-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

How to Select a Redundant Controller for Critical Infrastructure Protection

Critical infrastructure operators do not buy redundant controllers because they are fashionable. They buy them because a single missed switchover can mean fuel not moving through a pipeline, water not being treated correctly, or a substation going dark at the worst possible moment.

From work in power, water, chemicals, and large manufacturing, I have learned that selecting a redundant controller is less about a spec sheet and more about how that controller behaves in the ugliest one percent of scenarios. That is exactly where critical infrastructure protection lives.

This article walks through how to think about redundant controllers for high‑consequence environments, using practical lessons echoed by organizations such as CISA, NIST, Rockwell Automation, ISA, and others. The goal is to help you choose a design that genuinely protects your infrastructure, not just adds a second PLC and a false sense of security.

What Critical Infrastructure Protection Really Demands

Critical infrastructure protection covers the assets and systems whose failure would have a debilitating impact on national security, the economy, or public health and safety. Federal guidance from agencies such as CISA and DHS notes that this includes sectors like energy, water and wastewater, transportation systems, communications, emergency services, financial services, and more. Policy documents summarized by Zentera emphasize that modern protection is no longer just fences and cameras; it is an integrated program that spans cyber, physical, operational, and supply chain risks.

CISA’s material on critical infrastructure security and resilience frames protection as a risk‑management exercise, not a checklist. It highlights that most infrastructure is privately owned in the United States and that operators must identify and prioritize their essential functions, understand how those functions can fail, and then apply layered security and resilience measures. Redundancy, network diversification, incident response planning, and good cybersecurity hygiene are described as core resilience practices.

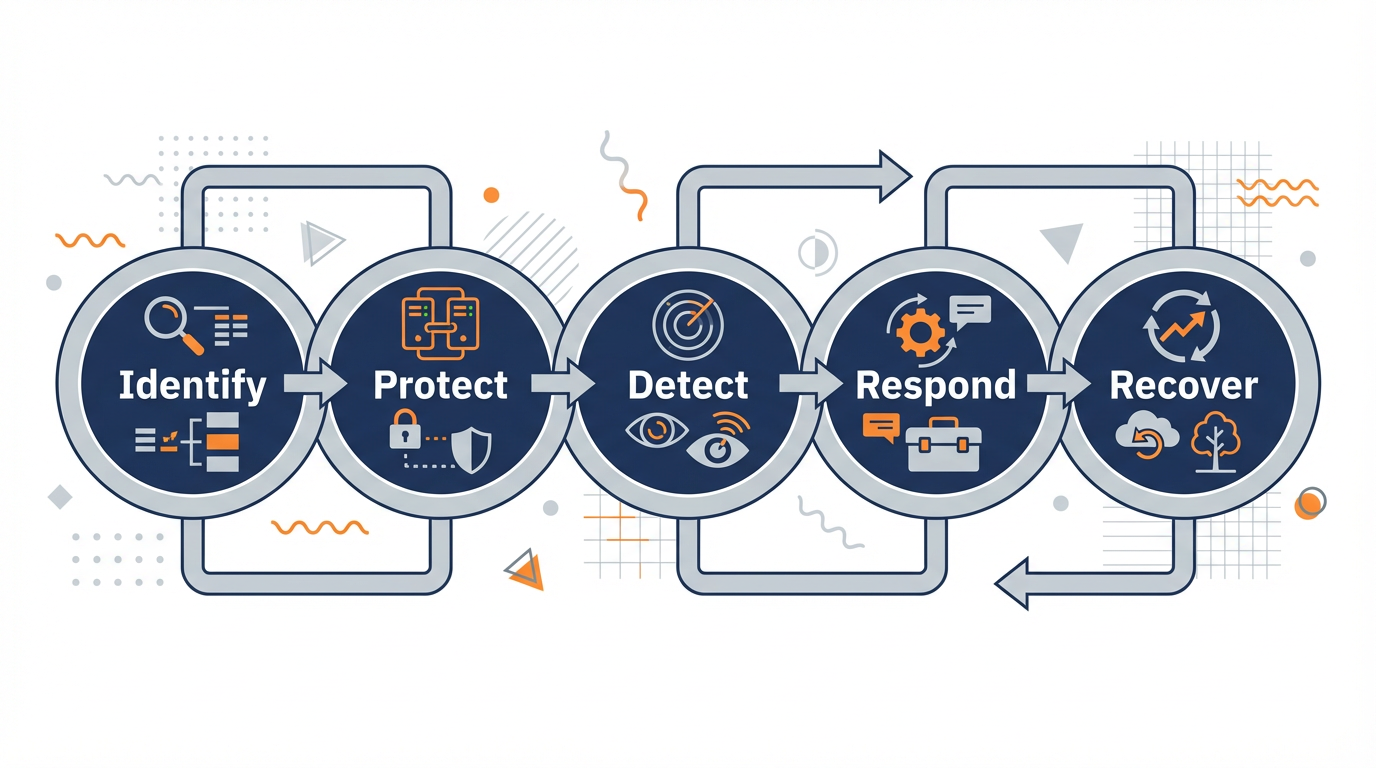

NIST’s Cybersecurity Framework reinforces the same idea. It organizes cybersecurity activities into five functions—Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover—and into categories and subcategories that can be mapped to standards and controls. The framework describes a seven‑step process where organizations prioritize and scope, understand their systems and context, build a current profile, assess risk, define a target profile, analyze gaps, and implement an improvement action plan. For control systems, redundant controllers are one of the tools you use inside that broader program, not the starting point.

In other words, a redundant controller is valuable only to the extent that it supports a risk‑based, resilience‑focused design. If you select redundancy without that context, you risk spending money without materially improving critical infrastructure protection.

Redundancy, Reliability, and Resilience: Getting the Terms Straight

Many projects get into trouble because teams mix up basic concepts. JD Solomon’s work on redundancy for facilities and critical infrastructure is useful here. Reliability is defined as the probability that an item will perform its intended function for a specified interval under stated conditions. Redundancy is the existence of more than one means for accomplishing a given function, and those means do not need to be identical. A redundant controller pair is one means; a controller plus a manual fallback procedure can also be a form of redundancy.

Systems can pursue two complementary paths to prevent failure. Fault avoidance tries to make individual components more reliable through better materials, higher‑quality parts, and de‑rating. Fault tolerance accepts that components will still fail and adds redundancy, fault detection, and automatic switching so that a fault does not become a service failure.

The Splunk discussion of redundancy versus resiliency adds another important distinction. Redundancy is about deliberate duplication of components or paths so backups can take over. Resiliency is about the system’s ability to absorb disruptions, adapt, and recover quickly. You can build redundant controllers and still have a brittle system if you ignore incident response, recovery procedures, and people.

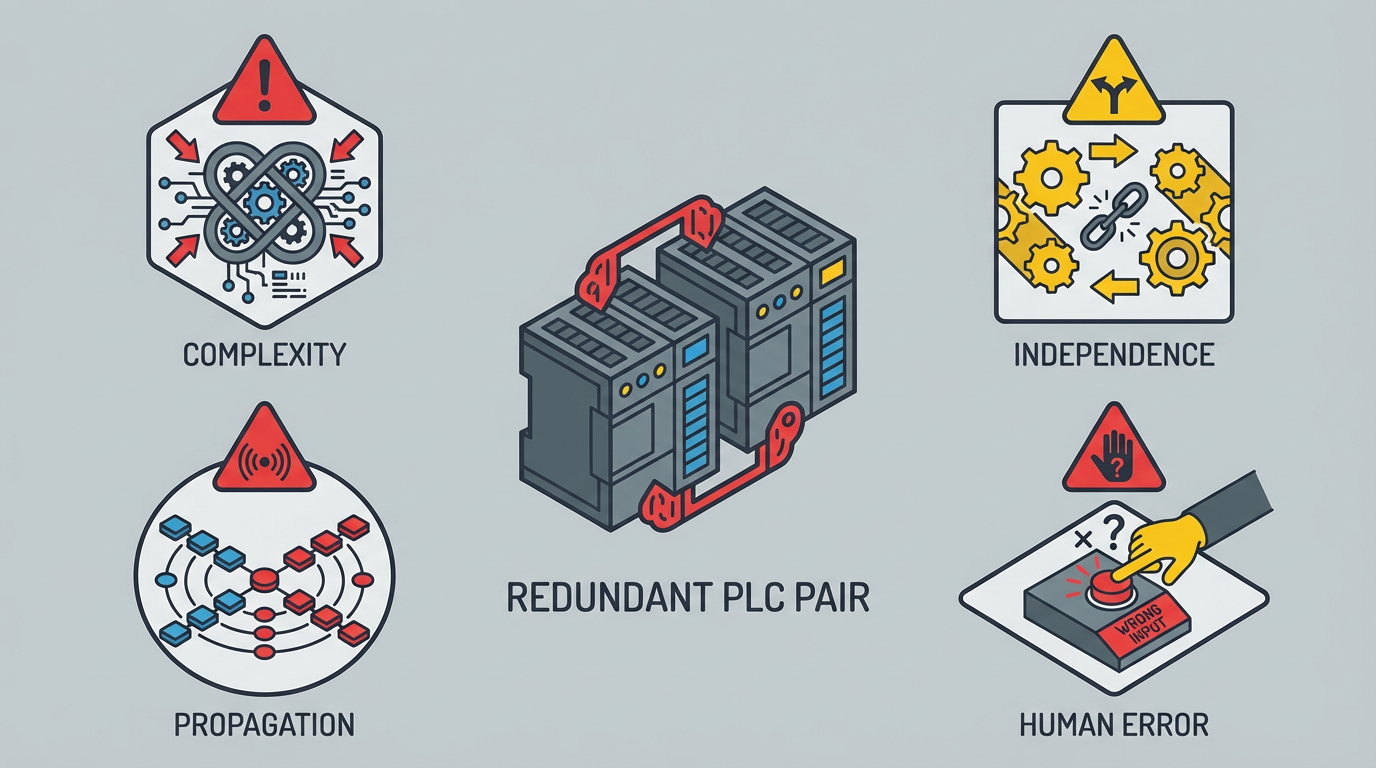

JD Solomon also warns about what he calls the four horsemen of redundancy: complexity, independence, propagation, and human error. Adding redundant controllers increases complexity, because now you must understand and manage more equipment and interactions. Independence is often assumed but not achieved; two controllers on the same power feed can fail together. Propagation describes how upstream failures, such as power or environmental issues, can defeat local redundancy. Human error is ever‑present, because people design, configure, maintain, and operate these systems, and many fault‑tolerant schemes depend on operators to recognize failures and respond correctly.

Those four horsemen show up over and over again in real control rooms.

Any selection process for a redundant controller that does not account for them is incomplete.

Controller Redundancy Architectures in Practice

Industrial controller redundancy is a high‑availability strategy that removes the PLC as a single point of failure so critical automation can continue running despite faults in controllers, power, or networks. ISA’s discussion of controller redundancy and related coverage on Automation.com outline the architectures you see in real plants.

A typical design uses a pair of controllers configured as primary and secondary. Rockwell Automation’s ControlLogix redundancy, for example, uses two identical controllers, such as units from the 1756‑L7x or 1756‑L8x families, set up as primary and backup. Each controller sits in its own chassis with its own power supply and network modules. A redundant media module such as the 1756‑RM2 provides high‑speed synchronization between chassis so that the secondary continuously mirrors the primary’s program and state. Field I/O is reached over networks like ControlNet or EtherNet/IP.

The same pattern appears with other vendors. ISA’s article describes redundant PLC processors sharing field I/O networks arranged in rings so both processors can reach all devices. The primary executes the logic, while the secondary stays in lockstep and is ready to take over immediately when the primary fails.

PC‑based and SCADA systems follow similar ideas. Control Engineering describes “mirroring backup” systems where a second computer continuously collects the same data as the primary and can take over control without disturbing the process. SCADA and distributed control systems use redundant servers so that if one server fails, HMIs and view nodes automatically route to the backup.

Underneath these variations sit three fundamental redundancy modes.

Hot, Warm, and Cold Standby

ISA and Automation.com describe three common modes you will encounter when you evaluate redundant controller offers. The differences matter a lot more than marketing brochures suggest.

| Mode | Description | Typical use and behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Hot standby | Secondary controller is powered, fully synchronized, and ready at all times | High‑availability systems needing failover within a scan or milliseconds, effectively bumpless for the process and the HMI |

| Warm standby | Secondary is installed and often powered but not fully synchronized | Applications that can tolerate manual intervention and seconds or minutes of downtime when switching over |

| Cold standby | Spare controller is on the shelf or in the rack but not in service | Cost‑sensitive plants relying on technicians to replace hardware during an outage |

Hot standby redundancy is what most critical infrastructure operators think they are buying. In this mode, the primary controls I/O and continuously updates the secondary with I/O status, memory, and program changes. If the primary suffers a major fault such as a power failure, cut cable, rack fault, or processor error, the system performs a switchover, also called failover, and the secondary takes over seamlessly.

Warm standby can be acceptable where loss of a line or machine for a short period is tolerable. Cold standby is not a high‑availability solution at all; it is simply good sparing practice.

When you select a redundant controller, one of the first questions should be which mode it actually implements in your use case and what failover times the vendor is willing to specify and support.

Synchronization Quality and Switchover Determinism

Not all redundancy implementations are equal under the hood. Automation.com highlights synchronization quality as a critical differentiator. Best‑in‑class systems perform full memory and I/O synchronization every scan and execute primary and secondary logic in lockstep. They exchange this data over a dedicated synchronization network, often a fiber link that can stretch to roughly 6 miles, so you can place controllers far apart for physical diversity.

Other platforms try to optimize for normal performance by synchronizing by exception or by sharing the I/O and sync traffic on the same network. That approach can produce unpredictable failover behavior, reduce usable memory, and lead to cascade failures when large amounts of data change at once. ISA notes that some PLCs even restrict usable memory, sometimes up to half, just to keep synchronization working.

Switchover determinism is another key criterion. ISA recommends that redundant solutions guarantee a maximum failover time and deliver seamless behavior so the process and supervisory systems do not see unacceptable disturbances. In fast processes, such as power management and distribution, plants may require failover within milliseconds. In slower batch operations, a slightly longer transient might be acceptable.

Lastly, pay attention to how the redundancy design impacts HMIs and SCADA. Some implementations suffer from “HMI blind time” during failover, where supervisory systems cannot read or write controller tags. Others keep HMI communications continuous because the secondary controller inherits the primary’s data set and communication sessions. For operators in a control room, that difference is the edge between annoyance and a serious safety concern.

When You Actually Need Redundant Controllers

It is tempting to say that if one controller is good, two must be better. ISA and Automation.com point out that redundancy used to be reserved for the most crucial applications because implementations were complex and expensive. Modern platforms have improved the price‑performance ratio, but that does not mean every pump station deserves a dual‑controller architecture.

Vertech’s guidance on redundant PLCs is blunt about this. PLC hardware failures are relatively rare compared with failures in other parts of the system. Depending on how much downtime actually costs, a pre‑programmed spare PLC on the shelf or an in‑rack spare that can be enabled by a programmer may be a more practical and cost‑effective choice than full online redundancy.

JD Solomon warns of a common mistake: assuming redundancy exists and will work without testing and validation. Another is deferring preventive maintenance because equipment is “redundant.” If the standby controller or power supply has quietly failed or fallen out of sync, you only discover it when you need it most. That lesson applies equally to redundant controllers, pumps, and power systems.

From a critical infrastructure protection standpoint, CISA and Zentera emphasize risk‑based decisions. Sites that provide electricity, water, wastewater treatment, fuels, or emergency communications are not all equal. Some facilities are primary sources; others provide backup capacity or serve smaller populations. NIST’s Cybersecurity Framework encourages operators to prioritize based on critical functions and consequences. For some assets, redundancy at the controller level is mandatory; for others, investments might be better placed in improved monitoring, incident response, or upstream power redundancy.

The right question is not whether redundancy is theoretically good. The right question is whether a hot‑standby controller pair meaningfully reduces risk for a given function at an acceptable total lifecycle cost.

Selection Criteria for Redundant Controllers in Critical Infrastructure

Once you have justified that you really need redundant controllers, the next step is to choose the right platform and architecture. The following criteria synthesize guidance from ISA, Automation.com, Rockwell Automation, Vertech, Hallam‑ICS, CISA, NIST, JD Solomon, and others.

Start with a Risk‑Based Design, Not a Part Number

NIST’s Cybersecurity Framework and DHS guidance for AI in critical infrastructure both emphasize an organized process. You start by prioritizing and scoping the systems you care about, then you understand your systems, assets, and regulatory context, then you characterize your current posture, assess risk, define a target posture, analyze gaps, and implement improvements.

Applied to redundant controllers, that means identifying which functions in your plant are truly critical to safety, environment, and continuity of service. It means understanding what happens if a controller output freezes, if it repeats a stale command, or if it briefly loses communication with I/O. It also means considering cyber risk; DHS’s AI and safety guidelines highlight the need to inventory technology that influences critical functions, secure it by design, and plan for both misuse and malfunction.

Only after that work should you talk about specific PLC families or redundant media modules.

Otherwise you are buying hardware without a clear view of how it supports your critical infrastructure protection obligations.

Demand Deterministic, Tested Failover

ISA and Automation.com both insist that deterministic switchover is an essential requirement. The vendor must be able to specify a maximum failover time and make sure the controller pair behaves predictably at that limit. Rockwell Automation’s documentation for ControlLogix redundancy describes commissioning practices where engineers explicitly simulate primary controller failures and use Studio 5000 diagnostics to verify seamless, automatic switchover with no process interruption. That mindset should be standard in critical infrastructure projects regardless of platform.

The selection process should include questions such as how the controller handles a processor fault, a backplane fault, a power outage on one chassis, and a network partition. You should understand whether the secondary can be forced to assume control for planned maintenance and whether that transition behaves the same way as a fault‑driven failover.

Testing is not a one‑time activity. Rockwell Automation and Automation.com both recommend regularly scheduled redundancy tests and continuous monitoring of redundancy health and synchronization status. CISA’s resilience guidance similarly encourages regular exercises and continuous monitoring as part of a national risk‑management approach. If your operational procedures and staffing model do not support those practices, a sophisticated redundant controller platform will not deliver its potential.

Inspect Synchronization and Physical Architecture

Synchronization is where many redundant controller designs either shine or fail. ISA’s analysis of controller redundancy explains that optimal implementations fully synchronize all data and I/O memory every scan and execute logic in lockstep. Automation.com adds that this should occur over a dedicated sync network so the I/O network remains available and deterministic.

Rockwell Automation’s ControlLogix design with 1756‑RM2 redundant media modules between chassis is a concrete example. Each controller chassis has its own power supply and communication modules. The redundant media module links the two chassis, sharing the controller program and state in real time so the secondary mirrors the primary.

When you evaluate options, you should look for:

Deterministic full‑scan synchronization rather than best‑effort, by‑exception sync that can struggle under heavy changes.

Dedicated synchronization links rather than shared paths that compete with I/O or HMI traffic.

Independent controller chassis and power supplies so a rack or power failure cannot take down both controllers at once.

ISA also highlights the value of geographic diversity. Locating each member of a redundant pair in separate rooms or buildings reduces the chance that a localized fire, flood, or other physical incident disables both. Automation.com notes that dedicated fiber sync links can support distances of roughly 6 miles, which is enough in many plants to separate controllers meaningfully.

Engineer Network and I/O Redundancy Around the Controller

A redundant controller on a fragile control network is like a lifeboat with a hole in the bottom. Hallam‑ICS outlines best practices for redundant industrial control networks that pair well with controller redundancy.

On topology, common options are ring, star, and mesh. A ring topology connects devices in a loop so that if a single link fails, traffic can flow the opposite direction. It generally offers fast recovery and is often the most cost‑effective redundant topology. A star topology connects devices to a central switch; a link failure affects only the connected device. Redundant star designs duplicate links and use redundant core and edge switches for higher resilience where budgets allow. A mesh topology provides multiple redundant paths between devices and delivers high fault tolerance at the cost of complexity and hardware expense, so it is usually reserved for the most critical systems.

Key components also need redundancy. Hallam‑ICS recommends multiple switches to eliminate single points of failure, redundant links using aggregation techniques such as Ethernet link aggregation, and redundant power supplies or uninterruptible power supplies for critical network equipment. Spanning Tree Protocol must be configured carefully; Rapid Spanning Tree Protocol or Multiple Spanning Tree Protocol usually provide faster convergence and better load balancing than default STP.

Network segmentation is equally important. Hallam‑ICS advises separating traffic into different VLANs for control, SCADA, database, and management, which improves performance, security, and the ability to prioritize critical control traffic. ISA points out that fieldbuses such as PROFINET are often implemented as redundant rings and should be natively supported by the PLC or edge platform to avoid gateways as extra failure points.

On the supervisory side, OPC UA is highlighted by ISA as a preferred protocol from redundant PLCs to higher‑level systems because it includes redundancy mechanisms in its specification, supports rich industrial data models, and provides encryption and authentication. Control Engineering notes that SCADA and DCS platforms often use redundant servers so HMIs can automatically reroute to a backup.

For critical infrastructure, this all connects directly to CIP guidance. Zentera and CISA both stress network segmentation, least‑privilege access, and continuous monitoring as core cybersecurity practices. Racoman’s discussion of remote monitoring for sewage systems emphasizes segregating monitoring from control so that an attack on one component does not immediately compromise the other. A controller‑level redundancy plan that ignores these network and I/O dimensions is incomplete.

Plan for Long‑Term Maintenance, Cybersecurity, and Upgrades

Redundant controller platforms run for decades in environments where both equipment and threat landscapes change. ISA and Automation.com emphasize that modern PLCs are highly networked and must receive periodic firmware updates to address cybersecurity issues and add features. A redundant system that cannot be upgraded without a shutdown is not truly redundant in practice.

ISA notes that many implementations today require exact matches of hardware, firmware, and software versions across the pair, sometimes even to the point that a mismatch can trigger a shutdown. More flexible platforms tolerate mixed versions during a controlled upgrade window and let you upgrade components without bringing the process down, as long as synchronization lists and configuration remain compatible.

DHS’s AI safety and security guidelines for critical infrastructure reinforce this outlook. They call for secure‑by‑design and secure‑by‑default systems, continuous monitoring, and the ability to fall back to manual or non‑AI modes during incidents. Even if you do not use AI in your control loop, those principles apply directly: your redundant controller design should allow fallbacks, upgrades under load, and robust logging and monitoring.

Rockwell Automation recommends ongoing monitoring of redundancy health and synchronization status using built‑in diagnostics, along with regular, planned redundancy tests. JD Solomon warns that one of the most common mistakes is assuming redundancy will work without exercising the fault detection and switching mechanisms. For critical infrastructure, scheduled failover drills and documented recovery procedures are not optional extras; they are part of the protection strategy.

Balance Complexity, People, and Procedures

JD Solomon’s four horsemen of redundancy are especially relevant for controller selection.

Complexity grows with redundancy. Each additional controller, network, I/O path, and power feed is another place where configuration errors and latent faults can hide. Vertech notes that implementing redundant PLCs requires more than buying a second CPU; you need separate racks, power supplies, and communication cards, which significantly increases hardware cost and design complexity. The more intricate the solution, the more disciplined your engineering and change management must be.

Independence is easily overestimated. Redundant PLCs on the same UPS or breaker do not provide true independence; a common failure in power can take them both out. Vertech points out that power failures and breaker trips are more common than PLC hardware failures, so each rack should have an independent power source or be tied into a genuinely redundant UPS scheme. Similar considerations apply to cooling, networking, and enclosure environmental protection.

Propagation describes how failures in upstream or adjacent systems can cascade into downstream systems despite local redundancy. JD Solomon’s examples from aviation illustrate how unexpected interactions can defeat redundancy. In the industrial world, a fire in a cable tray, unexpected heat from adjacent equipment, or a flood in a control room can render two carefully engineered controllers useless simultaneously. Physical layout and environmental protections matter as much as logic design.

Human error remains a critical factor. Vertech stresses that redundant PLC systems are more complex to maintain and that maintenance staff must be trained and regularly practiced in recovery procedures. JD Solomon cautions that many redundant schemes depend on people to recognize a fault and correctly switch to standby, and that the reliability of this human switching often governs the overall system reliability. Splunk’s discussion of resilience underscores that resilient systems depend as much on people and processes as on equipment.

If your team is thinly staffed, or if procedures are not routinely exercised, that reality should influence how much redundancy you pursue and how you design it.

Think End‑to‑End Redundancy: Monitoring, Remote Access, and Cloud

Critical infrastructure protection does not stop at the controller cabinet. CISA, DHS, and Zentera all emphasize end‑to‑end resilience that considers monitoring, remote access, and cloud services.

Emergency24’s description of alarm monitoring redundancy provides a useful analogy. The company operates geographically diverse monitoring stations so that if one site is disrupted by a disaster or outage, others can continue operations. All stations are certified to independent safety and performance standards, with backup power and multiple communication paths. The architecture automatically reroutes monitoring tasks from a failing station to another operational station without manual intervention.

Racoman’s work on sewage infrastructure monitoring advocates for segregated and redundant monitoring systems. A minimum recommended level of redundancy is an independent monitoring system that continues to track infrastructure and alert operators even if the primary monitoring or control system is disabled or hacked. The article points to real incidents, such as the Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack and the Oldsmar, Florida water treatment cyber attack, as examples of why separated monitoring, robust alerting, and strong cybersecurity controls matter.

Control Engineering reminds us that redundancy extends into servers, storage, and networks. PC‑based control systems often rely on redundant disks with RAID or mirroring, redundant network paths, and redundant SCADA servers that HMIs can automatically fail over to.

Data center practice, summarized by Socomec, offers additional patterns. Power architectures use models such as N+1, 2N, 2N+1, and more advanced configurations like 3N2 or Catcher designs to balance cost, efficiency, and fault tolerance. The key takeaway is that redundancy is applied thoughtfully, with clear decisions about which loads require full duplication and which can accept N+1 protection. The same thinking should guide which parts of an industrial control system get hot standby, which get sparing, and which rely on robust but simplex designs.

Zentera notes that national policy is moving toward resilience‑focused design that assumes compromise and emphasizes redundancy and fail‑safe operation. That philosophy should be reflected in how you connect redundant controllers to remote access solutions, cloud historians, and enterprise integration.

A Practical Selection Workflow

Turning all of this into a decision on an actual project, a pragmatic approach usually looks like this.

You begin with a structured risk assessment using concepts from NIST’s Cybersecurity Framework and CISA’s resilience guidance. That means identifying your critical functions, understanding how they support national or regional priorities, and mapping how control systems implement them. You then rate the consequences of controller failure or misoperation for each function.

For functions where controller failure directly threatens safety, environmental compliance, or essential service delivery, you determine whether true hot‑standby redundancy is required. You clarify acceptable failover times and process behavior during switchover. That might mean, for example, that a power distribution control system must fail over within milliseconds and maintain continuous telemetry to SCADA, while a backup water treatment train might tolerate a slightly slower switchover.

You then shortlist controller platforms that natively support redundancy, not ones that require extensive custom programming to approximate it. Vertech advises confirming that the specific manufacturer and model support redundancy properly, because some products only offer partial redundancy or rely on user‑written failover logic.

For each candidate platform, you evaluate the architecture: independent racks and power, dedicated synchronization links, supported redundancy modes, deterministic failover guarantees, impact on usable memory, and version‑tolerant upgrade procedures. You examine how the platform integrates with redundant I/O networks, VLAN segmentation, OPC UA, and supervisory redundancy.

The next step is to design and review the broader redundancy scheme. You decide where to use ring, redundant star, or mesh network topologies as Hallam‑ICS describes. You specify redundant switches, links, and power for network infrastructure. You define VLANs for control, SCADA, database, and management traffic. You integrate redundant servers, historian, and alarm systems where necessary, and you define how remote access and cloud services will behave during failover.

Finally, you bake testing and maintenance into the plan. You define how often you will test controller failover, how you will verify synchronization health, and how firmware upgrades will be conducted without downtime. You align those practices with DHS’s recommendations for continuous monitoring and incident response for critical infrastructure systems. You train your operations team and document procedures, recognizing that human performance is part of the redundancy design.

If you follow that sort of workflow, the choice of redundant controller becomes a logical outcome of your risk and architecture decisions rather than a one‑off purchase.

Short FAQ

Do I always need redundant PLCs for critical infrastructure?

Not always. Vertech points out that PLC hardware failures are relatively rare and that a pre‑programmed spare on the shelf can sometimes be a better use of budget, especially where downtime costs are moderate and recovery can be performed safely. For functions whose failure could cause major safety incidents, environmental harm, or extended outages in sectors like energy or water, hot‑standby redundancy is often justified, but the decision should follow a risk assessment rather than habit.

If I buy a redundant controller, am I automatically resilient?

No. Splunk’s analysis of redundancy versus resiliency makes it clear that duplication alone does not guarantee resilience. JD Solomon’s four horsemen—complexity, independence, propagation, and human error—show how poorly managed redundancy can even reduce reliability. CISA and NIST both emphasize that resilience requires governance, monitoring, incident response, and continuous improvement. A redundant controller is one piece of that puzzle, not the whole picture.

How should I think about cloud and remote monitoring in a redundant design?

Emergency24 and Racoman’s examples show that redundant, geographically diverse monitoring and segregated architectures greatly improve resilience. When you integrate cloud historians, analytics platforms, or remote access tools, design them with the same principles: no single monitoring node or network path should be able to fail silently, and an attacker should have to compromise multiple independent systems to blind you. That often means independent monitoring channels, redundant servers, strong network segmentation, and disciplined security controls.

Closing Thoughts

Redundant controllers can be powerful tools for protecting critical infrastructure, but only when they are selected and engineered as part of a disciplined, risk‑based architecture. If you treat them as a line item to check a box, you risk paying for extra hardware without actually improving resilience.

When I come into a project as a systems integrator and long‑term partner, I am less interested in how many controllers are on the proposal and more interested in how the whole system behaves when something important fails. If you approach redundant controller selection with that mindset—grounded in standards, informed by real‑world behavior, and honest about your team’s capabilities—you put your plant, and the communities it serves, on much stronger footing.

References

- https://www.cisa.gov/topics/critical-infrastructure-security-and-resilience

- https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/cswp/nist.cswp.04162018.pdf

- https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2024-04/24_0426_dhs_ai-ci-safety-security-guidelines-508c.pdf

- https://eiscouncil.org/redundancy-critical-infrastructure/

- https://www.isa.org/intech-home/2021/june-2021/features/under-the-hood

- https://www.zentera.net/blog/critical-infrastructure-protection

- https://www.automation.com/article/controller-redundancy-under-hood

- https://www.controleng.com/redundancy-in-control-3/

- https://www.cowangroup.co/news/redundancy-in-engineering

- https://www.emergency24.us/https-www-emergency24-us-the-importance-of-redundancy-in-alarm-monitoring/

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment