-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Liquidation Services for Surplus Automation Parts: A Veteran Integrator’s Playbook

When I walk into an older plant, I usually see the same thing tucked at the back of the MRO crib: racks of sealed PLC modules, obsolete drives, and HMIs that nobody wants to throw away and nobody has time to deal with. That "just in case" stock quietly becomes a six figure problem.

Over the last couple of decades working as a systems integrator and project partner, I have sat on both sides of this equation. I have helped production teams keep legacy lines alive with hard to find parts, and I have helped CFOs turn idle automation stock back into working capital. Liquidation services are where those two realities meet.

This article is a practical guide, grounded in what specialist firms and marketplaces are doing today, on how to use liquidation services to handle surplus automation parts without losing money, control, or sleep.

Why Surplus Automation Parts Pile Up

Surplus does not happen because people are careless. It happens because plants evolve faster than the storeroom.

Industry research on asset recovery and surplus equipment points to the same triggers again and again. When production lines are modernized, the project usually leaves behind redundant PLC racks, drives, I/O, and control panels. When OEMs such as ABB, Siemens, Schneider, Omron, or Rockwell retire product families or change platforms, maintenance teams overbuy "last time buy" spares to protect uptime. When plants close, consolidate, or relocate, pallets of automation gear are left that no longer fit the new footprint. Over years of incremental improvements, technical stores simply become overfilled.

Automa.Net, an industrial asset recovery provider that focuses on automation, describes surplus coming from redundant PLCs, robots, modules from retired power plants, and long tail MRO inventory. United Industries points out that these are usually fully functional assets created by technology upgrades, demand shifts, or project changes rather than failures.

Surplus also accumulates for softer reasons. Maintenance managers are understandably conservative about risk, especially with legacy systems. If a critical drive goes obsolete, they keep more spares than models or data would suggest. Engineering may order safety stock for a major retrofit and never true it back down. Purchasing may buy in bulk to capture price breaks without a clear plan to burn down the extra.

The result is the same: capital sitting on shelves instead of in new automation, people, or capacity.

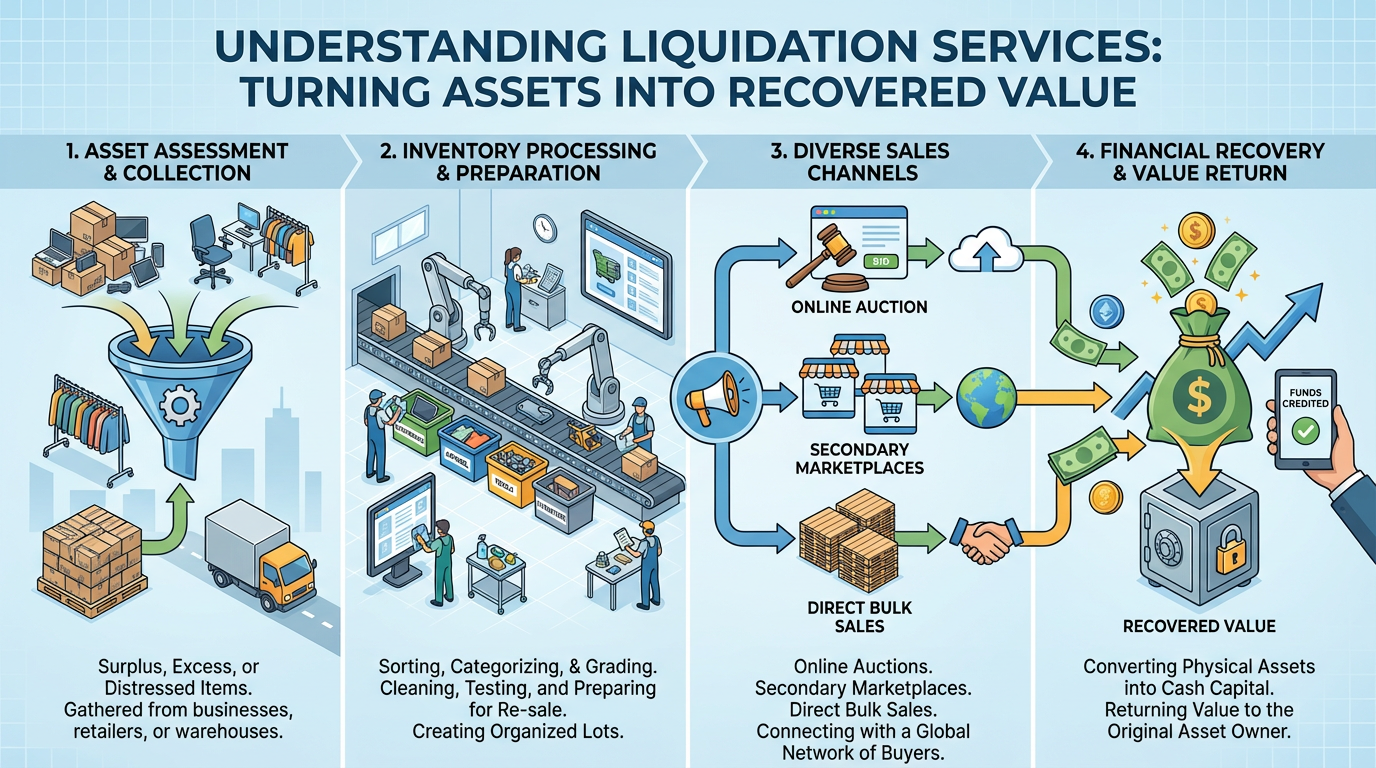

What Liquidation Services Actually Do

The term "liquidation" is often misunderstood. In a retail context, it sounds like a fire sale. In industrial automation, good liquidation services are closer to structured asset recovery.

Invrecovery defines corporate surplus asset disposition as a deliberate process: identify surplus or outdated assets, assess their value, select appropriate channels, and execute resale, reuse, or recycling for financial and environmental benefit. Automa.Net applies that logic specifically to unused or obsolete automation equipment instead of letting it be scrapped or forgotten.

It helps to separate a few concepts:

Surplus parts are items that sit above what you realistically need for uptime and maintenance. They are still saleable and useful to someone else.

Obsolete parts are components that see very little demand and may only fetch value in specialized channels or scrap. Amikong, which focuses on industrial control stock, makes this distinction clear and notes that obsolete inventory usually requires steep write downs or disposal.

Asset recovery is the overarching strategy of reclaiming value from these categories instead of carrying them indefinitely.

Liquidation services are the partners and platforms that turn that strategy into execution. They include outright surplus buyers, consignment programs, specialized marketplaces, auctions, brokers, and surplus management firms. They differ in speed, price, and how much work you keep versus outsource.

Getting clear on those definitions up front is important, because the right liquidation model depends on whether you are clearing out a closed plant, trimming MRO overstock, or cycling out a specific brand like Allen Bradley after a platform change.

The Real Cost of Sitting on Surplus Automation Parts

If you think, "Storage is cheap, we will deal with it later," you are probably underestimating the bill.

United Industries estimates that carrying costs on unused equipment can reach roughly 15 to 25 percent of the equipment value per year once you factor in storage, maintenance, climate control, and insurance. They also note that many items lose about 20 to 30 percent of market value in the first year of sitting idle. Amikong adds that maintenance and preservation alone can run around 9 to 12 percent annually for industrial control inventory, and that total holding costs, including space and administration, can reach about 20 percent per year.

United Industries reports that plants commonly sit on about 50,000 to 200,000 dollars of recoverable surplus value. At those carrying cost rates, you can easily burn the equivalent of a new robot, a small line upgrade, or a full SCADA refresh every few years just by leaving shelves untouched.

The problem is not limited to heavy equipment. Microflex points to National Retail Federation data showing that in the retail world, about 1.43 trillion dollars is tied up in inventory, and IHL Group estimates overstocks alone cause roughly 472.5 billion dollars in lost sales. While that research focuses on consumer goods, the financial mechanics are the same in industrial MRO. Money locked in dead stock cannot be invested in higher value projects.

Cash flow pain is real even for larger industrial organizations. Charcap cites Intuit surveys showing that three out of five small businesses struggle with cash flow and that more than half have lost at least 10,000 dollars in opportunities because of it. Surplus automation parts may not be the only cause, but they contribute to the same constraint.

Beyond direct cost, there is the risk side. Firmware ages. Regulatory requirements shift. Safety standards tighten. A part that is valuable this year can turn into a liability the next. You also incur operational drag: crowded stores, inaccurate inventory data, and increased risk of counterfeit or mispicked parts finding their way into critical repairs.

Doing nothing has a price tag. Liquidation services are simply a structured way to stop paying it.

Main Liquidation Service Models For Automation Parts

Different liquidation services exist because not every seller has the same goal. Some need cash and floor space in weeks. Others want to optimize returns over months on a large pool of long tail stock. The right answer is almost always a mix rather than a single tactic.

The main models used today for automation parts look roughly like this:

| Service model | Typical speed | Typical value recovery vs market value | Best fit use case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outright purchase by surplus buyers | Fast, days to a few weeks | Lower, often single digit to low double digit percentages according to asset type | Quick cash and space, low internal bandwidth |

| Consignment and managed remarketing | Medium to long, months | Medium, up to around half of market value in some programs | Large, diverse MRO stock, long tail parts |

| Direct marketplace listings/auctions | Variable, weeks to months | Higher, often well above half of market value when demand is strong | High value, in demand items, sellers with internal resources |

| Internal redeployment, donation, recycling | Variable, process driven | Indirect financial and ESG return | Multi site fleets, strong sustainability goals |

The ranges above are grounded in what specialist firms publish, not "list price minus a guess."

Automa.Net reports that when they buy surplus automation parts outright, they typically pay about 3 to 20 percent of market value depending on condition, packaging, production year, and demand, and they handle transport and pickup. Under a consignment model, where the client retains ownership and Automa.Net manages storage, pricing, and marketing, returns can reach roughly 50 percent of market value for suitable stock. When sellers list on their marketplace themselves, they often achieve around 75 to 85 percent of market value.

Goospares, a B2B spares marketplace, reports case studies where structured liquidation of slow moving stock improved seller realization value by about 40 percent, increased buyer margins by about 60 percent, and completed liquidation within 3 months.

United Industries notes that selling surplus equipment (not just parts) can recover roughly 40 to 70 percent of the original equipment investment while eliminating carrying costs. Holland Industrial Group references a 2023 report showing that industrial auctions regularly outperform private sales by about 15 to 30 percent in realized prices.

With that context, the tradeoffs between models become clearer.

Outright Purchase By Specialist Surplus Buyers

Outright sale to a surplus buyer is the most straightforward liquidation service. You send a parts list, receive a bid, ship the goods, and collect a payment.

VB Industrial Supply describes a typical process for industrial automation and electrical components. Sellers complete a quote form with part numbers, quantities, and condition, send it by email, receive a quote usually within one or two business days, and if they accept, the buyer provides shipping labels, manages logistics, and issues payment by ACH or check, often on the day items are received.

Automa.Net follows a similar pattern on a larger, multi vendor scale. Many other buyers that focus on specific brands, such as Allen Bradley surplus, work in comparable ways.

The obvious advantage is speed and simplicity. There is no need to learn auction rules, no need to answer individual buyer questions, and no need to manage dozens of small shipments. If you are closing a plant or clearing a cage before a new line arrives, this matters.

The cost is in recovery rate. Research from Automa.Net and Microflex shows that liquidation in this sense is the lowest margin option. You trade price for time and reduced operational effort. Because buyers like VB or Allen Bradley specialists still carry risk on condition and resale, they must bid conservatively.

In practice, this model is well suited to:

- urgent floor space or cash needs

- mixed lots where you do not have the bandwidth to segment high and low value items

- brands and part families where you can benefit from a buyer's specialized knowledge

It is less suited if your primary goal is to maximize price for a small number of high value, in demand items.

Consignment And Managed Remarketing

Consignment sits in the middle of the spectrum. You remain the owner but hand most of the work to a specialist.

Automa.Net describes consignment services where they manage storage, pricing, global marketing, and customer service for surplus automation inventory, often long tail MRO. They report that this can yield returns up to about 50 percent of market value for suitable stock, significantly higher than an outright buyout, though slower to realize.

Charcap highlights consignment as a strategic tool particularly for furniture, fixtures, and processing equipment, but the same logic applies to control panels, MCC buckets, and cabinet level automation assemblies. A consignment partner handles listings, buyer screening, and logistics while you see improved returns over time.

Consignment works best when:

You have volume. A consignment partner needs enough inventory breadth and depth to justify cataloging, marketing, and warehousing.

You are not time critical. You can wait months for stock to convert to cash.

You want better visibility and control. Consignment reporting lets finance and operations track what is selling, at what price, in which regions.

The tradeoff is that you must accept market timing risk and partner commissions. Not every item will sell, and unsold stock still occupies either your space or theirs.

Marketplaces And Auctions

Direct marketplace listings and auctions give you the highest potential recovery, but they demand the most from your team.

Automa.Net allows sellers to list their own stock, enriched with master data and price optimization tools, reaching a base of more than 16,000 industrial automation buyers, including OEMs, machine builders, system integrators, distributors, and MRO teams. They report that sellers using this path often reach about 75 to 85 percent of market value for desirable items.

Goospares positions itself similarly for industrial spares, emphasizing detailed descriptions, images, and structured negotiation tools. Case studies on their platform showed the 40 percent improvement in seller realization value and 3 month liquidation cycle mentioned earlier.

On the auction side, Holland Industrial Group explains how industrial auctions create competitive bidding that usually beats private sale prices by roughly 15 to 30 percent, and highlights examples where CNC equipment sold for 80 to 90 percent of market value via auction versus 40 to 50 percent in private offers. GreenBidz describes manufacturers buying surplus machines at 30 to 70 percent lower upfront cost than new through liquidation and factory clearance auctions.

For automation parts, auction style sales are especially effective for:

- large, coherent lots such as full MCC lineups, drive cabinets, spare robot arms, or complete PLC systems

- high demand, recognizable brands and product families

- situations where you want the market to discover price rather than guess a number in isolation

The downsides are volatility and workload. Prices are not guaranteed, especially for niche items. You must invest in cataloging, photography, and description quality. You must coordinate shipping and often handle more complex terms for exports, buyer premiums, and payment structures.

Internal Redeployment, Donation, And Recycling

Not every asset should go to an external liquidation channel.

Invrecovery and Amikong both stress internal reuse and redeployment as a first filter. Before selling spares, you should check whether another plant within your group is buying the exact same models at full price. A centralized register of surplus, with make, model, serial, condition, and service history, makes this practical. Amikong recommends actively redeploying usable spares across facilities and retaining only those parts with a documented risk mitigation rationale and quantity limit.

Where external sale is not attractive, donation and recycling are valid tools. Intuendi and Microflex both highlight donations of excess inventory to charities or schools as a way to clear space, improve brand reputation, and, in some jurisdictions, capture tax benefits. Invrecovery emphasizes that donation is also a way to support sustainability goals while avoiding waste.

For genuinely obsolete or nonfunctional electronics, recycling through certified e waste vendors is both a compliance requirement and a brand protection step. Amikong notes the importance of chain of custody documentation and data sanitization for PLCs, HMIs, industrial PCs, and IIoT devices before they leave your control.

In practice, a mature surplus program will combine internal redeployment, selective external liquidation, and responsible donation or recycling.

Preparing Your Surplus Automation Stock For Liquidation

Liquidation services work best when you do your homework. The same partners who can be powerful allies can only make decisions based on what you give them.

Build The Right Inventory Baseline

Good asset recovery begins with a clear picture of what you really have.

Charcap recommends a full inventory of underused equipment, tracked in a shared system, so everyone sees the same truth. Wesellstocks advises automation sellers to compile a detailed catalog for each surplus item, including manufacturer, model number, key specs, and any unique features.

Amikong and VB Industrial Supply go further, recommending a centralized register that captures make, model, serial numbers, condition, hours where relevant, photos, manuals, and service history. VB suggests first sorting by brand and condition, then prioritizing high demand brands such as Allen Bradley, Siemens, Omron, and Schneider Electric.

In my projects, the most effective teams treat this as a recurring discipline, not a one time event. Annual or even quarterly surplus reviews aligned with budget cycles prevent surprises.

Segment And Prioritize Surplus

Once you see the whole pile, the next step is deciding what to do with each slice.

Amikong recommends an ABC style analysis for control inventories. Class A items are high value and high impact; they deserve tight controls and more frequent review. Class B parts sit in the middle. Class C items are low value and high volume and are often prime liquidation candidates, after you check reuse potential across sites.

Microflex and Omniful, looking at excess stock more broadly, encourage clear internal definitions for when an item becomes "excess" or "slow moving", often using aging buckets or turnover thresholds. Omniful suggests flagging items that have sat beyond a set number of days so they can be considered for clearance or liquidation.

The point is to avoid treating every spare as equally important. Critical spares for active lines should be protected. Aging, duplicated, or noncritical spares should be channeled toward recovery.

Valuation And Pricing Expectations

The most contentious part of any liquidation conversation is price. Having realistic expectations avoids stalemates.

Amikong notes that used controls typically sell for about half or less of the new price, depending on age, condition, brand, and demand. Some late model discontinued PLC modules can even command premiums when demand is strong and OEM support has ended, while commodity sensors trade at deeper discounts.

United Industries reports that selling surplus equipment can recover around 40 to 70 percent of original equipment cost. Aaron Equipment, which focuses on machinery, recommends pricing used equipment at about half the cost of comparable new machines as a starting point, then adjusting for market conditions and data from actual transactions. They operate their own Blue Book based on thousands of sales to support this.

For automation parts specifically, the Automa.Net numbers provide a useful anchor. An outright buyout at about 3 to 20 percent of market value is a liquidity play. Consignment, with returns around 50 percent of market value for the right items, trades time and complexity for improved recovery. Marketplace or auction listings, where returns in the 75 to 85 percent range have been reported for some items, demand the most effort and time but deliver the best realized prices when demand is strong.

The practical takeaway is simple. For each part or group, decide whether you care more about time or money, then match it to a channel with realistic expectations.

Condition, Testing, And Documentation

Surplus buyers and secondary market customers live with asymmetric information. They do not know how your parts were stored or whether your test bench is rigorous. When that uncertainty is high, they price low.

Amplio, which specializes in helping companies sell surplus Allen Bradley equipment, highlights this as a root cause of low offers. They recommend short professional appraisals and documented testing to provide objective proof of functionality. For PLCs and drives, that means boot to run tests, pulling fault histories, verifying firmware revisions, and logging results. For sealed items, it means proving that boxes are legitimate, unopened, and traceable.

Excess Logic, which deals with used lab and pharmaceutical equipment, stresses verifying condition before purchase via inspection, photos, and videos. The same diligence on the sell side builds trust and supports higher bids.

Good documentation almost always pays for itself. That includes:

- clear condition grading such as new, new open box, used tested, used untested, or for parts only

- photos that show model tags, terminal blocks, and any wear

- maintenance or repair records where available

- manuals, wiring diagrams, and any accessories that ship with the unit

Aaron Equipment notes that thorough cleaning, minor repairs, and complete documentation improve buyer perception and can justify higher asking prices for larger machines. Industrial parts behave the same way in the secondary market.

Compliance, Data Security, And ESG

For modern automation parts, data and compliance are not afterthoughts.

Amikong stresses chain of custody, data sanitization, and secure handling as part of any formal asset recovery program. Before you liquidate PLCs, HMIs, industrial PCs, or network gear, configuration files, recipes, and logs should be wiped according to your cybersecurity and quality standards. This is not only about process know how; it is also about privacy and safety.

On the environmental side, Invrecovery and United Industries describe surplus programs that cut waste by roughly 30 to 50 percent through reuse and redeployment. Microflex, Intuendi, and Charcap all highlight donations and responsible recycling as ESG aligned ways to dispose of unsellable or low value stock while improving community perception and sometimes unlocking tax benefits.

If your company has ESG targets, these aspects should sit in the same playbook as pure financial recovery, not in a separate CSR report.

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment