-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Customs Clearance for Automation Equipment: Import Process Guide

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

When your new robot cell or motion platform sits on a dock instead of on the plant floor, nobody cares that the wiring diagrams are perfect. The project is late, production is waiting, and the critical path now runs straight through customs. As a systems integrator, I have seen more schedule risk from customs missteps than from any PLC program, which is why I treat customs clearance as a project deliverable, not an afterthought.

This guide walks through how customs clearance actually works for automation and industrial control hardware, how duties and fees are calculated, where projects usually get burned, and how to use brokers and modern automation tools to stay ahead of the process. The focus is on importing into the United States, but the principles apply broadly to other markets.

What Customs Clearance Really Is

Customs clearance is the process by which government authorities authorize goods to enter or leave a country. Sources like Welke, Invensis, and UPS describe it in similar terms: it is a formal sequence where officials verify the nature, quantity, value, and origin of the goods; check compliance with trade, safety, and security rules; assess duties and taxes; and then decide whether to release, inspect, or hold the shipment.

In the United States, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is the primary agency. A customs entry is filed, typically electronically, with key documents such as the commercial invoice, packing list, and bill of lading or air waybill. UPS notes that for goods intended for domestic use, the standard entry type is a consumption entry, commonly submitted on CBP Form 3461 and followed by an entry summary on CBP Form 7501.

Dimerco and ATS emphasize the same basic steps: prepare documents, transmit an electronic declaration, have duties and fees assessed, undergo possible inspection, pay what is due, and then receive release. If documentation is wrong or incomplete, the process stops and your equipment does not move.

For automation projects, this is not just a legal formality. Customs clearance acts as the gate between your capital spend and your production schedule. Treat it with the same rigor as safety validation or FAT, and your chances of staying on schedule rise dramatically.

Why Automation Equipment Is a Special Case

Most guidance on customs clearance talks about “machinery” and “heavy equipment.” Industrial automation hardware falls squarely in that category but brings some specific twists.

Freightclear’s explanation of construction machinery imports highlights that complex machines must meet local safety and emissions standards and may fall under multiple regulatory agencies. In the U.S., that can include environmental regulators like the Environmental Protection Agency, workplace safety agencies such as OSHA, and sector‑specific bodies depending on the use-case. Freightos and Welke remind importers that a variety of partner government agencies, including organizations such as the FDA or USDA, regulate certain product categories and must clear their portion before CBP can release the goods.

Automation equipment is typically high value, often customized, and difficult to replace quickly. One misclassified control cabinet or misdocumented motion system can tie up six figures of hardware and weeks of schedule. At the same time, smaller replacement parts and subassemblies may fall under de minimis thresholds or simplified entry types, so understanding how value, classification, and entry type interact is crucial.

Core Concepts Every Automation Team Must Understand

Importer of Record and Shared Responsibility

Freightclear defines the importer of record as the person or entity responsible for ensuring imported machinery complies with all applicable laws and regulations. CBP guidance on basic importing and exporting is clear that customs authorities and the trade community share compliance responsibilities, but the importer of record remains ultimately accountable for accurate declarations and payment of duties and taxes.

Hiring a customs broker does not transfer responsibility. Dimerco and CBP both stress that the importer must understand the basics, even when outsourcing the day‑to‑day filings.

HS Codes and Tariff Classification

Every product you import must be assigned a Harmonized System (HS) code. Dimerco explains that there are roughly tens of thousands of HS codes globally, identifying not just broad categories such as shirts or machinery, but very specific variants, each potentially carrying different duties and regulatory requirements.

For U.S. imports, the first six digits form the international HS code; the full ten‑digit number is the Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) number. Freightos, SaraPSL, and One Union Solutions all highlight that correct classification is one of the most critical steps in customs clearance. Misclassification can alter duty rates, trigger extra inspections, and lead to penalties.

For automation equipment, classification must correctly reflect what the equipment actually does and how it is used, not just how a supplier markets it.

A misclassified robot, drive, or machine module could shift you into the wrong duty band or under the jurisdiction of an entirely different regulator.

Customs Valuation and Duty Types

Freightos describes customs duties as taxes on imported goods designed to protect domestic markets, generate revenue, and monitor trade. The duty calculation depends primarily on the HS or HTS code and the declared value of the goods.

Several types of charges can apply:

Customs duties are the baseline tariff tied to classification and origin. Freightos notes that additional U.S. tariffs such as USTR Section 301 duties apply to many goods from China, ranging from about 7.5 percent to 25 percent of value.

Anti‑dumping (AD) and countervailing (CVD) duties, described in detail by Freightos, are layered on when investigations by the U.S. Department of Commerce and the International Trade Commission conclude that foreign producers are dumping goods below normal value or benefiting from unfair subsidies. These apply only to specific commodities identified in those investigations but can be significant.

Dimerco’s experts also point to other U.S. fees such as the Merchandise Processing Fee, calculated at 0.3464 percent of declared value with a minimum of $27.75 and a maximum of $538.40 as of late 2021, and the Harbor Maintenance Fee on ocean shipments at 0.125 percent of declared value.

When you are building a landed‑cost model for a new automation platform, ignoring these layers is a recipe for blown budgets. Treat the HS code and valuation as core engineering inputs, not accounting afterthoughts.

Entry Types, De Minimis, and Customs Bonds

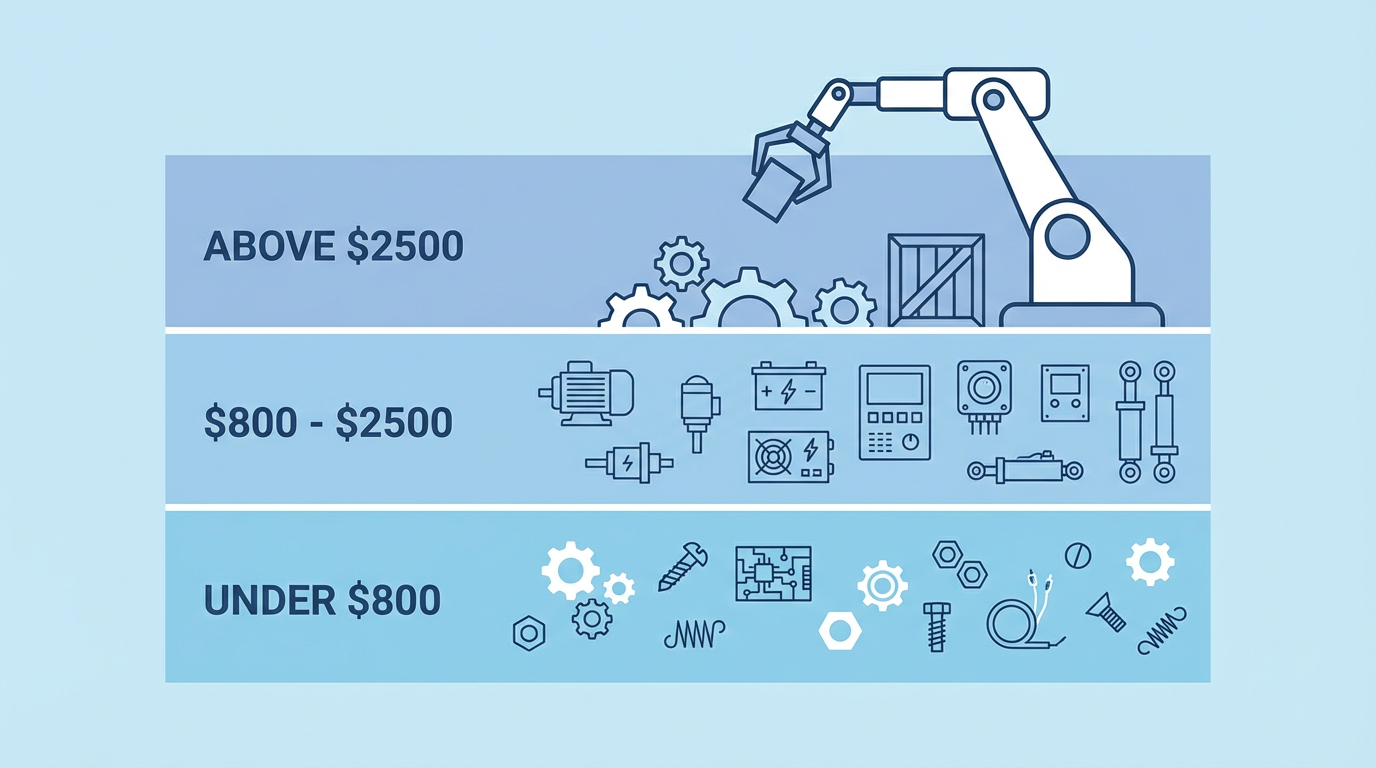

UPS and ATS outline multiple U.S. entry types, including formal and informal consumption entries, warehouse entries, temporary import bonds, Section 321 entries, and foreign trade zones. Freightos adds practical thresholds:

Shipments under $800 can often enter under the Section 321 de minimis rule, without duties or a customs bond.

Shipments between $800 and $2,500 typically qualify as informal entries with a somewhat simpler clearance process, although a bond may still be required depending on the goods.

Shipments above $2,500 usually require a formal entry, a customs bond, and full compliance with all standard procedures.

Automation hardware is often well above the formal entry threshold, but spare parts and small tools may fall into de minimis or informal territory. Understanding which shipments can be structured that way can cut cost and paperwork without compromising compliance.

ATS explains that no shipment can enter the U.S. without a customs bond. Importers can purchase a single‑entry bond for one‑off shipments or a continuous bond that covers a full year of imports. For ongoing automation projects or multi‑site rollouts, a continuous bond is usually more efficient.

Step‑by‑Step Import Process for Automation Equipment

Different sources describe the customs process with slightly different step counts, but they describe the same core flow. Combining guidance from ATS, Dimerco, TriLink, Freightos, and CBP, the import path for automation hardware typically looks like this.

Pre‑Arrival Planning

The most effective customs work happens before the equipment ever leaves the supplier. Ship4wd, SaraPSL, and Dimerco all stress the importance of pre‑arrival clearance. That means confirming HS codes, determining the correct entry type, securing any regulatory approvals, and gathering all documentation early.

For ocean shipments into the U.S., CBP requires the Importer Security Filing (the “10+2” rule) to be submitted at least 24 hours before cargo is loaded on the vessel, as described in CBP’s tips for new importers. Ship4wd emphasizes that late or missing security filings are a common cause of penalties and holds.

Your goal should be exactly what Dimerco recommends: have the entry ready and, ideally, cleared before the vessel or aircraft arrives, so your cargo can move to the plant or integration site with minimal dwell time.

Document Preparation and Data Quality

Document quality is where most projects stumble. Welke, TriLink, Inbound Logistics, Freightos, and Dimerco all highlight incomplete or inaccurate paperwork as the leading cause of customs delays.

The core documents are remarkably consistent worldwide:

The commercial invoice, provided by your vendor, is the basis for valuation and classification. Freightos lays out the essential content: complete exporter, seller, consignee, and buyer details; invoice number and shipment date; country of origin; detailed description of the goods including composition and intended use; quantities; net and gross weights; transaction value and total value including freight, insurance, and packing as required; currency; Incoterms; HS or HTS codes; shipping information; tax identification for the U.S. buyer; ports; all charges; and a signed declaration from the exporter. It must be in English or accompanied by an English translation.

The packing list details what is physically in each crate or container. ATS notes that CBP uses it together with the invoice to understand the shipment and verify physical inspections.

The bill of lading or air waybill, described by ATS, Freightos, and Inbound Logistics, is both a receipt from the carrier and a transport contract. It also proves the right to make entry. It must be presented as part of the entry package.

The certificate of origin, discussed by Welke and others, proves the manufacturing country and is critical for applying any preferential tariff treatments under trade agreements.

Entry forms and electronic declarations, such as CBP Forms 3461 and 7501 in the U.S., are filed through systems like the Automated Commercial Environment, often via the Automated Broker Interface. ATS notes that all entry documents must be filed within 15 days of arrival, while the entry summary is typically due within ten working days of release.

Depending on what your automation equipment does, additional documents may be required: inspection certificates, safety or emissions certifications, or approvals from specific agencies. Freightos points to agencies such as the FDA, USDA, and CPSC for various goods; Freightclear highlights agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency and OSHA for machinery in particular use cases. The lesson is that you must understand whether your commodity triggers partner‑agency rules and secure those documents before shipping.

Duties, Taxes, and Payment

TriLink’s four‑step customs model assigns an entire step to duty and tax assessment. Once your entry is lodged, customs calculates the amounts due based on classification, valuation, origin, and any special duties such as Section 301 or AD/CVD.

TriLink reports that payment is the stage where shipments are most often held, because goods usually will not be released until all assessed charges are paid. Dimerco’s brokerage experts add that inspection fees, regulator fees, and bond costs can add to the total.

Delivery terms matter here. Inbound Logistics and TriLink contrast Delivered Duty Unpaid, where the importer or end customer must handle payment at arrival, with Delivered Duty Paid, where the seller has calculated and pre‑paid duties and taxes. For project work, DDP has more front‑end effort but avoids small plants or end users being surprised with large customs bills and delays at the last mile.

Inspection, Release, and Delivery

Once documents are accepted and duties are secured, customs authorities decide whether to release the shipment outright, route it for inspection, or grant conditional release. Welke notes that inspections and holds can add roughly one to three days in typical cases, and sometimes more, depending on risk level and product type.

ATS indicates that when everything is handled correctly, clearance from arrival to release often takes roughly 24 to 72 hours. Dimerco’s experience is similar: entries transmitted early and correctly often clear in less than a day, but incomplete paperwork or regulatory complications can push that out significantly.

For automation projects, the risk is not only delay but also misalignment with site resources. If your robots, drives, and panels are stuck at the port during a narrow crane window or contractor mobilization, the costs escalate quickly. Aligning customs timelines with project milestones is as important as aligning fabrication and installation.

Key Documents for Automation Equipment Imports

The volume of paperwork can seem overwhelming, but the set of core documents is finite. Drawing on guidance from Freightos, Welke, ATS, Dimerco, and Freightclear, the essentials for automation equipment can be summarized as follows.

| Document | Who Primarily Issues It | Why It Matters for Automation Equipment |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial invoice | Equipment supplier or exporter | Defines value, detailed description, origin, and HS/HTS codes; forms the basis for duty calculation and admissibility decisions. |

| Packing list | Supplier or packer | Allows customs and carriers to verify what is in each crate or container; critical for complex multi‑crate automation skids and panels. |

| Bill of lading or air waybill | Ocean, air, truck, or rail carrier | Evidence of shipment and right to make entry; ties cargo to the party responsible for customs. |

| Certificate of origin | Manufacturer, chamber of commerce, or authorized body | Enables preferential duty treatment under trade agreements and confirms origin for country‑specific restrictions. |

| Entry forms and electronic declarations | Customs broker or importer | Transmit the legal customs entry, including CBP Forms 3461 and 7501 for U.S. imports, through systems like ACE. |

| Customs bond | Surety company via broker or importer | Guarantees payment of duties, taxes, and fees; required for most formal entries, especially for high‑value machinery. |

| Security filings (for example, ISF 10+2) | Importer or their agent | Provide advance cargo data so customs can assess security risk before loading or arrival. |

| Regulatory permits and certificates | Manufacturers, testing labs, or regulators | Cover safety, emissions, environmental, or sector‑specific rules when the automation equipment falls under a partner agency’s jurisdiction. |

For every automation project, I recommend treating the commercial invoice and HS classification as controlled documents, reviewed by someone who understands both the technical function of the equipment and the regulatory implications, rather than leaving them solely to procurement or finance.

Costs: Duties, Fees, and Landed Cost for Automation Gear

From a project perspective, the customs line in the budget is rarely just “duty.” Drawing together insights from Freightos, Dimerco, TriLink, and Welke, your landed cost for imported automation equipment may include several components.

Baseline customs duties are the standard tariffs derived from your HS or HTS classification and the country of origin. Section 301 duties, where applicable, are layered on top and can add anywhere from around 7.5 percent to 25 percent for affected products from countries such as China.

In some sectors, anti‑dumping and countervailing duties apply to specific categories of goods after formal investigations. Freightos emphasizes that these apply only to defined commodity groups but can dramatically change economics when they do.

In the U.S., Dimerco highlights the Merchandise Processing Fee at 0.3464 percent of declared value within defined minimum and maximum amounts, plus the Harbor Maintenance Fee on ocean shipments at 0.125 percent. These are modest compared with some tariffs but material on high‑value robots and production lines.

On top of government charges come customs brokerage fees, freight forwarder charges related to customs, terminal handling, potential storage and demurrage if there are delays, and inspection station costs if CBP or another agency moves your cargo for examination. CBP’s own importer guidance notes that exam‑related charges at centralized inspection stations can easily reach several hundred dollars per shipment and are the importer’s responsibility.

From a systems integrator’s standpoint, this means the customs model belongs in your early business case. It should be reviewed alongside power, utilities, and installation costs, not tacked on after the equipment is already ordered.

Why Brokers and Forwarders Belong on Your Project Team

Multiple sources encourage using licensed customs brokers, especially for small and mid‑sized importers or those handling complex, high‑value or regulated goods.

Dimerco describes the broker’s role as navigating entry procedures, admissibility requirements, HS classification, valuation, and agency rules, while preparing and submitting all required documents. Clearit USA adds that brokers help avoid mistakes, speed processing, and save time and money, especially for first‑time or low‑volume importers.

Welke explains that brokers are licensed by national authorities and can be particularly valuable when entering new countries, handling high‑value machinery, or dealing with high shipment volumes. They note that pricing models often range from flat fees around tens to a couple hundred dollars per shipment to a small percentage of declared value.

However, CBP’s tips for new importers emphasize that even when a broker is involved, the importer of record is still legally responsible. That means your project team must still understand what is being filed and why.

For automation projects, the most effective pattern often pairs a broker integrated with the freight forwarder, as suggested by Dimerco, so transportation, documentation, and customs filings flow through one coordinated channel. You get fewer hand‑offs, fewer opportunities for miscommunication, and better pre‑arrival planning.

How Automation and AI Are Transforming Customs Compliance

It is fitting that teams importing automation equipment can now rely on automation in customs itself. Several sources focus on how digital tools, AI, and connected platforms streamline compliance.

Strixsmart describes how CBP’s ACE 2.0 platform and similar systems use machine learning to process customs entries faster, cut average processing time by roughly 40 percent, and raise the rate at which inspections actually uncover violations. They point out that AI models scan for anomalies in pricing, classification, and supplier risk before goods reach the port.

Private‑sector tools, according to Strixsmart, now offer automated classification that analyzes product descriptions, specifications, and other data and can suggest HS codes with accuracy around 95 percent. Intelligent document processing uses optical character recognition and natural language processing to extract data from invoices, packing lists, certificates, and emails in many languages, linking documents and flagging discrepancies automatically.

KlearNow reports that AI‑powered customs solutions can cut document processing time by about 70 percent, improve practical compliance by roughly 95 percent, and reduce operational costs by about 90 percent in some user cases. Their platform focuses on recognizing and extracting data from multi‑format documents, running automated compliance checks, and providing real‑time visibility throughout the clearance process.

Linbis explains that modern customs automation tools integrate with transportation management, warehouse management, and enterprise resource planning systems, so the same data drives logistics, finance, and customs. They highlight benefits such as shorter clearance times, fewer documentation errors, and better real‑time tracking.

For an automation project team, this means your customs workflow can be designed much like a control system: standard inputs, automated validation logic, clear exception handling, and real‑time monitoring. Selecting forwarders and brokers that invest in these platforms is no longer a luxury; it is a way to protect your schedule and reputation.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Despite all the tools and expertise available, automation projects still run into the same customs problems again and again. The patterns in the guidance from Dimerco, SaraPSL, Ship4wd, Welke, Invensis, and others are remarkably consistent.

Incomplete or inconsistent documentation is the most common failure mode. Commercial invoices that lack detail, packing lists that do not match the hardware, or missing certificates of origin invite scrutiny. Customs agencies treat sloppy paperwork as a red flag. The practical fix is to standardize your documentation templates, train suppliers on them, and have an internal review before anything is filed.

Incorrect HS classification is another top risk. Dimerco and SaraPSL both warn that misclassification can change duty rates, trigger extra inspections, and in some cases bring fines. Over time, a pattern of misclassification can also attract higher scrutiny. For automation equipment, where modules and components can be complex, it is worth investing in expert classification support and, where appropriate, seeking written rulings as CBP suggests in its importer tips.

Undervaluation or misdeclared value may seem tempting as a way to cut duties, but Welke and others point out that authorities routinely uncover such practices. Penalties, back‑duties, and additional audits quickly outweigh any short‑term savings. Keeping clear proof of payment and aligning invoices with actual commercial terms is essential.

Missing permits or partner‑agency approvals can stop a shipment in its tracks. Freightclear, Freightos, and CBP all stress that commodity‑specific regulators may have their own documentation and standards. If your automation equipment includes features that fall into regulated categories, you must identify that early and work through the relevant agency’s process before shipping.

Late filings, especially for pre‑arrival security declarations, are another avoidable problem. Ship4wd highlights that missing Importer Security Filings or submitting them late leads to penalties and holds. Incorporating these filings into your project schedule and delegating them clearly to a broker or logistics lead prevents last‑minute surprises.

Finally, unclear Incoterms and responsibility boundaries create confusion at the worst possible moment. Dimerco and Inbound Logistics remind importers that Incoterms define who pays for what, including duties and clearance. For automation projects, this agreement should be explicit in your purchase contracts, not negotiated on the dock.

A Project‑Level Playbook for Automation Imports

Treating customs as an integrated workstream in your automation project makes a tangible difference. Combining the best‑practice recommendations from CBP, Globalia, Invensis, and logistics providers, a pragmatic playbook looks like this.

Start classification and regulatory research when you start detailed design. As soon as you know the major equipment families, initiate HS classification with your broker and check for potential anti‑dumping, countervailing, or special duties. At the same time, identify whether any partner agencies are likely to be involved.

Define Incoterms and customs responsibilities in the commercial strategy. Decide whether you or your supplier will act as importer of record, who will own the customs bond, and whether the pricing is structured as Delivered Duty Paid or Delivered Duty Unpaid. Make sure this aligns with your risk appetite and your customer’s capacity to handle customs.

Select brokers and forwarders based on their ability to handle complex machinery, integrate systems, and work proactively. Dimerco, Welke, and Linbis all highlight the value of digital capabilities, integration with freight systems, and industry experience. For automation, choose partners who understand machinery codes and have dealt with similar projects before.

Standardize documentation with templates and training. Borrowing from Freightos and Welke, create standard commercial invoice and packing list templates that include all required data fields. Train your suppliers to fill them out accurately and completely. Implement an internal review checklist before documents go to the broker.

Leverage automation where it truly helps. Following the direction described by Strixsmart, KlearNow, Linbis, and CargoEZ, integrate your purchasing, logistics, and customs data where possible. Use automated document ingestion and validation to catch discrepancies early, and rely on real‑time dashboards to monitor clearance status across all project shipments.

Finally, build customs milestones into your project schedule. CBP and ATS emphasize that entries can be filed before arrival and that clean entries typically clear in one to three days. Plan around that rather than assuming zero delay, and always keep a buffer for inspections. For critical go‑live dates, alternative plans for partial commissioning with available equipment can reduce the impact of unforeseen holds.

Short FAQ for Automation and Control Imports

Do I really need a customs broker for automation equipment? Legally, many countries, including the United States, allow importers to file entries themselves. CBP and articles from Dimerco, Clearit USA, and Welke all acknowledge that some firms do this successfully. However, for high‑value, complex machinery and automation hardware, these same sources strongly recommend working with a licensed broker, especially for newer or smaller importers. The time saved, the reduction in errors, and the protection against penalties usually outweigh the brokerage fee.

How early should I start customs work relative to shipment? Guidance from Dimerco, Ship4wd, and CBP points in the same direction: start as early as possible. Security filings for U.S. ocean shipments are due at least 24 hours before loading, and CBP will accept customs entries several days before arrival. In practice, for a significant automation shipment, you should aim to finalize HS classifications and documentation weeks before departure, so that filings can be made as soon as transport bookings are confirmed.

What if the equipment is only temporary, such as for a demo or trade show? UPS and Welke describe mechanisms such as temporary import bonds and international carnets that allow temporary imports without paying full duties and taxes, provided the goods are re‑exported within defined timeframes. The eligibility rules, paperwork, and guarantees are specific, and misuse can lead to full duty liability. If you are bringing automation equipment into a country for trials, demonstrations, or short‑term projects, discuss temporary entry options with your broker at the planning stage rather than assuming standard procedures will cover you.

Closing Thoughts

Customs is not an administrative footnote to an automation project; it is a technical and commercial constraint as real as power, floor space, or safety standards. The encouraging part is that the playbook for doing it well is now well documented by CBP, freight providers, and customs specialists, and increasingly supported by automation and AI tools that match the sophistication of the equipment you are importing. Build customs clearance into your project from day one, surround yourself with the right expertise, and your robots, drives, and control systems will spend their time on the plant floor instead of in a bonded warehouse.

References

- https://www.cbp.gov/trade/basic-import-export

- https://www.invensis.net/blog/customs-compliance-best-practices

- https://www.atsinc.com/blog/united-states-freight-customs-clearance-process

- https://cargoez.com/blog/automate-customs-compliance-process

- https://clearitusa.com/best-practices-first-time-us-importers/

- https://customscity.com/customs-clearance-and-compliance-10-tips-to-avoid-bottlenecks/

- https://freightclear.com/importing-construction-machinery-to-the-usa/

- https://www.klearnow.ai/unlocking-efficiency-in-global-trade-a-comprehensive-guide-to-customs-clearance-services/

- https://blog.sarapsl.com/posts/manufacturing-equipment-customs-clearance

- https://ship4wd.com/logistics-shipping/expedited-customs-clearance

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment