-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Reliability Assessment of Remanufactured Industrial Components

Senior ICS Engineer, Cross-Platform Integration Specialist

Daniel Chen is a Senior ICS Engineer specializing in cross-platform I/O integration and legacy system lifecycle management. Leveraging deep technical expertise across major brands like Siemens, Bently Nevada, and ICS Triplex, he helps industrial facilities achieve maximum uptime through reliable component sourcing and strategic maintenance decisions.

When you are the one who signs off on a critical production line, “remanufactured” is not a marketing word. It is a reliability claim. The line either runs or it does not, and the difference between a well‑engineered reman component and a lightly repaired one is the difference between scheduled maintenance and a three‑day outage that burns through overtime, expedited shipping, and customer trust.

Across automotive, heavy equipment, and industrial machinery, remanufacturing has matured into a disciplined, standards‑driven practice. Studies in the remanufacturing literature show that, when it is done properly, remanufacturing can reduce production cost by roughly half and cut energy use and pollution drastically compared with building new components, while restoring quality to a level equivalent to new. At the same time, the reliability profile of a reman unit is not automatically the same as a new one, because a reman product always blends old and new hardware.

This is why reliability assessment is not optional. It is the core engineering task that turns an attractive price quote into a part you can install in a critical drive, gear train, or hydraulic circuit without losing sleep.

In this article I will walk through how to think about the reliability of remanufactured industrial components, which assessments actually make a difference in the field, and what I look for as a systems integrator before I agree to design these products into automation and control projects.

Why Reliability Assessment Is Different For Reman

Reliability figures for new products are usually based on populations built entirely from new components. Life tests, field failure data, and warranty statistics all describe that “all‑new” configuration. Refurbished or remanufactured products, by definition, contain a mix of new parts and previously used parts that have been cleaned, inspected, and either kept in service or upgraded.

Discussions among reliability engineers highlight the obvious but important consequence: unless every failure‑relevant component is replaced, the remaining aged parts will usually cap how reliable the reman product can be. Even a deep refurbishment only moves the ratio toward more new parts, it does not magically erase wear on components that stay in service.

The impact is highly product‑specific. In a DC motor, for example, if the rotor and stator are rewound and all wear components such as brushes, commutator, and bearings are replaced, reliability can reasonably approach that of a new motor. If the same motor goes back into service with original bearings, the failure risk from those bearings dominates the system, and overall reliability drops accordingly. That logic applies just as well to ball screws, servo gearboxes, hydraulic pumps, and drive electronics.

There is one important nuance. When the only reused elements are structural parts that have never shown up in your failure data, it can be defensible to claim reliability comparable to new units. Some industrial standards, such as the IEC framework for “qualified‑as‑good‑as‑new” components, explicitly recognize this idea and allow new products to contain such parts when they pass defined reliability, functionality, and usage checks.

The practical take‑away is simple. For remanufactured components you cannot rely on a generic “like new” claim. You need to understand which parts stay, which are replaced or upgraded, and how that configuration behaves under your real operating conditions.

Remanufactured, Refurbished, Rebuilt: Getting The Terms Straight

Before you can assess reliability, you need to be clear about what process you are buying.

Remanufacturing, in the strict sense used by many industrial and heavy‑equipment suppliers, is a controlled industrial process that restores used units to a like‑new, same‑as‑new, or even better‑than‑new condition. A reman process typically involves complete disassembly, thorough cleaning, detailed inspection of every component, replacement or reconditioning of worn and outdated parts, careful reassembly, and full performance testing against original specifications. Remanufactured parts are intended to match new parts in performance and often carry similar warranty terms.

Refurbished items, by contrast, are usually products where the failed or obviously worn components are replaced, some basic cleaning is carried out, and functionality is verified, but there is no systematic teardown or part‑by‑part renewal. Rebuilt products go one step further toward the minimal end: the focus is on restoring basic function by selectively repairing or replacing the broken parts, with limited testing and many original components left as they are. Rebuilt units are often the lowest cost option and may come with limited or no warranty.

These distinctions matter because they define how much of the component’s failure history you are resetting. Remanufacturing essentially re‑zeros the wear state of all critical parts, while refurbishment and rebuilding only address the subset that failed obviously this time. From a reliability standpoint, that difference is enormous.

A concise way to visualize the contrast is to look at how each approach treats process discipline, quality level, and typical warranty.

| Approach | Typical process scope | Expected quality level | Typical warranty stance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rebuilt | Selective repair of failed parts, basic testing | Functional, but below original spec | Limited or none |

| Reconditioned | Cleaning plus minor repairs and partial testing | Better than rebuilt, not to full spec | Short term, limited coverage |

| Remanufactured | Full teardown, renewal or upgrade, rigorous testing | Equivalent to or better than new | Similar to new in many applications |

When suppliers blur these definitions in their marketing, reliability assessment is the way you cut through the language and understand what you are actually getting.

What A High‑Reliability Remanufacturing Process Looks Like

In practice, the most reliable remanufactured components come from organizations that treat remanufacturing as true production, not repair. Across automotive, heavy‑equipment, and industrial machinery, several consistent themes show up in the processes used by high‑end remanufacturers.

Incoming Condition Assessment And Remanufacturability

The reliability story starts before a single bolt is loosened. Organizations that take a circular‑economy view put serious effort into condition assessment of incoming cores. Applied research groups have shown that the profitability and technical success of remanufacturing depend heavily on core quality, and they advocate a structured roadmap:

First, gather information. Usage data such as how long and under what load the product was used, design data such as the bill of materials and known failure modes, and historical data such as common repairs and spare‑parts consumption all feed into a picture of what you are likely to find inside a returned unit.

Second, run initial tests on representative products to learn which criteria really matter for value assessment. For some components, the year of manufacture and hours in service may be highly predictive; for others, software revisions or specific thermal cycles matter more. The goal is not cosmetic inspection; it is to identify the data that have predictive power for technical, economic, and environmental feasibility.

Third, execute condition assessment efficiently. Often, simple data such as year of construction and a clear photo of current state already support a first go or no‑go decision, sometimes even before the unit arrives physically. Additional inspections and tests are reserved for cases where the incremental information will actually influence the decision.

In parallel, more analytical work on remanufacturability uses decision trees and indicator models. One published method, for example, evaluates failure degree, technical feasibility, economic expectation, and environmental feasibility sequentially. If a part fails on any of these screens, it is diverted toward recycling or new replacement instead of remanufacturing. That sort of structured screening prevents you from investing time in components that cannot be restored to a reliable, profitable state.

Disassembly, Cleaning, And Dimensional Control

Once a component is accepted into the reman process, the work begins to look like precision manufacturing rather than repair.

In the heavy‑equipment world, best practice is to photograph and tag assemblies as they are disassembled, clean them thoroughly to remove contamination, then inspect every part. Housing and gear sets may undergo magnetic particle inspection or dye penetrant testing to reveal cracks that visual inspection would miss. Shafts are checked for straightness. Bearing bores are measured for out‑of‑round conditions. Gear teeth are inspected for pitting and spalling. Coordinate measuring machines are used to verify complex geometries down to thousandths of an inch.

Parts that fall outside the permissible tolerance window are either machined back into specification or replaced. The same logic applies in more compact industrial components. In remanufactured engines, transmissions, pumps, and servo actuators, components that cannot be brought back into spec are culled systematically, not left to subjective judgment on the bench.

From a reliability perspective, this is where you reset wear‑out mechanisms. The deeper and more data‑driven the inspection, the more confidently you can say that the reman unit’s failure behavior will resemble that of a new unit rather than a used one.

Replacement, Upgrade, And Delta Methodology

The next building block is how replacements and upgrades are chosen.

Some of the strongest practices come from organizations that use a new original‑equipment unit as the technical reference for the entire reman process. One European automotive remanufacturer describes a “delta methodology” in which the new OE part is characterized in detail, and every used core is compared against that reference. The difference, or delta, between the core and the OE reference defines exactly which process steps, replacements, and adjustments are needed to bring the reman part back into line.

Component sourcing is controlled with similar rigor. When possible, the original suppliers are used for replacement parts. When that is not feasible, alternative components are subjected to material analysis, hardness testing, and other validation procedures before being approved. The focus remains on eliminating any gap between the reman part and the OE reference, not on simply making the part “work again.”

In many remanufacturing operations, obsolete designs are upgraded in the process. Previous design improvements and field fixes are deliberately incorporated into reman parts to increase value and ensure compatibility with current systems. Models for in‑service machine tool remanufacturing go further, integrating condition monitoring and fuzzy evaluation of component importance and failure influence to allocate reliability targets and redesign effort where they matter most.

Testing Strategy From Subcomponent To End‑Of‑Line

The most visible reliability lever is testing. High‑reliability remanufacturers treat testing as a universal, non‑negotiable step rather than a sampling activity.

Automotive and industrial reman facilities that set the benchmark test one hundred percent of their remanufactured units, and many test critical subsystems individually before final assembly. In some engine and transmission lines, reman units are subjected to four or five times as many test points as competing products. Test plans may range from short functional checks lasting only seconds to multi‑hour endurance cycles with thousands of measurement points.

For rotating equipment, dynamometers measure torque, horsepower, and speed under load. Transmissions are tested for shift quality, gear engagement, and hydraulic pressures to clutch packs and bands. Final drives and differentials are checked for gear tooth contact patterns and backlash settings in thousandths of an inch. Hydraulic pumps are run across cold start, warm operation, and repeated cycles while technicians monitor flow rates, pressure capability, internal leakage, cavitation, and pressure spikes.

In modern electro‑hydraulic and electronic components, test benches simulate vehicle or machine environments. Electronic control units, battery management systems, and motor controllers are exercised with realistic bus traffic, sensor inputs, and fault conditions. Software calibration and firmware integrity are checked alongside electrical performance.

Mechanical testing in the laboratory plays a supporting role. Hardness testing, tensile tests, impact tests, fatigue tests, and residual stress analysis are used to validate material properties and machining quality. When applied intelligently, these tests reveal whether a remachined shaft, housing, or bracket still provides the necessary strength and toughness for long‑term service.

The common thread is simple. Testing is not just about making the part move; it is about validating structural integrity, confirming that performance meets or exceeds specification, uncovering hidden defects, and creating a documented baseline for future maintenance and warranty support.

Documentation, Standards, And Traceability

Reliability assessment is only as strong as the traceability behind it. Leading remanufacturers maintain test sheets for every component, documenting what was tested, when, by whom, and with what results. Parts are serialized, and core‑to‑record tracking supports later failure analysis if a unit returns from the field.

Many of the stronger players align their quality systems with standards such as ISO 9001 and automotive schemes like IATF 16949. Environmental management standards such as ISO 14001 are common as well, reflecting the circular‑economy role of remanufacturing. In some sectors, concepts like “qualified‑as‑good‑as‑new” components are formalized in standards that define how reliability and functionality must be demonstrated before reman parts can be reintegrated into new products.

Repairable parts management programs in large plants complement this by closing the loop on the user side. In these programs, parts are not only remanufactured; they are tracked through failure analysis, root‑cause investigation, and documentation back to maintenance and operations teams. Data from reman test reports and in‑service behavior feed into better operating practices and more targeted preventive maintenance.

Taken together, process discipline, comprehensive testing, and documentation turn remanufacturing into a repeatable, auditable reliability practice rather than a gamble.

Methods And Tools You Can Use To Assess Reliability

If you are responsible for automation and control reliability, you usually are not running the remanufacturing line yourself. Your job is to assess what comes across your desk from suppliers and decide whether it is fit for purpose. Several practical methods from industry and research can help.

Condition Assessment And Failure Data

Start with how your suppliers and internal teams define the scope of remanufacturing based on actual failure data. Reliability engineers in industrial forums emphasize building refurbishment standards around evidence: identify which components are structural and rarely fail, and which components are wear‑driven and show up repeatedly in field failures.

In a motor drive, for example, bus capacitors, power semiconductors, and cooling fans might be scheduled for replacement every time, while mechanical housings and heatsinks are reused after inspection. In a hydraulic pump, wear plates, bearings, and seals may always be replaced, while the housing is reused only after passing non‑destructive testing. If a supplier cannot clearly explain this logic, they are not managing reliability; they are performing repairs.

On your side, condition assessment starts before parts fail. Projects in the circular‑economy space show the value of collecting design data, operating data, and maintenance history to support decisions on whether a component is a good candidate for remanufacturing at all. When you know how long and how hard a component has been run, plus how it typically fails, you can set realistic expectations for the reman version.

Delta Methodology And OE References

The delta methodology used by some automotive remanufacturers is attractive for industrial users because it is transparent. When a supplier uses a new OE unit as reference and systematically defines the gap between that reference and each core, they can show you exactly what has been done to close that gap.

In practice, this can mean providing you with process sheets that indicate which subassemblies were replaced, which tolerances were restored, and which upgrades were applied when a component was brought up to current specification. It also shows up in component sourcing. If a replacement valve, bearing, or gear does not come from the original supplier, the supplier should be able to show you the validation testing that proves the alternate is equivalent.

When you see that level of discipline, the reliability assessment shifts from “Is this safe to use at all?” to “How does its risk profile compare to new, given our application?” That is a much better conversation.

Non‑Destructive And Mechanical Testing

Non‑destructive testing and mechanical testing are your friends when you need hard data instead of promises.

For castings, gears, and structural parts, non‑destructive methods such as magnetic particle inspection and dye penetrant testing pick up surface and near‑surface cracks. Ultrasonic or other volumetric methods can be added where needed. Dimensional inspection using calibrated micrometers, bore gauges, and coordinate measuring machines verifies that remachined parts truly meet the tolerances they claim.

Mechanical testing validates that the material properties are where they need to be. Hardness tests confirm that surface treatments and heat treatments are intact after reman work. Tensile and impact tests on representative samples confirm strength and toughness where it is critical. Fatigue tests and residual stress analysis are essential when machining or welding steps could have introduced stresses that shorten life.

For electrical and electronic components, reliability assessment leans more on functional testing, diagnostics, and sometimes accelerated stress testing. Endurance tests subject reman coils, windings, and control boards to repeated thermal and electrical cycling. Advanced test setups simulate field load profiles for power electronics, drives, and motion controllers.

The key is that the supplier’s testing regime must go beyond basic power‑on functionality to cover the failure modes that matter in your application.

Reliability Allocation And System Integration

Reliability allocation methods from research on remanufactured machine tools provide a helpful mindset for system integrators. In that work, remanufacturing is treated as part of a broader product–service system, and reliability targets are allocated to subsystems based on their importance and failure influence, using fuzzy evaluation methods and field data.

Translated into our world, when you integrate reman components into a complex machine or line, you do not treat every part equally. Drives and control modules that can stop an entire production cell deserve more stringent reliability requirements and closer supplier scrutiny than a reman gear reducer in a non‑critical conveyor leg. When you apply this thinking, you concentrate your assessment and qualification effort where failures hurt you most.

Evaluating Suppliers And Parts Without A Bullet Checklist

When you evaluate a reman supplier, you can usually learn more from their answers to a handful of direct questions than from pages of sales material.

Ask what tests they perform on every remanufactured unit. Serious rebuilders will talk comfortably about load tests, flow tests, pressure checks, and endurance cycles, and they will be able to show you anonymized test reports for real components. If the answer is vague or limited to basic functionality checks, reliability will track that lack of rigor.

Ask how their test equipment is calibrated and what standards they follow. If they can point to internal procedures aligned with recognized quality frameworks and show you calibration certificates for dynamometers, test stands, and measurement tools, you are dealing with an engineering‑led operation.

Ask about documentation. The better shops maintain test sheets, tie them to serial numbers, and keep records long enough to support root‑cause investigations and warranty decisions. If all you get is a handwritten tag and a verbal “it passed,” that is a red flag.

Ask about warranties and what happens when a reman part fails early. Reputable suppliers cover workmanship, explain how they separate wear from defects, and welcome failure analysis because it improves their process. Shops that offer no warranty or only nominal coverage, especially when combined with very low pricing and limited documentation, are effectively telling you that they do not expect to see the part again and are not planning to support you if it does fail.

It can help to summarize what you hear in a simple mental table.

| Signal from supplier | What it usually indicates for reliability |

|---|---|

| Clear description of full teardown, inspection, and testing | Process built for repeatable quality and predictable behavior |

| Access to sample test reports and calibration records | Data to support reliability claims and audits |

| Recognized quality and environmental certifications | Systems in place beyond individual technicians |

| Strong workmanship warranty and structured failure analysis | Willingness to stand behind reliability claims |

| No documentation, vague tests, very low pricing, no warranty | High risk of early failure and limited recourse |

For critical automation and control hardware, I treat that table as a filter. If a supplier lands in the bottom row, I do not put their components into a safety‑critical or high‑consequence application.

System‑Level Reliability With Reman Components

One of the more interesting developments in the circular‑economy literature is the concept of reintegration. Instead of using remanufactured components only as replacements in older equipment, reman parts can be reintegrated into the production of new machines, sometimes even in new generations of a product family.

Standards for “qualified‑as‑good‑as‑new” components describe how to check reliability, functionality, and usage so that such reman parts can be treated as raw material in new production. The conditions are strict. Components must undergo a regular reman process, pass defined reliability assessments, and fit within the design margins of the new product. Yet when this is done properly, it demonstrates that remanufactured components can carry system‑level reliability responsibilities, not just act as stopgaps.

In integration projects, I look at reman parts through that system lens. A reman drive or actuator does not sit in isolation; it interacts with other equipment, control logic, and safety systems. If a reman part is being used in a new system rather than as a like‑for‑like replacement, I want to see the same engineering rigor around interfaces, environmental conditions, and failure behavior that I would expect for a new design.

That can mean requesting combined tests with the reman component installed in a representative system setup, monitoring vibration, temperature, and performance across realistic load profiles. It often means augmenting the initial deployment with additional condition monitoring and conservative maintenance intervals, then relaxing those measures as field data accumulate.

In short, you integrate reman components into your reliability block diagram and hazard analysis like any other critical element, and you demand data at the same level of seriousness.

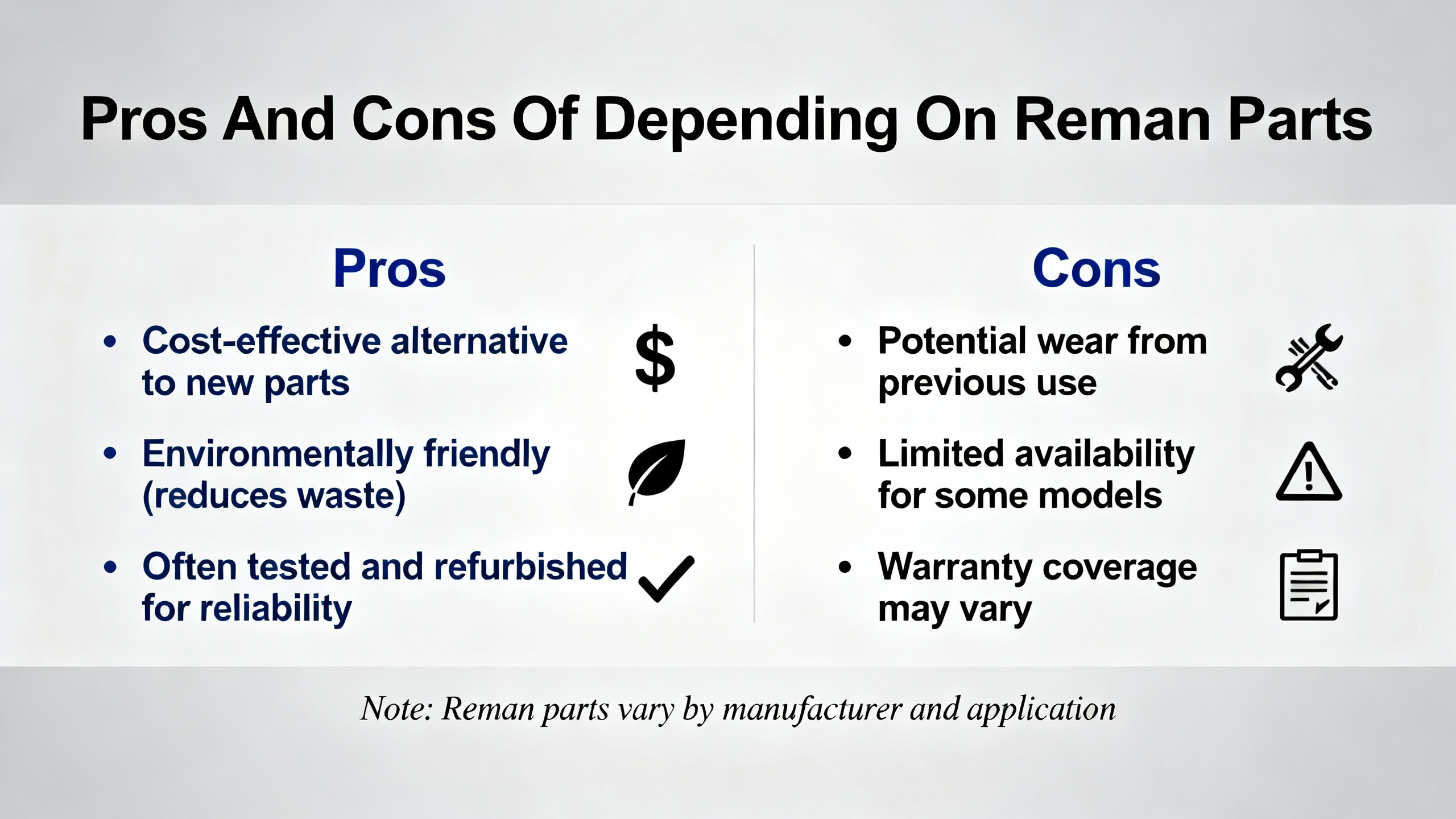

Pros And Cons Of Depending On Reman Parts

When the reman program is mature and the supplier is strong, the benefits are substantial. Heavy‑duty parts providers report cost savings on the order of forty to sixty percent compared with new components. Other sources cite reman products priced roughly twenty to forty percent below new equivalents. At the same time, remanufacturing can reduce raw material use dramatically, cut energy consumption to a fraction of that required for new production, and avoid significant amounts of waste and emissions. For fleets and plants facing budget pressure and sustainability targets, that combination is powerful.

Remanufactured components also help with availability. In some cases, a reman unit can be turned around faster than a new part can be obtained, especially when supply chains are tight. When your spare‑parts strategy includes a structured repairable parts program, you can reduce overall parts spending significantly and shift maintenance from reactive repairs toward more planned interventions.

The drawbacks arise when reman is treated as “cheap repair” rather than engineered production. Core quality varies. Some suppliers cut corners on inspection, testing, or component replacement. Others lack the documentation and standards discipline needed to sustain quality over time. For highly safety‑critical or regulatory‑constrained systems, not every reman route will pass muster.

There is also the fundamental fact that reman components blend new and old materials. If wear‑critical parts are not fully renewed, or if field environments are harsher than what the reman process assumed, reliability can suffer. That is why explicit standards based on failure data and condition assessment are so important. They turn reman from a guess into a controlled engineering decision.

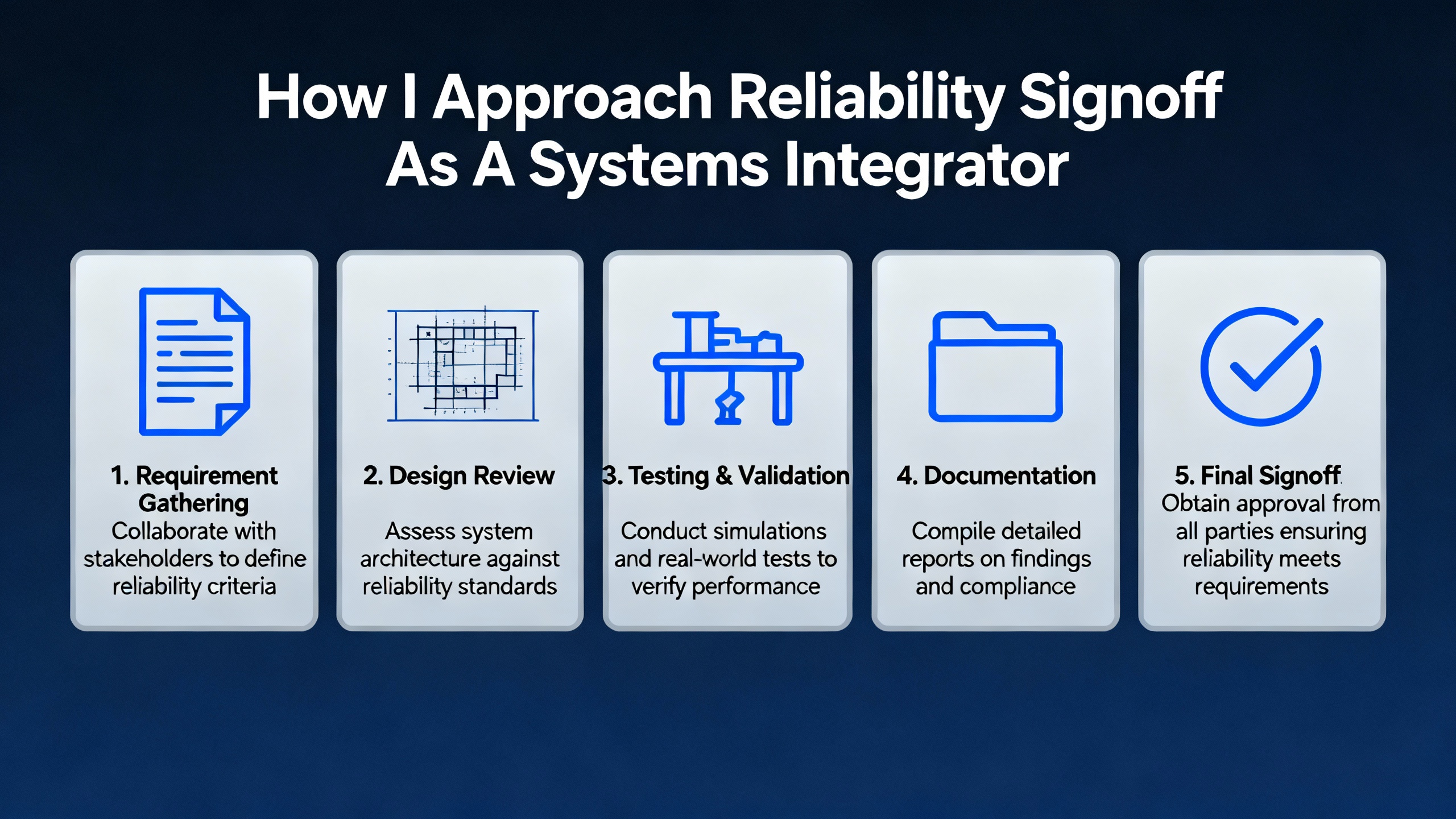

How I Approach Reliability Signoff As A Systems Integrator

When I am responsible for signing off on a project that uses remanufactured components, I take a layered approach.

First, I classify where reman parts will sit in the system and what the consequence of their failure will be. A reman servo in a non‑critical handling application is one thing; a reman hydraulic pump in a press that can stop an entire plant is another. This classification drives how demanding I am on data and testing.

Second, I filter suppliers using the process and documentation signals described earlier. I look for evidence of full teardown, controlled component replacement, systematic testing, and traceable records. Certifications and standards alignment are not sufficient on their own, but they are good corroborating evidence.

Third, I request specific technical information. That includes the list of components that are always replaced, the list that are conditionally reused, summaries of test protocols and pass criteria, and sample test reports. For higher‑risk applications, I insist on seeing load and endurance test results that are relevant to our duty cycles.

Fourth, I treat the initial deployment as a learning phase. Where practical, I instrument the system to capture temperature, vibration, and cycle counts on reman components and set conservative maintenance triggers. This is particularly important when using reman components in upgraded systems or new product generations, where reintegration concepts from standards are being applied in the real world.

Finally, I feed the results back into our own standards. When reman components from a given supplier demonstrate consistent reliability in service, I document that and expand their use where appropriate. When early failures or data gaps appear, I either tighten application constraints or move to alternative sources.

Over time, this approach builds a portfolio of reman options that I trust, a clear view of where they make sense, and a track record that maintenance and operations teams can rely on.

Common Questions On Reliability Of Remanufactured Components

Can Remanufactured Components Be As Reliable As New?

Yes, they can, under the right conditions. When remanufacturing replaces every wear‑critical component, restores dimensional and material properties within specification, and verifies performance via comprehensive testing, field reliability can approach that of new units. This is especially true when structural parts that remain in service have no history of failures. Standards that define “qualified‑as‑good‑as‑new” components are built on exactly this logic. The key question is whether the specific reman process for your component meets those conditions.

How Long Will A Remanufactured Component Last In Service?

There is no single answer, because life depends on design, operating conditions, and how thoroughly the reman process resets wear mechanisms. Industry articles on rebuilt components warn that inadequate testing can make the difference between a component that lasts on the order of one hundred hours and one that runs for ten thousand hours. In other words, if reman is treated as superficial repair, life can be very short. When reman is executed as full renewal with realistic load and endurance testing, life expectancy can be comparable to new, and in some upgrade cases even better.

Is It Safe To Use Reman Parts In Safety‑Critical Applications?

It can be, but only when the same rigor is applied as for new components. Safety‑critical parts such as brake systems, steering assemblies, and fuel modules in vehicles are remanufactured and tested to strict standards including burst pressure tests, leak detection, and response‑time measurements, and they operate under regulatory frameworks equivalent to new production. In industrial automation, the same principle applies. You must ensure that the reman supplier’s process and test coverage meet the safety requirements of your application and that documentation is sufficient to support audits and incident investigations.

Closing Thoughts

Remanufacturing is no longer a side show in industrial maintenance. Done properly, it is a disciplined way to recover value, cut cost and carbon, and keep legacy equipment running without sacrificing performance. From a systems integrator’s perspective, the question is not whether remanufactured components can be reliable; the question is whether a specific reman process for a specific product has earned that trust.

If you treat reliability assessment of reman components with the same seriousness you apply to new designs, insist on data instead of slogans, and partner with suppliers who welcome that scrutiny, remanufacturing can become a dependable part of your automation and control strategy rather than a source of surprises.

References

- https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1876418

- http://www.apics.org/docs/default-source/industry-content/apics_reverseman_report_full_version.pdf

- https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1999814/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344425192_Reliability_Allocation_Method_for_Remanufactured_Machine_Tools_Based_on_Fuzzy_Evaluation_Importance_and_Failure_Influence

- https://borgautomotive-reman.com/how-can-you-tell-if-a-remanufactured-product-is-good-quality/

- https://constructionequip.com/rebuilt-components-testing-standards/

- https://www.fleetconceptsinc.com/remanufacturing-and-its-importance-to-the-heavy-duty-parts-industry/

- https://www.gregorypoole.com/guide-to-remanufactured-parts/

- https://www.recoequip.com/blog/best-practices-for-remanufactured-parts-tips--22950

- https://www.advancedtech.com/blog/4-keys-successful-repairable-parts-management-program-blog/

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment