-

Manufacturers

- ABB Advant OCS and Advant-800xA

- ABB Bailey

- ABB Drives

- ABB H&B Contronic

- ABB H&B Freelance 2000

- ABB Master

- ABB MOD 300, MOD 30ML & MODCELL

- ABB Procontic

- ABB Procontrol

- ABB Synpol D

- Allen-Bradley SLC 500

- Allen-Bradley PLC-5

- Allen-Bradley ControlLogix

- Allen-Bradley CompactLogix

- Allen-Bradley MicroLogix

- Allen-Bradley PanelView

- Allen-Bradley Kinetix Servo Drive

- Allen-Bradley PowerFlex

- Allen-Bradley Smart Speed Controllers

- 3300 System

- 3500 System

- 3300 XL 8mm Proximity Transducer

- 3300 XL NSV Proximity Transducer

- 990 and 991 Transmitter

- 31000 and 32000 Proximity Probe Housing Assemblie

- 21000, 24701, and 164818 ProbeHousing Assemblies

- 330500 and 330525 Piezo-Velocity Sensor

- 7200 Proximity Transducer Systems

- 177230 Seismic Transmitter

- TK-3 Proximity System

- GE 90-70 Series PLC

- GE PACSystems RX7i

- GE PACSystems RX3i

- GE QuickPanel

- GE VersaMax

- GE Genius I/O

- GE Mark VIe

- GE Series One

- GE Multilin

- 800 Series I/O

- Modicon 984

- Modicon Premium

- Modicon Micro

- Modicon Quantum

- Telemecanique TSX Compact

- Altivar Process

- Categories

- Service

- News

- Contact us

-

Please try to be as accurate as possible with your search.

-

We can quote you on 1000s of specialist parts, even if they are not listed on our website.

-

We can't find any results for “”.

-

-

Get Parts Quote

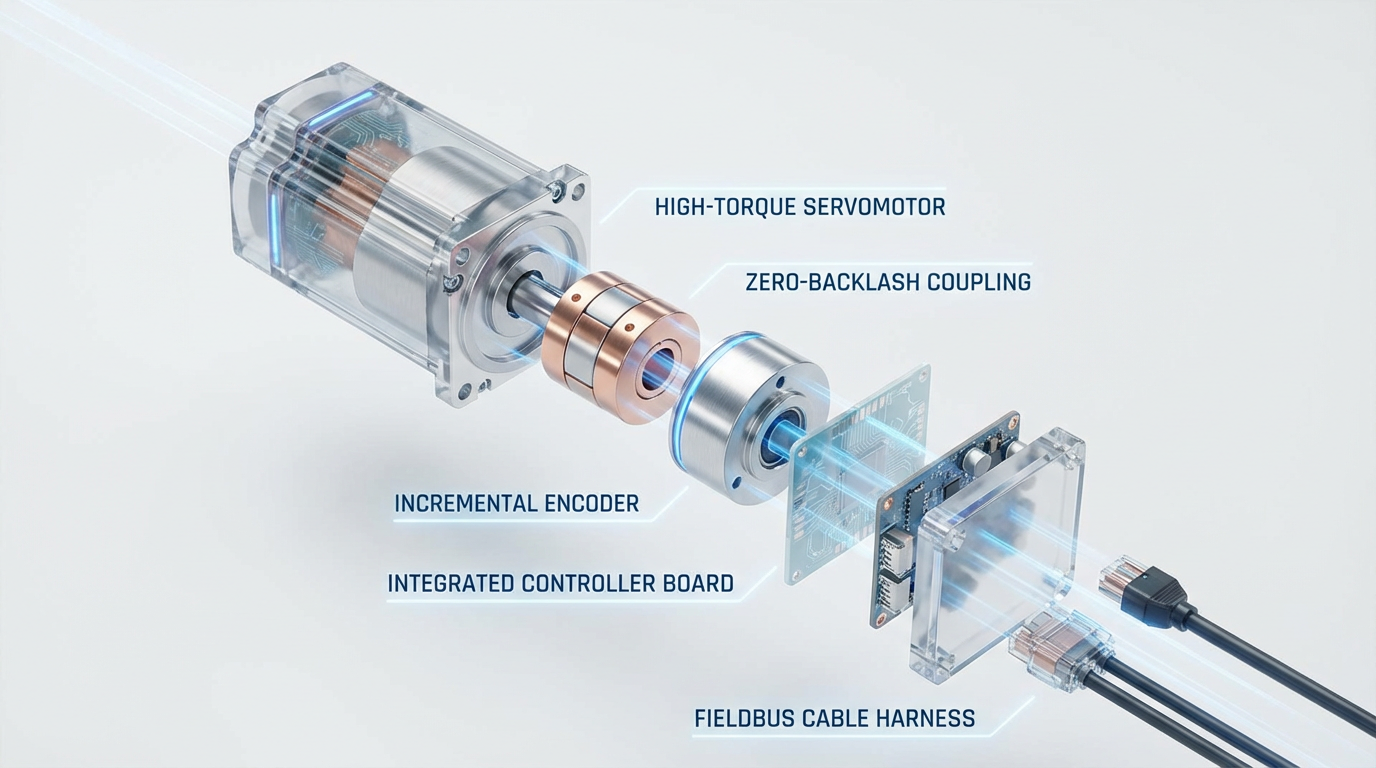

Position Control Modules with Nanometer Resolution Accuracy

This is my linkedin:

As a seasoned expert in the field of automation spare parts, Sandy has dedicated 15 years to Amikon, an industry-leading company, where she currently serves as Director. With profound product expertise and exceptional sales strategies, she has not only driven the company's continuous expansion in global markets but also established an extensive international client network.

Throughout Amikon's twenty-year journey, Sandy's sharp industry insights and outstanding leadership have made her a central force behind the company's global growth and sustained performance. Committed to delivering high-value solutions, she stands as a key figure bridging technology and markets while empowering industry progress.

Why Nanometer-Level Positioning Suddenly Matters

A decade ago, if a vendor claimed “nanometer resolution,” most plant engineers filed it mentally under marketing. Today, those claims are showing up in real specifications for semiconductor tools, medical devices, photonics, and advanced robotics. Industry groups such as the Association for Advancing Automation describe motion systems delivering sub‑nanometer positioning over several feet of travel to support single‑digit nanometer device geometries. Boston Engineering likewise highlights semiconductor robots working at nanometer‑level accuracy as a competitive differentiator, not a lab curiosity.

From the integrator side of the table, nanometer resolution is not about bragging rights. It is about yield, process capability, and long‑term reliability. If you are laser‑structuring medical implants, aligning photonic devices, or handling wafers, the difference between “micron‑class” positioning and true nanometer‑scale control shows up as scrap, rework, or missed acceptance tests.

The challenge is that “nanometer resolution” on a datasheet often describes what one component can resolve under ideal conditions. Precision motion, as the Automate motion‑control brief emphasizes, is a system‑level outcome. Accuracy, repeatability, minimum incremental motion, and in‑position stability all depend on how mechanics, actuators, sensors, electronics, software, and the environment interact. A position control module is only one piece of that puzzle—but it is the piece that has to coordinate all the others.

In this article I will walk through what “position control module with nanometer resolution accuracy” realistically means, how the technology works, where the real limits are, and how to specify and deploy these modules without betting your project on wishful thinking.

What A Position Control Module Actually Is

In industrial practice, “position control module” is used for several families of products:

A motion‑capable PLC or compact controller with dedicated position instructions. Maple Systems, for example, describes position control in its PLCs using a POSCTRL instruction that commands a stepper axis in real time without pre‑defined paths, including inching moves and on‑the‑fly speed changes. The controller, not separate drive hardware, is effectively your position module.

A smart axis controller meant to sit alongside or ahead of a PLC. W.E.ST. Elektronik offers positioning controllers for hydraulic axes that accept high‑resolution encoder signals, run PID‑style control with hydraulic‑specific features, and expose position, pressure, and status over fieldbuses like EtherCAT or Profinet. These modules encapsulate motion logic, leaving the PLC to orchestrate the cell.

A multi‑axis precision motion platform. Companies such as Aerotech, profiled by SAE Media Group, provide controllers that synchronize many axes using high‑performance communication buses and complex mathematical engines. These controllers are designed from the ground up for precision motion control rather than general automation.

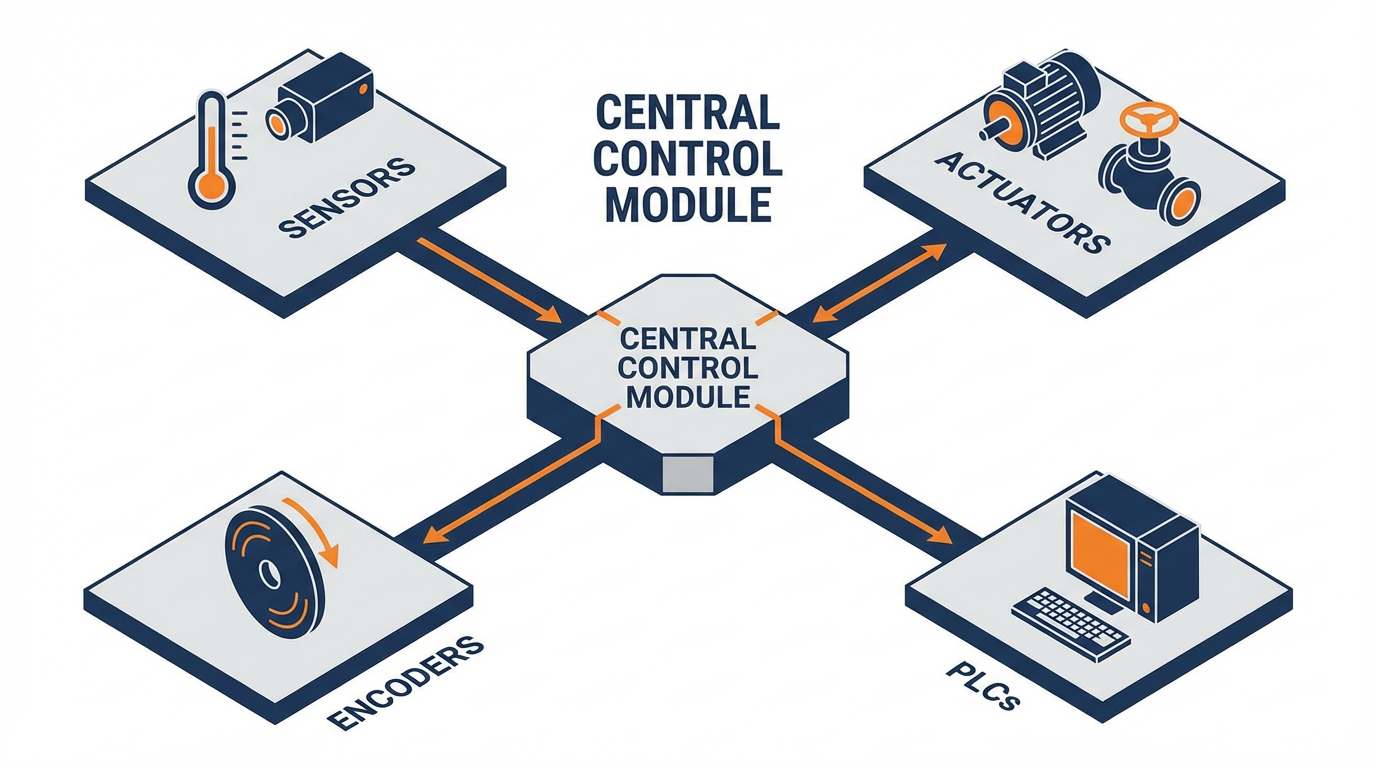

Regardless of packaging, a position control module has three non‑negotiable roles. It must accept a position command and generate a physically achievable trajectory. It must close one or more feedback loops using encoder or sensor data so the actual motion tracks that trajectory. And it must expose enough diagnostics, status, and interfaces for the rest of your automation stack to trust it.

A nanometer‑grade module simply pushes each of those roles to extremes. Commands may represent steps that are a tiny fraction of a microinch. Feedback devices need to provide many millions of counts per revolution or extremely fine linear resolution. Control loops must run with tight timing, high bandwidth, and excellent numerical precision. The mechanics and environment have to be designed to support that level of control, or the specs remain theoretical.

Core Building Blocks Of Nanometer-Grade Position Control

Feedback: Encoders And Position Sensors

Nanometer‑class performance starts with feedback. If you cannot reliably measure motion at that scale, you definitely cannot control it.

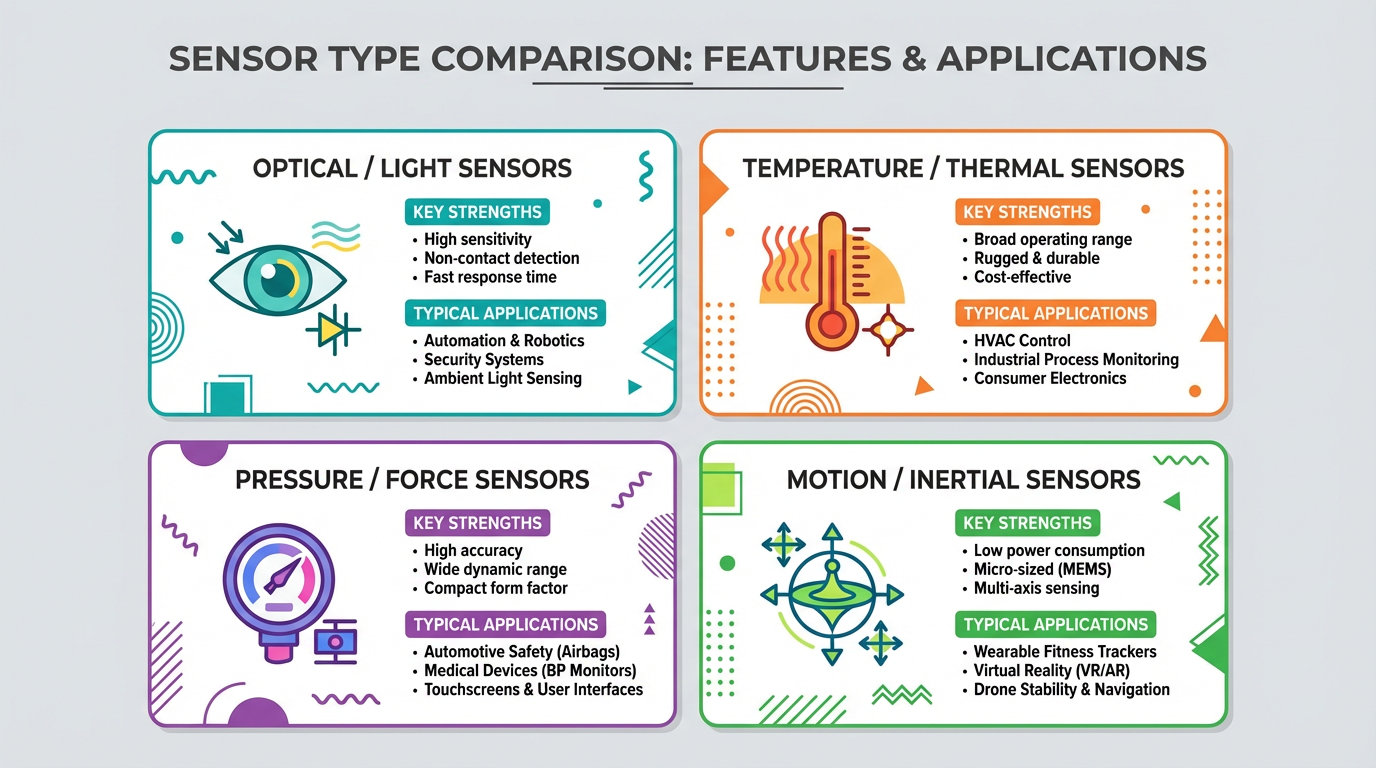

The position‑sensor literature is clear on how central sensing is. Technical articles on robotics position sensors describe them as the backbone of robotic applications, from industrial arms to MRI tables, because they tell the controller where everything actually is. Sensors fall broadly into linear, angular, and rotary families, with different trade‑offs depending on whether you are moving in a straight line, over a limited angle, or through continuous rotation.

Absolute position sensors, as described in robotics‑education resources, provide a unique position value at all times, not just changes from a reference. In anthropomorphic robots, absolute encoders in each joint let the controller know the exact posture immediately after power‑up, with no homing stroke. That is the sort of behavior you want in a serious position control module: the system knows where it is and can enforce safe motion the moment it comes online.

Magnetic encoders have become workhorses for nanometer‑scale systems. Arrow’s overview of magnetic encoders and position sensors points out that modern absolute magnetic encoders reach 14‑ to 18‑bit resolution, with contactless measurement, high immunity to dust and oil, and robust angular and linear sensing. Devices such as Melexis Triaxis‑based encoders can handle complex magnet layouts, offer stray‑field immunity, and support fieldbuses and serial interfaces suitable for precision servo control.

Sensor manufacturers such as Allegro and Monolithic Power highlight the advantages of magnetic sensing in difficult environments. Hall‑effect devices, Tunneling Magneto Resistance sensors, and multi‑axis magnetic ICs provide non‑contact feedback with long life and resistance to contaminants that defeat optical encoders. For harsh industrial robotics, that is often the practical path to maintaining nanometer‑level control over years of operation rather than weeks in the lab.

The key with feedback is matching the sensor architecture to the mechanical layout and the control strategy. A high‑end rotary encoder on the motor shaft may give sub‑microinch synthetic resolution, but if backlash and flex in a long mechanical chain separate the motor from the load, your product will never see those numbers.

Actuators And Mechanics

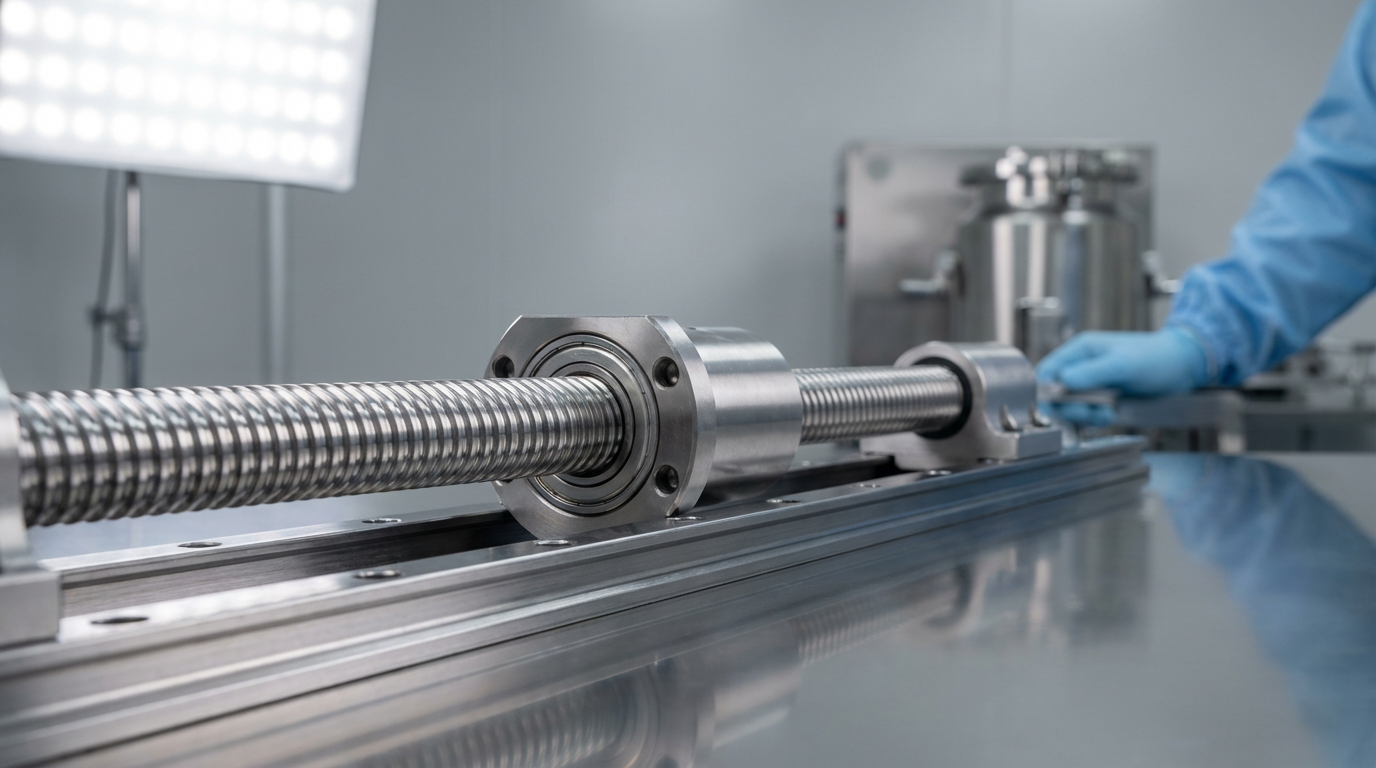

No position module can overcome poor mechanics. Industry briefs on precision motion control stress that precision is a function of mechanical design, feedback, electronics, and environment together. Bearings, guides, ball screws, belts, couplings, and structures all introduce straightness errors, friction, stiction, and compliance.

Linear actuators, as summarized in industrial automation articles, convert motor rotation into linear motion via lead or ball screws and can reach micron‑class accuracy with high repeatability. For nanometer‑level positioning you are often relying on precision ground ball screws, linear motors, or flexure‑based mechanics, but the same principles apply. The screw or guide must be straight and stiff, the support structure must not twist under load, and the layout must minimize parasitic motion.

In hydraulic systems, the challenge is even greater. W.E.ST. Elektronik’s positioning controllers use high‑resolution SSI sensors with micrometer‑scale resolution for hydraulic cylinders, combined with dynamic control algorithms tuned for zero‑lapped valves. These modules compensate static positioning errors and manage synchronization between axes, but again, the underlying valves, cylinders, and frames have to support that precision.

The practical takeaway is simple. If you want nanometer‑grade performance at the load, you design mechanics, actuators, and mounting with that in mind from day one. You do not bolt a “nanometer” encoder onto a flexible frame and expect miracles.

Control Architecture And Algorithms

On the control side, nanometer modules are essentially very refined position‑control systems.

Motion‑control primers, such as those from the Association for Advancing Automation, explain that a motion system is built from mechanisms, motors, drives, controllers, HMIs, and feedback sensors. The controller serves as the brain, the drive and motor as the muscle, the network as the nervous system, and the mechanical stage as the skeleton. Control modes include position, velocity, and torque, implemented in open‑loop or closed‑loop topologies.

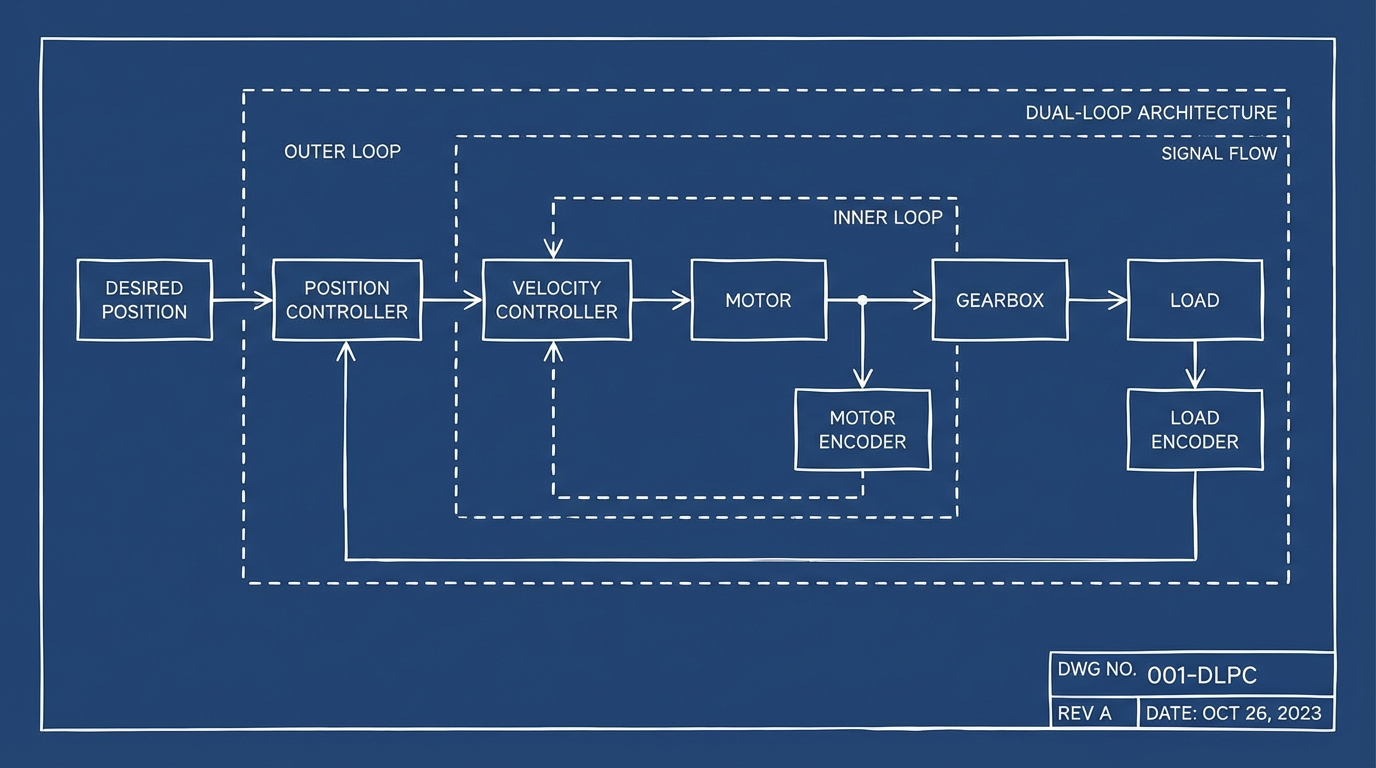

For nanometer work, closed‑loop is non‑negotiable and usually layered. A standard architecture uses an inner current loop in the drive, a velocity loop around the motor, and an outer position loop around the load. Rotational position‑control tutorials describe PID control in practical terms: the proportional term tackles instantaneous error, the integral term eliminates long‑term offset, and the derivative term damps out rapid changes. Feedforward terms improve tracking when you know the system dynamics and expected disturbances.

Research on soft‑robotics control, such as fractional‑order PID (FOPID) applied to assistive robots like the I‑SUPPORT platform, shows how more advanced controllers can improve robustness and accuracy when dynamics are highly nonlinear. Those methods use additional tuning parameters and kinematic decoupling to enhance precision and computation efficiency. In heavy industry, we usually stay with well‑understood PID‑style controllers for maintainability, but the principle is the same: you tune the loop to minimize error without exciting resonances or noise.

High‑end precision motion controllers, like those covered by SAE Media Group, layer sophisticated trajectory planning on top of these loops. They synchronize multiple axes over high‑performance buses, run algorithms for vibration suppression, and provide programming languages that integrate motion with process steps. That ecosystem is where nanometer‑grade position control modules live.

Dual-Loop Position Control: When One Encoder Is Not Enough

One recurring theme in nanometer projects is that a single feedback loop is often insufficient.

Advanced Motion Controls explains dual‑loop position control as the use of two feedback devices, one on the motor and one on the load. Mechanical elements—gears, ball screws, belts—introduce friction, flex, and backlash, so the motor shaft position diverges from the load position when loads vary.

A single encoder on the motor lets the drive regulate motor position and velocity very well. However, if a long ball screw bends under cutting forces or a belt stretches, the actual load position may be off by amounts that are huge compared with your nanometer target.

Putting the only encoder on the load improves final positional accuracy but can destabilize the system. Backlash can briefly unload the motor, causing sudden accelerations as the controller chases a load encoder that is not moving the way the motor expects.

The dual‑loop approach solves this by closing an inner velocity loop around the motor using its encoder and an outer position loop around the load using the load encoder. The position loop generates velocity commands proportional to position error and feeds them to the velocity loop. In this way the system maintains stable motor behavior while correcting for mechanical slop and compliance at the load.

For modules that claim nanometer resolution, dual‑loop or similar architectures are often the difference between hitting advertised specs at the motor shaft versus at the workpiece. In my integration work, any time there is a significant mechanical chain between motor and process point—long screws, belts, gearboxes—I treat dual feedback as a serious requirement, not an optional upgrade.

Magnetic And Absolute Sensing In Nanometer Modules

Nanometer‑ready modules lean heavily on modern magnetic and absolute sensors.

Educational material on absolute position sensors in robotics points out why: absolute sensors report a unique position value within their range at all times. That eliminates homing strokes and reduces the need for complex calibration routines after power‑up. In exoskeletons, industrial arms, or mobile robots, these sensors allow the control system to react safely and precisely even after interruptions.

Magnetic sensor vendors outline a spectrum of technologies that position modules can exploit. At one end are Hall‑effect switches and latches used as solid‑state limit switches, commutation sensors, or simple odometers. They replace mechanical switches with contactless devices that are robust, consistent, and tolerant of temperature variations.

Moving up the ladder, linear Hall sensors and 3D magnetic sensors provide analog or digital outputs proportional to magnetic field components. Allegro’s documentation describes how 3D sensors can measure multi‑axis motion for factory automation mechanisms, while specialized 2D angle sensors are optimized for high‑speed motor position sensing and servo control.

At the high end, advanced magnetoresistive and TMR encoders, as highlighted by Monolithic Power and Arrow, provide very fine angle resolution, low latency, and strong immunity to stray fields. Devices like Melexis multi‑die encoders use vernier magnet rings and dual Triaxis ICs to compute absolute angle, speed, and turn count, and are explicitly targeted at robotic joints and industrial motors.

Taken together, this sensor stack allows position modules to measure motion with granularity that matches or exceeds nanometer‑class mechanical capability, while maintaining robustness in the face of dust, oil, and vibration.

A concise way to think about sensor choices in a nanometer‑grade module is summarized below.

| Sensor family | Strengths for nanometer modules | Typical role in the system |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute encoders | Always know position; no homing; support safety and recovery | Primary position feedback on critical axes |

| Magnetic encoders | Non‑contact; robust to contamination; high resolution | Motor or load feedback where optics are impractical |

| Hall switches/latches | Simple, rugged on/off and commutation sensing | Limits, homing references, basic motor commutation |

| 3D magnetic sensors | Multi‑axis field measurement; compact | Joysticks, complex linkages, compact robotic joints |

When evaluating a position control module, you want clarity on which of these sensor technologies it supports directly and which require external hardware.

Precision Motion Control In Real Systems

System-Level Factors That Make Or Break Nanometer Accuracy

Automate’s deep dive into precision motion control makes one thing clear: precision is not a property of any single component. Achievable accuracy and repeatability are shaped by mechanical design, feedback quality, drives and electronics, controller algorithms, and sensor data integrity.

Mechanical contributions include flatness and straightness of motion, bearing tolerances, backlash, and wear over time. Electrical aspects include servo loop bandwidth, processing power, and noise characteristics of the drive and controller. Environmental influences include temperature swings, floor vibrations, and electromagnetic interference.

Common error sources listed in the industry brief will sound familiar to anyone who has commissioned a high‑precision axis: electromagnetic noise from nearby drives, machining errors in actuators, permanent‑magnet motor cogging, dynamically changing loads in robots, and signal integrity issues from long or poorly shielded cables.

When you are trying to realize nanometer‑level control, each of those error sources matters more than it does in a general automation cell. The same is true for configuration and programming. Motion‑control fundamentals emphasize correct motor sizing, actuator selection, and control‑loop tuning as integrated decisions, not isolated line items.

In practical terms, a nanometer‑grade position module should be part of a stack that has been thought through as a whole: motors, actuators, couplings, encoders, fieldbuses, cabling, and algorithms selected and matched with precision in mind.

Trajectories, Throughput, And Process Quality

Position control at this level is not only about hitting a target; it is about doing so repeatably, quickly, and without damaging the part or the machine.

Precision motion‑control articles distinguish between accuracy, repeatability, minimum incremental motion, and in‑position stability. For many processes, repeatability and stability matter more than headline resolution. A system that can return to the same position within a small, known band and hold that position under load is far more useful than a system that can theoretically command a one‑nanometer step but wanders randomly while holding.

Higher precision usually enables higher throughput because machines can run faster without sacrificing tolerance. Examples cited include optical systems, advanced microscopy, and DNA sequencing platforms where multi‑axis nano‑positioning allows high‑speed scanning while preserving alignment. In semiconductor and photonics applications, automatic alignment, test, and assembly require stages that can scan, locate optimal coupling points, and return to them within tens of nanometers.

A nanometer‑capable position module must therefore support not only fine step sizes but also sophisticated trajectory planning and motion blending. Industry sources note that high‑end precision controllers often support motion definitions using G‑code or custom scripting languages instead of only ladder logic, plus faster I/O processing and integrated process control constructs. These capabilities make it practical to choreograph complex multi‑axis motions that still comply with mechanical limits and process constraints.

Diagnostics And Predictive Maintenance

One of the quieter benefits of modern position modules is diagnostics and predictive maintenance.

Boston Engineering emphasizes predictive maintenance as a strategic benefit of advanced motion control. By analyzing motion data, systems can predict wear, schedule maintenance proactively, reduce downtime, and improve overall equipment effectiveness.

Digital valve positioners from suppliers such as Siemens and Kimray show how this concept looks in process control. These devices combine precise valve positioning with onboard diagnostics, performance monitoring, and maintenance alerts, accessible over digital communication protocols. They are effectively position control modules for process valves, designed to be remotely monitored and tuned.

In nanometer‑grade positioning, similar ideas apply. High‑end modules typically provide detailed fault codes, trend data for errors and drive currents, and tools for auto‑tuning and commissioning. W.E.ST. controllers, for instance, add automatic commissioning assistants that detect sensor scaling, valve deadbands, maximum speeds, and optimal control parameters. This reduces commissioning effort and helps maintain performance over time.

From a systems integrator’s point of view, these diagnostic features are not optional extras when you are operating at nanometer scales. They are how you keep a finely tuned system within spec over years of thermal cycles, part changes, and mechanical wear.

Pros And Cons Of Pushing To Nanometer Resolution

It is tempting to assume that more precision is always better, but nanometer‑grade modules involve real trade‑offs.

On the positive side, higher precision directly improves process capability in industries where tolerances are shrinking. Semiconductors, photonics, advanced medical devices, and certain defense systems already depend on sub‑micron and nanometer‑scale motion. Precision motion enables tighter tolerances, improved yield, and shorter cycle times at those tolerances. Once you have reliable positioning at that scale, you often discover new process windows and product designs.

Another benefit is flexibility. Boston Engineering notes that advanced motion control makes robotic systems more adaptable, allowing things like rapid model changeovers in automotive lines. Nanometer‑capable modules generally come with rich motion languages, higher‑bandwidth control, and better synchronization features, which you can exploit even if your current process does not need extreme precision.

However, the downsides are significant. Cost is the obvious one: nanometer‑grade sensors, mechanics, and controllers command a premium, and the engineering time to design, tune, and verify them is substantial. Complexity is another. A general‑purpose PLC module using simple position instructions is much easier for an average plant technician to understand than a multi‑axis precision controller with dual‑loop feedback and custom scripting.

There is also the risk of over‑engineering. If your process tolerance is comfortably in the micron range, a nanometer module might add cost and fragility without measurable benefit. Precision motion control experts recommend starting from process requirements. If customers complain that your system is “close but not where it needs to be,” you are hitting accuracy limits. If they say “nobody makes a system that works every time,” repeatability is the issue. Only when you see those symptoms relative to state‑of‑the‑art tolerances and throughput targets does it make sense to reach for nanometer‑class technology.

The final trade‑off is sensitivity to environment. A module capable of nanometer resolution will faithfully measure and react to nanometer‑scale disturbances: floor vibrations, thermal drift, and electrical noise. In a robustly engineered facility, that is manageable. In a typical industrial shop with uneven floors, temperature swings, and heavy equipment nearby, you may spend more on mitigation than the performance gain justifies.

How To Specify And Evaluate A Nanometer-Grade Position Module

Evaluating these modules is not fundamentally different from choosing any motion platform, but the stakes are higher and the margins smaller.

The first step is to quantify what you actually need in terms of accuracy and repeatability at the workpiece, not at the motor shaft. Industry discussions of precision motion make clear distinctions between resolution, accuracy, and repeatability. Resolution is the smallest commanded step your module can represent. Accuracy is how close the actual position is to the commanded position. Repeatability is how tightly repeated moves cluster. For real processes, accuracy and repeatability at the load dominate.

Once you have target numbers, you can work backwards. On the mechanical side, decide whether your architecture is fundamentally capable of reaching those targets. For example, a long, belt‑driven axis supported on basic bearings is unlikely to ever deliver nanometer‑level accuracy at the load, no matter how capable the control module is.

On the control side, examine the module’s feedback options. Ask whether it supports both motor‑mounted and load‑mounted encoders and whether dual‑loop control is part of the standard feature set. Review the supported encoder types: absolute or incremental, magnetic or optical, SSI, SPI, or analog interfaces. Compare that list with the sensor technologies described by suppliers like Melexis, Allegro, and Monolithic Power and see how easily you can integrate the sensors your application needs.

Software and integration capabilities matter as much as raw control performance. SAE Media Group’s coverage of precision motion controllers describes platforms that offer modern IDEs, scripting languages, and G‑code support, making it easier for engineers with general programming backgrounds to work with precision motion. Consider whether your team will be comfortable with the toolchain, or whether you will depend on a few specialists.

At the system level, look at how the module integrates with your existing automation environment. Motion‑control basics emphasize the role of networking standards like EtherCAT and the importance of compatibility with PLC programming models such as IEC 61131‑3 and PLCopen motion libraries. A module that communicates cleanly with your PLCs, safety systems, and data collection infrastructure will be far less painful to deploy than one that demands a parallel world of software.

Finally, pay close attention to diagnostics, commissioning tools, and vendor support. As examples, W.E.ST. controllers include commissioning assistants; Maple Systems publishes demo projects that show PLC‑HMI‑motor integration; Aerotech invests in an entire software ecosystem around its Automation1 platform. Those are the kinds of tangible support structures that make nanometer‑grade modules usable outside of research labs.

Lessons From The Integration Trenches

From a veteran integrator’s perspective, a few patterns show up repeatedly when teams first move into nanometer‑class positioning.

One pattern is overconfidence in datasheet numbers. It is common to see designs that assume the encoder resolution quoted by a sensor vendor translates directly into system accuracy. When you probe with a metrology‑grade reference—often a measurement system with roughly an order of magnitude better precision than the device under test, as metrology experts recommend—you discover that mechanical errors, thermal drift, and servo tuning dominate.

Another pattern is underestimating the impact of cables, grounding, and noise. Motion‑control articles list electromagnetic interference and poor wiring as major contributors to error. In practice, that means nanometer‑scale modules demand disciplined cable routing, shielding, bonding, and power distribution. Treating sensor lines with the same rigor as RF signals is not a luxury; it is a requirement.

A third pattern is neglecting long‑term behavior. Many systems pass initial acceptance but drift out of spec after months of operation because bearings wear, lubricants change, or environmental conditions were not fully characterized. This is where the predictive‑maintenance capabilities emphasized by Boston Engineering and the diagnostics built into modern positioners and axis controllers become essential. Logging position errors, drive currents, and temperature over time allows you to see degradation early and act before customers notice.

In short, nanometer‑level modules are achievable, but only when you treat them as part of an engineered ecosystem and give equal attention to mechanics, sensing, control, and operations.

FAQ

What is the real difference between nanometer resolution and nanometer accuracy?

Resolution is the smallest command increment your position module can represent, often derived from encoder counts and interpolation. Accuracy is how close the actual load position comes to the commanded value. A module may support nanometer‑scale resolution while the overall system delivers only much coarser accuracy because of mechanics, noise, or poor tuning. When qualifying equipment, always ask for accuracy and repeatability figures at the load, not just resolution numbers at the motor.

Do I really need a dedicated precision motion controller, or can a PLC module handle nanometer tasks?

For many applications that only need fine positioning occasionally or over short travels, a capable PLC with a well‑designed motion module, like the Maple Systems position control approach, can be sufficient. However, once you require synchronized multi‑axis motion at high speed, advanced trajectory planning, or sustained nanometer‑scale accuracy, dedicated precision motion controllers like those described by SAE Media Group become much more practical. They are engineered specifically for high‑bandwidth servo control, complex trajectories, and rich diagnostics.

How can I tell if my environment can support nanometer-level performance?

Start by assessing vibration, temperature stability, and electromagnetic noise where the machine will live. If the floor is subject to frequent impacts or heavy traffic, if ambient temperature swings substantially over a shift, or if high‑power drives and welders are nearby without good segregation, you will need mitigation: isolation platforms, environmental control, and careful electrical design. Industry guidance on precision motion emphasizes considering these environmental factors early in design, because no position control module, however capable, can fully compensate for an unstable foundation.

Closing Thoughts

Nanometer‑grade position control modules are no longer exotic, but they are still unforgiving. When you pair appropriate mechanics, robust sensing, sound control architecture, and disciplined engineering, these modules can turn demanding specifications into reliable production realities. Approach them with clear requirements, realistic expectations, and a willingness to treat motion control as a system‑level discipline, and they become an asset instead of a science experiment.

References

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12383376/

- https://in.ewu.edu/financialservices/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2024/11/Position-Control-11.19.24.pdf

- https://www.automate.org/motion-control/industry-insights/developing-precision-motion-control-systems

- https://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/mechanismsrobotics/article/13/6/061004/1100432/A-Low-Cost-Highly-Customizable-Solution-for

- https://blog.boston-engineering.com/precision-in-motion-the-power-of-advanced-motion-control-and-automation-in-robotics

- https://www.a-m-c.com/what-is-dual-loop-position-control-and-where-is-it-needed/

- https://www.industrialprofile.com/the-power-of-precision-unveiling-the-remarkable-benefits-of-linear-actuators/

- https://kimray.com/training/how-pneumatic-analog-electro-pneumatic-and-digital-control-valve-positioners-work

- https://maplesystems.com/position-control-with-maple-systems-plcs/?srsltid=AfmBOoocU9IS05O3JFt1I3Higpz66Bndu89d0l35fUv_lqk5ronBxGsK

- https://www.onlinerobotics.com/news-blog/understanding-basics-rotation-position-control

Keep your system in play!

Related Products

Related articles Browse All

-

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu...

amikong NewsSchneider Electric HMIGTO5310: A Powerful Touchscreen Panel for Industrial Automation2025-08-11 16:24:25Overview of the Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 The Schneider Electric HMIGTO5310 is a high-performance Magelis GTO touchscreen panel designed for industrial automation and infrastructure applications. With a 10.4" TFT LCD display and 640 x 480 VGA resolution, this HMI delivers crisp, clear visu... -

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ...

BlogImplementing Vision Systems for Industrial Robots: Enhancing Precision and Automation2025-08-12 11:26:54Industrial robots gain powerful new abilities through vision systems. These systems give robots the sense of sight, so they can understand and react to what is around them. So, robots can perform complex tasks with greater accuracy and flexibility. Automation in manufacturing reaches a new level of ... -

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

BlogOptimizing PM Schedules Data-Driven Approaches to Preventative Maintenance2025-08-21 18:08:33Moving away from fixed maintenance schedules is a significant operational shift. Companies now use data to guide their maintenance efforts. This change leads to greater efficiency and equipment reliability. The goal is to perform the right task at the right time, based on real information, not just ...

Need an automation or control part quickly?

- Q&A

- Policies How to order Part status information Shipping Method Return Policy Warranty Policy Payment Terms

- Asset Recovery

- We Buy Your Equipment. Industry Cases Amikong News Technical Resources

- ADDRESS

-

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

32D UNITS,GUOMAO BUILDING,NO 388 HUBIN SOUTH ROAD,SIMING DISTRICT,XIAMEN

Copyright Notice © 2004-2026 amikong.com All rights reserved

Disclaimer: We are not an authorized distributor or distributor of the product manufacturer of this website, The product may have older date codes or be an older series than that available direct from the factory or authorized dealers. Because our company is not an authorized distributor of this product, the Original Manufacturer’s warranty does not apply.While many DCS PLC products will have firmware already installed, Our company makes no representation as to whether a DSC PLC product will or will not have firmware and, if it does have firmware, whether the firmware is the revision level that you need for your application. Our company also makes no representations as to your ability or right to download or otherwise obtain firmware for the product from our company, its distributors, or any other source. Our company also makes no representations as to your right to install any such firmware on the product. Our company will not obtain or supply firmware on your behalf. It is your obligation to comply with the terms of any End-User License Agreement or similar document related to obtaining or installing firmware.

Cookies

Individual privacy preferences

We use cookies and similar technologies on our website and process your personal data (e.g. IP address), for example, to personalize content and ads, to integrate media from third-party providers or to analyze traffic on our website. Data processing may also happen as a result of cookies being set. We share this data with third parties that we name in the privacy settings.

The data processing may take place with your consent or on the basis of a legitimate interest, which you can object to in the privacy settings. You have the right not to consent and to change or revoke your consent at a later time. This revocation takes effect immediately but does not affect data already processed. For more information on the use of your data, please visit our privacy policy.

Below you will find an overview of all services used by this website. You can view detailed information about each service and agree to them individually or exercise your right to object.

You are under 14 years old? Then you cannot consent to optional services. Ask your parents or legal guardians to agree to these services with you.

-

Google Tag Manager

-

Functional cookies

Leave Your Comment