-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Overstock Mitsubishi Servo Drives: Turning Surplus Motion Control Into A Strategic Asset

As a systems integrator, I am used to walking into plants and seeing the same sight: a row of untouched Mitsubishi servo drives still in their boxes, everything from MR‑JE to MR‑J4 and MR‑J5, sitting on a shelf “just in case.” Those boxes represent real cash, real space, and real risk. The good news is that surplus Mitsubishi motion control hardware does not have to be dead weight. Handled correctly, it can be an asset that buys you uptime, flexibility, and even new capital. Handled badly, it quietly drains your budget and complicates every future project.

This article looks at surplus Mitsubishi servo drives with two mindsets: how to manage and monetize the overstock you already own, and how to safely take advantage of other companies’ surplus when you are buying on the secondary market. The focus is pragmatic: what works in a real plant, with real lines, under real schedule pressure.

What Surplus Mitsubishi Motion Inventory Really Is

Excess inventory, in the language of supply chain specialists, is stock that sits beyond realistic demand and beyond a rational, cost‑effective level for your operation. Cyzerg, nVentic, and Industrial Supply Magazine all make the same point in different words: surplus ties up working capital, inflates storage and handling costs, and increases the risk that your parts become obsolete before they are used.

EOXS and Hilco APAC go a step further and frame excess inventory as both a burden and an opportunity. The burden is obvious: you pay for space, insurance, and management time. The opportunity comes when you treat that stock as a pool of value that can be redeployed, monetized, or used to make your supply chain more resilient. That framing is particularly relevant for motion control hardware, because a Mitsubishi servo drive is not a disposable commodity. It is a high‑value, long‑lived asset that can either keep your lines running or fund your next upgrade, depending on how you treat it.

In more quantitative terms, Industrial Supply Magazine cited an estimate that manufacturers and distributors were carrying hundreds of billions of dollars in surplus and overstock even in the early 2000s. The number today is certainly higher. Your surplus drives are a tiny slice of that picture, but the mechanics are the same: unless you deliberately decide what to do with them, the default outcome is wasted money.

Why Servo Drives Are Not Typical Spare Parts

Before you can manage surplus Mitsubishi drives intelligently, you have to respect what they are and how they behave in an automation system.

ISA’s coverage of servo motion basics describes servos as sophisticated closed‑loop systems that coordinate position, speed, and torque across one or many axes. ADVANCED Motion Controls and BlueBay Automation add the engineering detail: a servo system consists of a motor, a drive (or amplifier), a controller, and a feedback device, all tied together with rigorous control loops. The drive does not simply “turn the motor on.” It closes current, velocity, and sometimes position loops at high bandwidth, regulates power, enforces protection limits, and talks to your PLC or motion controller over deterministic networks.

That means a surplus Mitsubishi servo drive sitting on a shelf is not interchangeable with any other power electronic box. It is wired into your ecosystem in very specific ways. It expects particular encoders, particular networks (SSCNET, CC‑Link IE variants, EtherCAT, Ethernet/IP, PROFINET), particular supply voltages, and particular control modes. A mis‑match in any of those dimensions can turn a bargain surplus drive into an expensive troubleshooting exercise.

The upside is that when you do match those dimensions, Mitsubishi servo platforms like MELSERVO‑J4 and MELSERVO‑J5, described by Adroit Technologies and Kpower as high‑performance, tightly integrated parts of the Mitsubishi ecosystem, can deliver years of service. That is precisely why they are worth managing thoughtfully when they are in surplus.

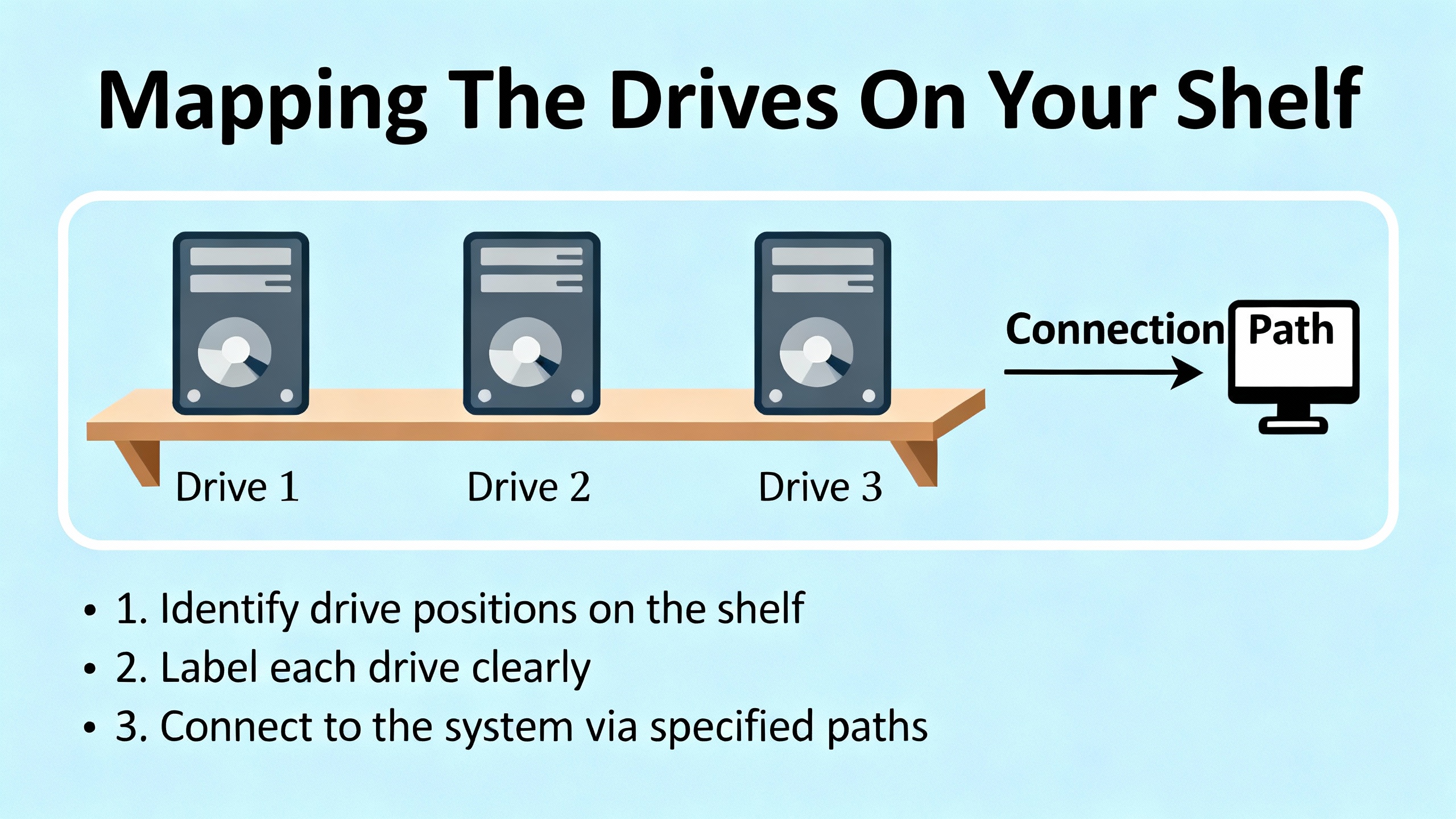

Mapping The Drives On Your Shelf

Decoding Mitsubishi Servo Drive Part Numbers

One of the best practical guides to Mitsubishi servo amplifiers comes from a Gibson Engineering Support Community article that breaks down a typical part number such as MR‑J4‑20A1‑RJ. In that example, “MR” identifies a general‑purpose servo amplifier, “J4” is the series, “20” indicates 200 watts of power, “A” identifies the control type as a digital I/O version, “1” shows it is a 100 V‑class amplifier, and “RJ” indicates that Safe Torque Off (STO) is present.

Gibson’s explanation generalizes across the family. Mitsubishi servo amplifiers typically encode the series (J4, JE, JN, J5, JET and others), the power rating, the control type letter (A, B, BF, C, G, TM), optional voltage modifiers for 100 V or 400 V classes, and suffixes marking special features such as STO. From a surplus‑management perspective, this matters because the suffixes and control type letters tell you where that drive can realistically be reused.

Control types fall into two broad categories. Digital I/O controlled drives, usually A‑type, take pulse and direction signals or table/program mode commands from 24 V I/O, and are attractive for low‑cost, often single‑axis motion. Network‑controlled drives (B/BF, C, G, TM) rely on SSCNET fiber, CC‑Link IE Field Basic, CC‑Link IE TSN, EtherCAT, PROFINET, Ethernet/IP, or similar networks. Gibson’s article names options such as B/BF on SSCNET, C on CC‑Link IE Field Basic, G and GF on various CC‑Link IE networks and EtherCAT, and TM versions that talk EtherCAT, Ethernet/IP, or PROFINET for third‑party PLC integration.

When you look at your surplus rack, start by decoding these fields. A batch of MR‑JE‑A amplifiers has a very different reuse profile than a set of MR‑J4‑GF or MR‑J5‑G‑N1 units, even if the wattage is similar.

Mitsubishi Servo Families Commonly Found In Surplus

Various sources, including Gibson Engineering, Adroit Technologies, Kpower, and Do Supply, describe the current and legacy MELSERVO families. The table below condenses some of those descriptions that are relevant when you are staring at a mixed surplus pile.

| Series | Typical role in Mitsubishi lineup | Example power and supply ranges mentioned in sources | Notable features from sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| MR‑JN | Simple, pulse/direction‑only amplifiers for straightforward applications | 100 V and 200 V systems, with motors and outputs up to about 400 W | Focused on basic point‑to‑point motion where cost matters more than advanced networking |

| MR‑JE | General‑purpose, lower‑cost servo line | 200 VAC, up to around 3 kW in Gibson’s overview | A, BF, and C control types; 17‑bit encoders; BF versions add STO; used widely in general automation |

| MR‑J4 | High‑performance, broad‑range “workhorse” series before J5 | 24/48 VDC and 100–400 VAC options from roughly 10 W up to around 55 kW | A, B, GF, and TM variants; 22‑bit encoders; supports multiple networks including SSCNET and CC‑Link IE |

| MR‑JET | Network‑only alternative to J5, aimed at value‑oriented systems | 200 VAC and 400 VAC options up to about 3 kW in Gibson’s description | G and G‑N1 only; 22‑bit encoders; positioned as step‑up from JE and cost‑reduced option vs J5 |

| MR‑J5 | Latest flagship servo series for demanding applications | 200 VAC and 400 VAC, with outputs from about 100 W up to around 22 kW | 26‑bit encoders, ultra‑fast control response, predictive maintenance features highlighted by Adroit |

| MR‑J2 / J3 | Earlier Melservo generations still in service and common in spares and surplus, per Do Supply | Guide examples span from roughly 0.4 kW up through several kilowatts | Multi‑mode control (torque, speed, position) on many models; designed for 200–240 VAC, often with SSCNET |

| HA‑FF63 etc. | Combined motor/servo amplifier and related units in the Do Supply survey of Mitsubishi drives | Do Supply discusses examples as low as about 0.1–0.75 kW and motor speeds to 4,000 rpm | Used where integrated motor‑drive designs or specific mechanical form factors are required |

This is not a catalog; it is a way of thinking about your pile of drives. MR‑J5 units represent the current top of the line and integrate tightly with Mitsubishi’s broader automation ecosystem. MR‑J4 remains widely used, with a large installed base. MR‑JE and MR‑JN are solid, lower‑cost solutions where extreme performance is not necessary. Earlier families like MR‑J2 and MR‑J3, highlighted in the Do Supply guide, still run plenty of machines but may fit best in like‑for‑like replacements or controlled legacy environments.

For each series, you then have to consider encoders, motors, and software. Adroit Technologies emphasizes pairing MR‑J4 and MR‑J5 with MR Configurator2 or MR Configurator3 and Mitsubishi PLC/SCADA tools for commissioning, tuning, and diagnostics. That software support is a real advantage when you are deciding whether a surplus drive is still a strategic spare or a candidate for sale.

How Surplus Servo Drives Accumulate

Across industries, the root causes of surplus inventory are well documented. EOXS cites overproduction, inaccurate demand forecasting, seasonal swings, and supply chain disruptions. nVentic calls out product lifecycle transitions, where optimistic new product launches and poorly managed end‑of‑life phases create piles of excess and obsolete stock. Leafio and Omniful add human factors such as intuition‑driven ordering, bulk purchase discounts, and special promotions or thresholds that nudge buyers toward ordering more than they need.

Leafio’s analysis is particularly blunt for intuition‑based ordering: they report that a very high fraction of orders placed “by gut feel” rather than by data end up as excess. Industrial Supply Magazine warns about vendor super‑sales with weak return on investment, where attractive discounts lead to large orders without adequate attention to real demand.

Translated into Mitsubishi motion control, those general patterns look very familiar. A plant upgrades a line from MR‑J3 to MR‑J4 or MR‑J5 but buys a large buffer of both old and new drives “just to be safe,” then never consumes most of them. A machine builder commits to a bulk purchase of MR‑JE‑C amplifiers to hit a supplier discount, then shifts the standard architecture to G‑type Ethernet drives and strands the earlier stock. A program manager drives a last‑minute design change in favor of a different network (for example, from SSCNET to EtherCAT), leaving a genuine surplus of good drives that simply do not fit the new design.

ISA and ADVANCED Motion Controls point out that modern servo systems are multi‑axis, multi‑component architectures. When your PLC platform, fieldbus, or machine performance requirements change, entire blocks of hardware can quietly slide from “key spare” to “surplus” even though nothing is wrong with the drives themselves. Without a conscious process, that shift happens ad‑hoc and is noticed only when the storeroom is full.

Keep, Redeploy, Or Sell: A Structured Decision For Surplus Drives

Hilco APAC, EOXs, Sensible Micro, and others recommend a structured approach to surplus inventory: audit, segment, redeploy where it makes sense, and monetize where it does not. That mindset works well for servo hardware if you add a layer of technical triage.

Technical Triage: What Is Still Strategically Useful

When I walk through a surplus rack with a client, I start with technical fit before talking about price. Several questions matter immediately.

First, is the series still aligned with the company’s motion standards. If a plant has standardized on MR‑J5 and MR‑JET for all new lines, a stack of MR‑JE‑A pulse‑train amplifiers might still be worth keeping to support older standalone machines, but it probably should not be the backbone of any new design. Conversely, surplus MR‑J4‑GF or MR‑J5‑G drives that match existing CC‑Link IE or EtherCAT networks often qualify as high‑value strategic spares.

Second, does the control type match the control strategy. Gibson’s description of A‑type, B/BF, C, G, GF, and TM amplifiers is invaluable here. If every new cell uses CC‑Link IE Field Basic from the built‑in Ethernet port of Mitsubishi PLCs, then MR‑JE‑C or MR‑J4‑GF units are far easier to redeploy internally than SSCNET‑centric B‑type hardware, unless you plan to maintain motion cards for the long term. If you have embraced third‑party PLCs from vendors such as Beckhoff, Allen‑Bradley, or Siemens, TM‑type Mitsubishi drives with EtherCAT, Ethernet/IP, or PROFINET support can be ideal bridges between your existing motor technology and your non‑Mitsubishi control layer.

Third, does the power and voltage range line up with realistic future use. Do Supply’s guide walks through examples from low‑power 0.4 kW units up through multi‑kilowatt drives in the MR‑J2, MR‑J3, MR‑J4, and MR‑JE lines. Gibson’s overview notes MR‑J4 models from around 10 watts up to about 55 kW and MR‑J5 units from about 100 watts up to roughly 22 kW. If your new machines typically fall in the 1 to 3 kW window on 200 VAC, there is little reason to warehouse an oversized set of rare 400 VAC, 30 kW drives, except for the specific lines that use them.

Finally, check condition and tool support. Adroit Technologies emphasizes how MR Configurator tools streamline configuration, tuning, waveform analysis, and diagnostics for MR‑J4 and MR‑J5 series. Drives that integrate cleanly with those tools and your existing programming practices have more strategic value than orphan units that require legacy software or undocumented configuration files.

Commercial Segmentation: Value, Risk, And Time To Cash

Once you have a technical view, you can borrow the financial disciplines described by Industrial Supply Magazine, nVentic, Perceptive‑IC, and others. They recommend inventory segmentation schemes such as ABC classification by value, GMROI thresholds, and explicit lifecycle and risk tagging.

Applied to Mitsubishi drives, that means grouping surplus units by a mix of technical and commercial factors. You can place high‑value, current‑generation MR‑J5 and MR‑J4‑G or MR‑JET‑G amplifiers, aligned with your standard networks, into a “strategic spare” bucket with high service‑level targets. Mid‑value, mid‑generation MR‑JE or MR‑J3 drives that still fit certain lines go into a “tactical redeploy or sell” bucket. Obvious mis‑fits with no clear internal use, or hardware tied to obsolete architectures you are deliberately retiring, belong in a “sell or dispose” bucket.

Industrial Supply Magazine argues strongly for formal policies that keep days of supply low, align replenishment with product life cycles, and enforce rigorous write‑offs and scrapping for obsolete or de‑listed items. nVentic reinforces that chasing a notional “100 percent service level” across every item is a fast path to excess and obsolete inventory. For servo drives, that translates into being explicit about how many spares you really need for each platform, how many axes they cover, and how that number should change over time as lines are upgraded.

Choosing The Right Channel For Surplus Servo Drives

Once you know what you want to keep and what you want to move, the next decision is channel. The general guidance from Cyzerg, EOXS, Hilco APAC, Sensible Micro, and Leafio is consistent: prioritize redeployment where it makes operational sense, then use structured, multi‑channel sales to recover value, and consider donation or scrapping as a last resort.

For motion control hardware, redeployment often means moving drives and matched motors from one line, plant, or region to another that shares the same PLC platform and network. Hilco APAC and Industrial Supply Magazine both highlight internal redeployment as a powerful way to avoid buying new stock while reducing surplus elsewhere in the network. That only works if your technical triage says the drives are still aligned with your standards and if the logistics cost does not exceed the avoided purchase.

Selling into secondary markets can take several forms. Cyzerg and Hilco APAC mention online marketplaces, auctions, specialized liquidators, and targeted outreach to existing and new customers. Sensible Micro’s work in the electronics world shows how specialist partners can connect excess inventory to global buyers and use lifecycle analytics to time those sales before value drops sharply. Servo drives are well suited to these channels because they are compact, high value, and often in demand for maintenance and retrofit work. The key is to document part numbers, series, power ratings, and control types accurately so buyers know what they are getting.

If neither redeployment nor sale is realistic, EOXS, Industrial Supply Magazine, and Omniful describe donation and environmentally responsible disposal as balanced options. Donations to educational or non‑profit organizations can create social value and potential financial benefits, provided you address safety and liability. Scrapping should be a controlled, last‑resort choice, not an unexamined default.

Buying Surplus Mitsubishi Drives: Opportunity With Guardrails

So far, the discussion has assumed you are the one holding surplus inventory. Many integrators and end users are on the other side of the equation: they are buying overstock MR‑J3, MR‑J4, or MR‑JE units from distributors or other plants to avoid long lead times and reduce capital spend. That can be smart, but only if you adopt the selection discipline recommended by Kpower, ADVANCED Motion Controls, BlueBay Automation, and Do Supply.

Their collective message is consistent. Start from the application, not from the price tag. Define the mechanical motion profile, the torque and speed envelope, the duty cycle, and the environmental conditions. Confirm the electrical power and network architecture you will use. Only then should you match a drive.

From a surplus‑buying standpoint, several checks are non‑negotiable. The drive’s continuous and peak current ratings must be appropriate for the motor and load. Both ADVANCED Motion Controls and the Do Supply guide make it clear that undersized drives cannot meet performance requirements and oversized drives can cause poor control at the low end of their range or even damage motors if not configured correctly. The voltage class has to match your available supply, particularly if you are mixing 100 V, 200 V, and 400 V‑class equipment.

Network and control compatibility come next. Gibson and ISA emphasize that multi‑axis servo systems now rely heavily on deterministic Ethernet networks such as EtherCAT, CC‑Link IE TSN, PROFINET, or Ethernet/IP, or on dedicated motion networks like SSCNET. When you buy surplus, you need to be sure the G‑type or TM‑type Mitsubishi drive you are considering actually supports the fieldbus your PLC uses. A bargain EtherCAT‑only drive is of limited value if your plant standards and skillset revolve around CC‑Link IE. Conversely, surplus TM‑type drives can be a powerful way to bring Mitsubishi motors into a third‑party PLC environment, provided that network alignment is clear.

Environmental ratings and mechanical construction also matter. Do Supply notes that Mitsubishi drives are typically specified for operation from around 0 to 55 degrees Fahrenheit equivalent rather than extreme conditions, and that some models are IP00 open construction while others are enclosed and fan‑cooled. Venus Automation and other servo selection sources stress protecting drives and motors against dust, moisture, and aggressive chemicals with appropriate ingress protection and thermal management. When buying surplus, ensure that the enclosure style and environmental limits of the drive match where you intend to install it.

Finally, plan for commissioning and long‑term support. Adroit Technologies highlights how MR Configurator2 and MR Configurator3 simplify setup, tuning, and diagnostics for MR‑J4 and MR‑J5 drives. If you buy surplus models in those families, confirm you have access to the appropriate configuration tools and manuals. Make sure your team has or can acquire the necessary tuning and diagnostic skills; ISA notes that while modern servo systems are efficient and robust once commissioned, troubleshooting can be complex without the right expertise.

Using Surplus To Reduce Risk, Not Just Cost

When inventory specialists such as nVentic or Industrial Supply Magazine talk about service levels, they emphasize avoiding a naive pursuit of perfect availability on every SKU. It is better to segment, explicitly decide where very high availability is justified, and accept lower levels elsewhere. In motion control, surplus servo drives are one of the cleanest levers you have to raise service levels selectively where downtime is most expensive.

For a critical packaging line or a pharmaceutical blister pack machine of the kind ISA describes, a local spare MR‑J4 or MR‑J5 amplifier may prevent hours of production loss. In that context, holding some surplus is rational. For a low‑utilization auxiliary axis or a legacy machine scheduled for replacement, the same surplus unit may be better converted to cash and reallocated to more pressing investments.

The trick is to decide those roles deliberately. Industrial Supply Magazine advocates appointing explicit ownership for surplus, sometimes even a “surplus czar,” to coordinate between purchasing and sales in a distribution environment. In a plant or OEM, the equivalent is assigning clear responsibility between engineering, maintenance, and supply chain for deciding how many drives of each type to hold, how long to hold them, and when to trigger redeployment or sale.

A Practical Way Forward

If you have a wall of Mitsubishi servo drives today, do not treat it as an embarrassment. Treat it as a project. Start with a structured technical triage grounded in series, control type, power, and network compatibility. Use the language and categories from Gibson Engineering’s amplifier guide and the Adroit Technologies and Kpower overviews of MELSERVO platforms to sort the hardware into what fits your architecture and what does not.

Then layer in the commercial view that inventory specialists describe: segment by value and risk, decide where high service levels are truly warranted, and put time‑bound decisions in place for each group of drives. For stock that does not belong in your long‑term plan, follow the playbook from Hilco APAC, EOXS, Cyzerg, and Sensible Micro: prioritize internal redeployment, use professional secondary channels where appropriate, and treat scrapping or donation as controlled end points rather than quiet defaults.

On the buying side, hold surplus drives to the same engineering standards you apply to any new component. Select based on application requirements, verify power and network compatibility, respect environmental and safety limits, and make sure you have the right software tools and skills for commissioning. Saving a few thousand dollars on hardware is not worth weeks of debugging if the choice is misaligned with your control architecture.

In my role as a project partner, I measure success by stable lines, predictable behavior, and honest tradeoffs between risk, cost, and flexibility. Managed with that mindset, overstock Mitsubishi servo drives stop being a dusty liability and become a deliberate buffer that supports both uptime and capital planning.

Short FAQ

How many surplus Mitsubishi servo drives should I keep as spares. There is no universal number; it depends on the criticality of the line, lead times, and your standardization level. Inventory experts such as nVentic and Industrial Supply Magazine recommend segmenting items by importance and demand variability, then setting higher service‑level targets for critical items and lower targets elsewhere. For servo drives, that usually means holding more spares for current‑generation platforms that run high‑impact lines and fewer for legacy or low‑criticality equipment.

Is it wise to build new machines primarily on surplus MR‑J3 or MR‑J4 drives. From a systems integration standpoint, that depends on your lifecycle horizon and software strategy. Adroit Technologies positions MR‑J5 as the current flagship with advanced performance and predictive maintenance, while Gibson Engineering shows MR‑J4 and MR‑JE as still very capable. Using surplus MR‑J4 or MR‑JE drives can be reasonable for low‑ to mid‑criticality machines, especially if they align with your PLC and network standards and you have MR Configurator tools and expertise in house. For platforms expected to live many years and to integrate with evolving networks, it is usually better to design around current‑generation hardware and reserve surplus units primarily for spares and retrofits.

What is the safest way to start monetizing surplus Mitsubishi motion inventory. Begin with a focused inventory audit. Classify your drives by series, control type, and voltage; then apply the segmentation and lifecycle principles highlighted by Industrial Supply Magazine, EOXS, Hilco APAC, and Sensible Micro. Once you know which items have no clear future role, work with reputable resale partners or established channels in your industry, and share accurate technical data for each item. That reduces friction, improves pricing, and lets you steadily convert idle motion hardware into both cash and a cleaner, more intentional spares strategy.

References

- https://www.isa.org/intech-home/2020/november-december-2020/departments/servo-motion-control-basics

- https://www.plctalk.net/forums/threads/mitsubishi-servo-drive-selection.134490/

- https://blog.kpower.com/index.php?c=show&id=10507

- https://www.a-m-c.com/how-to-select-a-servo-drive/

- https://adroitscada.com/servo-systems/?srsltid=AfmBOorKgg7ioR-gs1gb6yJq9ZUlgVACNTPF9fNZXgaVujr8HXaVe2WO

- https://venusautomation.com.au/how-to-choose-the-right-servo-motor/

- https://hilcoapac.com/maximising-roi-best-practices-for-selling-excess-inventory/

- https://industrialsupplymagazine.com/pages/Management---Surplus-inventory-Avoid-it,-identify-it,-sell-it.php

- https://www.omniful.ai/blog/effective-strategies-manage-excess-inventory

- https://www.parkermotion.com/whitepages/servofundamentals.pdf

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment