-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Import Logistics Services for DCS Equipment: Protecting Your Cutover From the Port Inward

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

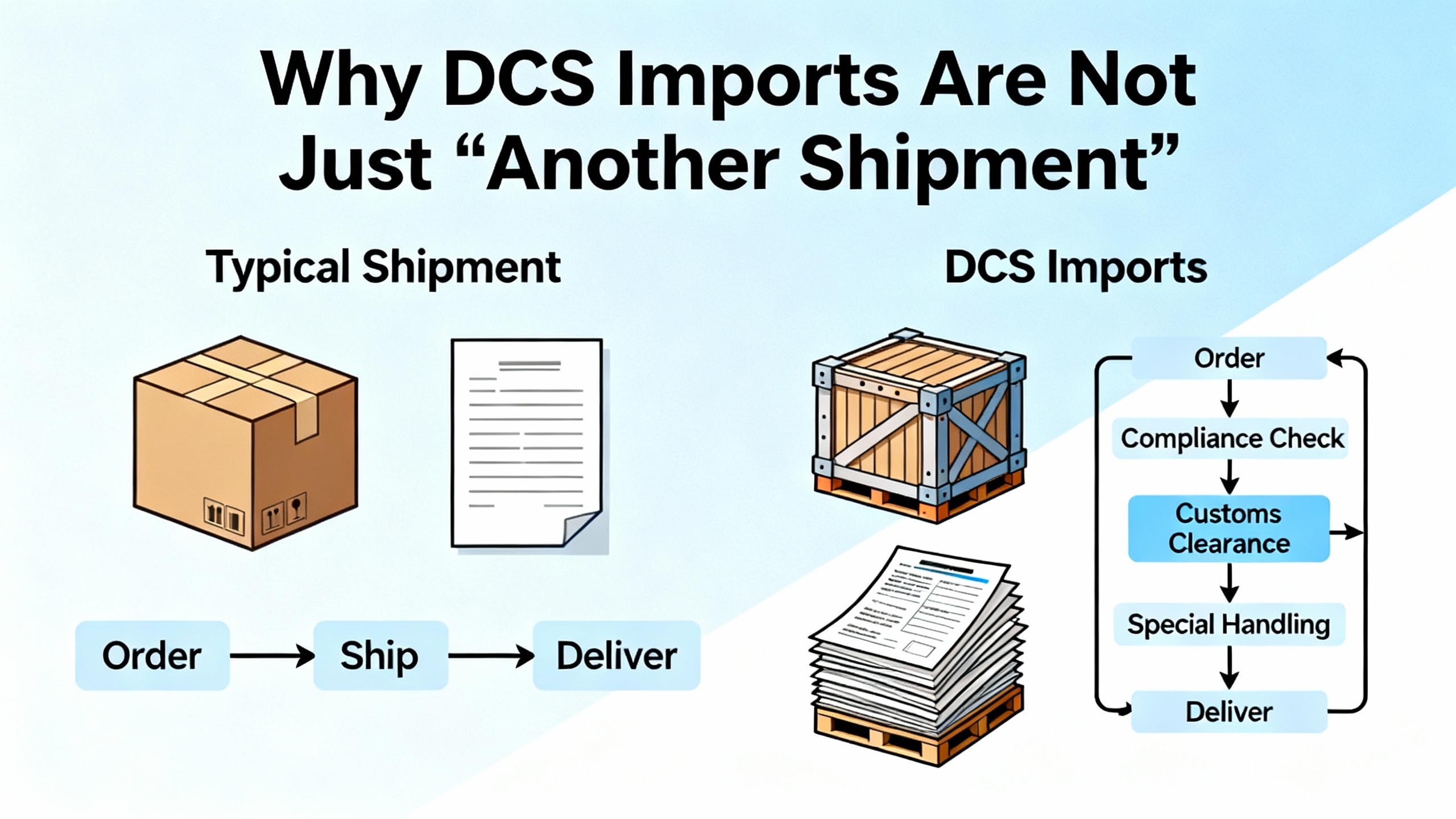

Why DCS Imports Are Not Just “Another Shipment”

Distributed control systems sit at the center of modern plants. As various industry sources point out, legacy DCS platforms are aging, increasingly obsolete, and in many cases have gone a decade or more without meaningful updates. When you finally secure budget for a DCS migration or expansion, imported hardware becomes the backbone of that upgrade: controllers, I/O racks, marshalling cabinets, servers, HMIs, network switches, and sometimes pre‑fabricated skids.

At the same time, DCS migration is inherently high risk. ISA, Control Engineering, and other practitioners emphasize that the most dangerous period is the installation and especially the cutover phase, when you move wiring and field devices from the old I/O to the new platform. If your imported equipment arrives late, incomplete, or damaged, the risk profile of that cutover changes immediately. In practice, the plant does not care whether the cause was a misrouted ship, a customs delay, or a missing cabinet door. Downtime is downtime.

In my own project work, the most painful scheduling crises have not come from configuration errors. They came from logistics issues that nobody owned: a cabinet sitting under inspection because commercial documents did not match, a shipment that was not registered properly in advance of loading, or parts detained because the importer relied blindly on the broker while ignoring the “reasonable care” obligations that U.S. Customs and Border Protection expects importers to meet. That is why import logistics services for DCS equipment must be built into the DCS project from the first planning document, not tacked on as a last‑minute shipping task.

What “Import Logistics Services” Really Means for DCS Hardware

When we talk about import logistics services for DCS equipment, we are not just talking about trucks and containers. A robust service scope spans several interdependent areas: documentation and compliance, freight execution, warehousing and staging, physical security, and financial control over duties and fees. Inbound Logistics describes international importing as the alignment of three flows: information flow, fiscal flow, and physical flow. For DCS projects, this mapping is very useful.

The information flow covers everything that customs authorities, ports, carriers, and internal stakeholders need to know. That includes commodity classification, country of origin, security programs such as C‑TPAT self‑assessments, and security‑related rules like the 24‑Hour Rule for ocean manifests. When forms, part numbers, and quantities are inconsistent between supplier, forwarder, and importer, delays follow. In many plants, there is still too much dependence on email, faxes, and spreadsheets, which makes reconciliation of DCS hardware shipments unnecessarily hard.

The fiscal flow covers supplier payments, freight charges, duties, and taxes. Modern importing practice, as highlighted in logistics and trade articles, expects importers to understand their total landed cost, including section‑based tariffs and special duties. For a multi‑million‑dollar DCS replacement, choosing the right duty strategy and avoiding penalties can free meaningful budget for spares and additional functionality.

The physical flow is the actual movement and handling of crates, pallets, and containers. For standard consumer goods, a delay at the port may hurt customer service but rarely puts plant safety at risk. For DCS upgrades, a delayed or mishandled controller cabinet can undermine an entire cutover window. That is why import logistics services for DCS equipment need to be engineered with the same discipline you apply to control narratives and safety instrumented functions.

DCS Modernization Demands Logistics Discipline

Multiple technical sources on DCS modernization converge on a common message: the era of “run it until it fails” is over. Obsolescence risk, cybersecurity gaps, and lack of spares make modernization a business necessity. Strategic planning frameworks such as front‑end loading (FEL) break projects into conceptual, capital planning, and final funding phases, with increasing detail and tighter cost/schedule accuracy at each step.

In FEL work, teams typically focus on migration strategies, such as phased migration versus rip‑and‑replace, hot versus cold cutover, and horizontal versus vertical replacement. The best practice is to use the early phases to identify risks in safety, cybersecurity, downtime, and resource availability. What I see too rarely is import logistics listed as a named risk category in the FEL risk register. Yet the same guidance that tells you to analyze network traffic and data integrity early applies equally well to ocean transit time and port dwell.

The documentation you are encouraged to clean up before equipment arrives—updated P&IDs, loop sheets, panel and rack drawings, cable schedules, and wiring verification—should be mirrored on the logistics side by clean commercial documentation, consistent part and serial number mapping, and advanced sharing of packing lists and shipping plans with your forwarder and broker. When the new DCS arrives on site, the goal is that nothing about the shipment surprises the plant. That outcome does not happen by accident.

Ports, FTZs, and Warehouses: Where to Stage Your DCS Hardware

DCS equipment for a major unit or plant can fill multiple ocean containers and domestic trailers. Getting that hardware from origin factory to actual rack rooms requires choices about port of entry, warehousing strategy, and possibly use of a U.S. Foreign Trade Zone.

Foreign Trade Zones, as described in trade automation guidance, are secure areas under U.S. Customs and Border Protection supervision that are treated as outside U.S. customs territory for duty purposes. They allow you to defer, reduce, or in some cases eliminate customs duties on imported goods. When you are importing a large volume of control hardware and spares, using an FTZ warehouse near your port can align duty payment with actual consumption of parts in the field, rather than paying everything upfront when containers land.

General import/export warehousing practice, described in warehousing best‑practice articles, emphasizes locating warehouses near ports, airports, or major transport hubs. This reduces inland transit time and allows you to stage goods quickly for final delivery. Those same sources stress that technology, such as a warehouse management system, is essential for accurate tracking, and that strong relationships with freight forwarders and customs brokers are critical. For DCS equipment, I recommend staging in a facility that can track serial numbers, environmental conditions, and test or inspection status, not just pallet counts.

Emergency management guidance from organizations like FEMA also adds a useful conceptual layer. Their distribution management planning breaks networks into warehouses, staging areas, and points of distribution, with clear roles, capacity plans, and scalability from small to large events. A DCS migration is not a disaster, but you can adapt that logic: port warehouse and FTZ as central warehouses, near‑site staging as the staging area, and control rooms as final distribution points. When you design the logistics network that way, you are less likely to overload a single site with unexpected inbound crates a few days before a turnaround.

The differences between key storage options can be summarized as follows.

| Storage option | How it works for DCS hardware | Main advantages | Main trade‑offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard port warehouse | Hardware cleared through customs, stored near port until needed | Simple setup, straightforward billing, quick access to local carriers | Duties paid immediately, less flexibility on timing |

| FTZ warehouse | Hardware admitted into FTZ, duties paid when parts leave zone for U.S. use | Defers or reduces duties, supports long staging periods | More compliance steps, requires FTZ‑capable operator |

| Inland warehouse | Hardware cleared and moved closer to plant before storage | Shorter final mile, less dependency on port congestion | Longer initial inland haul, may complicate rerouting |

The right combination depends on project size, duty rates, and the time between equipment arrival and installation. For a multi‑year phased migration where hardware and spares will trickle into service, FTZ staging can make sense. For a tight turnaround where everything will move from port to plant within weeks, a standard port warehouse with strong visibility may be sufficient.

Heavy Hardware, Transloading, and Container Strategy

Many DCS projects include heavy or dense shipments: steel racks, pre‑wired marshalling panels, or combined skid packages that include piping and instrumentation. The way you load and unload ocean containers for those materials has a direct cost and schedule impact.

Transloading, as described by experienced import logistics providers, is the transfer of freight from one transportation mode to another at a port, rail yard, or warehouse hub. For U.S. imports, the common pattern is moving goods from ocean containers into domestic dry vans or flatbeds. This practice is particularly valuable when receivers cannot handle ocean containers directly or when domestic highway weight limits make it impractical to send fully loaded containers inland.

One proven model is heavyweight transloading. In this approach, shippers deliberately load ocean containers above the typical U.S. road limits, sometimes around 55,000 lb and in some cases even a bit higher, instead of staying near the more common 44,000 lb domestic assumption. At the port, a transload facility then splits the contents into two or more legal‑weight trailers for inland delivery. Industry case studies cited by specialists report that this can allow more than 30 percent additional freight by weight per ocean container and can reduce total freight cost by around 20 percent, while also accelerating container turn‑in and reducing detention.

Even when you are not pushing weight limits, transloading offers benefits for DCS hardware. A carefully equipped facility can consolidate mixed shipments for several plant sites, stage materials by cutover phase, and load trailers in the sequence you intend to unload at the plant. Logistics guidance on distribution centers emphasizes pre‑planned truck loading sequences to reduce delivery time and fuel use; the same principle applies when you want the first cabinets off the trailer to be the ones you install first.

There are trade‑offs. Moving heavy containers directly from port to consignee using specialized trucking and permits avoids double handling, but it tends to be less flexible when you need to split the shipment for different plants or different phases. Transloading introduces an extra handling step, which must be managed carefully to avoid damage. For DCS equipment with sensitive modules, you should demand clear handling procedures, appropriate lifting tools, and detailed inspection reports at the transload site.

A simple way to view the options is to compare them side by side.

| Approach | When it fits DCS equipment | Benefits | Key risks to manage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct inland move in container | Single destination, moderate weight, consignee can unload containers | Fewer handling steps, simpler coordination | Possible underutilized container capacity |

| Heavyweight transloading | Dense freight, multiple inland destinations, port facility available | Higher payload per container, cost savings, better staging | Extra handling, requires capable transload partner |

In practice, the decision should be made early in the project, when you are still designing packing lists and crate dimensions, not at the time the first container leaves the factory.

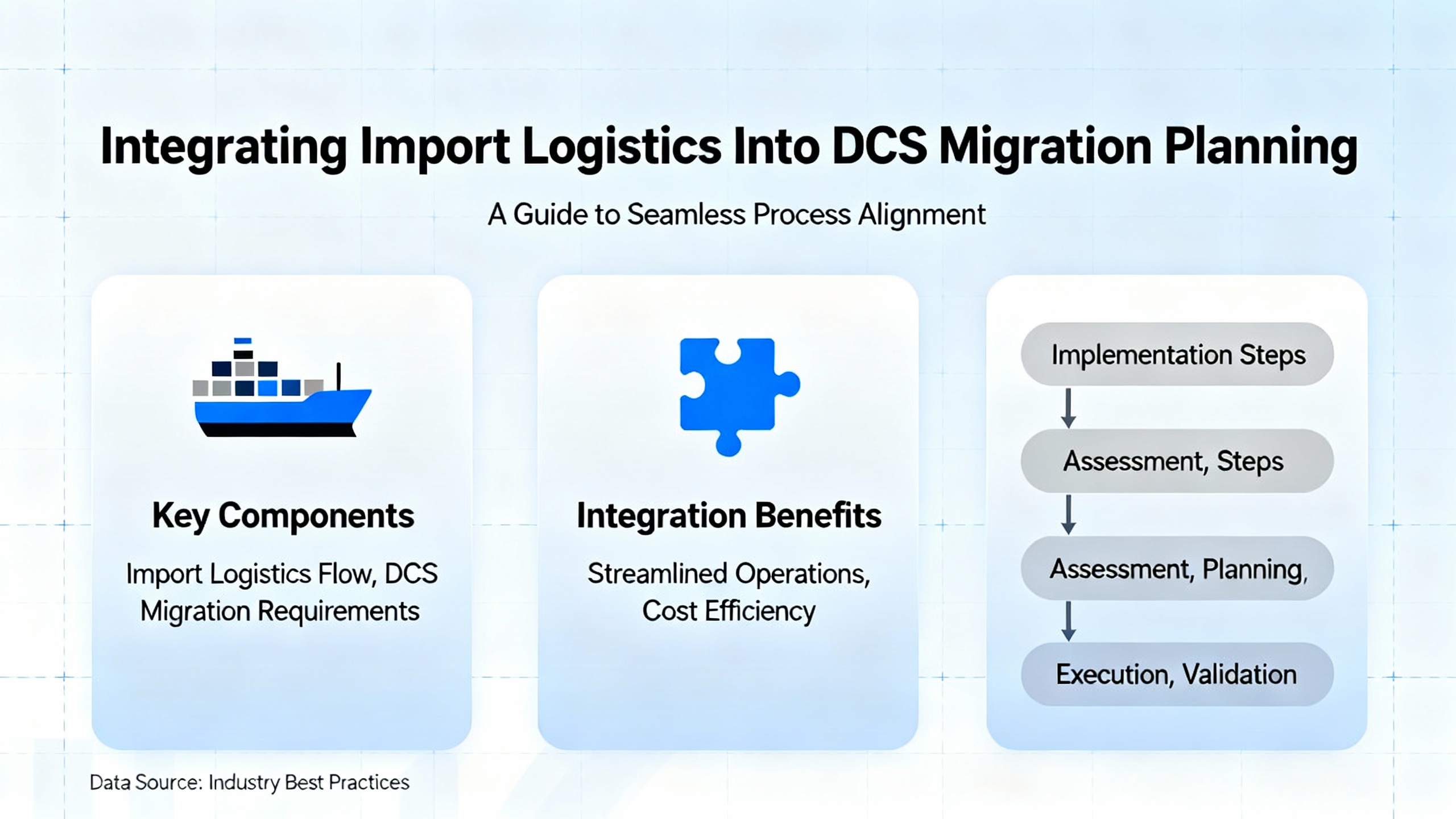

Integrating Import Logistics Into DCS Migration Planning

The most successful DCS migrations follow structured planning approaches. FEL methodologies divide the work into conceptual, capital planning, and detailed funding phases, with explicit risk analysis in each phase. Modernization strategy work from sources like IEB Media highlights key decisions such as replication versus innovation, rip‑and‑replace versus phased migration, and hot versus cold cutover. All of those choices have cost, risk, and downtime implications.

What these frameworks imply, even when they do not say it outright, is that import logistics events are project milestones that must be reflected in the schedule and risk plan. During the conceptual and capital planning phases, you should treat the international supply chain as part of your critical path. That means understanding whether your chosen DCS vendor ships from overseas, whether panel shops are local or overseas, what the typical ocean transit time is, and how long customs clearance and port dwell usually take. Inbound Logistics warns that failure to plan explicitly for on‑the‑water and customs‑warehouse time can drive stockouts or last‑minute dependence on premium freight. In a DCS context, that can translate into delayed FAT, rushed installation, or schedule compression right before cutover.

When a Control Engineering article recommends reverse‑engineering the legacy control system and defining a realistic cutover strategy, the implied precondition is that the new system is physically present, checked, and staged. Factory acceptance tests and site acceptance tests are also timeline anchors. These tests depend on imported equipment arriving in time, with the right configuration and no missing modules. Your import logistics provider must understand these milestones so that they can plan vessel selection, port routing, transloading, and final delivery accordingly.

Risk assessment guidance for DCS migrations stresses early identification of risk areas such as safety, downtime, network traffic, and cybersecurity. I advise clients to add at least three logistics‑related risk entries: import documentation errors, carrier or port disruption along the chosen trade lane, and delays caused by security programs or customs inspections. The “top importing do’s and don’ts” guidance in trade articles suggests cross‑functional triage teams that include supply chain, legal, finance, and compliance to track geopolitical and regulatory risk. For a DCS project, that team should be aware of your go‑live dates and be prepared to act if the chosen port experiences strikes, congestion, or new regulatory constraints.

Compliance, Security, and High‑Consequence Shipments

Security expectations for imports have changed significantly in the last two decades. After major security events, U.S. Customs and Border Protection shifted to a security‑first model, with programs such as the Cargo Security Initiative and C‑TPAT that push risk assessment outward to foreign ports and ask companies to self‑assess and harden their supply chains. Trade practitioners note that regular importers who ignore these programs often face more inspections, higher transport costs, and longer cycle times.

For DCS equipment, this matters in two ways. First, any shipment delay caused by security holds or documentation discrepancies impacts your cutover schedule. Second, in many industries, control systems are part of critical infrastructure or defense programs. Security cooperation documentation from the U.S. Department of Defense describes structured approaches for shipping classified or sensitive materials, involving Designated Government Representatives, transportation plans, and vetted freight forwarders with facility security clearances. Where DCS hardware is part of such programs, import logistics must cope not just with customs compliance but also with information and material protection rules that come from organizations such as the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency.

Even when your project is purely commercial and unclassified, control system migration guidance stresses the cybersecurity dimensions of DCS upgrades. Industry bodies such as ISA and NIST emphasize the need to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of control systems. While those frameworks are usually applied to networks and software, the same principles apply to physical shipments. You do not want a cabinet to be opened, swapped, or tampered with in transit. Selecting logistics providers who participate in recognized security programs, follow documented chain‑of‑custody practices, and can pass audits is not an optional luxury for critical control hardware. It is part of safeguarding the integrity of your new system.

Selecting Logistics Partners Who Understand DCS

A recurring theme in logistics and import management literature is the importance of choosing the right third‑party partners. Importers frequently rely on freight forwarders, consolidators, customs brokers, and third‑party logistics providers to hit tight shipping windows, manage documentation, reroute around disruptions, and navigate customs rules. However, legal frameworks such as the Customs Modernization Act make it clear that the importer, not the broker, bears ultimate responsibility for correct classification and compliance.

That means you need partners who can execute, but you also need internal oversight. Trade articles advise due diligence on providers’ financial stability, material‑handling practices, storage capabilities, document accuracy, and communication effectiveness. They also recommend formal service level agreements that define roles, performance metrics, and problem‑prevention mechanisms, followed by ongoing measurement of performance such as document handoff times and clearance cycle times.

For DCS equipment, I look for logistics partners with very specific capabilities. They must have demonstrated experience with similar heavy, high‑value, and sometimes delicate technical shipments. They should be able to consolidate and label crates in a way that lines up with control system documentation: cabinet tags, rack IDs, and I/O segment names. Distribution center optimization guidance from third‑party logistics providers underlines the value of structured warehouse layouts and placing high‑turnover items in accessible areas. Applied to DCS equipment, that suggests a warehouse that can segregate materials by cutover unit, outage window, or plant area, rather than stacking everything by arrival order.

Technology investments also matter. Articles on distribution center improvement emphasize the importance of warehouse management systems, ERP integration, and handheld data collection to reduce errors and increase productivity. For a DCS project, that translates into real‑time visibility of which cabinet is in which location, which pallets have cleared customs, and which parts are on a specific truck headed for the plant. Without that transparency, DCS cutover teams can waste precious outage hours just searching for the right components.

Practical Planning Moves for Your Next DCS Import

Pulling these threads together, there are several practical moves that, in my experience, make DCS import logistics much less painful.

Start by mapping your DCS hardware bill of materials to logistics units. Identify which items will ship as complete cabinets, which as loose cards, and which as pre‑fabricated skids. For each, decide whether they will be palletized, crated, or containerized, and how they will be labeled. This mapping should align with your updated P&IDs, loop diagrams, and rack drawings. The same discipline that standards bodies recommend for control documentation should govern your packing lists and labels.

Next, overlay your FEL schedule with realistic international transit and clearance timelines. Use data from your logistics partners about typical ocean transit times, manifest cutoffs, and customs clearance durations. Remember that vessel operators often require documentation at least a day before loading, and some ports want manifests 24 to 72 hours in advance. If your project schedule assumes that you can order hardware and see it at the plant a week later, the import reality will quickly correct that assumption.

Then, decide on your port, warehouse, and possible FTZ strategy at the capital planning stage, not after placing purchase orders. Work with your logistics partners to evaluate port congestion, labor conditions, and alternative gateways. Trade guidance warns that merely shifting from one coast to another can sometimes move bottlenecks rather than remove them. For DCS equipment, the right answer might be a less glamorous port that offers consistent performance rather than the absolute shortest ocean leg.

At the same time, design your duty and compliance strategy. If you expect ongoing imports of spares and incremental cabinets over several years, evaluate whether FTZ warehousing offers enough duty deferral or reduction to justify the added process overhead. If your DCS equipment is subject to special tariffs or export control restrictions, involve trade compliance experts early. Industry examples show that proactive use of trade programs and exclusions can save significant amounts in duties, which can be reinvested into better redundancy or long‑term support contracts.

Finally, build import logistics into your risk and contingency planning. Cross‑functional teams that already monitor political, regulatory, and supply chain risk for other imports should explicitly include DCS projects in their scope. Contingency plans might include alternative ports, backup carriers, or even pre‑planned use of premium modes for critical spares if a key container is delayed. Disaster response guidance recommends planning for scalable network configurations and transitions back to normal supply chains; the parallel here is planning for how you will continue safe plant operation if a migration phase is delayed by a shipment problem, and how you will resume your original migration path once the issue is resolved.

Short FAQ: Where Logistics and DCS Projects Usually Collide

Why do DCS imports so often cause schedule surprises, even when the hardware itself is well specified? Trade and control engineering sources both suggest the same root cause: teams treat logistics as an afterthought. Schedules are built around engineering and installation hours, not around ocean transit time, customs clearance, and port or warehouse capacity. When those assumptions collide with real‑world shipping and security rules, there is no slack left.

Is it worth building Foreign Trade Zone or transloading capabilities just for one major DCS project? That depends entirely on the scope and profile of your imports. Industry experience with heavyweight transloading shows real cost and utilization benefits when you have high‑density freight and multiple inland destinations. FTZs make the most sense when duty rates are high or when you will stage hardware for long periods. For a small, single‑site DCS upgrade with modest duties, the complexity may not pay off. For a multi‑site, multi‑year modernization with large imported content, it often does.

Who inside the organization should own import logistics for DCS projects? Guidance from both automation and logistics communities is clear that siloed ownership is a problem. Corporate supply chain or logistics typically owns carrier and broker relationships, while site engineering owns the DCS scope. The most reliable migrations are the ones where these groups plan together from FEL onward, possibly with support from a system integrator who understands both the control system and the import logistics landscape.

Over the years, the projects that went smoothly were not those with zero surprises. They were the ones where the team treated the DCS hardware flow from factory to panel as part of the control strategy itself. If you bring the same rigor to import logistics services that you bring to your process safety and control design, your next migration will be far less about firefighting and far more about quietly delivering the uptime and reliability you promised.

References

- https://www.bis.gov/media/documents/best-practices-preventing-transshipment-diversion

- https://www.businessdefense.gov/icie/ic/docs/def/Guide-to-International-Acquisition-and-Exportability_mjv.pdf

- https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_distribution-management-plan-guide-2.0.pdf

- https://blog.isa.org/10-essentials-successful-upgrade-dcs-migration

- https://www.techwem.com/article-detail.html?slug=successful-dcs-migration-planning

- https://www.3pllinks.com/post/5-practical-tips-to-improve-your-distribution-center-operations

- https://www.controleng.com/effective-process-control-system-migration-part-1-planning-advice/

- https://www.ctp-inc.com/articles/foreign-military-sales-fms-versus-direct-commercial-sales-dcs

- https://samm.dsca.mil/chapter/chapter-7

- https://www.fcbco.com/blog/distribution-supply-chain-insights

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment