-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

How to Select the Right Communication Module for Industrial Network Integration

When a project stalls on “network issues,” it almost never turns out to be a cable fault. In my experience, the real choke point is usually the communication interface between a device and the plant network. That interface is the communication module, and selecting it well is the difference between a smooth FAT and weeks of painful troubleshooting on site.

Industrial networking guides from organizations such as Motion Industrial, Mitsubishi Electric, Renesas, Texas Instruments, and HMS Networks all converge on one message: your network is strategic infrastructure. Communication modules are how your equipment plugs into that infrastructure. Choosing them on catalog price alone is asking for trouble.

This article walks through how to select communication modules pragmatically, based on real plant and OEM constraints, using lessons learned from multi-protocol projects and the research sources provided.

Start with the Network, Not the Module

Before you think about module form factors or chipsets, you need a clear picture of the network landscape you are integrating into.

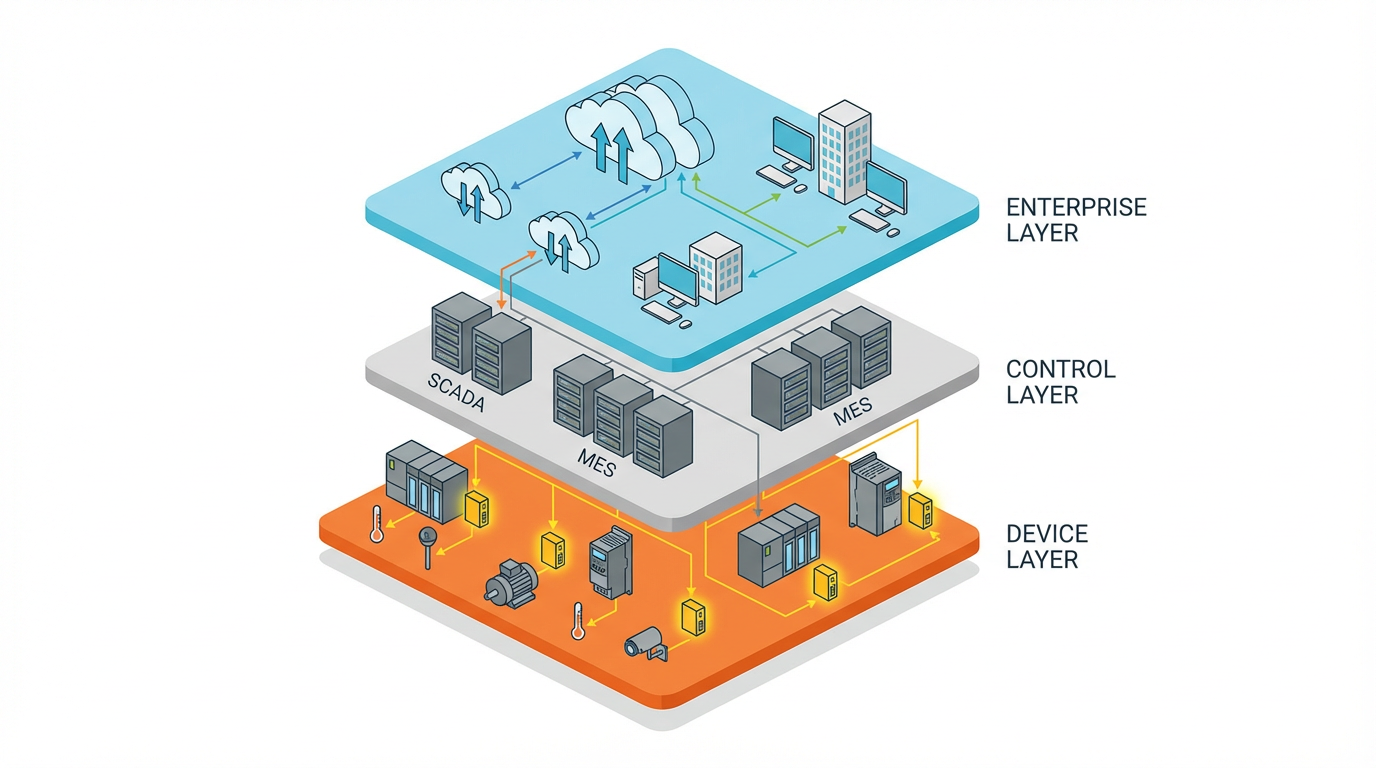

Industrial networking references from Motion Industrial and Control Engineering describe several overlapping layers:

At the top, enterprise and business operations networks connect offices, data centers, and cloud platforms. Their job is data accessibility, analytics, and corporate systems.

In the middle, supervisory and information networks support SCADA, historians, MES, and thin clients. These networks span multiple production areas and carry monitoring and control data, but they are less time-critical than motion loops.

At the bottom, process control and device-level networks connect PLCs, drives, robots, sensors, and safety systems. They must be robust, deterministic, and resilient to electromagnetic interference, because they directly affect product quality and safety.

That bottom layer is where your communication module lives.

It has to speak the language of the plant’s control network while still fitting the mechanical, environmental, and cost constraints of the device you are integrating.

HMS Networks’ market studies make it clear that there is no single “winner” here. Industrial Ethernet has grown strongly, but more than twenty protocols still have meaningful share, with strong regional biases and large installed bases of legacy fieldbus and serial systems. That fragmentation is exactly why getting the module decision right matters.

Clarify the Integration Problem You Are Actually Solving

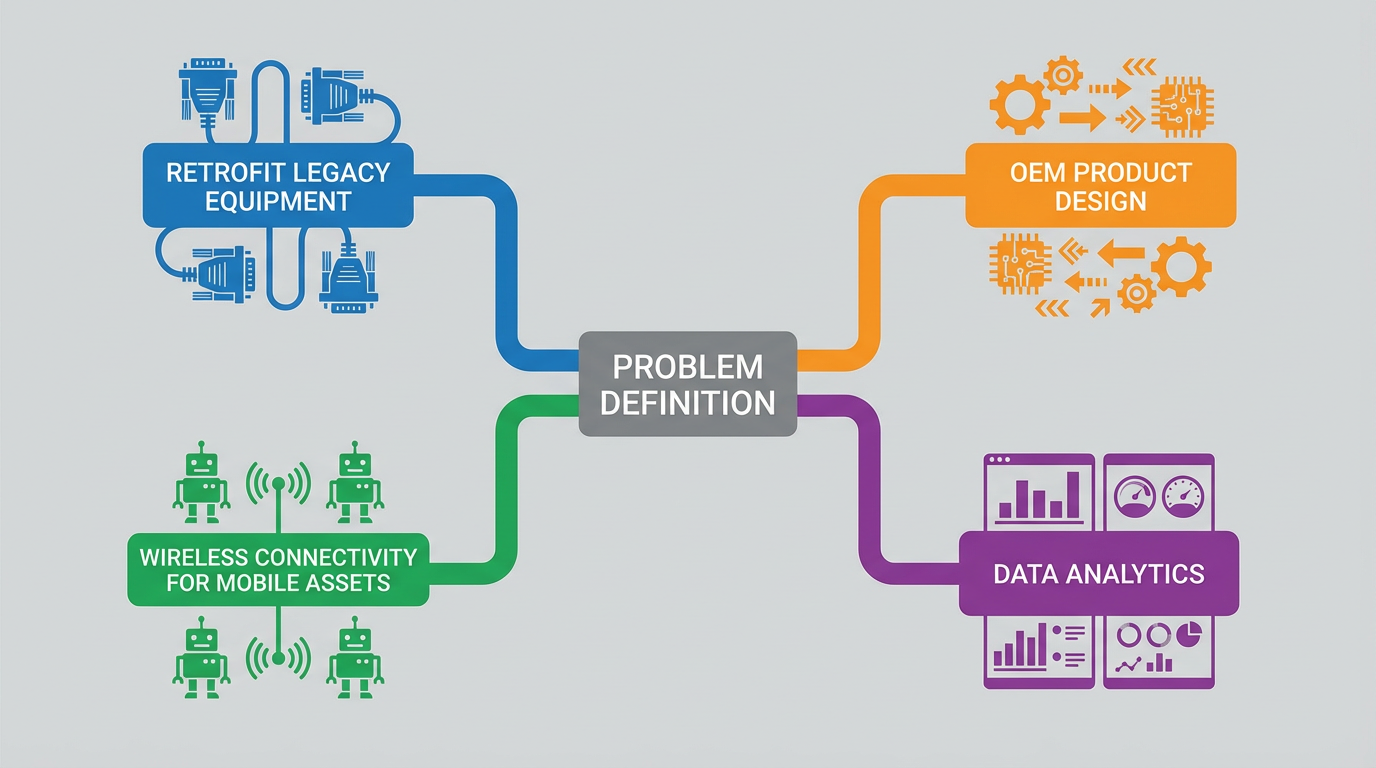

“Select a communication module” sounds like a single task, but it hides several very different problems. The right choice for an OEM selling thousands of drives is not the same as the right choice for a system integrator adding a few new skid-mounted units into an older plant.

Common scenarios include the following.

You might be retrofitting legacy equipment. Electrical Technology’s overview of industrial networks highlights extensive installed bases of serial and fieldbus technologies such as RS‑232, RS‑485, Profibus, DeviceNet, and Foundation Fieldbus. These devices often run reliably but sit isolated, so you need a module or gateway to bridge them into a modern Profinet, EtherNet/IP, or Modbus TCP backbone.

You might be designing a new OEM product. HMS Networks points out that multi-network connectivity is a core go-to-market challenge. Different customers and regions expect different protocols, and your product has to adapt without a redesign each time.

You might be extending connectivity to moving or rotating parts or to hard-to-wire assets. CoreTigo and other industrial wireless specialists describe how robotics, transport tracks, and mobile assets strain traditional cabling. In that case, your “communication module” may be an IO-Link Wireless or other industrial wireless interface, not just another Ethernet port.

You might be enabling data-driven maintenance and analytics. Motion Industrial and Advantech both stress that modern networks support real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance, and cross-system analytics. In these projects, your module must not only carry control traffic but also expose richer diagnostics, device metadata, and historical data upstream.

Only once you are clear about which of these problems you are solving does it make sense to choose a communication module architecture.

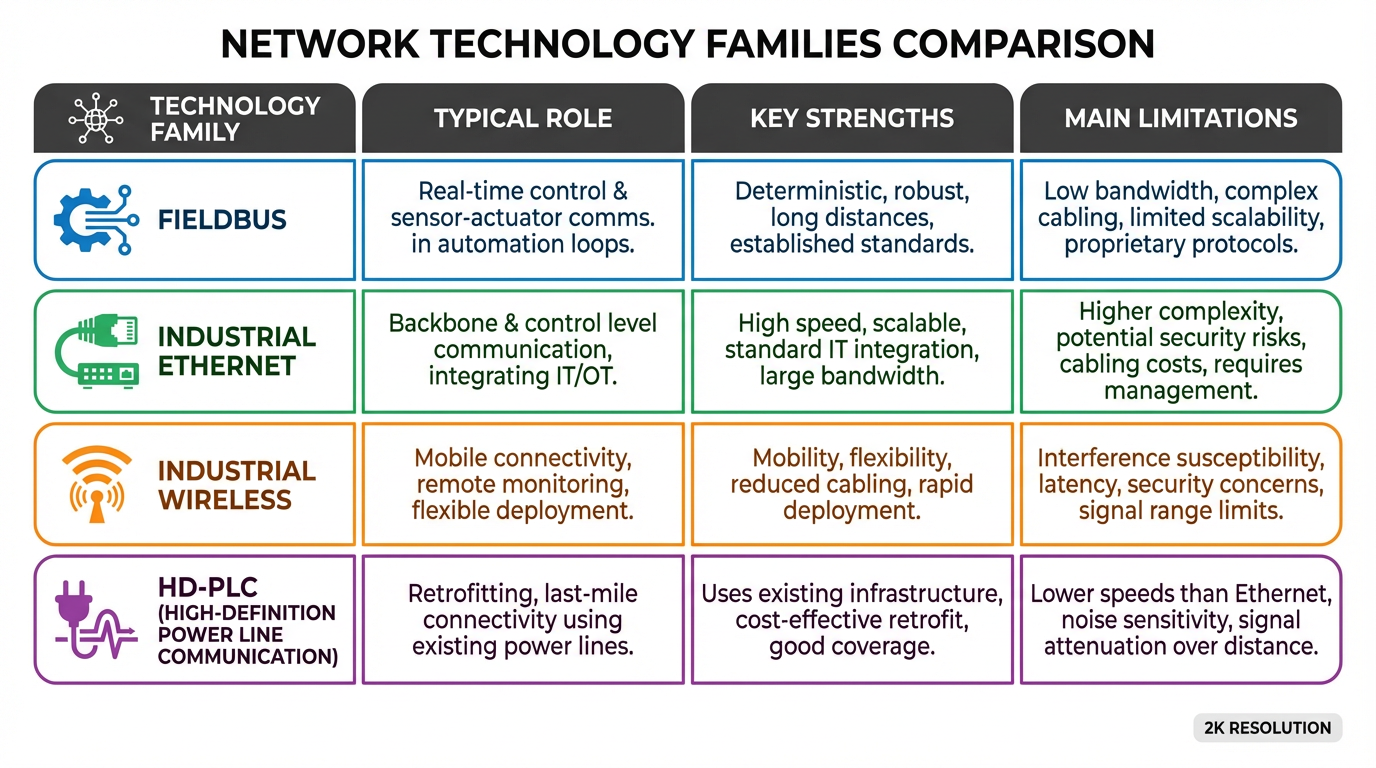

Know Your Networks: Fieldbus, Industrial Ethernet, Wireless, and HD‑PLC

Communication modules do not exist in a vacuum. They are tightly coupled to the underlying network technology. The research notes highlight four broad families you need to understand.

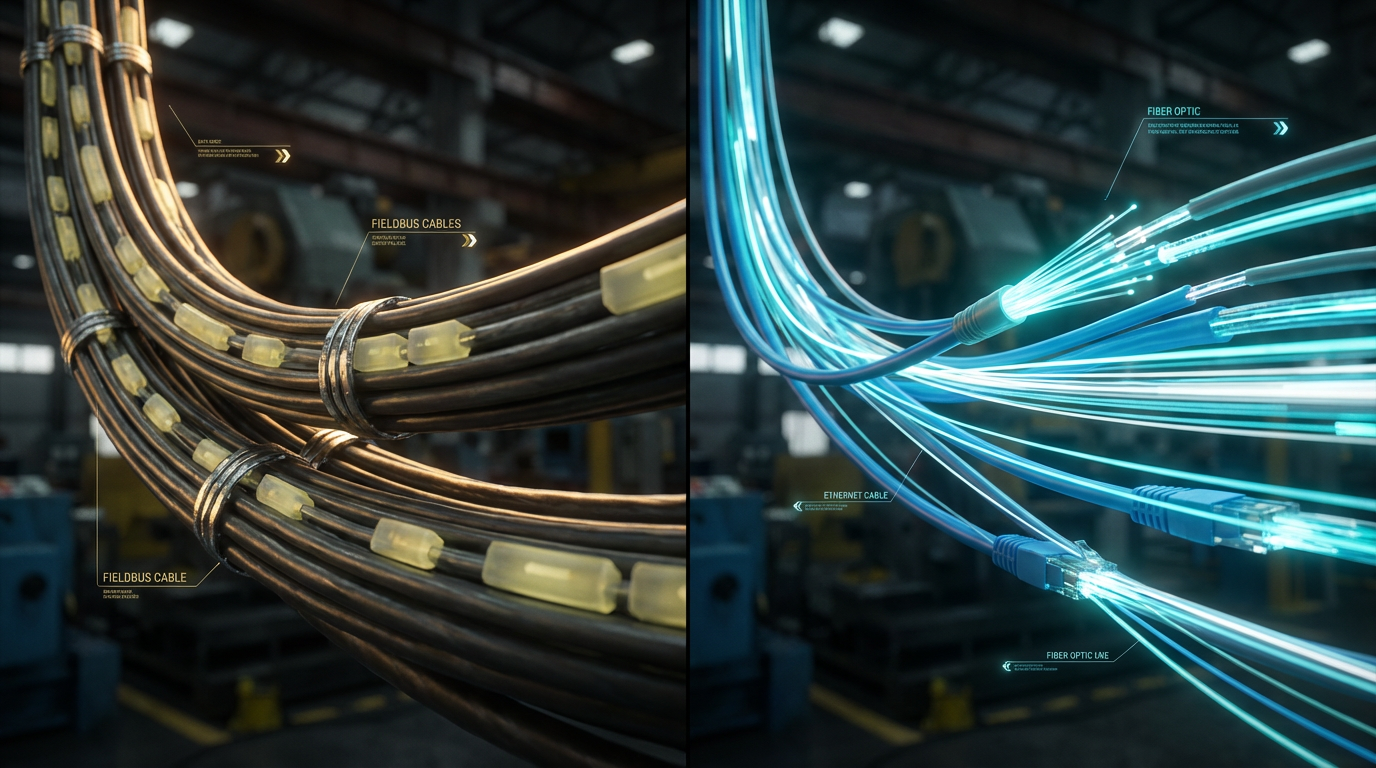

Fieldbus: Durable but Bandwidth-Limited

Fieldbus systems such as Profibus and Foundation Fieldbus, summarized by Electrical Technology and Nessum’s analysis, were designed to replace bundles of point-to-point analog and serial cables with a multi-drop digital bus. They are durable, interoperable across vendors, and have served process and factory automation well for decades.

Their drawbacks are just as important. Nessum’s market survey notes that fieldbus equipment tends to be expensive, data rates are modest, and each ecosystem often requires specialist knowledge. If your device primarily targets legacy plants with strong Profibus or other fieldbus installed bases, you may need a fieldbus-capable module or gateway. For new designs, fieldbus alone is rarely enough.

Industrial Ethernet: High Performance with Higher Complexity

Industrial Ethernet protocols such as Profinet, EtherNet/IP, EtherCAT, CC‑Link IE, Modbus TCP, and POWERLINK dominate new installations, according to market figures and guidance from Renesas, Nessum, and Control Engineering.

Texas Instruments’ technical material emphasizes why these technologies require more than a standard Ethernet interface. Many implementations use cut-through forwarding and deterministic scheduling to achieve cycle times around one millisecond for standard I/O, and down to tens of microseconds for advanced Profinet IRT motion control. EtherCAT devices, for example, can achieve port-to-port delays around one microsecond as the frame passes through each node.

The payoff is high bandwidth, determinism, and the ability to converge multiple functions—control, safety, and even IIoT traffic—onto one network. The cost is higher infrastructure complexity, the need for specialized MACs or protocol stacks, and certification requirements.

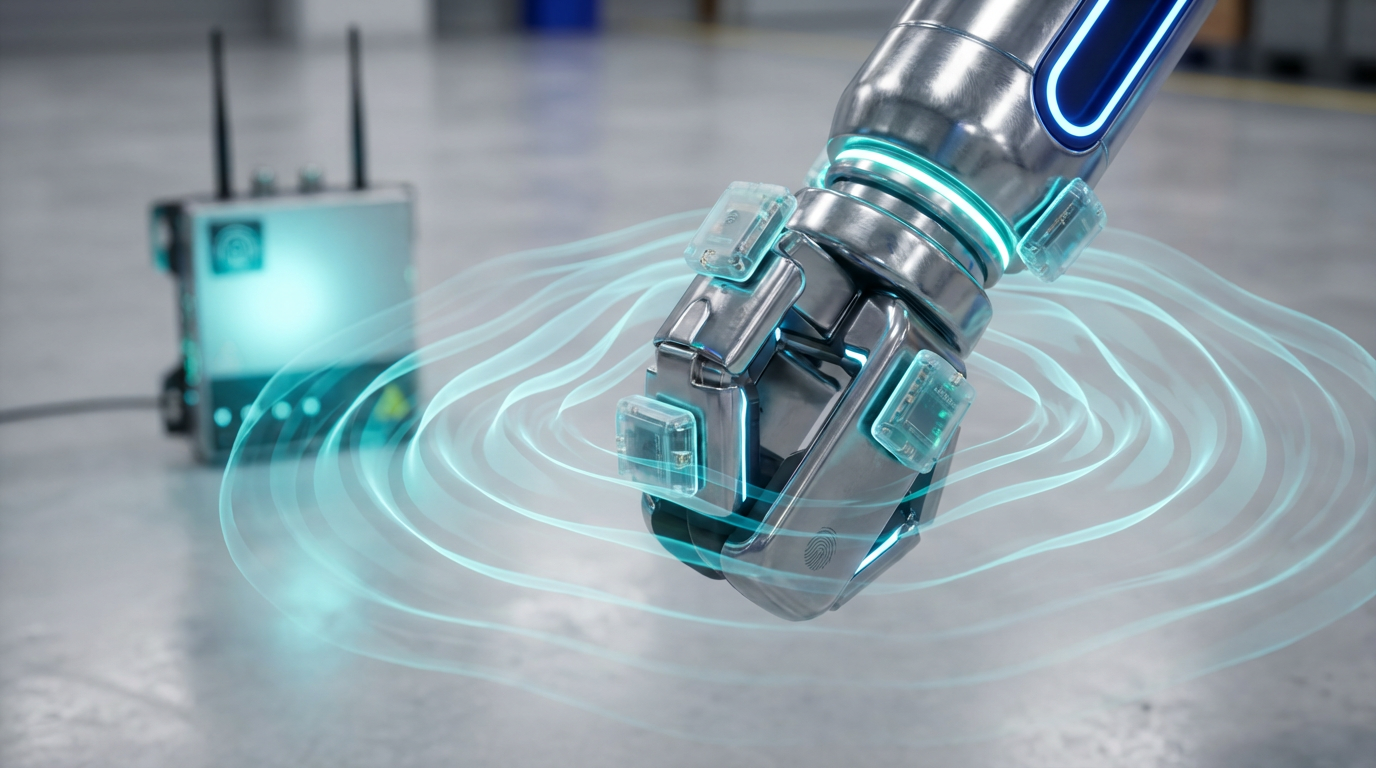

Industrial Wireless and IO‑Link Wireless

Industrial wireless, as described in the CoreTigo and Nessum material, offers flexibility and mobility that copper or fiber cannot. It enables remote monitoring, mobile robots, and rapid reconfiguration without re-pulling cable.

However, generic Wi‑Fi and Bluetooth often perform poorly in dense industrial environments, suffering interference and collisions. CoreTigo’s guidance explicitly warns that nonindustrial protocols tend to struggle in factories and recommends purpose-built industrial wireless, such as IO-Link Wireless, for critical automation use.

IO-Link Wireless, described in CoreTigo’s introduction to industrial communication networks, provides deterministic, bidirectional communication between sensors, actuators, and PLCs through a wireless master. Key figures include roughly five millisecond latency for up to forty nodes within about sixty-five feet and an extremely low packet error rate around one in a billion, achieved through careful use of the 2.4 GHz band. For moving tools and short-range machine-level networking, this can be an excellent complement to wired Industrial Ethernet.

HD‑PLC over Existing Cabling

Nessum’s overview of industrial networking solutions introduces HD‑PLC, a power line communication technology that runs data over existing wiring, including power lines, twisted pair, and coax. It offers theoretical physical layer speeds up to about 240 Mbps and practical throughput in the tens of Mbps range, above typical fieldbus rates but usually below full Industrial Ethernet.

The strengths are reduced cabling, cost-effective large-scale networks with multi-hop topologies, and good reliability by reusing proven plant wiring. Nessum positions HD‑PLC as a “best of both worlds” option where you need more performance than classical fieldbus but cannot justify the cost and complexity of a full Industrial Ethernet build-out.

Comparing the Network Families

A communication module selection usually boils down to which of these underlying technologies you need to support, and at what level of performance, cost, and flexibility. The following summary reflects the research sources.

| Technology | Typical role | Key strengths | Main limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fieldbus | Legacy device and process networks | Durable, proven, multi-vendor interoperability | Low bandwidth, higher cost, specialist skills |

| Industrial Ethernet | New control and information networks | High speed, determinism, rich features | Higher infrastructure and lifecycle cost |

| Industrial wireless / IO-Link Wireless | Mobile or hard-to-wire assets | Flexibility, scalability, reconfigurability, short-range determinism with IO-Link Wireless | Susceptible to interference if not engineered; coverage planning required |

| HD‑PLC | Reusing existing cabling at mid speeds | Minimal new wiring, cost-effective large networks | Below top-end Ethernet speeds, protocol ecosystem still maturing |

Your communication module strategy has to align with this mix, not ignore it.

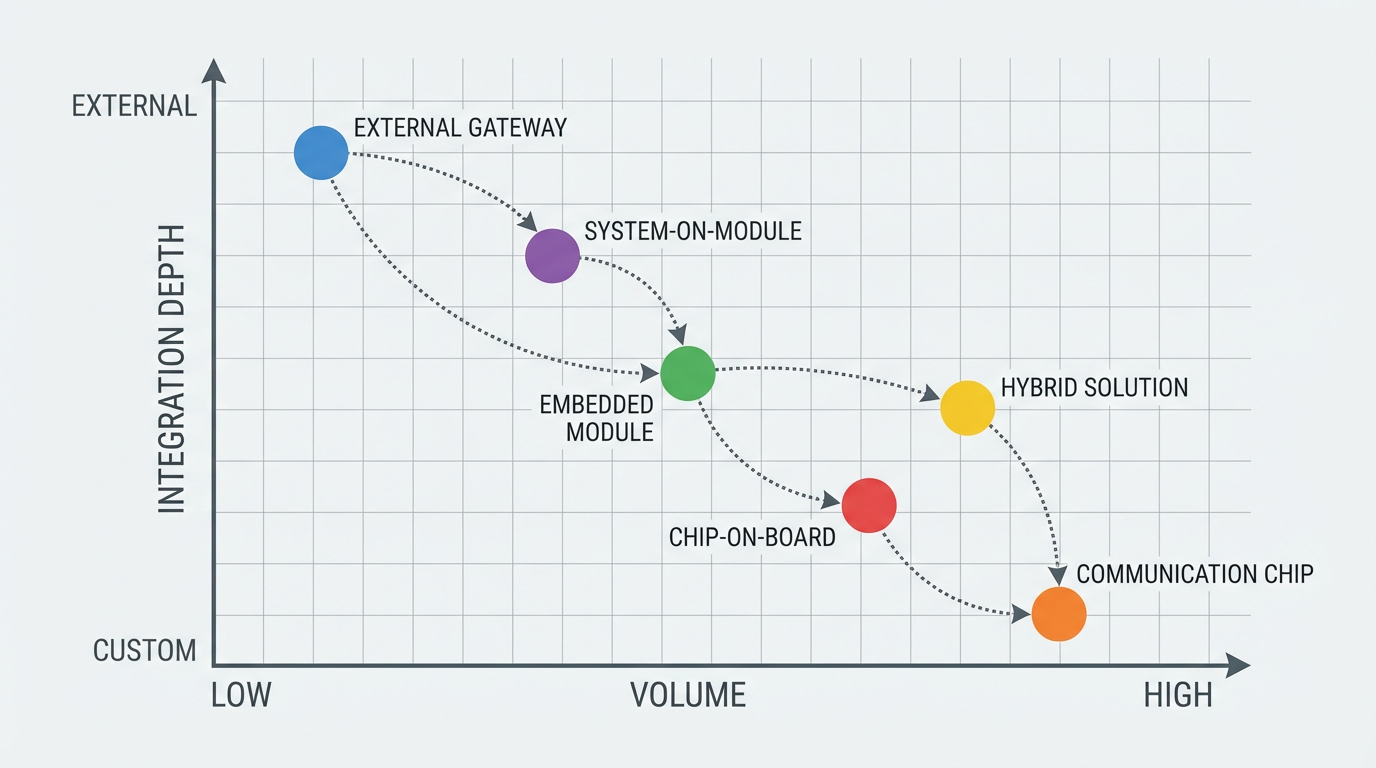

Communication Module Architectures: Pros and Cons

HMS Networks’ guide to connecting automation machines, together with Texas Instruments’ and Renesas’ device portfolio information, outlines the main architectural options for adding network connectivity to a product or system.

External Gateways and Protocol Converters

External gateways are stand-alone boxes that translate between, for example, Modbus RTU and Profinet, or EtherNet/IP and CAN-based networks. According to HMS, they require no changes to your device hardware, are configured through web tools rather than programming, and are the fastest option for low-volume or retrofit projects.

They are ideal when you only need a handful of units, or when you are integrating third-party equipment you cannot modify. The downside is cost per node and the fact that the network interface is not embedded in the device; there is one more box to mount, power, and maintain.

Embedded Communication Modules

Embedded communication modules are pluggable boards that drop into a slot on your device and provide the full stack: hardware, network connectors, protocol stacks, and often security features. HMS notes that these modules are popular because they drastically shorten time-to-market, offer pre-certification for major networks, and can be swapped to support more than twenty protocols.

Their weaknesses are mechanical constraints and unit price. The fixed module form factor and connector layout may not suit very compact or cost-sensitive designs. For high-volume products, module cost can dominate the bill of materials, pushing you to a deeper integration.

Communication Bricks and Solder-On Interfaces

HMS describes pluggable communication bricks as fully embedded modules mounted on your main circuit board. They contain the communication hardware and software, but let you choose your own connectors and enclosure rating. Bricks are typically cheaper per unit than pluggable modules, making sense for higher volume products, at the cost of more engineering work on connector selection, EMC, and mechanical integration.

Solder-on interfaces go a step further. They are smaller, rectangular modules soldered directly to the board. HMS points out that they can be roughly thirty percent smaller than pluggable bricks in height and depth, eliminate separate board-to-board connectors, and can be handled through automated assembly. They can store multiple Ethernet-based networks and switch them via firmware. The trade-offs are reliance on slower host interfaces such as SPI, difficulty replacing them late in production, and limited protocol coverage compared to full-feature modules.

Communication Chips and Full-Custom Designs

For very high-volume, cost-sensitive products, HMS advocates communication chips or full-custom designs. A communication chip is a network processor that runs protocol stacks and offloads networking from the host CPU. Renesas’ R‑IN devices, RX72M microcontrollers, and RZ MPUs, and Texas Instruments’ Sitara processors with PRU‑ICSS, fall into this category. They support multiple Industrial Ethernet and fieldbus protocols—including EtherCAT, Profinet, EtherNet/IP, CC‑Link IE, Modbus, and OPC UA—often by downloading different firmware or stacks.

TI’s documentation also highlights dedicated solutions such as the C2000 F28388D real-time MCU, which integrates EtherCAT for applications such as servo drives and robotics, where ultra-low latency and real-time control are decisive.

Building your own communication solution around chips or from scratch gives maximum control and can bring unit cost down, but you take on protocol stack integration, certification, and long-term maintenance. HMS cautions that as soon as you support more than one network, the internal effort and complexity grow quickly.

Comparing Module Approaches

The table below summarizes these architectures.

| Approach | What it is | Where it fits best | Main drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|

| External gateway | Stand-alone protocol converter | Retrofit, low volume, unmodifiable devices | Extra box, higher node cost |

| Embedded module | Pluggable board with full network interface | Multi-network OEM products, fast time-to-market | Higher unit price, fixed form factor |

| Pluggable brick | Embedded module on main PCB | Higher volume designs needing flexibility | More design work, still a distinct part |

| Solder-on interface | Compact embedded interface soldered to PCB | Very compact, automated assembly products | Harder to replace, narrower protocol support |

| Communication chip | Network processor with protocol stacks | High-volume devices, multi-network support | Requires strong networking and hardware expertise |

| Full-custom | Fully bespoke hardware and stacks | Very high-volume, single-network devices | Highest engineering and lifecycle burden |

Once you understand where your product sits in terms of volume, cost targets, and required protocol flexibility, this table usually narrows the field to one or two realistic approaches.

Selection Criteria That Actually Matter in the Field

Most data sheets look the same: speeds, connectors, some buzzwords about security. The research notes and real project experience suggest a more grounded set of criteria.

Protocol and Ecosystem Coverage

HMS and Renesas both stress that protocol support is not just a technical checkbox; it is a market access issue. HMS reports that more than twenty industrial network protocols still hold meaningful global share, with clear regional preferences such as Profinet in parts of Europe, EtherNet/IP in North America, and CC‑Link technologies in Japan and other parts of Asia.

Renesas shows that multi-protocol solutions can cover roughly seventy percent of major industrial networks with a single hardware platform when combined with the right stacks. Texas Instruments demonstrates a similar approach with Sitara processors and PRU‑ICSS firmware for EtherCAT, Profinet, EtherNet/IP, and other protocols.

For a communication module, this means you should check two things. First, whether it supports the protocols required by your immediate customers. Second, whether it gives you a credible path to reach other regions and ecosystems later without redesigning your hardware. Choosing a closed, single-protocol interface for a product that will ship globally often locks you out of future opportunities.

Performance, Determinism, and Topology

Mitsubishi Electric and Control Engineering emphasize that performance for industrial networking is not just about raw bandwidth. Determinism, cycle time, and topology support drive whether a module can handle motion control, synchronized drives, and safety functions.

Texas Instruments’ application material illustrates that many Industrial Ethernet applications run comfortably with cycle times around one millisecond. Profinet IRT can go down to tens of microseconds, and EtherCAT devices can forward frames with microsecond port-to-port latency. IO-Link Wireless, by contrast, is designed for millisecond-level latency suitable for sensors and actuators around a robot or machine.

Balluff’s discussion of Ethernet topologies also matters here. A module that only supports simple star topologies may be limiting if your plant standard is a ring or line topology down to I/O blocks. If your application needs high availability, ring redundancy and fast failover become key, and the module and its host must support the necessary protocol features.

When you evaluate a communication module, tie its performance claims back to your real needs. A low-volume batching skid may work happily with modest cycle times, while a multi-axis motion system or high-speed packaging line almost certainly will not.

Reliability, Redundancy, and Diagnostics

Motion Industrial, Moxa, and HMS all frame industrial networking as an availability problem as much as a throughput problem.

Moxa’s SMART framework calls out availability and robustness as first-class design dimensions. Redundant ring topologies, redundant devices, and even redundant wireless links are common where downtime costs real money. Industrial equipment faces temperature extremes, vibration, and poor power quality. Office-grade interfaces rarely survive these conditions.

HMS’ article on “best industrial network” highlights diagnostics and transparency as a critical evaluation criterion. Modern protocols such as Profinet and CIP-based networks include detailed device diagnostics, link health, and metadata. Modules and chips from vendors like HMS, Renesas, and TI typically expose these diagnostics through standard tools.

When assessing modules, look for support for network diagnostics, fast detection of link loss, and integration with management systems. A cheap module that goes dark without clear error reporting will cost you far more in lost time than the initial savings.

Security and Manageability

Moxa’s and Control Engineering’s security guidance, reinforced by HMS’ discussion of cybersecurity trends, is straightforward: industrial networks are now exposed to the same cyber threats as IT networks, and sometimes more.

Best practice involves multiple layers. At the network level, segmentation, VLANs, and secure gateways are used to isolate zones. At the protocol level, standards such as CIP Security for EtherNet/IP, Profinet Security classes, and secure variants of Modbus add encryption, authentication, and role-based access. At the management level, SNMP and other IT tools monitor device status and firmware across OT networks.

For communication modules, this translates into checking whether the module supports the secure versions of your target protocols and whether it gives you hooks to implement identity management and firmware updates. Mitsubishi Electric recommends support for standard IT tools such as SNMP when using Ethernet backbones, because they make monitoring and troubleshooting scalable.

If you choose a very basic interface without security features for a device that will be exposed to wider networks, you are building in a risk that will be expensive to fix later.

Physical Environment and Medium

Industrial networks are not deployed in server rooms; they run through hot, dusty, vibrating, and sometimes hazardous environments. Moxa and PUSR’s switch selection guidance, along with Omnitron’s industrial Ethernet and PoE material, underline the importance of physical design.

You need to consider operating temperature range, humidity, electromagnetic compatibility, enclosure and connector rating, and the transmission medium itself. Twisted-pair copper is suitable for short runs, typically up to about three hundred feet. Multimode fiber extends links to around one and one quarter miles, and single-mode fiber can reach roughly seventy-five miles, according to PUSR’s distance guidelines. Fiber is also preferred where you need galvanic isolation or must cross noisy or high-voltage areas.

Connectors matter as well. Mitsubishi Electric notes that although standard RJ45 is common, rugged circular connectors such as M12 or M8 are often mandatory in washdown or high-vibration environments.

When selecting a module or interface, ensure its physical characteristics match your worst-case application, not just the lab. An attractive low-cost module that cannot tolerate outdoor temperatures or panel vibration will fail exactly when you need it most.

Engineering Effort, Certification, and Lifecycle

HMS, Renesas, and TI all devote significant space to the engineering and certification burden of industrial protocols. Every protocol has its own conformance tests and certification bodies. Pre-certified modules and bricks offload much of that burden. Chips and custom designs give more flexibility but make you responsible for keeping up with evolving specifications.

Consider your team’s expertise. If you have a small development group and the device will need Profinet, EtherNet/IP, and EtherCAT over its lifetime, a certified multi-protocol module or brick from a specialist will likely reduce risk and time-to-market. If you are a large OEM shipping huge volumes of a single-network device, investing in an in-house communication chip design, perhaps based on Renesas or TI devices, can be justified.

Do not forget lifecycle. Industrial equipment often runs for decades. Ask vendors about their long-term support policies, component obsolescence plans, and how they handle protocol updates. A communication module that goes end-of-life five years into a twenty-year machine lifecycle will cause expensive redesigns.

Example Selection Walkthroughs

To make the criteria above concrete, it helps to look at typical project patterns and map them to module choices, using the guidance from the research sources.

Consider a brownfield integration where you need to bring an older Profibus and Modbus RTU skid into a new EtherNet/IP-centric plant network. Electrical Technology describes Profibus and Modbus as common device-level networks in legacy installations. The plant’s backbone, however, aligns with industrial Ethernet practices described by Control Engineering and Renesas. In this case, an external gateway is often the pragmatic choice. You map Profibus and Modbus registers to EtherNet/IP objects using a certified converter and leave the existing skid controls largely untouched. You avoid redesigning hardware that is already proven and focus on mapping and testing.

Now consider an OEM building a family of drives or compact controllers with global ambitions. HMS points out that supporting many networks through separate hardware variants quickly becomes a logistical nightmare. Renesas and TI both offer multi-protocol chips and modules precisely for this scenario. An embedded module or communication brick that can be loaded with different firmware for EtherNet/IP, Profinet, EtherCAT, or CC‑Link IE lets you build one mechanical platform and adapt to the customer’s preferred network through configuration or at most a module swap. As volumes grow and designs stabilize, you can migrate toward a communication chip solution to reduce unit cost while maintaining protocol flexibility.

Finally, imagine a robotics application with sensors on end-of-arm tooling that cannot tolerate cable flex fatigue. CoreTigo’s IO-Link Wireless description shows how you can give these sensors deterministic, low-latency communication within about sixty-five feet using a wireless master tied into the main industrial Ethernet network. Here, your “communication module” on the device side is an IO-Link Wireless interface, and on the controller side it may be an industrial Ethernet module on the master that presents the wireless devices as standard IO-Link or field I/O to the PLC. This arrangement keeps the control network deterministic while removing the mechanical risks of continuous flexing cable.

In each case, the right answer looks different because the problem is different. The common thread is aligning the module choice with the network landscape, performance needs, and lifecycle realities described in the research.

A Pragmatic Selection Process

Putting everything together, a consistent selection process emerges from the combined guidance of Mitsubishi Electric, Moxa, HMS, Renesas, TI, and others.

Begin by inventorying networks and constraints. Document which protocols exist at each level—fieldbus, Industrial Ethernet, wireless—and how deterministic and available they must be. Note environmental extremes, distance requirements, and any mobility or wireless needs.

Then define your integration scenario and volume. Decide whether you are retrofitting a handful of units or designing an OEM platform expected to ship in large numbers. This distinction strongly influences whether you should favor gateways, modules, or chip-level solutions.

Next, choose your target network technologies. Based on trends highlighted by Renesas and Nessum, you will likely converge on Industrial Ethernet for new control layers while respecting installed fieldbus devices and, in some cases, considering HD‑PLC or IO-Link Wireless to solve specific wiring or mobility problems. Aim for openness and multi-protocol capability where your market demands it, following the flexibility strategy advocated by HMS.

After that, select a module architecture and shortlist vendors. Use the pros and cons table for gateways, modules, bricks, solder-on interfaces, and chips, and match it to your volume, cost, and engineering capacity. Check protocol coverage, certification status, security features, and physical ratings against your earlier inventory.

Finally, prove it in a realistic testbed. The sources repeatedly emphasize management, diagnostics, and robustness. Build a small but representative network with your chosen module, including ring or line topologies if applicable, and test failover, power cycling, interference, and firmware update procedures. Treat this as a dress rehearsal for real plant conditions, not a quick bench check.

When you follow this kind of structured process, the communication module becomes another engineered part of the system rather than a last-minute patch for “getting onto the network.”

Closing

From the vantage point of a systems integrator and project partner, the best communication module is rarely the flashiest or the cheapest. It is the one that fits your real network landscape, respects the plant’s protocols and topologies, survives the environment, and can evolve with your customers’ needs.

If you treat network integration as strategic and let the criteria above drive your module selection, you greatly reduce the risk of surprises during commissioning and give your machines a communication backbone that will stand the test of time.

References

- https://www.electricaltechnology.org/2016/12/industrial-communication-networks-systems.html

- https://nessum.org/media/technology-blog/industrial-networking-solutions

- https://www.icpdas-usa.com/industrial-communication-protocols-a-practical-guide-to-modbus-ethernetip-and-profibus?srsltid=AfmBOorEmWRBC40VpHNyg1AVsZAvv0wttNBIB8YXGuf9nQnfV6GfRi2e

- http://pages.moxa.com/How-to-Approach-Ethernet-Based-Industrial-Networks.html

- https://www.controleng.com/industrial-networking-101-everything-you-need-to-know/

- https://www.coretigo.com/how-to-choose-the-right-industrial-wireless-solution/

- https://www.machinemetrics.com/connectivity/protocols

- https://ai.motion.com/a-guide-on-industrial-networking-and-connectivity-for-automation/

- https://www.omnitron-systems.com/blog/the-role-of-industrial-ethernet-and-poe-switches-in-industrial-automation-networks

- https://www.pusr.com/blog/Industrial-Switch-Selection-Guide-Applicable-to-Different-Industrial-Networking-Scenarios

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment