-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

UL and CE Certified Control Components: A Practical Field Guide to Global Market Compliance

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

As a systems integrator, nothing kills a project faster than a control panel that fails inspection at the eleventh hour. I have seen perfectly good automation designs stuck on a loading dock because a critical component did not carry a recognized UL mark, or a machine held at a European border because the CE documentation was incomplete. The hardware might work flawlessly, but without the right certification story, it simply does not exist in that market.

This article walks through how UL and CE certified control components really work in the field, how they differ, and how to design panels and control systems that pass inspection in North America, Europe, and beyond. The focus is pragmatic: what matters for control hardware, control panels, industrial PCs, and the components that tie them together.

Why Certification Matters In Control Systems

In industrial automation, certifications are not just logos on a nameplate; they are formal proof that your equipment meets defined safety, quality, and performance standards. Independent sources like Unex and 4C Consulting describe certifications as structured procedures that verify compliance with national and international standards, reduce safety risks, and smooth international market access. In the control world, that translates directly into fewer surprises with Authorities Having Jurisdiction (AHJs), fewer arguments with insurers, and fewer late-stage redesigns.

For electrical and control equipment, several themes repeat across reputable sources such as UL Solutions, C3 Controls, and European Commission guidance. Certification reduces the risk of fire, electric shock, and mechanical failure. It smooths approvals with inspectors, especially when they recognize the mark, and it shows customers that your panel shop or OEM is serious about safety rather than relying on marketing promises.

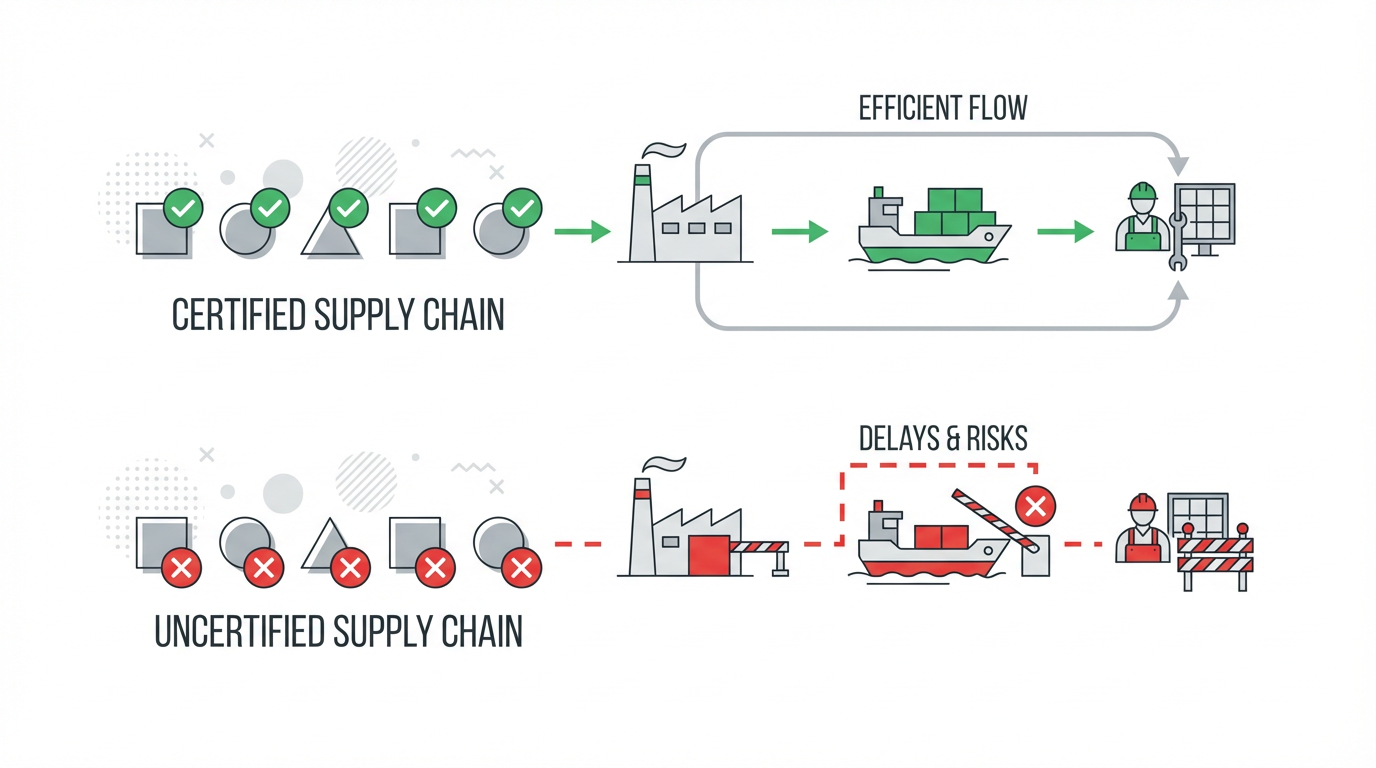

There is also a business reality. UL and similar marks are recognized globally; roughly tens of billions of UL-marked products reach the market each year, and CE marking is legally required for many products in the European Economic Area. That means certified components generally move more easily through supply chains, are easier to insure, and are far less likely to trigger an expensive field evaluation or retrofit.

UL And CE In Plain Language

Engineers often talk about “UL” and “CE” as if they were interchangeable safety badges. They are not. They serve different roles and are built on very different processes.

UL: Independent Safety Certification

Underwriters Laboratories is a U.S.-based, independent safety science organization dating back to 1894. It develops standards and certifies products against them. UL and related marks (including UL Listed, UL Recognized Component, Classified, and Performance Verified) indicate that representative samples of a product have been evaluated to defined safety standards and that the manufacturer is under ongoing surveillance.

Several characteristics are consistent across descriptions from UL-focused articles and industrial case studies. UL certification is typically optional in U.S. law for many products, but it is widely required or expected by AHJs, insurers, and large buyers. It relies on third-party testing and inspection, either directly by UL or by accredited labs under UL’s oversight. It is not a blanket approval for every possible use; it confirms that specific constructions, ratings, and conditions of acceptability have been reviewed.

For control systems, UL standards matter at several levels. UL 508A governs industrial control panels. Standards such as UL 60947 apply to industrial motor and automation controls, while UL 62368, UL 61010, and related standards address information technology, measurement, and control equipment. UL’s follow-up services include unscheduled factory visits where representatives may check documentation, examine production samples, and verify that the UL mark is being used correctly. The message is clear: UL certification is an ongoing commitment, not a one-time stamp.

CE: Mandatory EU Conformity Mark

CE marking is very different in concept. According to European Commission guidance, CE is the mandatory conformity mark for products covered by specific harmonized EU rules. It indicates that the manufacturer declares the product meets relevant EU safety, health, and environmental requirements and can be marketed across the European Economic Area, as well as in countries that accept CE such as the United Kingdom for many goods, Switzerland, and Turkey.

CE marking is not a quality mark and does not, by itself, prove independent third-party testing. The process begins by identifying the applicable EU legislation, such as the Low Voltage Directive, the EMC Directive, the RoHS Directive, the Machinery Directive, or specialized regulations like the EU Battery Regulation. The manufacturer must determine which essential requirements apply, decide whether a Notified Body is required for higher-risk categories, and then carry out or commission testing.

Crucially, CE is usually self-declaration. The manufacturer compiles a technical file that includes design data, drawings, circuit diagrams, bills of materials, specifications, and test reports. They then issue an EU Declaration of Conformity and affix the CE mark. There is no central EU body that “grants” CE; the manufacturer assumes legal responsibility, and national authorities may later request documentation or enforce penalties.

For control components and panels sold into Europe, CE is about legal market access. Without it, many products simply cannot be placed on the EU market. But CE alone says less about independent verification than a UL mark.

UL Versus CE: Complementary, Not Interchangeable

UL and CE are often treated as competitors, but reputable sources such as 4C Consulting and Gletscher Energy emphasize that they solve different problems. UL is a third-party safety certification program tied closely to U.S. and Canadian codes and, in many sectors, is effectively required by AHJs and insurers. CE is a legal passport for placing products on the EU market, based primarily on manufacturer responsibility and self-declaration.

A concise way to see the difference is to compare their roles for control components.

| Aspect | UL-Certified Control Components | CE-Marked Control Components |

|---|---|---|

| Primary purpose | Demonstrate independent safety compliance to UL standards | Declare conformity with EU safety, health, and environmental law |

| Who applies the mark | UL or authorized manufacturer under UL program rules | Manufacturer or authorized representative |

| Typical evidence | UL certification report and listing in an NRTL directory | EU Declaration of Conformity and technical file |

| Where it is expected | Primarily North America; widely respected globally | Legally required in EU/EEA and recognized in related markets |

| Testing approach | Third-party testing and follow-up inspections | Self-assessment; Notified Body only for defined higher-risk cases |

| Use in projects | Satisfy AHJ and insurer expectations for safety | Allow legal sale and circulation within EU markets |

In practice, many global control projects need both UL and CE in some form, sometimes alongside IEC-based certifications or marks from other labs such as CSA or ETL that use UL and IEC standards.

UL Listed, UL Recognized, And CE-Marked Control Components

Understanding the different mark types is crucial when you are building or buying control hardware.

UL literature and manufacturers such as C3 Controls draw the line clearly. UL Listed applies to stand-alone, finished products intended for use as-is in the field. Examples include complete industrial computers, finished power supplies, motor controllers in their own enclosures, fire alarm control units, or even fully built control cabinets. A UL Listed device has been evaluated as a complete assembly for reasonably foreseeable risks of fire and electric shock in normal use.

UL Recognized Components are different. This mark applies to parts and subassemblies intended to be installed inside larger equipment. Circuit boards, open-frame power supplies, I/O modules, and barrier materials are common examples. The evaluation focuses on how these components behave within an end product, and the UL file usually includes explicit conditions of acceptability. These may require the component to be enclosed, protected from certain chemicals, or used within specific voltage, current, and temperature limits.

For industrial automation, you often see a combination. An industrial PC or HMI panel might be UL Listed as a complete device and also rely on UL Recognized internal modules. Those modules might simultaneously meet IEC 62368 or IEC 60947 requirements, aligning with both UL and international standards. CE marks can appear on the finished devices and on components that are individually placed on the EU market, but the legal responsibility for CE conformity of the overall machine or panel sits with whoever puts their name on the finished product in Europe.

In other words, UL Recognized components and CE-marked devices are tools, not endpoints.

It is the integrator or manufacturer of the finished control panel, machine, or system who owns the final UL Listing or CE conformity.

UL 508A And The Role Of Certified Components In Control Panels

When you build industrial control panels, UL 508A is the reference standard that inspectors and customers expect to see in North America. MIS Controls and other UL 508A-certified shops describe it as the rulebook for the design, assembly, and manufacture of industrial control panels.

UL 508A requires that panels use appropriate UL-listed critical components, maintain adequate electrical spacing and creepage distances, follow regional electrical codes, and include proper circuit protection. It also requires clear and consistent labeling, including the short-circuit current rating based on the lowest-rated device in the panel. Together, these requirements dramatically reduce the risk of wiring errors, insulation breakdown, or misapplied components that could lead to fire or shock incidents.

From a component standpoint, UL 508A encourages disciplined selection. Using UL Recognized power supplies, breakers, relays, motor starters, and industrial PCs simplifies the job of proving that the assembled panel meets the standard. When every critical building block already comes with a UL file and, ideally, CE and IEC documentation, your final panel certification moves faster and your documentation is easier to defend with both UL inspectors and AHJs.

There is also a market angle. A UL 508A label on a panel, backed by traceable certified components inside, sends a strong signal to corporate engineering teams and insurers. It tells them that you follow a structured, independently audited process rather than improvising from one job to the next.

CE Marking For Control Components And Panels

On the European side, the CE story for control systems revolves around correctly identifying applicable directives and standards and then documenting conformity. Electrical and electronic control equipment typically falls under the Low Voltage and EMC Directives, often alongside RoHS restrictions on hazardous substances. Machinery with integrated control systems may also be covered by the Machinery Directive or its successor regulations.

European Commission guidance and compliance specialists at 360 Compliance emphasize a few key points. First, CE marking is only allowed for products that are actually covered by EU legislation requiring it; other categories, such as pure chemical products or food, follow different regimes. Second, a single product may be subject to several EU acts at once, and the manufacturer must satisfy all of them before applying the CE mark. Third, the technical file is not optional; it must be maintained for at least ten years after the last unit is placed on the market, and authorities can request it at any time.

For many control products, manufacturer self-assessment is permitted if you follow harmonized European Norms. Higher-risk equipment, such as certain types of machinery or pressure systems, may require a Notified Body to participate in the conformity assessment. In either case, the manufacturer remains accountable for the CE mark and the Declaration of Conformity.

A practical nuance for control engineers is that CE marking often rides alongside IEC standards. For example, industrial motor and automation controls may be designed to IEC 60947, and industrial PCs may follow IEC 62368 or IEC 61010 safety requirements. Aligning with these standards from the outset not only supports CE marking but also harmonizes with UL and other certification programs, reducing duplicated testing across regions.

Designing Control Systems For Global Compliance

In real projects, the challenge is not choosing between UL and CE but orchestrating both in a way that fits your schedule and budget. Across case studies on energy storage, fire alarm systems, and industrial equipment from sources such as Jensen Hughes, Innxeon, and Gletscher Energy, a consistent pattern emerges.

The starting point is geography. Before you spec a single component, decide where the equipment will be sold and installed. North American industrial sites tend to expect UL Listed or equivalent NRTL-certified panels and may specifically call out UL 508A, UL 864 for fire alarm systems, or UL 9540 for energy storage systems. Many European jurisdictions, by contrast, are laser-focused on CE marking and the corresponding EN and IEC standards.

Once markets are clear, map the product to applicable standards. For a typical industrial control panel, that might mean UL 508A and UL 60947 on the North American side and the Low Voltage and EMC Directives plus EN 60947 in Europe. For an energy storage control cabinet, you may be looking at UL 9540 for the system, UL 1973 for stationary batteries, and CE marking under the EU Battery Regulation.

With the standards landscape defined, component choice becomes strategic. Selecting UL Recognized components that also meet IEC and CE requirements is often worth the incremental cost. Industrial PC suppliers, power supplies, and I/O vendors routinely offer products with UL, CE, and sometimes additional marks such as CSA or ETL. Using those devices simplifies both UL panel listing and CE conformity assessment.

Documentation is the next pillar. UL-focused guidance such as Dave’s Desk emphasizes the importance of schematics, bills of materials (including substitutes), PCB data, enclosure specifications with flammability and UV data, and explicit installation manuals. European CE guidance adds the technical file and Declaration of Conformity. Integrators who treat documentation as part of the design, rather than as an afterthought, consistently have fewer issues with inspectors and customers.

Finally, engage with the right third parties at the right time. For CE, that might involve a Notified Body for higher-risk machinery. For UL, it might mean working with UL or another Nationally Recognized Testing Laboratory to review your design early, especially if you are targeting demanding standards such as UL 9540. The same principle appears in medical and renewable energy case studies: early collaboration with certification bodies avoids design dead ends and compresses time to market.

Pros And Cons Of UL And CE Certified Control Components

From a project partner standpoint, using UL and CE certified control components is not free. There are trade-offs, and they need to be understood rather than hand-waved.

On the plus side, certified components reduce safety risk and legal exposure. Independent testing under UL or equivalent standards checks for electric shock hazards, fire risk, thermal behavior, insulation breakdown, and mechanical strength. In sensitive applications such as medical devices and fire alarm systems, certifications are directly tied to patient or life safety, and industry sources emphasize that insurers and regulators look for those marks.

Certified components also improve market acceptance. Articles from Unex, C3 Controls, and others point out that certified products tend to stand out with buyers, inspectors, and insurers. For many retailers and industrial customers, using certified control equipment is a de facto requirement. In some energy and safety markets, certifications such as UL 9540 or EN 54 series compliance are explicit tender conditions, without which a bid is simply non-responsive.

On the downside, certification programs introduce cost and schedule pressure. UL’s processes are widely respected but often more demanding and time-consuming than alternatives, as highlighted by comparisons between UL and other labs. CE conformity assessment, even when based on self-declaration, still requires engineering time for testing, documentation, and risk analysis. For smaller projects, or for prototype deployments, it is tempting to bypass certification requirements and rely on informal assurances instead.

In my experience, that temptation rarely pays off.

The cost of rework after a failed inspection or a denied insurance claim almost always dwarfs the upfront expense of using certified components and following a clear compliance plan.

Common Misconceptions That Derail Projects

Several recurring misconceptions cause trouble in global control projects, and they are worth calling out explicitly.

The first is the belief that CE and UL are interchangeable. Multiple sources, including 4C Consulting and industry case studies, make it clear that CE is about EU market access while UL is about safety certification that satisfies North American codes and insurers. A CE-marked device may still be unacceptable to a U.S. AHJ if it lacks an NRTL mark. Conversely, a UL Listed panel without CE marking may not be legally sold or installed in Europe.

The second misconception is that any piece of paper that says “CE certificate” is sufficient. European Commission guidance warns about so-called voluntary certificates that are not based on the legally prescribed conformity assessment procedures and may even be issued without proper testing. For serious projects, certificates should be backed by real test reports, legitimate Notified Bodies when required, and a traceable technical file.

The third misconception is that using UL Recognized components automatically makes the final panel UL Listed. Guidance from UL and UL 508A-certified manufacturers is clear: component recognition simplifies panel listing, but it does not replace it. The panel shop still has to follow UL 508A, select compatible components, calculate ratings such as SCCR, and maintain documentation. Only then can they legitimately apply the UL mark to finished panels.

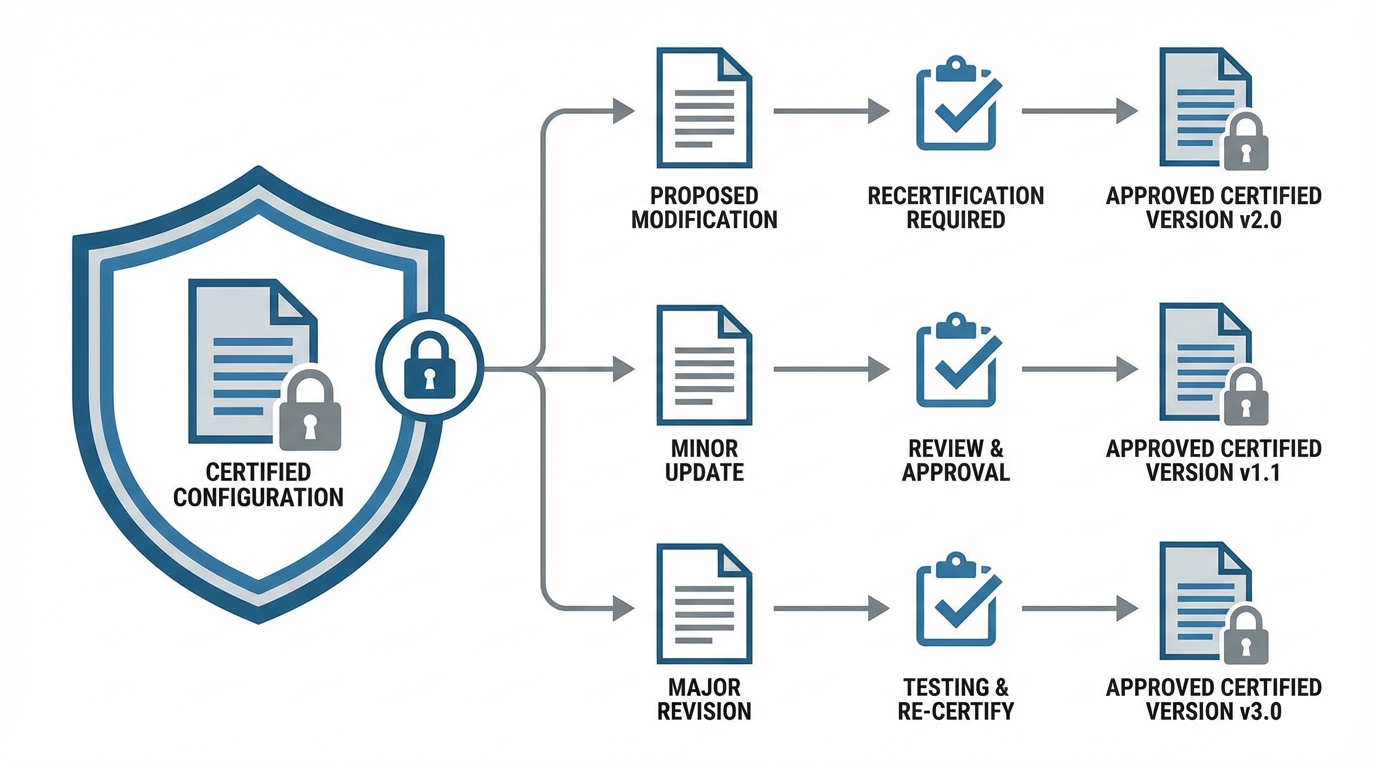

A subtle but important fourth misconception is that once a product is certified, it stays certified forever. CE-related guidance notes that the Declaration of Conformity and technical documentation must be kept up to date and that significant design changes or regulatory updates may require reevaluation. UL sources likewise emphasize that design changes can trigger fresh testing and that follow-up inspections monitor continued compliance. For integrators, this means treating certified designs as controlled configurations, not as endlessly mutable templates.

Verifying Marks And Guarding Against Counterfeits

Given the prevalence of fake marks and misleading claims, verification is part of any serious compliance program. CE-focused compliance resources recommend authenticating CE certificates using official databases or contacting issuing authorities directly. If a product is not registered where it should be, or if the certificate scope does not match the device, that is a red flag.

UL and other NRTLs maintain publicly accessible databases where you can look up certification numbers, file references, and product categories. Industry advice from energy storage and industrial PC suppliers is consistent: do not just trust a logo in a catalog. Instead, check the manufacturer’s datasheet, the physical mark on the component, and the listing in the relevant database. If anything does not line up, raise the question before you approve the BOM.

In control projects, this verification duty often falls to whoever owns the panel design. On multi-site or multinational projects, I recommend building a simple internal checklist: confirm that each critical control component has verifiable UL, CE, or equivalent certification appropriate to the markets, and store those confirmations in the project’s design record.

Dual And Multi-Standard Strategies For Global Platforms

Energy and renewables examples from Gletscher Energy and Jensen Hughes illustrate where the control world is heading. Serious products are increasingly built around dual or multi-standard certification. A battery energy storage system may be CE-marked under the EU Battery Regulation, listed to UL 9540 for North American installations, and tested to IEC standards for batteries and inverters. Similarly, a sophisticated solar inverter or industrial edge computer might be both UL certified and CE-marked and evaluated to IEC safety and EMC standards.

For control hardware, a pragmatic strategy looks similar. Choose components and suppliers that can show alignment with UL, CE, and IEC norms. Design panels around UL 508A for North American deployments while ensuring that the components, safety functions, and documentation also satisfy EU directives and EN standards. Consider optional marks such as the UL-EU mark when you want an extra layer of independent validation for European stakeholders.

The payoff is flexibility. When your core control platform is built on components that already satisfy the main global schemes, adapting it for a new geography becomes a documentation and labeling exercise, not a ground-up redesign.

FAQ: Practical Questions From The Field

What is the real difference between UL Listed and UL Recognized for control components?

UL Listed applies to a complete, stand-alone product that has been evaluated for safety as an assembly in its intended use. Think of a finished industrial PC, a complete power supply in its enclosure, or an industrial control panel. UL Recognized applies to components and subassemblies intended to be built into larger equipment, such as bare boards, internal power modules, or I/O cards. Recognized components simplify the certification of the final product, but they do not, by themselves, create a certified end device. A control panel built entirely from UL Recognized components still needs its own evaluation, typically to UL 508A, before it can legitimately carry a UL mark.

If my components are CE-marked, do I still need UL for North America?

For most industrial projects in the U.S. and Canada, the short answer is yes. CE marking is a legal requirement for access to EU markets and indicates that the manufacturer has declared conformity with EU directives. It does not serve as a recognized safety certification under North American electrical codes. AHJs and insurers commonly look for marks from UL or other Nationally Recognized Testing Laboratories on panels, fire alarm systems, energy storage products, and other control hardware. CE components may still be part of a North American design, especially if they also meet IEC standards, but a CE logo alone rarely satisfies North American inspectors.

When do I actually need a Notified Body for CE on control equipment?

European guidance explains that CE marking is usually based on manufacturer self-assessment when harmonized standards are followed, but certain higher-risk products require a Notified Body to perform part of the conformity assessment. Examples include some categories of machinery, pressure equipment, and specialized devices such as medical equipment. Many routine control components and panels can be self-declared if the manufacturer applies the relevant EN and IEC standards correctly and compiles a robust technical file. However, when in doubt, especially for complex machines or systems with significant safety functions, it is wise to consult a Notified Body or specialized compliance partner early in the design.

Closing Thoughts From A Project Partner

In industrial automation, UL and CE certified control components are not a nice-to-have; they are the backbone of systems that pass inspection, win approvals, and keep people safe. The integrators and OEMs who succeed across regions are the ones who treat certification as a design input, not a postscript, and who choose components and partners that can stand up to scrutiny from AHJs, insurers, and regulators. If you build your next control project around verifiable UL and CE compliance from the component level up, the commissioning phase becomes a conversation about performance and throughput, not about missing logos on a nameplate.

References

- https://do-server1.sfs.uwm.edu/exe/341918P2P9/chap/50413PP/nec_article_409-and_ul-508a_4__siemens.pdf

- https://www.procurement.vt.edu/content/dam/procurement_vt_edu/procedures/field-evaluation-services-brochure.pdf

- https://blog.unex.net/en/blog/unex/the-importance-of-certifications-in-the-electrical-sector

- https://multi-craft.net/2023/11/09/the-importance-of-ul-certification-for-control-panels/

- https://360compliance.co/safety-ul-std-certification/

- https://aerosusa.com/everything-to-know-about-becoming-ul-listed-or-certified/

- https://www.c3controls.com/white-paper/difference-between-ul-recognized-ul-listed?srsltid=AfmBOorqwLPB9r4cXwaGWiBsekh5le2sqBoFVfMMHMazOy0JElqKcyfy

- https://www.coolgear.com/guides-informative-articles/the-importance-of-compliance-certifications-ensuring-product-safety-performance.html

- https://innxeon.com/ul-vs-ce-certifications-for-fire-alarm-systems-what-consultants-should-recommend/?srsltid=AfmBOoq43I_P-CAUYYIO0h7wKn6eFgB5py7p_1VoUEOWeNz7dTWbLLxw

- https://www.jensenhughes.com/insights/ce-marking-vs-ul-9540-understanding-global-safety-and-compliance-for-bess

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment