-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

Consignment Inventory Programs for Automation Components: A Field-Tested Guide

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

When a production line is down because of one missing component, nobody in the plant cares whether the part is on your balance sheet or your supplier’s. They just want the line back up. As a systems integrator who has stood in that aisle with maintenance, purchasing, and a frustrated plant manager, I have seen consignment inventory programs either eliminate those emergencies or quietly die after a year of confusion and finger‑pointing.

Consignment can absolutely work for industrial automation and control hardware, but only when it is treated as an engineered system, not a handshake deal. Research from industrial supply chain literature and inventory software providers shows that well‑designed consignment stock can lower total supply chain cost, improve availability, and reduce working capital for the plant. Poorly designed programs, on the other hand, simply move cost and risk from one spreadsheet to another without fixing availability or data problems.

This article walks through how consignment inventory programs actually work for automation components, what the research says about their economics, and how to design a program you can trust in a real plant environment.

What Consignment Inventory Really Is in an Automation Context

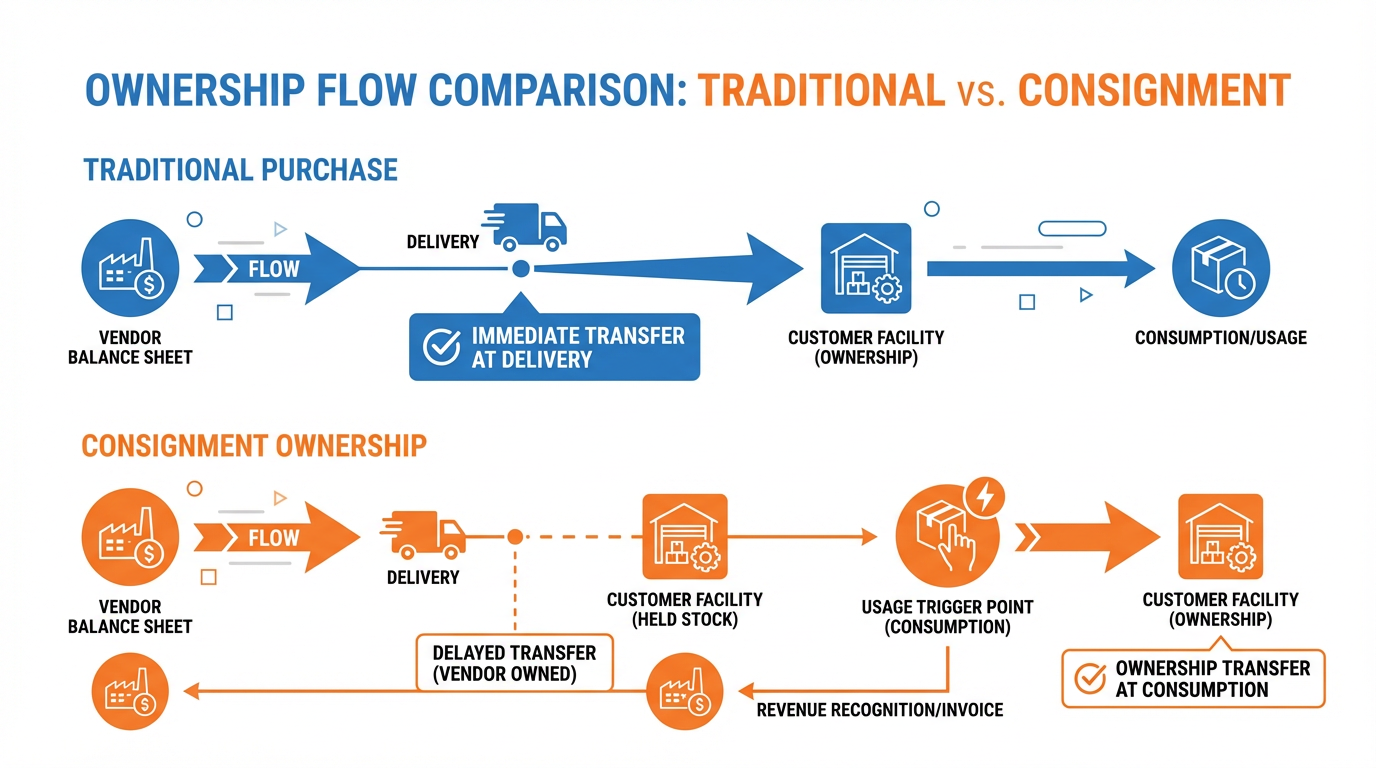

In a consignment inventory arrangement, your supplier places goods at your location, but ownership stays with the supplier until you use the items. Accounting guides such as those from Finale Inventory and NetSuite are consistent on this point: consigned goods remain on the consignor’s balance sheet as inventory, while the plant (the consignee) treats them as off‑balance‑sheet stock and records a liability only when parts are consumed or sold.

Industrial engineering literature calls the specific case where stock sits physically inside the buyer’s plant but remains vendor‑owned “Consignment Stock.” A methodological framework published in the International Journal of Production Research describes this as a collaborative policy that intentionally splits the holding cost into two pieces. The buyer carries the physical and handling component in their facility, while the vendor carries the financial cost of capital tied in stock until consumption.

Practically, for automation components, that usually means bins, cabinets, or a cage on your site that contain vendor‑owned drives, safety relays, IO modules, connectors, and similar items. Maintenance teams pull from those bins as needed. The supplier only invoices what you actually used, often in batched periods such as weekly or monthly, rather than every time a technician grabs a part.

Consignment is not the same as simple vendor‑managed inventory. In vendor‑managed inventory, the supplier may plan and replenish your stock but you still own it. In consignment, the supplier both manages and owns the stock until the last step, when control truly transfers to you or your customer.

How a Program Operates Day to Day

Although each implementation looks a little different, the flow is consistent with descriptions from accounting and retail‑consignment sources such as Shopify, Lightspeed, and Finale Inventory.

First, the parties agree on terms and items. A written consignment agreement defines which SKUs are eligible, what minimum and maximum levels apply, how often stock will be reviewed, how prices and commissions are handled, and who carries risk for damage or shrinkage.

Second, the supplier ships and stages the inventory. Items are delivered to your plant or warehouse and stored in clearly identified consignment locations. The supplier reclassifies those items in their records into an “inventory on consignment” category rather than regular warehouse stock, as described in accounting examples. You track them in your inventory or maintenance system, but they are flagged as vendor‑owned.

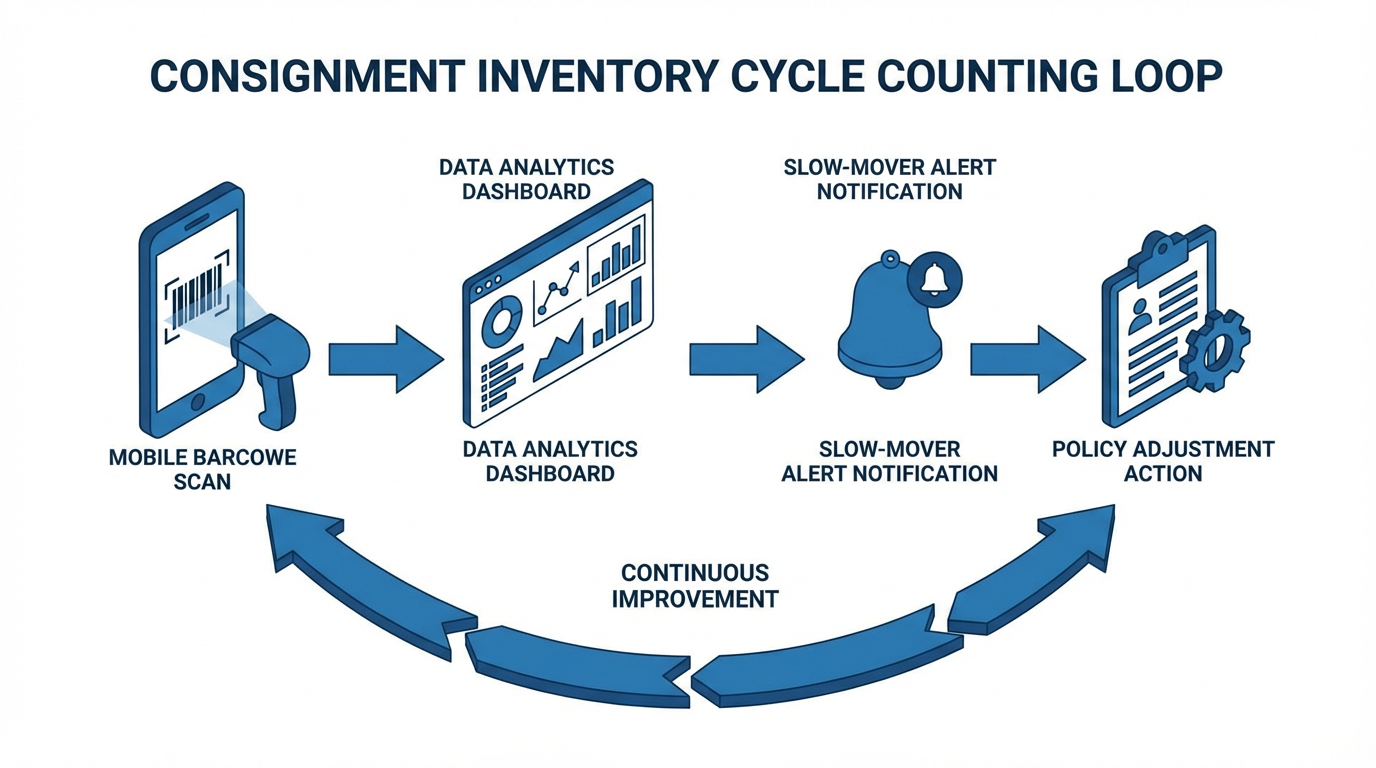

Third, your operations consume parts. When a technician pulls a consigned sensor or module, that consumption must be recorded. Modern consignment systems and ERP‑integrated mobile tools—highlighted in best‑practice guides from RFgen, eTurns, and consignment software vendors—capture this at the point of use using barcode or RFID scanning. In smaller programs, technicians may scan at a cabinet or log usage into a handheld device that syncs later.

Fourth, the supplier bills based on actual usage. Instead of issuing countless small purchase orders, mature programs consolidate usage into periodic invoices. The eTurns TrackStock guidance warns clearly against trying to manage consignment with tools that generate a flood of tiny invoices. Batched billing using usage data reduces admin overhead for both sides.

Finally, the parties deal with slow movers and obsolete stock. Contracts and best‑practice articles from Cleverence, Fishbowl, and NetSuite emphasize the need for explicit rules for unsold or unused items: return, markdown, or buy‑out after a defined period. In retail consignment, three to six months and trial periods of around ninety days are common examples. In automation, that timing should be tied to demand patterns and obsolescence risk, not just the calendar, but the principle is the same: stock that never moves needs a defined exit path.

Why Plants and Suppliers Bother: The Real Benefits

The appeal of consignment inventory for automation components is simple: it promises plant‑level availability without tying up plant‑level cash. Various guides from NetSuite, Shopify, Lightspeed, and consignment specialists outline consistent advantages.

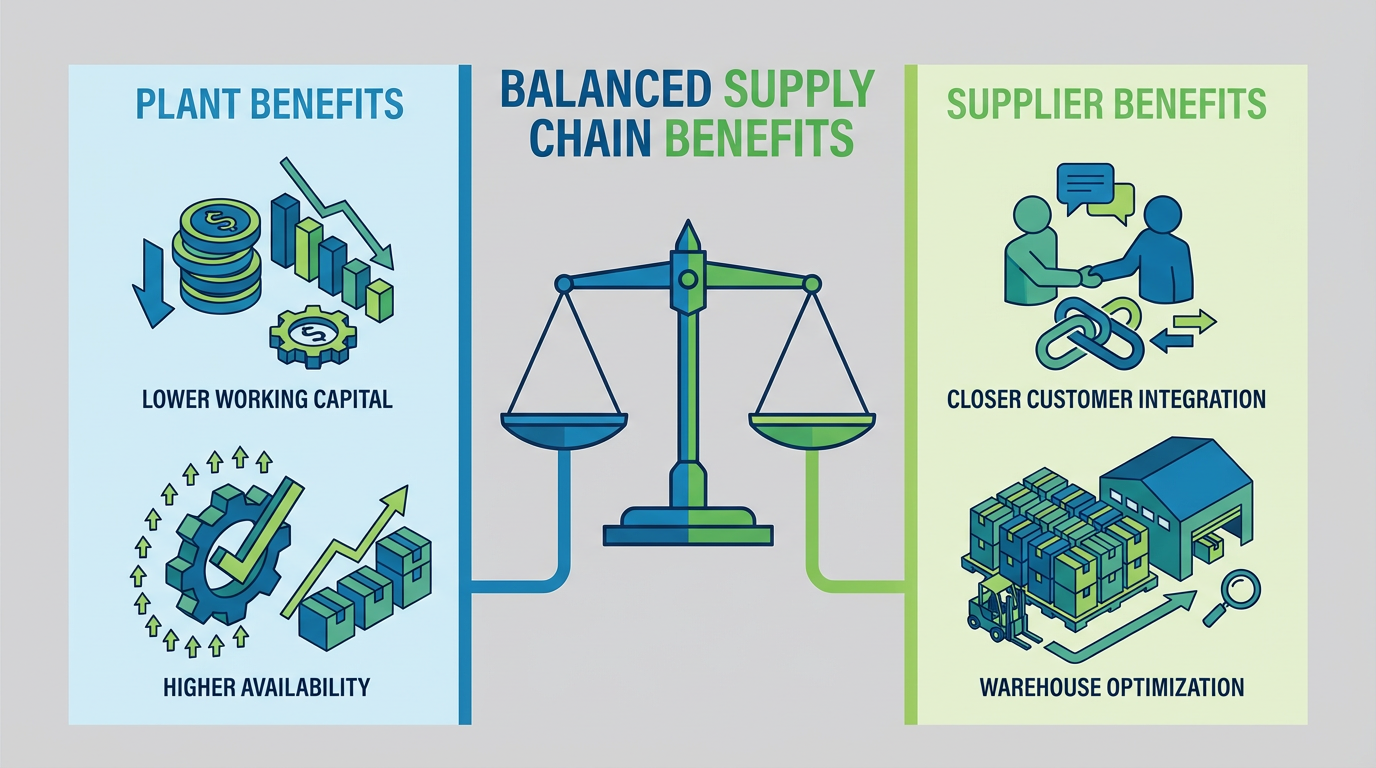

From the plant’s perspective, cash flow improves because there is no upfront purchase. You pay only when a part is used, which frees capital for projects, staffing, or other investments. Retail and accounting sources stress that consignment expands assortment with lower financial risk, and that applies very directly to automation spares where maintenance wants coverage for rare but critical failures that purchasing cannot justify buying outright.

Operations can also gain reliability. Research on consignment stock policies in industrial settings shows that, for standard consumable components, total annual supply chain costs under traditional Economic Order Quantity policies are always higher than under a well‑designed consignment approach, even when demand is volatile and warehouse space is constrained. The buyer benefits from reduced financial holding cost, elimination of purchase‑order handling for every replenishment, and better assurance of material availability with lower stock‑out risk.

From the supplier’s side, articles from eTurns and other consignment software providers describe a different but compelling benefit set. Consignment programs deepen customer relationships and make the distributor part of the customer’s day‑to‑day operations. They enable market penetration and brand visibility without opening new branches. By pushing inventory physically closer to consumption, suppliers can also reduce the stock they carry in their own central facilities, freeing warehouse capacity for other items and increasing production and delivery flexibility, as the industrial research paper notes.

There is also a strong data angle. Final accounting and inventory guides and RFgen’s best‑practice material emphasize that consignment, when integrated with ERP and mobile data collection, yields cleaner consumption data at the point of use. That data flows back into forecasting, product development, and pricing decisions much faster than periodic bulk orders ever could.

A simplified view of how the two sides benefit is shown below.

| Perspective | Operational effect | Financial effect |

|---|---|---|

| Plant / end customer | Higher availability at point of use; fewer stockouts | Less working capital tied in inventory; PO workload reduced |

| Distributor / supplier | Closer integration with customer operations | More inventory on customer site, less in own warehouse; new revenue opportunities |

This picture, however, only holds if you address the risks explicitly.

The Tradeoffs and Risks You Must Design Around

Every benefit has a mirror‑image risk. Industry articles from NetSuite, Lightspeed, eTurns, Shopify, and Cleverence repeat the same warning: consignment is powerful, but it magnifies any weaknesses in process or trust.

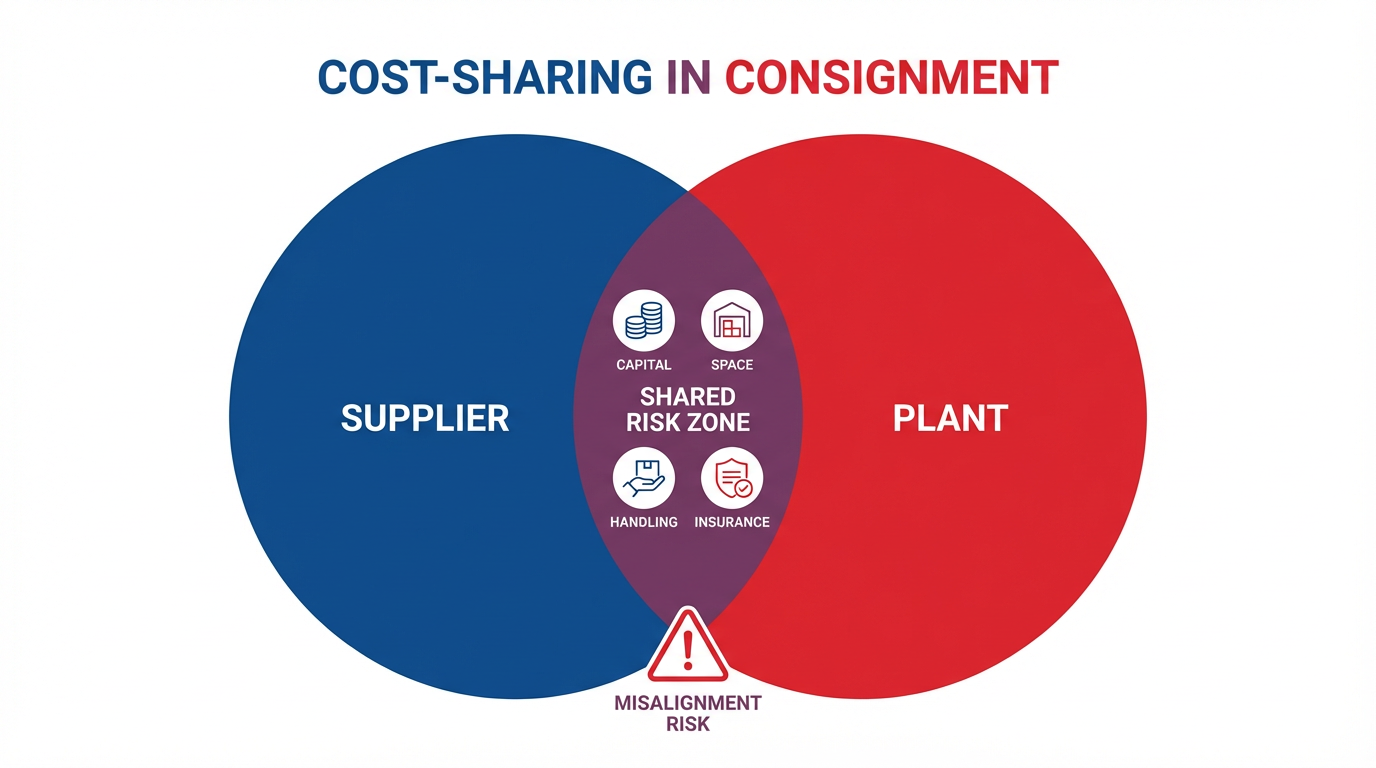

For suppliers, the main tradeoff is working capital and risk exposure. They finance inventory sitting on customer floors with no guarantee of sell‑through. Cash flow becomes less predictable because revenue only appears when the customer uses parts and when the parties settle invoices. They also carry more risk from obsolete or damaged goods since ownership remains with them until consumption. Several sources note that consignors often accept lower profit margins than outright sales once extra handling, packaging, shipping, and shrinkage are factored in.

For plants, consignment is not free either. They must dedicate storage space, handling effort, and process discipline to stock they do not own. Retail‑oriented sources such as Lightspeed and Shopify point out that retailers may be liable for damaged or stolen consigned goods, which translates directly to liability exposure for a plant holding high‑value automation hardware. Plants also face the complexity of separate inventory processes; staff must be trained to distinguish consigned from owned stock, and systems must be able to report on both.

There is an economics trap here as well. eTurns warns distributors not to focus only on gross sales. Carrying costs for inventory, according to that guidance, can run in the range of roughly twenty‑five to fifty‑five percent of inventory value per year once capital cost, space, insurance, and handling are included. Consignment shifts much of that cost from the plant to the supplier, but it does not make it disappear. If both parties do not understand and share those economics, friction is inevitable.

The conclusion from both research and practice is straightforward. Consignment inventory can reduce total supply chain cost and improve availability, but only when both parties are honest about the risks and design the program explicitly to handle them.

Choosing the Right Automation Components for Consignment

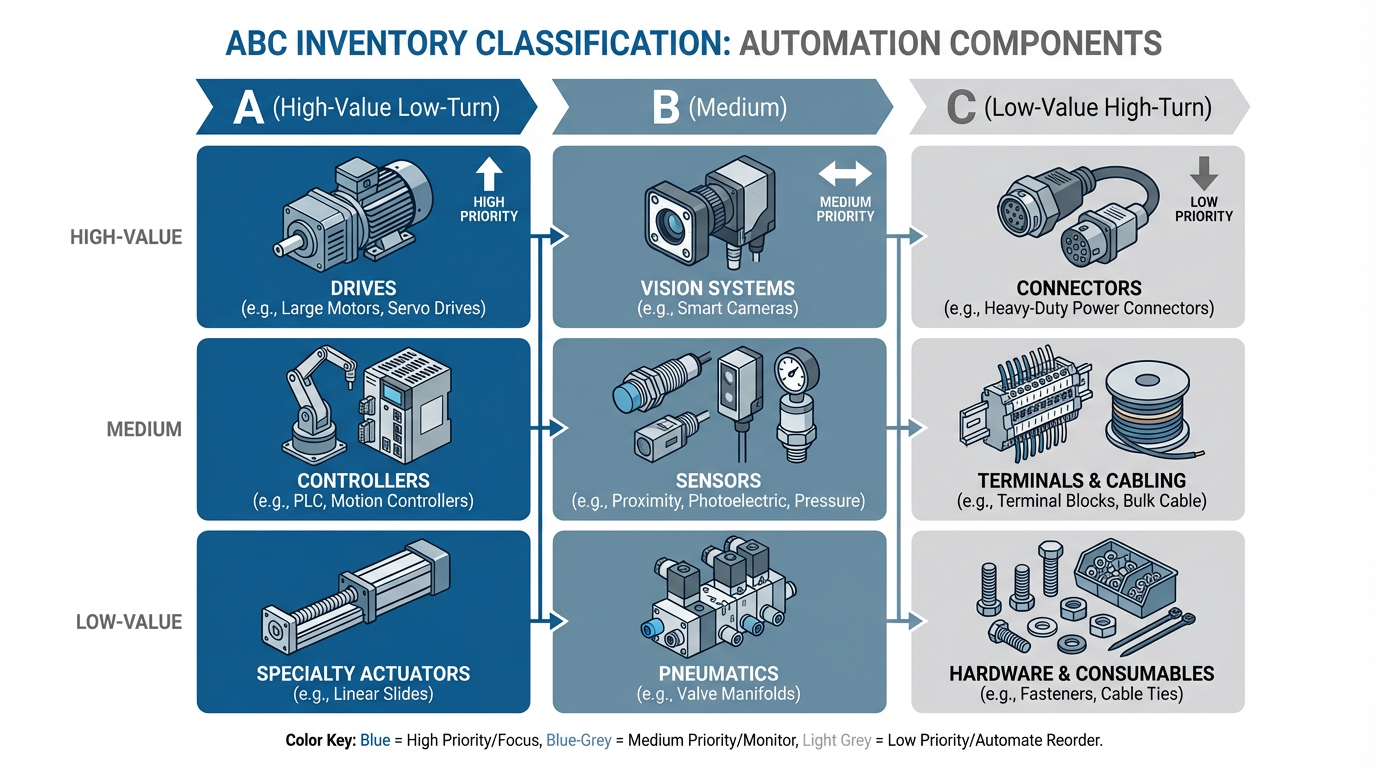

Not every automation part belongs in a consignment program. The academic work on consignment stock in industrial environments recommends targeting items with high annual consumption, small physical size, variable demand, and a real risk of obsolescence. Examples given include fasteners, small parts, tools, packaging, and personal protective equipment. In automation, many standard control and panel components behave similarly from an inventory perspective, even if they are more expensive than simple fasteners.

Other guidance, such as Temperform’s summary of consignment practice, emphasizes higher‑value, slower‑moving, or specialized items where retailers hesitate to buy outright. eTurns adds a further nuance: focus consignment on fast‑turning, higher‑value items where the business case is clearly strong and resist the urge to put everything on consignment. Taken together, the signal is that you should apply consignment where shared risk and better availability produce a clear win, not as a blanket policy across the catalog.

Inventory strategy frameworks like those described by Netstock and EOX recommend starting with basic classification. Using ABC analysis, “A” items are high‑value and often lower‑turn, “C” items are low‑value and higher‑turn. Consignment can make sense for both ends of that spectrum, but for different reasons. High‑value items may be consigned because plant purchasing does not want to tie up capital, while high‑turn items are attractive because they justify the supplier’s investment through rapid, predictable consumption.

A pragmatic approach in automation environments is to start with a small, clearly defined segment of standard consumable components that align with these profiles and expand only once the data shows healthy turns and acceptable margins.

Engineering the Inventory Policy: Min/Max and Safety Stock

Once you know which components to include, the next challenge is sizing the consignment stock and controlling replenishment. Several sources converge on using minimum and maximum levels, backed by analytics.

The industrial consignment stock model in the International Journal of Production Research decomposes the holding cost into financial and physical elements and then solves for an optimal delivery quantity that minimizes combined annual cost for both vendor and buyer, subject to service‑level and warehouse‑space constraints. A key operational parameter in that work is a minimum stock level, often described as a safety stock, which protects against demand variability and lead‑time uncertainty.

In a documented implementation at Philips Taiwan, that minimum stock was set using a “fluctuation index,” defined as the ratio of demand standard deviation to the forecast consumption rate. Higher variability pushed the minimum stock higher. This is a more rigorous alternative to simple rules of thumb and offers a blueprint for automation distributors and plants that have enough history to compute such metrics.

Commercial tools such as eTurns TrackStock add another layer by calculating optimal minimum and maximum levels based on actual usage data and then exposing those recommendations through dashboards. Their material notes that the system’s automatic replenishment can help distributors invest the minimum necessary cash in consigned inventory while still meeting customer service levels, and they report that replenishing inventory via such a system can be roughly ten times faster than using generic e‑commerce sites or paper-based methods, with same‑customer revenue increases of over thirty percent in some cases.

The key point is that consignment policy should be driven by data: historical usage, demand variability, lead times, and service‑level targets. Tools and models exist to do that work; ignoring them and choosing levels purely by gut feel simply pushes risk around rather than reducing it.

Systems and Data: The Backbone of a Viable Program

Consignment inventory lives or dies on accurate, shared visibility. Almost every best‑practice source, from RFgen and NetSuite to consignment‑software vendors and inventory‑tracking guides, stresses ERP integration and real‑time or near‑real‑time data collection.

RFgen’s comprehensive guide to tracking consignment explains that ERP integration should consolidate data from multiple systems, auto‑update the central source of truth when transactions occur elsewhere, and minimize manual data entry. Mobile data collection is highlighted as especially important: barcode scanners or mobile devices let technicians perform cycle counts, record consumption, and update item status at the point of activity. Offline capabilities matter as well since many industrial sites have weak connectivity; mobile tools need to store data locally and synchronize when connections return.

Inventory tracking research for consignment shops shows a progression from paper to spreadsheets to specialized consignment software, then to barcode, RFID, and fully integrated platforms. For small operations with only a few hundred items, spreadsheets might work if they are rigorously maintained. As item counts and locations grow, consignment software that automates updates and payouts becomes necessary. At larger scale, integrated systems that combine inventory, accounting, customer management, and multi‑location support (for example, ERP suites similar to NetSuite) are the norm. Typical costs cited for such integrated systems are on the order of about $99.00 to $1,500.00 per user per month, with some enterprise solutions reaching $2,000.00 or more per user per month.

These costs are not trivial, but studies referenced in inventory software articles indicate that businesses using integrated systems experience around twenty‑five percent lower inventory costs and thirty percent better order‑fulfillment rates, with roughly seventy‑one percent reporting improved inventory accuracy. For high‑value automation hardware and the cost of downtime, those improvements often justify the investment.

The message for automation consignment is clear. Whatever tools you choose, they must support barcoding or similar item identification, integrate tightly with the core ERP or maintenance system, and provide real‑time or near‑real‑time visibility of consigned stock at every location.

Operating the Program: Receiving, Labeling, and Replenishment

Inventory best‑practice material from Circular, Cleverence, and SimpleConsign all emphasize that thrift and consignment operations succeed when intake and labeling are disciplined. The same pattern holds in automation.

Every consigned item should receive a unique identifier linked to your inventory or maintenance system and to the supplier’s records. Labels need to carry, at a minimum, that identifier and a clear description; in some environments they also include price or standard cost, and in regulated sectors lot or serial numbers for traceability, as recommended in Finale’s accounting guidance. Consignment articles aimed at thrift and consignment stores stress categorizing items by attributes such as category, brand, and size to support search and analytics. In automation, categorize by functional area, voltage class, system, or another scheme that aligns with how technicians actually search for parts.

Real‑time tracking of consignment inventory is a recurring theme in sources such as Cloud‑in‑Hand’s consignment optimization guide and Circular’s inventory management best practices. Manual methods are singled out as a root cause of misplaced stock and disputes between partners. Automating replenishment based on real‑time consumption data keeps stock at agreed levels and prevents both stockouts and overstocking, while configurable reorder points and automated notifications streamline communication between plant and supplier.

For ongoing control, several articles recommend regular cycle counts rather than infrequent full inventories. Ventory’s discussion of mobile cycle counting for consignment overstock explains that small, frequent counts with mobile devices and barcode scanning are more accurate and less disruptive than yearly shutdown counts. The data from those counts feeds analytics that highlight slow movers and discrepancies, which in turn drive adjustments to stock levels and policies.

Governance, Contracts, and Communication

Across multiple sources—from Cleverence and Fishbowl to Shopify, NetSuite, Finale, and eTurns—the same governance pattern appears: detailed contracts, regular communication, and auditable data.

A strong consignment agreement should spell out ownership and risk of loss at each step, payment terms and cadence, how pricing and discounts work, how long items will remain on consignment, how unsold or obsolete stock is handled, which party insures the goods, and how disputes will be resolved. Legal and accounting guides emphasize the importance of defining when “control” transfers for revenue recognition, pointing to standards such as ASC 606 and IFRS 15; while the detailed accounting may sit with finance, the operational contract must align with those triggers.

Operational best practices from Cleverence and NetSuite recommend regular stock reviews—weekly or bi‑weekly for higher‑volume items, slower for low‑volume parts—combined with joint performance reviews. Those reviews should look at turnover, stockouts, shrinkage, and profitability, not just sales volume.

Communication is another recurring theme. Cleverence stresses two‑way communication, with suppliers sharing forecasts, promotions, and launches, while retailers or customers share sales data and qualitative feedback. eTurns recommends that distributors ask tough questions before setting up consignment: where and how inventory will be stored, who has access, what happens if it does not move, and how losses will be handled. Without these conversations upfront, even well‑designed systems cannot overcome misaligned expectations.

In high‑stakes environments such as medical device consignment, MoveMedical highlights the need for cross‑functional collaboration between sales, supply chain, finance, and provider partners, coordinated via a unified platform. Automation consignment is not as tightly regulated as healthcare, but the same principle applies. Without alignment between maintenance, engineering, purchasing, finance, and the supplier’s account team, the program will drift.

Common Failure Modes in Automation Consignment

Having watched consignment programs succeed and fail around automation components, the failure patterns I see mirror the risks described in the research and vendor literature.

One frequent failure is implementing consignment without a real contract. Articles from Fishbowl, Cleverence, and Shopify all warn that vague agreements lead directly to conflict over ownership, damage, and payment. In automation, that usually surfaces the first time there is a major stock discrepancy or a high‑value module goes missing.

Another is agreeing to whatever the customer wants, as eTurns bluntly cautions suppliers against. When distributors set up consignment in unsecured areas, accept unlimited returns of unsold items, or tolerate customers using consigned stock as a general warehouse without usage tracking, the economics rarely work. Plants can fall into a similar trap if they accept systems that do not integrate with their existing ERP or maintenance tools and then end up with double entry and confusion.

A third failure mode is managing consignment manually for too long. Multiple sources explain that paper logs and simple spreadsheets might work for very small shops, but as item counts and locations grow, they become error‑prone and impossible to keep up to date. This is especially dangerous when consigned and owned stock are mixed in the same racks without clear labeling and system support.

Blind trust without verification is another recurring issue. Shopify’s consignment guide points out that suppliers who fail to audit store sales records against their own often discover unreported sales or inaccurate counts much later. In the industrial context, that translates to unrecognized consumption, disputed invoices, and strained relationships. Consignment inventory, by definition, moves risk to the supplier; that makes audit trails and cycle counts non‑negotiable.

Finally, many programs fail because neither side runs the numbers on net margin. eTurns and Finale both stress that consignment has additional costs: handling, extra shipping, software, audits, and carrying cost. If these are ignored, distributors may discover that what looked like a great revenue stream is barely covering cost, and plants may find that the effort to manage consignment yields only small gains over simply buying and holding a modest safety stock.

When Consignment Inventory Is Not the Right Tool

Consignment is a powerful tool in the inventory‑strategy toolbox described by Netstock and others, but it is not universal. It is a poor fit when the supplier cannot absorb the working‑capital impact, when items are highly customized or project‑specific, or when there is little trust or transparency between parties.

In some cases, traditional purchasing with well‑designed reorder points and safety stock provides all the availability the plant needs at lower complexity. In others, vendor‑managed inventory without transfer of ownership can capture many of the replenishment and forecasting benefits without shifting legal ownership. The right answer depends on the specific item profiles, the financial constraints of each party, and the maturity of their systems.

The good news is that consignment programs can be piloted. Several sources suggest starting with limited assortments, shorter periods, and a few locations, then expanding only when the data shows healthy turnover, clean reconciliation, and acceptable margins.

Short FAQ

How is consignment inventory different from vendor-managed inventory for automation components?

In consignment inventory, the supplier owns the stock sitting in your plant until you consume it. In vendor‑managed inventory, the supplier plans and replenishes your inventory, but you may own the stock as soon as it arrives. NetSuite’s and Finale’s accounting guidance emphasize that in consignment, consigned goods stay on the supplier’s balance sheet until a defined control‑transfer event, such as usage or sale, while in vendor‑managed inventory they often sit on the customer’s books even though the supplier is making the replenishment decisions.

Who should own the system used to track consigned automation parts?

Best‑practice material from RFgen, Finale, and consignment‑software providers points toward a shared data environment anchored in the customer’s ERP or maintenance system, with supplier visibility into the relevant data. The critical requirement is that all consumption and movement transactions end up in a single source of truth that integrates with accounting. Whether the primary application license sits with the plant or the supplier matters less than ensuring barcodes or RFID are used consistently, mobile tools are practical for technicians, and both parties can see the same accurate numbers.

How do we start a consignment program without taking on too much risk?

Guides from Temperform, Shopify, and eTurns all recommend starting small. Define a narrow set of components that are strong candidates based on consumption and value, choose one or two locations, and set a clear initial term, such as around ninety days, with explicit review milestones. During that period, track usage, stockouts, shrinkage, and margin carefully. At the end of the trial, use that data to adjust minimum and maximum levels, refine the contract, or even decide not to continue. A disciplined pilot is far safer than trying to roll out consignment across every critical spare in the plant at once.

Closing Thoughts

A consignment program for automation components is not just a finance trick; it is a control system for material flow between you and your supplier. When it is designed with solid analytics, robust systems, and clear contracts, it can support uptime, free capital, and deepen partnerships. When it is bolted on as an afterthought, it simply hides risk until the worst possible moment. The plants and suppliers I see winning with consignment treat it like any other critical system: they engineer it, instrument it, and keep tuning it over time.

References

- https://www.academia.edu/95870201/Consignment_stock_inventory_policy_methodological_framework_and_model

- https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=15184&context=dissertations

- https://old.ntinow.edu/libweb/WhWjJw/3S9058/how__to-start-consignment-business.pdf

- https://admisiones.unicah.edu/book-search/WhWjJw/3OK058/how-to__start_consignment__business.pdf

- https://movemedical.com/10-game-changing-best-practices-for-managing-medical-device-consignment-inventory

- https://consignr.app/blog/multi-location-consignment-store-management-complete-guide

- https://www.finaleinventory.com/accounting-and-inventory-software/consignment-inventory-accounting

- https://www.fishbowlinventory.com/blog/what-you-need-to-know-about-consignment-inventory

- https://getcircular.ai/news/inventory-management-best-practices-for-thrift-and-consignment-stores

- https://www.shopify.com/blog/consignment-inventory

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment