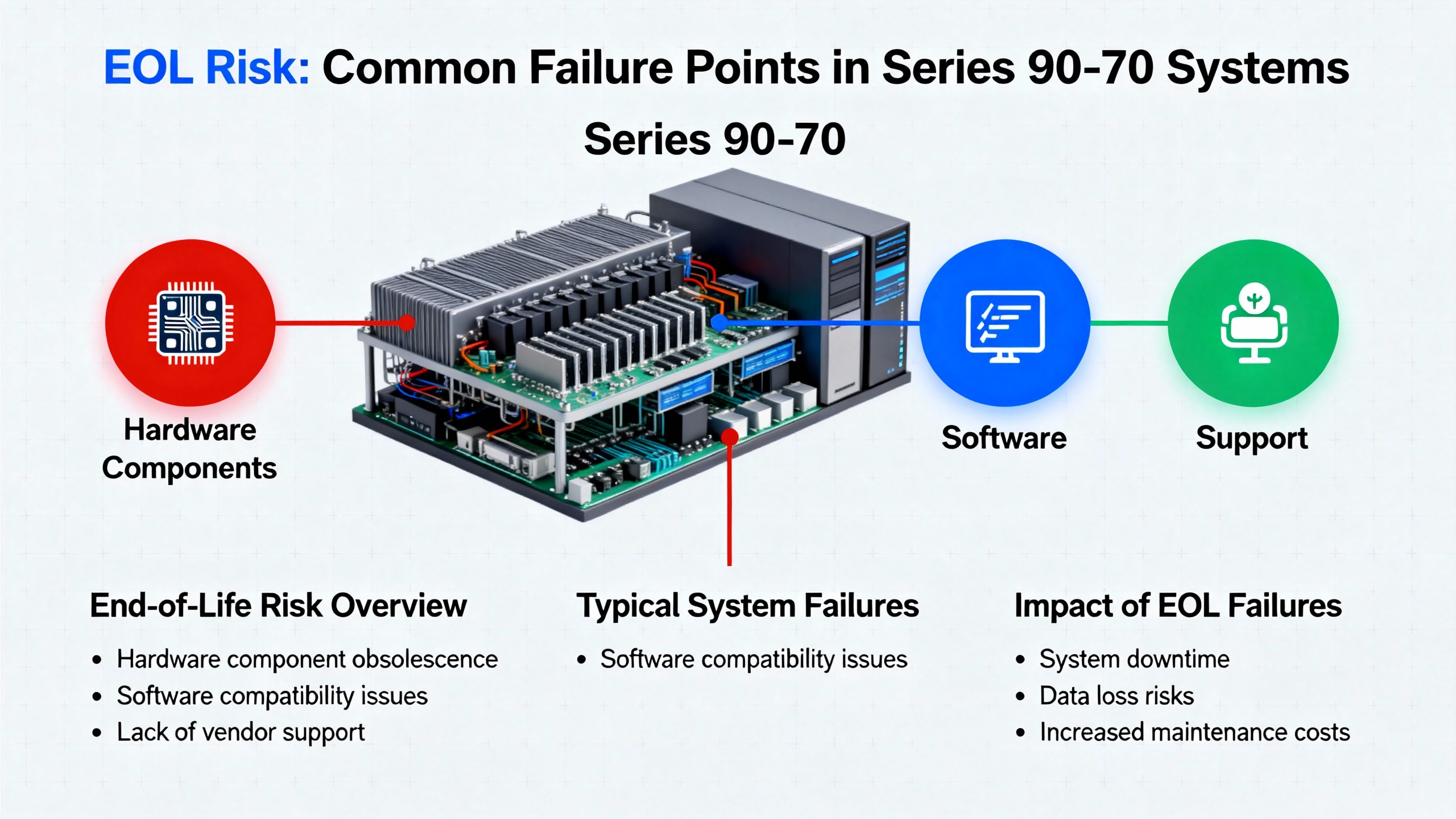

EOL Risk: Where Series 90‑70 Systems Typically Fail

The risk in an aging 90‑70 is not only that something will fail, but that it will fail at a bad time with an expensive and hard‑to‑source part.

According to analysis summarized by Amikong drawing on AH Group, Altium, Component Dynamics, and VSE, unmanaged obsolescence leads to premium broker pricing, forced redesigns on bad schedules, production delays, and higher compliance risk. For Series 90‑70 users, this translates to paying top dollar on short notice for a CPU or network module on an auction site, while the plant sits idle.

In the field, certain components tend to fail more often and more dramatically than others.

Power supplies and fans: the quiet killers

Power supplies and cooling fans are the most common sources of sudden, system‑wide failures on old 90‑70 racks. Ubestplc notes that power supplies are generally reliable, but age, voltage spikes, dust, and component fatigue catch up with them. An experienced automation engineer in that article estimates that around eighty percent of 90‑70 power supply failures trace back to blown fuses, voltage irregularities, overheating, or aging capacitors.

Power quality is critical. Dirty mains with overvoltage, undervoltage, or spikes punish supplies much more than normal loading does. The article stresses safety: fully disconnect power, wait at least ten minutes for capacitors to discharge, and use insulated tools, because a supply can retain dangerous voltages up to roughly 240 volts.

A practical troubleshooting pattern emerges in that guidance. First test the fuses, usually five‑ to ten‑amp glass or ceramic units near the input terminals, using a multimeter’s continuity function. A blown fuse must be replaced with an identical rating only. If a new fuse blows immediately, that is a strong indicator of a downstream short, often from failed surge protection components such as metal‑oxide varistors or from damaged diodes.

Next, measure input voltage at the L1, L2, and neutral terminals. Typical expected values are either 120 Vac or 230 Vac, with a healthy tolerance of about plus or minus ten percent. Fluctuations greater than around fifteen percent suggest mains problems that can stress or destroy supplies.

Then check the 24 Vdc output between the positive and common terminals under load. A healthy 90‑70 supply should deliver roughly 23.5 to 24.5 Vdc. Readings below that under at least half of normal load suggest deteriorating capacitors or other internal issues. Ubestplc emphasizes testing under load because marginal supplies often look fine with no load but sag or collapse once the system draws current.

Visual and thermal inspection is also important. Burnt smells, discolored areas on the board, bulged or leaking electrolytic capacitors, cracked solder joints, and hot spots above about 185 °F all point to internal damage.

Ubestplc suggests that many power supplies have practical service lives in the eight‑ to twelve‑year range. When voltage drift, repeat fuse failures, or visible damage show up on older units, full replacement is often more cost‑effective than repeated repair attempts.

CPUs, memory, and communications: high‑impact but less frequent

CPU failures are less common than power supply issues but more disruptive, especially on systems with redundant or safety‑related controllers. Memory expansion modules and communication cards are somewhere in between: they fail less often than power electronics but more often than CPUs.

When a Genius bus controller such as an IC697BEM734 or an Ethernet interface like IC697CMM741 goes down, entire sections of I/O can disappear. PDFsupply notes that a device like IC697BEM734 coordinates token‑passing communication for up to thirty drops per channel, with built‑in diagnostics and global data capabilities. If that module fails outright, you do not just lose one input or output; you can lose a large part of a process unit.

Similarly, when a CPU with redundancy or safety logic fails and you have no spare, you may face an unplanned migration to a new platform under maximum pressure.

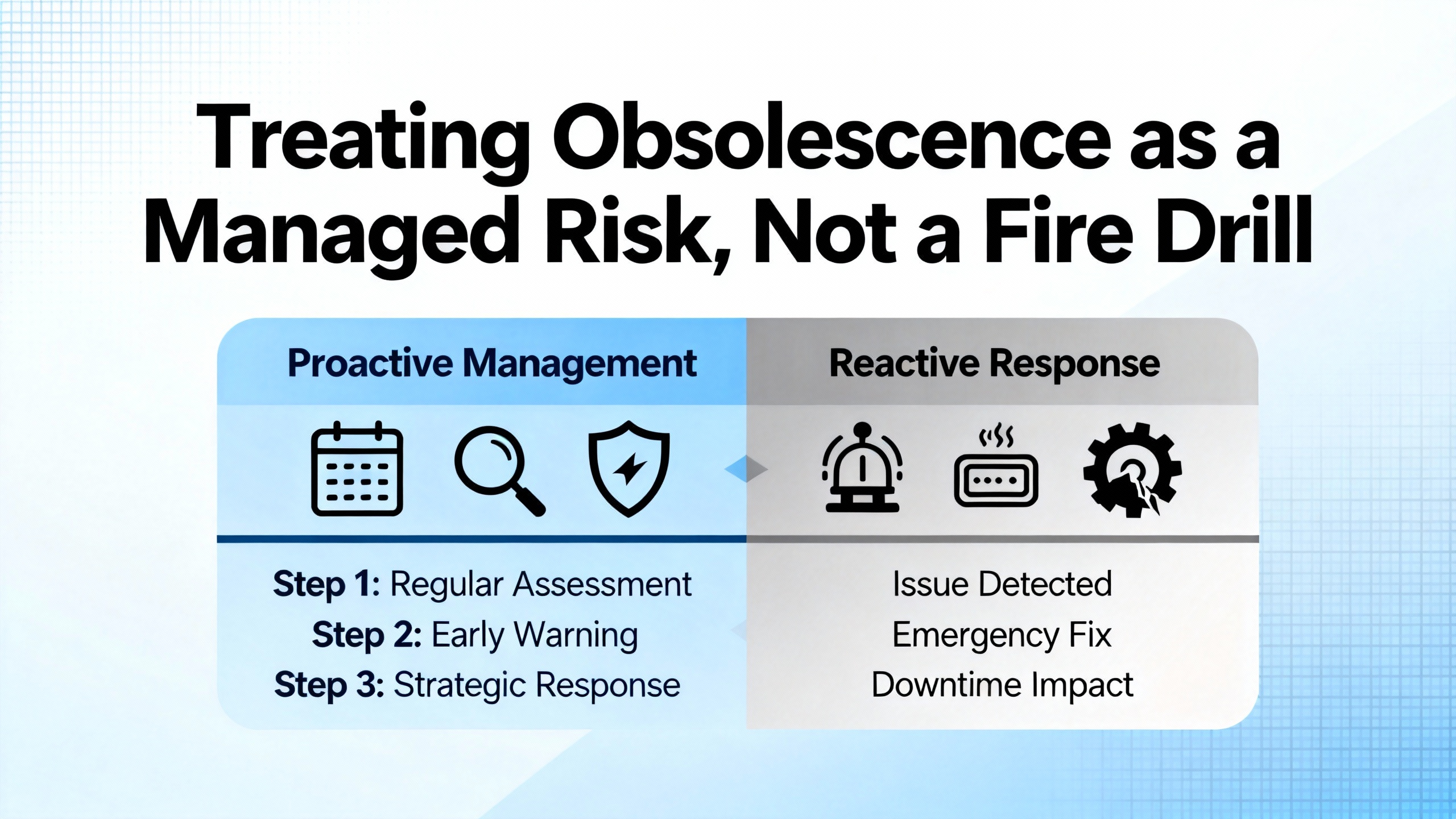

Treating Obsolescence as a Managed Risk, Not a Fire Drill

Amikong’s review of EOL strategies for GE Fanuc hardware aligns well with what works in practice. The best‑run plants treat obsolescence as a formal, ongoing risk. They track lifecycle status in bills of material and lifecycle management tools. They assign an obsolescence owner, often in reliability engineering or controls, who has clear responsibility for monitoring vendor notices, forecasting lifecycles, planning last‑time buys, and validating third‑party distributors to avoid counterfeit or marginal components.

This mindset applies directly to the 90‑70. The hardware is mature and stable, but also aging and finite. Without an owner, EOL becomes “somebody else’s problem” until it causes a shutdown.

Run, repair, or replace: deciding what to do with each asset

A run‑repair‑replace framework, outlined by Amikong, is particularly useful for 90‑70 systems.

Running makes sense where mean time between failures is still acceptable and spares are predictable. A non‑critical discrete I/O card that has not caused trouble in years, with several tested spares on the shelf, is a good candidate to keep running with minimal intervention.

Repair or service exchange is often best for assets that are important but not safety‑critical. Warranty‑backed repairs or refurbished modules with proper testing let you squeeze more value out of existing hardware without committing to a major migration. For example, a Genius bus controller or Ethernet module in a non‑critical area can often be sent out for repair while a spare takes over.

Replacement or migration is appropriate when failures are recurrent, when an asset is mission‑critical or safety‑critical, or when repair costs approach the cost of moving to a newer platform. A redundant 90‑70 CPU handling emergency shutdown, fire and gas, or high‑consequence interlocks belongs in this category once parts and expertise become scarce.

You can combine these choices on a single system. You might keep legacy discrete I/O modules running under a modernized CPU and communications layer while planning a longer‑term migration of the entire rack.

| Asset condition | Series 90‑70 example | Recommended approach |

|---|---|---|

| Stable, low criticality, spares in hand | Small 90‑70 CPU or low‑density I/O card in a utility | Keep running and monitor; replace on failure |

| Moderate failures, non‑safety critical | Genius bus controller feeding non‑critical packaging | Use repair or service exchange; stock at least one spare |

| Frequent faults or safety/mission critical | Redundant CPU for ESD or fire and gas interlocks | Plan and execute migration to a modern safety PLC or RX3i |

This type of classification provides a rational basis for where to spend limited capital on EOL replacements or migrations.

Building a realistic spare‑parts strategy for 90‑70

A disciplined spare‑parts strategy, as described in the Amikong article, starts with a focused audit. Rather than trying to catalog every card in every panel, begin with five to ten high‑risk components across the plant. For a 90‑70, that typically includes CPUs, power supplies, high‑density I/O, network modules such as Genius or Ethernet cards, and legacy HMIs.

For each, identify the installed quantity, operating environment, typical failure modes, and current sourcing options. Stage tested spares where they are actually needed, in climate‑controlled storage with clear labels and logs. Make sure program backups exist not only for the PLC CPU, but also for any associated network configuration, communication gateways, and HMIs.

It is also crucial to verify that backups include comments, I/O maps, and descriptions wherever possible. Several user discussions about GE programming tools highlight that early tools such as Logicmaster and VersaPro handle comments and variable descriptions differently than newer software. Once comments are lost, recovering the design intent becomes much harder during a crisis.

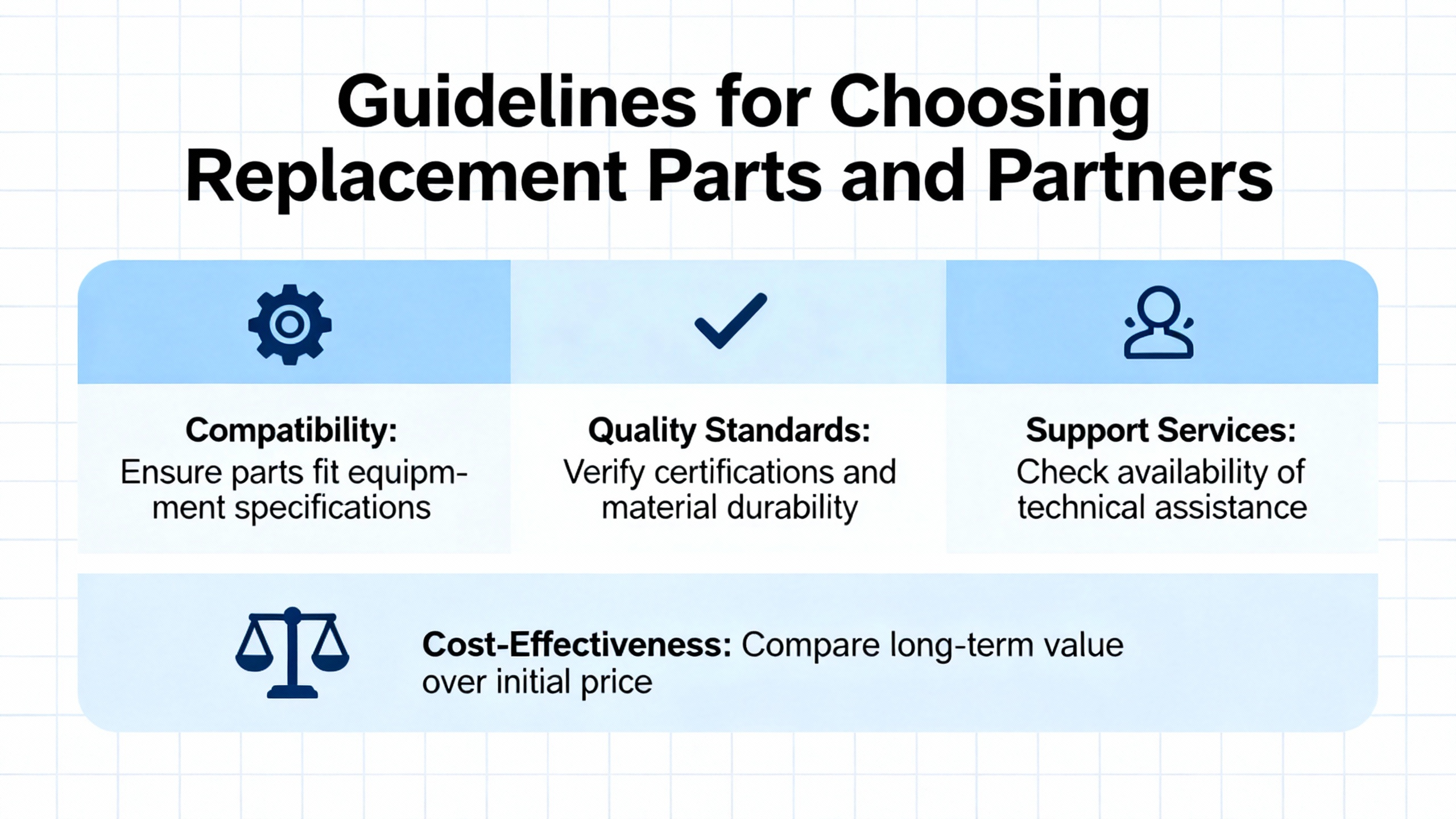

Choosing Replacement Parts and Partners

When a Series 90‑70 module finally fails, you will likely be choosing between OEM‑new, new‑old‑stock, refurbished, and third‑party equivalent parts. Amikong and other sources provide helpful guardrails for that choice.

OEM‑new or new‑old‑stock is the gold standard for high‑criticality assets: main CPUs, safety‑related control, and primary power supplies. These parts, when available, offer the closest match to original performance and reliability. The downside is cost and availability. On critical items, that premium is often justified.

Refurbished or tested used parts fill an important middle ground for balance between cost and speed. Vendors such as PDFsupply specialize in supplying tested, warrantied Series 90‑70 hardware across CPUs, I/O, communication cards, and power supplies. For non‑safety‑critical applications, a refurbished power supply or I/O card from a reputable supplier can be entirely reasonable.

Third‑party equivalent modules should be used carefully. For non‑safety‑critical applications, they may offer attractive savings, but you need to verify electrical specifications, environmental ratings, and certifications. For anything with safety implications, OEM or high‑quality refurbished parts are typically the safer choice.

Validating distributors and brokers is not administrative overhead; it is a risk‑control step. AH Group, Component Dynamics, and VSE all emphasize the need to vet suppliers to avoid counterfeits or poorly repaired units.

When to Modernize Instead of Replacing Like‑for‑Like

At some point, chasing individual replacement parts becomes less sensible than planning a controlled modernization. Modern platforms offer more processing headroom, better redundancy, ongoing security patching, richer diagnostics, and much stronger integration with information systems. Do Supply highlights that the total cost of ownership for modern platforms can be lower than staying with aging GE Fanuc hardware, even when upfront costs are higher.

Several practical modernization paths exist for 90‑70 users.

Migrating 90‑30 and 90‑70 to PACSystems RX3i

Motion Control Systems describes a modernization path from Series 90‑30 and 90‑70 to Emerson PACSystems RX3i that focuses on preserving engineering work rather than ripping everything out. The strategy is to migrate the controller to RX3i while reusing existing Series 90 I/O cards where possible and only replacing them as necessary. Control software can be converted using PAC Machine Edition, translating ladder logic and configuration from the 90‑series platform into RX3i.

PACSystems RX3i acts as an industrial edge controller. It sits close to the machine, handles real‑time control, and also contextualizes data at the machine level for better analytics. PDFsupply’s review of GE protocols notes that RX3i supports modern Ethernet‑based protocols such as SRTP, Modbus TCP/IP, OPC‑UA, and Profinet, as well as legacy serial protocols like Modbus RTU and ASCII. This makes RX3i a natural bridge between old and new.

For a 90‑70 user, this means you can plan a phase where you keep your existing I/O racks and many of your field terminations but move the CPU and network interfaces forward to an RX3i platform.

Safety and SIL migrations from 90‑70 GMR

Amikong notes that 90‑70 and 90/70 GMR safety systems are typically migrated to modern SIL2 or higher safety PLCs using automated extraction and validation tools. The core idea is to extract logic and I/O maps, translate them into the target safety platform, validate them rigorously, and stage cutovers carefully.

This is especially important for systems using safety‑oriented CPU models such as IC697CPM790, which was designed specifically for emergency shutdown and fire and gas applications. For these applications, patching in another obsolete CPU rarely makes sense; a planned migration is almost always the better long‑term investment.

HMI upgrades as a fast win

Legacy HMIs tied to GE Intelligent Platforms or Fanuc CNCs are often a weaker link than the PLC hardware itself. Maple Systems positions its HMI hardware and software as a drop‑in replacement for existing GE Intelligent Platforms PLCs, Fanuc PLCs, and Emerson Machine Automation Solutions. According to Maple Systems, their HMIs support RX3i protocols and a wide range of Fanuc CNC controllers, including 0i, 30i, 31i, 32i, and 35i series, along with more than three hundred other PLC and controller types.

The vendor emphasizes easy implementation and notes that they do not require service agreements, which can reduce ongoing licensing costs. Professional support is part of the offering. For many plants, upgrading HMIs to modern, well‑supported hardware while leaving proven 90‑70 control logic in place is a relatively quick win for usability and visibility.

SCADA and historian connectivity with legacy 90‑70

Even if you keep a 90‑70 in place, you can modernize the way you connect to it. Matrikon’s OPC server for GE Fanuc PLCs provides high‑speed, secure read and write access between Series 90‑70 controllers and OPC‑enabled applications such as historians and HMIs. It supports SRTP over Ethernet and SNP or SNPX over serial lines, allowing it to communicate with popular GE families including 90‑30 and 90‑70.

Key features of the Matrikon server include tag‑level security, fail‑over capability with primary and standby connections, device‑level redundancy, and automatic tag generation to reduce engineering effort. This type of connectivity layer lets you maintain an old 90‑70 while integrating it with modern SCADA, analytics, and reporting tools.

On the SCADA side, platforms such as Ignition do not have native drivers for GE Fanuc 90‑70 or 90‑30 protocols, as noted in an Ignition community discussion, but they work well with data once it is exposed through a driver such as Kepware. The recommended architecture is to use Kepware as the protocol layer for the 90‑70, then point Ignition to Kepware for tags, alarms, trends, and visualization.

Software and Support Considerations

Hardware is not the only EOL problem. Software and operating systems are also aging.

A community discussion on replacement software for GE Fanuc 90‑30 controllers outlines the landscape clearly. Older GE controllers were originally programmed with Logicmaster or VersaPro. Modern support has consolidated under Proficy Machine Edition, now maintained by Emerson after GE transferred the product line. Proficy Machine Edition can connect to a PLC regardless of which of those earlier tools created the original program, but there are compatibility nuances between project formats.

Logicmaster and VersaPro are not interchangeable. Logicmaster cannot work with projects created in VersaPro, and VersaPro does not run on operating systems newer than Windows XP. Logicmaster can run under newer Windows versions using DOSBox, but serial communications are often unreliable in that setup. For reliable serial communication to a legacy 90‑30 or 90‑70, the article’s contributors recommend using a Windows XP physical machine or virtual machine.

Programming connections often use a fifteen‑pin RS‑485 port on the power supply, with typical defaults around 19200 baud, one stop bit, and odd parity. Logicmaster only supports COM1 through COM4, so USB serial adapters must be configured carefully to map into the supported range. Community experts caution that many connectivity issues blamed on cables actually originate in the timing and protocol limitations of the older software.

Several engineers in those discussions recommend contacting local Emerson distributors, including long‑time distributors such as GEXPro and Powermation, both for technical support and for obtaining or temporarily licensing Proficy Machine Edition. They also stress avoiding pirated software and relying instead on official downloads or trusted contacts for legacy tools like Logicmaster.

Another forum thread on Control.com highlights that GE 90‑30 and 90‑70 hardware is generally respected, but the software family is criticized for weaker forward and backward compatibility compared with some competitors. By contrast, many Allen‑Bradley tools can go online with older PLC‑5 controllers regardless of which package originally configured them. This difference matters when you are trying to maintain old GE hardware from modern engineering laptops.

All of this reinforces a basic point. As you plan EOL hardware strategies, you should also plan your software strategy: which engineering stations you will keep or virtualize, which programming packages you standardize on, and how you will preserve knowledge about communication settings and project structures.

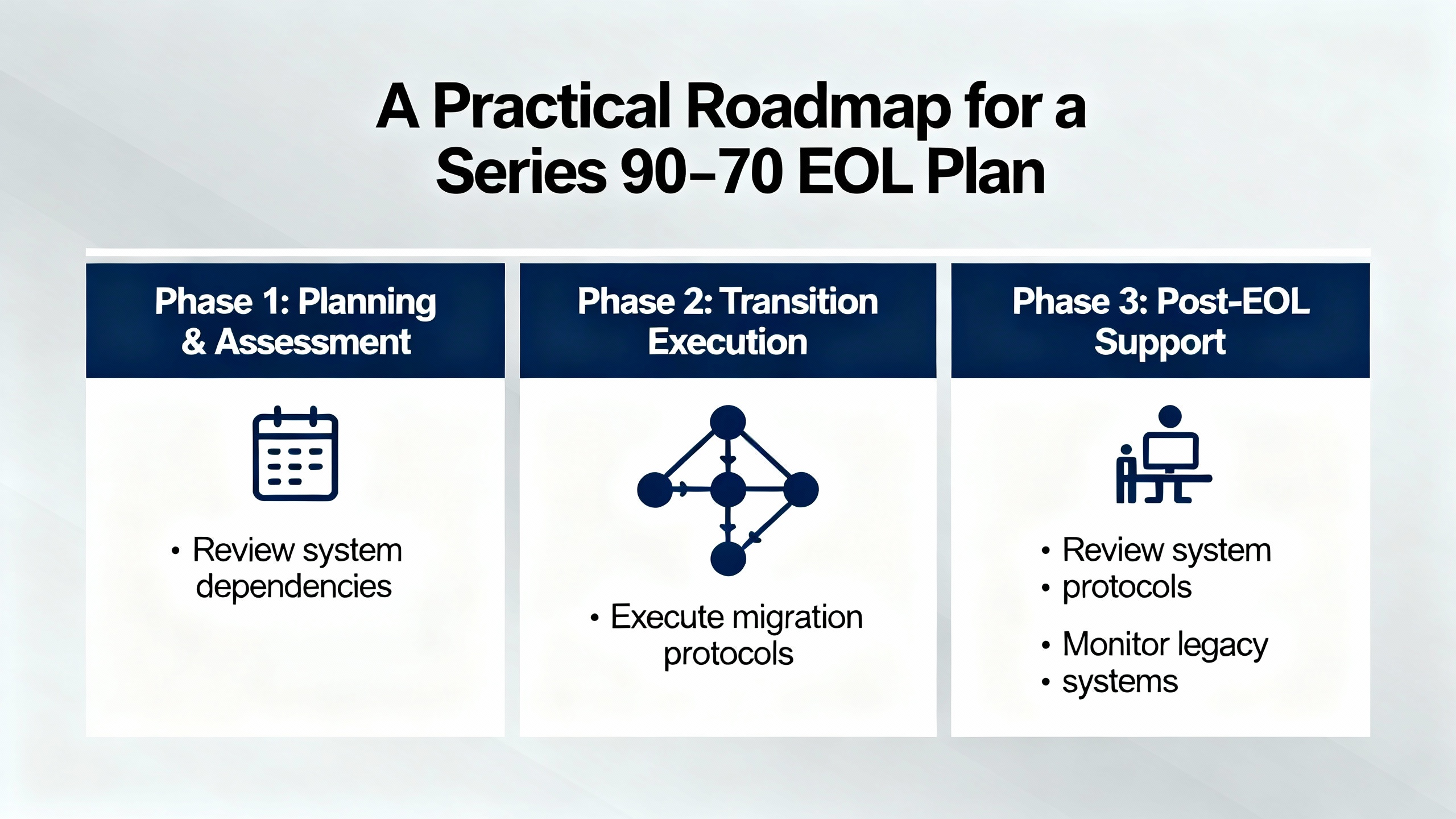

A Practical Roadmap for a Series 90‑70 EOL Plan

Every plant is different, but most effective 90‑70 strategies follow a similar pattern, echoed by migration methods from firms such as CIMTEC and Cybertech and summarized in the Amikong article.

First, inventory your installed base. That means not only rack and module part numbers, but also firmware where practical, communication protocols, and connected devices such as HMIs and drives. Document all serial and fieldbus protocols being used, including SNP, SNPX, SRTP, Genius bus, Profibus‑DP, and any gateways.

Second, identify high‑risk and high‑criticality components: redundant CPUs, safety‑related controllers like IC697CPM790, power supplies, network modules, and any module with a long replacement lead time or high price premium. These become the focus for targeted spares, repair contracts, or early migration.

Third, stabilize the existing system. That includes replacing or repairing suspect power supplies and fans, cleaning racks and cabinets, verifying grounding and shielding on communication networks, and ensuring up‑to‑date backups of programs and HMI applications. Ubestplc’s step‑by‑step fuse and voltage check approach is a good template for validating power quality across racks.

Fourth, decide where you will run, where you will repair, and where you will replace or migrate, applying the run‑repair‑replace framework. Safety systems and mission‑critical assets often move quickly into the migration column, while less critical I/O and non‑essential subsystems continue running with minimal changes.

Fifth, design and bench‑test your migration. For an RX3i modernization, that means converting logic in PAC Machine Edition, bench‑testing with simulated I/O and connected HMIs or drives, and validating communication paths using protocols such as Modbus TCP/IP or SRTP. For safety migrations, it means using extraction and validation tools and following safety lifecycle practices.

Finally, execute migrations in low‑risk windows with clear rollback plans. That includes keeping old hardware available as a fallback until new systems have run successfully under real load, and capturing updated documentation and as‑built details so future work is easier.

FAQ

Is it safe to keep running a Series 90‑70 that is more than twenty‑five years old?

Many plants do exactly that, and the hardware itself was built to be robust. The real question is not age alone but whether you understand the risks and have a plan. If you have audited your high‑risk components, staged tested spares, stabilized power and cooling, and validated backups, then running a 90‑70 can be an acceptable interim strategy. If on the other hand you have no spares, no backups, and no clear path forward, you are operating with unnecessary risk.

Are refurbished 90‑70 parts a good idea?

Refurbished parts from reputable vendors that fully test and warrant their modules, such as those described by PDFsupply and Amikong, can be an excellent choice for non‑safety‑critical applications. They provide a balance between cost and availability. For safety‑related systems and the most critical CPUs, OEM‑new or new‑old‑stock is still preferable when available.

Do I need to replace my 90‑70 to modernize my SCADA system?

Not necessarily. Connectivity layers such as Matrikon’s OPC server for GE Fanuc allow you to bridge between 90‑70 controllers and modern OPC‑enabled SCADA and historian systems using Ethernet protocols like SRTP, as well as serial protocols such as SNP and SNPX. In addition, SCADA platforms such as Ignition can connect to 90‑series PLCs via Kepware drivers. This lets you upgrade visualization, alarming, and analytics without immediately replacing the controller hardware.

Closing

If you treat your GE Fanuc Series 90‑70 as a “black box that just runs,” end‑of‑life will eventually show up as a crisis. If you treat it as a critical but aging asset with a defined lifecycle, it becomes a manageable engineering problem. Map your installed base, stabilize the essentials, commit to a realistic run‑repair‑replace strategy, and choose your modernization path deliberately. Done that way, your 90‑70 will keep earning its keep today while you prepare the plant for the next twenty years of control technology.

References

- https://www.plctalk.net/forums/threads/newbie-converting-from-90-70-to-rx3i.104142/

- https://www.alibaba.com/showroom/ge-fanuc-plc-programming-cable.html

- https://bin95.com/plc-configuration/ge-fanuc-series-90-70-cpus.htm

- https://www.ebay.com/itm/112297360945

- https://maplesystems.com/ge-fanuc-hmi-alternative/?srsltid=AfmBOoobNM_kh-JcMS6TzjNaBzwxwKFnC3yuLasO-E-6ax-tEfaa94to

- https://community.oxmaint.com/discussion-forum/best-replacement-software-for-programming-ge-fanuc-90-30-controllers-on-windows

- https://www.amikong.com/Blog/n/ge-fanuc-end-of-life-parts

- https://www.motioncontrolsystems.co.za/blogs/news/modernization-ge-fanuc-90-30-and-ge-fanuc-90-70-plc-controllers

- https://www.eng-tips.com/threads/ge-90-70-io-conversion.344457/

- https://forum.inductiveautomation.com/t/connecting-ignition-to-an-existing-ge-fanuc-90-70-or-90-30-plc/67531

Keep your system in play!

Top Media Coverage

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shiping method Return Policy Warranty Policy payment terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2024 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.