-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

International Shipping Solutions for DCS Modules: A Field Guide From the Integration Front Line

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

Why International Shipping Can Make or Break Your DCS Project

On paper, a distributed control system project is about controllers, I/O, HMIs, networks, and cybersecurity. In the field, the job often succeeds or fails on something more mundane: whether the right modules clear customs, arrive intact, and hit the site on the week you promised operations.

DCS projects are capital‑intensive and deeply embedded in plant operations. Industry guidance on DCS implementation highlights that costs span controllers, HMIs, redundant hardware, software licenses, and specialized engineering labor, with redundancy alone accounting for roughly forty percent of project cost in one refinery example. Those investments only create value once the hardware is on site, installed, and commissioned. A delayed or damaged pallet of I/O cards or network modules can push a cutover window, extend an outage, or force engineers to fly back later. That is how shipping errors quietly turn into seven‑figure consequences.

Logistics as a discipline views this through a broader lens. Standard logistics definitions emphasize planning, implementation, and control of the efficient, effective flow and storage of goods and related information from origin to consumption. Distribution focuses on the outbound side: transportation, warehousing, order processing, and delivery, so products reach the right customer, at the right place and time, in the right condition. Studies summarized in logistics handbooks regularly estimate that logistics activities consume on the order of 8 to 15 percent of national GDP or company sales. For a DCS vendor or systems integrator, that means logistics is not overhead; it is a strategic lever.

International shipping for DCS modules sits at the intersection of these worlds. It combines high‑value automation hardware, tight shutdown windows, cross‑border regulation, hazardous‑materials rules, and, increasingly, sustainability and data‑reporting obligations. The good news is that other high‑consequence domains, from national laboratories to diplomatic services and cross‑border e‑commerce, have already worked out practical patterns. If you treat your DCS module shipments with the same discipline, they become a manageable engineering problem instead of a recurring fire drill.

The Shipping Landscape for DCS Modules

Before choosing shipping solutions, it helps to align on terminology and constraints.

From a logistics perspective, DCS modules are part of an integrated outbound supply chain. They move from the manufacturer or integrator’s warehouse, often through one or more consolidation points, to a plant that may be across a border or on another continent. Logistics best‑practice literature stresses that these flows should be optimized as a system: transport mode and carrier choice, warehouse operations, inventory strategy, packaging, and information systems must work together to reach service‑level targets at the lowest total cost.

Cross‑border shipping is a specialized case. E‑commerce sources define cross‑border shipping as fulfilling orders that cross at least one international border, requiring customs clearance, duty and tax handling, and coordination with international or regional carriers beyond standard domestic shipping. The business case is clear: done well, it opens new markets and protects margins; done poorly, it produces surprise fees, customs holds, and a poor customer experience. Translating that to industrial automation, your “customer” is the plant operations team and your “surprise fee” is an extra week of downtime.

On the control‑system side, DCS implementation guidance reminds us that these projects are lifecycle initiatives. A modern DCS should support phased rollouts, integration with legacy systems, and long‑term maintainability and cybersecurity. That lifecycle view must apply to logistics as well. Module shipments continue for years: spares, upgrades, and expansions. Designing a robust shipping framework early pays off across the entire DCS life.

Risk Categories: Hazard, Weight, and Configuration

A useful way to structure shipping decisions for DCS modules is to borrow a framework from Washington State University’s Dynamic Compression Sector shipping instructions, which differentiate shipments by hazard status, weight, and inbound versus outbound direction. Although those rules were written for scientific hardware, the principles travel well.

First, distinguish hazardous from non‑hazardous materials. Hazardous materials are defined, in U.S. practice, as substances classified as hazardous by the Department of Transportation or the International Air Transport Association. Examples in the experimental context include high explosives and flammable materials. In that environment, nonexempt hazardous materials cannot be brought in personal vehicles at all; they must go through formal hazardous‑materials receiving and shipping channels with documented approvals and safety data sheets. For most DCS modules, the hardware itself is non‑hazardous, but you may have associated hazardous items such as chemicals, certain batteries, or test materials. Treat those as a separate logistics stream with their own approvals, not as afterthoughts in the same crate as the controllers.

Second, consider shipment weight and physical size. The Dynamic Compression Sector distinguishes non‑hazardous shipments at or below 49 lb from those at 50 lb or above. Lighter shipments can be shipped normally or even hand‑carried; heavy or oversize shipments require rigging services, advance scheduling, and dedicated cost codes. The same pattern applies on a DCS project. A carton of spare I/O modules is one problem; a loaded cabinet or marshalling rack on a skid can weigh several hundred pounds and demand specialized handling at both origin and destination.

Third, inbound versus outbound flows behave differently. Inbound shipments to a lab or plant may require pre‑approval, detailed manifests, and clear timelines. Outbound shipments, such as returning failed modules or sending upgraded hardware back to a central facility, may trigger different documentation and inspection rules. At the Dynamic Compression Sector, heavy outbound shipments must be fully packed but left unsealed for inspection, with contents, values, and any hazardous components clearly documented. If you mirror that discipline in your DCS supply chain, you will reduce surprises when equipment crosses borders in both directions.

Hazardous Materials, Export Control, and Sensitive Technology

When DCS modules move internationally, physical hazard is only part of the risk. Export‑control and end‑use considerations can be just as important.

University export‑control offices, such as the one at the University of South Alabama, typically guide researchers to ask four screening questions before shipping anything: what is being shipped, where is it going, who is the end user, and why or how will it be used. They define an export as the transfer of items, software, or technical data to a foreign country or foreign national, and a deemed export as the release of controlled technical information to a foreign person inside the United States. Controlled items are those regulated under regimes such as the Export Administration Regulations or the International Traffic in Arms Regulations.

Those same questions apply directly to DCS modules. Advanced controllers, high‑performance computing hardware, certain networking gear, and specialized sensors can fall into higher‑risk categories in export‑control lists, especially if destined for sensitive sectors or embargoed countries. Generic guidance emphasizes that items related to aerospace, navigation, telecommunications, strong encryption, or advanced sensing often merit additional review. While the specific classification of any given DCS module depends on its technical parameters, you should assume that export‑control review is necessary whenever modules cross borders.

Destination‑control requirements add a further compliance layer. The U.S. Department of Commerce explains that a Destination Control Statement is required for certain exports. It declares the country of ultimate destination and reinforces that the goods are destined only for that country. Best practice is to integrate the required statement language into your standard commercial invoice and shipping document templates, ensuring the stated destination matches all licensing and internal records. That is particularly relevant when DCS modules transit through intermediate hubs or integrator facilities; the final intended country must remain clear and consistent.

Hazardous materials layer on top of this export‑control picture. The Dynamic Compression Sector’s rules show how strict this can become in a high‑risk environment: hazardous materials must be documented in safety forms, accompanied by Safety Data Sheets, shipped to dedicated hazardous‑materials receiving facilities, and never moved in personal vehicles. Explosive materials require extra approvals and inspections before both inbound and outbound shipments. While most DCS hardware is not explosive, if your shipment includes hazardous substances of any kind, assume that your shipping solution must meet similar expectations: clearly identify the material, route it through proper channels, and synchronize safety approvals with export‑control reviews.

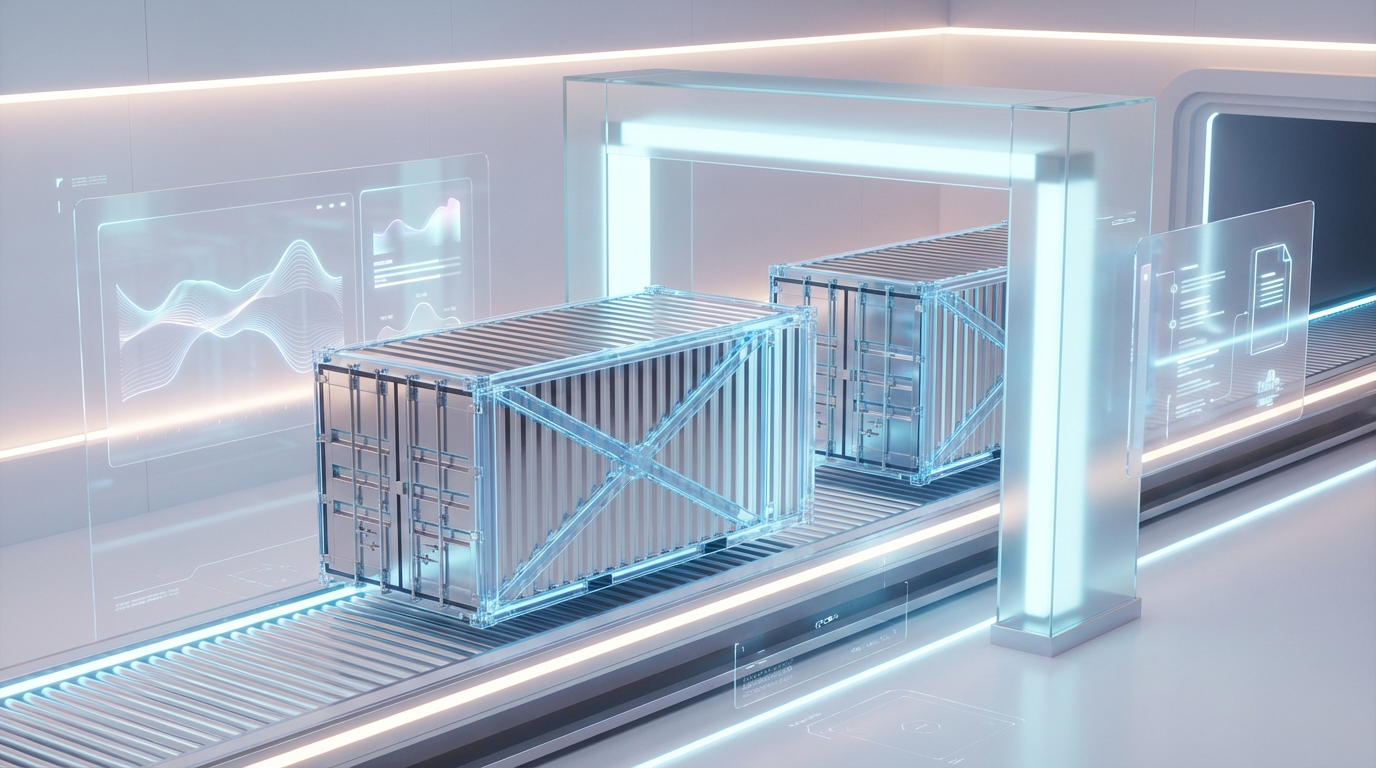

Packaging Engineering: Designing Shipments That Survive the Journey

Even with perfect paperwork, a DCS module that arrives damaged is still a failure. Here, it is worth borrowing from two sets of demanding packaging standards: the U.S. diplomatic pouch system and national‑lab shipping practices.

The diplomatic‑pouch rules in the U.S. Foreign Affairs Manual require that items survive rough handling, including a drop from about 10 ft, with no loss of contents. They specify that fragile contents must be cushioned, powders and allowed liquids sealed in plastic bags, items immobilized inside the container, and box strength matched to weight. For unclassified pouches, guidance links packaging material to maximum weight: simple paperboard cartons up to about 10 lb, metal‑stayed paperboard up to about 20 lb, and solid or corrugated fiberboard of various grades up to 20, 40, 65, or 70 lb, depending on the grade.

These are not DCS‑specific rules, but they illustrate an engineering mindset that maps well to industrial electronics. Rather than treating packaging as a cardboard afterthought, treat it as a mechanical design problem: what drop, crush, and vibration environment will the crate see between factory and control room, and what structure is required to keep boards, baseplates, and terminals intact and uncontaminated?

Guidance from the Dynamic Compression Sector also underscores the value of redundancy and segregation. Users there are advised to fabricate extra experimental targets, sending more units than planned experiments, and to secure delicate probes and fiber bundles separately from heavy mounts. Translated to DCS logistics, that suggests shipping a modest number of critical spares in separate, smaller packages, and separating especially fragile or high‑value modules from heavier cabinets or hardware. The probability that at least one of them arrives in working condition goes up dramatically when they are not all exposed to the same handling risk.

A practical way to combine these ideas is to standardize a small set of packaging archetypes for DCS hardware, each with a defined weight envelope and internal protection strategy, and then stick to them across projects. That dovetails well with modern warehouse‑management systems, which the logistics literature recommends for giving you consistent data on inventory, packaging, and handling.

Cross‑Border Shipping Models That Actually Work for DCS Hardware

When your DCS modules cross a land border, you face the same structural issues that high‑volume freight and e‑commerce shippers have been solving for years: customs complexity, capacity constraints, and variable carrier performance.

Trade and logistics providers such as Averitt and GlobalFreightEx describe cross‑border shipping as high opportunity and high risk. Regulatory regimes differ by country for classification, valuation, country of origin, and restricted items. Incomplete or inaccurate documentation can trigger fines, holds, or even seizure of goods. Language barriers between shippers, customs brokers, and carriers slow problem resolution. Capacity swings, driver shortages, weather, and infrastructure bottlenecks pressure reliability.

A few proven patterns from North American cross‑border practice translate well to DCS modules.

First, recognize the centrality of trucking for many land borders. Supply‑chain analysis cited in industry articles notes that in one recent year nearly seventy percent of freight crossing the U.S.–Mexico border moved by truck, highlighting how critical truck capacity and carrier choice are. For DCS modules moving between neighboring countries, full truckload is often efficient when you can consolidate multiple cabinets or racks into a single move. For non‑urgent or smaller volumes, less‑than‑truckload, potentially consolidated near the border, can control cost.

Second, use near‑border facilities and transloading strategically. Practitioners describe how warehouses near crossings shorten the distance between distribution centers and the border, allowing more daily truck trips even under congestion. They can serve as hubs to deconsolidate, reconfigure, and reload freight into bonded carriers for the crossing, while keeping duties and customs processes aligned with your route. For DCS projects, staging modules at a border‑proximate warehouse can give you a buffer: you can clear customs and then deliver to the plant on a precise shutdown schedule.

Third, choose carriers with the right security credentials. Programs such as the Customs‑Trade Partnership Against Terrorism and the Free and Secure Trade initiative offer lower risk scores, fewer inspections, and faster processing for approved shippers, carriers, and drivers. Cross‑border articles emphasize that C‑TPAT‑certified carriers and FAST lanes materially reduce border uncertainty. For high‑value DCS hardware, that reliability is often worth more than shaving a few dollars off the freight bill.

Fourth, match the shipping model to the product and risk profile. Trade sources describe transloading, where freight is transferred between carriers at a border‑area facility, as a cost‑effective strategy for many goods, especially when you can consolidate under‑utilized trucks. Door‑to‑door service, in which one carrier handles the move end to end, is often recommended for time‑critical or heavily regulated products such as pharmaceuticals. For DCS modules, which are both high‑value and schedule‑critical, it is often prudent to favor door‑to‑door for final system cabinets and use more cost‑optimized modes for spare parts and non‑critical items.

Underpinning all this is technology. Cross‑border best‑practice articles advocate transportation‑management systems that provide real‑time load visibility, route optimization, and integrated electronic documentation, such as advance manifests that customs can screen before the truck arrives. Because deploying a sophisticated TMS can be complex, several sources point to working with third‑party logistics providers who already operate platforms tuned to cross‑border operations, rather than building from scratch.

Documentation, Customs Data, and Landed Cost Transparency

Documentation quality is the single strongest lever you have over customs risk and delay.

Multiple cross‑border shipping sources converge on the same point: customs problems usually trace back to poor paperwork. Best‑practice lists from Averitt, GlobalFreightEx, and a range of international‑shipping experts stress accurate commercial invoices, detailed packing lists, correct classification and valuation, clear country‑of‑origin declarations, and certificates of origin where required. University export‑control guidance adds end‑use and end‑user statements and references to export‑license numbers or license exceptions when applicable. Trade‑compliance overviews note that documentation must also align with any sanctions or restricted‑party screening you conduct.

E‑commerce‑focused guidance on cross‑border shipping, which is surprisingly relevant, recommends standardizing and digitizing customs data. That means maintaining reliable product descriptions, harmonized tariff codes, and country‑of‑origin details in your core systems, not reconstructing them on the fly for each shipment. Integrated warehouse‑management and transport‑management systems, advocated in logistics handbooks, provide exactly this: a single data spine for orders and shipments.

Landed‑cost transparency is another lesson worth importing from retail to automation. Cross‑border e‑commerce sources warn against “surprise duties” at delivery and suggest calculating and disclosing duties, taxes, and any brokerage fees up front. They recommend explicitly choosing between Delivered Duty Paid and Delivered At Place terms, rather than treating them as side notes, so that the buyer knows whether they must pay duties and taxes separately.

For DCS modules, the same principle applies in a commercial rather than consumer context. If your quote to a plant or EPC contractor assumes Delivered Duty Paid, you are responsible for duties, taxes, and most logistics issues. If you quote Delivered At Place, the buyer must handle import clearance and final duties. Aligning these assumptions explicitly avoids unpleasant conversations once the crates are sitting in a customs warehouse.

A simple conceptual comparison can help project teams clarify responsibilities:

| Term | Duties and taxes | Import customs clearance | Primary risk for border delays |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delivered Duty Paid | Seller pays and arranges | Seller is responsible | Mostly on seller and their logistics partners |

| Delivered At Place | Buyer pays and arranges | Buyer is responsible | Mostly on buyer and their brokers/carriers |

These patterns are described in international‑shipping best‑practice material and are as relevant for control hardware as they are for consumer goods. The implementation detail is different, but the allocation of responsibility is the same.

Sustainability and Ocean Shipping: The Other DCS You Must Know

When DCS modules move by sea, another “DCS” enters the picture: the International Maritime Organization’s Data Collection System for fuel oil consumption. Under a resolution adopted in 2016, ships of 5,000 gross tonnage and above, which account for roughly eighty‑five percent of carbon dioxide emissions from international shipping, must collect and report annual fuel consumption and operational data. Since 2023, that data feeds into each ship’s operational carbon‑intensity rating.

While this requirement falls on the ship operator, not the cargo owner, it has practical implications for DCS module shipments. Carriers must maintain accurate records and adhere to reporting timelines: ships submit aggregated data to their flag State, which verifies and forwards it to the IMO by mid‑year. Flag States then issue Declarations of Compliance.

The system is backed by detailed implementation guidelines and integrated into the IMO’s information systems.

For a systems integrator or project owner, this influences carrier choice and contract structure. Carriers that manage compliance well are less likely to face operational constraints or penalties that could ripple into schedule risk. It also intersects with corporate sustainability and ESG goals. When you are modernizing a DCS partly to improve energy efficiency and data transparency in a plant, it is consistent to prefer shipping partners whose operations are aligned with global greenhouse‑gas‑reduction frameworks. At minimum, you should expect your freight forwarder or carrier to understand and comply with IMO’s Data Collection System and related carbon‑intensity regulations.

Integrating Shipping into DCS Modernization and Implementation Programs

DCS modernization guidance emphasizes three big themes: lifecycle planning, staged migration, and cybersecurity. Shipping decisions should be wrapped into that same framework rather than left as isolated purchasing tasks.

Lifecycle planning means aligning hardware refresh cycles, plant‑unit lifetimes, and logistics capabilities. Typical asset‑life guidelines for process control equipment indicate long lifetimes for wiring and field panels, shorter for controllers, and even shorter for operator workstations. This naturally leads to staged upgrades rather than one‑shot replacements. If your logistics model assumes a one‑time, massive shipment and does not account for a steady stream of upgrades and spares for the next decade, it is misaligned with the control strategy.

Staged migration is about risk and downtime control. DCS modernization articles recommend phased or unit‑by‑unit migration and discourage big‑bang cutovers, especially when integrating with legacy PLCs and proprietary protocols. That same philosophy should guide shipping. Instead of a single, monolithic international move that must be perfect, structure shipments so that each phase’s hardware can be delivered, inspected, and staged ahead of its cutover. The national‑lab shipping example of requiring heavy outbound packages to be fully packed by the end of a run, or by noon the next day, reflects this sensitivity to scheduling.

Cybersecurity, while often discussed in terms of network design and patching, interacts with logistics as well. Modern DCS guidance calls for compliance with standards such as NERC‑CIP and IEC 62443 and for layered defenses including firewalls and continuous monitoring. A less obvious but important element is hardware chain of custody. Knowing exactly where your controllers, network switches, and security appliances have been, and through whose hands, matters when you later attest to their integrity. Working with reputable carriers, maintaining accurate shipment tracking, and avoiding undocumented intermediate stops all help preserve that chain.

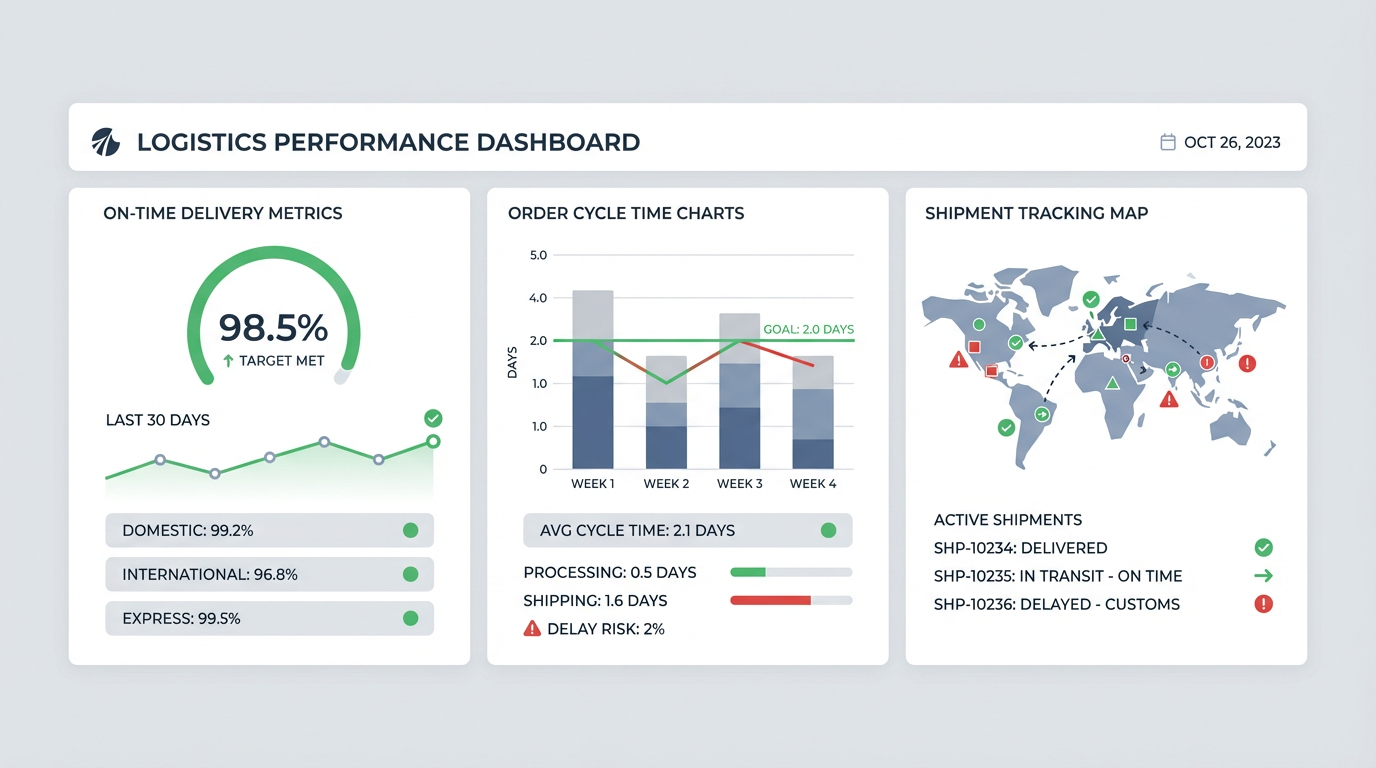

Logistics and distribution management literature recommends using key performance indicators like on‑time, in‑full delivery and order‑cycle time to monitor and improve performance. Build those KPIs into your DCS program dashboards.

If a plant’s cutover window is at risk, you should see that coming in the logistics data weeks earlier, not on the Friday before a shutdown.

A Practical Shipping Playbook for a Cross‑Border DCS Module Upgrade

To make these principles concrete, consider a cross‑border DCS modernization for a process unit in another country.

Early in basic design, you treat logistics as a workstream. You classify the modules and cabinets from an export‑control perspective, identifying any hardware that may fall into higher‑risk categories. You engage your organization’s export‑control office to determine whether licenses or license exceptions are needed and ensure that the required Destination Control Statement language will appear on all shipping documents.

In parallel, you segment the bill of materials into logical shipments. Final system cabinets and essential network infrastructure are grouped into a door‑to‑door shipment with a carrier that is strong in cross‑border work and holds security credentials such as C‑TPAT certification. Spare modules and non‑critical items are planned for consolidated less‑than‑truckload shipments to manage cost.

You work with a third‑party logistics provider that operates a transportation‑management system capable of handling cross‑border documentation, including electronic manifests and standardized customs data. Together, you standardize item descriptions, harmonized tariff codes, and country‑of‑origin information for each hardware line. You decide, explicitly, whether your commercial terms mean you as the integrator will handle duties and taxes (the equivalent of a Delivered Duty Paid posture) or whether the plant owner will take that responsibility (similar to Delivered At Place), and you document that in contracts and internal instructions.

On the physical side, you borrow from diplomatic‑pouch packaging rules and national‑lab practice. Heavy cabinets are mounted on robust skids and crated in fiberboard or wood structures designed to withstand rough handling and drops. Fragile modules are packed separately with internal cushioning and immobilization. For particularly critical items, you send a small number in a separate, lighter package so that a single incident cannot wipe out all availability.

Because cross‑border practitioners emphasize the value of near‑border warehouses, you arrange for the main shipment to pass through a border‑proximate facility operated by your logistics partner. There, shipments are checked, transloaded if needed, and staged so that delivery to the plant can align precisely with the outage schedule. Throughout, your TMS provides real‑time tracking and alerts, so project management can see when hardware has cleared customs and is en route.

Finally, you plan for returns and replacements. Cross‑border e‑commerce guidance underscores the importance of a simple returns process. In an industrial context, that means defining in advance how failed modules will be shipped back across the border, who will handle customs for returns, and how export‑control and hazardous‑materials rules apply to defective hardware. You incorporate those flows into your logistics procedures rather than waiting for the first failure to discover the gaps.

Brief FAQ

Q: Are DCS modules themselves considered hazardous materials for shipping purposes? A: In most cases, DCS modules are treated as non‑hazardous electronics. However, guidance from hazardous‑materials shipping environments shows that any associated hazardous substances, such as chemicals or energetic materials, must be handled under strict rules, with safety documentation and specialized receiving channels. The safest approach is to treat obvious hazardous items as a separate logistics stream and follow hazardous‑materials and export‑control procedures for them.

Q: How early should I involve export‑control and customs experts in a DCS project? A: Export‑control offices and customs specialists recommend early engagement, at the planning stage rather than just before shipping. University shipment‑preparation guidance emphasizes allowing sufficient lead time for export‑license determinations, classification, and documentation. For a DCS modernization or greenfield project, that means involving these experts during basic design or procurement, not after cabinets are already on the factory floor.

Q: What is the most common root cause of customs delays for cross‑border DCS shipments? A: Cross‑border shipping analyses consistently point to documentation errors and omissions as the primary culprits, rather than exotic regulatory issues. Incomplete invoices, inconsistent product descriptions, incorrect classification codes, or missing country‑of‑origin information frequently lead to holds, fines, or return to sender. Standardizing and digitizing customs data, and integrating that into your warehouse‑management and transport‑management systems, is the most effective remedy.

As a systems integrator who aims to be a reliable project partner, I treat international shipping for DCS modules as part of the control strategy, not as an afterthought. When you fold export‑control, hazardous‑materials discipline, packaging engineering, and cross‑border logistics into your project from day one, the hardware simply shows up when and where it is needed—and the plant’s operators remember you for a smooth start, not a delayed one.

References

- https://techport.nasa.gov/strategy

- https://www.trade.gov/destination-control-statement-dcs

- https://dcs-aps.wsu.edu/shipping-instructions/

- http://fam.state.gov/FAM/14FAM/14FAM0720.html

- https://www.cdse.edu/Portals/124/Documents/student-guides/IF107-guide.pdf

- https://www.southalabama.edu/departments/research/compliance/export-control/resources/shipment-preparation-items-to-consider.pdf

- https://www.imo.org/en/ourwork/environment/pages/data-collection-system.aspx

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269198167_Transportation_Considerations_in_Module_Design

- https://scg-mmh.s3.amazonaws.com/pdfs/lucas_wp_eliminating_dc_travel_with_ai_020824.pdf

- https://www.averitt.com/blog/cross-border-shipping

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment