-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Cost Comparison Guide for Refurbished DCS Systems

A lot of plants today are trying to squeeze a few more years out of distributed control systems that were installed before some of their current operators were born. Athena Controls has pointed out that tens of billions of dollars’ worth of installed DCS platforms are approaching end of life, with many systems more than 25 years old while the electronics inside them were only ever good for roughly a decade of comfortable service. At the same time, capital is tight, production targets are aggressive, and nobody wants to trigger a large modernization shutdown unless the numbers are absolutely clear.

That is why conversations about refurbished DCS systems and refurbished parts are now happening in every control room and project trailer. Refurbished hardware can look like an elegant way to avoid a multi‑million dollar modernization, but the apparent savings at the parts level can be misleading once you include risk, engineering effort, and long‑term reliability.

In this guide I will walk through how to compare the economics of refurbished DCS systems against alternative strategies, using the lenses that matter to plant leaders: total cost of ownership, safety and reliability obligations, and business risk. The discussion leans on data and concepts from ABB’s refurbished parts programs, modernization cost benchmarks published by Emerson Automation Experts, reliability and maintenance guidance from E2G, and research on remanufacturing control systems and quality costs, translated into something you can actually use in a justification package.

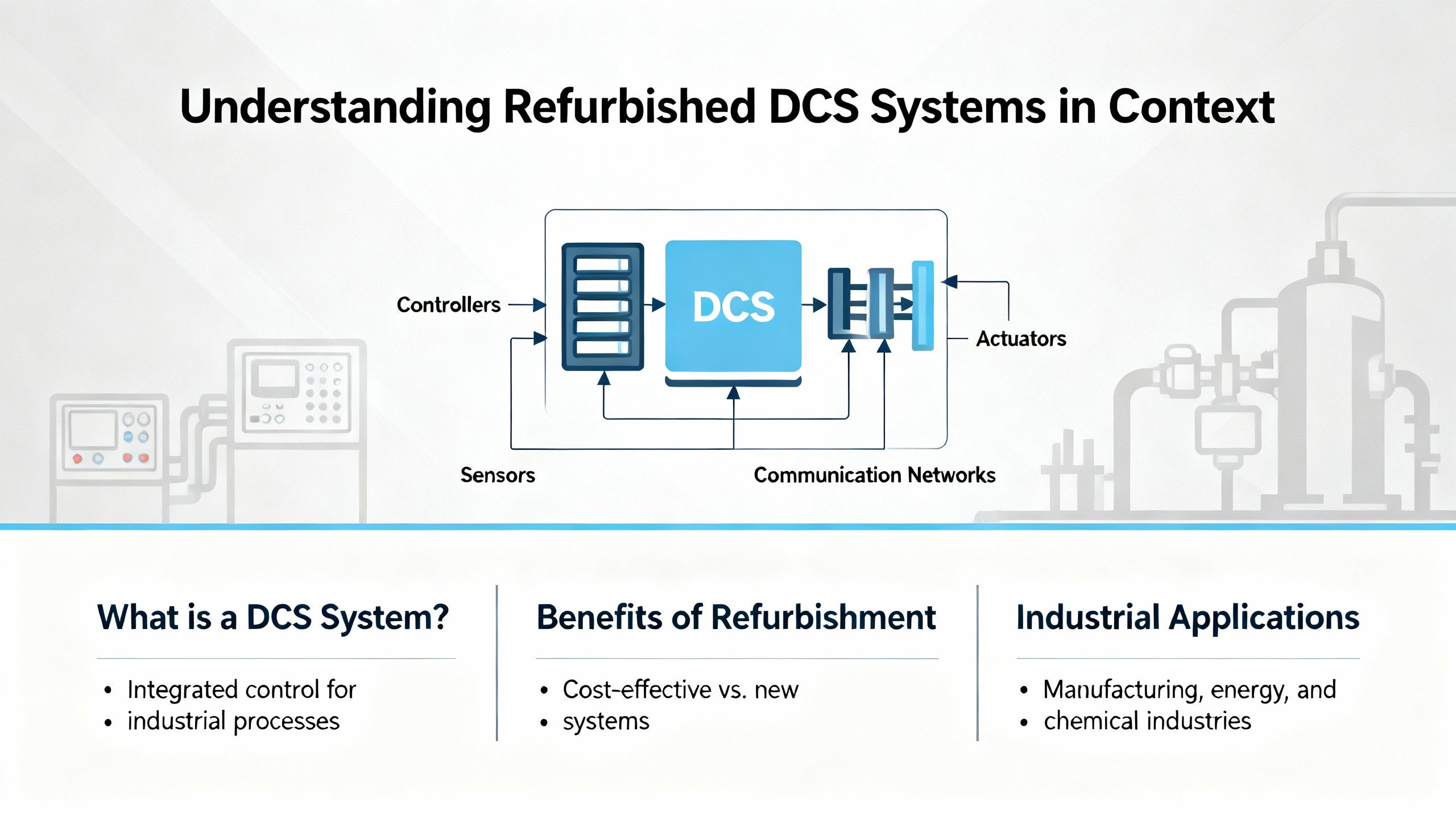

Refurbished DCS Systems in Context

A distributed control system is the nervous system of a process plant. As Automation Community emphasizes, it is the centralized platform for controlling and monitoring industrial processes, and its reliability directly determines plant efficiency, safety performance, and uptime. While programmable logic controllers dominate discrete manufacturing, an article from Industrial Automation Co. notes that DCS architectures are designed for continuous and batch industries such as chemicals, refining, power generation, and water treatment. They use many distributed controllers coordinated through servers and networks, trading raw speed for precise, stable control across large, complex units. The same article stresses that DCS platforms usually involve higher upfront costs than PLC solutions but offer more attractive cost per point and scalability in large, complex operations.

When we speak about a “refurbished DCS system,” we are usually not talking about ripping a system out and installing a completely second‑hand platform. In practice, plants rely on refurbished parts and modules to keep an existing DCS family alive: controller modules, I/O cards, power supplies, communication modules, and sometimes operator stations or network components.

ABB’s own Refurbished Parts Service illustrates what high‑quality refurbishment looks like. ABB describes its refurbished parts as like‑new components that have been recovered, updated, and tested to meet both the original equipment specifications and current component standards. This service is part of ABB’s LifeCycle Parts Services for DCS and is available for several legacy families such as Freelance, Advant Master, Advant MOD 300, Satt, and multiple Symphony systems. Availability depends strongly on each product’s life‑cycle state; for some systems or phases, refurbished parts are only available “on request,” which often means case‑by‑case sourcing and evaluation. For users of those ABB platforms, refurbished parts can be the only realistic way to maintain reliability and regulatory compliance once new hardware is scarce or discontinued.

In the broader electronics world, guidance on refurbished devices distinguishes between manufacturer refurbishment, major retail refurbishing programs, and independent third‑party refurbishers. A consumer‑focused article on checking refurbished device quality explains that manufacturer programs generally apply the strictest quality control, use genuine parts, and back devices with longer warranties. Retail and independent refurbishers can range from excellent to very inconsistent. The same pattern appears in the control world: OEM or OEM‑authorized refurbishment is the closest industrial equivalent to a manufacturer program; ad‑hoc board repair shops sit closer to independent refurbishers. That does not mean third parties are always poor quality, but it does mean you must ask more rigorous questions about test coverage, traceability, and warranty.

It is also important to put refurbishment into the broader lifecycle picture. Automation Community underlines that regular DCS maintenance—physical inspections, preventive tasks, controlled software updates, backups, redundancy, and operator training—can extend system life and prevent many failures. E2G’s work on instrumentation and control systems reliability, tied to OSHA 1910.119 mechanical integrity requirements, makes it clear, however, that there is a point where hardware obsolescence, loss of vendor support, and aging components push risk into unacceptable territory, no matter how diligent your maintenance program is. Refurbished parts live inside that tension between extending life and respecting mechanical integrity obligations.

The Real Cost Structure of DCS Modernization

Before you can judge whether refurbished DCS hardware is economical, you need a realistic sense of what modernizing a DCS actually costs and where that money goes.

Emerson Automation Experts has reported on more than 5,800 modernization projects and points out that most modernization cost does not sit in the DCS hardware itself. According to their 2019 discussion of modernization cost, the heavy hitters are engineering and installation. Newer technologies can significantly shrink those indirect costs, but they never disappear.

For planning and benchmarking, Emerson provides useful rules of thumb. As they describe it, a system replacement that reuses existing cabinets in existing rack rooms tends to come in around $1,500 per I/O point. A full modernization that includes not only system hardware but also field instrumentation and control infrastructure, fully installed, commissioned, and started up, can be closer to $7,500 per I/O point. Site specifics, scope, and risk profile can move those numbers substantially, but they show the scale. In other words, most of what you pay for in a full modernization is everything wrapped around the hardware: design, demolition, wiring, loop checks, testing, cutover, and commissioning.

Emerson also emphasizes that modern technologies such as electronic marshalling with characterization modules, human‑machine interface replacement strategies, and I/O bus interface solutions can redistribute costs between hardware and installation. Even when these newer options cost more per I/O in raw hardware terms, they can shrink the overall project budget by reducing electrical and instrumentation engineering hours, cabinet space, and marshalling complexity.

This is consistent with the Industrial Automation Co. observation that while DCS platforms generally have higher upfront acquisition costs than PLC‑based architectures, they often yield better long‑term economics in large process plants because you are purchasing a scalable, centrally managed automation infrastructure rather than piecemeal hardware.

From a financial perspective, the correct lens is total cost of ownership rather than sticker price. A data center expansion article that focuses on estimating expansion cost makes this point very clearly in a different but related domain. It defines total cost of ownership as the full lifecycle cost of a facility, including construction, IT hardware and software, power, cooling, staffing, and maintenance. It warns against fixating on build cost alone or relying on simplistic industry averages such as per‑square‑foot numbers that may coincidentally match actual project costs rather than explaining them.

The same mindset applies directly to a DCS. Your total cost of ownership for any control strategy—staying on a legacy system, refreshing it with refurbished parts, or modernizing—should include hardware and software, engineering and installation, planned and unplanned downtime, maintenance labor, vendor support, cybersecurity posture, and the flexibility to support new business needs. Even if refurbished parts appear to be cheap on a purchase order, they might be expensive once you factor in risk.

Emerson’s work on modernization justification adds another critical piece: the cost of obsolescence failures. They define obsolescence failure risk as the expected cost of a system shutdown, including the hardware and labor to repair the system, the cleanup and off‑spec product costs, and the value of lost production required to restart the unit, multiplied by the probability of failure. They also note that this probability is hard to quantify without long‑term failure statistics, which many sites do not have. Still, the structure of the calculation is essential when you compare “keep it running with refurbished parts” to “replace it now.”

It is therefore helpful to think about DCS cost elements in a structured way.

| Cost category | What it includes for DCS | Why it matters in refurbishment versus modernization |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware and software | Controllers, I/O cards, network gear, servers, operator stations, licenses, refurbished modules | Refurbishment mainly moves this category; modernization changes it and may reduce per‑point cost over time through better architectures |

| Engineering and installation | Design, programming, documentation, cabinet work, field wiring, loop checks, testing, commissioning | Emerson notes that this category dominates modernization budgets; refurbishment typically minimizes these costs in the short term |

| Planned and unplanned downtime | Outage windows for projects, trips and failures during operation, time to diagnose and repair | Refurbishment avoids major planned outages but may increase unplanned ones if reliability is weaker; modernization reverses that |

| Maintenance and lifecycle support | Preventive maintenance, spare parts, training, vendor contracts, end‑of‑life transitions | Legacy systems with refurbished parts can become increasingly hard to support, especially as OEM knowledge and spares disappear |

| Risk, safety, and compliance | Mechanical integrity obligations, safety instrumented systems performance, cybersecurity, audits | Refurbished hardware living in obsolete platforms may leave or push you out of compliance; modern platforms can make compliance easier |

| Future capability and integration | Advanced process control, data historian and analytics, integration with MES and ERP, remote access | Modern DCS platforms enable capabilities that legacy systems, even with refurbished parts, struggle to support or secure |

In a cost comparison, refurbished DCS parts mostly affect the first row and partially the second and fourth. Modernization reshapes every row. If you only look at hardware cost, refurbished modules will almost always win. If you widen the lens to the whole table, the answer becomes more nuanced.

What Refurbished DCS Parts Really Save, and What They Do Not

ABB’s refurbished parts program demonstrates the strong side of refurbishment. For users of legacy ABB families, those parts are formally tested to meet original and current standards and give a realistic path to extend the life of functioning systems. When new hardware is unavailable or prohibitively expensive, they are sometimes the only way to uphold reliability and compliance. In that scenario, refurbished parts clearly save immediate capital and can prevent premature modernization projects.

Swapping in a refurbished controller or I/O card has another obvious benefit: you avoid the engineering and installation burden described by Emerson. A like‑for‑like module exchange requires minimal design changes and can often be done in a short maintenance window, with limited testing scope confined to the affected loops.

However, refurbishment generally does not reset the age of the overall architecture. Athena Controls describes multiple structural challenges that accumulate in legacy platforms. Hardware obsolescence is one. OEMs stop manufacturing or certifying old boards, spare parts become scarce or only available as used or remanufactured units, and both redundant and non‑redundant systems experience increasing failure rates. They also highlight loss of tribal knowledge as seasoned engineers retire, poor or missing documentation, limited scalability, fragmented software and firmware, limited connectivity to modern IT systems, and increased cyber risk due to outdated operating systems and communication stacks.

Refurbished parts can address the immediate symptom of a failed module but they do not make your operating system current, they do not fix a brittle, undocumented application, and they do not teach your next generation of engineers how to work safely and efficiently with a platform that has been out of mainstream training for years.

From a safety and compliance perspective, E2G’s guidance on instrumentation and control systems reinforces the limits of refurbishment. OSHA 1910.119’s mechanical integrity element explicitly covers controls and protective devices such as sensors, alarms, interlocks, and emergency shutdown systems. Safety instrumented systems, governed by ANSI/ISA 61511 as recognized and generally accepted good engineering practice, require documented operations, maintenance, testing intervals, and replacement strategies for every safety instrumented function. E2G also distinguishes between evident failures, which are self‑revealing, and hidden failures, which can remain dormant until another failure combines with them. Hidden failures are often associated with protective functions.

If refurbished DCS components sit inside or adjacent to these protective layers, your cost comparison must account for the risk that a lower‑confidence component increases the chance of a hidden failure. That is not an argument against refurbishment per se, but it is a reminder that the economics of a spare board in an operator display are very different from the economics of a module in a shutdown logic path.

Applying Remanufacturing Economics to DCS Decisions

A useful way to bring discipline into refurbishment discussions is to borrow methods from formal remanufacturing research. A technical study on remanufacturing electrical control systems for drilling rigs, published in an engineering journal, develops a decision‑support system for choosing remanufacturing schemes. The system combines fuzzy comprehensive evaluation with an artificial neural network cost model to cope with uncertainty.

In that study, the authors decompose an electrical control system into categories of parts such as wearing parts that are low value and easily damaged, easy‑to‑wear parts that have high remanufacturing profit and can survive multiple overhaul cycles, and non‑wearing parts that rarely fail and can also be remanufactured multiple times. For a key component like a main motor spindle, they build a neural network that predicts remanufacturing cost from nondestructive test indicators of precision loss, stiffness, and strength. Training data for 20 samples shows discrete cost levels at roughly 1,870, 4,290, 7,890, and 9,200 CNY corresponding to different degradation states, with validation tests showing small prediction errors between actual and predicted costs.

The authors then apply a very practical rule: if the predicted remanufacturing cost is less than about seventy percent of the cost of a new component, the part is considered to have remanufacturing value. If predicted remanufacturing cost rises above that threshold, the part is routed to material recovery rather than remanufactured for reuse.

While this study focuses on drilling‑rig equipment rather than process DCS hardware, the economic logic is directly applicable. You can treat each major DCS component type—controllers, I/O racks, power supplies, network devices—as a candidate for refurbishment and ask, in effect, how much it would cost to bring this module to a tested, acceptable state compared with buying new or modernizing. You might not build a full neural network, but you can estimate refurbishment cost and risk based on bench test results, supplier history, and failure data.

The seventy‑percent threshold is not a universal law. It is, however, a rigorous starting point. If a refurbished or remanufactured DCS component, including the cost of sourcing, testing, and installing it, is approaching or exceeding seventy percent of a new, supported equivalent, it becomes hard to justify on economic grounds once risk is included. At that point, the argument shifts toward modernization, even if modernization requires a staged plan.

This line of thinking meshes well with the classic quality cost framework described in a Benchmark Six Sigma discussion of quality costs. They classify quality costs into prevention costs, appraisal costs, and the cost of poor quality. Prevention costs are investments you make to avoid defects in the first place, such as better processes, training, and engineering. Appraisal costs are the costs of inspection and testing to catch defects before customers see them. The cost of poor quality encompasses internal failure costs, such as rework or scrap discovered before shipment, and external failure costs, such as warranty work, customer dissatisfaction, and lost business.

In DCS terms, prevention costs include good design, robust maintenance, and careful vendor selection for refurbished hardware. Appraisal costs include rigorous staging, factory acceptance tests, and site acceptance tests when you introduce refurbished components. The cost of poor quality may show up as unplanned plant trips, reprocessing off‑spec product, safety incidents, or damaged customer relationships if supply is disrupted. A cheap refurbished module that fails at the wrong time may create a huge external failure cost.

It is often useful to make this explicit by mapping quality cost categories to your DCS refurbishment choices.

| Quality cost category | DCS refurbishment example |

|---|---|

| Prevention cost | Time spent qualifying refurbishment suppliers, specifying test requirements, maintaining documentation and spare strategies, and planning phased modernization |

| Appraisal cost | Bench testing of refurbished modules, offline simulation of critical loops, extended burn‑in before deploying modules to high‑risk services |

| Internal failure cost | Unit trip during startup because a refurbished module behaves inconsistently, resulting in rework and delays before product reaches customers |

| External failure cost | Contract penalties or lost orders after a major unplanned outage caused by a latent fault in refurbished hardware, compounded by reputational damage |

When you combine remanufacturing thresholds with quality cost thinking, the purely price‑based appeal of refurbished DCS hardware often softens. The more critical the service and the higher the consequence of failure, the lower the percentage of new cost you should be willing to pay for refurbishment.

Judging the Quality and Price of Refurbished DCS Hardware

Even when refurbishment makes economic sense in principle, the actual value depends heavily on who is doing the work and how they price it.

The article on checking refurbished device quality in consumer markets recommends vetting refurbishers by their reputation, years in business, certifications, and track record of resolving customer complaints. It notes that manufacturer‑refurbished devices usually use original parts, undergo strict testing, and carry longer warranties, while retailer and independent programs can be more variable and may use mixed or non‑original parts.

For DCS hardware, OEM or OEM‑authorized refurbishment, such as ABB’s Refurbished Parts Service, comes closest to the manufacturer category. These programs describe formal testing against original and current standards and often integrate with documented life‑cycle management processes. Independent refurbishers and board repair shops can have excellent technicians but frequently lack the formal validation, traceability, and long‑term support commitments of an OEM. In practice, this means you should seek detailed information about their test procedures, whether they test under realistic process loads, and what documentation accompanies the parts.

The same consumer guidance stresses the importance of warranties and return policies. Warranties in the six‑ to twelve‑month range are common for refurbished electronics, with shorter windows often viewed as a warning sign. In industrial automation, the exact numbers will differ, but the principle holds. You want warranty coverage that is meaningful relative to your operating patterns and risk exposure, with clear rules on what happens if a refurbished part fails in service. Return policies that allow you to reject parts that do not meet advertised condition after reasonable bench tests are equally important.

A farm equipment article on evaluating and pricing used equipment introduces another useful concept: retail cash to book value. That metric is defined as the selling price divided by the dealer’s book value after reconditioning. Dealers aim for a healthy percentage, often around eighty‑five percent or higher, to ensure profitability without overstating asset value. The broader lesson for DCS purchasers is to know both your own cost basis and the market. If a refurbished module is priced close to a new one, the seller might be capturing too much of the economic benefit, especially if you bear most of the operational risk. If a part is very cheap, you should ask why and invest more heavily in appraisal and preventive costs.

On the technical side, the same refurbished‑device guidance strongly recommends thorough inspection and functional testing as soon as a refurbished device arrives. Translating that to DCS components, you should plan to test refurbished hardware in a controlled environment before exposing live production to it. That can mean installing modules in a test rack, running simulated I/O traffic, verifying communication performance and diagnostics, and deliberately cycling power and network links to stress behavior.

Advanced checks may include running manufacturer diagnostics, monitoring temperatures under load, and reviewing error logs after sustained operation. In a high‑risk environment, it can be worth paying for an independent or OEM service group to certify key refurbished components before assigning them to safety‑related or high‑consequence duties.

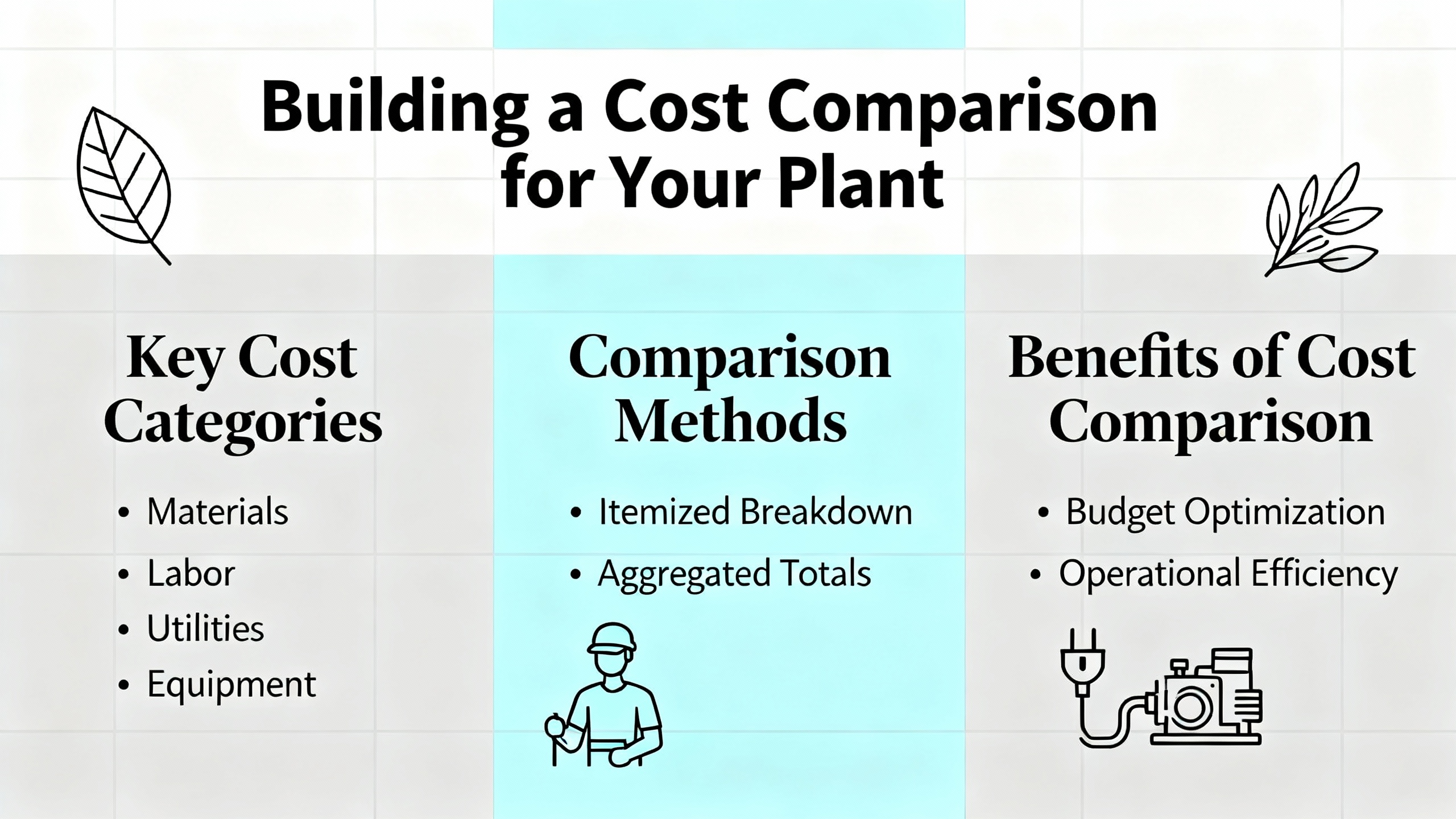

Building a Cost Comparison for Your Plant

Turning all of this into a structured cost comparison requires a few disciplined steps.

First, define your base case clearly. Emerson’s modernization justification guidance treats the base case not as a scenario where you spend nothing, but as the net present value of continuing to run the existing DCS until it is ultimately replaced, with obsolescence failure risk explicitly included. That means you need at least rough estimates for the probability and consequence of significant system failures over your planning horizon, in the way Emerson defines obsolescence risk: repair hardware and labor, cleanup, off‑spec product, and lost production multiplied by failure probability.

Second, define at least two realistic alternatives. One is a refurbishment‑heavy strategy that keeps the legacy DCS in place, relies on refurbished modules and parts to manage failures, and perhaps applies selected lifecycle upgrades such as operating system updates where the platform allows it. The other is one or more modernization options that range from hybrid approaches, which reuse cabinets and wiring, to full modernizations that replace controllers, I/O, and instrumentation where appropriate. The cost‑per‑I/O benchmarks Emerson shares help you scale each modernization option, while the ABB refurbished parts example anchors what a credible refurbishment program can look like.

Third, use risk‑based reliability methods to prioritize where refurbishment belongs. E2G’s reliability‑centered maintenance and instrument risk ranking guidance suggests building a cross‑functional team to classify instruments and loops by consequence of failure, across safety, environmental, and commercial dimensions. Instruments and logic associated with safety instrumented systems and other protective layers will fall into the highest criticality brackets and warrant the most conservative hardware strategies. In many plants, this leads to a blended approach: refurbished parts may be accepted in low‑consequence services while high‑consequence paths move sooner to modern platforms.

Fourth, apply total cost of ownership thinking to each scenario. The data center expansion article warns against using simplistic industry averages like cost per square foot as the main design driver. The direct equivalent in DCS projects is to avoid using only cost per point or module price as your deciding metric. For each scenario, build a lifecycle cost model that includes capital expenditure for hardware and engineering, planned shutdown costs, expected unplanned outage costs, maintenance and support costs, and the economic value of new capabilities such as advanced control, better analytics, or improved connectivity to planning and execution systems. Emerson highlights that modern DCS platforms can provide better information on when to act, support advanced control strategies, and integrate more easily with enterprise systems, all of which can translate into ongoing performance benefits that should be reflected in your cash‑flow assumptions.

It can be helpful to summarize the comparison in a simple matrix.

| Strategy | Description | Where cost and risk concentrate | Typical sweet spots |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legacy DCS with refurbished parts | Keep existing platform, rely on refurbished modules and incremental maintenance to extend life | Lower immediate hardware expenditure, but increasing obsolescence risk, hidden failure risk, and reliance on shrinking pools of expertise and documentation | Short planning horizons, limited capital, low‑criticality units, or as a bridge while a disciplined modernization plan is developed |

| Hybrid modernization | Replace controllers, servers, and networks while reusing existing cabinets and sometimes I/O, often aided by migration tools | Moderate hardware spend, significant but contained engineering and installation costs, risk managed through staged cutovers and extensive testing | Plants that need modern capabilities and risk reduction but must minimize outage duration and reuse existing infrastructure where feasible |

| Full modernization | Replace DCS, often along with field instrumentation and control infrastructure, to a modern platform | Highest upfront cost per I/O as Emerson’s $7,500 rule of thumb illustrates, but strongest long‑term risk reduction and capability gains | High‑criticality facilities with severe obsolescence, safety, or cyber risks, or sites that need a platform aligned with ambitious future integration and analytics goals |

In many brownfield plants, the answer is not a single strategy but a phased roadmap. Athena Controls argues for disciplined modernization rather than simply stockpiling spares. That mindset aligns well with combining a limited, high‑quality refurbishment program to keep today’s risk acceptable while designing and justifying a staged modernization that aligns with business priorities and outage opportunities.

When Refurbished DCS Systems Make Strategic Sense

Refurbished DCS hardware is at its best when it is used deliberately rather than reflexively. There are several situations where it can be the right move.

Refurbishment is particularly useful as a bridging strategy when a legacy platform still meets process needs and regulatory expectations, but the business is not ready for a modernization project. In that case, OEM‑refurbished parts, backed by documented testing and appropriate warranties, can keep the platform stable while you collect data, build a business case following Emerson’s net present value approach, and design a modernization roadmap that reflects E2G’s risk rankings and OSHA mechanical integrity requirements.

Refurbished parts also make sense in lower‑criticality services where the cost of poor quality, in Benchmark Six Sigma’s terms, is genuinely small. For a non‑critical utility system, a refurbished controller that saves significant hardware cost might be entirely appropriate if you have strong appraisal practices—good testing and monitoring—and a clear response plan for failures.

By contrast, refurbished hardware is a weaker fit where the system’s structural limitations already violate or strain modern expectations. Athena Controls describes legacy systems that struggle with integration to web, mobile, cloud, MES, and ERP systems and whose old operating systems and early‑generation communications can create cyber‑security exposure. In those cases, continued reliance on refurbished parts can trap you in an architecture that undermines both security and flexibility. No matter how good the refurbished hardware is, the total cost of ownership and risk may still favor modernization.

The remanufacturing research on drilling‑rig control systems and the seventy‑percent threshold offers a practical way to formalize these intuitions. If a refurbished or remanufactured DCS component can be acquired, tested, and installed for a small fraction of the cost of modernizing the equivalent function, and if it sits in a low‑consequence service, refurbishment can be economically sound. As costs or risk increase, the balance shifts toward modernization.

Short FAQ

Are refurbished DCS parts as reliable as new ones?

OEM‑refurbished DCS parts, such as those described in ABB’s LifeCycle Parts Services, are tested to meet original equipment specifications and current component standards, and in that sense are intended to perform like new parts. Reliability in practice depends not only on the part itself but also on the age and condition of the surrounding system, the quality of installation, and the rigor of your maintenance and testing program. Refurbished parts from independent sources may not have undergone the same level of validation, so you should treat them with greater scrutiny, using the quality cost framework to justify additional preventive and appraisal effort.

How should I explain the economics of refurbishment to non‑technical management?

The most effective explanations combine a simple percentage rule with a total cost of ownership view. You can point to remanufacturing research on control systems that treats parts as candidates for refurbishment only while their remanufacturing cost stays well below the cost of new, often using a seventy‑percent threshold as a decision point. Then frame your options using Emerson’s approach: compare the net present value of continuing with refurbishment against the net present value of modernizing, explicitly including the expected cost of failures and the value of modern capabilities such as better control, analytics, and integration. This shifts the conversation from arguing about the price of a single module to choosing the most economical risk and performance profile for the plant.

Closing

Refurbished DCS systems and parts are not a shortcut around doing the hard thinking on lifecycle, risk, and modernization; they are one tool in that broader strategy. When you ground your decisions in solid reliability principles, realistic cost benchmarks, and disciplined evaluation of refurbishers, you can use refurbished hardware to buy time and reduce waste without betting the plant on wishful thinking. That is the way seasoned integrators and project partners look at it: treat every spare, whether new or refurbished, as part of a long‑term plan rather than a one‑off bargain.

References

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9132273/

- https://www.athenacontrols.com/todays-challenges-of-maintaining-legacy-control-systems/

- https://automationcommunity.com/dcs-maintenance/

- https://zextons.co.uk/blogs/how-to-check-the-quality-of-refurbished-devices-before-buying

- https://www.controleng.com/considerations-for-dcs-modernization-for-process-control-systems/

- https://www.csemag.com/know-whether-its-time-to-replace-a-control-system/

- https://www.dcsmi.com/data-center-sales-and-marketing-blog/how-to-estimate-data-center-expansion-costs

- https://control.com/technical-articles/how-to-successfully-choose-control-system-replacements/

- https://e2g.com/industry-insights-ar/instrumentation-and-control-systems-reliability-and-maintenance-best-practices/

- https://industrialautomationco.com/blogs/news/plc-vs-dcs-which-control-system-suits-your-manufacturing-needs?srsltid=AfmBOoqCgJwfuIVQXzENlZev_WndbUFq7ip-JGMaTQShWGJydVMKp5Jm

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment