-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Just-in-Time Delivery for PLC Parts: Reducing Downtime the Right Way

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

Why PLC Parts Downtime Hurts More Than You Think

When a conveyor motor fails, you can often limp along on a parallel line. When a sensor dies, an operator can sometimes bypass a station temporarily. When a PLC CPU or I/O card fails, the entire line goes dark.

PLC hardware is the brain of your automation. As Hale Engineering points out, its condition directly affects safety, productivity, and regulatory compliance. Panelmatic notes that as PLCs age, spare parts become scarce, software support disappears, and failures become more frequent and harder to fix. Balaji Switchgears adds that legacy PLCs also suffer from a shrinking pool of engineers familiar with them.

Put simply, a missing PLC module is not the same as a missing box of bolts. If your stockroom does not have the right module on the shelf and your supplier cannot get one to you fast, you are not just inconvenienced. You are down.

At the same time, finance is pushing to reduce working capital. Articles from NetSuite, Brightpearl, and others show how much money sits on shelves in traditional inventory models and how Just-in-Time (JIT) has helped manufacturers free up cash, reduce waste, and respond faster to demand.

That is the tension this article addresses. As a systems integrator who has supported aggregate plants, food and beverage facilities, and automotive Tier 1 suppliers, I have seen both extremes: stockrooms full of obsolete PLC cards that will never be used, and lean operations that save a few thousand dollars in inventory but lose far more in avoidable downtime.

JIT delivery for PLC parts can reduce downtime and cost, but only if it is designed with the realities of controls hardware, supplier reliability, and field maintenance in mind.

What Just-in-Time Really Is (And Is Not)

Across sources like NetSuite, Do Supply, Brightpearl, Throughput, Insia, Arkestro, and C.H. Robinson, the definition is consistent. Just-in-Time is a lean management and supply chain strategy where materials arrive exactly when they are needed for production or fulfillment, with minimal on-hand inventory. It grew out of the Toyota Production System and Kaizen, and it is now common in automotive, electronics, retail, and fast food.

Do Supply emphasizes that JIT is a management philosophy, not a single trick. The idea is to produce only what customers order, in the right quantity and quality, at the right time, while eliminating waste across the supply chain. NetSuite and Brightpearl highlight the financial side: reducing storage, obsolescence, shrinkage, and freeing working capital for better uses. Brightpearl notes that holding excess inventory can add roughly one-third in annual carrying costs when you consider storage, losses, and obsolescence.

JIT also leans heavily on supplier integration and quality. Throughput and Insia both stress that accurate demand forecasting, real-time visibility, and strong supplier collaboration are foundational. Many sources refer to techniques like Kanban pull signals, smaller batch sizes, cross-docking, and continuous improvement as core JIT tools.

The big warning is also consistent. Mitsubishi Electric, NetSuite, Brightpearl, Sage, and others all show how ultra-lean JIT magnifies risk during disruptions. Mitsubishi Electric cites survey data showing that a large majority of manufacturers had to significantly reduce or shut down production during the COVID period, and that recovery often took a year or more. They describe situations where high-value products were stuck for lack of low-cost parts because inventories were too lean. NetSuite and Sage likewise warn that minimal buffers make operations vulnerable to supplier failures, transportation problems, and sudden demand spikes.

Recent supply chain commentary, including work highlighted by Supply Chain Dive, is not calling JIT obsolete. Instead, it points to a shift toward more nuanced strategies that balance JIT with what Brightpearl and Mitsubishi Electric call “Just-in-Case” safety stock for selected items.

For PLC parts, that nuance is absolutely essential.

Where JIT Fits for PLC Parts

If you think of JIT as “no inventory,” it will fail for PLC spares. Do Supply and NetSuite are clear that JIT requires stable, predictable demand and highly reliable suppliers. Insia adds that traditional higher-stock approaches may be safer in volatile or highly uncertain environments.

PLC spares sit at an awkward intersection. Demand is lumpy and often driven by failures, not steady consumption. Lead times can spike when semiconductor supply is tight. Balaji Switchgears stresses that spare parts for legacy PLCs are already scarce, which is one of the reasons modernization becomes unavoidable.

At the same time, not every PLC-related part is rare or critical. Modern, standardized platforms with active manufacturing, strong distribution, and robust logistics can support JIT-like replenishment for many items.

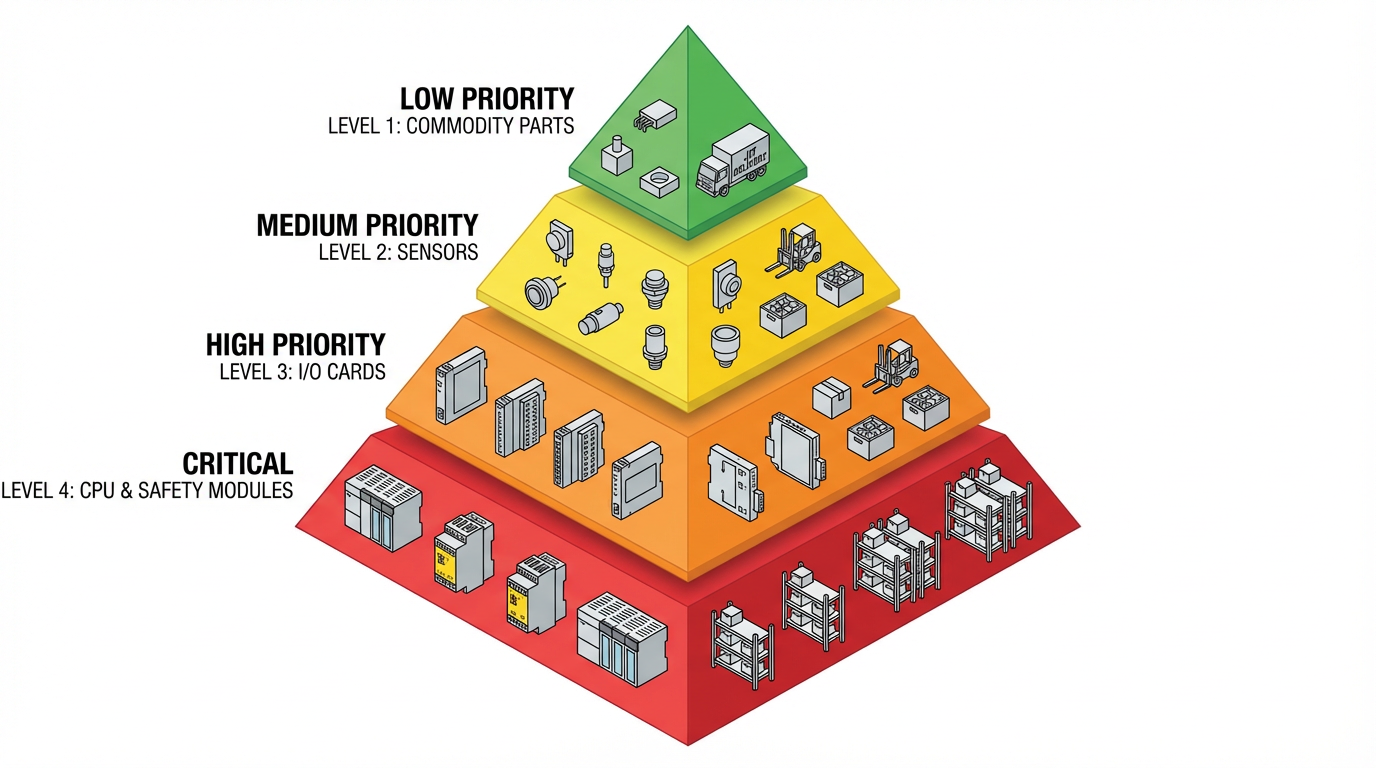

In practice, most plants do best by splitting PLC-related parts into distinct risk categories and applying different stocking and delivery strategies to each.

| Part category | JIT suitability for downtime reduction | Typical policy that tends to work in practice |

|---|---|---|

| CPUs, safety PLCs, key communication modules | Low. Failures stop major systems; lead times can stretch in crises. | Keep at least one local spare per critical system; use JIT only beyond that buffer. |

| Standard I/O cards on current platforms | Medium. Failures are serious, but demand and lead times are more predictable. | Hold a small on-site buffer; replenish via JIT based on usage and failure data. |

| Sensors, relays, power supplies | High. Widely available, failure rates easier to model, many alternates. | Rely more heavily on JIT or vendor-managed inventory with short SLAs. |

| Obsolete or end-of-life PLC components | Very low. Parts are scarce and may disappear entirely. | Build a targeted “last-time-buy” stock while planning migration off the platform. |

This table reflects patterns supported indirectly by the sources. Balaji Switchgears and Panelmatic both highlight obsolescence and scarce spares as drivers for PLC upgrades. Mitsubishi Electric emphasizes that ultra-lean inventories create bottlenecks when key components are missing. Insia and NetSuite make the point that JIT works best where demand is stable and the supply base is reliable.

The implication is straightforward. Use JIT aggressively where risk is manageable and supply is robust. Use it cautiously, with local buffers, where a single missing module can shut you down.

Benefits and Trade‑offs for PLC Spares

For PLC parts specifically, JIT-style delivery brings several real advantages if you engineer it correctly.

First, it reduces dead stock and obsolescence. Panelmatic and Balaji Switchgears both describe the problem of legacy PLCs whose hardware has reached the end of its lifecycle. Companies stuck with cabinets full of unused cards for obsolete platforms know the pain. By aligning replenishment with actual usage and failure patterns, you reduce the odds of buying parts that never get used before a migration.

Second, it improves cash flow and warehouse efficiency. NetSuite, Brightpearl, and Throughput all describe how JIT reduces capital tied up in stock, storage space, and labor spent on handling inventory. For controls, that may mean fewer shelves full of duplicate power supplies, I/O cards, and CPUs for every production line, and more standardized parts that can be shared across lines with fast replenishment.

Third, it tightens supplier performance. One Union Solutions and C.H. Robinson show how JIT programs force clarity around service level agreements, transit times, exception management, and communication. For PLC spares, that can translate into concrete commitments such as “this CPU, from this distributor, will be on your dock within a set number of hours, with real-time tracking and proactive alerts when something slips.”

However, the trade-offs are serious.

Mitsubishi Electric and Brightpearl both warn that JIT increases vulnerability to supply chain disruptions and price swings. If your JIT PLC supplier depends on a semiconductor vendor that suddenly faces long lead times, that risk comes straight to your plant floor. NetSuite and Sage underline that poor forecasting or overconfidence in a single supplier can quickly turn JIT into “just too late.”

For PLC parts, the biggest risk is not carrying cost; it is unplanned downtime. Hale Engineering shows that well-maintained PLC systems can cut downtime and improve efficiency, as demonstrated in an automotive plant where their PLC health program reduced downtime and increased efficiency in the first year. That underscores the main point: the goal is not minimum inventory; it is maximum uptime at acceptable cost.

The right JIT design for PLC parts reduces dead stock and frees capital while preserving, or improving, your ability to recover from failures quickly.

Designing a JIT Strategy Around PLC Reality

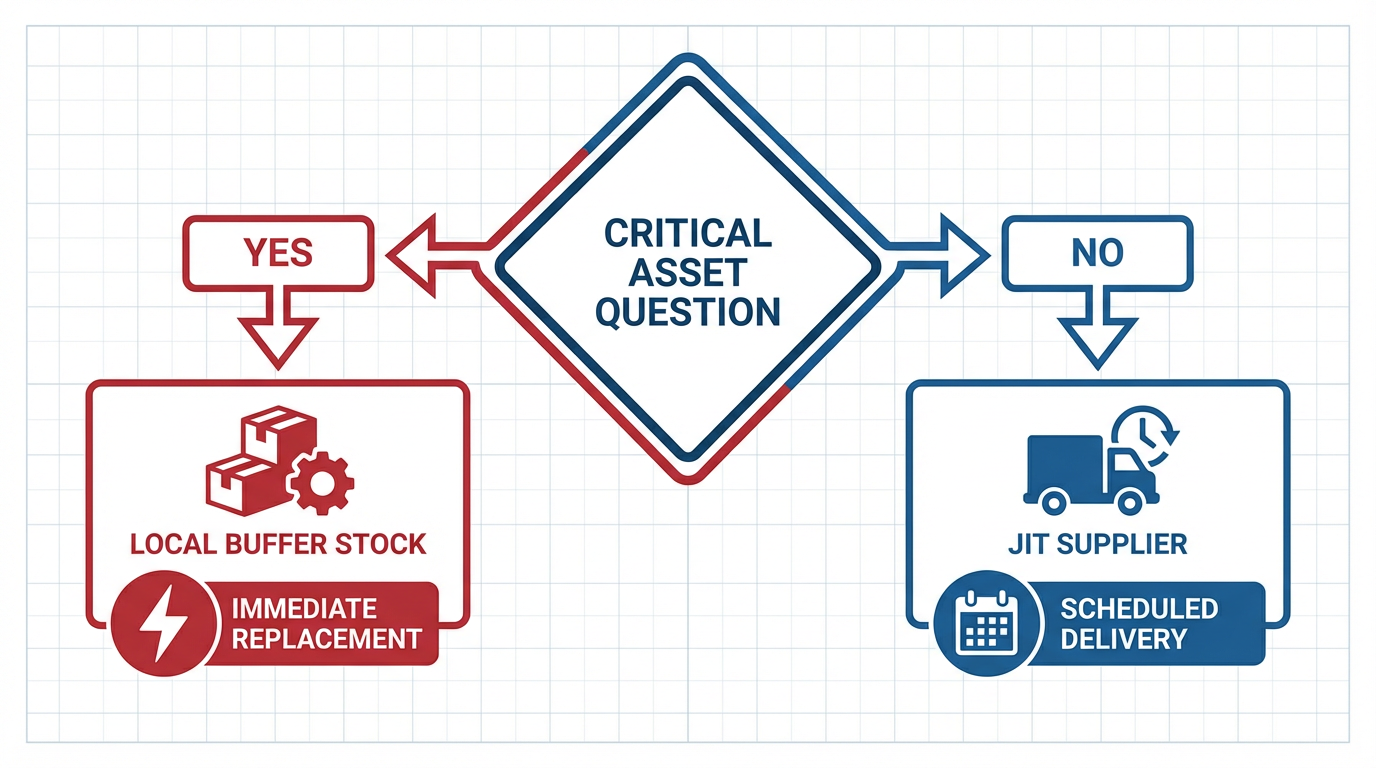

Start with Criticality and Consequence

JIT decisions for PLC parts must start from risk, not from a target inventory dollar figure.

Hale Engineering recommends treating PLC reliability as a safety and compliance issue, and their maintenance guidance centers on structured inspections, backups, and redundancy. Insia and Do Supply both stress that JIT should be implemented as a system that eliminates waste while protecting quality and service.

In practical terms, walk your plant and ask a simple question for each PLC-controlled system. If this CPU, rack power supply, or safety PLC dies at 3:00 AM, how long can we afford to be down, and what is the cost per hour?

For truly critical assets, design your stock and JIT strategy so that you can replace failed modules within that tolerance regardless of what your carrier or distributor is dealing with that night.

For less critical assets, you can lean more heavily on JIT and supplier SLAs.

Use Maintenance and Diagnostics Data to Drive Replenishment

Modern PLC systems, as described by Pacific Blue Engineering, Houston Electric, Hale Engineering, and Schneider Electric, collect rich data: cycle counts, currents, temperatures, error logs, and event histories. Predictive maintenance strategies based on these signals have already been shown to cut unplanned downtime by identifying issues before they fail.

You can tap the same data streams to drive JIT-like replenishment for PLC parts.

For example, when PLC-based diagnostics indicate that certain I/O modules or power supplies are approaching their design limits based on run hours, load, or error patterns, you can automatically trigger purchase orders or vendor notifications so replacement units arrive just before you reasonably expect to need them.

Insia highlights the role of real-time data, analytics, and platforms that track key metrics like lead times, stockouts, and supplier on-time delivery. Throughput and NetSuite both emphasize that JIT thrives on precise, current information. Tying your PLC diagnostics, maintenance management system, and procurement system together is how you get JIT benefits without guessing.

Build Supplier and Logistics Capability Before You Cut Stock

JIT is not a stockroom project; it is a supply chain project.

C.H. Robinson’s automotive JIT guide outlines what reliable just-in-time logistics looks like: a coordinated supply chain, real-time tracking, firm SLAs, multimodal options, and proactive exception management. They describe automotive programs running with four-hour delivery commitments and cross-border lanes running on forty-eight-hour agreements, enabled by technology that offers highly accurate estimated arrival times and item-level visibility.

One Union Solutions and Arkestro echo the same themes for auto parts: evaluate end-to-end flows, choose dependable suppliers whose locations and transportation networks support JIT, enforce clear SLAs, and use technology for visibility and analytics.

For PLC parts, that suggests a checklist. You need distributors who can commit to realistic, tested delivery times for your region. You need shared visibility into order status, including backorders and substitutions. You need clear escalation paths when flights are canceled, roads close, or customs delays appear. And you need integration between your ERP or CMMS and their systems, whether through EDI, APIs, or simpler mechanisms, so that replenishment signals do not get lost in spreadsheets.

Brightpearl and NetSuite both recommend robust inventory management software and tight supplier portals for effective JIT. Without that backbone, cutting spares inventory first and “figuring out supply later” is simply gambling with uptime.

Balance JIT with Just‑in‑Case Buffers

Nearly every JIT source in the research touches on the need for balance now. Mitsubishi Electric highlights a shift where many manufacturers plan to increase inventory levels for resilience. Supply Chain Dive reports that companies are moving away from pure JIT toward more flexible models. Brightpearl’s discussion of Just-in-Case inventory notes that for some items higher stocks are justified to avoid stockouts.

For PLC parts, a balanced model might look like this in practice. You maintain a small, local “risk buffer” of truly critical modules for key lines: CPUs, rack power, critical communications, and a handful of the most failure-prone I/O types. Everything beyond that is covered by JIT agreements and vendor-managed inventory.

Insia advises treating JIT as a holistic system and recommends multi-sourcing and small strategic buffers rather than true zero stock. Sage suggests using decoupling points, so upstream and downstream processes can continue when some materials are delayed. Applying the same idea to PLC spares, you can decide where a failure must be covered by local hardware and where you can rely on a fast JIT shipment without jeopardizing safety or major output.

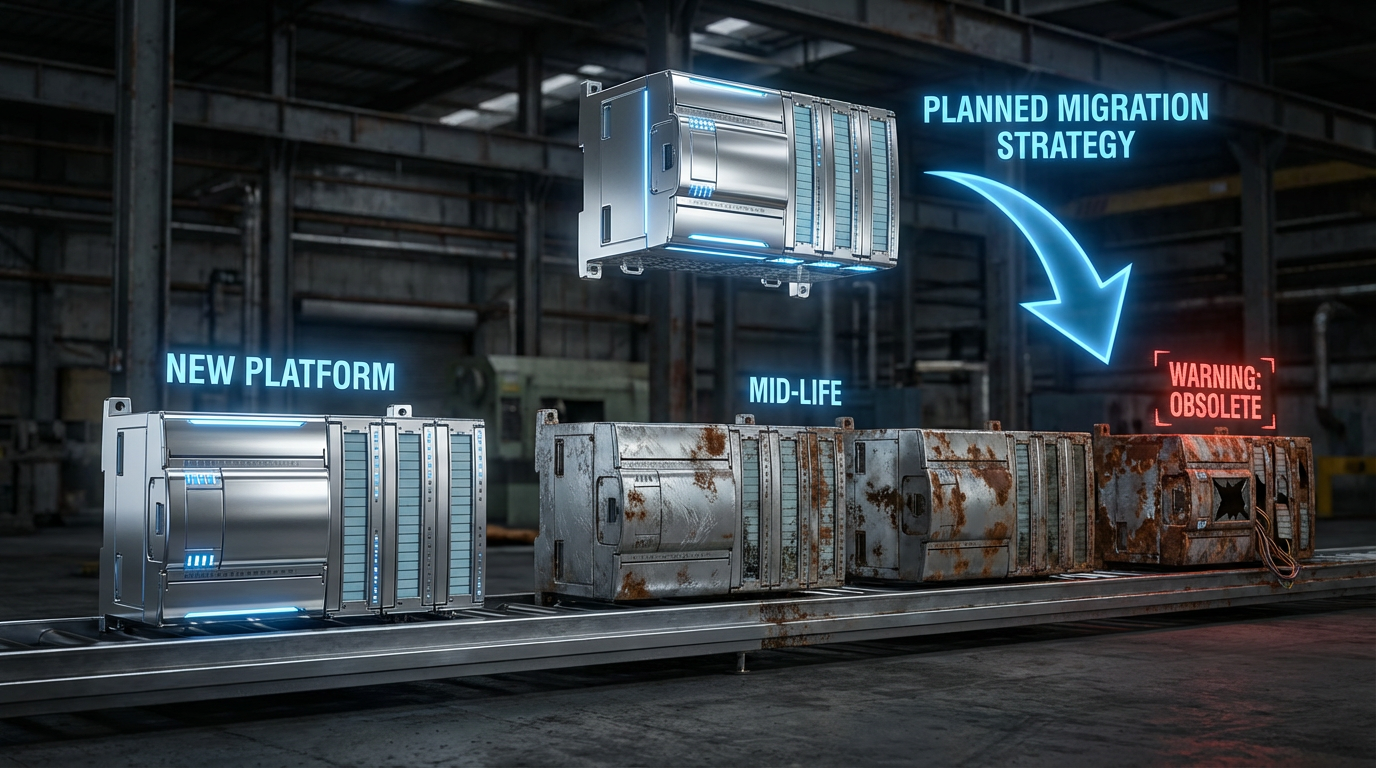

Tie JIT Spares to Your PLC Migration Roadmap

At some point, JIT for certain PLC parts becomes impossible because the parts simply do not exist. Balaji Switchgears and Panelmatic both emphasize that aging PLCs face obsolete hardware, unsupported software, cybersecurity gaps, and scarce spare parts. Schneider Electric’s modernization guidance stresses the importance of planning migrations before obsolescence becomes a crisis.

JIT can actually support a smoother transition if you integrate it with your modernization program.

For legacy platforms, you can use JIT to limit new purchases to what you truly need to bridge the gap to a replacement system, while you shift your primary spares investment to your future standard platform. Panelmatic recommends structured upgrade processes that include site evaluation, design, panel work, software development, testing, and commissioning. Balaji Switchgears describes phased migration strategies that keep production running while components are upgraded.

The key is to avoid using JIT as an excuse to delay the hard decision. When spare parts for a PLC family are routinely late, expensive, or only available via secondary markets, it is a signal to accelerate migration, not a reason to double down on risky procurement tactics.

JIT vs Traditional PLC Stocking: A Quick Comparison

A concise way to think about JIT for PLC parts is to compare it directly to the traditional “buy a lot and keep it all on the shelf” model.

| Dimension | JIT‑oriented PLC spares | Traditional PLC spares stocking |

|---|---|---|

| Working capital | Lower; parts purchased closer to time of need | Higher; more capital tied up for long periods |

| Obsolescence risk | Lower if tied to migration plans and demand signals | Higher; shelves accumulate obsolete modules over time |

| Downtime risk | Lower for non‑critical items; higher if buffers are too thin for critical hardware | Lower for critical items if coverage is well-designed; higher if “stock everything” leads to neglect of lifecycle issues |

| Complexity | Higher; depends on supplier integration and data | Lower; relies more on internal stockroom practices |

| Upgrade and standardization | Easier to pivot once contracts and systems are aligned | Harder; sunk cost in old parts can delay migration decisions |

NetSuite, Brightpearl, Insia, and Do Supply all reinforce that the financial and operational benefits of JIT show up when it is implemented as a system. The table above reflects those trade-offs when that system is applied specifically to PLC parts.

Implementation Roadmap: From Stockroom to JIT‑Enabled Spares

Moving from ad hoc ordering or static min–max levels to JIT-inspired PLC spares is not a flip of a switch. It is a series of changes that you can roll out in controlled steps.

Insia, Throughput, and C.H. Robinson all advocate beginning with a thorough assessment. That means mapping your installed PLC base, your current spares inventory, your historical failures, and your supplier performance. Panelmatic and Schneider Electric both emphasize the value of detailed site evaluations before taking on major control system projects; you should apply the same discipline to your spares strategy.

Once you understand where you are, pick a limited pilot. Sage recommends starting JIT with a controlled system rather than the entire operation. In practice, that might mean focusing on one production line or one PLC platform. Choose a mix of parts: some critical modules where you will maintain a small local buffer and rely on JIT for the rest, and some non-critical parts where you will lean heavily on JIT.

In parallel, work with your suppliers and logistics partners to harden the supply chain. C.H. Robinson and One Union Solutions outline concrete steps: align expectations and SLAs, define cut-off times, agree on exception handling processes, and implement real-time tracking. Ensure your purchasing system and your suppliers’ systems can exchange data effectively, whether through EDI, APIs, or a simpler structured process.

Then, connect your maintenance and operations data to procurement. Pacific Blue Engineering and Houston Electric highlight the value of PLC-based data for predictive maintenance. Use that to forecast the need for certain parts, and let those forecasts drive automated replenishment signals within agreed JIT windows.

Throughout the pilot, measure what matters. Insia and Throughput point to metrics like inventory turnover, lead times, stockouts, and supplier on-time performance. For PLC-specific JIT, add metrics such as mean time to repair after a PLC fault, incidents where lack of spares extended downtime, and parts written off due to obsolescence. Use those numbers to refine thresholds, buffers, and contracts.

Once the pilot is stable and the numbers show that downtime risk is controlled and inventory quality has improved, scale gradually to more lines, more parts, or more plants.

Common Failure Modes and How to Avoid Them

The JIT literature is full of cautionary tales, and many of them map directly onto PLC parts.

Brightpearl and Sage describe companies that interpreted JIT as “slash inventory across the board” without investing in forecasting, systems, and supplier relationships. In the PLC context, that looks like stripping stockrooms bare and assuming overnight shipping will always be there. Mitsubishi Electric’s analysis of COVID-era disruptions is a clear warning that this assumption does not hold in the real world.

NetSuite and Insia both highlight the risk of overreliance on a single supplier and underestimating demand variability. For PLC parts, that might be a single distributor or a single platform vendor. When they face allocation issues or lifecycle changes, your JIT program should not be the first time you discover that.

Do Supply and Sage warn against treating JIT as a purchasing project instead of an operations and engineering project. Successful implementations involve production, maintenance, quality, and finance. For PLC spares, maintenance teams and controls engineers understand criticality and failure patterns; if they are not deeply involved in JIT decisions, the program will be fragile.

Finally, Panelmatic, Balaji Switchgears, and Schneider Electric all remind us that technology lifecycles matter. A JIT program that ignores the age and support status of your PLC platforms can give a false sense of security. It is possible to have beautifully automated JIT ordering for parts that will become unobtainable in the next lifecycle change.

In my experience, the plants that succeed with JIT for PLC parts behave differently. They treat PLC spares as part of an integrated reliability strategy rather than as an isolated cost line. They use data from PLCs and CMMS systems to drive decisions. They selectively build safety buffers where downtime risk is highest. And they negotiate supply arrangements and logistics paths that are tested, not merely promised.

Short FAQ

Is true “zero stock” JIT realistic for PLC spares?

For the highest-impact PLC components, almost never. Insia and NetSuite both note that JIT works best where demand is stable and supply chains are reliable. Mitsubishi Electric’s discussion of pandemic disruptions shows how quickly lean systems break under stress. For critical PLC hardware that can shut down a plant, a small on-site buffer combined with JIT replenishment is usually the practical sweet spot.

How can I justify some local PLC stock if we are “going JIT”?

The same sources that praise JIT, such as NetSuite and Brightpearl, emphasize return on investment and customer satisfaction, not inventory reduction for its own sake. The cost of a few CPUs and rack power supplies on your shelf is often trivial compared with the cost of an hour of lost production and the risk to customer commitments. Framing the discussion in terms of uptime, safety, and avoided expedited costs tends to resonate better with finance than arguing about “engineering preferences.”

What metrics should I watch to know if JIT is helping or hurting?

Insia and Throughput recommend tracking inventory turnover, stockouts, lead times, and supplier on-time delivery. For PLC parts, add downtime hours attributable to lack of spares, mean time to repair for PLC-related incidents, number of obsolescence write-offs, and accuracy of supplier lead times against SLAs. If downtime and obsolescence are going down while cash tied in inventory is shrinking or stable, your JIT design is probably working.

Closing Thoughts

A good JIT program for PLC parts does not feel dramatic. It feels boring in the best way: critical modules are always available when you need them, your shelves are not full of relics from platforms you no longer run, and your suppliers quietly hit their commitments.

As a systems integrator and project partner, my goal is to design control systems and spare-part strategies that let your teams sleep at night. When you combine disciplined PLC maintenance, a realistic approach to risk, and a carefully engineered JIT supply network, you reduce downtime and cost at the same time—without betting your plant on the next truck showing up exactly on time.

References

- https://www.houstonelectricinc.net/our-blog/how-plc-programming-services-enhance-efficiency-in-manufacturing-automation

- https://www.brightpearl.com/just-in-time-inventory-system

- https://automationelectric.com/how-plc-controls-improve-aggregate-industry-production/

- https://balajiswitchgears.com/upgrading-plc-systems-strategies-for-modernization/

- https://hale-eng.co.uk/ensuring-operational-excellence-the-vital-role-of-plc-maintenance/

- https://www.hollingsworthllc.com/how-just-in-time-delivery-affects-supply-chain-management/

- https://www.insia.ai/blog-posts/just-in-time-supply-chain-management

- https://www.lafayette-engineering.com/lei-plc-controls/

- https://pacificblueengineering.com/how-plc-programmer-boost-manufacturing-performance/

- https://www.procore.com/library/just-in-time-delivery-construction

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment