-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

HMI Communication Port Failure Repair: Connection Solutions

When a line operator tells me, “The HMI is fine, it just will not talk to the PLC,” I know we are in dangerous territory. A dead or intermittent communication port turns a million‑dollar line into a very expensive sculpture. The good news is that, in most plants, these failures are diagnosable and fixable with a clear method rather than guesswork and random cable swapping.

Drawing on years of systems integration work and backed by references from sources such as Control.com, Siemens documentation, Flextech Industrial, AutomationDirect training materials, and multiple repair specialists, this article lays out a pragmatic way to diagnose and repair HMI communication port failures, and to design your systems so they fail less often.

Why HMI Communication Ports Fail In The Real World

On the plant floor, HMI communication problems rarely come from a single cause. Research and field reports consistently point to a handful of recurring themes. Hardware problems such as loose or damaged cables, worn connectors, and failing ports show up again and again in guides from Flextech Industrial, Xinje, and Kinseal. Network issues like IP conflicts and duplicate addresses are highlighted in a Control.com technical article on HMI troubleshooting and in Siemens communication diagnostics materials. Software and configuration errors are another large bucket, from mismatched baud rates on serial links to incorrect protocol settings or outdated firmware, as described by Flextech Industrial and Xinje.

There is also a “logical layer” above the wire where communication objects and drivers can fail even though the hardware looks perfect. AVEVA documentation, for example, maps specific communication break conditions such as a “break between PLC and DIObject” or “node disconnected” to status codes, indicating that the software’s view of a port can be broken even while the port hardware is intact. Siemens materials on WinCC and SIMATIC CPUs show similar behavior: the PLC is reachable from engineering tools while the HMI channel repeatedly connects and disconnects because of runtime‑level issues.

Environmental and power conditions sit behind many so‑called “mystery” failures. Articles from Kinseal and Xinje emphasize that heat, dust, vibration, electrical noise, and unstable power can degrade ports and connectors over time. Power fluctuations and grounding issues are also cited in several troubleshooting guides as triggers for intermittent communication, even when other hardware appears fine.

Security and encryption are a newer, but very real, source of trouble. A TIA Portal note explains that from version 17 onward, HMI–PLC communication is encrypted by default. If certificates are missing or mismatched, the HMI may fail to connect or drop off, which on the plant floor looks exactly like a port failure until someone checks the security configuration.

In other words, “port failure” is often the visible symptom of a deeper stack problem. Repairing it reliably means separating the layers and proving where the fault really is.

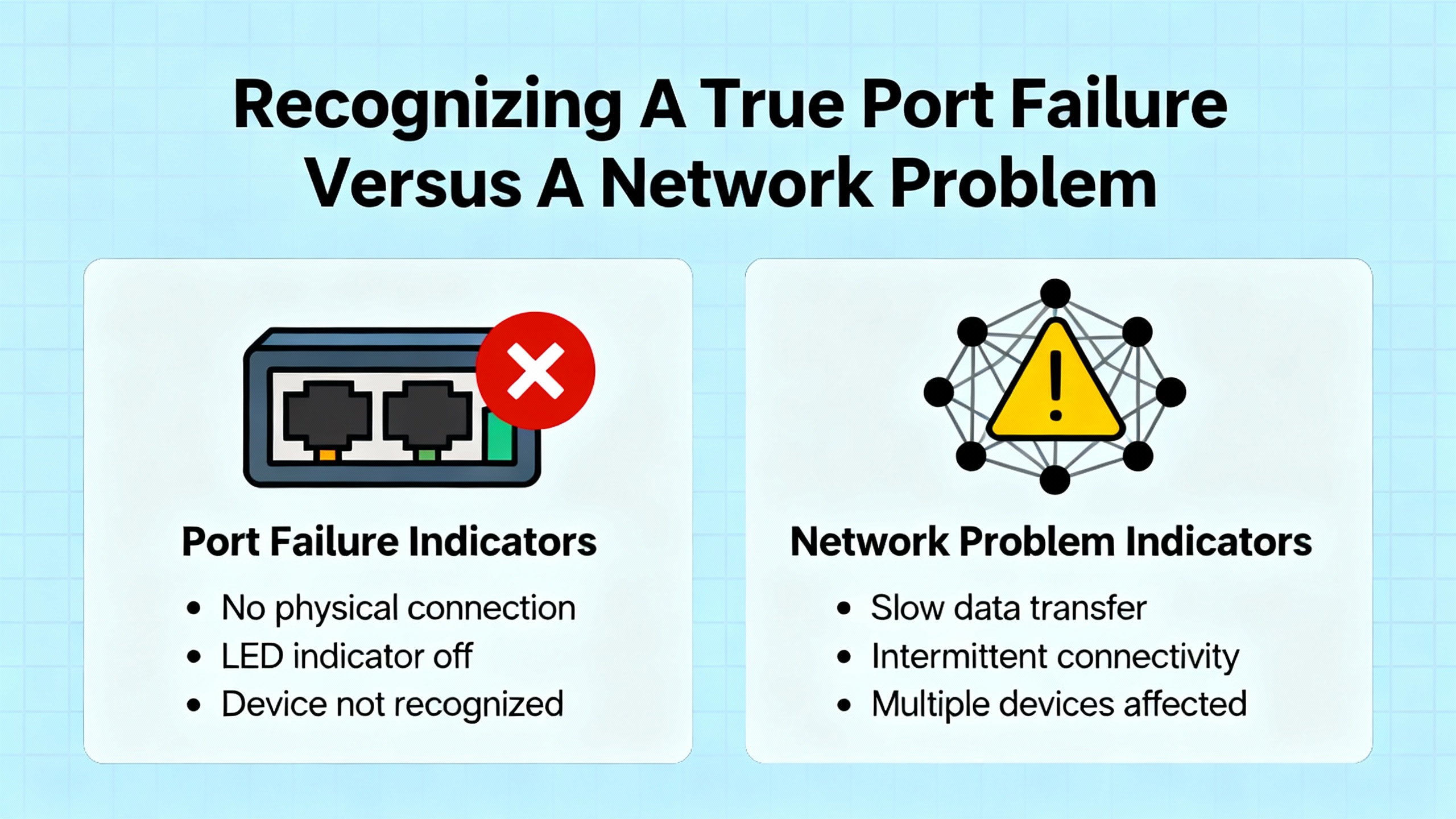

Recognizing A True Port Failure Versus A Network Problem

A key skill for a seasoned integrator is telling the difference between a genuinely bad port and something upstream. If you misdiagnose this, you can waste days replacing panels and PLCs while the real trouble is a misconfigured protocol or a firewall rule.

User reports and case studies offer some useful patterns. An AutomationDirect community discussion about DL06 PLCs and EZ‑Automation panels describes “PLC COMMUNICATION TIMEOUT” messages that appear across half a dozen HMIs and PLCs. The HMIs are on short RS‑232 links, running at 38,400 baud. Timeouts are frequent and growing, and the engineer suspects HMI logic issues but has no conclusive evidence of hardware failure. The breadth of the issue suggests a systemic configuration or design problem rather than a single bad port.

In a different case from an Omron CP1E PLC and NB‑series HMI, the HMI shows “PLC No Response 00‑00‑1.” The HMI transmits a pulse every couple of seconds; the PLC’s RS‑232 LED flashes, but the PLC never replies. An internal diagnostic word in the PLC sets a bit indicating an error at the built‑in RS‑232 port, and clearing the bit has no effect. The same HMI behaves the same way on two different PLC ports. This pattern points more strongly to a PLC‑side serial configuration or port issue than to the HMI port.

On the Ethernet side, a Siemens WinCC 6.0 user reports that an S7‑300 CPU connects to the HMI for a few seconds and then drops repeatedly, even though the engineering tool on the same PC communicates with the PLC without problems. This is a classic sign that the network hardware is fine but the HMI channel configuration is wrong or some runtime component is misbehaving.

A Control.com article on HMI troubleshooting makes another important distinction. Intermittent ping responses between an HMI and PLC often indicate loose terminations or marginal connections, especially at RJ45 connectors, whereas complete lack of ping response may indicate a major wiring failure, such as a damaged cable or a prior voltage spike.

Pulling this together, operators and engineers should treat port problems as layered events. If multiple tools can talk to the PLC but the HMI cannot, suspect the HMI’s configuration, driver, or security before blaming the PLC port. If the HMI shows periodic traffic but no responses and the PLC logs a port error, give the PLC’s communication configuration and port hardware closer scrutiny. When nothing on the segment can reach anything else and physical inspection reveals damage, the port or cabling becomes the prime suspect.

A simple way to keep thinking straight is to map symptoms to likely layers, then deliberately test each layer. The table below reflects patterns that appear across Control.com diagnostics, Siemens documentation, and field forum cases.

| Symptom on the floor | Likely layer at fault | Quick confirmation approach |

|---|---|---|

| HMI shows timeout alarms but engineering laptop talks to PLC normally | HMI configuration or driver, possibly security | Compare HMI channel settings with PLC project; check TIA Portal connection type and certificates; review HMI logs |

| Ping intermittently succeeds between HMI and PLC | Physical connection quality | Inspect and re‑terminate RJ45 ends; continuity test each conductor; wiggle cable and observe ping behavior |

| No ping in either direction; both devices powered | Cable or port hardware, or network isolation (VLAN/firewall) | Try a known‑good patch cable directly between HMI and PLC; bypass switches where possible; temporarily relax firewall rules on the HMI host |

| Serial TX LED blinking on PLC, no RX activity and PLC sets an RS‑232 error bit | PLC serial port settings or hardware | Confirm baud, parity, address, and protocol; test the PLC port with a loopback or another known‑good device |

| WinCC runtime connects for a few seconds then drops, engineering tool is stable | HMI runtime channel or driver | Review channel params, timeouts, and version; check for mismatched protocol stacks or security settings |

A Field‑Proven Diagnostic Workflow

Over time, I have converged on a workflow that lines up well with what Flextech Industrial, Xinje, Kinseal, Siemens, and AutomationDirect teach in their troubleshooting material. The exact tools differ between vendors, but the sequence is consistent: confirm physical health, validate configuration, leverage built‑in diagnostics, then escalate to advanced tools and hardware repair.

Start With Power, Ground, And Physical Connections

Nearly every HMI troubleshooting guide, including those from Flextech Industrial and Xinje, begins with basic hardware checks, and for good reason. A surprising number of “smart” failures trace back to very simple physical issues.

Confirm that the HMI and any associated communication modules have solid, correct power. Flextech recommends verifying input voltage with a multimeter, for example confirming a rated 24 VDC supply is actually present under load, not just open‑circuit. Look for loose terminal screws, frayed conductors, discolored insulation, or connectors that can be moved by hand. If you see burn marks, swelling on capacitors, or signs of overheating around the communication area, treat those as strong hints of internal hardware stress.

Check grounding and shielding quality. Several sources, including Kinseal and AutomationDirect’s C‑more Micro training material, emphasize that poor grounding contributes to intermittent or noisy communication, especially on serial ports. An HMI that shares a clean, solid ground reference with the PLC and network devices will tolerate industrial noise far better than one floating on questionable grounding.

Next, examine the communication cables themselves. Control.com’s article recommends visual inspection for pinches or cuts, particularly for Ethernet cables that may have been crushed, kinked, or run through tight conduits. With serial cables, look for bent or corroded pins and cracked shells. Where possible, reseat connectors and see if the behavior changes. If the issue disappears when you touch or support the connector, you have an underlying mechanical problem that needs addressing, not a mysterious firmware glitch.

Validate Port Configuration On Both Ends

Once you are confident the physical infrastructure is acceptable, configuration is usually the next failure point.

For serial ports, the C‑more Micro video from AutomationDirect is very explicit: confirm that you are wired to the same port the project thinks it is using, and that both devices share identical settings. Engineers occasionally configure a project for COM1 and wire hardware to a different port, leaving the HMI and PLC staring at each other across the panel with no actual conversation.

Beyond port selection, serial communications depend on matching parameters. The AutomationDirect training emphasizes that the C‑more Micro assumes eight data bits, so parity, baud rate, stop bits, and device address must all match the PLC’s serial settings. Host protocol choices must also align. In the Omron CP1E forum case, the engineer selected HostLink because it had worked before, while the manuals elsewhere discussed 1:N NT Link and then warned it was not supported by the NB HMI. This kind of protocol mismatch can generate port error bits and “No Response” alarms even when the wiring is perfect.

Ethernet configurations have their own traps. The Control.com article notes that duplicate IP addresses or incorrect use of TCP ports can produce intermittent communication. If your HMI and PLC both appear on a managed network, ensure that each device IP, subnet, and gateway are unique and appropriate for the segment. Remember that some installations use network address translation modules so that multiple machines can reuse the same local IP ranges. In those cases, the NAT configuration must properly isolate each machine; otherwise, HMIs and PLCs with identical local addresses can collide once traffic passes routers or gateways.

Finally, make sure you are using the intended protocol. Flextech and Xinje both emphasize validating that settings like Modbus TCP, EtherNet/IP, Profinet, or other protocols match the PLC project. A C‑more or Siemens HMI configured for Modbus TCP will not magically talk to a controller expecting Profinet I/O.

Use Simple Built‑In Diagnostics Before Advanced Tools

Before you reach for packet analyzers or deep logs, lean on the diagnostics your vendors have already provided. These tools are designed specifically for the hardware and often give clear, actionable information.

For Ethernet‑based connections, the humble ping remains a powerful first tool. The Control.com article recommends running ping from one device to the other in both directions. If responses are intermittent, suspect loose RJ45 terminations or marginal cable. If there is no response, try a known‑good cable directly between HMI and PLC to remove switches and patch panels from the equation. A sudden recovery with the new cable is a strong indicator of cable damage or prior electrical events that compromised insulation.

When basic connectivity looks intact but communication is still unreliable, packet sniffers such as Wireshark, as mentioned in that same Control.com reference, can expose duplicate IP addresses, port conflicts, or misconfigured NAT. You do not always need to dig into protocol payloads; sometimes just watching ARP requests and TCP resets is enough to pinpoint where the port’s traffic is going wrong.

Siemens SIMATIC CPUs provide another useful layer of diagnostics through their integrated web server. Documentation describes pages for diagnostics buffers, communication statistics, and PROFINET topology that can be accessed over a browser using the CPU’s IP address. On the Communication page, you can review interface parameters, packet statistics, and connection status for each configured channel. The Topology page shows which devices the PLC believes are connected. If the HMI does not appear where it should, you know you have a network‑level issue; if it appears but shows communication errors, the problem may be protocol or application‑level.

On the serial side, AutomationDirect’s C‑more Micro panels provide a loopback test mode. The manual and video explain that you can connect a simple loopback adapter—shorting specific pins, such as pins 3 and 4 on one serial port—then run a test that sends data out and expects it back immediately. The HMI displays counts of bytes sent, bytes received, and error counts. If sent and received counts rise together with negligible errors, the port hardware is likely healthy. If sent bytes climb while received stays at zero, you may be dealing with a bad port or bad loopback wiring. This type of built‑in test is extremely valuable for separating port failures from cable or PLC issues.

Finally, do not overlook diagnostic codes from middleware. AVEVA’s driver documentation associates conditions like “break between PLC and DIObject,” “node disconnected,” and “WinPlatform undeployed” with specific hexadecimal status codes. When you see such codes mapped to a particular HMI communication object, you can focus directly on the gateway node or object deployment state instead of taking apart every cable.

Isolate Cables, Ports, And Devices

With basic diagnostics in hand, the next step is isolation. The goal is to prove whether the communication failure follows the cable, the port, or the device.

Flextech Industrial recommends swapping suspect cables with known‑good replacements and, where possible, connecting the HMI to a test PLC or simulator. If the problem moves with the cable, you have a wiring or connector issue. If it follows the HMI regardless of which PLC you use, suspicion shifts toward the HMI port or its internal logic.

The Omron CP1E case shows another angle. The HMI was tried on different PLC ports, yet the PLC’s internal error bit for the RS‑232 port stayed asserted. In situations like this, testing the PLC port with a different device, such as a laptop running serial diagnostics, can help determine whether the PLC’s port is truly failing or both devices are misconfigured in the same way.

For Ethernet devices, temporarily connecting the HMI and PLC through a simple unmanaged switch or even back‑to‑back with a short cable can cut out the broader plant network. If communication stabilizes on this isolated link, you know that some upstream switch, router, or firewall is affecting your traffic.

Do Not Ignore Firewalls And Security Settings

Plant networks are increasingly protected by host firewalls and encrypted channels, and these can break HMI communications very effectively.

The Control.com article notes that, even after physical repairs, communication can still fail simply because firewall rules on the HMI host were changed during system updates. In that scenario, the solution was to review firewall configuration on the operating system and allow the TCP ports used by the PLC–HMI protocol. This is tedious work, but much faster than replacing good hardware.

Security configuration in engineering tools can also cause confusion. A social media post about TIA Portal from version 17 onward, for example, explains that Siemens now enables encrypted HMI–PLC communication by default. If the necessary certificates are not created and assigned correctly, or if the HMI is configured to use encrypted communication while the PLC expects a different mode, connections may fail or behave intermittently. The same post points out that for closed, non‑internet‑exposed networks, using a legacy (non‑encrypted) connection mode can simplify communication, as long as the user is comfortable with the risk trade‑offs.

The practical takeaway is that when you see a communication port that looks healthy at the wire level but refuses to carry application traffic, check both host firewalls and any encryption or certificate settings in your automation tools.

Recognize When The Port Hardware Has Actually Failed

Eventually, you will encounter ports that really are damaged. External signs include cracked housings, broken or loose connectors, and corrosion around the port, all mentioned by Xinje and Industrial Automation Co. Internally, repeated communication errors despite clean cabling and correct configuration suggest the transceivers or associated circuits are failing.

Repair and service providers such as DriveFix Electronics and Roc Industrial describe typical work they perform on HMIs: replacing damaged communication ports and connectors, repairing or replacing PCBs, and addressing power problems that may have damaged port circuitry. They emphasize comprehensive testing after repair, including communication checks, to ensure the ports function under load.

In my own work, when a port shows unrecoverable behavior despite passing loopback tests and configuration reviews, or when it exhibits intermittent faults tied to vibration or temperature, I weigh repair versus replacement. Kinseal and Flextech note that when repair cost approaches a significant fraction of a new unit, or when the model is obsolete, replacement may be the more reliable path. However, for critical or legacy HMIs, a qualified repair shop that understands industrial communication hardware can be invaluable.

Serial Port Failure Lessons From The Field

Serial links are still common between HMIs and smaller PLCs or drives, and they have their own characteristic failure modes.

The DL06 and EZ‑Automation panel case, where frequent “PLC COMMUNICATION TIMEOUT” errors appear even at modest baud rates and across multiple units, illustrates that serial performance problems are not always due to high scan times or controller overload. The PLC scan times cited were around 16 to 18 milliseconds, which is perfectly reasonable, yet communication timeouts persisted. This pushes the investigation back toward port configuration, protocol handling in the HMI, or perhaps noise and grounding issues on the RS‑232 connection.

In the Omron CP1E and NB HMI example, the recurring RS‑232 error bit and one‑way traffic from HMI to PLC highlight the importance of not trusting assumptions when swapping hardware. The engineer believed that all serial settings were copied to the new PLC, but something remained inconsistent enough to keep the port in an error state.

AutomationDirect’s loopback testing method for C‑more Micro panels is an excellent template for serial port diagnostics across vendors. When you internally loop the transmit and receive pins and send data, you eliminate the PLC and the external cable from the equation. If the HMI’s sent and received counts track each other with essentially zero errors, you can stop blaming the HMI port and focus on the cable or device at the far end. If they do not, you have strong evidence that the HMI’s serial hardware needs repair.

These cases underline a core principle: do not immediately assume a serial port is dead. Prove it with a methodical combination of configuration comparison, built‑in tests, and strategic substitution of devices.

Ethernet Port Failure And Network Layer Pitfalls

Ethernet brings higher bandwidth and better diagnostics than serial, but it also introduces more opportunities for misconfiguration and subtle port failures.

The Control.com article on HMI troubleshooting and maintenance lays out a sensible approach. When an HMI stops talking to a PLC over Ethernet, start with ping tests. Intermittent responses often mean poorly crimped RJ45 connectors or marginal wiring. Reseating connectors and using a voltmeter for continuity checks on each pin can reveal open or shorted pairs that cause erratic behavior.

When ping fails completely, especially after a period of normal operation, the article suggests that a previous electrical event such as a voltage spike or short may have damaged the cable. Swapping in a known‑good cable directly between the HMI and PLC is a quick, low‑risk test. If communication returns, replacing the damaged cable is the right move.

Network diagnostic tools, particularly packet capture utilities like Wireshark, are valuable for port‑level troubleshooting. As the Control.com piece notes, they can help identify situations where two devices inadvertently share the same IP address or attempt to use the same TCP port in conflicting ways. In systems using NAT, the same local addresses can legitimately exist in different machine cells, but only if the NAT configuration is correct. Misconfigured NAT can leak traffic or cause multiple HMIs and PLCs with identical local IPs to collide on the upper network, resulting in strange, intermittent failures that seem like port issues.

Siemens’ integrated web server and communication diagnostics materials reinforce that Ethernet ports must be considered as part of an overall communication path. The Communication diagnostics page on a SIMATIC CPU, for instance, shows interface parameters, statistics, resource use, and the status of each connection. If the HMI’s connection shows frequent drops, errors, or resource exhaustion, you can suspect either misconfigured timeouts, overloaded links, or port‑level problems on the PLC or HMI. The PROFINET topology view makes it easier to confirm that ports are physically and logically connected where you think they are.

A Siemens WinCC example, where the HMI runtime repeatedly connects and disconnects while the engineering tool remains stable, illustrates that Ethernet ports themselves can be fine while application‑level links are misconfigured. This again argues for using built‑in diagnostics to separate port hardware failures from channel configuration errors.

Designing For Fewer Port Failures

Repairing ports is necessary, but designing systems so they fail less often is better for everyone. The same themes that show up in troubleshooting guides translate directly into design and maintenance practices.

Kinseal and Xinje both stress environmental control. Communication ports on HMIs should be kept away from direct exposure to dust, moisture, and vibration as much as possible. Protective enclosures and vibration‑damping mounts extend not only the life of the touchscreen and display but also the life of the connectors and boards behind the ports.

Power quality is another critical factor. Kinseal recommends using surge protection and uninterruptible power supplies to reduce the risk of power‑related shutdowns and port damage. Ensuring that HMIs and PLCs share solid grounding reduces the likelihood of intermittent communication errors caused by noise.

Flextech’s step‑by‑step troubleshooting guidance highlights the value of disciplined documentation. Every time your team resolves a communication failure, capture the cause, remedy, and any contributing design weaknesses. Over time, this becomes a very practical design checklist: use better‑quality cables where you have repeated pin damage, relocate HMIs to reduce strain on ports, adjust grounding, or change the protocol configuration to something that better fits your environment.

On the software side, keeping firmware and communication drivers current is a simple but powerful preventive measure. DriveFix and other repair providers emphasize that they frequently see HMIs with corrupted software or outdated firmware that contributes to communication failure. Regular updates, tested in a controlled environment first, reduce the risk of bugs that only appear in specific traffic patterns or after long uptimes.

Security configuration should also be deliberate rather than accidental. Siemens’ note about encrypted communication in TIA Portal makes it clear that secure channels are the default now. Decide whether each application truly needs encrypted HMI–PLC communication and, if so, invest the time to set up certificates correctly. If the system is on an isolated, air‑gapped network, a simpler legacy connection may be acceptable, but that decision should be made explicitly and documented.

Working With Repair Partners

Even with excellent design and maintenance, some communication ports will eventually fail. Knowing when to involve a specialist can save your team time and reduce downtime.

Repair companies like Roc Industrial and DriveFix Electronics describe well‑structured processes focused on returning HMIs to full operating condition, including port functionality. Their services typically include evaluation, component‑level repair or replacement of PCBs, ports, and power supplies, followed by load testing and functional checks of display, touch, and communication ports. They maintain stocks of replacement components, which can be especially important for legacy or discontinued HMI models.

Industrial Automation Co. points out that not every failing HMI has to be scrapped. Many units can be repaired within a one‑ to two‑week window, and refurbished units are often available when immediate replacement is required. They highlight the importance of obtaining exact part numbers, communication options, and firmware revisions from the nameplate so that replacements integrate cleanly with existing PLCs and networks.

From an integrator’s perspective, I recommend bringing in repair partners early when you see repeated port issues on the same platform, or when the HMI holds valuable configuration that might need to be recovered from failing memory. Experienced repair houses often can clone or recover application data from faulted units, which can be the difference between a clean return to service and a painful re‑engineering effort.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I tell if the HMI port, the PLC, or the network is actually at fault?

The most reliable way is to change one piece at a time while watching what the communication diagnostics say. If you replace the cable with a known‑good one and the problem vanishes, you have a wiring issue. If you connect a test HMI to the same PLC and it communicates cleanly, suspect the original HMI’s port or configuration. Conversely, if multiple HMIs show similar problems with the same PLC, the PLC’s port or configuration becomes the likely culprit. Built‑in tools such as Siemens communication diagnostics pages, C‑more loopback tests, and status codes from drivers like AVEVA’s SP‑CDP help you see which side believes the link is broken.

When is it reasonable to switch a Siemens HMI–PLC link to “legacy” rather than encrypted communication?

A TIA Portal note explains that, starting with version 17, Siemens enables encrypted HMI–PLC communication by default, with certificates governing the secure channel. For systems that might be exposed to larger networks or where there are explicit security requirements, staying with encrypted communication is the right move. For simpler, closed plants where the PLC network is never routed to corporate or external networks, using a legacy connection can reduce complexity. The key is to make the decision consciously and document it, not to flip to legacy mode just because the encrypted link was not configured correctly.

When should I stop troubleshooting and send the HMI out for repair or replacement?

If you have confirmed good power, solid grounding, clean and correct cables, consistent configuration on both ends, and your built‑in diagnostics still show errors that follow the HMI rather than the PLC or network, you are likely dealing with an internal port or board failure. When the cost of the repair approaches a significant portion of a new unit, or when the HMI is obsolete and repeatedly failing, replacement becomes more attractive. When the HMI contains complex or poorly documented applications, a repair shop with cloning and recovery experience can be worth the investment before total failure makes data recovery impossible.

A failed HMI communication port can stop a line as effectively as a mechanical jam, but it does not have to become a guessing game. By treating port failures as layered problems, leaning on vendor diagnostics, and combining systematic isolation with sensible use of repair partners, you can turn “PLC not responding” from a long outage into a controlled, predictable recovery. That is the kind of disciplined troubleshooting that keeps you trusted as a long‑term project partner, not just a fire‑fighter.

References

- https://aichat.physics.ucla.edu/index_htm_files/textbook-solutions/6mKGbI/Hmi_Programming_Tutorial.pdf

- https://admisiones.unicah.edu/virtual-library/qodbQB/5OK107/c-more_hmi_programming-manual.pdf

- http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/65018/1/102437.pdf

- https://do-server1.sfs.uwm.edu/url/5R2S355988/edu/3R9S431/allen_bradley__hmi_manual.pdf

- https://www.plctalk.net/forums/threads/hmi-communication-problem.102456/

- https://www.automationdirect.com/videos/video?videoToPlay=Qz1UKU6gv0s&srsltid=AfmBOoqMhG_iVGLif-qbuPNz5J7bnI6flrm56bdO_z3pq8NbRonaferS

- https://drivefixelectronics.com/blog/comprehensive-guide-to-hmi-troubleshooting-and-repair

- https://www.kinsealhmi.com/info/common-human-machine-interface-hmi-failures-94009150.html

- https://www.piglerautomation.com/siemens-s7-1500-communication-errors-try-these-5-quick-fixes/

- https://www.rocindustrial.com/repair-page/ge-hmi-touchscreen-overnight-repair-troubleshooting-guide

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment