-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

PLC Cost Comparison Guide: How to Evaluate Pricing for Industrial Controllers

Programmable logic controllers sit at the center of most modern plants. They quietly coordinate motors, valves, safety interlocks, recipe changes, and alarms twenty-four hours a day. When it is time to choose or replace a PLC platform, cost is always on the table, and the discussions usually start with one question: why does this controller cost several thousand dollars while another one with the same I/O count costs half as much?

After decades as a systems integrator, I have learned that a fair PLC price comparison is far more than a catalog exercise. The cheapest rack on paper can easily become the most expensive decision once software, engineering hours, downtime, and future expansion are included. In this guide, I will walk through a practical, experience-based way to evaluate PLC pricing using data points from engineering sources, vendor case studies, and procurement research, so you can defend your choice in both the control room and the boardroom.

What “PLC Cost” Really Means

At the simplest level, a PLC is an industrial computer that reads inputs from sensors, executes control logic, and drives outputs to actuators. Sources such as RealPars and Industrial Automation Co describe them as rugged industrial controllers built for real-time operation in environments where standard office PCs would not last. Academic work referenced by IEEE goes further and calls the control system the “brain” of process plants, from petrochemical to food processing.

Two big categories matter when you think about cost. The first is the controller type and hardware form factor. The second is the software, engineering, and lifecycle costs that follow you long after the purchase order is issued.

PLCs, PACs, and Controller Classes

Traditional PLCs were built around discrete control: turning devices on and off at the right time. Programmable automation controllers, often called PACs, combine industrial-grade CPUs with more open architectures and more powerful computation. IEEE research that benchmarked PLC and PAC platforms emphasizes that PACs tend to be better suited to advanced computation, open protocols, and future-oriented architectures, while PLCs are extremely robust for conventional logic and sequencing. In practice, many modern “PLCs” blur that distinction and deliver PAC-like capabilities.

Within both PLC and PAC families, you will typically encounter three main hardware classes, as described in a LinkedIn engineering brief on cost versus performance:

Compact or “brick” PLCs are single integrated units with fixed I/O and communication ports. They are easy to install, program, and maintain, and are ideal for small machines or standalone systems. Their fixed nature means lower hardware cost and smaller panels, but also less flexibility if the machine grows.

Modular PLCs consist of separate modules for CPU, power supply, I/O, communication, and expansion. You slide these modules onto a backplane to build exactly what you need. This architecture offers high flexibility and scalability, but the tradeoff is higher upfront controller cost, more panel space, and more wiring and assembly.

Micro PLCs are the smallest and simplest. They have few I/O points and minimal memory and communications. They are inexpensive and well suited for basic tasks such as lighting control, simple timers, counters, and a few sensors.

When you compare prices between platforms, always confirm which class you are looking at. A micro or compact controller from one brand will obviously cost less than a modular high-end CPU from another.

Typical PLC Price Bands by Brand and Class

Independent comparison work by Industrial Automation Co provides helpful ballpark figures for major brands. Actual prices vary by distributor, region, and discount, but the order of magnitude is consistent and good enough for budgeting and relative comparisons.

Below is a consolidated view of typical controller price bands derived from that analysis.

| Brand / family | Approximate entry controllers | Higher-end systems (CPU or main rack) | Typical positioning and notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Siemens (S7-1200, S7-1500) | Around $500.00 for an S7-1200 CPU | $2,000.00 and up for S7-1500, plus roughly 300.00–1,000.00 for I/O and communication modules | High-performance, feature-rich PLCs widely used in automotive and other complex automation; strong global support and advanced engineering tools such as TIA Portal. |

| Allen-Bradley Rockwell (CompactLogix, ControlLogix) | Roughly 1, 000.00–3,500.00 for CompactLogix CPUs | $5,000.00 and higher for ControlLogix processors, plus Studio 5000 programming software licenses typically above $500.00 | Premium ecosystem with very strong integration in North American plants; excellent for precision motion and large, integrated lines. |

| Mitsubishi Electric (FX, iQ platforms) | Base controllers starting around $300.00 | Larger modular systems with extensive I/O often up to about $1,500.00 | Cost-effective, reliable PLCs for small to mid-sized and high-speed repetitive operations, such as packaging lines. |

| Schneider Electric (Modicon M series) | Base models around $400.00 | IoT-enabled configurations, such as Modicon M580, exceeding $2,000.00 | Emphasis on energy efficiency and connectivity, with integration into EcoStruxure for Industrial Internet of Things applications. |

| ABB (AC500 series) | Entry CPUs starting near $800.00 | Rugged heavy-industry configurations for mining, oil, and gas reaching $3,000.00 or more | Built for harsh environments with strong diagnostics and interoperability; typically mid- to high-price tier. |

| Omron (CP1 and related series) | Entry controllers around $200.00 | Advanced models with vision and robotics integration up to about $1,000.00 | Compact, all-in-one PLCs well suited to small automation projects and integrated robotics or vision systems. |

Case studies in that same Industrial Automation Co work highlight why premium controllers can still be cost-effective when matched with the right application. A global automotive manufacturer that upgraded to Siemens S7-1500 reportedly reduced production downtime by about 30 percent due to faster processing and better analytics. A food and beverage plant that replaced aging equipment with Allen-Bradley CompactLogix saw production efficiency improve by roughly 25 percent and energy usage drop about 15 percent because of more precise process control.

At the same time, more affordable controllers can deliver very strong returns where requirements are moderate. Mitsubishi’s FX-series controllers contributed to around a 20 percent output increase in a packaging line by enabling high-speed modular expansion, and Omron’s compact PLCs cut defect rates by about 18 percent in an electronics manufacturer’s robotic soldering application.

When you compare quotes, put these brand-level price bands next to your performance needs and ask whether the premium you are paying will translate into similar tangible improvements.

The Other Half of PLC Cost: Software, Engineering, and Lifecycle

Hardware prices are only one piece of the puzzle. Industrial automation publications such as RealPars and Automate, along with procurement research from SpendEdge, consistently emphasize that software, engineering labor, and lifecycle costs often outweigh the controller price over the life of a system.

Software and Programming Environment

High-quality PLC software is not a commodity. An Automate editorial on buying PLC software underscores that motion and process control software must deliver very high precision and undergo extensive testing under realistic conditions. That level of assurance costs money, and it is reflected in both license fees and support contracts.

With some platforms, such as Rockwell’s Studio 5000, you need to budget separately for software licenses that can easily exceed $500.00 per seat. Other vendors bundle basic programming tools with the hardware and charge only for advanced options. Besides license cost, you pay for training and ramp-up time. Simcona, an industrial panel builder, notes that many teams use only a fraction of the available software features, sometimes as little as about 20 percent of what is offered. Paying for advanced capabilities you will never use is a silent form of overspending.

Integration is another driver. Automate’s guidance stresses that your PLC software must coexist with other automation software written by different engineers, often in different languages, and that open communication protocols are critical. If you pick a platform with closed or unusual protocols, you may save a little on the controller and lose it many times over in integration headaches.

On the other end of the spectrum, new industrial controllers like the Norvi ESP32-based units are deliberately built around widely known development environments such as Arduino IDE and ESP-IDF, with integrated Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and industrial analog ranges like 0–10 V and 4–20 mA. Their main economic argument, according to Norvi’s own material, is significantly lower hardware and software cost for small to medium projects by reusing existing programming skills and lowering the barrier for diagnostics and remote monitoring.

Engineering, Panels, and Installation

Hardware and software sit inside a larger system that must be designed, built, and validated. Simcona recommends starting any PLC selection with a clear process schematic that enumerates field devices, physical constraints, and all analog and discrete I/O. Underestimating I/O count or communications needs is one of the fastest ways to incur unplanned cost, because adding modules later may require panel rework and additional licenses.

Panel size, power supplies, and I/O terminal strips all scale with the controller architecture. Modular PLCs usually require larger enclosures and more wiring than compact bricks, and that translates directly into labor hours. In one RealPars case study, a refinery’s use of multiple Siemens S7 processors and dozens of remote I/O panels to manage about 10,000 I/O points illustrates how quickly infrastructure costs grow with scale.

Installation cost is also affected by environmental demands. Simcona warns that PLC failures are often due to heat, moisture, chemicals, electromagnetic interference, dust, and vibration. Many standard PLCs are specified for operation around 32 to 130°F; outside that band, you need better environmental protection or ruggedized hardware, which increases hardware cost but often pays for itself by avoiding failures.

Finally, component availability can dominate cost in tight markets. Simcona points out that electronic component shortages have pushed some PLC lead times up toward a year. If a premium platform is available in eight weeks and a cheaper one is twelve months out, the “expensive” choice may be the only economically viable option once lost production is considered.

Maintenance, Downtime, and Support

The controller you choose will be updated, patched, and maintained for many years. Cybersecurity and support policies affect cost at least as much as the sticker on the CPU.

As plants connect more PLCs to networks, integrate with IoT platforms, and experiment with cloud-based analytics, attack surfaces grow. Simcona cites data that roughly 95 percent of cybersecurity breaches are caused by human error, and lists common weaknesses such as lack of authentication, lack of encryption, and unpatched systems. Cleaning up after an incident is orders of magnitude more expensive than paying for secure architectures, up-to-date firmware, and proper authentication mechanisms from the start.

Support responsiveness is easier to ignore until something goes wrong. Market-intelligence firms like SpendEdge, which profile suppliers such as Siemens, ABB, Rockwell, Honeywell, GE, Schneider, Omron, Eaton, and Hitachi, emphasize post-sales service capability and extended warranty support as key selection criteria because they materially affect downtime risk and costs.

Market Trends: How PLC Prices and Procurement Are Moving

Beyond individual brands, it helps to understand how the overall PLC procurement market is evolving. Multiple reports from SpendEdge and press releases summarized by PRNewswire and Le Lézard give a consistent picture.

Between 2020 and 2024, one SpendEdge procurement intelligence report expects incremental PLC market spend of about $1,000,000,000, with a compound annual growth rate estimated around 5.92 percent. A related pricing and category-management report focusing on 2022 through 2026 projects spend growth at a compound annual rate of about 4.16 percent and an incremental spend of roughly $1,163.07 million. Across these sources, PLC prices are generally forecast to rise by about 2 to 5 percent over the forecast periods, with suppliers holding moderate bargaining power.

For buyers, moderate supplier power usually means you will not see deep, across-the-board price cuts just by asking for them. Instead, procurement specialists are advised to lean on pricing models and total cost of ownership. The same reports describe several pricing approaches: fixed pricing, cost-plus, volume-based models, and spot pricing. Each has pros and cons. Fixed pricing simplifies budgeting but shifts risk to suppliers. Cost-plus offers transparency but can dull a vendor’s incentive to control cost. Volume-based arrangements can unlock meaningful discounts if you standardize on one platform across multiple sites.

SpendEdge’s guidance also dives into category management objectives such as supply assurance, TCO reduction, demand forecasting, and adherence to regulations. From a project manager’s standpoint, this means PLC cost comparison should include questions about supplier financial health, their ability to counter cybersecurity threats, and their capacity to meet future demand spikes without unreasonable price moves.

A Practical Framework for Comparing PLC Offers

When I sit with a client to review competing PLC proposals, we do not start with the cheapest line in the spreadsheet. We walk through a structured comparison that reflects both engineering realities and commercial intelligence. You can do the same using the following approach, summarized in prose rather than a checklist.

First, ground yourself in the process, not the catalog. Use a process or equipment schematic to identify every sensor, actuator, and subsystem. Think about response-time needs: Norvi’s guidance on controller selection reminds us that high-speed packaging and precision manufacturing may need microsecond-level responses, whereas HVAC or slow batch processes can tolerate longer scan times and cheaper control hardware. Document current and likely future I/O, including digital and analog inputs, relay or transistor outputs, and any special interfaces, so that you do not under-specify the platform.

Next, pick the appropriate controller class before comparing brands. If the application is a simple stand-alone machine or a small building system, a micro or compact PLC from Omron, Mitsubishi, or similar vendors may meet your needs at entry prices around $200.00 to $300.00. If you plan to scale the system or integrate advanced motion control and analytics, a modular platform from Siemens, Allen-Bradley, or Schneider, with CPUs in the $500.00 to several thousand dollars range, may be justified because of their expandability and software ecosystems. The LinkedIn overview of compact, modular, and micro PLCs is clear that modular systems carry higher hardware and installation cost but offer flexibility that compact bricks cannot match.

Then, evaluate brand ecosystems and software carefully. RealPars, in its comparison of Siemens, Allen-Bradley, Mitsubishi, and Schneider, indicates that Siemens and Allen-Bradley excel in high-performance and motion-heavy environments, at the cost of higher processor prices and sometimes more complex messaging or setup. Mitsubishi delivers strong value for small and mid-sized systems, while Schneider’s Modicon line is praised for versatility and integration. Combine those technical traits with software considerations from Automate: precision, testing rigor, integration capability, and customization flexibility. Ask yourself what your maintenance technicians already know, how often you will need vendor support, and whether your company will benefit more from a unified high-end ecosystem or from lower-cost, easier-to-learn platforms.

After that, compare total cost of ownership over a realistic horizon, such as ten years. Incorporate hardware racks and modules for base scope and expected expansions, programming licenses and renewals, engineering hours for design and commissioning, control panel fabrication, communication networking equipment, and maintenance contracts. Include some estimate for downtime cost and mean time to repair, even if qualitative, since case studies show that a thirty percent reduction in downtime or a double-digit boost in efficiency can dwarf the difference between a $1,500.00 and a $5,000.00 CPU.

Finally, bring in procurement levers. Use market intelligence from firms like SpendEdge to understand typical pricing levels, where your supplier sits in the competitive landscape, and which negotiation levers are realistic. For example, you might accept a slightly higher list price in exchange for fixed pricing over multiple years, or negotiate volume-based discounts tied to a global standardization initiative. You might also extract value from extended warranties, included training, or better cybersecurity posture, all of which have cost implications that will not appear in the base controller price.

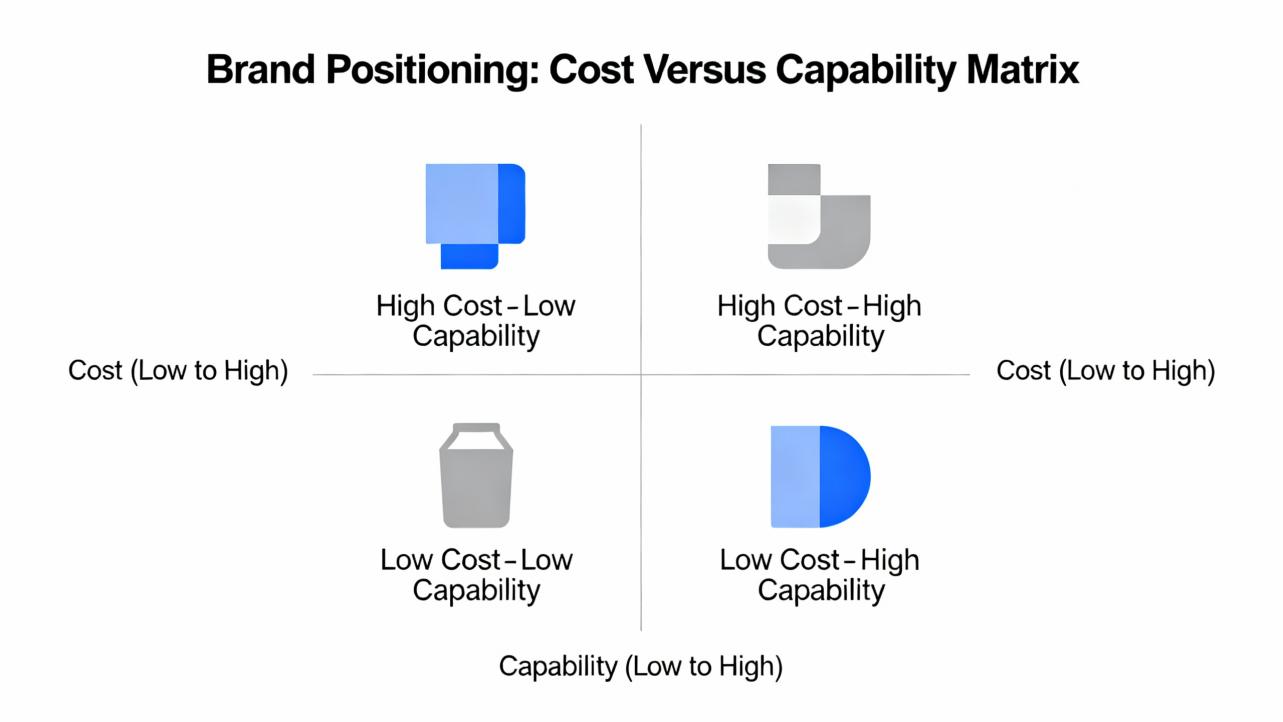

Brand Positioning in Cost Versus Capability

Putting everything together, a pattern emerges that is consistent across technical sources and market analyses.

At the high end, Siemens and Allen-Bradley anchor the premium segment. Siemens’ S7 range has been a staple in process industries for decades, and RealPars highlights its strong modularity and Ethernet and OPC-UA integration. Allen-Bradley’s ControlLogix and CompactLogix lines sit at the center of many North American plants, especially where complex motion control and tight integration with Rockwell’s broader ecosystem matter. Industrial Automation Co data and case studies show why plants are willing to pay mid-to-high four-figure amounts for these CPUs: documented reductions in downtime, better analytics, and faster troubleshooting.

In the mid-range, Schneider Electric and ABB offer compelling options. Schneider’s Modicon series is known for reliability and energy efficiency, along with strong connectivity via Ethernet and Modbus, and integration into EcoStruxure for IoT-style architectures. ABB’s AC500 series is designed for harsh environments and heavy industries, with advanced diagnostics and third-party interoperability. With entry CPUs around $800.00 and advanced heavy-industry configurations at $3,000.00 or more, ABB’s focus is not minimum cost but ruggedness and availability in extreme conditions. These platforms are attractive where environmental demands or energy efficiency targets are central.

At the value end of the established PLC spectrum, Mitsubishi and Omron stand out in the research. Mitsubishi Electric’s compact and modular PLCs, with base models around $300.00 and larger setups up to $1,500.00, are aimed squarely at small and mid-sized automation projects and high-speed but repetitive operations. Omron’s CP1-series PLCs start near $200.00 and scale to about $1,000.00 for advanced controllers with integrated vision, ideal for small robotics and electronics manufacturing. They deliver meaningful case-study results such as twenty percent higher throughput or eighteen percent fewer defects, without the cost of a high-end platform.

Emerging microcontroller-based industrial controllers, such as Norvi’s ESP32 and STM32-based devices, push the cost envelope further by integrating Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and industrial analog ranges directly on the controller at significantly lower cost than traditional PLCs. They are not a drop-in replacement for a process refinery DCS, but for building automation, test rigs, or small manufacturing cells, they can offer strong return on investment through low upfront cost and built-in connectivity for IoT and remote diagnostics.

Common PLC Cost Traps and How to Avoid Them

Most painful PLC cost stories I see fall into a few predictable patterns, all of which are highlighted in one way or another in the sources we have discussed.

One trap is overspecifying functionality. Simcona’s observation that about eighty percent of software features in many systems are rarely used is borne out in the field. Teams sometimes insist on the top-tier CPU “just in case,” then only use basic ladder logic. Buying controllers whose advanced features you will never use is money left on the table.

An opposite trap is underestimating integration and training costs. Automate’s article on buying PLC software warns that complex integration across multiple systems and engineers is the norm. Choosing a low-cost platform without considering your team’s skills, the learning curve, and the availability of training and documentation often leads to delays and frustration. Conversely, choosing a more expensive vendor that your technicians already know can reduce ramp-up time and maintenance costs.

Ignoring lead times is another trap. The ongoing component shortages described by Simcona mean that the cheapest quote may not be the best option if it implies delivery next year. If a platform with slightly higher unit cost can be delivered in weeks rather than months, the effective cost per unit of production can be far lower.

Cybersecurity shortcuts also backfire. With Norvi and Simcona both emphasizing modern connectivity and the human factor in breaches, it is worth remembering that PLCs are increasingly connected to IoT and cloud systems. Controllers that are difficult to patch or have limited support for modern encryption and authentication may expose you to risks that far outweigh any savings. Procurement reports now explicitly include supplier capabilities to counter cybersecurity threats as a selection criterion, which shows how seriously buyers are starting to treat this dimension.

Finally, environmental misalignment costs money. Using a standard office-grade enclosure where there is oil mist, corrosive vapors, or tire-shredding vibration may save a little at purchase time and cost you multiple replacements later. Checking operating temperature ranges, environmental ratings, and compliance with relevant standards during selection is a simple way to avoid that trap.

FAQ: Practical Questions About PLC Cost Comparison

Is it worth paying more for a well-known PLC brand?

It depends on how important ecosystem, support, and advanced features are for your specific application. RealPars and Industrial Automation Co both present examples where high-end Siemens and Allen-Bradley platforms delivered measurable benefits like significant downtime reduction, efficiency gains, and energy savings. If your plant is complex, needs tight integration with existing systems, and depends heavily on fast motion control or advanced diagnostics, the premium may easily pay for itself.

On the other hand, for modest automation tasks with limited I/O and relatively simple logic, vendors like Mitsubishi and Omron deliver capable controllers at a fraction of the price. Norvi’s microcontroller-based industrial units push cost even lower for small, IoT-heavy projects. The key is to be honest about your needs and future expansion plans, and to compare total cost of ownership, not only the purchase price.

How should I budget for PLC software and engineering?

Based on the guidance from Automate and Simcona, start by listing all required development tools, runtime licenses, and any optional packages such as motion, safety, or advanced diagnostics. For some ecosystems, these can add hundreds of dollars per seat. Add training time for your team to become productive, especially if you are switching vendors. Then consider how the software framework will affect development, troubleshooting, and future changes. A platform that reduces debugging time or simplifies adding new I/O may justify higher license fees.

Engineering and panel-building hours should be estimated alongside. System integrators and panel shops will often give you a breakdown of design, programming, panel fabrication, installation, and commissioning. Use those to compare platforms. A controller that shortens commissioning or simplifies future modifications can save more than it costs, particularly if you plan to replicate the design across multiple lines or sites.

Do IoT, AI, and newer PAC architectures change the cost equation?

They do, especially over the long term. IEEE research on PACs and a more forward-looking LinkedIn analysis of PLC-based controllers through 2033 both emphasize that controllers are moving toward edge computing, IoT integration, embedded analytics, and stronger cybersecurity. This evolution can shift value away from pure hardware horsepower toward features that enable condition monitoring, predictive maintenance, and secure remote access.

Low-cost platforms like Norvi’s ESP32-based controllers integrate IoT capabilities such as Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, MQTT, and Modbus over Ethernet or RS-485 directly into the hardware at an attractive price point. High-end PAC-style systems integrate advanced computing power and open architectures that are better suited for complex analytics and large-scale integration. When you do your cost comparison, consider whether you will want to exploit these capabilities in the next few years. If so, picking a platform that supports them natively may avoid expensive retrofits later.

Closing Thoughts

When you strip away the marketing and brand loyalty, PLC cost comparison is about matching the right level of capability to the real needs of your process, then buying that capability on terms that protect your budget over the life of the system. Hardware list price is important, but the best decisions come from combining process understanding, careful sizing, ecosystem and software evaluation, and informed procurement tactics.

From one integrator to another, the most reliable way to avoid regrets is to treat your PLC choice as a long-term partnership decision rather than a one-time purchase. If you align controller class, brand, and commercial model with the way your plant operates and grows, you will rarely find yourself explaining cost overruns in the control room or the boardroom.

References

- https://scholarworks.uni.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1661&context=etd

- https://www.automate.org/editorials/best-practices-when-buying-plc-software

- https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6720620/

- https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/industrial-pricing-strategies-and-policies/34477325

- https://www.plctalk.net/forums/threads/plc-cabinet-price.92183/

- https://www.accio.com/business/hot-selling-plc-and-hmi-with-competitive-prices

- https://www.controleng.com/how-to-lower-plc-software-costs/

- https://www.lelezard.com/en/news-19487810.html

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/exploring-dynamics-plc-based-controller-key-insights-r14pf

- https://norvi.io/how-to-choose-the-best-plc-for-your-automation-project-to-boost-efficiency-productivity-and-cost-reduction/

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment