-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Quality Assurance Standards for Used Industrial Controls: A Systems Integrator’s Playbook

Used industrial controls are back in style. Long lead times, budget pressure, and sustainability targets are all pushing plants and OEMs to reuse control panels, PLCs, drives, and safety devices instead of buying everything new.

After a few decades in system integration, I can tell you that used controls can be a perfectly sound strategy—or a slow-motion disaster—depending entirely on how disciplined your quality assurance really is.

This article lays out a practical framework for quality assurance standards around used industrial controls, grounded in established international standards and real project experience. The goal is simple: make sure every reused component is safe, compliant, secure, and supportable, with no surprises during commissioning or audits.

Why Used Controls Are Not “Plug-and-Play”

On paper, reusing controls looks easy. The cabinet powered a line last year, the PLC still boots, the drives turn, the HMI lights up. In reality, you are inheriting someone else’s design assumptions, documentation gaps, field modifications, and aging hardware.

In modern plants—oil and gas, pharmaceuticals, power, discrete manufacturing—control systems are bound by standards that govern safety, interoperability, cybersecurity, and documentation. Articles from instrumentation and control engineering practitioners stress that these standards are not “nice to have”; they are the backbone of safe and reliable operation.

When you bring used controls into that environment, you take on several risks if you do not formalize QA around them. You may inherit non‑compliant wiring that conflicts with current NFPA 79 expectations for industrial machinery. You may reintroduce a panel that was never tested to the current IEC 61439 requirements for low‑voltage switchgear assemblies. You may plug a legacy PLC into a network that is now designed around ISA/IEC 62443 and NIST SP 800‑82 guidance on industrial cybersecurity and create an attack path you never intended.

This is why used industrial controls need a defined quality assurance standard, not an ad hoc visual check.

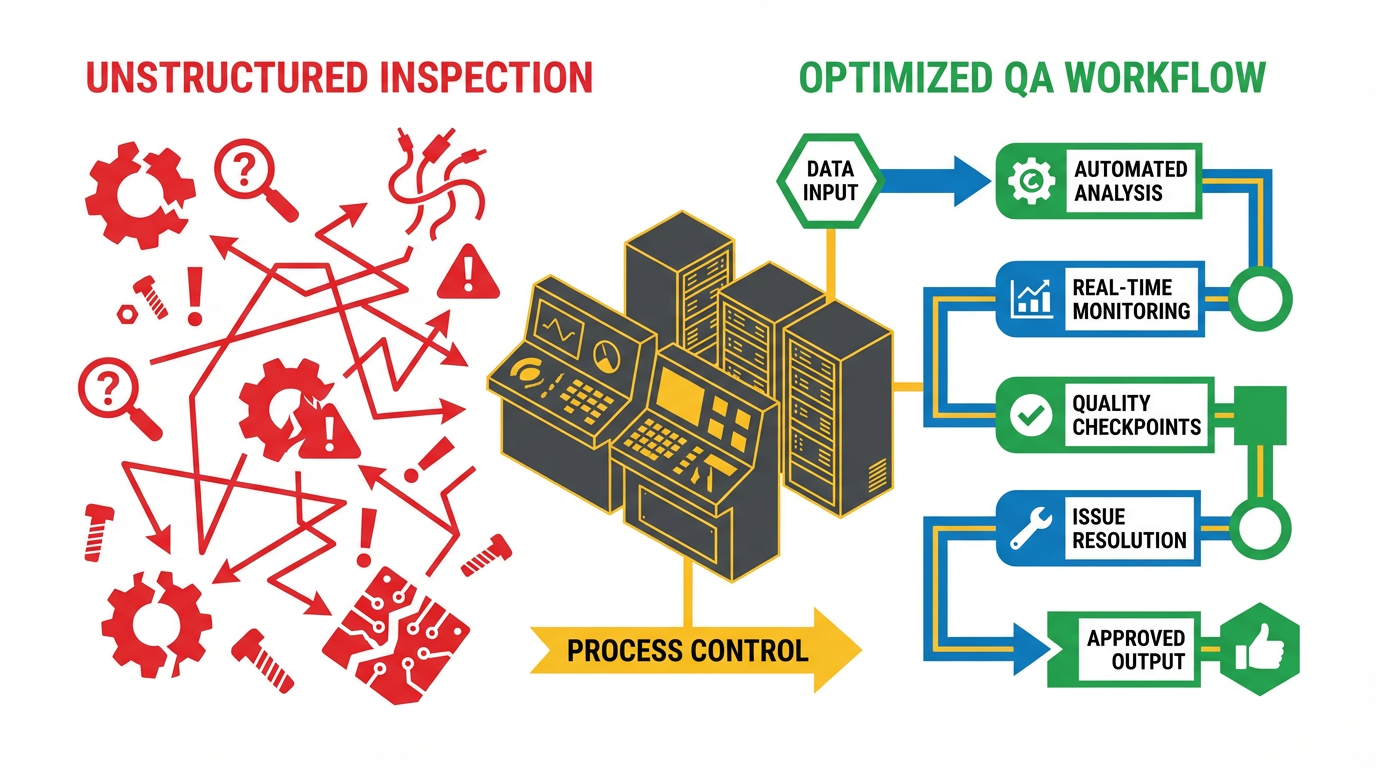

QA vs QC for Used Industrial Controls

A lot of confusion starts with terminology. Quality assurance and quality control are related, but they are not the same thing.

Industry guidance on manufacturing quality consistently defines quality assurance as a proactive, process‑focused discipline. QA is the system of standards, procedures, and governance that ensures you consistently design, build, refurbish, and integrate controls to a defined level of quality. It is about being “fit for purpose” and “right the first time,” not just catching defects afterward.

Quality control, by contrast, is reactive and product‑focused. QC is the inspections, tests, and measurements you perform on panels, PLCs, and assemblies to detect nonconformities before they go into service. Incoming inspection of used contactors, megger testing of insulation in a reused MCC bucket, loop checks after rewiring a panel—those are QC activities.

For used controls, robust QA means you have:

A documented process for evaluating whether a used component can even be considered, based on safety, environment, and standards impact.

Clear internal automation standards, aligned with ISA and ISO guidance, that define what “good” looks like for controllers, HMIs, wiring, and sensors.

A traceable way to show auditors how each reused item was assessed, tested, and approved.

QC then becomes one part of that QA system: specific electrical, functional, and software tests defined in advance, applied consistently, and recorded.

A simple way to think about it is that QA defines the rules of the game; QC is how you confirm each piece on the field actually obeys those rules.

External Standards That Shape “Acceptable” Used Controls

When you reuse controls, you are not operating in a vacuum. You are still expected to meet the same external standards that apply to new projects. Several standard families are particularly important.

Control Hardware and Panels

The IEC 61131 standard defines core hardware and software requirements for programmable controllers and standardizes PLC programming languages such as Ladder Diagram, Function Block Diagram, Structured Text, Instruction List, and Sequential Function Chart. If you are bringing in a used PLC, you need confidence that its hardware, firmware, and programming environment still align with this ecosystem, especially when you integrate it into a multi‑vendor plant.

For low‑voltage switchgear and controlgear assemblies, IEC 61439 is the modern reference. It covers design, assembly, and testing of control panels and MCCs, including temperature rise limits, dielectric properties, short‑circuit withstand, mechanical strength, and internal separation. If you reuse a control panel, your QA standard needs to address how you verify these aspects are still valid—or whether the original assembly never actually met them.

Electrical conductors and cabling are governed by standards such as IEC 60228 for conductor sizing, IEC 60331 for circuit integrity under fire, and IEC 60332 for flame‑spread characteristics. A used cabinet full of unmarked or unknown cables is more than a cosmetic problem; it is a question of whether those conductors still satisfy the assumptions your safety and fire protection strategies rely on.

In the US, NFPA 79 defines electrical requirements for industrial machinery, including wiring methods and protective measures. Automation practitioners point out that machines must comply with NFPA 79 to be legally connected to power. Reintroducing used hardware that compromises NFPA 79 compliance is asking for trouble with both safety and inspectors.

Functional Safety and Machine Safety

Functional safety in industrial control is anchored by IEC 61508, which defines lifecycle requirements and safety integrity levels for electrical, electronic, and programmable electronic safety functions. IEC 61511 adapts those principles to safety instrumented systems in the process industries. For machinery, IEC 62061 and ISO 13849 drive how safety‑related control functions are designed, validated, and assigned performance levels or safety integrity levels.

Machine safety specialists emphasize a simple but critical point: mixing components certified to different standards, or miscalculating equivalence between ISO 13849 performance levels and IEC 62061 safety integrity levels, can result in underperforming safety systems or failed audits. When you reuse a safety relay or safety PLC, you are walking directly into that territory.

Your QA for used controls must require a fresh look at the functional safety justification whenever you change:

The hardware used to perform a safety function.

The architecture of safety circuits or networks.

The operating context, such as cell layout or guarding.

Without that, you cannot honestly claim continued compliance with IEC 61508‑based expectations, IEC 62061, or ISO 13849.

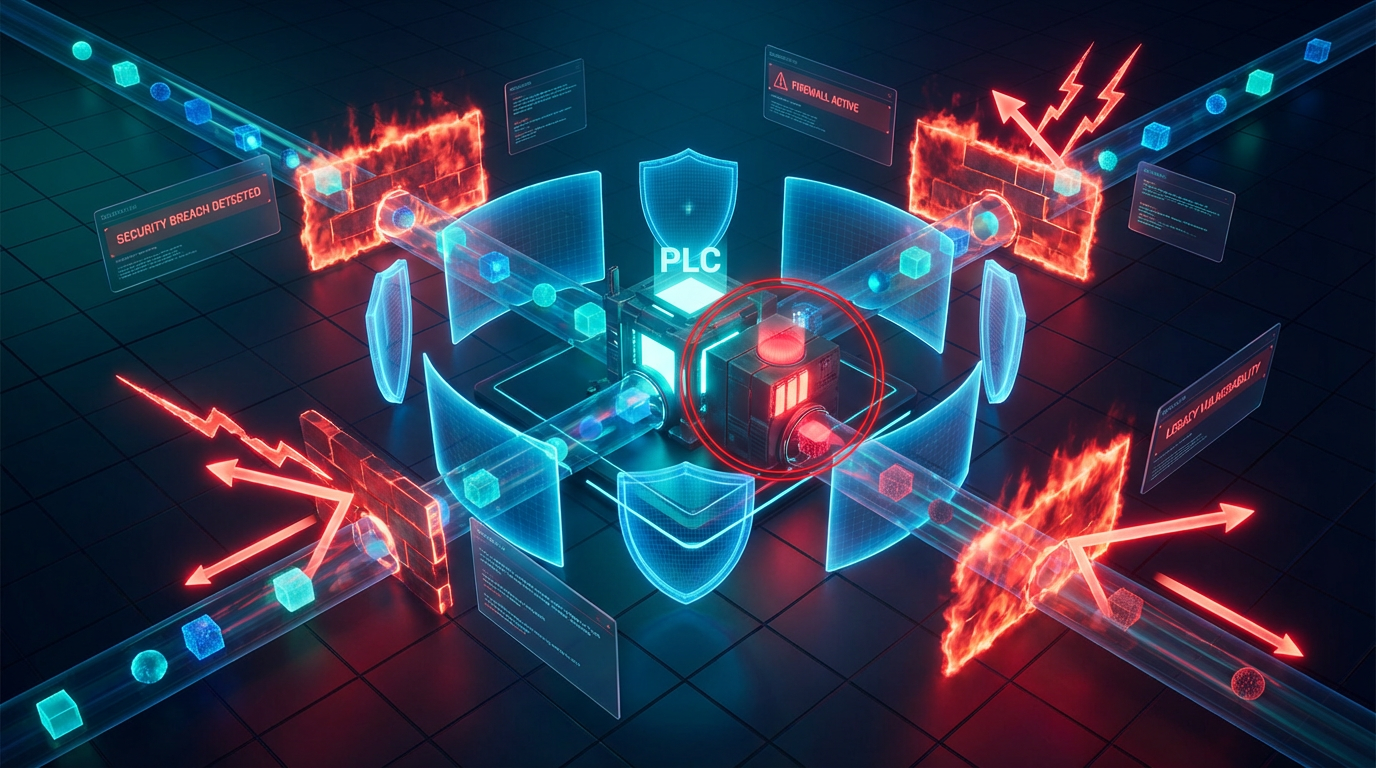

Cybersecurity and Networked Controls

Modern guidance on industrial cybersecurity comes from standards such as ISO/IEC 27001, ISA/IEC 62443, and NIST SP 800‑82. ISA/IEC 62443 in particular is recognized as a comprehensive baseline for securing industrial automation and control systems across sectors like utilities, pipelines, and petroleum production. It treats security as a lifecycle and risk‑management problem, defining security levels, zones, conduits, and technical requirements for both systems and components.

Used PLCs, remote I/O, or HMIs often come with unknown configuration histories, default passwords, or unsupported firmware versions. If you drop them into a network hardened according to 62443 principles without bringing them up to the same standard, you create weak links in what should be a consistent security architecture. QA for used controls therefore has to include cybersecurity checks, not just electrical tests.

Hazardous Areas and Special Environments

Where explosive atmospheres are involved, the IEC 60079 series is central. It covers equipment categories, temperature classes, and protection types such as explosion‑proof and intrinsically safe designs. Reusing instrumentation or enclosures in hazardous zones is not a purely mechanical question; you must be able to show that the equipment still meets its original explosion protection concept and that any modifications are compatible.

Alarm management and HMI behavior are guided by ISA 18 and IEC 62682, EEMUA 191, and ISA 101. These standards focus on alarm philosophy, prioritization, operator workload, and human‑centered display design. Bringing in a used HMI without reconciling its screens and alarms to your current alarm management strategy is another way to quietly erode compliance and operator effectiveness.

Summary Table: Standards Most Relevant to Used Controls

| Area | Key Standards and Guidance | Relevance to Used Controls |

|---|---|---|

| PLC and control software | IEC 61131; ISA and IEC controller guidance | Ensure reused PLCs and code conform to current expectations. |

| Panels and MCCs | IEC 61439; NFPA 79; IEC 60228/60331/60332 | Verify assembly integrity, wiring, and fire performance. |

| Functional safety | IEC 61508, IEC 61511, IEC 62061, ISO 13849 | Reassess safety functions when components are reused. |

| Cybersecurity | ISA/IEC 62443; ISO/IEC 27001; NIST SP 800‑82 | Eliminate inherited vulnerabilities from used devices. |

| Hazardous areas | IEC 60079 | Confirm explosion protection and marking remain valid. |

| Alarm and HMI design | ISA 18 / IEC 62682; EEMUA 191; ISA 101 | Align reused HMIs and alarm logic with current philosophy. |

This table is not exhaustive, but it illustrates how tightly used controls are tied to mainstream standards.

Your QA standards for reuse must explicitly reference the ones that apply in your domain.

Internal Automation Standards: The Backbone of QA for Used Controls

External standards set the boundary conditions. Day‑to‑day decisions about used controls are driven by your internal automation standards.

Control engineering guidance recommends that internal standards cover at least safety and electrical practices, HMI and operator interface design, controllers and I/O, and sensors and instruments. Those standards define preferred vendors, I/O levels (for example 24 Vdc versus 120 Vac), analog signal ranges such as 4–20 mA, environmental requirements for enclosures, human‑machine interface conventions, communication protocols like Ethernet/IP or Modbus TCP, and remote access rules.

When those internal standards exist, QA of used controls has something concrete to measure against. If a used panel contains non‑preferred PLC families, unsupported fieldbus protocols, or non‑standard sensor types, you can quantify the additional lifecycle cost and risk. If your HMI standard calls for certain screen sizes, color schemes, and navigation structures based on ISA 101 principles, you can decide whether an older operator terminal can be brought up to that level or should be replaced.

Without internal standards, decisions about reusing controls become subjective and inconsistent.

One site accepts a used panel as‑is, wiring color and all; another insists on rewiring to internal color codes; a third does something entirely different. That inconsistency is the enemy of long‑term maintainability and safety.

A Practical QA Workflow for Used Industrial Controls

Abstract standards are not enough. You need a repeatable workflow. The specifics will vary by industry, but a robust QA workflow for used controls generally includes several stages.

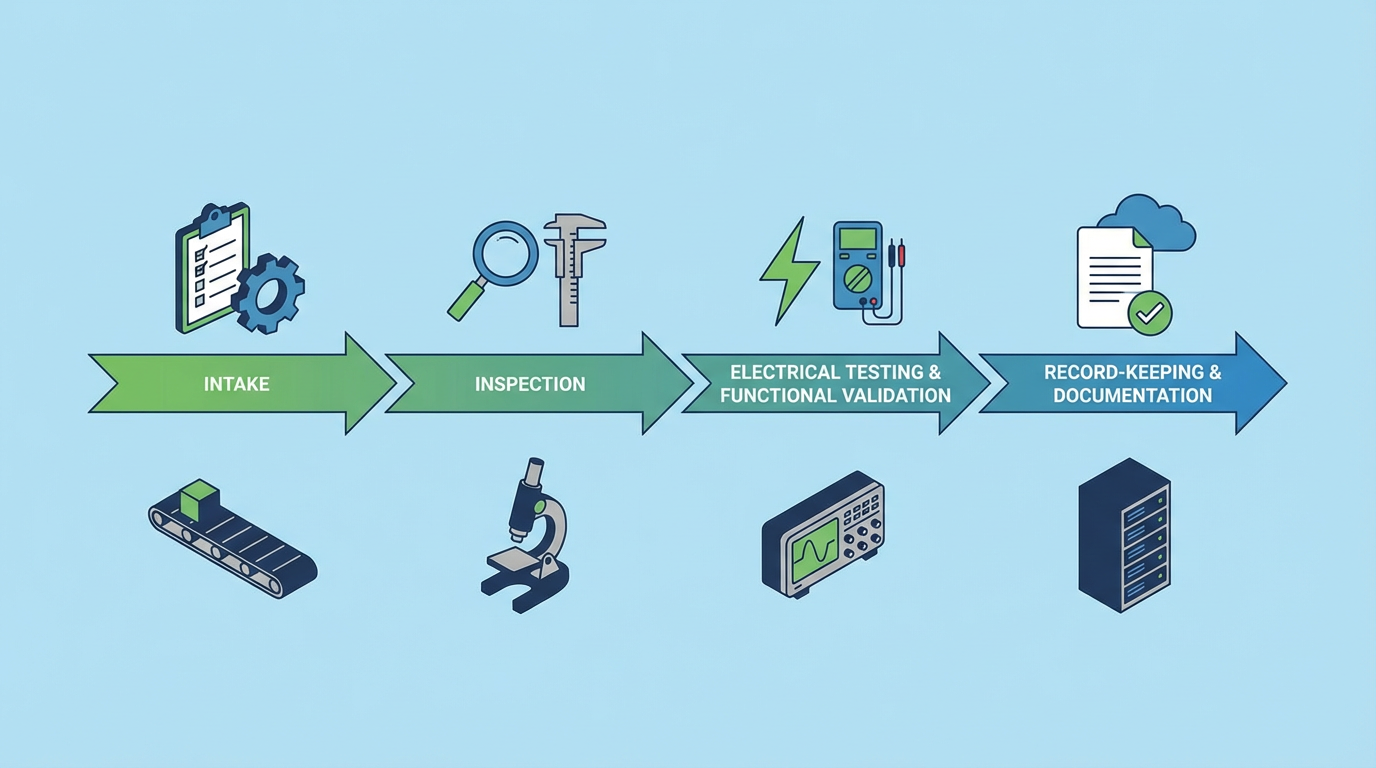

Intake, Traceability, and Risk Triage

QA starts the moment a used panel, PLC, or device arrives at your facility, not when you are desperate during a startup. Incoming quality control should log the item with a unique identifier, record its source, age if known, previous environment, and any available documentation. Traceability is essential; when a defect is found later, you need to know which lots or projects are affected.

From there, the QA process should categorize the item’s potential use. Components intended for safety‑related functions, hazardous areas, or high‑criticality processes belong in one category with stricter requirements. Less critical applications, such as non‑safety utility systems, may allow more flexibility. This is similar in spirit to the risk‑based thinking promoted in ISO 9001 and in public‑sector internal control guidance that distinguishes between control design and control operation.

In practice, many experienced integrators maintain a short list of scenarios where used controls are categorically disallowed, such as primary safety instrumented functions in high‑hazard processes or ignition‑capable equipment in explosive zones without fresh certification. Formalizing that list in QA policy prevents last‑minute compromises.

Technical Inspection and Testing

Once an item passes triage, technical inspection and testing begin. Industrial inspection guidance stresses inspection across stages, not just at final acceptance. For used controls, this includes:

Thorough visual inspection for heat damage, corrosion, cracked insulation, bent terminals, and unauthorized field modifications such as jumpers or bypassed interlocks.

Verification of nameplate data, ratings, and standards markings against the intended new application. For panels and MCCs, that includes assessing whether the assembly still reflects the design principles of IEC 61439 or relevant national codes.

Mechanical checks on enclosures, door seals, gland plates, and cable entries, especially where enclosure ratings such as NEMA 12 or higher are required by your internal HMI/IO enclosure standards.

Electrical testing, which can range from continuity and insulation resistance checks to more involved tests such as functional verification of interlocks, overloads, and protection devices.

Automated quality control technologies—machine vision, sensors, test racks—can accelerate and standardize this stage. Research on automated quality control in manufacturing shows that automated inspection can perform fast, consistent, real‑time checking of product characteristics and flag deviations. For used controls, that might mean automated test benches that cycle digital and analog I/O, validate relay actuation, or verify barcodes and labels on critical devices for traceability.

The key QA requirement is that test plans for reused equipment are defined in advance, repeatable, and documented, not reinvented for each project.

Functional Safety: Revalidating the Safety Lifecycle

Introducing used controls into safety‑related systems is not merely an economic choice; it is a change in the functional safety lifecycle. Functional safety practice in industrial automation is clear on this point: whenever you modify hardware, software, or operating conditions relevant to a safety function, you must revisit the hazard and risk assessment and the safety requirements specification.

Practitioners in machine safety outline a lifecycle that starts with hazard and risk assessment, moves through safety requirements, system design, implementation, verification and validation, operation and maintenance, and finally modification and decommissioning. Used safety components touch several of those phases at once.

In concrete terms, for each safety function affected by reused equipment, you should:

Confirm that the safety‑related control parts still meet the required performance level or safety integrity level determined by your original risk assessment, considering age, operating hours, and diagnostic coverage.

Revalidate the architecture against the relevant standard, such as ISO 13849 for safety‑related control parts or IEC 62061 for SIL‑based machinery control systems.

Update the safety requirements specification and loop or function documentation so that any future engineer or auditor can see exactly which component is doing what and on what basis it was accepted.

Experienced teams know that the biggest risk is misalignment between documentation and reality. Used hardware that “looks fine” but is not reflected correctly in the safety analysis can undermine an otherwise strong functional safety program.

Cybersecurity and Firmware Integrity

From a cybersecurity standpoint, a used PLC is an unknown. Standards like ISA/IEC 62443 emphasize that industrial automation security must be treated as a structured risk‑management problem, with defined security levels, zones and conduits, and component‑level requirements.

QA for used controls should therefore require, at minimum:

A clean baseline for firmware and configuration, ideally by reflashing from a trusted, vendor‑supplied image and removing any legacy project code or user accounts that you do not control.

Verification that the device’s firmware and hardware are still supported, especially for components that will sit in critical network zones. Unsupported devices are difficult to secure and patch.

Assessment of how the device will fit into your 62443‑style zoning model and whether additional controls—such as firewalls, access control, or intrusion detection—are needed to compensate for its limitations.

NIST SP 800‑82, which complements ISA/IEC 62443, points out that industrial components such as PLCs, RTUs, and SCADA nodes are attractive targets for attackers. Reusing such equipment without a cybersecurity lens is no longer acceptable practice in energy, chemical, or critical infrastructure sectors.

Documentation, Internal Control, and Evidence

A quality assurance program for used controls lives or dies by its documentation. International guidance on internal control systems stresses the need for clear process mapping, risk assessment, evidence gathering, and follow‑up.

In the context of used controls, your QA documentation should show:

How the decision to reuse a component was made, including the applicable internal standards and external requirements.

What inspections, tests, and safety analyses were performed, with traceable results.

What changes were made to wiring diagrams, P&IDs, cause‑and‑effect charts, and PLC or safety logic.

Compliance and quality automation tools can help here. Research on compliance automation shows how automated evidence collection, control mapping, and reporting can centralize data that would otherwise be scattered across spreadsheets and email. For used controls, integrating your QA workflow into such tools allows you to automatically link test results, photos, and configuration snapshots to specific devices and projects, making audits and incident investigations far more efficient.

Pros and Cons of Relying on Used Controls

Not every project can or should use used hardware, even with strong QA. It helps to be explicit about the trade‑offs.

On the positive side, used and refurbished controls can shorten lead times dramatically when global supply chains are tight. They can reduce capital cost on brownfield upgrades where budgets are constrained and can support sustainability goals by extending the life of still‑capable equipment. If your QA standards are rigorous, the operational risk can be managed to an acceptable level.

On the negative side, used controls come with inherent uncertainty. You rarely have perfect knowledge of service history, environmental exposure, or prior faults. Standards evolve; a panel that was perfectly adequate under an older edition of a code may not satisfy current requirements. Cybersecurity expectations have risen sharply, and many older devices lack features you now consider baseline. In functional safety, even small undocumented modifications can invalidate prior safety justifications.

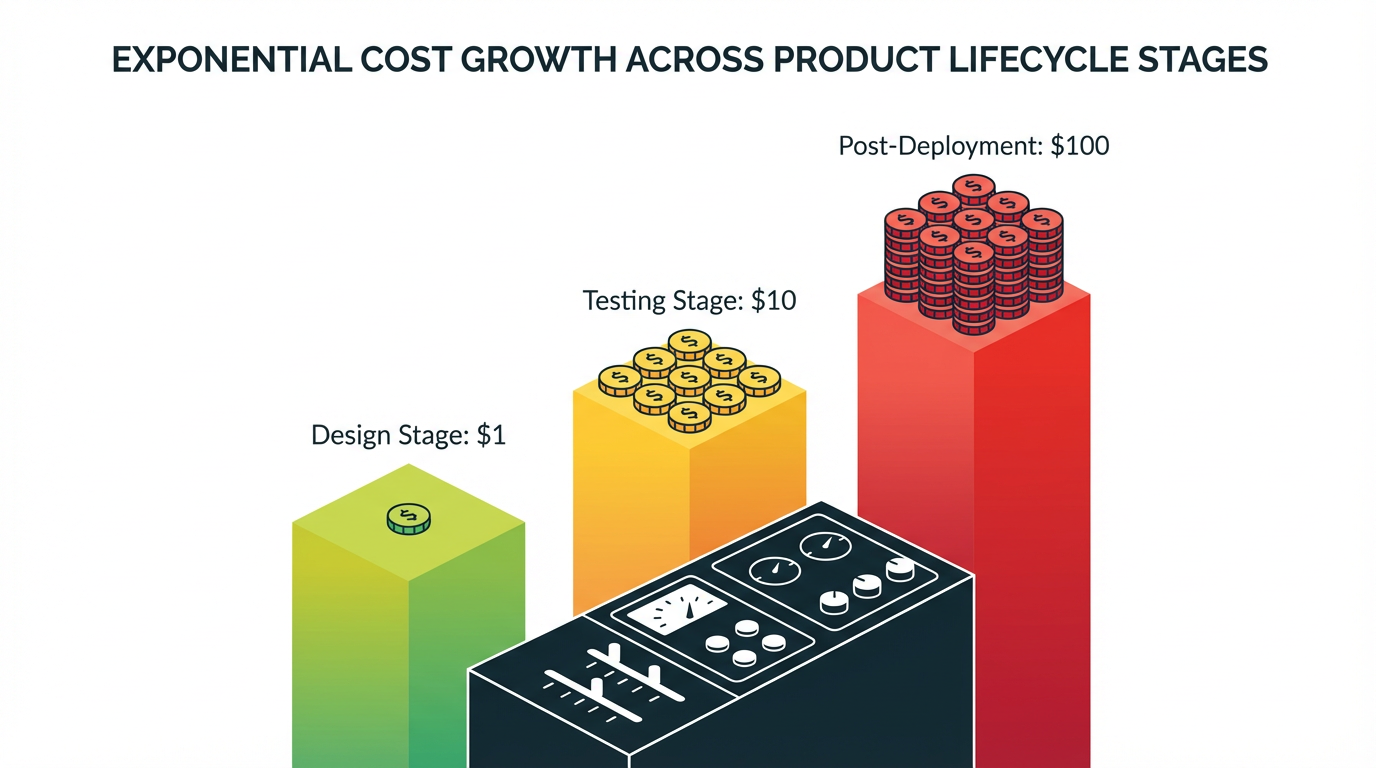

From a business perspective, quality studies note that correcting defects late in the lifecycle can cost an order of magnitude more than catching them early, and exponentially more once issues reach customers or regulators. That 1:10:100 pattern is as true for industrial controls as it is for consumer products.

A used control panel that fails during a factory acceptance test is an annoyance; the same panel failing after startup under load can be very expensive.

The conclusion many veteran integrators reach is this: used controls are acceptable for high‑volume, low‑risk applications, and for carefully selected roles in more critical systems, but only when governed by explicit QA and internal standards. Otherwise, what you save on hardware you pay back many times over in downtime, rework, and lost trust.

How Automation Strengthens QA for Used Controls

There is a parallel between the evolution of QA automation in software and manufacturing and what we need for used industrial controls. Articles on QA automation, automated quality control, and inspection emphasize that manual, checklist‑driven processes struggle to keep up with complexity and volume. Automation does not replace engineering judgment, but it does make rigorous QA economically feasible.

Automating Testing and Inspection

Automated quality control systems—using sensors, high‑resolution cameras, and AI—are widely deployed in manufacturing to perform fast, consistent inspections. In the context of used controls, similar techniques can be applied to:

Automated I/O exercising for used PLC racks and remote I/O, with pass/fail criteria and logged results.

Machine vision inspection of control panels to verify presence and position of devices, label legibility, and absence of obvious damage.

Automated measurement of key electrical parameters such as contact resistance or insulation resistance, using predefined test profiles and limits.

The benefit is not only speed but repeatability. Automation applies the same criteria every time, without fatigue or subjectivity, which is especially important when you are handling larger volumes of used equipment.

Research on automated proofreading and content control in regulated industries shows that automated systems can cut inspection time roughly in half while improving error detection, particularly on labels and documentation. Similar gains are achievable when you automate parts of the QA process for control documentation, checking that wiring diagrams, loop sheets, and PLC tag lists line up after a reuse project.

Automating Compliance and Evidence Management

Compliance automation platforms demonstrate how tasks such as evidence collection, control mapping, risk assessment, and reporting can be automated and centralized. For used industrial controls, automating QA‑related compliance tasks can include:

Pulling configuration data, firmware versions, and diagnostic logs from networked devices at defined intervals and storing them in a central repository as evidence of ongoing QA.

Mapping internal automation standards and external requirements (for example IEC 61439, IEC 61511, ISA/IEC 62443) to specific controls and projects, and tracking whether reused equipment satisfies or conflicts with those mappings.

Generating real‑time dashboards that show where reused hardware is deployed, what tests have been performed, and where gaps exist.

Surveys of compliance professionals cited in research show that a majority believe automating manual processes significantly reduces the complexity and cost of compliance. In my experience, this is equally true when you apply it to the niche of used control QA. Instead of chasing PDFs and spreadsheets, your QA and engineering teams can focus on technical decisions.

Automation does not absolve you of responsibility. Human oversight remains essential to interpret alerts, tune rules, and respond to evolving standards. But it makes a rigorous QA standard for used controls achievable at scale.

When to Draw the Line and Reject Used Controls

A mature QA standard does not only describe how to accept used controls; it clearly defines when to say no.

Typical non‑negotiables for many plants and integrators include:

Safety‑instrumented functions where you cannot reconstruct a defensible safety lifecycle with used components, aligned with IEC 61508 and IEC 61511 or their machinery equivalents.

Hazardous area equipment whose certification status cannot be verified or has been compromised by modifications, relative to IEC 60079 expectations.

Control panels so far from current IEC 61439, NFPA 79, or internal standards that refurbishment would cost more than replacement.

Legacy networked devices that cannot be secured to the level expected by ISA/IEC 62443 and NIST SP 800‑82, especially in critical zones.

These decisions should be codified in your QA standard, not left to case‑by‑case negotiation under schedule pressure. The most reliable partners I have worked with—on both owner and integrator sides—are those who can explain, calmly and with references, why they refused to reuse a seemingly “perfectly good” cabinet in a particular application.

A Veteran Integrator’s Closing Advice

Used industrial controls are neither inherently bad nor inherently good. They are simply higher‑variance assets. The only way to make them dependable is to wrap them in a disciplined quality assurance framework that ties together external standards, internal automation rules, risk assessment, inspection, functional safety, and cybersecurity.

If you treat used controls as a shortcut around standards, they will eventually cost you more than they save. If you treat them as another input to a robust QA process—aligned with IEC and ISA guidance, backed by ISO‑style quality management, and supported by smart automation—they can be a legitimate tool in your project strategy.

As a systems integrator and long‑term project partner, my rule is straightforward: document the standard you will apply to used controls, test to that standard every time, and be prepared to walk away from reuse when the evidence is not there. That discipline is what protects your people, your plant, and your reputation.

References

- https://www.isa.org/standards-and-publications/isa-standards

- https://www.nema.org/standards/view/industrial-control-and-systems-general-requirements

- https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2019/06/guidelines-for-assessing-the-quality-of-internal-control-systems_a14f705d/2a38a1d9-en.pdf

- https://www.arcweb.com/industry-best-practices/importance-industry-standards-regards-comprehensive-automation-strategy

- https://support.automationdirect.com/docs/controlsystemdesign.pdf

- https://automationforum.co/30-international-standards-for-control-systems-the-complete-guide-for-automation-instrumentation-engineer/

- https://callcriteria.com/quality-assurance-automation/

- https://www.controleng.com/setting-internal-automation-standards/

- https://www.globalvision.co/blog/an-introduction-to-automated-quality-control

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/key-isa-iec-standards-every-automation-engineer-should-zohaib-jahan-pesyf

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment