-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Warranty Coverage Options for Surplus PLC Equipment

When a production line is down and a legacy PLC module fails, most plants do not have the luxury of waiting twelve weeks for a new OEM part. Surplus hardware keeps a lot of older lines alive, and as a systems integrator I have leaned on that channel more times than I can count. The real question is not just whether the used or refurbished PLC will run today, but who pays if it dies three months into a critical production run.

That answer lives in the warranty, and with surplus PLC equipment the warranty landscape is very different from buying new hardware. Manufacturer coverage is often gone, reseller policies vary widely, and a long list of exclusions means many “failures” will be on your budget, not theirs. This article walks through what is actually covered on surplus PLCs, where the traps and blind spots are, and how to combine warranties with good maintenance to protect your plant.

Why Warranty Terms Matter More With Surplus PLCs

A programmable logic controller is not just another box on the DIN rail. As Coast and eWorkOrders point out in their maintenance guides, PLCs sit at the heart of automated lines, coordinating sensors, motors, valves, and safety functions. When a PLC fails, you are not losing a single component; you are often losing an entire production area.

New PLCs typically ship with a factory warranty of around twelve months on the hardware, similar to the machinery coverage highlighted by Machine Guard. Used machinery often has far less, sometimes only about three months. For surplus PLC hardware, the picture is different again. Independent distributors such as Industrial Automation Co. and PLC Department step in with their own warranties on used, refurbished, and surplus parts, but they also make it clear that the original manufacturer’s warranty does not apply and that factory-level technical support may not be available.

In other words, when you buy surplus PLC equipment, the warranty you have is the one written by the surplus seller, not the OEM. That makes it essential to treat the reseller’s policy as part of the technical specification, not as an afterthought to be skimmed after the purchase order is cut.

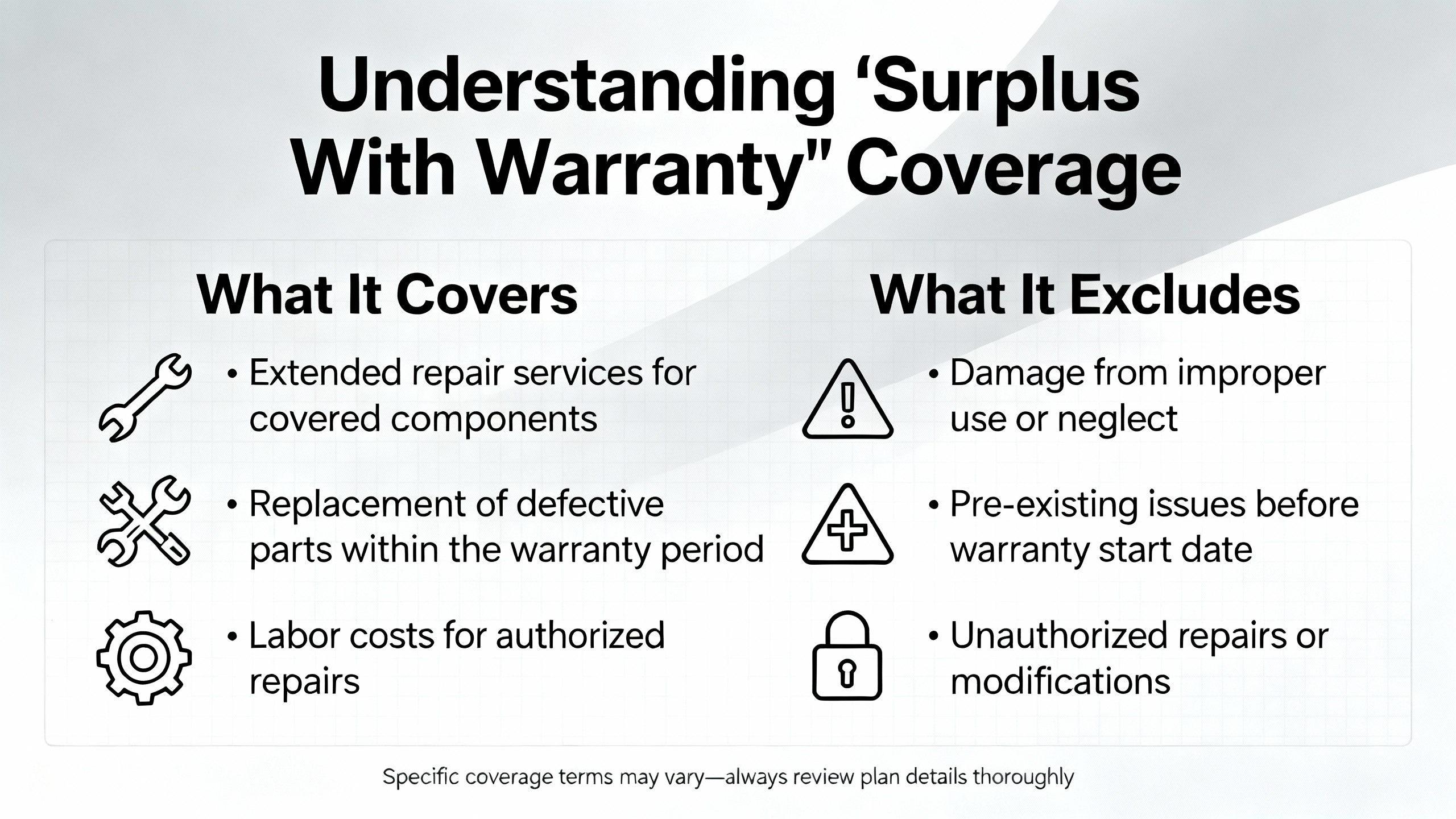

What “Surplus With Warranty” Really Covers

Surplus PLCs are sold in different conditions. PLC Department, for example, describes all items as “Surplus – Tested (With Warranty)” and further breaks that into new surplus, used surplus, and refurbished surplus. New surplus might be inventory that was never installed; used surplus has been in service but has been tested as working; refurbished surplus has been repaired or reconditioned. Cosmetic imperfections and missing original packaging are expected, but functions are verified.

Across multiple surplus suppliers, the warranty promise is similar on the surface. The equipment is warranted to be free of defects in materials, workmanship, or internal components when used as intended. Industrial Automation Co. provides a two‑year warranty on all items bought from them, warranting products to be in good working order and free from internal component defects. plcpartsstore specifies a twelve‑month warranty for new equipment and a six‑month warranty for used or refurbished units, in both cases covering manufacturing defects under normal, recommended use. PLC Department offers a one‑year product warranty on all items, covering mechanical defects and failures that are not caused by human factors such as incorrect installation or poor maintenance.

Several common threads run through those examples. The warranty is tightly tied to manufacturing or internal defects, not to how the unit is installed or how harsh the environment is. The coverage applies only when the product is installed, operated, and stored according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. And every one of these policies puts strict boundaries around what counts as a warrantable failure.

Typical Duration and Scope of Surplus PLC Warranties

The table below summarizes the kind of warranty terms you will encounter in the surplus PLC market, based on the published policies of several suppliers.

| Supplier example | Product types | Standard warranty duration | Core coverage focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial Automation Co. | Used, refurbished, surplus automation | 24 months from purchase | Internal component defects, good working order at sale |

| PLC Department | Surplus tested PLC and automation | 12 months from purchase | Mechanical defects not caused by human factors |

| plcpartsstore | New, used, refurbished PLC products | 12 months new, 6 months used/refurb | Manufacturing defects under normal use |

| PLC Products Group | Company‑branded hardware | 12 months from purchase | Defects in materials and workmanship |

Each of these suppliers stands behind its own testing and refurbishment processes, but none of them promises OEM‑level quality control, and several explicitly state that they are independent resellers, not authorized distributors. That is not a problem in itself, but it reinforces the point that your real protection is the reseller’s warranty language and your own practices, not the original factory warranty.

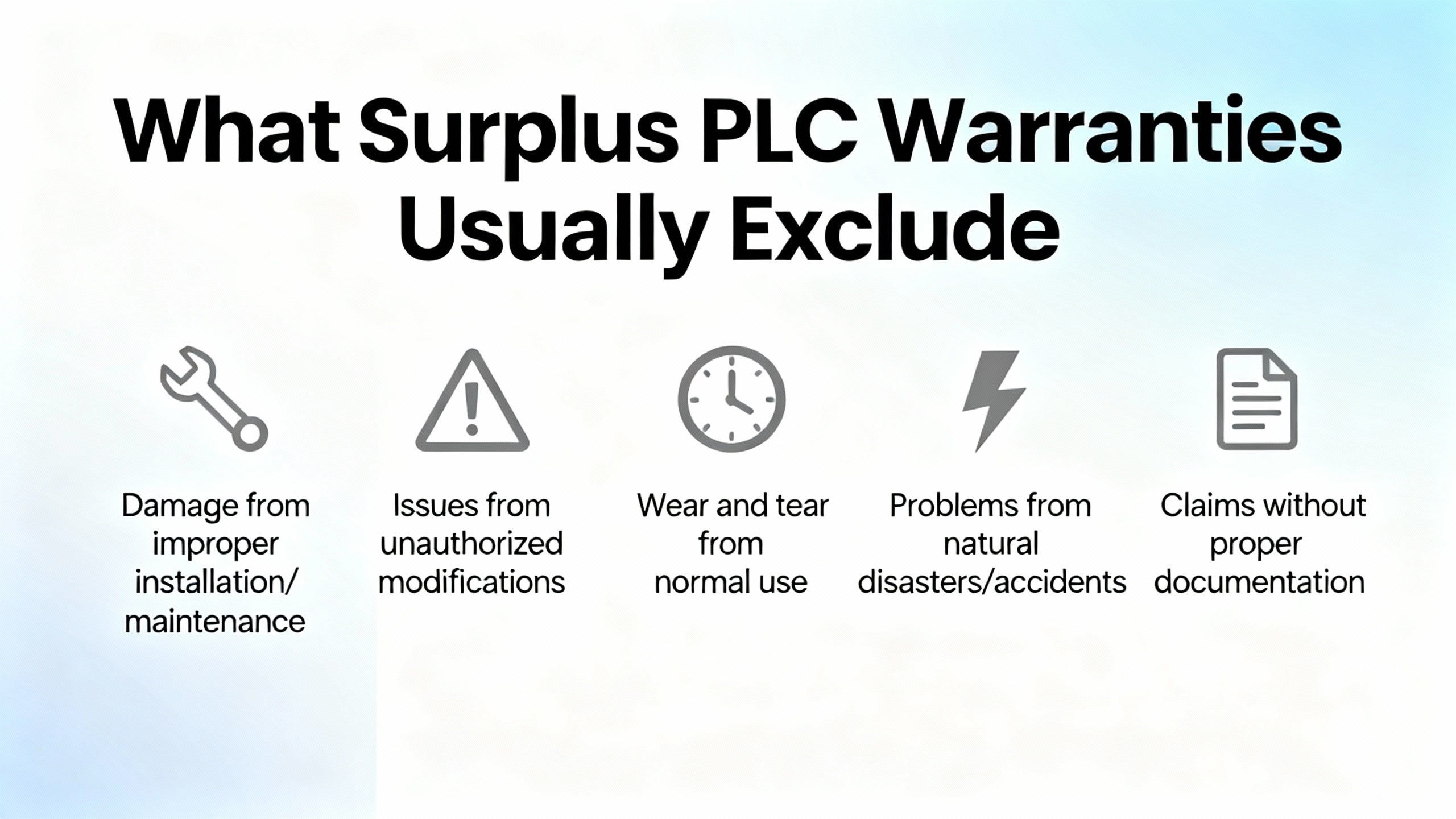

What Surplus PLC Warranties Usually Exclude

The real story is in the exclusions. Surplus PLC warranty pages devote far more space to what is not covered than to what is. PLCpartssolution and plcpartsstore both publish detailed lists that are representative of the industry.

Improper installation sits at the top. If you do not follow the manufacturer’s specifications for mounting, wiring, or configuration, coverage will not apply. Abuse, misuse, and neglect are also excluded, including unauthorized modifications, accidents, and any use beyond rated voltage, current, or speed. Physical damage during transport, such as scratches, dents, and impact damage, is generally treated as a shipping issue, not a warranty event.

Electrical and environmental conditions appear repeatedly. Failures caused by unstable, incorrect, or inconsistent power input are excluded. So are malfunctions caused by electrical interference such as EMI and RFI, inadequate grounding, moisture or corrosive environments, poor ventilation, overheating, and excessive mechanical vibrations. If the host machine connected to the PLC causes a failure, that is also excluded. Industrial Automation Co. adds familiar force‑majeure language to that list, excluding accidents, natural disasters, power surges, acts of God, vandalism, and insufficient maintenance.

Unauthorized repairs are another consistent red line. PLCpartssolution, plcpartsstore, and PLC Products Group all make it clear that tampering with internal components, replacing boards without authorization, or obtaining service from non‑authorized providers can void warranty eligibility. PLC Department draws a similar line by stating that human‑caused faults fall outside its coverage and become the customer’s responsibility.

When you put those exclusions against real plant conditions, you can see why warranty coverage is narrower than many buyers assume. Most in‑field PLC failures are tied to environment, power quality, wiring, or software changes, not to a latent defect in a passive component. Guides from eWorkOrders, EEWorld, and PDFSupply all stress that dust, thermal stress, humidity, poor grounding, and loose terminations are leading causes of PLC problems. Those are precisely the conditions that surplus warranties exclude.

From an integrator’s perspective, the conclusion is straightforward. You should treat surplus warranties as protection against early life failures of the refurbished hardware itself, not as an insurance policy against poor design, sloppy installation, or harsh environments.

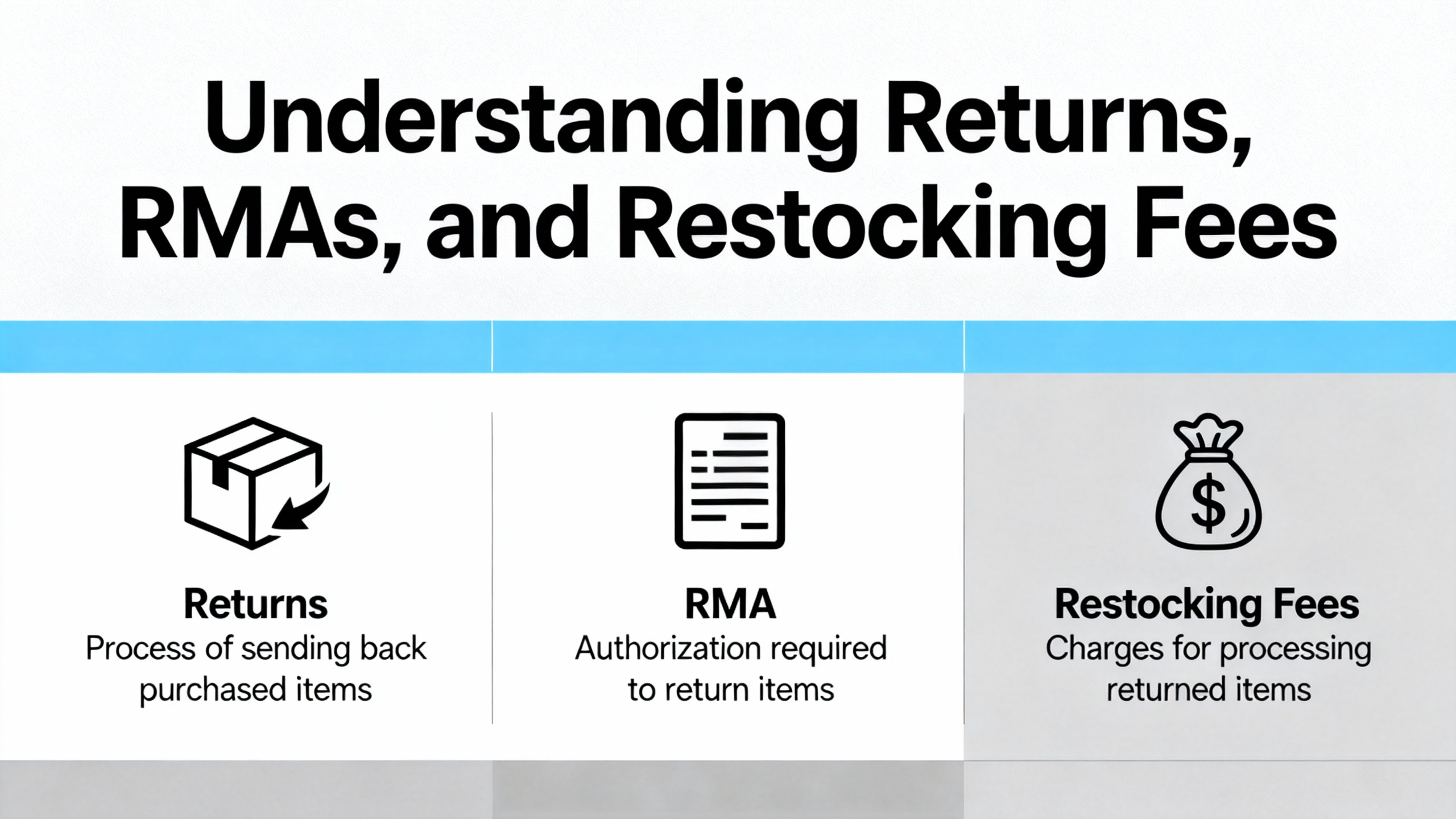

Returns, RMAs, and Restocking Fees

Surplus PLC warranties do not operate like “no questions asked” retail returns. There is a clear separation between warranty returns for defective units and non‑warranty returns when the unit is working but not needed.

Industrial Automation Co. allows non‑warranty returns only within thirty calendar days of delivery, requires proof of purchase and an RMA number, and applies a twenty‑five percent restocking fee. Shipping charges are not refunded, and orders canceled after shipment can incur that same restocking fee. PLC Department offers a thirty‑day return window on surplus units if the customer is not satisfied, but repairs, replacements, and refunds under warranty are handled only after the returned item has been diagnosed by their technicians. PLC Products Group requires customers seeking warranty service to contact support, obtain an RMA, and clearly mark that number on the outside of the package, while also providing proof of original purchase with product description, dates, and serial numbers.

plcpartsstore and PLCpartssolution both require customers to initiate warranty claims by email, typically including order details, serial numbers if available, descriptions of the issue, and supporting photos or videos. Their teams evaluate whether the failure fits within the stated warranty scope and then decide whether to repair, replace, or refund.

In practical terms, that means you should plan for at least three elements. First, someone on your team must gather and preserve documentation such as receipts, packing slips, and serial numbers. Second, you need realistic expectations about time to resolution; sending a PLC across the country for evaluation does not help you restart a line tomorrow. Third, you should budget for shipping in both directions and, where restocking fees apply, for a percentage loss if you change your mind after a unit has shipped.

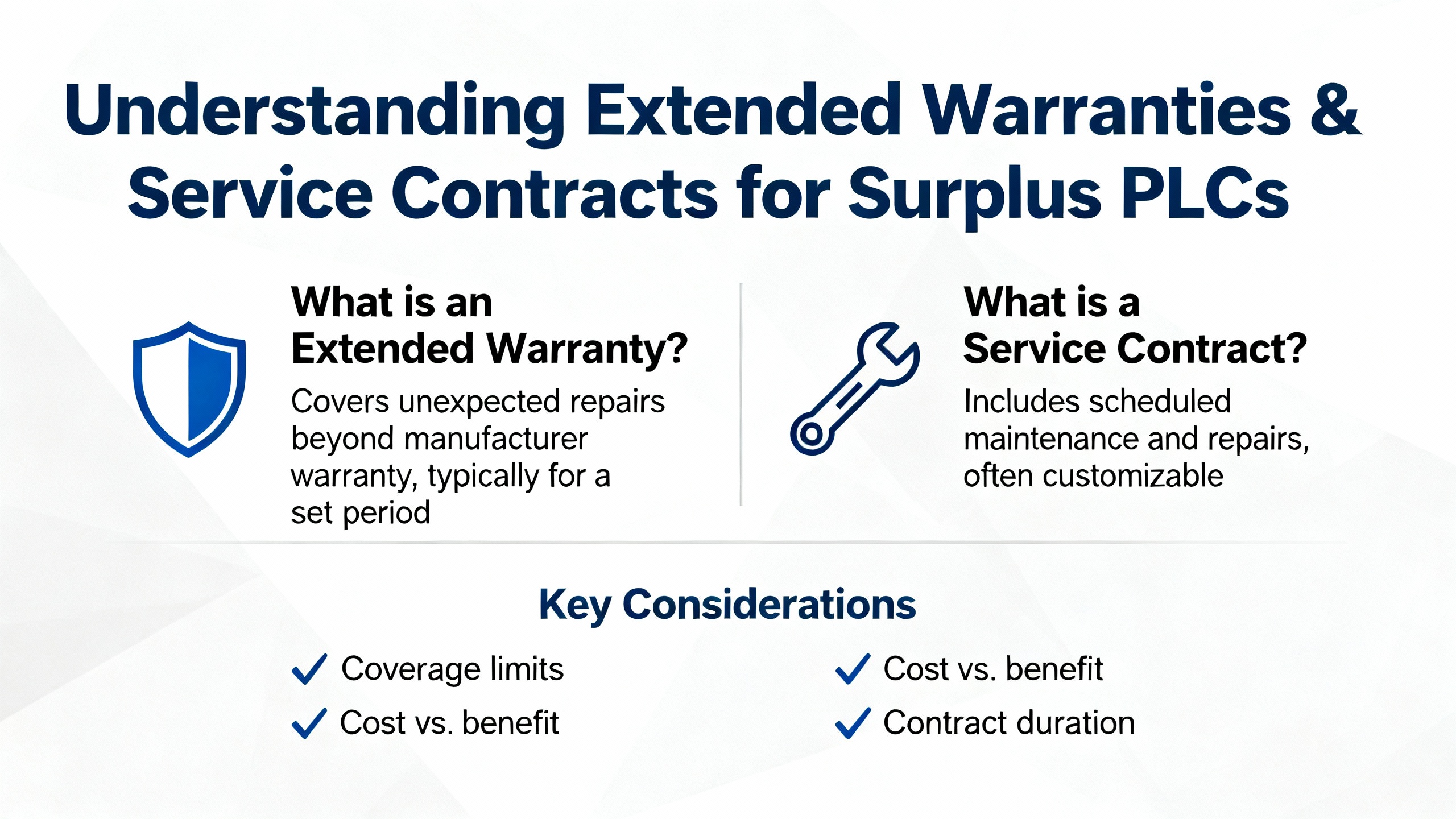

Extended Warranties and Service Contracts Around Surplus PLCs

In industrial automation, warranty and service contract are not the same thing. Qviro’s automation warranty guide draws that distinction clearly. A warranty is the supplier’s written promise that the product will perform as expected for a defined period, usually covering manufacturing or design defects and early failures. A service contract or extended warranty is a separate, paid agreement that typically stretches coverage beyond the standard term and may add wear‑and‑tear coverage, preventive maintenance, or faster support.

Machine Guard describes how standard factory warranties on new machinery often expire after about twelve months, leaving the bulk of the machine’s life uncovered, while used machinery may have only about three months of manufacturer coverage. Their extended warranty offering is an example of a program designed to bridge that gap, with conditions such as requiring genuine manufacturer parts in all repairs.

Qviro notes that standard industrial automation warranties are often around twelve months and that some extended options push coverage out to about twenty‑four months, sometimes including parts, labor, and even travel. They also point out that extended warranties can be financially justified when the equipment is mission‑critical, heavily used, remote, or expensive to access. In those cases, paying from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars for extended coverage can be cheaper than a single major out‑of‑warranty failure on a high‑value component like a robot arm, sensor package, or controller.

Consumer‑oriented research from FasterCapital raises the other side of the ledger. Extended warranties can be costly relative to the asset value, may offer limited or selectively defined coverage, and can overlap with existing warranties or legal protections. Their example of a multi‑hundred‑dollar plan on a laptop illustrates how easy it is to overpay for marginal extra protection.

For surplus PLCs, the pattern is similar. Some automation suppliers and integrators bundle service contracts that include extended coverage for refurbished controllers and I/O, along with periodic inspections and priority support. Others leave extended coverage to third‑party providers. In either case, the logic for buying or skipping extended coverage is the same as for new equipment, but the stakes are higher because manufacturer coverage is often absent. A used PLC with only six months of reseller warranty sitting at the center of a high‑value, twenty‑four‑hour line is a very different risk profile from a surplus PLC on a lab test rig.

When you see an extended warranty offer around surplus equipment, the key questions are scope, price, and conditions. The guidance from Sirion’s analysis of warranty clauses is useful here. You should look for clearly defined coverage periods and start dates, structured remedies such as repair, replacement, or refund, and explicit exclusions and limitations. You also need clarity on whether the extended coverage is transferable if ownership changes and how repairs must be handled to remain eligible.

How Warranty Interacts With Installation and Maintenance

One of the consistent themes across the surplus warranty policies is that failures tied to environment, power, or misuse are not covered. At the same time, PLC maintenance guides from Coast, eWorkOrders, EEWorld, and PDFSupply emphasize that those same factors drive most control system failures. That is not a coincidence. Warranties are written around the assumption that you, as the owner or integrator, will manage these risks.

Environmental conditions are the first line of defense. EEWorld recommends keeping PLC control cabinet temperature within the typical 32–104°F range, with humidity below about eighty‑five percent, and avoiding environments with heavy dust, salt, or metallic filings. eWorkOrders and Solution Controls both highlight the need for clean, unobstructed ventilation paths, regular replacement of cabinet air filters, and removal of dust and debris from CPUs and I/O modules to prevent overheating and shorts. If your cabinet fan filters are clogged, if manuals and tools are stacked on top of enclosures, or if panels are installed next to heat sources or in high‑vibration zones without mitigation, you are not just risking downtime; you are also handing the supplier a reason to deny warranty coverage.

Power quality and grounding are just as important. EEWorld’s guidance calls for verifying stable 24 VDC outputs, checking insulation integrity with proper instruments, and ensuring that cable lugs and large conductors are tight and free from discoloration that indicates overheating. PDFSupply adds recommendations about measuring operating current against reference values and monitoring AC ripple on DC outputs. Surplus warranty policies draw these lines clearly when they exclude failures caused by unstable or incorrect power, improper electrical operation outside rated limits, and inadequate grounding.

Software and data practices have a warranty dimension as well. Multiple maintenance sources stress the importance of regular program backups, version control, and verification of logic correctness. PLC Products Group instructs customers to back up all software and data before service and explicitly excludes liability for any loss of programs or data during repairs. If you treat PLC backups as optional, you may restore hardware under warranty but find yourself absorbing the cost of extended downtime while code is rebuilt.

Finally, there is the boundary around authorized repairs. PLCpartssolution and plcpartsstore state that unauthorized repairs, tampering with internal components, or replacing boards on your own void coverage. PLC Products Group excludes damage from service or upgrades performed by non‑authorized providers and modifications without written permission. That does not mean every minor intervention requires OEM involvement, but it does mean you should understand where your supplier draws the line and avoid “creative” fixes that could jeopardize coverage.

In practice, the best way to keep both your plant and your warranty intact is to fold PLC care into your broader preventive maintenance program. eWorkOrders and Coast recommend using a computerized maintenance management system to schedule tasks such as dust removal, filter changes, inspections of connections and grounding, and regular checks of error logs and diagnostic buffers. When those activities are documented and aligned with manufacturer recommendations, you reduce both real failure risk and the likelihood of a disputed warranty claim.

Choosing Between Surplus Warranty Options

When you are choosing between surplus PLC sources, the decision is not just about price and delivery. You are also choosing a risk‑sharing partner for the next six to twenty‑four months. It can be helpful to think in terms of three dimensions: duration, scope, and process.

Consider a scenario with three offers that mirror the policies discussed earlier. One distributor offers a two‑year warranty on any unit you buy, but that coverage is limited strictly to internal component defects, excludes a broad range of external causes, and comes with a twenty‑five percent restocking fee on non‑warranty returns. A second surplus specialist offers a one‑year warranty on “surplus – tested” units, covering mechanical defects that are not caused by installation issues or poor maintenance, and provides a thirty‑day satisfaction return policy. A third seller differentiates between new surplus and used surplus, offering twelve months of coverage on the former and six months on the latter under normal use.

Which one is “best” depends on your situation. For a line that is stable, well‑maintained, and not running on the edge, a shorter but simpler warranty might be sufficient if you value easier returns and a more flexible relationship. For a mission‑critical process where you cannot afford to eat the cost of an early hardware failure, a longer hardware‑only warranty can be valuable even if the exclusions are strict, provided you are confident in your own installation and maintenance practices.

Sirion’s research on warranty clauses adds another important insight. They report that more than a third of contract disputes stem from poorly drafted warranty clauses, and that standardized, clearly defined warranty provisions can significantly reduce litigation costs. Translated into the surplus PLC world, that means vague statements such as “normal wear and tear” or unclear definitions of “proper use” are red flags. FasterCapital’s analysis of consumer warranties reaches the same conclusion from another angle, warning that ambiguous language, excessive exclusions, unreasonably short or suspiciously long coverage periods, and complex, documentation‑heavy claims processes can strip a warranty of practical value.

As a systems integrator, I treat the warranty document as a technical spec. I read it fully before committing, I make sure the buyer understands what is and is not covered, and if I am reselling equipment downstream, I align my own commitments with what I can reliably claim upstream. The Global Supply Chain Law guidance on “back‑to‑back” warranties is directly applicable here. If you promise your customer a broader warranty than your supplier gives you, you are taking on a risk that may be hard to insure or price.

When Extended Coverage Makes Sense for Surplus PLC Equipment

Extended coverage around surplus PLCs is not automatically a good or bad idea. It is a tool, and like any other tool, it is useful only in the right context.

Qviro’s analysis suggests that extended warranties are most justified where equipment is mission‑critical, heavily used, remote, or expensive to access. Those are exactly the conditions where PLC failure is most painful. If a refurbished controller sits in a remote pumping station that requires a day of travel to reach, or in a continuous process line where an hour of downtime costs more than the hardware itself, the economics change. Paying for extended coverage or a service contract that includes rapid response and pre‑positioned spares can be rational.

On the other hand, if your surplus PLC drives a non‑critical test stand, runs only a few hours a week, or can be swapped out easily from spares, the standard six‑to‑twelve‑month warranty may be enough. FasterCapital’s warning about paying for overlapping or low‑value coverage applies here as well. If the extended plan adds little beyond what you already have in the base warranty and your own maintenance capability, the money is usually better spent on spare parts and in‑house skills.

Machine Guard’s requirement that only genuine manufacturer parts be used under their extended warranty programs highlights a final consideration. Some extended coverage offerings impose strict rules about parts sources and repair procedures. If you rely on local repair shops or keep a stock of third‑party compatible parts, those conditions may clash with how your plant actually operates. You need to know up front whether extended coverage will require you to change established maintenance practices.

Coordinating Warranty With Your Maintenance and Spares Strategy

Warranty language and maintenance practices are two sides of the same coin. Maintenance guides from PLCDepartment, PDFSupply, and others emphasize keeping detailed documentation, backing up programs, logging maintenance actions, and maintaining a spare‑parts inventory that includes at least one spare CPU and power supply and, for critical systems, even a complete standby rack. DO Supply’s MicroLogix troubleshooting guide reinforces the value of having spare controllers, I/O modules, and batteries on hand for fast replacement.

From a warranty standpoint, good documentation does two things. It helps you diagnose whether a problem is truly a hardware defect, and it gives you evidence when you make a claim. If your CMMS records show that the cabinet environment stayed within recommended limits, that connections were inspected and tightened regularly, and that no unauthorized modifications were made, you are in a stronger position to argue that a failure is due to an internal defect rather than misuse.

At the same time, a realistic spares strategy prevents you from relying on warranty logistics to get back online. Even with a cooperative supplier, RMA processing, shipping, and testing all take time. In critical applications, warranty coverage should be viewed as cost protection, not as your primary availability strategy. Your real first line of defense is a combination of proper engineering, preventive maintenance, and a thoughtful spare‑parts plan.

Short FAQ on Surplus PLC Warranties

Does buying surplus PLC hardware always void the manufacturer’s warranty?

Many surplus distributors explicitly state that factory warranties do not apply to their products. Industrial Automation Co. is clear that manufacturer warranties are void on items purchased from them, and PLC Department positions itself as a surplus reseller, not an authorized distributor. You should assume that your coverage comes from the reseller’s policy, not the OEM, unless you have written confirmation to the contrary.

Is a longer warranty always better?

A longer term looks attractive, but duration is only one piece of the puzzle. Sirion’s research on warranty clauses and FasterCapital’s practical guidance both show that vague language, extensive exclusions, and difficult claim procedures can make even a multi‑year warranty worth much less than it appears. A clear twelve‑month warranty with straightforward remedies and reasonable exclusions can be more valuable than a longer warranty that excludes most real‑world failure modes in your plant.

How can I keep my surplus PLC warranty valid?

The surplus warranty exclusions align closely with the maintenance best practices described by EEWorld, eWorkOrders, Solution Controls, and others. If you follow manufacturer installation instructions, maintain proper environmental conditions, ensure stable power and grounding, avoid unauthorized repairs, and document your maintenance activities, you are both reducing the chance of failure and staying within the conditions most suppliers require for coverage. Ignoring cabinet cooling, running beyond ratings, or making undocumented modifications will not only increase failure risk but also give your supplier strong grounds to deny a claim.

Should I buy extended warranty or a service contract for surplus PLCs?

The decision depends on how critical the PLC is, how harsh the environment is, and how strong your internal maintenance capability is. Qviro’s and Machine Guard’s guidance suggests that extended coverage is most justified for mission‑critical, high‑duty, or remote installations where downtime is very expensive. FasterCapital’s caution about cost and overlap reminds you to compare the price and scope against the base warranty and your own ability to manage risk. If you already have robust spares, disciplined maintenance, and good diagnostics, you may get more value from investing in those areas than from a generic extended plan.

In the end, surplus PLC warranties are neither a silver bullet nor a trap if you treat them with the same rigor as any other engineering decision. Read the terms carefully, match them to your risk profile, and back them up with solid maintenance and documentation. That combination is what keeps production running and surprises off your downtime reports.

References

- https://www.plchardware.com/product-conditions.aspx?srsltid=AfmBOorNH3ze90NFMPxqUtmcDVC8ahuCb0O-r8qYEuv9hrKjPnds9w7a

- https://plcproducts.com/warranty

- https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/8-382-3760?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)

- https://constructionequip.com/heavy-equipment-parts-warranty-coverage/

- https://www.cpscentral.com/tools-protection-plan/

- https://www.expertia.ai/career-tips/dos-and-don-ts-of-plc-maintenance-in-industrial-automation-20406i

- https://fastercapital.com/content/Ensuring-Peace-of-Mind--Examining-Warranty-Agreements-in-Sales-Contracts.html

- https://industrialautomationco.com/pages/warranty-information?srsltid=AfmBOopZf_CSSRUBsvHsYe2o4fd1SKh0SG7w3DWmPulkASETaHJB0rmr

- https://www.plcdepartment.com/pages/frequently-asked-questions-faq?srsltid=AfmBOoqp-ZSHbN9d-aWJ6GkmqbZwvuHLT7E-sz_1mGUg2QzOme9d3JIp

- https://plcpartssolution.com/pages/warranty-policy-1?srsltid=AfmBOooZLd4IUJ2ljADxCTfyqoYLf4bzyaDgF43o61jOW33e6LcwtpFn

Keep your system in play!

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment