-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Evaluating Surplus Automation Parts Reliability: A Veteran Integrator’s Guide

Surplus and obsolete automation parts used to be something you tripped over on the way to the real project. Today, with long lead times, tariffs, and constant end‑of‑life announcements, surplus parts are often the only way to keep a legacy line running or launch capacity quickly without blowing the capital budget. The question is no longer whether you will use surplus automation hardware, but whether you can trust it.

As a systems integrator, I have seen both sides. I have watched plants save hundreds of thousands of dollars and weeks of downtime by commissioning surplus drives, PLCs, and HMIs that were tested and documented properly. I have also seen production managers gamble on cheap, unverified surplus hardware and pay for it with cascading failures and overtime that erased any savings. The difference is the reliability discipline you apply before and after you buy.

This article lays out a pragmatic approach to evaluating surplus automation parts reliability, grounded in what reputable sources are doing in practice: acceptance criteria from ATS Industrial Automation, obsolescence and sourcing guidance from Industrial Automation Co., obsolescence planning from NW Industrial Sales and PLC Automation Group, quality control principles from Pacific IC, surplus strategies from United Industries, GreenBidz and others, and predictive maintenance and spares management practices from Umbrex and reliability engineering research.

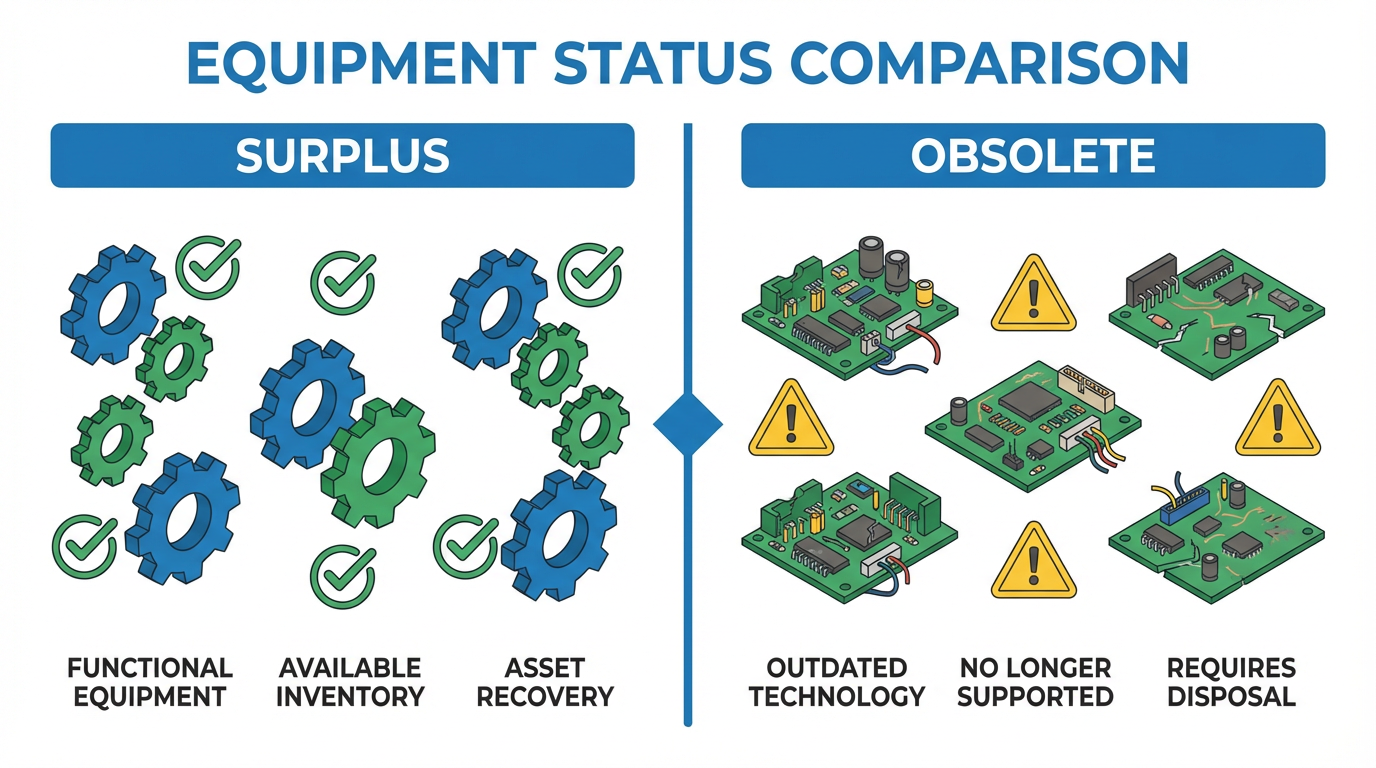

Surplus, Obsolete, and “Still Reliable”: Definitions That Matter

Surplus equipment is not necessarily junk. GreenBidz describes surplus equipment as still‑functional industrial assets from plants that have closed, relocated, or upgraded. United Industries similarly notes that surplus inventory often consists of backup motors, spare transformers, and even full production lines that became idle after technology upgrades or project changes. In other words, “surplus” generally describes commercial status, not technical condition.

Obsolete automation parts are a different issue. Industrial Automation Co. and PLC Automation Group define obsolete parts as components that OEMs no longer make or fully support. Think legacy PLC CPUs, older variable‑frequency drives, or discontinued HMIs that are still essential to installed equipment. NW Industrial Sales further clarifies obsolescence into four types: technological (superseded technology), functional (no longer meets operational needs), legal (no longer compliant with regulations), and economic (no longer cost‑effective versus alternatives).

From a reliability standpoint, the important nuance is that a part can be surplus without being obsolete, and obsolete without being unreliable. The risk comes when you conflate the labels and assume that surplus automatically means risky or, worse, that any obsolete part that powers up is “good enough.” The job is to separate commercial status from technical reliability.

Why Surplus Reliability Is a Business Decision, Not Just a Maintenance Call

Unplanned downtime is one of the most expensive lines on a hidden profit‑and‑loss statement. Industrial Automation Co. cites unplanned manufacturing downtime at roughly $5,600 per minute in many operations, and the impact escalates sharply when the affected line is critical. That figure includes lost production, idle labor, and missed customer commitments, yet many plants under‑account for it because downtime cost rarely shows up as a neat budget number.

At the same time, new automation hardware is more expensive and harder to get. Industrial Automation Co. notes that tariffs on foreign‑made automation parts have pushed prices up by roughly 30 to 145 percent in some categories, while supply chain issues have extended OEM lead times for common modules and drives to about ten to sixteen weeks. United Industries observes that unused equipment loses 20 to 30 percent of its value in the first year as technology advances, while storage and maintenance add carrying costs on the order of 15 to 25 percent of equipment value annually.

Against that backdrop, surplus and refurbished equipment look attractive. GreenBidz reports that buying secondhand production equipment typically cuts capital cost about 30 to 70 percent versus new. TBS‑Swiss notes that used production machines can reduce investment costs by up to 50 percent, and United Industries shows that selling surplus often recovers 40 to 70 percent of original investment while freeing space and reducing insurance and storage costs. The financial logic is clear, but it is only valid if the reliability of the surplus parts is good enough that they do not create more downtime than they prevent.

That is why evaluating surplus reliability is not just a technical inspection.

It is part of a broader risk and asset strategy that has to balance downtime cost, capital cost, and lifecycle support.

What Reliability Looks Like for Surplus Automation Parts

When you strip away labels, surplus automation hardware is just another reliability question: will this asset function effectively, safely, and affordably over the period you need it. Manufacturing Digital frames reliability as a combination of availability and performance over the asset’s useful life, and that logic applies equally to surplus components.

Technical fitness and obsolescence risk

NW Industrial Sales warns that continuing to operate with obsolete parts can dramatically increase maintenance, repair, and replacement costs, and extend downtime while you hunt for technicians or parts. PLC Automation Group reinforces that obsolete parts often create compatibility issues because modern components are rarely drop‑in replacements, forcing engineering work and custom solutions that can introduce new failure modes.

This means a technically “working” surplus part can still be a poor reliability choice if it is technologically obsolete, functionally marginal, legally non‑compliant, or economically unsound. A used drive or PLC from a current family with strong ongoing support and compatible firmware is fundamentally different, from a reliability risk perspective, than an obscure controller with no documentation and no modern equivalent.

Supportability and lifecycle position

Industrial Automation Co. notes that many PLCs have a typical support window of about ten to fifteen years before parts and service become scarce. NW Industrial Sales recommends that a solid obsolescence plan explicitly track how machinery is running, what needs fixing when, and which parts will be required, backed by access to technicians who understand those assets.

When you evaluate surplus parts, you are really placing a bet on where in the lifecycle they sit. A surplus drive that is only a few years into that support window, well documented, and widely deployed may be a sound choice for a critical asset. The same drive near the end of its lifecycle, with no EOL replacement path, might be a better fit for non‑critical backups or training rigs.

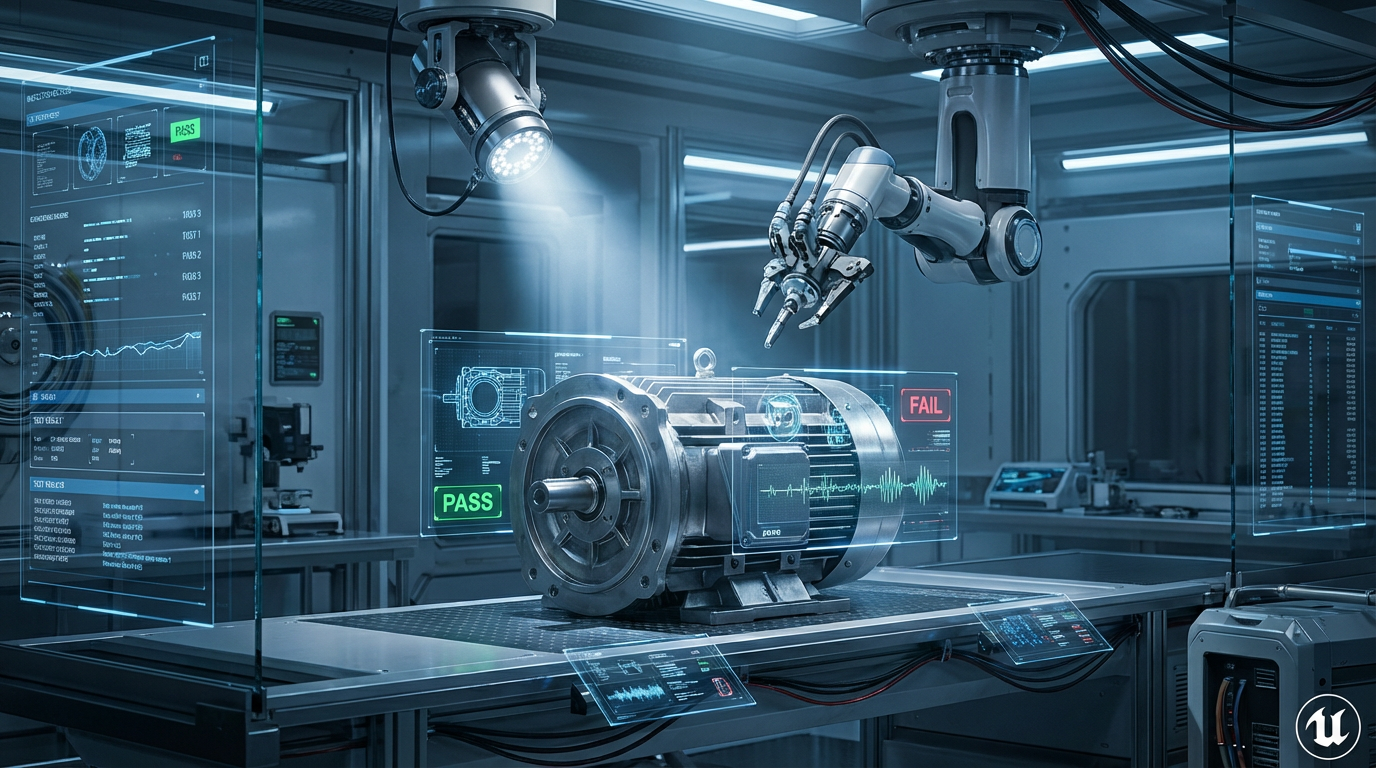

Evidence: testing, quality control, and warranties

Pacific IC defines quality control in industrial parts supply as systematic processes that monitor and evaluate consistency, performance, and safety from raw materials through final inspection. They emphasize supplier audits, structured KPIs such as defect rates and on‑time delivery, and product testing under temperature extremes, humidity, vibration, mechanical stress, and other conditions.

Industrial Automation Co. recommends insisting on robust testing and warranties for obsolete and surplus parts, highlighting multi‑point functional testing and warranties up to twenty‑four months on refurbished brands like ABB, Mitsubishi, and Allen‑Bradley. They advise asking suppliers for specifics on test procedures, including continuity checks, load tests, and real‑world simulation, as well as case studies or references to confirm actual performance.

In reliability terms, surplus parts are only as trustworthy as the evidence you have.

That evidence comes from how the supplier controls quality, how thoroughly the part has been tested under relevant conditions, and what warranty backs it.

The table below summarizes the main evidence levers that matter most for surplus reliability.

| Evidence Source | What to Look For | Why It Matters for Surplus Reliability |

|---|---|---|

| Supplier quality system | Documented QC processes, ISO‑aligned practices, low defect and return rates | Indicates that incoming, refurbishment, and shipping stages are controlled |

| Functional testing reports | Multi‑point tests under load, including I/O, communications, and protections | Shows that the specific unit has performed correctly under realistic stress |

| Environmental history | Storage conditions, maintenance records, runtime hours | Differentiates climate‑controlled spares from units that sat outdoors |

| Warranty terms | Length and scope of coverage, exclusions, response time | Transfers part of the failure risk back to the supplier |

| Field performance data | Case studies, user references, repeat orders for similar parts | Gives real‑world evidence beyond test benches |

A Practical Evaluation Process for Surplus Automation Parts

In practice, evaluating surplus automation parts is not one heroic inspection; it is a chain of decisions. The plants that get this right tend to follow a consistent process that ties obsolescence planning, supplier vetting, testing, and integration together.

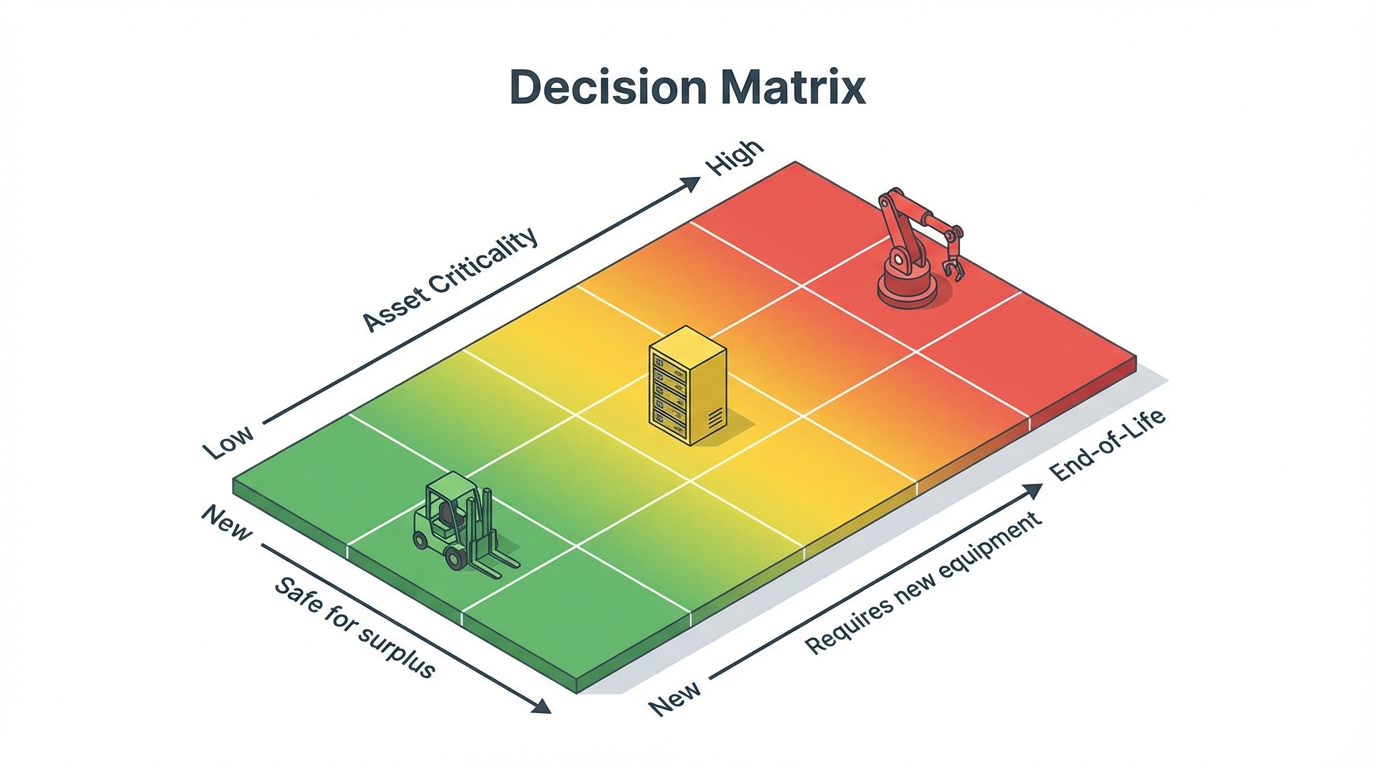

Map critical assets and failure risk

Augury, writing on critical manufacturing assets, argues for an asset criticality assessment that scores each machine by the impact of its failure. Critical assets are those whose failure would shut down the production line, and they deserve focused spending on sensors, maintenance, and spares. Non‑critical assets can fail without halting operations and do not justify the same investment.

Industrial Automation Co. advises plants to audit their entire production line and build a detailed asset inventory that includes part and serial numbers, firmware, installation dates, maintenance history, and expected lifespan. NW Industrial Sales recommends combining that visibility with an explicit obsolescence plan that identifies which machines and components are at risk and assigns a team to track their condition and produce risk analyses.

When you overlay asset criticality, lifecycle position, and obsolescence status, you get a map that tells you where surplus parts can safely play and where you need either new equipment or fully characterized refurbished hardware with strong support.

Pre‑screen suppliers and lots, not just individual parts

United Industries notes that many manufacturers are unknowingly sitting on tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars in recoverable surplus value, but that value is only realized if someone does the “surplus detective work” of walking the facility and documenting what is there, its specs, condition, and market value. WeSellStocks similarly emphasizes structured inventory assessment, cataloging each surplus item with model, manufacturer, condition, and market demand before deciding whether to resell, refurbish, or repurpose.

From the buyer’s perspective, that same discipline should be mirrored upstream. Pacific IC recommends supplier audits and ongoing performance monitoring using KPIs such as defect rates and regulatory compliance records. Industrial Automation Co. suggests looking for suppliers with global sourcing networks, knowledge of standards like ISO 9001 and UL, and the ability to provide engineering support and cross‑references to modern equivalents.

When you evaluate surplus parts reliability, you should ask not only whether an individual drive or PLC looks clean, but whether the platform selling it treats surplus inventory as an engineered product with traceability, QC, and test data, or as anonymous scrap.

Functional testing and acceptance criteria

ATS Industrial Automation makes a strong case that clear acceptance criteria act as a scorecard for automated equipment. They use metrics such as cycle time, number of faults, and machine availability to confirm that a machine does what it was designed to do. They also warn that poorly defined objectives and milestones account for a large share of project failures, citing Project Management Institute research attributing roughly thirty‑seven percent of project failures to poorly defined objectives and about thirty percent to poor communication.

The same logic applies to surplus parts. Instead of treating a refurbished drive or PLC as “tested OK,” define acceptance criteria for that component. For a drive, that might include ramping through its power range under load, verifying protection trips, and checking that it communicates properly with your PLC family. For a PLC CPU, it might mean loading a standard test program, exercising digital and analog I/O, verifying communication ports, and cycling power repeatedly while monitoring for faults.

The RealPars guidance on Factory Acceptance Tests for PLC control panels gives a useful blueprint. They recommend powering panels safely, energizing internal devices, and then systematically testing each digital and analog I/O channel, using signal simulators where appropriate, and confirming that the PLC logic and HMI indications respond as expected. Industrial Automation Co. stresses that good repair services should perform full functional testing under realistic load and back their work with warranties.

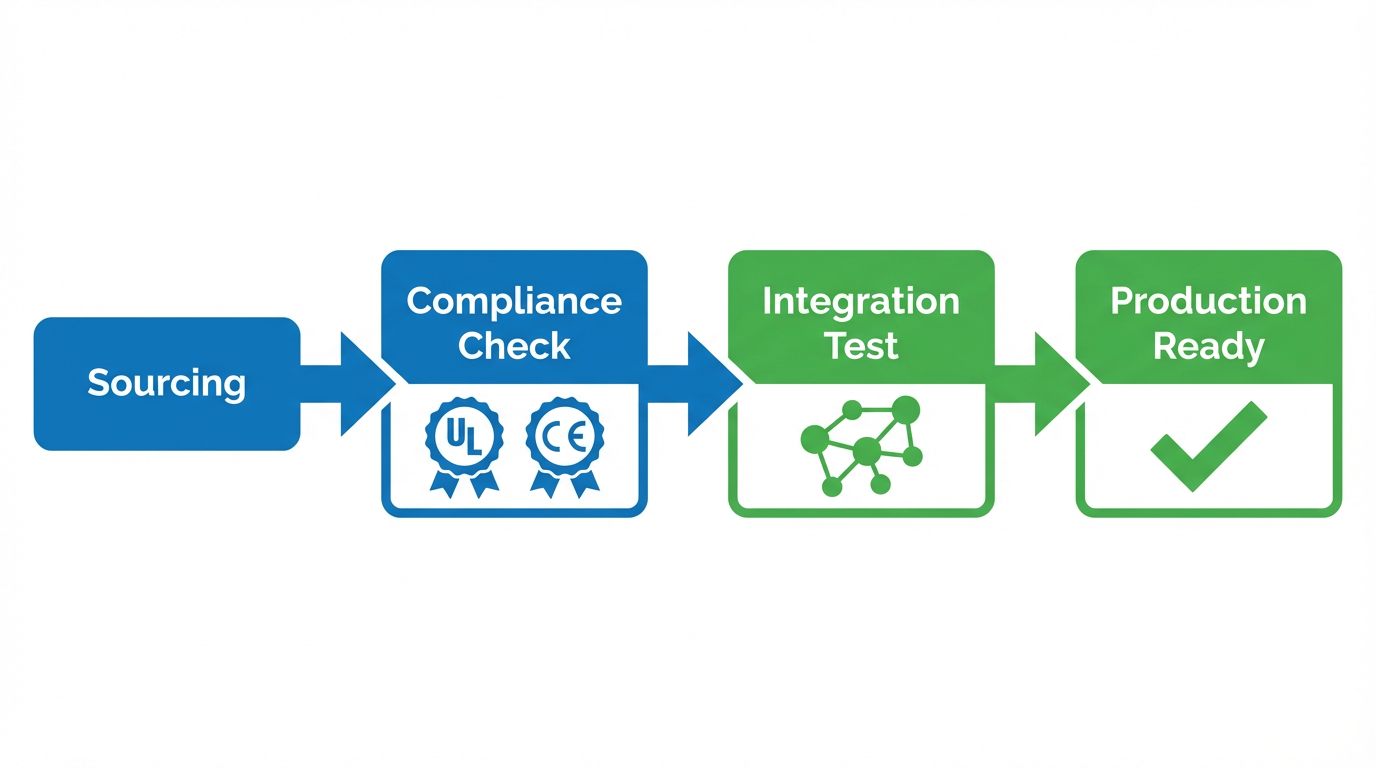

For surplus components, a lightweight but disciplined “mini‑FAT” on the bench before the part is declared production ready can catch miswired terminals, marginal power supplies, failing fans, and firmware compatibility issues that visual inspection will not reveal. Viewpoint USA notes from experience that even relatively simple test automation, such as automated instrument control and logging, can dramatically reduce test time while improving detection of subtle functional issues.

Integration, compliance, and safety

TBS‑Swiss highlights that the main risks when buying used machines include hidden defects, outdated control technology, and limited compatibility with existing or digitalized production environments. They emphasize the importance of checking the control system’s currency, degree of automation, connectivity, and ability to integrate into Industry 4.0 environments, along with retrofit potential for modern sensors and control software.

United Industries reminds us that reliability is also environmental. They show that facilities that invest in proper environmental protection for equipment see about forty percent fewer maintenance issues and around twenty‑five percent longer equipment lifespan. They also stress proper matching of voltage and amperage, recognition of continuous versus intermittent loads, and verification of safety certifications such as UL, CE, CSA, and IEEE standards.

Pacific IC underlines that compliance testing for safety, environmental performance, and electromagnetic compatibility is part of reliability, not an optional extra. NW Industrial Sales notes that legal obsolescence driven by new regulations can force the retirement of otherwise functional equipment.

For surplus parts, that means you should treat integration and compliance as part of the reliability evaluation.

A surplus drive without the right safety certifications, or a controller that cannot be brought into compliance with current safety requirements, may introduce reliability risk in the form of future forced replacements or restrictions by insurers and regulators.

Pros and Cons of Surplus Automation Parts for Reliability

Surplus and refurbished automation parts make sense in many scenarios, but they come with their own reliability profile. The tradeoffs are easier to see side by side.

| Aspect | Reliability Advantages | Reliability Risks or Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Capital cost and availability | GreenBidz and TBS‑Swiss report 30–70 percent savings versus new and faster access | Cheaper parts can tempt shortcuts on testing and documentation |

| Lead time and uptime | Industrial Automation Co. notes long OEM lead times; surplus can ship immediately | Relying on a single surplus unit with unknown history can create new bottlenecks |

| Lifecycle and obsolescence | NW Industrial Sales and PLC Automation Group show surplus helps bridge obsolescence windows | Technologically or legally obsolete parts may lock you into fragile architectures |

| Quality and testing | Industrial Automation Co. demonstrates that tested, warranted surplus can meet or exceed OEM performance | Pacific IC warns that weak QC and testing can lead to higher defect and failure rates |

| Sustainability and waste | United Industries and NW Industrial Sales show surplus reuse can cut waste 30–50 percent | Poorly controlled reuse can propagate unsafe or non‑compliant equipment |

The key point is that surplus parts are not inherently unreliable.

The reliability profile is defined by how you select, test, integrate, and monitor them.

Backstopping Surplus with Data, Predictive Maintenance, and Spares Strategy

Even a carefully tested surplus part is still a used asset. To keep risk under control, you should surround it with data and sound spare‑parts management.

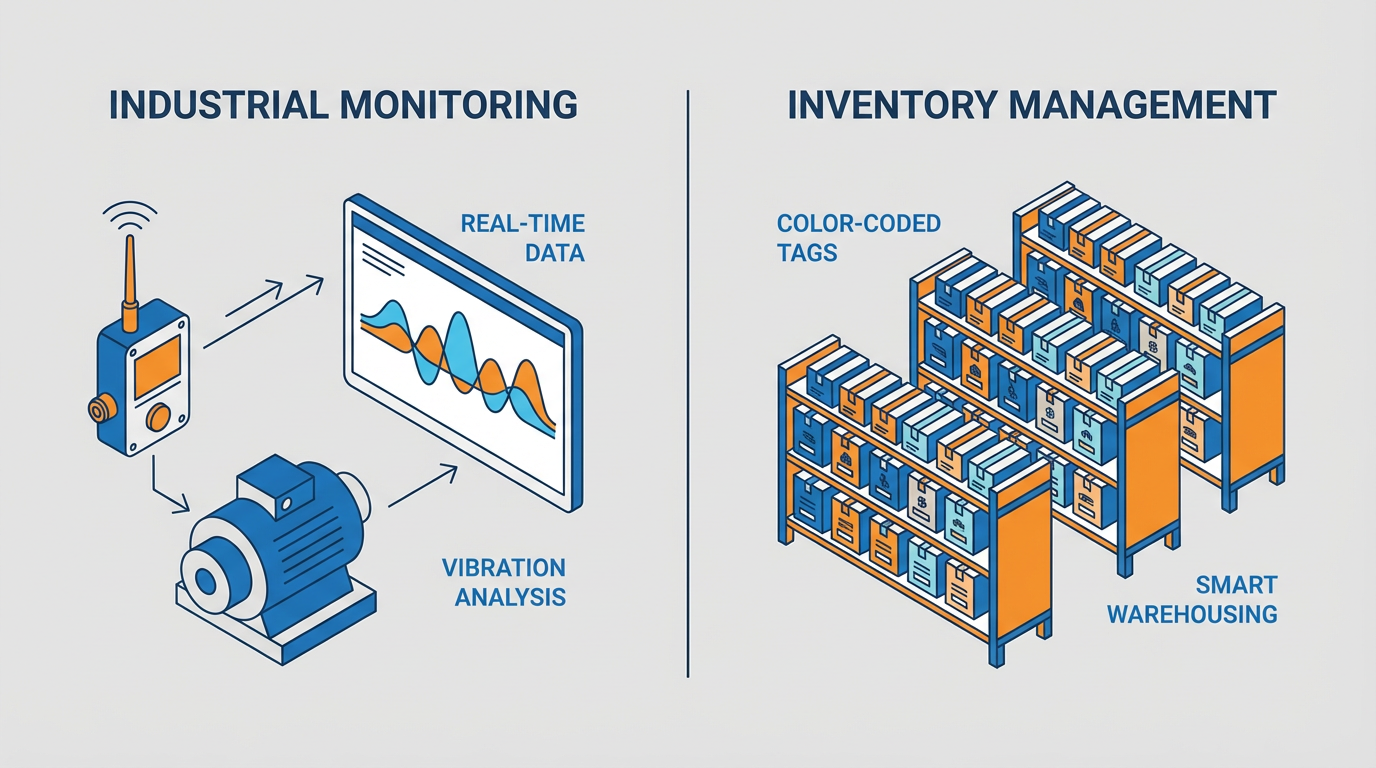

Manufacturing Digital emphasizes that modern automation systems generate rich operational and maintenance data that feed reliability engineering tools such as root cause analysis and failure mode and effects analysis. Predictive maintenance, supported by sensors and Internet‑connected systems, allows teams to detect anomalies early and prevent unplanned breakdowns. Umbrex adds that predictive maintenance systems use real‑time sensor data on vibration, temperature, pressure, and other metrics to forecast failures and enable proactive interventions.

Umbrex also describes a structured approach to spare‑parts management that begins with assessing current inventory and usage trends, classifying parts by criticality, and setting reorder points and safety stock levels based on usage rates, lead times, and stockout risk. They recommend integrating predictive maintenance with Computerized Maintenance Management Systems or ERP systems so that condition data drives spare‑parts decisions automatically.

Augury warns against panic‑buying spare parts as a hedge against disruption, because that inflates inventory and overhead without necessarily improving uptime. Instead, they advocate tying parts inventory to asset criticality scores and condition monitoring, so that you stock what you need for critical assets and avoid hoarding spares for non‑critical equipment.

For surplus parts, this means two things.

First, once a surplus component is in service, treat it as a monitored asset, not as a “black box” you hope will last. If predictive systems indicate rising failure risk, Umbrex’s guidance suggests adjusting safety stock or accelerating replacement plans. Second, build your surplus strategy into the spares framework: decide where surplus parts will serve as primary spares, where they are only acceptable as last‑resort backups, and where obsolescence risk is high enough that new hardware and retrofits are the better route.

When Surplus Is the Smart Move – And When It Is Not

There is no universal rule that “surplus is fine” or “surplus is dangerous.” The right answer depends on criticality, lifecycle, and the quality of the surplus channel.

Surplus shines when you have legacy equipment that is still fit for purpose but no longer fully supported, and when the downtime cost and lead times for new hardware are high. PLC Automation Group notes that obsolete parts can be kept in service safely if you combine stockpiling, targeted upgrades, and relationships with specialized suppliers. Industrial Automation Co. describes using pre‑tested backup units on‑site as a way to turn what would be a full line stoppage into a short maintenance window. United Industries and GreenBidz both show how surplus equipment can quickly add capacity or provide backups during demand spikes and supply chain disruptions, with strong circular‑economy benefits.

On the other hand, Industrial Automation Co. explains that replacement is generally the better option when a component is mission‑critical, has failed multiple times despite repairs, or when repair costs exceed roughly half the price of a new or surplus unit. Obsolescence is also a key replacement trigger, especially when you are upgrading to modern communication protocols and need enhanced diagnostics and remote access that older hardware cannot provide. NW Industrial Sales reminds us that legal and safety changes can also push you toward replacement even if hardware still works.

In practical terms, surplus parts are an excellent tactical tool for bridging gaps, supporting legacy assets with remaining useful life, and stretching capital during expansion. They are a weak tool for masking systemic obsolescence in critical systems where one failure can shut down the plant and where the regulatory or technology landscape has moved on.

Short FAQ on Surplus Automation Parts Reliability

How do you decide if a surplus automation part is reliable enough for a critical asset?

Start by scoring the asset’s criticality as Augury suggests, and quantify downtime cost using your own data and the kind of benchmarks Industrial Automation Co. cites. Then assess the surplus part’s lifecycle position, obsolescence status, and supportability as described by NW Industrial Sales and PLC Automation Group. Finally, demand objective evidence from the supplier: documented multi‑point testing, clear quality control practices, and warranties of the kind Industrial Automation Co. outlines. If all three align in your favor, surplus can be a defensible choice even for critical assets.

Are refurbished and surplus parts always less reliable than new ones?

Not necessarily. Pacific IC points out that reliability hinges on quality control and testing, not just age. Industrial Automation Co. notes that refurbished parts that undergo rigorous functional testing under realistic load and carry strong warranties can meet or exceed OEM performance expectations. Conversely, a new part with poor handling or inadequate testing can fail early. The key is the process behind the hardware.

How should surplus fit into an obsolescence and spares plan?

NW Industrial Sales and PLC Automation Group frame obsolescence as a manageable lifecycle issue if you plan ahead. Umbrex shows that predictive maintenance and structured spares management can keep inventory optimized. Surplus fits into that picture as one of several tools: you can stock surplus spares for high‑risk obsolete components, use surplus equipment to extend the life of debt‑free but otherwise sound lines, and convert your own surplus into cash that funds upgrades. The point is to plan the role of surplus explicitly instead of treating it as an opportunistic afterthought.

Closing Thoughts

Reliable surplus automation parts are not a myth; they are the result of disciplined selection, testing, and lifecycle planning. The plants that win with surplus are not the ones that find the cheapest used drive, but the ones that treat surplus hardware with the same rigor they apply to new capital equipment: clear acceptance criteria, credible suppliers with strong quality control, thoughtful integration, and data‑driven maintenance and spares strategies. Approach surplus that way, and it becomes less of a gamble and more of a strategic lever for resilience, cost control, and sustainability.

References

- https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234624622.pdf

- https://pecm.co.uk/finding-value-in-your-surplus-process-plant-equipment/

- https://greenbidz.com/from-liquidation-to-production-how-manufacturers-win-with-surplus-equipment/

- https://www.hollandindustrialgroup.com/blog/the-smart-way-to-sell-surplus-industrial-equipment

- https://manufacturingdigital.com/ai-and-automation/impact-automation-equipment-reliability

- https://pacificic.com/quality-control-in-industrial-parts-supply/

- https://plcautomationgroup.com/blog/obsolete-but-not-out-of-reach

- https://www.realpars.com/blog/factory-acceptance-test

- https://sgbi.us/10-strategies-to-enhance-reliability-of-automation-tests/

- https://unitedindustriesva.com/electric-surplus-manufacturing-efficiency/

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment