-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Worldwide Delivery Solutions for Automation Components

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

When you work in industrial automation and controls, “shipping a part” is never just shipping a part. A misrouted drive or a delayed servo motor can idle a production line that burns through thousands of dollars per hour. Over the last couple of decades working as a systems integrator, I have seen beautifully engineered automation projects undermined by weak logistics and poorly understood export rules.

Worldwide delivery for automation components is its own discipline. It lives at the intersection of export controls, customs classification, dangerous goods handling, carrier strategy, and logistics automation. In this article, I will walk through how serious operators are approaching global delivery for drives, PLCs, sensors, robots, and other critical hardware, drawing on established guidance from organizations such as the Bureau of Industry and Security, major universities’ export control offices, and specialized logistics and export-automation providers.

The goal is pragmatic: keep your plants running, keep regulators off your back, and keep your global customers supplied without turning your export department into a permanent fire drill.

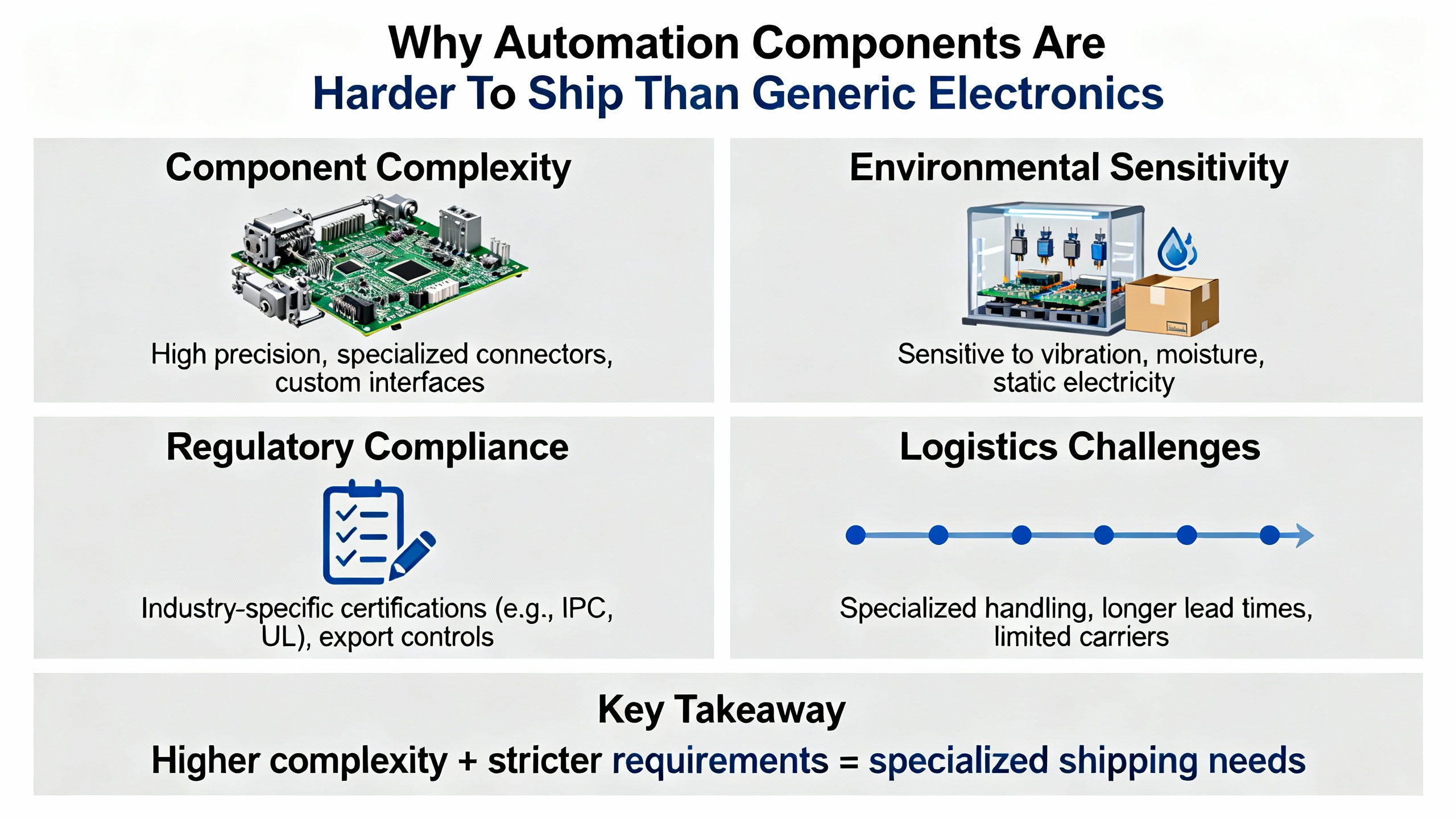

Why Automation Components Are Harder To Ship Than Generic Electronics

If you have ever tried to move a 10,000‑pound metal stamping press across borders, you already know why industrial shipments are different. Heavy-haul carriers, custom crating, riggers, and route planning with permits are just the starting point, as highlighted in guidance from ShipERP. A mistake here does not just cause a late delivery; it can damage multimillion-dollar assets and trigger expensive freight claims.

At the other end of the spectrum, automation components are often physically small but operationally critical. A drive, a safety PLC, or a vision sensor can stop a production line just as effectively as a failed transformer. These parts are frequently high-value, fragile, and time-critical. During COVID-era disruptions, for example, shortages of essential automation components showed how fragile the global supply chain could be, as discussed by PLC Automation Group. At the same time, remote work and social distancing pushed factories to automate faster, piling even more demand onto an already strained parts pipeline.

The global nature of automation supply chains compounds the problem. Manufacturers source subcomponents worldwide, assemble in multiple regions, and ship to customers in dozens of countries. That means you are dealing with export control regimes, customs classifications, and product certifications in overlapping jurisdictions, while customers expect near real-time tracking and short lead times.

Worldwide delivery solutions for automation components therefore have to solve three problems at once: physically moving unusual freight, complying with dense regulatory frameworks, and maintaining visibility and speed despite constant disruption.

Compliance First: Building A Legal Foundation For Global Delivery

In automation, you can outsource logistics tasks, but you cannot outsource legal responsibility. Guidance from the Bureau of Industry and Security, Indiana University, Northwestern University, and other export-control offices is consistent on one point: any shipment of a tangible item from the United States to a foreign destination is an export, even if it is temporary, loaned, or only used for research. Treating exports casually is how firms end up with seized goods or seven‑figure penalties.

Exports, ECCNs, and the “NLR” Trap

The backbone of export compliance is classification. Under the Export Administration Regulations, every item is either controlled under a specific Export Control Classification Number (ECCN) or falls into the general “EAR99” bucket. Many automation parts can be shipped under the status “No License Required,” but that is not something you assume; it is something you verify.

Industrial Automation Co. notes that dual‑use automation hardware is especially risky. Servo motors over certain power thresholds and PLCs with embedded encryption can fall into 600‑series ECCNs or even International Traffic in Arms Regulations categories if there is a defense angle. Those items can require licenses instead of simple “NLR” treatment. Misclassification is not a rounding error. According to Industrial Automation Co., fines can exceed $1,000,000 per violation, and classification errors are a common trigger.

The practical playbook is straightforward, even if the details are not. Confirm ECCNs with the manufacturer when possible. When that is not available, use structured processes such as the Commerce Department’s SNAP‑R classification requests, and lean on internal or external export-control specialists. University guidance from Indiana and South Alabama emphasizes that many items casually assumed to be EAR99 are not; automation OEMs and integrators see the same pattern in practice.

HS and HTS Codes: Getting Customs Right

Parallel to ECCN, every item needs a Harmonized System code for customs. For many automation components related to heavy equipment, HS Code 8431.49 is relevant; ShipERP calls out this code as covering parts and components for earth‑moving, mining, and construction equipment such as crane components, hydraulic systems, and track assemblies. Whether your part falls under that code or another, the principle is the same: customs authorities use HS and Harmonized Tariff Schedule codes to set duties and determine admissibility.

Incorrect codes can generate the usual pains: delays, unexpected duties, and additional scrutiny. From a systems-integrator viewpoint, the more damaging effect is unpredictability. When a “simple” drive shipment gets stuck at a border for reclassification, all your carefully built commissioning schedules go out the window.

Dangerous Goods: Lithium, Magnets, and Hidden Traps

Automation components often hide dangerous goods in plain sight. Embedded lithium batteries in HMIs and controllers, strong magnets in servos and encoders, and certain chemicals in sensor cleaning kits are all common triggers for IATA and IMO Dangerous Goods rules. Industrial Automation Co. cites a case where a batch of twelve servos with strong magnets had to be rerouted because they exceeded magnetization limits for air transport, racking up more than $14,000 in extra costs.

The lesson is simple and painful: screen every product line for hazardous materials early, and keep Safety Data Sheets current. For air shipments in particular, getting dangerous goods declarations right is non-negotiable. Otherwise, your “express” shipment ends up parked on the tarmac while your customer’s plant sits idle.

AES and EEI: When You Must File

For U.S. exporters, the Automated Export System and Electronic Export Information are unavoidable in most serious automation programs. ShipERP highlights the rule under Foreign Trade Regulations: when the value of a shipment under an individual Schedule B number exceeds $2,500, you must file EEI through AES. Northwestern University’s compliance office further notes that shipments of items on the Commerce Control List to countries such as China, Russia, or Venezuela require EEI regardless of value, unless a narrow exemption applies.

In practice, this means your shipping or export team needs a repeatable way to decide whether to file, collect the data, and interact with carriers. Northwestern’s and South Alabama’s guidance is clear that only trained export-control staff can determine whether an exemption applies. When EEI is required, you work with the carrier to file and obtain the Internal Transaction Number, and that ITN must appear on your commercial documents.

Automating this step pays off quickly. ShipERP’s ShipAES and similar tools embed EEI filing inside ERP environments, reduce manual data entry, monitor exports in the background, and enforce regulatory rules. For a high-volume automation parts business, that kind of automation can transform export filing from a nerve‑wracking spreadsheet exercise into a reliable background process.

Sanctions, Restricted Parties, and Audits

Export violations are not limited to misclassified motors. Northwestern University, Indiana University, and South Alabama all stress that shipping to restricted parties or embargoed destinations without the right license is equally serious. Screening customers, end users, and intermediaries against consolidated restricted-party lists is now a standard step, not a “nice to have.”

Freight forwarders are on the hook as well. Bureau of Industry and Security freight‑forwarder guidance explains that forwarders and exporters share responsibility for preventing illegal exports. Written Shipper’s Letters of Instruction, clear definitions of who files EEI in routed versus non‑routed transactions, and meticulous recordkeeping under 15 CFR 762 are all part of a defensible process.

The practical takeaway for anyone shipping automation components worldwide is that you need institutional discipline. Treat export control review as a standard step for international shipments, not a special-case exception. Universities advise initiating export control reviews several weeks before shipping hazardous or controlled equipment; industrial firms should adopt similarly conservative lead times for complex movements.

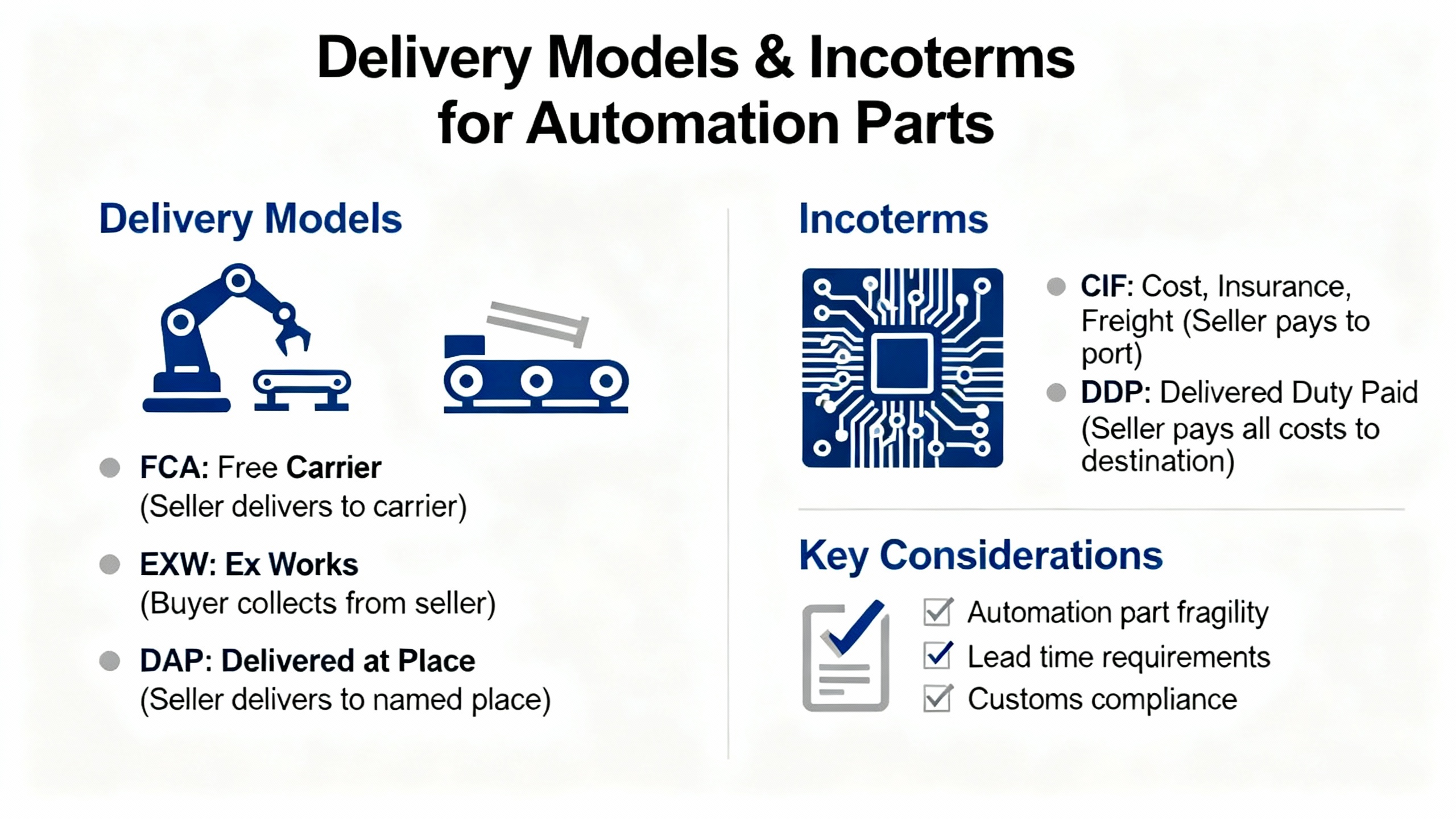

Delivery Models and Incoterms That Actually Work For Automation Parts

Once you know what you are allowed to ship and how to document it, the next question is who owns risk and cost at each step. Incoterms, defined by the International Chamber of Commerce, are the language we use to answer that question. They describe which party is responsible for transport, insurance, customs clearance, and duties.

For automation components, choosing the right term is the difference between a controlled, predictable global delivery program and a constant argument about surprise fees and responsibilities.

DAP, DDP, and EXW In Real Life

In automation projects, three patterns show up frequently: Delivered at Place, Delivered Duty Paid, and Ex Works.

Under a Delivered at Place arrangement, the seller handles most of the logistics, including export and international transport, and delivers the goods to a named place in the destination country. The buyer takes over for import clearance and duty payment. This model works when the customer has strong in‑country customs capabilities and prefers to control duties and taxes locally.

Under Delivered Duty Paid, the seller takes on almost everything, from export clearance through import clearance and duty payment, delivering the goods ready for use at the buyer’s site. For urgent replacement parts, Industrial Automation Co. notes that DDP via express carriers like DHL or FedEx is often the right answer. The carrier handles customs brokerage and export filings, and while you pay a premium for the service, the cost pales in comparison to production downtime that can easily exceed $5,000 per hour.

Ex Works sits at the other extreme. The seller makes the goods available at their facility, and the buyer arranges everything else. In theory, this minimizes the seller’s logistics burden. In practice, it is often a poor fit for mission‑critical automation components, especially when buyers lack export-control expertise or when the seller cares about consistent service levels.

A simple way to think about these models is summarized below.

| Model | Who Controls Export and Main Carriage | Pros For Automation Parts | Main Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAP | Seller exports and transports, buyer imports | Balanced control; seller manages complex routes, buyer manages local taxes | Misaligned expectations on duties and clearance time |

| DDP | Seller manages export, freight, and import duties | Maximum predictability for the buyer; strong for urgent replacements | Seller bears regulatory and cost risk; requires strong compliance processes |

| EXW | Buyer handles export and all transport | Minimal logistics workload for seller | High risk of non‑compliance or delays if buyer is inexperienced |

For worldwide delivery solutions, I generally see DAP or DDP as the most workable defaults for automation hardware, with EXW reserved for sophisticated buyers who explicitly want control.

Flat-Rate Programs and One-Stop Export Partners

A more recent trend in the automation components space is the use of flat-rate shipping programs and one‑stop export partners. Automation Components, LLC, for example, offers flat UPS rates for most online standard orders: a single charge for UPS Ground within the continental United States, higher flat rates for heavy ground shipments, and defined rates for next‑day, two‑day, and three‑day options. Similar flat‑rate structures cover Canadian destinations and broader international shipments, with special handling for heavy consignments.

The advantage is predictability. As a project partner, when you know that a UPS Ground shipment within the United States is going to cost a defined amount and that heavy shipments have a fixed “heavy” rate, you can bake those costs into project budgets and service agreements. Overweight or oversize shipments may still incur surcharges, but the majority of smaller spares and components follow a known pattern. ACI’s policy of charging only when items actually ship also aligns with how integrators manage project cash flows.

Industrial Automation Co. takes a slightly different tack, positioning itself as a one‑stop U.S. inventory and export hub for brands like ABB, Siemens, Mitsubishi, and Allen‑Bradley. By keeping stock domestically and offering same‑day shipping from its warehouse, combined with export documentation support and a two‑year warranty, it allows foreign buyers to treat the company as a trusted U.S. sourcing and logistics partner rather than dealing with multiple OEM export processes.

When you design a worldwide delivery solution, using partners like these lets your engineering team stay focused on specifying and commissioning, while your logistics playbook relies on standardized, well‑understood shipping behaviors rather than ad‑hoc negotiation.

Temporary Movements, Demos, and Repairs

Not all cross‑border movement is a sale. Automation projects often involve demonstration equipment, loaners, and repair‑return cycles. For these cases, Industrial Automation Co. and export‑control offices highlight two useful tools: ATA Carnets and duty‑free reentry.

For temporary exports used in demos or short-term projects, ATA Carnets classify goods as temporary imports and can help avoid full duties and local certifications. For repair and warranty returns, U.S.-origin goods may qualify for duty‑free reentry under U.S. Customs Form 3311 if they come back within two years. Properly labeling boxes with language such as “American Goods Returned – No EEI Required (30.37(a))” can save up to a quarter of the shipment value in duties and brokerage fees.

The technical details are best handled with customs brokers or trade counsel, but the operational implication is clear: build explicit processes for demo and repair shipments into your worldwide delivery model, instead of treating them as one‑off exceptions.

Using Technology To Design Reliable Worldwide Delivery

The physical and legal frameworks described above are necessary but not sufficient. To make worldwide delivery of automation components reliable at scale, you need automation in your logistics itself. Several credible sources, including ShipERP, Creative Logistics, Erbis, Wisor, NetSuite, and others, outline how shipping automation, warehouse automation, and supply chain automation interlock.

Shipping Automation and Multi-Carrier Execution

Shipping automation software has matured significantly. Solutions like ShipERP Cloud and InfoShip, for instance, integrate with ERP platforms to manage label generation, carrier selection, and documentation in a single workflow. ShipERP recommends choosing transport mode based on size, weight, urgency, and handling needs, and then letting a multi‑carrier engine shop real‑time parcel and LTL rates across carriers. The system applies rules, creates labels, and generates export documents automatically.

The benefits show up both in cost and reliability. In the A.O. Smith case cited by ShipERP, automated shipping and real‑time carrier integration improved shipping speed, increased capacity without adding manual labor, and provided real‑time tracking and automated shipment updates.

When you are shipping critical drives or PLCs to plants around the world, the ability to automatically select the best service level for a “line‑down” emergency versus a routine replenishment is invaluable. Air freight for true emergencies, optimized ground or ocean services for planned moves, and automatic export documentation all flow from the same rules engine.

Warehouse Automation: Making Parts “Ready To Ship”

Logistics automation in the warehouse is just as important. NetSuite’s warehouse automation overview points out that automation typically starts with a warehouse management system plus digital data capture technologies such as barcode scanning and RFID, integrated with ERP. These systems keep inventory records accurate and minimize manual data entry.

From there, more advanced physical automation comes into play. Goods‑to‑person systems, automated storage and retrieval systems, conveyor systems, pick‑to‑light, and autonomous mobile robots reduce walking time and increase picking speed, in some cases doubling or tripling throughput. When you are trying to support global customers with short lead times from a limited number of distribution centers, that jump in throughput is often what makes same‑day shipping sustainable.

Warehouse automation is not free. NetSuite notes that high upfront costs, integration complexity, and the need for specialized skills are consistent challenges. However, the payoff is significant: higher throughput, fewer errors, better space utilization, and improved workplace safety. For automation components, where accuracy and packaging quality directly affect failure rates in the field, these benefits matter.

End-to-End Logistics Automation and Visibility

Beyond individual tools, supply chain automation uses technologies such as AI, IoT, and modern Transportation Management Systems to provide end‑to‑end visibility and control. Erbis notes that more than three‑quarters of organizations view big data, cloud computing, and AI as critical to managing supply chain complexity. Wisor reports that logistics companies using AI can automate roughly half of repetitive tasks while improving efficiency by about 30 to 40 percent.

On the ground, this looks like automated routing and scheduling that consider traffic and weather, predictive analytics for demand and stock levels, and IoT sensors providing real‑time data on shipment location and condition. Vecna Robotics describes how Autonomous Mobile Robots and integrated warehouse systems can run transport, picking, and storage around the clock, while IoT devices track temperature, humidity, and shock to protect sensitive goods.

Shipment tracking is a particular pain point for customers. Research summarized by Creative Logistics shows that over 90 percent of consumers want tracking, with roughly half wanting a general idea and about two‑fifths wanting real‑time updates, yet a third could not track their most recent delivery. In an industrial context, plant teams increasingly expect the same visibility. Integrating real‑time tracking, automated alerts, and customer portals into your delivery solution reduces support workload and prevents avoidable surprises at the dock.

Analytics and Continuous Improvement

The most mature organizations do not just automate; they measure. ShipERP’s analytics tools, Wisor’s performance analytics, and similar offerings from other vendors all emphasize tracking carrier performance, on‑time delivery rates, error rates, and logistics costs. Erbis recommends monitoring order cycle time, inventory turnover, and labor productivity to quantify return on automation.

From a systems‑integrator perspective, this is where you start to close the loop. You can see which carriers reliably deliver sensitive drives on time in certain corridors, which customs routes tend to generate clearance delays, and where warehouse picking errors are still creeping into shipments. That data feeds into better carrier contracts, refined routing rules, and targeted training.

Operating Model: Designing A Worldwide Delivery Playbook

Technology and legal knowledge are crucial, but they only work if your operating model is sound. Here is how experienced integrators and manufacturers are structuring their worldwide delivery playbooks, based on patterns echoed in sources such as Erbis, Workato, Xnova International, and university export guidelines.

Phase One: Map the End-to-End Flow

Serious export departments start by mapping the entire process, from order entry through final delivery and returns. Xnova International’s practical guide to export‑department automation breaks the export process into planning, packaging and labeling, ground transportation, port storage, loading, maritime transport, unloading, and final delivery. For automation components, you add configuration steps, pre‑shipment testing, and, often, on‑site commissioning.

Document what actually happens in each phase: which systems are involved, which documents are created, who touches the shipment, and where data is re‑keyed. This is not glamorous work, but without it, you cannot sensibly automate or manage risk.

Phase Two: Engineer Compliance Into the Process

Next, you embed compliance rules into that flow rather than treating them as an afterthought. That means making ECCN and HS classification part of the product lifecycle, not a last‑minute task in the shipping department. It means enforcing dangerous‑goods screening at the product and order level, not hoping someone notices the lithium battery icon on a datasheet.

University guidelines from Northwestern and South Alabama emphasize early export‑control reviews for controlled items and sensitive destinations, sometimes weeks before shipping. Xnova’s material underscores the same point in a commercial setting, recommending automated documentary checks and early‑warning systems for license expirations and regulatory changes. The lesson is consistent: if you engineer compliance into your workflow, you keep exports moving; if you bolt it on at the end, you invite delays.

Phase Three: Build A Technology Stack Around Reality

With your flow and compliance requirements clear, you select technology that matches reality. That usually means an ERP at the core, a WMS for inventory and warehouse processes, a TMS for transportation and carrier management, and specialized export‑automation and shipment‑automation tools for documentation, EEI filing, and tracking.

Workato and Jack Cooper both stress the importance of choosing tools that integrate easily with each other. APIs, pre‑built connectors, and cloud‑based platforms reduce the integration tax and avoid creating new silos. A tool might be excellent at route optimization in isolation, but if it cannot exchange data cleanly with your ERP, WMS, and export systems, it will create as many problems as it solves.

Phase Four: Choose the Right Partners and Service Levels

No matter how strong your internal stack is, you still rely on external partners: freight forwarders, express carriers, customs brokers, and local logistics firms. BIS guidance recommends assessing forwarders based on experience with your product types and destination countries, management oversight, and the maturity of their export compliance programs.

In practice, this means matching partners to lanes. For high‑risk or high‑value corridors, you want forwarders who understand automation hardware, export controls, and sanctions. For urgent spares, you rely on express integrators that can execute DDP deliveries and handle brokerage. For global sourcing of multi‑brand components, providers like Industrial Automation Co. and Automation Components, LLC can become strategic hubs.

The service‑level question is equally important. Not every shipment warrants air freight, but certain line‑down orders absolutely do. Shipping automation platforms are at their best when they encode this logic into rules, so front‑line teams choose from business‑friendly options rather than memorizing tariff books and service guides.

Phase Five: Audit, Measure, and Refine

Finally, you commit to continuous improvement. Xnova highlights internal audits of export departments using “360‑degree” visibility tools to detect non‑compliance before authorities do. Erbis and Wisor recommend monitoring key performance indicators such as error rates, on‑time delivery, and logistics costs to measure automation’s impact.

At a practical level, that means periodic reviews of export documentation quality, reclassification of problem SKUs, retraining for teams where errors cluster, and regular business reviews with your key carriers and forwarders. It also means adjusting warehouse layouts, packaging standards, and carrier portfolios as data reveals new bottlenecks or vulnerabilities.

Brief FAQ: Worldwide Delivery For Automation Components

How is shipping automation parts different from regular electronics? Automation parts often carry export-control classifications, embedded hazardous materials like lithium batteries, and dual‑use capabilities with potential military applications. Many also integrate into safety systems. That combination triggers stricter export rules, dangerous‑goods requirements, and higher risk if shipments are delayed or mishandled, compared with shipping generic consumer electronics.

When do I really need an export-control review? You should insist on export‑control review whenever you ship high‑performance drives, advanced PLCs (especially with strong encryption), specialized sensors, or any equipment destined for sensitive countries, defense applications, or research in high‑risk fields. University guidelines and BIS practice both favor the same rule of thumb: if you are unsure whether an item is EAR99 or controlled, or if you are not sure about the destination or end use, pause and classify before you ship.

Is shipping automation worth the investment for a mid-sized integrator or OEM? Yes, if you design it carefully. Even mid‑sized firms can benefit from multi‑carrier shipping tools, basic WMS capabilities, and partial process automation for labels, documents, and tracking. Evidence from providers like Wisor, Creative Logistics, and ShipERP shows that automation can cut manual work dramatically, reduce errors, and accelerate deliveries. The key is starting with high‑impact areas and integrating tools cleanly, rather than buying the most sophisticated system and forcing your processes to fit it.

Closing Thoughts

Worldwide delivery of automation components is not a side job for your warehouse manager. It is a core capability that protects your customers’ uptime and your own reputation. The organizations that get this right are not improvising shipments one at a time. They build compliant, automated, data‑driven delivery systems, supported by the right partners and grounded in a clear understanding of export rules and logistics realities. As a long‑time systems integrator, I can say this with confidence: the time and attention you invest in that delivery system will pay you back many times over in avoided downtime, fewer emergencies, and stronger, more durable customer relationships.

References

- https://www.bis.gov/freight-forward-guidance

- https://rso.iu.edu/export-control/international-shipping-exports.html

- https://exports.northwestern.edu/shipping-purchasing/international-shipping.html

- https://www.southalabama.edu/departments/research/compliance/export-control/resources/international-shipping-guidelines.pdf

- https://blog.shiperp.com/shipping-smarter-for-industrial-machines-components

- https://www.codept.de/blog/5-logistics-automation-strategies-you-should-be-aware-of

- https://creativelogistics.com/shipping-automation-how-it-works-benefits/

- https://www.jackcooper.com/logistics-automation-for-smarter-supply-chains/

- https://plcautomationgroup.com/blog/automation-parts-and-global-supply-chain

- https://www.rsa.global/blog/navigating-global-shipping-regulations-a-guide-for-businesses

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment