-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

How to Select a PLC Processor for High‑Speed Data Processing Requirements

High‑speed data processing is where PLC projects stop being simple wiring jobs and start becoming real engineering. Once you need millisecond‑level response, dense data acquisition, or tightly synchronized motion, the PLC processor choice becomes the difference between a clean startup and months of nuisance faults and dropped data.

As a systems integrator, I rarely see high‑speed issues caused by “bad” PLC brands. They almost always come down to misunderstood requirements, overloaded CPUs, or the wrong I/O and communications strategy wrapped around an otherwise decent processor. The good news is that you can avoid most of this by working through a disciplined selection process and knowing which processor specs really matter.

This article walks through how to select a PLC processor specifically for high‑speed data processing, drawing on practical guidance from vendors such as AutomationDirect, Maple Systems, Industrial Automation Co., Premier Automation, Control Engineering, and applied research on PLC CPU architecture from Silesian University of Technology. The aim is not theory for theory’s sake, but a workable method you can reuse on your next project.

What “High‑Speed” Really Means in PLC Terms

High‑speed in PLC language is not just a fast clock on a datasheet. Several intertwined behaviors define whether a processor is fast enough for your application.

A PLC operates in a continuous scan cycle. It repeatedly reads inputs, updates internal memory, executes the control program, and writes outputs. Maple Systems and Industrial Automation Co. both describe this loop as the core of PLC behavior, and its total duration is the scan time. For high‑speed manufacturing or precise real‑time control, that scan time must be short and predictable.

A research paper on PLC operation speed from Silesian University of Technology defines scan time as the time required to execute on the order of one thousand control instructions. That definition highlights an important point: scan time depends not only on CPU hardware but also on instruction mix and program size. Long, complex programs with heavy data handling and communications will push scan time up even with a fast processor.

AutomationDirect’s controller selection guidance notes that high‑speed applications often require controller scan times on the order of a few milliseconds or less. Control Engineering magazine adds that for motion and registration tasks, modern controllers often offload critical timing to high‑speed input and output modules that can monitor encoders at rates up to about one megahertz and switch outputs tens of thousands of times per second, independent of the main scan.

From a practical standpoint, high‑speed PLC applications usually share several characteristics. They carry a significant number of high‑frequency digital events such as registration sensors and encoders. They acquire analog signals at relatively high sample rates for quality or diagnostics. They require deterministic response, where a few missed scans can scrap product or trip safety interlocks. Finally, they often integrate with higher‑level systems, so the CPU must juggle field control, communications, and logging simultaneously.

When you say you have “high‑speed data processing requirements,” you are really saying you need the entire control stack—processor, I/O, communications, and software—to keep up with those behaviors under all conditions.

Start With a Structured Requirements Definition

Every serious vendor and integrator says the same thing in different words: do not start with a catalog page; start with a requirement sheet. AutomationDirect provides a “Considerations for Choosing a PLC” worksheet that functions as a checklist, and Premier Automation emphasizes letting the automation concept mature, even bench‑testing the process, before locking in hardware.

Clarify signals, data, and I/O

Begin by counting and characterizing everything the PLC must see and drive. AutomationDirect’s worksheet has you list discrete and analog devices and their signal types, because that directly determines the I/O count and modules your controller must support. A forum example from a control engineering site described a relay replacement project with around forty‑six digital inputs, forty‑five digital outputs, and a dozen analog channels each for inputs and outputs, all in a compact 19‑inch, 6U enclosure. That is not yet a “monster” system, but it is large enough that you cannot ignore I/O density and wiring constraints.

For high‑speed data processing, you must go a level deeper. A LinkedIn guide on selecting PLC hardware for high‑speed data acquisition recommends defining data type, volume, sampling rate, channel count, accuracy, and resolution. That means you do not simply list “ten analog inputs”; you specify that four of them need high‑speed sampling for vibration analysis at a particular rate, while others are slower temperature loops.

High‑speed features should be captured explicitly. AutomationDirect advises noting whether you need high‑speed counting, positioning, or a real‑time clock, because those specialty functions may not be available in the base CPU or standard I/O. Maple Systems calls out dedicated high‑speed counter inputs for encoders and PWM outputs for drive and servo control as criteria that must be matched to the application.

Quantify performance targets: scan time and cyclic load

Once you understand the signals, translate that into timing requirements. Ask how quickly the control system must react to a given change and how fresh data needs to be for decisions and logging.

The Silesian University research paper shows that in conventional scan‑based PLCs, fast control objects paired with large programs can lead to missed input changes. To mitigate this, they discuss both architectural improvements and programming techniques such as segmentation and interrupts. On commercial platforms, you instead work with scan time specifications, high‑priority tasks, and high‑speed modules, but the underlying concern is the same.

Premier Automation offers a very practical rule: do not run the processor flat out. In communication‑intensive applications, they recommend keeping peak cyclic CPU load around roughly sixty‑five percent and static cyclic load around about sixty percent. That leaves headroom for bursts of communications, additional logic, and abnormal conditions. If your requirements, when modeled, already push a candidate processor near full utilization, that is a red flag for a high‑speed system.

AutomationDirect’s worksheet suggests estimating program memory by applying a rule of thumb: about five words of program memory for each discrete device and around twenty‑five words per analog device for typical sequential applications, with complex logic needing more. When you combine that memory sizing with the performance targets above, you gain a useful first filter: eliminate any CPU family that cannot easily accommodate your anticipated program size and still maintain target scan times with comfortable CPU headroom.

Account for environment, power, and physical layout

Environment and power constraints often look like housekeeping items, but in high‑speed applications they can quietly degrade performance or stability.

AutomationDirect notes that typical controllers are designed for ambient temperatures around 32–130°F. Simcona, a panel manufacturer, reinforces that many PLC failures trace to moisture, extreme temperature, chemicals, electrical noise, dust, or vibration that exceed what the hardware and enclosure are rated for. If your system lives in a hot compressor room, on a vibrating machine base, or near large drives, you may need a processor and I/O family with higher environmental ratings and appropriate enclosures, otherwise your carefully selected high‑speed platform will slow down or fail intermittently under stress.

On the power side, Maple Systems highlights that PLCs are designed for specific supply voltages, commonly 24 or 48 VDC or 120 VAC, and that I/O circuits themselves may use 5, 12, or 24 VDC or 120 VAC. Simcona warns that an undersized or unstable supply can cause damage, memory loss, and degraded performance. High‑speed data acquisition amplifies this risk because data loss or false triggering will show up immediately when the processor or I/O rail droops. Matching processor and I/O voltage requirements to a solid, well‑engineered power scheme is a prerequisite for reliable high‑speed behavior.

Physical size and layout matter as well. The control.com example with a 19‑inch, 6U enclosure and D‑sub I/O harnessing illustrates how mechanical envelope constraints can narrow your options. Control panels for high‑speed machines also need considerations for heat dissipation and serviceability; Simcona points out that compact PLCs are good for tight spaces, but larger or modular systems may offer easier expansion and better airflow.

Processor Capabilities That Drive High‑Speed Performance

Once you have a clear picture of what you are asking the controller to do, it is time to scrutinize the processor itself. Several characteristics matter much more than generic “speed” claims.

CPU architecture and its impact

Maple Systems advises evaluating CPU speed, typically specified in megahertz or gigahertz, and architecture, such as 32‑bit versus 64‑bit, because both affect how rapidly the PLC can process instructions and how much data it can handle efficiently. For high‑speed data processing, a faster CPU with a more capable architecture will generally sustain shorter scan times and heavier math or data‑handling loads.

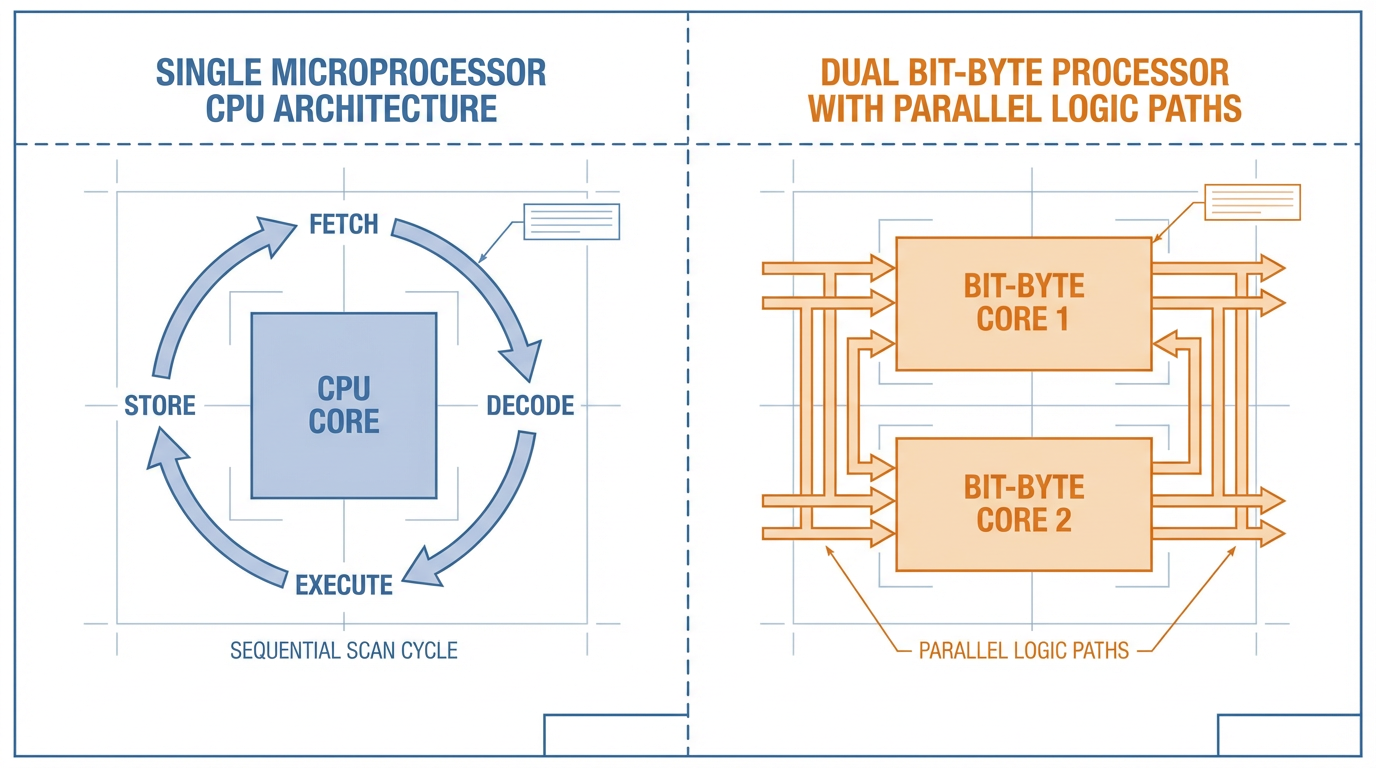

The academic work from Silesian University goes deeper, contrasting classic single microprocessor CPUs with bit‑byte dual‑processor architectures. In a bit‑byte design, a dedicated bit processor executes logical operations on discrete I/O, while a byte processor, usually a standard microprocessor, handles analog control, numerical processing, diagnostics, timers, and communications. By giving the fast but simple bit‑level work to specialized hardware and keeping heavier tasks on the byte processor, the architecture reduces latency on high‑frequency digital logic without bloating cost.

The same research discusses an even more aggressive approach: implementing control algorithms directly in reconfigurable hardware using FPGA technology. There, the control logic runs as fully parallel hardware rather than in a serial scan loop, and loading a new configuration into the FPGA plays a role similar to downloading a program into a PLC. Some modern products marketed as reconfigurable logic controllers follow this pattern. They can deliver extremely high performance, but they also demand more specialized engineering and tend to be justified only for the most demanding high‑speed applications.

For most industrial users, you will not be designing CPUs, but this research explains why controller families with strong bit‑level performance and modern CPU cores show better real‑world scan behavior at a given program size.

Scan time behavior and cyclic load

Maple Systems defines PLC scan time as the duration to read inputs, execute the control program, and update outputs, typically measured in milliseconds. They stress that shorter scan times allow the PLC to react more quickly to changes in input conditions, which is essential for high‑speed manufacturing and precise control.

Several factors push scan time up. Maple notes program complexity and communications load; Premier Automation adds that heavy communications traffic places significant demands on the CPU, and that running near maximum cyclic load degrades OPC server performance and overall throughput. The academic paper reinforces that excessive reliance on a single cyclic scan can cause fast input changes to be missed if the program is large.

In practice, when you assess a processor for high‑speed work, you should look for three things. First, vendor‑specified benchmark scan times for a representative program size. Second, tools for measuring actual CPU utilization during development and commissioning. Third, architectural features that help decouple time‑critical functions from the main scan, such as high‑priority tasks and dedicated high‑speed modules. Then apply Premier Automation’s rule of thumb on cyclic load and ensure your design keeps both average and peak CPU usage comfortably below saturation.

Program and data memory sizing

Maple Systems divides PLC memory into program memory, which stores the control logic, and data memory, which holds process variables such as timers, counters, and historical values. Larger, more complex systems require more of both, especially if you log or buffer data locally.

AutomationDirect’s worksheet gives a simple sizing guideline: estimate roughly five words of program memory for each discrete device and about twenty‑five words for each analog device for straightforward sequential logic, acknowledging that more intricate applications will need additional memory. They also highlight that if you intend to retain historical data such as measured values over long periods, the size of those data tables can drive CPU selection.

High‑speed data processing almost always increases data memory demand. You will store short‑term buffers, statistics, and possibly diagnostic traces. When comparing processors, favor those with generous data memory and straightforward mechanisms for expanding storage, whether through local memory expansion or external logging to removable media.

High‑Speed I/O, Motion, and Data Acquisition

Processor power is necessary but not sufficient. For many high‑speed applications, the I/O subsystem and specialized motion features are what decide whether you meet your timing budgets.

Digital high‑speed counters and registration

Maple Systems emphasizes that high‑speed counter inputs are required wherever you must precisely count high‑speed events, such as encoder pulses. These inputs are hardware‑assisted and designed to register pulses that might be too fast for the base CPU scan to capture reliably.

Control Engineering describes how dedicated high‑speed input and output modules, often called HSI and HSO modules, offload time‑critical tasks from the main CPU. High‑speed output modules generate pulse‑and‑direction commands for servo drives and other motion devices, while high‑speed input modules capture encoder feedback or registration sensor transitions independently of the controller’s cyclic scan.

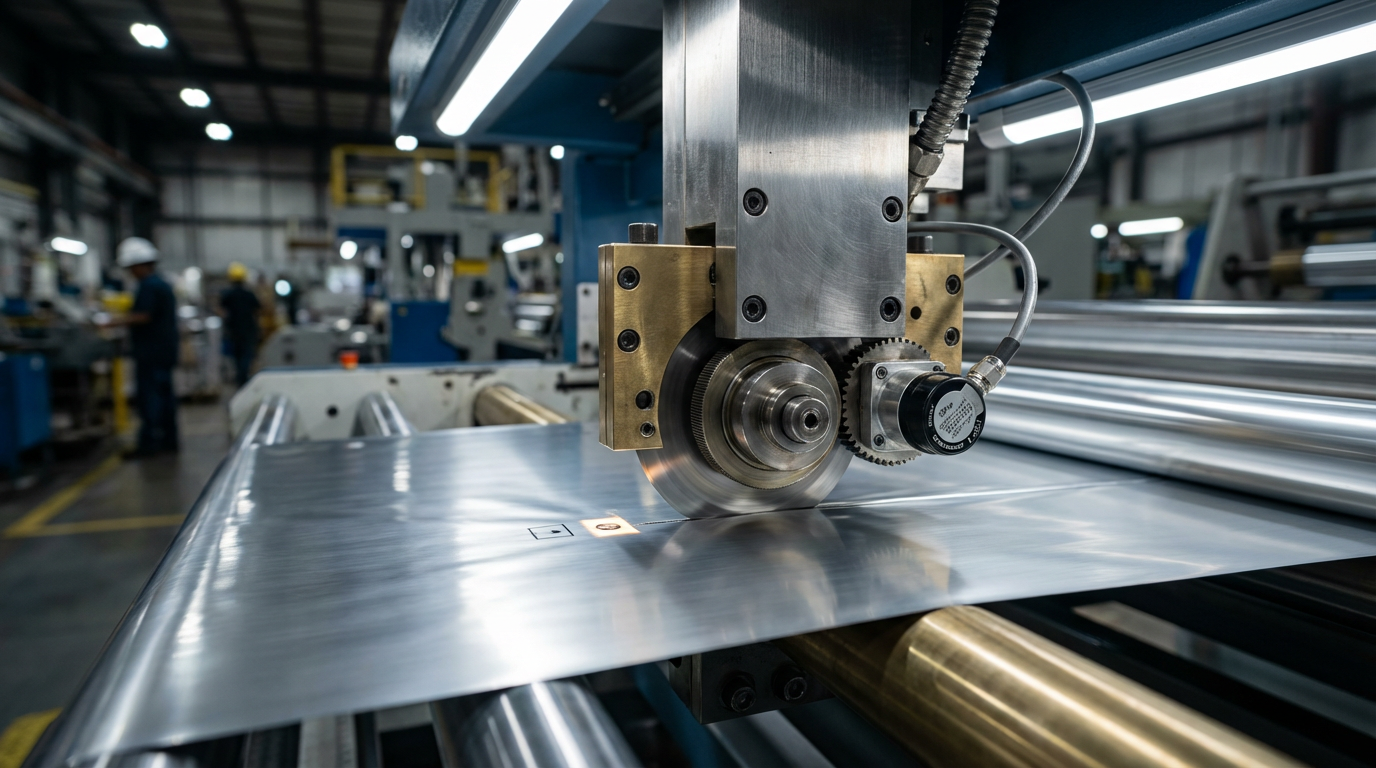

The same article outlines advanced functions such as registration, programmable drum switch, and programmable limit switch. These functions monitor high‑speed inputs like encoders at rates up to about one megahertz and control outputs tens of thousands of times per second, providing precise, repeatable motion timing that is effectively independent of scan‑time variability. For cut‑to‑length, stitching, or coordinated axis moves, that kind of hardware‑based timing is often the only practical way to meet tight tolerances.

The processor decision in these scenarios is less about raw CPU speed and more about choosing a controller family that supports the right high‑speed modules, integrates those modules tightly with the CPU, and provides the programming tools you need to configure registration and motion features safely.

Analog throughput, accuracy, and control

For analog‑heavy process applications, high‑speed data processing means achieving the right combination of sampling rate, resolution, and control algorithm performance.

The high‑speed hardware selection guide from LinkedIn recommends that you explicitly specify sampling rates, accuracy, and resolution for each analog channel set, along with total data volume. ACE, an automation supplier focused on process applications, points out that modern PLCs can now handle many process control tasks that historically required DCS systems. They cite flexible support for analog standards such as 4–20 mA and various voltage ranges, thermocouples, and RTDs, along with advanced programming features such as PID, feedforward, and dead‑time compensation.

For the processor, that implies you should look for efficient math performance and built‑in control function blocks so analog computations do not bog down the scan. Maple Systems suggests that structured text and function block diagram languages are particularly effective for complex mathematical operations and process control, while ACE emphasizes platforms that support multiple such languages and reusable code modules.

When you combine high‑frequency analog acquisition with advanced control and fast logging, memory throughput and CPU utilization become critical. It is not unusual in that context to combine a strong mid‑range CPU with carefully chosen analog I/O modules and thoughtful task scheduling rather than simply jumping to a high‑end processor.

Communications and Data Handling Under Load

High‑speed data processing is often less about manipulating bits and more about moving them. Communications and logging can easily dominate CPU cycles if you are not careful.

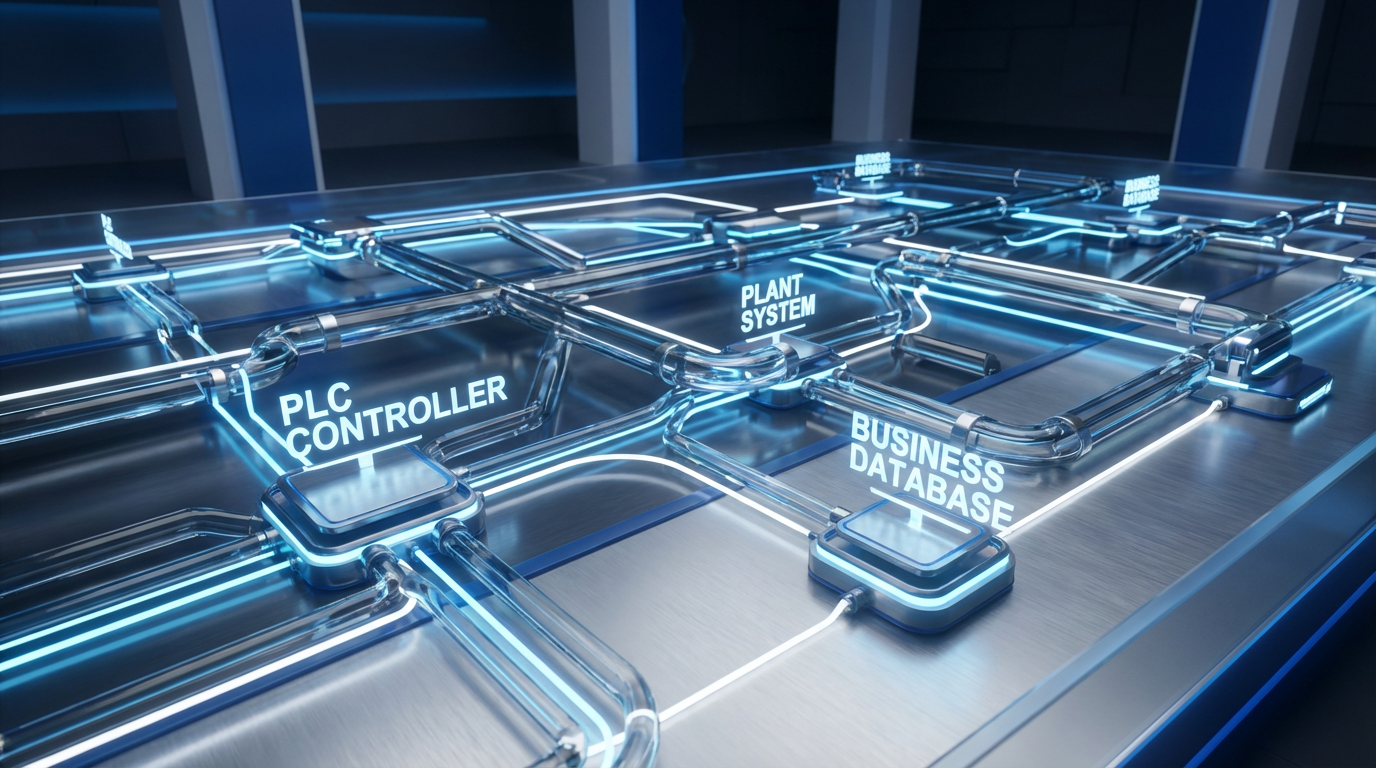

Industrial Automation Co. and multiple other sources point out that modern controllers must support Ethernet‑based protocols such as Ethernet/IP, Modbus TCP, and Profinet, as well as serial fieldbuses and OPC‑style interfaces. Premier Automation recommends choosing a controller line with a broad portfolio of communication modules and explicitly planning for IoT or Industry 4.0 integration rather than bolting it on later.

Control Engineering describes controllers that natively log data to USB or MicroSD media, often supporting storage capacities up to around thirty‑two gigabytes and logging at least dozens of tag values per event with flexible scheduling. They also show how controllers can connect to enterprise databases through OPC servers and ODBC‑compatible databases to exchange production data with business systems in near real time.

Each of these capabilities consumes CPU time and memory. High‑frequency logging, chatty network polling, and multiple simultaneous client connections will all increase cyclic load. Premier Automation’s advice to keep cyclic CPU utilization well below saturation is especially important here. When evaluating processors, ask what happens to scan time and CPU load when you enable all of the communication paths and logging features you actually intend to use, not just when the controller runs a benchmark program in isolation.

Remote access is another dimension. Control Engineering describes controllers that support remote monitoring over Wi‑Fi or cellular via smartphone or tablet apps, along with embedded web servers that expose diagnostics and data files. They strongly recommend protecting such access with firewalls, strong passwords, and encrypted VPN connections. Simcona adds that most security breaches in connected systems stem from human error and that controllers should support proper authentication and encryption.

From a processor selection standpoint, remote access features are valuable, but they also mean that the CPU must handle web server tasks, encryption, and additional communication threads. That is another reason to pick a processor family with enough performance and memory headroom rather than one that is just barely sufficient for the base control logic.

Matching Processor Class to Application Class

Not every high‑speed system needs a top‑of‑the‑line CPU or FPGA‑based controller. The AutomationDirect white paper on controller selection describes typical controller classes: micro‑PLCs handling on the order of tens of I/O, mid‑range systems covering hundreds of points, modular rack‑based systems scaling to thousands of I/O, and high‑end or PC‑based systems for very large, data‑intensive, or motion‑heavy applications.

For compact discrete skids with modest I/O and a few high‑speed counters, a modern micro or compact mid‑range PLC can be entirely adequate, provided it offers the necessary high‑speed I/O options. Industrial Automation Co. stresses that you should define control complexity, I/O types, required processing speed, and communication interfaces first; then a smaller controller often turns out to be both capable and economical.

For analog‑heavy unit operations such as small compressor systems or standalone process skids, ACE notes that a full DCS platform is frequently unnecessary and too expensive. A mid‑range PLC with good analog performance, built‑in PID and related control features, and robust communications is usually the best fit. The processor must be strong enough to execute control loops, handle diagnostics such as HART device data, and log performance metrics without eroding scan time.

At the top end, if you face extremely fast discrete logic, dense encoder feedback, and complex numeric calculations all at once, you may need to consider high‑end PLCs or specialized architectures. The Silesian University work on bit‑byte processors and FPGA‑based controllers illustrates one way vendors push the performance envelope: by running bit‑level logic and numeric tasks in parallel or mapping algorithms directly into hardware. When you see vendor literature referencing reconfigurable logic controllers or dual‑processor CPU modules, that is the kind of architecture they are drawing on.

In all cases, it is rarely wise to choose a processor that barely meets the immediate functional spec. Premier Automation advises designing with a forward‑looking mindset, selecting hardware that can evolve over at least the next several years. That is doubly important once you start exposing high‑speed data to plant and enterprise networks, where new analytics or compliance requirements can increase processing demands over time.

A Practical Selection Workflow You Can Reuse

Theory and datasheets are necessary, but high‑speed data processing projects are ultimately won or lost by process discipline. Combining the structured worksheet approach from AutomationDirect with best practices from Premier Automation and others gives a workable method.

First, capture requirements in writing. Use a worksheet or spreadsheet to record whether the system is new or an upgrade, noting any existing devices, HMIs, VFDs, and protocols that must remain compatible. List the full inventory of discrete and analog devices, including which ones require high‑speed counting, fast analog sampling, or special functions such as PID. Document environmental constraints, power availability, enclosure limits, and any regulatory codes that affect controller selection.

Next, estimate program size and data volume. Apply the simple memory rules from AutomationDirect as a starting point, then adjust for complexity if you know you will have substantial data handling or advanced algorithms. Estimate the volume of data to be logged and the retention period to understand whether you can rely on internal memory and removable media, or whether you need structured integration with external databases as described in Control Engineering.

Then, translate process dynamics into timing and performance targets. For each critical sequence or control loop, ask what the maximum acceptable response time is, and from that derive an approximate scan time requirement. For high‑speed analog data acquisition, define target sampling intervals. Use these to screen candidate CPUs, looking at their published scan performance and available high‑speed I/O and motion modules.

After you have a shortlist of processor families, consider communications and integration. Verify that the CPUs support all required protocols, such as Ethernet/IP, Modbus TCP, Profinet, and any serial or fieldbus connections noted in your requirements. Ensure that the communication ports and modules available in the family can handle concurrent tasks like SCADA connectivity, peer‑to‑peer links, and historian data transfer. Premier Automation suggests validating communication requirements early because adding communication modules late can be more costly than selecting a more suitable CPU up front.

At this point, it is worth creating at least a bench‑top prototype for demanding high‑speed applications. Premier Automation explicitly recommends bench testing to validate and refine project requirements before finalizing controller selection. With a development chassis, representative I/O, and simulated or real signals, you can measure actual scan times, CPU load, and communication behavior using the vendor’s diagnostics. That is the most reliable way to confirm that the processor behaves as expected before you commit to a full panel build.

Finally, evaluate lifecycle and support factors. Industrial Automation Co., Simcona, and others all emphasize that vendor support, documentation, and training resources are as important as raw specs. Assess whether the controller platform offers clear manuals, example code, diagnostics, and local or remote technical support. Consider total cost of ownership, including software licensing, engineering time, training, maintenance, and potential downtime, rather than focusing only on purchase price.

Example Scenario Comparison

To pull these ideas together, it helps to see how different requirements lead to different processor emphases. The following table uses ranges and qualitative descriptions drawn from the referenced sources.

| Scenario | Processing and data demands | Processor focus | Supporting features to prioritize |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compact discrete machine with a few encoders | Short reaction times to sensors, high‑speed counting on limited points, modest logging | Mid‑range or even micro PLC with strong bit‑level performance and adequate CPU headroom | Dedicated high‑speed counter inputs, PWM outputs, basic data logging, support for required Ethernet protocols |

| Analog‑heavy process skid | Multiple PID loops, moderate‑speed analog sampling, continuous operation with diagnostics | Mid‑range PLC with efficient math, adequate data memory, and built‑in control function blocks | High‑quality analog I/O, advanced control blocks (PID, feedforward), HART or similar diagnostics, online changes |

| High‑speed motion and registration line | Tight position control, encoder rates near upper limits, precise cut‑to‑length or stitching | Higher‑performance PLC family with powerful CPU and motion‑oriented high‑speed I/O modules or reconfigurable logic | HSO/HSI modules, registration functions, PDS/PLS features, priority tasks for motion, large local logging storage |

| Data‑intensive, networked production cell | Significant local control plus heavy logging and enterprise connectivity | Processor with strong communications performance and generous memory, kept at moderate cyclic load as Premier suggests | Multiple Ethernet ports or modules, OPC or database connectors, USB/MicroSD logging, embedded web server, VPN‑friendly security |

The goal is not to prescribe specific models, but to show how the same disciplined thinking changes what you look for in a processor depending on the dominant demand.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls in High‑Speed Processor Selection

Several recurring mistakes show up across vendor guidance and forum discussions.

A very common error is sizing the CPU based only on I/O count. AutomationDirect’s worksheet and Industrial Automation Co.’s advice both insist on factoring in application complexity, special functions, and communications. A system with modest I/O but heavy data handling or remote connectivity can stress a small CPU more than a simple system with far more points.

Another is underestimating communications and logging. Premier Automation highlights how communication‑intensive applications push cyclic load up and recommends explicit CPU load limits. Control Engineering demonstrates just how much data modern controllers can log locally and exchange with databases; if you design all of that on paper and then choose the smallest processor, you will inevitably see scan time drift and unpredictable behavior once the system goes live.

Ignoring environment and power is also surprisingly common. Simcona notes that typical PLC operating ranges around 32–130°F are often exceeded in real plants, and Maple Systems explains how mismatched supply and I/O voltages can lead to noise problems and unreliable operation. High‑speed applications are unforgiving of marginal conditions; design the environment and power for stability first.

Over‑specifying software features and under‑specifying maintainability is another trap. Simcona observes that up to around eighty percent of software features on some platforms are rarely used. Maple Systems and Industrial Automation Co. both emphasize choosing programming languages and tools that your team is comfortable with, along with features like online editing, simulation, diagnostics, and good documentation. The fanciest motion or data functions do not help if your technicians cannot understand the code under pressure.

Finally, many teams treat CPU selection as a one‑time purchase decision rather than a lifecycle choice. Premier Automation encourages designers to weigh flexibility, support, quality, and cost over a five‑year horizon. Industrial Automation Co. and Simcona both stress vendor reputation and long‑term availability. For high‑speed data processing systems that will be deeply integrated into plant and business networks, stability of the platform and vendor ecosystem is a major risk factor, not an afterthought.

Short FAQ

Q: How fast should my PLC scan time be for a high‑speed application? A: Vendor guidance indicates that high‑speed applications often need scan times on the order of a few milliseconds or less, but the exact requirement depends on your process. Start from your fastest required reaction or sampling interval, then verify through testing that the chosen processor maintains that scan time with all logic, communications, and logging enabled, while keeping cyclic CPU load in the moderate range recommended by Premier Automation.

Q: When do I really need FPGA‑based or bit‑byte CPU architectures? A: Research from Silesian University of Technology shows that dual‑processor bit‑byte CPUs and FPGA‑based controllers can dramatically improve performance by executing bit‑level logic and numeric tasks in parallel. In practice, these architectures are most justified when you face extremely fast discrete events, dense calculations, or both, and conventional scan‑based PLCs with high‑speed modules still cannot meet your timing or determinism requirements.

Q: Is it safer to simply buy the biggest PLC processor available? A: Bigger is not automatically safer. Industrial Automation Co., Maple Systems, and Simcona all emphasize matching processor capabilities to clearly defined requirements and considering total cost of ownership. Oversized processors can increase hardware and licensing costs and may tempt over‑complicated designs, while undersized processors risk instability. A structured requirement capture, realistic load estimates, and prototype testing are more reliable than blanket over‑sizing.

Selecting a PLC processor for high‑speed data processing is ultimately a risk‑management exercise. If you treat it as such—by rigorously defining requirements, respecting what scan time and CPU load really mean, and choosing a platform with the right I/O, communications, and lifecycle support—you will be a partner your operations and production teams can trust when the line is running at full speed.

References

- https://www.academia.edu/96108217/REMARKS_ON_IMPROVING_OF_OPERATION_SPEED_OF_THE_PLCs

- https://admisiones.unicah.edu/virtual-library/GGcvLV/5OK106/introduction_to__programmable-logic-controllers.pdf

- https://lms-kjsce.somaiya.edu/pluginfile.php/96172/mod_resource/content/1/MODULE_1.pdf

- https://www.plctalk.net/forums/threads/how-to-choose-the-right-plc.9219/

- https://www.empoweredautomation.com/best-practices-for-implementing-automation-plc-solutions

- https://www.newark.com/a-comprehensive-guide-on-programmable-logic-controllers-trc-ar

- https://www.ace-net.com/blog/how-to-select-the-perfect-plc-for-your-process-application-key-factors-to-consider?hsLang=en

- https://support.automationdirect.com/docs/worksheet_guidelines.html

- https://www.controleng.com/industrial-controller-selection-look-beyond-the-basics/

- https://maplesystems.com/10-things-to-consider-when-choosing-new-plc/?srsltid=AfmBOooe9D8oN6_8PO3h_jDOI64a2Xsmr3qYvxmK6_wkQKdDBNDNkCeW

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment