-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Regenerative Drive Capability for Energy Recovery Applications

Why Regenerative Drives Matter Now

Walk into any modern plant today and you will hear the same two pressures: cut energy costs and hit aggressive sustainability targets, without compromising uptime. Variable speed drives and high‑efficiency motors are already standard in new projects. The next logical step is to stop throwing away braking energy as heat and start treating it as a usable resource. That is exactly what regenerative drive capability delivers.

Vendors such as Ameronics, ABB, Siemens, Danfoss, KEB, and others have spent the last couple of decades maturing regenerative drive technology in real industrial environments. At the same time, the broader electrification world has proven the physics: electric vehicles, rail systems, and metros consistently show double‑digit percentage energy savings by recovering braking energy instead of burning it off in resistors. Studies summarized by EV engineering sources report regenerative braking efficiencies around sixty to seventy percent at the system level, with real‑world energy recovery often in the fifteen to thirty percent range on favorable duty cycles. In building systems, IEEE work on elevators notes that elevators can account for up to about fifteen percent of energy use in high‑rise buildings, which is why elevator manufacturers like Mitsubishi, Otis, and others now offer regenerative options as standard or recommended packages.

From a systems integrator’s perspective, this is no longer experimental technology. Regenerative capability is a practical tool that can be engineered into drives, hoists, elevators, conveyors, test rigs, and even DC microgrids. The real question is not whether regeneration works, but where it makes sense, how to implement it correctly, and what pitfalls to avoid.

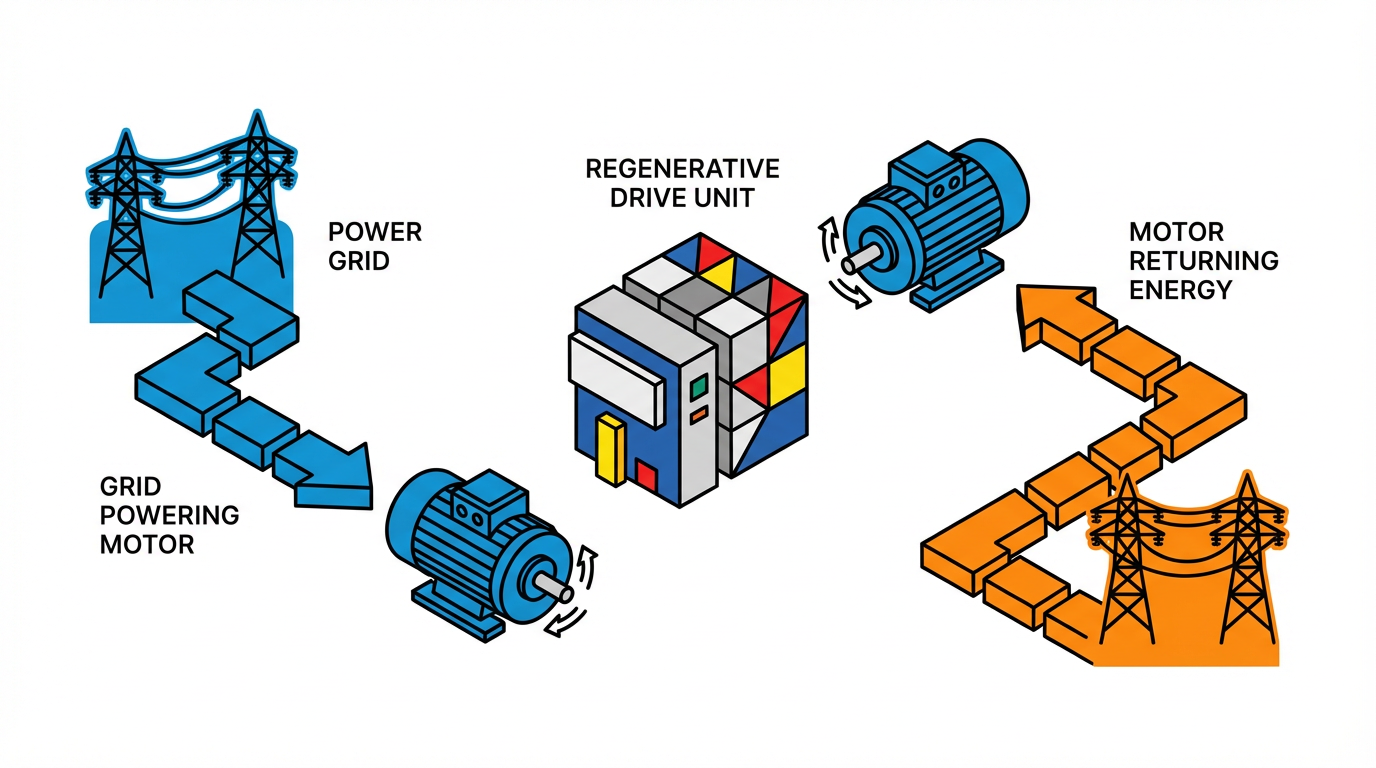

What A Regenerative Drive Really Does

A regenerative drive is, at its core, a motor controller that allows energy to flow both ways. In motoring mode, it behaves like a standard drive, taking electrical power from the supply and delivering controlled voltage and frequency (or DC output) to the motor. In generating mode, when the motor is driven by the load instead of the other way around, the drive takes that mechanical energy, converts it back into electrical power, and sends it somewhere useful instead of into a resistor bank.

Ameronics describes it simply in the context of DC motor control: when a DC motor slows down or reverses, a regenerative drive lets electrical energy flow back into the power supply rather than wasting it as heat. Their RegenCore series, for example, takes 115 or 230 VAC in and delivers controlled 0–90 or 0–180 VDC out to the motor, with full regenerative braking capability. That regenerative action is not limited to DC drives. ABB’s regenerative AC drives and Siemens SINAMICS drives work on the same principle, using an active front end or regenerative module to push power back onto the AC line or a DC bus whenever the drive decelerates the motor.

Phoenix Contact, in its energy recovery discussions, frames this more broadly: energy recovery is any process that captures energy that would otherwise be wasted and converts it into useful electricity or heat. In drive systems, the wasted energy is normally braking energy. In a conventional setup that energy is dumped into braking resistors and turned into heat that the HVAC system must remove. In a regenerative setup, it becomes usable power that other equipment can consume.

The key point is that a regenerative drive does not magically create free energy. It simply stops you from throwing away energy you already paid for, and it does so in a controlled, grid‑friendly way.

Braking Resistors Versus Regenerative Drives

Most plants already use some form of dynamic braking. The question is whether that braking should be handled by resistors or by regeneration back to the supply or DC bus.

Traditional Braking Resistors: Simple and Wasteful

Standard VFDs and DC drives with diode rectifiers behave like a one‑way street. Power can flow from the grid to the motor, but not back. When a crane lowers a load, or a conveyor decelerates a heavy product stream, the motor behaves as a generator and pushes energy back toward the DC bus. Because the rectifier cannot pass that energy upstream, the DC bus voltage rises. To protect the drive, a braking chopper switches on and sends that energy into resistor banks, which convert it to heat.

KEB America highlights the problems with this approach in crane and hoist applications. Braking resistors run very hot, which is a significant ignition risk in hazardous or explosion‑proof environments with flammable gases or dust. Mounting resistors outside the explosion‑proof enclosure adds complexity, requires long cable runs, and undermines the certification of the enclosure itself. Even in nonhazardous plants, the heat from resistors increases room temperature, forcing the HVAC system to work harder.

Resistors are simple and cheap to install, but by design they waste all of the braking energy and create a thermal management problem.

Full Regenerative Drives and Active Front Ends

Regenerative drives solve that problem by using an active supply unit instead of a simple diode bridge. ABB notes that its regenerative drives integrate all components required for regeneration inside the drive. The active front end allows full power flow in both directions, so the drive can push energy back into the supply network whenever the motor is generating.

Several side benefits come with that active front end. Because the supply unit is fully controlled, it can minimize harmonics and maintain a near‑unity power factor, improving overall power quality. It also eliminates bulky external braking devices in many cases, freeing panel space. Siemens points out that using variable frequency drives with energy recovery functions allows users to optimize both efficiency and sustainability, not just speed control.

OnDrive’s experience deploying regenerative Yaskawa‑based systems since the late nineteen‑nineties confirms that this is mature, field‑proven technology, not a lab curiosity.

Common DC Bus and DC Grids

Not all recovered energy needs to go back to the AC line. In many automation systems it is more efficient to keep energy on a DC bus, where motoring drives, DC link capacitors, or stationary storage can absorb it. Phoenix Contact’s All Electric Society vision explains that DC infrastructures make it easier for loads and sources to exchange energy directly without repeated AC/DC conversion steps, reducing losses and simplifying energy recovery.

In such architectures, one drive’s braking energy can immediately power another drive that is accelerating. Regenerative modules or drives maintain DC bus voltage within limits and only export energy to the AC grid when there is a net surplus. This approach is especially attractive in multi‑axis robotics, transfer lines, and process lines where motoring and braking axes operate simultaneously.

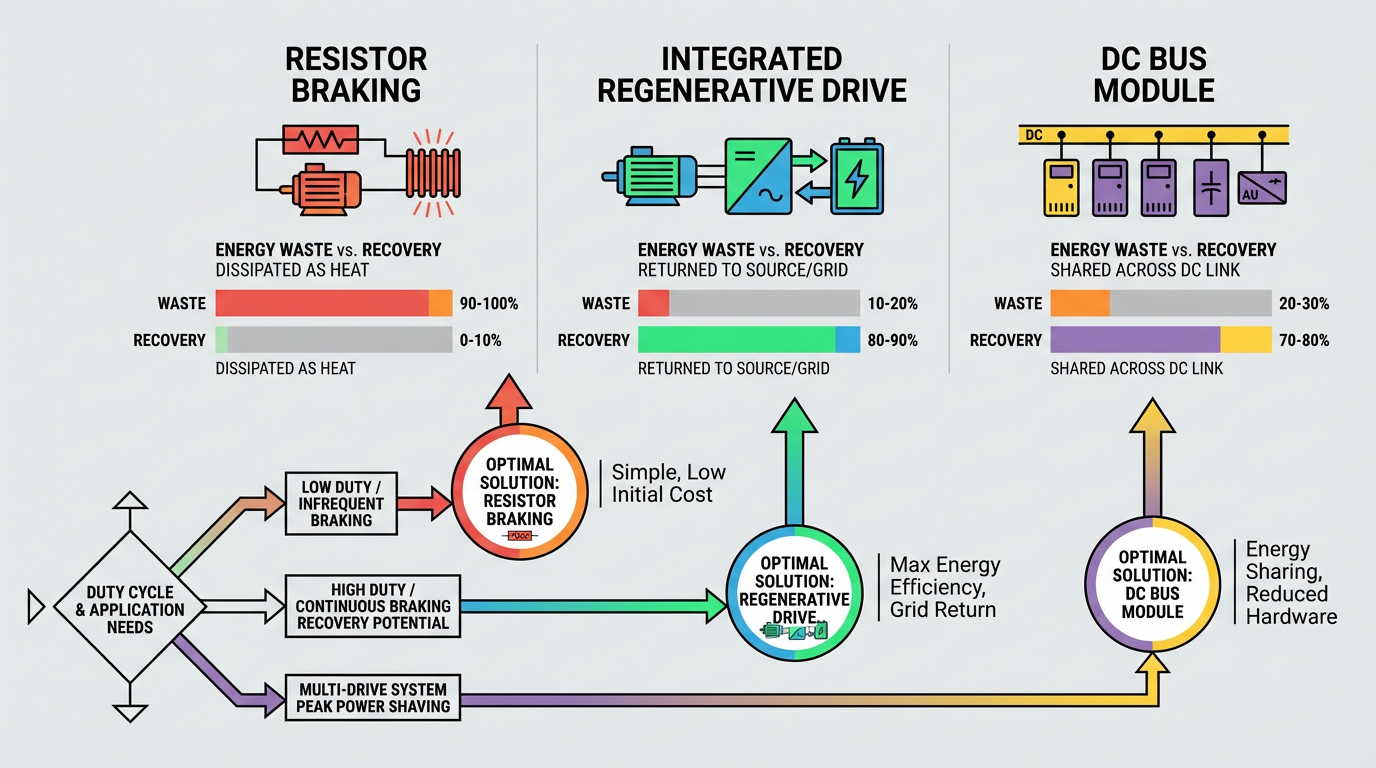

Comparing Approaches

The practical differences between these approaches can be summarized as follows.

| Approach | What Happens to Braking Energy | Typical Use Cases | Main Advantages | Main Tradeoffs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braking resistors | Converted to heat in resistor banks | Small drives, simple conveyors, low duty braking | Low first cost, simple design | Wasted energy, added heat load, safety issues in hazardous zones |

| Integrated regenerative drive | Pushed back to AC supply with active front end and power quality control | Standalone elevators, cranes, test rigs, large drives | Energy savings, less heat, improved harmonics and power factor | Higher drive cost, more complex commissioning |

| Regenerative module on DC bus | Shared across drives on common DC bus, surplus can feed AC grid | Multi‑axis systems, DC microgrids, mixed motoring and braking | Maximizes internal energy reuse, scalable architectures | Requires DC bus design, coordination, sometimes storage |

The right choice depends on duty cycle, safety requirements, available electrical infrastructure, and business priorities.

Where Regenerative Drives Pay Off

In theory, any driven system that regularly slows down or lowers a load can benefit from regeneration. In practice, some applications are much better candidates than others.

Elevators are a classic example. Darwin Motion’s work on elevator regenerative drives explains the core principle: when a heavy car travels down or a light car travels up, gravity helps, the motor behaves as a generator, and the drive can feed electrical power back into the building. IEEE studies on regenerative elevator drives show that even recovering a modest fraction of that gravitational energy yields measurable energy savings. Because elevators can account for a double‑digit share of a high‑rise building’s electricity use, these savings have outsized impact. Mitsubishi’s energy‑efficient regenerative drive option for its Diamond Trac machine‑room‑less elevators is marketed not only for energy savings but also for reduced heat in the hoistway, which in turn can ease cooling system requirements.

Cranes and hoists are another prime candidate. KEB’s work with regenerative drives in cranes highlights the frequent switching between lifting and lowering. During lowering, the load drives the motor, sending energy back toward the drive. Instead of routing that energy into extremely hot braking resistors, their R6 regenerative unit returns it to the building supply while staying inside an explosion‑proof enclosure. One example from their analysis shows that in a ten horsepower hoist, after mechanical losses, roughly forty‑plus percent of the input power can appear as recoverable regenerative power during lowering. That figure will vary widely by drivetrain efficiency and duty cycle, but it illustrates how much energy is typically being burned in resistors today.

Conveyor and packaging systems often have less dramatic loads but very frequent start–stop cycles. Ameronics explicitly calls out conveyors and packaging systems as valuable use cases for regenerative DC motor drives. Downhill conveyors, accumulation conveyors with controlled deceleration, and high‑throughput sortation systems are particularly good candidates because they produce repeated braking events throughout each shift.

Robotics and servo‑driven automation lines see similar patterns. OnDrive notes that regenerative braking is beneficial in multi‑axis robotics and automated environments where precise motion and high availability are critical. In those systems, some axes accelerate while others decelerate, so a common DC bus with regenerative capability allows local energy sharing, reducing net power drawn from the grid.

Test stands, centrifuges, and winders or unwinders round out the list. Danfoss describes how regenerative drive solutions excel where heavy or frequent braking is inherent, such as downhill conveyors, centrifuges, and test benches that spin up large inertias and then bring them down again. In such cases, the braking energy is a large share of the duty cycle, which is exactly where regeneration yields the strongest payback.

Across these applications, the pattern is clear: frequent or heavy braking plus sizable loads equals strong regeneration potential.

Quantifying The Benefits

It is natural to ask how much energy a regenerative drive can actually save. There is no single number, because the answer depends on the process, but data from transportation and elevator studies give useful boundaries.

Electric vehicle research provides one of the clearest pictures. EV engineering sources report that regenerative braking systems often convert about sixty to seventy percent of captured kinetic energy into stored electrical energy under ideal conditions. The actual share of a vehicle’s total kinetic energy that is recovered in real driving tends to land somewhere between fifteen and thirty percent on routes with regular deceleration and downhill segments, and it can fall below ten percent on flat routes with steady cruising. Separate automotive analyses show that regenerative braking can extend driving range by roughly ten to thirty percent in stop‑and‑go urban conditions, and that city driving can see efficiency gains up to around thirty percent compared with friction‑brake‑only operation.

Rail systems tell a similar story at larger scale. Data summarized in public railway sources indicates that British Rail Class 390 trainsets saved around seventeen percent of traction energy through regenerative braking, and electric multiple units on systems such as Caltrain have reported recapturing roughly twenty‑plus percent of consumed energy and feeding it back to the grid. Urban metros go even further in aggregate. The Delhi Metro, for example, regenerated on the order of a hundred thousand megawatt‑hours of electricity over several years, avoiding tens of thousands of tons of carbon dioxide emissions.

While these figures come from transportation rather than factories, the underlying physics is identical. In any system where braking energy represents a substantial share of the duty cycle, capturing even a fraction of that energy yields double‑digit percentage reductions in drive energy use.

Elevator‑specific studies back this up. IEEE analyses of regenerative elevator drives in real buildings show that even recovering a relatively small slice of kinetic energy can noticeably improve system efficiency. Manufacturer literature for regenerative elevator packages commonly reports double‑digit percentage reductions in elevator energy use compared with non‑regenerative drives, often on the order of roughly one‑third less net energy consumption, depending on traffic patterns and building configuration.

In cranes and hoists, KEB’s example calculation, which recovers about forty‑plus percent of the hoist’s input power during lowering after accounting for losses, demonstrates that there can be a very large pool of energy to recover in gravity‑dominated processes. Their work also shows that upgrading mechanical components, such as switching from less efficient worm gear reducers to helical bevel gears, can boost regenerative power by as much as forty percent and shorten payback periods.

There are benefits beyond raw kilowatt‑hours. Because braking energy is reused rather than turned into heat, regenerative systems reduce the thermal burden on electrical rooms and hoistways. ABB notes that this often allows smaller or simpler cooling systems and more compact installations. Mitsubishi emphasizes the reduced heating of the hoistway area for its regenerative elevators. Fewer hot braking resistors also improve safety and reliability in dusty or hazardous environments, as KEB points out.

Finally, regenerative braking reduces mechanical and thermal stress on brakes. Automotive and EV studies consistently report significantly lower wear on friction brakes because they are used mainly for low‑speed stopping and emergencies. The same effect appears in elevators and industrial machinery: regenerative drives handle much of the routine deceleration, so mechanical brakes remain cooler and last longer.

Taken together, the picture is clear. When the duty cycle is right, regenerative drives can deliver meaningful energy savings, reduce cooling costs, improve safety and power quality, and extend equipment life.

Design Considerations and Common Pitfalls

Despite the benefits, regenerative capability is not a universal answer. Implemented poorly, it can create new problems. Implemented correctly, it becomes a very reliable part of the control system. Several design considerations deserve attention.

Duty Cycle and Energy Profile

The most important question is how much braking energy is really available to recover. Danfoss explicitly recommends evaluating the duty cycle and amount of braking energy when deciding between simple braking resistors and regenerative solutions. EV and hydrogen vehicle studies, such as the MDPI review on energy recovery systems, show that recovered energy depends heavily on speed, mass, operating conditions, and driver behavior. In industrial terms, that translates to load weight, velocity, frequency of starts and stops, and the shape of the speed profile.

If a conveyor runs at steady speed most of the day and only stops a few times per shift, the available regenerative energy may be too small to justify the added cost of regeneration. If a crane continuously lifts and lowers heavy loads, or if a test stand repeatedly ramps large inertias up and down, regeneration is likely to pay back quickly.

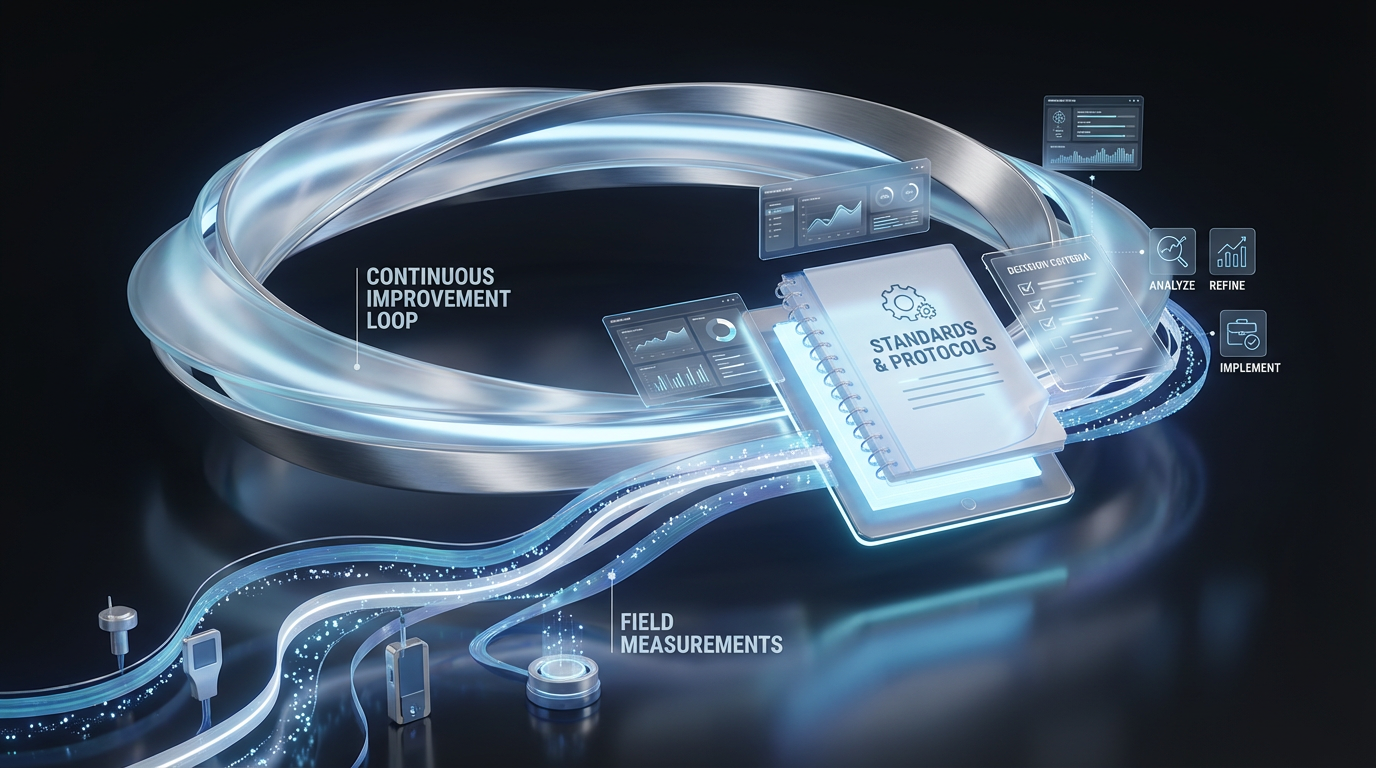

Where possible, measuring real power flows with a power analyzer before and after a trial installation, as described in regenerative elevator research, gives a solid basis for an investment decision.

In projects where measurement is not feasible up front, careful modeling and conservative assumptions are essential.

Electrical Infrastructure and Power Quality

Recovered energy needs somewhere to go. In a large factory with a healthy mix of loads, pushing energy back into the AC bus is usually straightforward. In smaller facilities, on weak utility feeders, or on generator‑supplied systems, designers must consider how the supply will react to exported power.

ABB and OnDrive emphasize that modern regenerative drives include active front ends that not only manage bidirectional power flow but also clean up harmonics and control power factor. Mitsubishi notes that its regenerative elevator drives aim to return clean power that complies with standards such as IEEE 519. Siemens recommends using energy recovery functions within its SINAMICS drives to improve both efficiency and sustainability. These capabilities reduce the risk of upsetting other equipment on the same bus.

However, some systems still need a backup energy sink for situations where the grid or DC bus cannot accept regenerated power. Automotive experience with batteries at full charge, such as Accelera’s work on managing regenerative energy at one hundred percent state of charge, is a useful analogy. When the battery cannot take more energy, their integrated brake chopper and resistor package diverts excess energy into liquid‑cooled resistors to protect the system. In industrial drives, a similar concept applies. Even with regenerative capability, it is often wise to keep a controlled braking resistor as a safety valve to handle rare but critical conditions where the line cannot absorb more power.

Thermal and Mechanical Constraints

Regenerative braking does not eliminate the need for mechanical brakes. Work on electric vehicles and regenerative braking consistently shows that regeneration alone cannot safely stop a system in all conditions. Braking effect falls off at low speeds, and mechanical brakes remain essential for emergency stops, holding, and low‑speed precision.

The same is true for cranes, hoists, and elevators. Regenerative torque is limited by motor capability, drive ratings, and power quality constraints. Mechanical brakes and safety gear must still be sized for worst‑case static loads and emergency scenarios. In some hazardous applications, codes or internal standards may forbid relying on regenerative braking for safety functions.

Mechanical design also has a strong influence on regenerative performance. KEB’s example of switching to more efficient gearboxes illustrates how mechanical losses directly reduce recoverable energy. If the drivetrain wastes most of the energy as friction, the regenerative system will have less power to capture.

Controls, Safety, and Ride Quality

Regenerative drives are not just power electronics; they are part of the motion control system. Automotive work on blended braking, and research on four‑wheel independent drive vehicles, shows that coordinating regenerative and friction braking is a nontrivial controls problem. The system must respect traction limits, maintain stability, and deliver a predictable, comfortable feel.

Elevator and crane drives must do the same. Deceleration ramps, jerk limits, and ride comfort requirements often constrain how aggressively regenerative torque can be applied. For elevators, comfortable, predictable deceleration matters as much as energy savings. For cranes and hoists, safe load handling and positioning come first.

From a safety perspective, emergency stops, fault responses, and power loss scenarios must be thoroughly engineered. The system should never depend on regenerative braking alone to protect people or equipment.

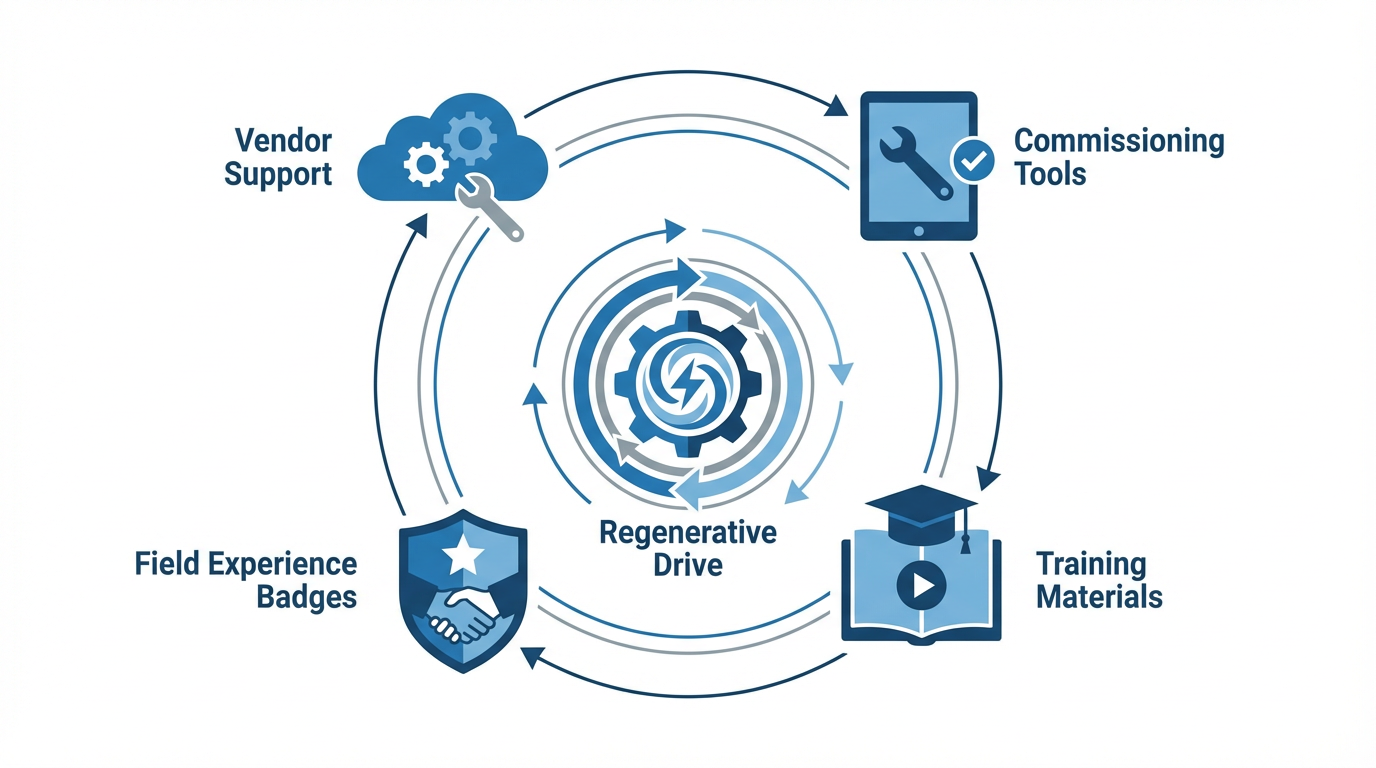

Complexity and Skills

Regenerative capability introduces some complexity. Commissioning an integrated regenerative drive, or a DC bus with multiple drives and a regeneration module, requires more engineering effort than adding a simple braking resistor. On the other hand, the technology is no longer exotic. OnDrive reports more than two decades of field experience with regenerative systems. KEB’s regenerative drives have been used by crane manufacturers such as Potain for over twenty years. Major players like ABB, Siemens, and Danfoss provide tools and guidance that simplify design and commissioning.

The practical challenge is making sure your team or your chosen integrator understands how to model duty cycles, coordinate controls, and handle power quality issues. When that expertise is in place, regenerative drives are as reliable as conventional drives.

How To Evaluate A Regenerative Drive Project

In real projects, the decision to add regenerative capability usually comes down to a structured evaluation rather than a gut feel.

The first step is to identify where energy is currently being burned off in resistors or mechanical brakes. Look for elevators, cranes, hoists, downhill conveyors, high‑inertia test rigs, and servo‑driven systems with aggressive deceleration profiles. Once candidates are identified, estimate or measure how often braking occurs, how much power is involved, and how long each braking event lasts.

The second step is to estimate the energy recovery potential. Use vendor tools or simple calculations based on load mass, speed, and duty cycle. Transportation data suggests that in brake‑heavy duty cycles, capturing fifteen to thirty percent of drive energy is realistic when regeneration is properly applied. In gravity‑dominated applications, examples like KEB’s hoist calculation show that the fraction can be even higher.

The third step is to check electrical integration. Confirm that the facility power system, upstream protection, and any generators can accept regenerated power. Decide whether recovered energy will be kept on a DC bus to feed other loads, returned to the AC grid, or a combination of both. If power quality is a concern, select regenerative drives or modules with integrated harmonic mitigation and power factor control, as ABB and other vendors provide.

The fourth step is to run a pilot. Many of the best case studies in elevators, cranes, and automation started as single‑line or single‑car pilots with power analyzers installed. That allows you to validate energy savings, thermal benefits, and operational behavior before rolling regeneration out broadly.

Finally, feed real data back into your standards. When you have measured savings and operational experience, you can set clear criteria for when regenerative drives are required, recommended, or unnecessary in your own design guidelines.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is regenerative drive capability always worth the extra cost?

No. Regenerative capability shines in processes where braking energy is large and frequent. If your application involves mostly steady motoring with rare stops, the recoverable energy is small and a simple braking resistor is usually the better investment. Danfoss and Siemens both stress that energy recovery functions make sense where braking is a significant part of the duty cycle. The right approach is to evaluate each application based on duty cycle, load, and runtime before specifying regeneration.

Can I retrofit regeneration into an existing drive system?

Often, yes. KEB’s R6 regeneration unit is explicitly designed to connect to the DC bus of existing VFDs, replacing external braking resistors and returning energy to the supply. Elevator manufacturers offer regenerative modernization packages that add regenerative drives while reusing existing hoistway structures. In many conveyor and crane systems, it is feasible to replace drives with regenerative models during scheduled upgrades. The main constraints are the available space, the existing power distribution, and the control architecture.

Will regenerative drives create issues with my utility or generator?

They can, if not engineered properly, but modern regenerative drives are designed to be good grid citizens. ABB, Mitsubishi, and others emphasize that their regenerative drives return clean power with controlled harmonics and good power factor. In facilities with sensitive equipment or generators, you should involve your electrical engineer and drive vendor early. In some cases, you may still need a backup braking resistor for rare conditions where exporting power is not acceptable. With proper design, most plants integrate regenerative drives without trouble.

Can regenerative drives handle all my braking needs?

They can handle a large share of routine deceleration, but they are not a replacement for mechanical brakes and safety systems. Automotive studies and regenerative elevator research both underline that regeneration alone is insufficient for emergency stops and low‑speed holding. Mechanical brakes remain essential for safety and code compliance. Regenerative capability should be viewed as an efficiency function, not as the primary safety mechanism.

Closing Perspective

After years of commissioning drives in cranes, elevators, conveyors, and test rigs, I have seen too many resistor banks glowing in rooftop enclosures and hoistways, dumping perfectly good energy into the air. Regenerative drive capability is a mature way to stop that waste. When you apply it where the duty cycle justifies the investment, and you design the electrical and control side correctly, it delivers quieter panels, cooler rooms, lower bills, and better stories for your sustainability reports. The real work is not in proving that regeneration works; it is in choosing the right battles and engineering each one with the same rigor you apply to safety and uptime.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regenerative_braking

- https://ene.org/blogjuly2024/

- https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6754468/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347430145_Energy_recovery_strategy_for_regenerative_braking_system_of_intelligent_four-wheel_independent_drive_electric_vehicles

- https://www.combustion-engines.eu/pdf-207152-128197?filename=Energy%20efficiency%20of%20a.pdf

- https://www.accelerazero.com/news/what-do-regenerative-energy-100-battery-state-charge

- https://www.alphamotorinc.com/about/regenerative-braking-a-key-advantage-of-evs

- https://ameronics.com/regenerative-drives-the-future-of-efficient-motor-control/

- https://www.automotive-technology.com/articles/regenerative-braking-systems

- https://www.cupraofficial.ie/electric-and-hybrid/what-is-regenerative-braking

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment